VISIONS FROM OTHER KINDS OF EYES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT TOOK ME OVER HALF A LIFETIME OF STUDYING WHAT I CONSIDERED THE “GREATS” OF WORLD PHOTOGRAPHY to realize just how biased my own eye was, how it was inclined to see all cultures mostly as my own culture was inclined to see. The first images I loved were basically travelogues, that is, scenes from so-called “foreign” nations, as interpreted almost exclusively by Western photographers. “My” people, looking at “their” worlds, traveling afar and coming back to me with stories whose truth I took at face value.

It has taken me a long time, too long, to seek out the visions of people my cultural prejudices regarded as “the other”, to delight myself in the storytelling of indigenous people reporting and commenting on their own worlds, instead of waiting for outsiders (us) to tell those stories for them. It has led me to amazing work, and, lately, to a remarkable Chinese artist named Fan Ho, a visionary whose career spanned over seventy years, ending in 2016, and standing as a true chronicle on the evolution of China since the close of WWII. He was a street photographer long before such a term existed, developing an instinct for what Westerners called “the decisive moment” that elusive instant when all the narrative powers of an image are in perfect sync.

Born in Shanghai in 1931, Ho began snapping at an early age with a Kodak Brownie box camera, graduating to a Rolleiflex K4A, the camera that would be his career-long tool, when he was just fourteen. Developing his film in the family bathtub, Ho was almost completely self-taught, insisting that equipment and technique both took a back seat to emotion, and that he “didn’t work with any sense of purpose”. “I’ve always believed that any work of art should stem from genuine feelings and understandings”, he told an interviewer in 2014. “As an artist, I was only looking to express myself. I did it to share my feelings with the audience. I need to be touched emotionally to come up with meaningful works.”

By 1949, Ho’s family moved to Hong Kong, then beginning its rocket-sled ride into the fraternity of super cities, and experiencing unique growing pains and turmoil as it did so. Ho’s mastery of contrasting tones and shadows made for some of the most impactful black-and-white photography of the twentieth century, a magical balancing act between revealing and concealing. Beginning in 1956, his entry into exhibitions earned him over 280 international awards for excellence, and by the 1950’s, he segued into his second career in cinema, becoming a director a few years after and producing feature films until around 1980. Re-locating to San Jose, California in retirement, and encouraged by friends to return to still photography, he instead chose to curate his old negatives to gain access to shows in the United States, where many critics discovered the breadth and range of his output. At this writing, the easiest way to see even part of his work is in online image searches, as nearly all of his formally published collections are either out of print or seriously expensive…when they can be found.

I am one of many who wound up being late to the Fan Ho party, but a party’s still a party no matter when you arrive, and I am grateful for the chance to learn still another way to see, regardless of where the lesson originates. After all, the only real chance you have to learn anything is to admit how little you know.

KICKED OUT OF THE NEST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“YOU MUST SUFFER TO BE BEAUTIFUL“, runs the old adage, which I always took to mean that anything worthwhile comes with some degree of sacrifice. Without musing too much about what happens to all of us who suffer and still are ugly, let’s at least admit that, like it or not, beauty, or art, has to be coaxed and groomed into existence, which I suppose is why the noun artist is so frequently preceded by the modifier tortured. The take-home of this, at least for me as a photographer, is that no real growth or improvement comes unless you risk frustration and/or failure. There’s a reason why many mommy birds teach their kids to fly by simply kicking them out of the nest. Comfort is the enemy of creative evolution.

That’s why this entry seems to cry out for an ornithological illustration, as I myself have found the pursuit of bird images to be the perfect vehicle for kicking myself out of my own creative nest. Other than landscape work, I find that shooting birds requires greater amounts of patience and humility than anything else I’ve ever undertaken in photography. Even with sixty-plus years of experience under my belt, making bird pictures puts me immediately back at Square One, feeling like an ignorant child who doesn’t even grasp which way to point the bloody camera. In terms of applying what I’ve learned over a lifetime in pursuit of greater success with my feathered friends, I keep thinking of the old Firesign Theatre comedy album, Everything You Know Is Wrong, and I fantasize that, had I the temperament of a Buddhist monk, I might, somehow, have gotten better than I am at the whole game.

