EX POST FACTO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHING THE BUILDINGS THAT ONCE COMPRISED THE VISUAL LANDSCAPE of a vanished time is always an entire “term paper” project for me. Finding antique structures that were designed for very specific uses, and trying to shoot them in as close to their original form as possible, always trips me into reams of research on how they survived their eras, what threatens their further survival, or what grand new uses await them in the future. And most of those stories begin with my quite accidentally strolling past them en route to somewhere else.

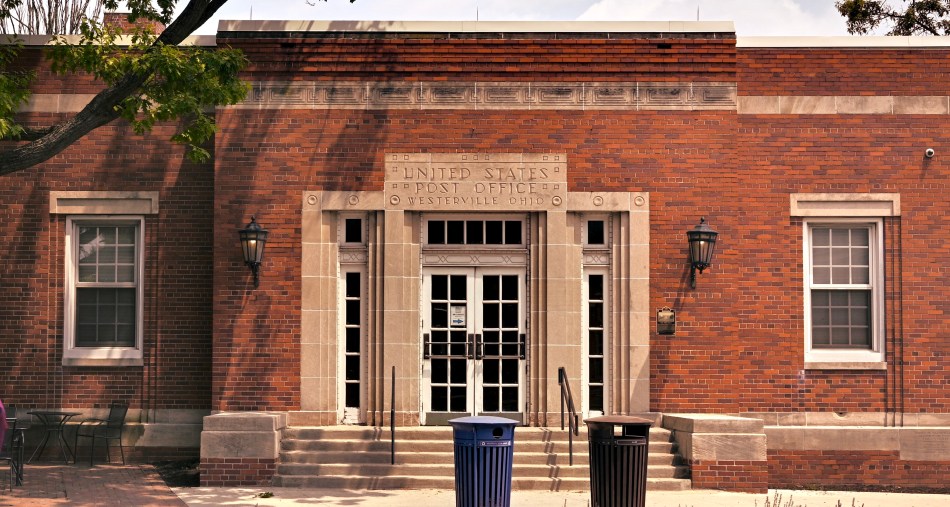

This post office from 1935 popped into view as Marian and I were taking a recent post-lunch stroll around the reborn town of Westerville, Ohio. Photos from its grand opening show it to be nearly identical in appearance to the first day of its service, decades before its namesake was even officially a city. It was one of dozens, perhaps hundreds of village post offices built during the Great Depression by the job-creating New Deal program known as the W.P.A., or Works Progress Administration. Most of the P.O.s erected in those austere years were, themselves, no-frills affairs, devoid of all but the simplest decorative detail and as structurally logical as a Vulcan with a slide rule. Straight, clean lines. Modest appointments. Simple tablatures over the entrance.

The Westerville P.O.’s most distinct feature was actually inside the building, where a “noble work of the common man” mural typical of the period (another federal make-work project to help sustain starving artists) once decorated one wall. Sadly, Olive Nuhfer’s “The Daily Mail” depicted a neighborhood that resembled the artists’ native Pittsburgh, a bone of contention for the Westerville locals who pronounced it out-of-step with the small-town ethos of the area. In time, the painting was removed and returned to a permanent place in the Steel City.

Photographing these kinds of buildings is an exercise in restraint, in that I seek to idealize the structure, to lift it back up out of the past if you life, but without over-processing or embellishing it. Seeing it as close to how it first was is enough for me; it is absolutely of its time, and, as such, it’s a gift.

Post Script (see what I did there?): It’s also encouraging that a regional restaurant chain will soon give the empty building new life as a brew pub. However, it’s more than a little ironic in a town that was once the national headquarters of the Anti-Saloon League, the bunch that forced Prohibition down America’s throat (without a chaser), meaning that Westerville was, for a time, the busiest small postal system in the country, simply by virtue of sending out millions of pieces of anti-hootch literature every year. John Barleycorn gets the last laugh.

MAGICAL (PHOTOGRAPHIC) THINKING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

HOLLYWOOD LOVES STILL CAMERAS, exploiting them for dramatic impact in thousands of films over the first one hundred years of the movies. Entire plots hinge on the ability of protagonists, from intrepid reporters to dogged private eyes, to save the day or solve the mystery with a judicious snap, images that spring up in the eleventh-hour of a murder case or point to the tough truths in a medical inquiry. Seems Our Hero (or Heroine) is always on hand with some photographic device that ties the story together and brings it in for a successful landing, ofttimes making his/her camera a key player in the story. Magical thinking regarding photography is a part of the collective movie myth.

