Dream Machines

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AT THIS WRITING, I HAVE JUST COMPLETED A LONG WEEKEND characterized by three really early morning treks to three consecutive birdwatching sites, a brutal trifecta of trudging and toil that has left me footsore and bent over, worn raw from bad shoes and the nagging shoulder weight of a five-pound telephoto. The weather, as is often the case along the Pacific coast, was iffy, which meant that the percentage of keeper shots plunged even further below my usually sorry harvest. It will take me another three days to sift through the raw takings, alternatively cursing the blown opportunities and over-celebrating the luck-outs. And so, as an antidote to that very long march, I have plunged into the only pure fun I gleaned during the entire ordeal.

Spoiler alert: it’s not a picture of a bird.

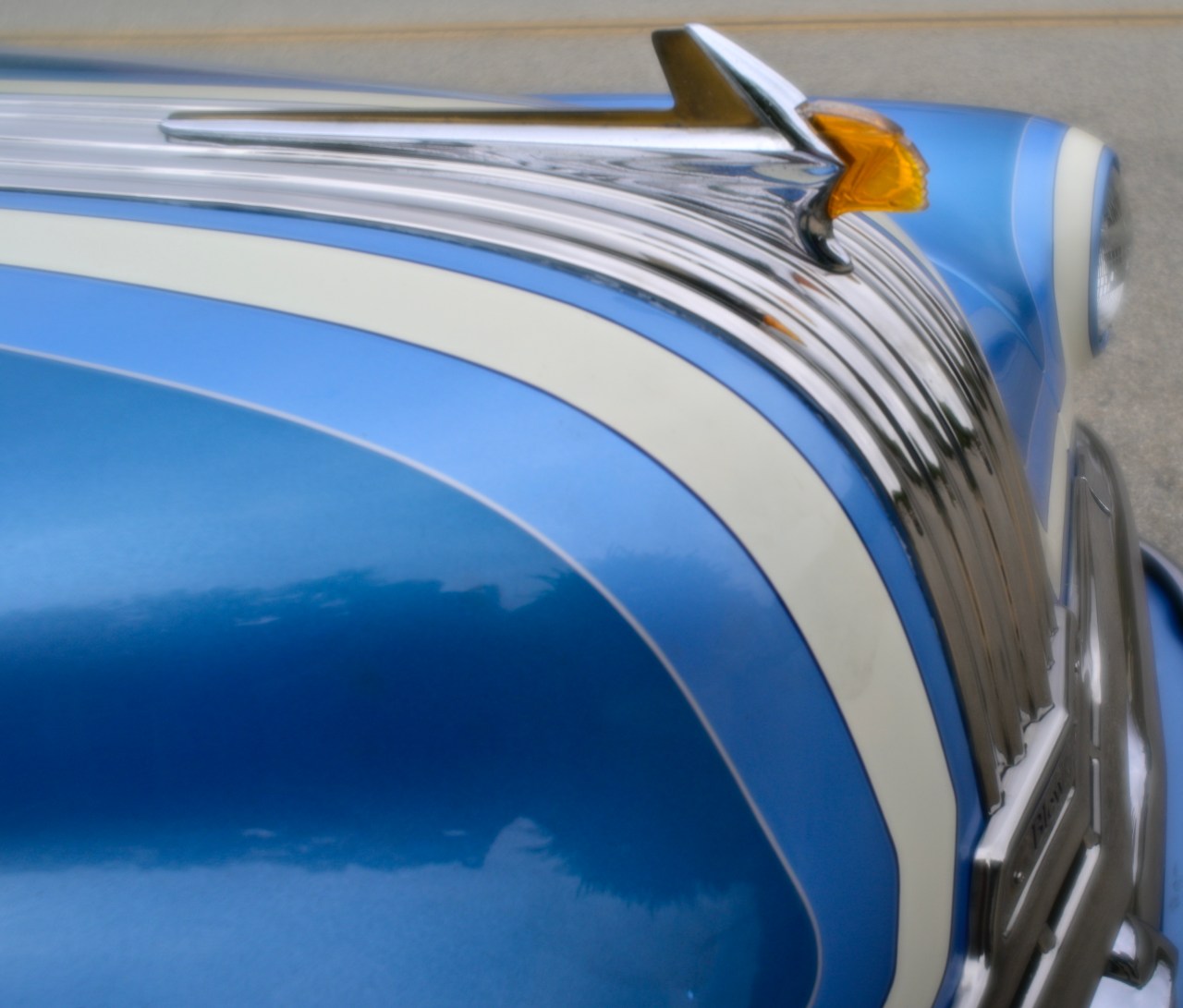

Well, in its day, it certainly soared like one. And, for me, limping several blocks from my apartment to visually make love to a supreme achievement in pure, seductive design, as an emotional balm for my aching’ dogs, it definitely made my heart take wing. I don’t know where this vintage 1940’s Pontiac Torpedo came from. The home where it was parked is, regularly, home to owners of elegant machines from bygone eras, usually of the pimp-my-ride-low-rider variety. One thing I do know is that none of these dream machines hang around for more than a few days. That made it Pilgrimage Time for me and my Lensbaby Velvet 28, which, shot nearly wide open, wraps its subjects in a dreamy haze that encases the focused image without blurring it. Watch the over-exposure on the chrome highlights, buy yourself some insurance with the use of focus peaking, and, voila, an express ticket to Hotrod Heaven.

