IT’S NOT THE SHOES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

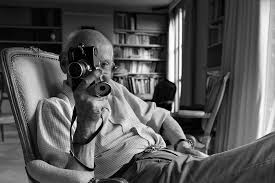

I WAS RECENTLY READING AN ARTICLE that centered not so much on the unique talent of legendary photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson as on the succession of early 35mm Leica’s that were his go-to tools. In the writer’s defense, I believe he was at least trying to make the case that HCB’s kit merely facilitated his own wonderful vision, assisting but not making his greatest images. However, a reader that already regards certain cameras with the zeal of a cult worshiper could easily come away with the opposite view, that those Leicas were, themselves, a determinative force in how his pictures came out. And that’s unfortunate.

People who sell consumer goods tap into the human habit of crediting things for what might be achieved by intelligent use of those things. Eat this breakfast cereal and break the four-minute mile. Ride around your neighborhood on the tires that won the Indy 500. The pitch even works in reverse psychology, as in Spike Lee’s brilliant ’80’s ads for Nike, in which he kept asking various basketball superstars, “it’s the shoes, isn’t it?” The payoff was, of course, a knowing wink to the consumer, i.e., “well, no, it’s not really the shoes, hee hee, but, P.S., Jordan wears ’em, so…” And, for shooters, the equivalent pitch: buy this camera/lens/attachment/app and become a great photographer. It’s an easy approach for advertisers, because it appeals to our own bias about what creates excellence, which, in many cases, the advertisers have “taught” us to believe in the first place.

Cartier-Bresson, whose sense of composition was said to be so keen that he was known to merely raise the camera to his eye and click in one unbroken motion, developed that economical sense of execution on his own, irrespective of what gear he was using. He employed the simplest, most streamlined approach to making pictures that he could, and, as a matter of historic accident, the early Leica’s, themselves very no-frills affairs, gave him all the machine he needed to get the job done, and nothing more. Other manufacturers could likely have served the same elemental function for him, but, as fate would have it, Leica got there first, and so became an inextricable part of his legend, a lazy kind of “oh, that’s how he did it” explanation for a genius that simply cannot be explained.

One wonders how long the camera industry could thrive if manufacturers could not (a) make us discontented with what we already have, and (b) convince us that the next toy we buy will make us a Cartier-Bresson. But the real “camera” in photography is the one positioned behind our eyes. Knowing where to hit the nail-head is more important than merely buying a premium hammer. It really, honestly, swear to God, is not the shoes.

THE WONDER OF THE WALKABOUT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM ASTOUNDED BY PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO UNERRINGLY APPREHEND the essentials of the ideal framing for a composition. And, believe me, they are out there; artists whose eye immediately fixes on the ideal way to launch a narrative in a static shot. The legendary Henri Cartier-Bresson was one. He reputedly kept his camera hanging around his chest until the very instant he was ready to make a shot, whereupon he lifted his Leica to his eye, and snap, one flawlessly framed image after another. The photo editor’s dreaded wax pencil never defaced his images in search of crop lines or a way to trim away fat to make HCB’s pictures communicate more effectively. There was no “fat”. The editor was already looking upon perfection.

For me, composition is more typically trial and error, and so my favorite subjects are things that will more or less remain in place long enough for me to literally walk around them in search of their “good side”. or the angle that best serves the visual story I’m after. Street photography offers up some opportunities for such focused study, but, in that real-time environment, the stories are often morphing too quickly, and one has to trust to instinct to nail that one second of eloquence, since a follow-up or re-take may not present itself. But, when I can, I try to be slow, deliberate. To do things with purpose and on purpose.

Digital, and the luxury of nearly endless numbers of exposures with immediate feedback, has been a life saver for me in a way that film, God bless its little analog heart, never was. This instantaneous concept-to-result cycle has saved many an image for me, since I am granted the ability to make a lot of wrong pictures very quickly, thus arriving at the right picture with more efficiency. The gentleman seen here in two frames was very accommodating in ignoring me, allowing me to squeeze off perhaps fifteen shots as I walked from his rear left side to his rear right side. Along the way, the scenery and props rose and fell as focal points, subtly changing the message of the photographs. Were I expert enough to follow Cartier-Bresson’s example, the image just just above might have been my goal, but, as I dwell among mere mortals in Photo-Land, I find myself by getting lost a bit. I go on walkabout.