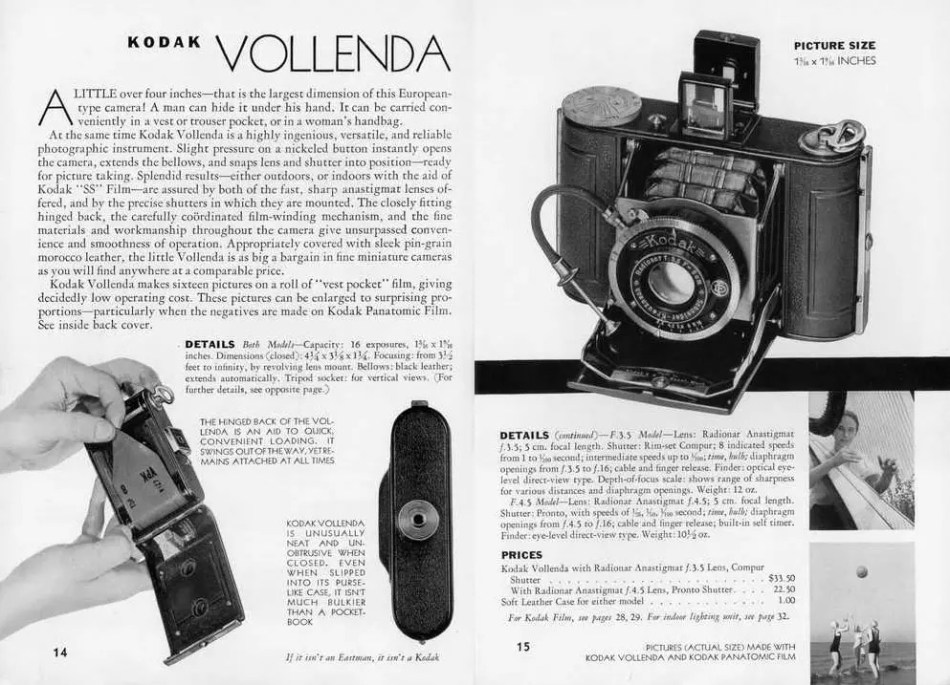

HBO’s recent (and successful) re-boot of the old Perry Mason series is the latest case of a camera becoming a key agent of action in a teleplay, spawning scads of on-line theories about the make, model and performing properties of the sleuth/attorney’s chosen kit. The candidate with the most votes so far looks to be the Kodak Vollenda, a compact folding model (see original ad, above) created by German optical wunderkind and former Zeiss employee August Nagel in 1929 and marketed in the U.S. after he entered into a co-operative deal with Kodak in 1931, the year before the Mason stories are set. The early versions of the camera produced images of roughly 1.25 x 1.62 inches, each taking up half a frame on 127 roll film, giving the shooter better bang for his film buck in terms of picture count but also limiting the size of its negatives, and, in turn, how sharp enlargements (for those climactic courtroom scenes) could be. For your average superstar lawyer shooting a lot of medium and long shots in natural light (or even darkness) with a maximum aperture of f/3/5, this could spell trouble, at least if you were counting on the results for critical evidence. Hooray for Hollywood.

The Vollenda in Perry Mason’s era would probably have fed on the old Verichrome Pan film, with a not-too-aggressive ASA (or ISO) of 125…again, pretty good in brightly lit situations, but not so great when skulking around dark alleys or spying on suspects misbehaving across nightlit streets. But, ah, well, the thing looks amazing in actor Matthew Rhys’ hands, and is historically consistent with the period, despite the fact that its original $33.50 list price would equate to well over $600 in today’s currency, a bit steep for a down-on-his-luck gumshoe in the middle of the Great Depression. But, ah, well, as Billy Shakes often said, the play’s the thing, and Hollywood’s greatest photographic illusion is in selling us all the fantasy of a super camera that save the day by the end of the final fadeout.

Cut.

Print it.

ECHOES OF HOPE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN DARKNESS LOOMS IN THE HEART OF MAN, THE SIZE OF ANY LIGHT IN THE ROOM IS LARGELY IRRELEVANT. What matters is that someone, anyone, struck a match. The light puts physical limits on the dark. The light points toward escape. The light is the promise of continuation, of survival.

During the present forced hibernation among nations, it’s easy to compare today’s responses to The Latest Troubles with the responses seen in other crises. Everyone is free to make those comparisons, to crowd the air with arguments about who did what, and, once all the discussion abates, having a record of what we’ve tried and learned over the years is the work of art. Art records the dimension of our dislocations, measures the distance between Old and New Normals. Memorials, built by survivors, exist to delineate what happened to us, and, more importantly, what happened next.

There are four open-air “rooms” in the FDR Memorial in Washington, D.C., each designed to symbolize one of the separate presidential terms of Franklin Roosevelt, along with references to the specific challenges of those four eras-within-an-era. One such room houses sculptural reminders of how the average person interacted with the White House as it faced the singular challenges of the Great Depression. The figures, by George Segal (1924-2000), are spare, gaunt, haunting. One tableau shows an emaciated farming couple standing with grim determination amidst reminders of the Dust Bowl. Another shows a string of ragged men waiting in line for bread. My favorite figure shows a seated man leaning forward on his knees, his eyes fixed on the small “cathedral” radio set located just inches away. The sculpture is more than a mere tribute to Roosevelt’s encouraging series of “fireside chat” broadcasts, which acted to bolster the frightened nation as banks failed and privation swept across America like a plague of locusts. It is a snapshot of the relationship between leaders and the led. A bond. A lifeline of trust.

For Segal, who himself spent some of his college years scratching out a living on a chicken farm, and whose personal loss was measured in the Holocaust-related deaths of much of his family, the figures were emotional measures of the space taken up by mere mortals in alternating renderings of both pain and potential, expressed in a bold blend of materials. Covering models’ bodies completely in orthopedic bandages, he removed the hardened shells of plaster and gauze from their human “bearers” to create life-sized hollow spaces in three dimensions, leaving the details of the bandages in full view. In addition to his impactful pieces at the FDR Memorial, his surviving work in this format includes memorials to the gay liberation movement and the victims of Kent State.

Where do we regular shooters come into it? Making photographs of other people’s art from other types of media can range from mere snapshots to a kind of re-interpretation. The eye of the beholder shapes the eye of the camera. In Segal’s work for the FDR, a time so far removed from our own is transported back to anguished relevance. Generations later, we are all still seeking that bond, that link between leader and led. If we achieve it, the souvenirs of earlier days are merely quaint. If we can’t find that connection, however, these Echoes Of Hopes Past become more harrowing in their haunting power.

Because we need to walk toward the light.

Anyone have a match?