I feel a little better equipped now to wade through three days’ worth of “maybe” images of birds while my knees and shoulder mend. I needed a quick dose of control, or at least the illusion of being able to make a picture instead of hoping I captured one. The fever’s broken now. But oh, what a delightful delirium!

UM, THANKS, I GUESS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO ARE EVEN MINIMALLY HONEST WITH THEMSELVES learn early on how to own their mistakes, to admit that sadly, such-and-such a picture just did not work out. Even if they are slow in learning this, they will no doubt be forced to answer the question “what happened here?” from other photographers. This acts as a double-strength multiplier for humility. Good photos speak softly in praise of their creators. Bad photos wear loud colors and walk around with a bulls-eye on their behinds.

The one chance a shooter has to pass off a poor shot is if the result, however comprised in his own estimation, actually manages to “speak” to someone else. All it takes to break us out of a sell-pitying sulk is for someone, anyone to ask, “oh, how did you do that?”, allowing us to glibly remark along the lines of “oh, you see what I was up to, did you?” or “yes, that’s what I was going for all along..” In such cases, it’s forgivable to just take the win, rather than answer the viewer with “are you nuts? This pictures stinks!”

Sunrise Over Bard Lake, Simi Valley, near Thousand Oak, California, 2/3/25

I recently had positive reaction to such a shot, a picture that I had already rejected as close, but no cigar, a landscape that you see here. It was the result of an early dawn enveloped in bright hazy glare combined with a superzoom, needed for the bird walk I was starting, but which, due to its tiny sensor, was guaranteed to render details mushier the farther in I cranked on my subject. And so you see a very soft, muted rendering of all the tones, resolving into a look that photogs have come to term “painterly”, which is French for “not as sharp as I’d hoped for”. Still, several people had given me oohs and aahs on it, so it was very tough to tell them they didn’t know what they were talking about. The scene is, after all, very dreamy, and might still have been on the mushy side even with a more sophisticated camera. The aggravating thing for me is when a picture works for everybody else but me. Makes me wonder how many art museums are brimful of works their creators regard as flawed. I’m sure the math on such a study would be surprising.

In the meantime, thanks, I reply, adding, as a post script, you oughta see what happens when I actually know what I’m doing. The P.S., of course, is silent. And it damned well is going to stay that way.

SOFT AROUND THE MEMORIES

I originally thought a soft, glow-y look would “sell” the vintage look of this truck. Not so sure now…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M A BIG BELIEVER IN SECOND DRAFTS. Part of this comes from my work in commercial copywriting, a field that has only two truths: (A) the customer is always right, and (B) the customer will almost never accept your first effort without changes. Another part of my comfort with re-do’s is my background as an illustrator, a craft that teaches you that your vision seldom comes straight out of the pencil in its fullest or final form. Both professions thrive on negative feedback, and being cool with that can reduce the number of heartaches you’ll face in other imperfect endeavors, such as being a photographer.

Factors like time, travel and opportunity can certainly force shooters to accept their first attempt at an image, simply because getting on a flight or meeting someone for lunch or dodging the rain can mean they have no choice but to accept the one try they’re going to get on a given subject. But even within a narrow time span, digital gear makes it much easier for for us to shoot-and-check-and-shoot-again quickly, resulting in more saves and keepers. But these are all technical considerations, which still ignore the biggest, and most crucial factor in getting the picture right. And that’s us.

Take Two, several days (and several degrees of sharpness) later….

Sometimes we leave a shoot satisfied that we nailed it, only to find, back home, that we were nowhere near the nail and didn’t know how to use the hammer. We didn’t choose the right glass, or the right angle, or, most importantly, the right conception of what would make the image speak. If we’re lucky, we are geographically close enough to the original site that we can go back for a retry. And if we’re really lucky, the time span between first and second draft has shown us what needs to change.

In the two shots of a rusted truck seen here, I was certain, at first, that merely suggesting the wear and tear on the old wreck with a hazy, soft look, would sell a certain nostalgic mood, whereas, once I returned home, my masterpiece just looked like a mess. There’s a red line between soft focus and mush, and I had truly stumbled across it. Fortunately, I was close enough to the truck to drive back and try again with a conventionally sharp image, which I think actually works better overall, at least for me. Fortunately, the time between my first and follow-up attempts was enough to let my approach evolve, and, luckily, I wasn’t blocked from giving it a second go because of time, travel or opportunity. Point is, there is sometimes real value in being forced to wait, to delay the instant gratification that our tech tells us should be our default. Sometimes, we come closer to the mark when we are forced to hurry up and wait.