CHANNELING THE MIGHTY “MISC”

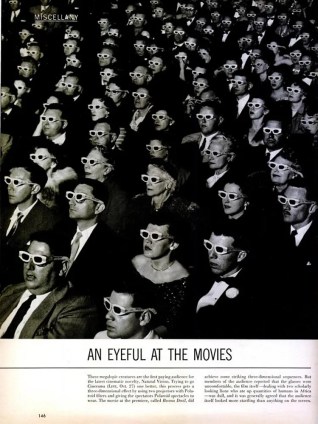

A famous snap at a 1950’s 3-d movie audience from Life magazine’s popular “Miscellany” page.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I GET THESE MOMENTS.

If I were the talent of a Henri Cartier-Bresson, the protean street photographer, I might call these brief flashes of humanity/absurdity, and the the pictures they produce “The Decisive Moment”, HCB’s phrase for the perfect collision of factors snatched from the timeline at precisely the correct instant to make something magical. As it is, at my level, such moments are more like “things that make you go ‘hmmm'”. Same aim, vastly different results.

As I have mentioned before in these pages, in my youth, the weekly arrival of the new Life magazine at the house was something of an event. Many illustrated news digests, in that golden age of periodical publication, tried to hit the perfect balance between essential current events coverage and “man in the street” photo essays, but Life, for my money, remains the standard. My favorite feature over the years was always found on the final page, just inside the back cover, a one-more-for-the-road picture called “Miscellany”. The photos in it were apropos of nothing beyond themselves. They weren’t connected to a hard-news story or editorial content. They were merely bits of whimsy, most of the “can you believe this happened/can you believe we shot this?” variety. Fun stuff.

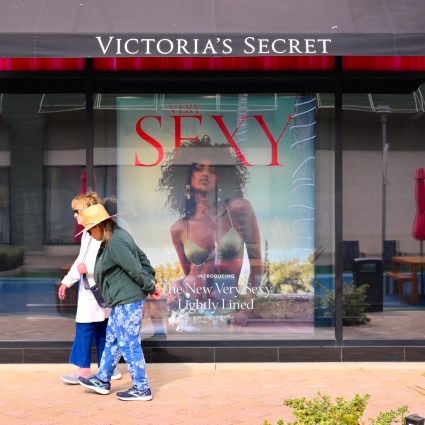

You Talkin’ To Me??, February 2024

I still feel those images in my bones during street work. Bizarre juxtapositions of the beautiful and profane; strange meet-ups between the serious and absurd. In the case seen here of the two mature ladies walking past a recruitment poster for some kind of foundation fantasy, I saw these ladies approaching from just outside my right periphery while I was composing what would have been merely a shot of the shop window. As they walked closer I realized that they were going to cross in front of it, and, just like that, my brain clicked in Miscellany mode. How could I not bring the two factors together. It was ridiculous. It was fun. Click.

Photographs can often act as comedy relief, or at least a safety valve, against the buildup of pressure from issues that hang on us far too heavily. Sometimes you just have to step back and smile. Or remind others too. Channeling the mighty “misc” is one way of getting there.

LINING UP THE STARS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE CREATION OF A PHOTOGRAPH IS, AT ONCE, A VERY SIMPLE ACT and one of the most complex of creative processes. It is both instinctual and intellectual, a thing of sudden inspiration and a constant weighing of variables. It is, simultaneously, a marveling at the random arrangement of all the stars in heaven, and an attempt to line them up in a pattern of one’s own desire. Few photographers have been able to consistently balance these disparate aims over the course of a career. Fewer still have been able to reduce the process to written wisdom as well, a quality which makes Henri Cartier-Bresson a prophet among poets. He not only defined human truth with his beloved Leica (which he called “the extension of my eye”) but also managed to speak about that miracle in a manner no less articulate than his grandiloquent images.

