RANDOMNESS, ON WHOSE TERMS?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FORMAL SHOOTS BY WORK BY PHOTOGRAPHERS, both in studio and on location, walk a strange tightrope, hybridizing the feeling of having captured “real life” in mid-step alongside the craft of making it look just a little better than real. We accept, for example, that the portrait shooter, with his bounce lights and backdrops, renders a more balanced or idealized version of us than truly exists in nature. In fact, we count on it, making comments like “make me look good!” during the process.

So deeply entrenched is this sense of formal, commercialized composition that, in our own work, we can’t help but see after-images of all that photographic salesmanship, no matter how bold or visionary we believe our stuff to be. I’ve now been around long enough to see re-runs of themes or techniques from many other sources creeping into my own, whether or not I’m trying to do a tribute or homage. My mind just has such a vast file of visual reference points from films, magazines, or culturally key moments that hints of at least some of them can’t help bleeding into my own, “original” pictures.

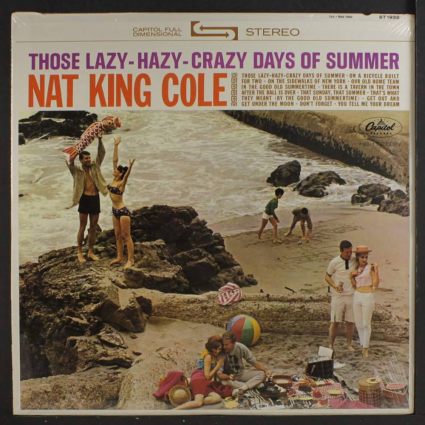

Often this happens without my recognizing it, at least at the instant I’m making an image, as the influence of an earlier photo informs something that I assume I’m creating wholly out of the moment. The seemingly random snap you see up top, of fun-seekers on the coastline of La Jolla, California is both of the moment and an echo of moments past, back whenever I first formed a mental diagram of what “a day at the ocean” should look like. Three weeks after I shot it, a snatch of an old Nat King Cole song brought up the memory of the album cover that was used to market that tune. The staging of that studio shoot’s “caught in the moment” ambience makes even a “candid” shot go through some sort of filter in my head. The gestures should look like this; the bodies should be arranged thus; The frame should be here.

In photography, there is no such thing as a “good” or “bad” influence, only influence itself. We make believe that we are stopping time inside a box in a way that is truly random, but it is actually experience which decides on which terms that randomness is applied.

Leave a comment