The image seen here is typical of thousands of bird images that I’ve attempted that fall into some murky grey zone between Almost Good and Bloody Embarrassing. You’ve also taken pictures like this, with one or two elements showing promise and others that seem to say Sorry, I’m New At This. “Suffering to be beautiful”, in the case of my wildlife shots, means taking what’s an average “hit ratio” of decent-to-failed pictures and learning to be satisfied with less. A lot less. Turns out that living creatures who must spend all day, every day, just trying to stay fed and alive are remarkably unconcerned with whether or not I get the shot. Go figure. That means that my photographs are made at their whim, not mine.

I have to think of myself, therefore, as a witness to a great picture rather than as its author. The number of things under my control in a standard shooting situation shrinks to near invisibility for bird work, and so, whenever I get lazy or stale, I really ought to “sentence” myself to a bird shoot just to be forced to work at the highest level of intentionality and mental focus. Returning to our opening meditation on birds leaving the nest, it’s worth remembering that some youngsters who fledge from precarious perches, like a spiny Saguaro cactus for example, have one try at flinging themselves clear of the plant to avoid being impaled on it. Now that’s someone who understands something about leaving your comfort zone.

RISE OF THE UPSTARTS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Pancake with a punch: newcomer Viltrox’. body-cap-sized 28mm f/4.5 for full-frame cameras (various mounts) with AF.

THE MARKET FOR CAMERA LENSES HAS ALWAYS EXPANDED in all directions at once, affording photographers an embarrassment of riches when it comes to selecting their best optical options.

There is always the most traditional route, in which various makes of cameras promote their own proprietary lines of brand-new products from macro to telephoto and everything in between…what one might call the “brand-loyal” route, a path which can lead to a substantial investment in cutting-edge tech. Then there is the “lest we forget” wing, in which new cameras are paired with older model optics long vanished from their parent company’s active product line, often adapted from one format to another, such as the refit from DSLR-era glass to new uses on full-frame cameras. Lately, there has also been a kind of retro retrenchment, as lo-fi (but not always lo-cost, lol) lenses are marketed to “serious shooters” for a rebirth of randomness, error or “authenticity”, as unpredictability is re-introduced to a process that’s grown, for some, a bit sterile.

And now, as we near the one-third mark on the 21st century, a tremendous wave of fresh product is coming from a new crop of third-party optics houses entering the market at the low end of the investment scale, providing amazing features that traditionally were found only in costlier major-brand lenses. Established third-party players like Tamron and Sigma have been joined by new players that include Laowa, Rokinon, TTArtisan, 7Artisan, and Viltrox, with more players entering the game each year. And while the new kids had mostly been sporting models with manual focus only, that barrier is falling as well. The small-as-a-body-cap Viltrox 28mm f/4.5 pancake lens shown here delivers quick, responsive auto-focus for just $99, with other brands rushing their own wafer-thin, fixed-focal-length versions to market as we speak. Reviewers whose critical default is a down-the-nose dismissiveness toward upstarts have had to rethink their biases, and the “rules” of who can be competitive in the optical field are likewise being radically rethunk. Long gone are the days when one country, tradition or brand had a lock on what constituted a “good” lens, a leveling of the playing field which can only benefit the consumer.

