BOTH SIDES, NOW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

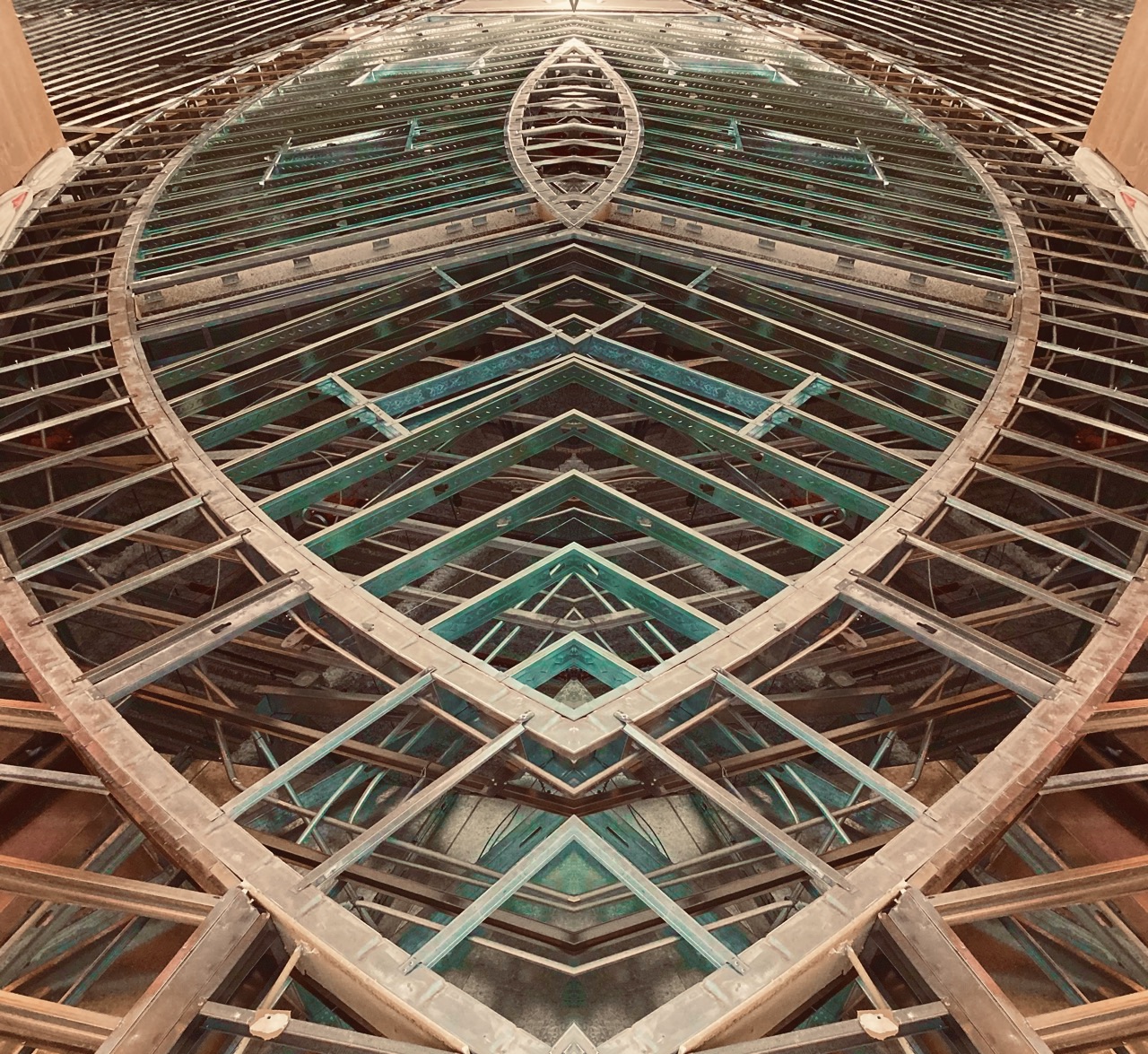

THOSE OF US WITH ROOTS IN THE STONE AGE may recall the opening of the old Disney TV series Wonderful World Of Color, which consisted of a burstingly brilliant kaleidoscope, endlessly unfolding behind the show’s title card. It was a stunning way to display the infinite rainbow of hues of the early color network broadcast, echoing what everyone had seen when turning those little cardboard tubes filled with rattling bits of color glass; the hypnotic appeal of the symmetrical.

From ancient architectural frameworks to medieval tapestries to the intricately balanced frameworks of common spaces in the present day, we love to imitate the visual counter-balances seen in nature, such as the patterns within a flower, or the delicate web of design in a snowflake. And, as photographers, especially in an age in which anything can be manipulated or faked to our heart’s content, we are often seduced by the temptation to artificially impose that balance on our images, to make the world uniform and orderly. Why is this visual urge so strong?

A genuine fake. Because reality is, you know, just reality…

Psychologists claim that humans take a kind of comfort from “balance”, feeling more rooted, in, for example, inside a church that has four matching wings conjoined by a central hub, or a wagon wheel, or a plaza built around a square mosaic. There are even studies that indicate that we think of symmetrical faces in other people as more attractive than non-symmetrical ones. Small wonder, then, that we deliberately simulate symmetry where none naturally exists. As in our younger days, when we first folded sheets of paper into fourths, then cut pieces out of them that, once unfurled, replicated the cuts four times in perfect opposition to each other, we use photographs not only as proof of natural balances, but as a jumping-off point toward the creation of Other Worlds, better ones with a neater, more mathematical precision. We play Creator, or at least Re-Creator.

Which to a say, in roundabout fashion (my usual method), that photographs are only marginally documentary in nature. They evolve from ideas that may or may not reflect the actual world. That’s why they aspire to art.

Leave a comment