OFF THE SHELF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

JERRY SEINFELD ONCE REMARKED. OF GUYS OBSESSED WITH OVERUSE OF THE REMOTE CLICKER, that they “aren’t interested in what’s on tv; they’re interested in what else is on tv.” Funny and true, and also indicative of some photographers, in that, while we love what our basic gear does, we’re really excited at the prospect of hybridizing equipment from any and all sources. We’re interested in what else our cameras can do.

My 1977 Minolta 50mm, dormant in my closet for over twenty years, now fronting my Nikon mirrorless.

Many of us at least stray slightly from the only-original-manufacturers mindset (that is, only Canon lenses for my Canon camera, etc.), yielding to some degree of lens bi-curiosity, leading us to adapt glass from other makers to find the perfect marriage between body and optic. It’s not always a win for our work, but the journey is far more fun than the destination anyway. And the old hybridizing romance of the DSLR period has easily found a contemporary equivalent with the move to mirrorless cameras, as dozens of third-party equipment houses have rushed modestly-priced adapters to market for converting older glass, including many manual-only lenses, to use on mirrorless platforms. Photographers tend to be tinkerers; they are fascinated by what happens when you do this to this. And now it’s easier than ever to get answers for that tantalizing question.

Like many reading this, I spent my DSLR years adapting old manual primes from the film era, treating myself to optics with all-metal construction, smoother aperture and focus adjustment, superior sharpness, and a huge cost savings. These tended, for the most part, to be Nikkor lenses for my Nikon cameras, and so no adapter was required, since I was going from an F-mount lens to an F-mount body. Then, after making the leap to mirrorless, I adapted the same lenses to continue their use on a Z-body (using so-called “dumb” adapters that don’t communicate with the camera body, another cost-savings for someone who’s shooting without the need for AF). And finally, I’m enjoying going completely off-brand to give new life to optics that have been gathering dust since my first days behind a viewfinder.

Moonstone Beach near Cambria California, 9/6/25, seen through the eye of a 1977 Minolta 50mm prime.