IT COULD ONLY EVER BE THUS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

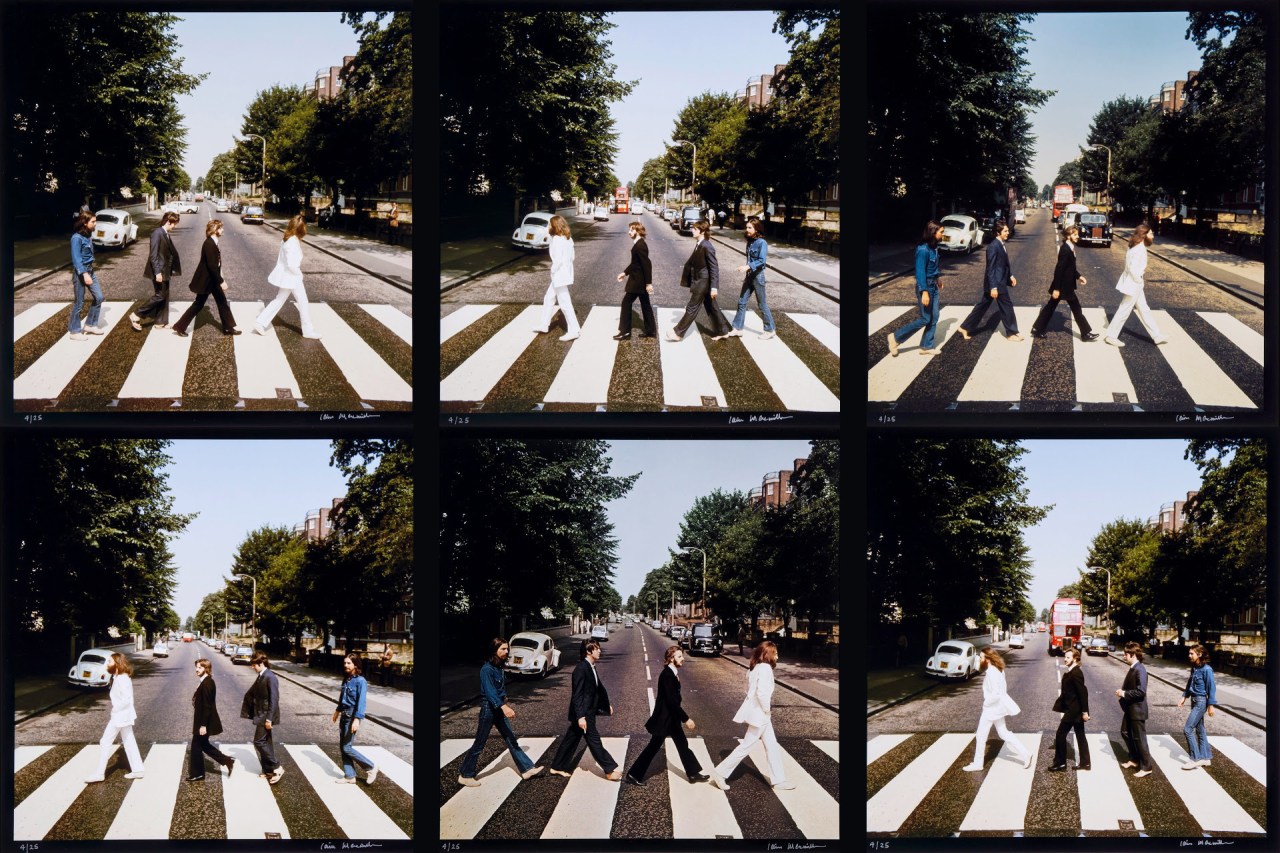

COMPARED TO THE INTRICATE ASSEMBLY OF THE COVER SHOT FOR THE SGT. PEPPER ALBUM just two years prior, the creation of the cover for 1969’s Abbey Road, the Beatles’ final studio album, was a relative snap (excuse the expression).

Whereas Pepper’s “people we like” montage of life-sized celebrity cut-outs took days of prop arrangement and a true jigsaw process of addition and subtraction, the task for photographer Iain Macmillan on Abbey was relatively simple. Find a suitable location, engage a cop to briefly block traffic, and parade the Fab Four back and forth in what would become the most iconic procession in pop music history. Macmillan, a friend of both John Lennon and Yoko One, arrived at the site with a rough idea of the object of the shoot, as Paul McCartney had already worked up some pencil sketches of how the group wanted to be arranged in the “zebra” crosswalk. Iain needed only to clear the intersection and climb a borrowed ladder to get the correct angle and framing for all four Beatles.