HCB’s career coincided with the rise of the great photographic feature magazines of the 20th century, like Life, Look, Parade, and Harper’s Bazaar, where a new kind of reportage was being invented on a daily basis, with photographs evolving from mere illustrations of mega-events to stories about people who lived their lives beyond the obvious ranks of fame and power. Photographers were entering into a more emphatically emotional role, both harvesting and inserting interpretive energy into what had formerly been a simple act of recording. Global displacements of individual humans, measured between the World Wars in the Great Depression and other seismic events generated image makers who could train their cameras to take the measure of joy and suffering in an incredibly intimate fashion. Cartier-Bresson’s beat, which was global as well, enhanced his eye for the universal, the common feelings that crossed cultural and geographical boundaries. But he was also helping to create a new way of seeing, a system that was equal parts brain and heart.

In describing what he would later call “the decisive moment”, that golden instant where subject and story reached their peak of impact, HCB described what, to him, was the aim of the enterprise:

For me, photography is to place head, heart, and eye along the same line of sight. It’s a way of life. (It is) the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event, as well as of a precise organization of forms.

Composition. Interpretation. Empathy. Narrative clarity. These became the mainstay elements of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s work, the difference between just freezing something in a box and capturing something of fleeting but essential value. They also became the pillars of a discipline that would eventually be labeled “street photography”. Perhaps it was his practiced way of seeing which, late in life, led him back to painting, the visual medium for total control. It is one thing to learn to see, and it is something else entirely to be able to harness that vision, to make the camera execute it with a minimum of loss from the original conception. But the anticipation that something is about to happen keeps us addicted, and that in turn keeps us trying. As HCB himself recalled of the moments before the click, “I’m a bag of nerves waiting for ‘the moment’…and it wells up and up and it explodes…it’s a physical joy, dance, time and space all combined. Seeing is everything.” It is a testament to how perfectly Henri pre-conceived a composition that almost all of his photographs are exactly as he shot them, without cropping or re-framing of any kind. They were just that right…..the first time.

We all occasionally get seduced by equipment, techniques, fads, even windy essays like this one, veering from the central mission of our art. But that mission is as simple as it is elusive: seeing is everything. With it, you can light a candle against the darkness.

Without it, you are worse than blind: you are unknowing.

GRAND BALLET

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOMETIMES THROWING EVERYTHING INTO THE POT MAKES FOR BETTER STEW. Yeah, of course a simple bowl of tomato soup can be elegant, understated. But so can pitching every stray ingredient into the mix and hoping the carrots play nice with the asparagus. Matter of taste depending on one’s mood.

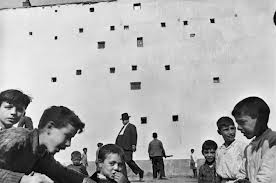

Henri Cartier-Bresson placed his camera at the intersection of “now” and “next”.

So it goes with street photography. Some insist that isolating a single story, a singular face, a tightly framed little drama is the way to go. And that is certainly true much of the time. But so can casting a wide net, framing a grand, interactive ballet of conflicting lives and destinations. It’s like the concentrated, two-man drama of Waiting For Godot versus the teeming crowd scenes of The Ten Commandments. Both vibes come from the street. Just depends on what story we’re telling today.

From the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the great street photog of the mid-20th century, I learned to love the seeming randomness of crowds and their competing destinies. HCB was a genius at showing that something wonderful was about to happen, and I love to see him capturing the moment before there even is a moment. His still images fairly beg to be set into motion: you are dying to see how this all comes out. If HCB is new to your eye, I beg you, seek him out. His work is a revelation, a quiet classroom of seeing sense.

I have posted both quiet stories and big loud parades to these pages. Both have their appeal, and both demand a discipline and a selective eye, which means I have a few light years’ worth of learning before me in both areas. That’s the great thing about art. You can’t get done. You can be on the way, but you will not get there. Not if you’re honest with yourself.

For the viewer, myself included, you have to go beyond “snap looking” which is the audience’s equivalent of “snapshooting”. Some images require that you linger, just as some wines are to be sipped instead of guzzled. Slowing down when viewing a frame is the best tribute to whatever pauses the photographer took in creating it in the first place. This picture business is truly a shared project between creator and user.

Gosh, I feel all brotherly and warm-hearted today.

Sort of an urge to be part of the crowd.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Henri Cartier-Bresson (estone6.wordpress.com)

- The decisive moment (photovide.com)