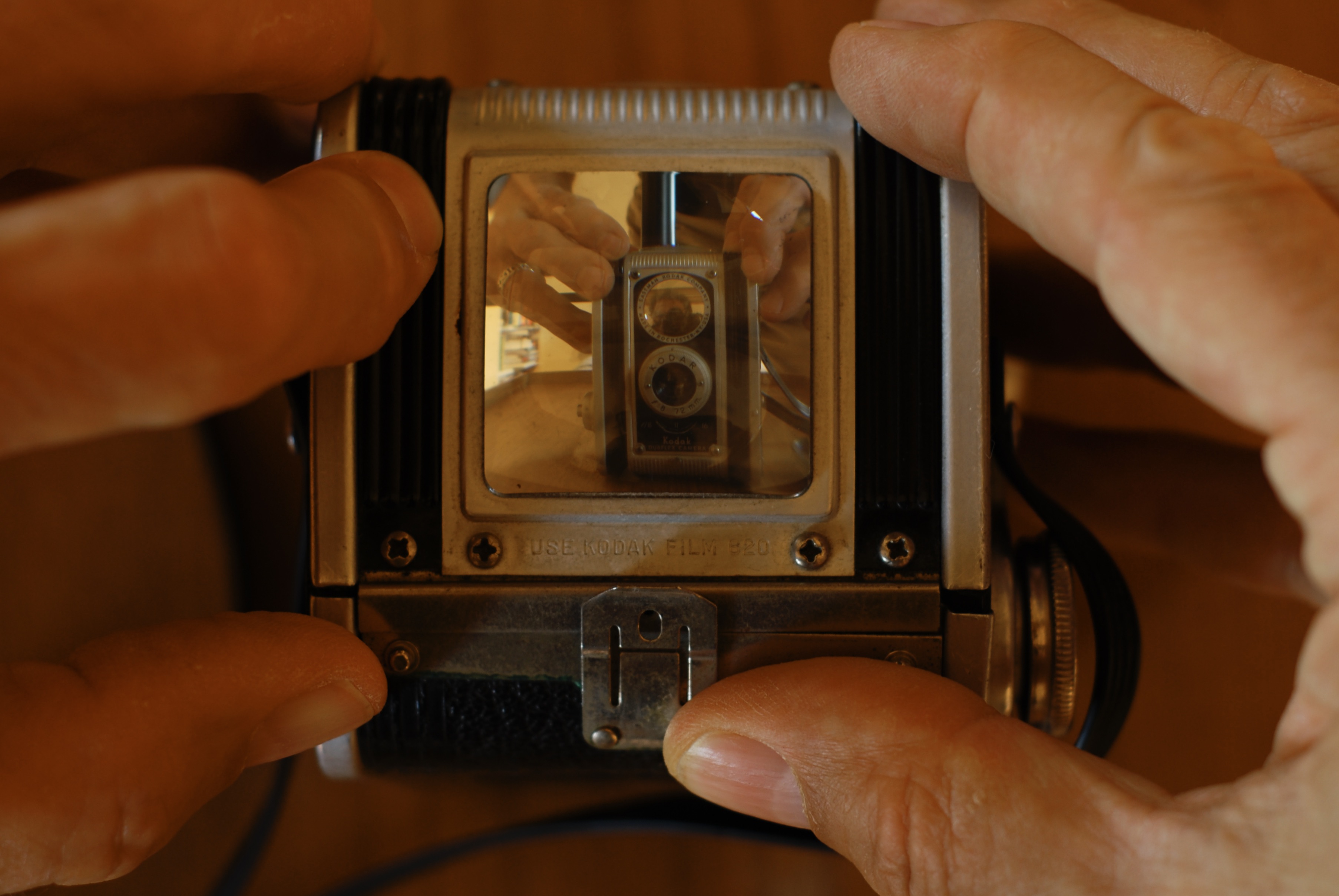

The lens shown here came from a Minolta SRT200, a ’70’s-era SLR that I grabbed for $100 in the ’90’s when my daughter decided to enroll in a high school camera class. The class came and went, but I kept the camera, fitted out with a Rokkor-X MD 50mm f/1.7 prime lens. I spent a lot of time, just before and just after 2000, shooting mostly slide film with it, sticking it in the closet only after the purchase of my first digital point-and-shoot. Learning that, decades later, it could be restored to service as a sharp and clear prime for the mere cost of a $30 adapter put a huge grin on my face, and, at this writing, we have been renewing our old love affair for several weeks. Scores of articles are now online as to the efficacy of this or that bit of “legacy” glass on mirrorless bodies, most written with a flavor of delight, or adventure, or both. Some even claim that such vintage optics perform even better on digital cameras than they ever could on film. Your mileage may vary. As for me, I’m just beginning to explore what else is on my camera.

Oh, and hand me that clicker, willya?

TECH’d IN THE HEAD

Curiouser and curiouser: welcome to the camera format wars, final rendition.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU WANT TO SIMULATE THE EXPERIENCE OF LEAPING OUT OF A PLANE WITHOUT A CHUTE, then get into the business of predicting trends in photography. The boneyard of critical writing is crammed with the carcasses of wizard wannabes who boldly pronounced what the Next Big Thing in camera tech was going to be. Still, even given that caveat, there are some big tectonic shifts in Camera Land that even a dullard like me can see coming.

Smart people call these shifts “inflection points”. These are the folks who get great grades on term papers. Me, I just say, “hey, is this anything?” Whatever your wording, we seem to be at such a place as of this writing , which is early 2022.

Little more than a decade after the introduction of the first mirrorless cameras, prognosticators great and small now seem uniformly confident in predicting that this is the year that DSLRs go on life support and the family calls in the priest. Recently, no less a cadre than the venerable PetaPixel predicted that both Canon and Nikon would end their commitment to DSLR development and model introduction in 2022. And, suddenly, they are far from alone. The argument goes that, just as SLRs were a forward leap in convenience and performance over rangefinder cameras, so mirrorless does what DSLRs do more accurately and far easier. Normally such forecasts would be largely a matter of opinion, but something new has been added.

That “something” is the fact that more manufacturers than ever are closing the DSLR product line on both ends, both discontinuing older models with no comparable successor and in bringing fewer new models, especially entry-level-priced models, to the market for the first time. And then there is the raw science, which says that, minus the bulky box-and-mirror part of DSLR’s viewing apparatus, lenses in mirrorless cameras can be placed extremely close to the focal plane, affecting sharpness, low-light performance, chromatic aberrations, and, yes, the total curb weight of the unit. This also means that your older DSLR lenses, with adaptation, might well work better on a mirrorless body. Other factors in this sea change include people like myself who are going to mirrorless in order to upgrade to full-frame for the first time, and figure they might as well go with a format that manufacturers are now throwing their full weight behind.

You and I both know several “I’ll never” people who will stick with their chosen format until the last dog is hung, and mazel tov to them. Shoot what you want, love what you shoot, etc. However, when the makers of a particular tech are cutting back on new models of it, even going so far as to reduce choices and support with the existing models in that format, including their best sellers, it might be time, as they say in Hollywood, to strike the set.