And since I can hear you all asking out there in the blogosphere, Macmillan’s weapon of choice for the assignment was a Hasselblad fronted by a 50mm lens. He shot at f/22 and 1/500th second, given that it was a clear August day with plenty of sunlight to spare. The entire shoot totaled no more than six frames, with McCartney selecting the fifth shot in the sequence, reportedly because it showed the group walking away from the Abbey Road studios, a kind of subtle farewell to the site of their best work over the previous decade. It also came closest, among the frames, to give the impression that they were all in the same general step rhythm (make of that what you will). What the final choice shows most clearly, though, given the global familiarity of the final product, is the way in which a simple editorial call can take a shot that’s merely one in a generally similar batch of images, and make it not only acceptable but inevitable, as if to say, of course, that’s the only one which would have worked.

In examining the options that might have been in the making of a classic photograph, we see the true value of editorial judgement, of learning how to pluck the classic shot from a clutch of okay alternatives. Assuming that McCartney was, indeed, the final arbiter of which of Macmillan’s photos was to be “the keeper”, one wonders what George or Ringo, accomplished photographers in their own right, might have chosen. But Fate went the way She went. Inside many of our most casual bursts of frames might lurk an “inevitable”, a picture that cries “it could only ever be thus”. Our judgements after the snap are often the equal of everything that went before it. It’s a long and winding road (again, sorry).

GOODBYE TO ALL THAT

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M AMAZED THAT, AMONG ALL THE MYRIAD THEMED PHOTOGRAPHIC COMPETITIONS the whole world over, that at least one annual contest isn’t totally dedicated to Ruin, a sort of Devastation-Thon of images dedicated to all things ravaged, savaged, rotted, bombed, exploded, imploded, crashed, crushed, smashed, burned, broken, annihilated, obliterated and generally blown to hell. It would not, as you might first assume, be a montage of misery, but a celebration of one of the most consistently appealing subjects in the history of photography.

Let’s face it; ever since we began freezing images inside boxes, we have been endlessly fascinated with the remains of things, the disintegrating aftermaths of global conflict, urban decay, human tragedy. In various ages we have labeled this fascination “realism” or “journalism” or “commentary”, but whatever tags we apply to the practice. we continue our attraction to the visual depiction of destruction and loss. Ashes. Wrecks. Carnage. We chronicle the places where hope has flown, where glory has faded, where victories turned to failures. We and our cameras are always on call When Things Go Wrong.

As storytellers, we are drawn to when the story grinds to a close, when the fresh becomes the trashed. Maybe making pictures of ruin is just half the job of telling the tale of mankind. Beginning, meet end. Dream, meet nightmare. But I honestly believe that we should embrace our role as photographic crepe hangers by hosting a dedicated and curated show of Absolute Misery. It’s more entertaining than flowers, mountains and sunrises, and, as we’ve shown since the first camera started clicking, it’s a subject we cannot exhaust. Or resist.

INVISIBLE BLIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CLEAR BACK IN THE LATE 1940’s, ARCHITECT FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT began correspondence with various agencies and even president Harry Truman to protest the construction of an array of massive electrical towers proposed for the open desert directly opposite his seasonal headquarters at Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona. He was furious at the idea of the pristine view out the front door of his architectural academy being polluted with the sight of the metal monsters, and proposed that the power lines connecting them be buried underground. Wrong century for fighting the westward advance of American infrastructure. The towers were built and Wright reversed the entrance to his retreat, architecturally turning his back on the ugly sight.

Skip forward three-fourths of a century later and views all over the world are still blocked and blighted with the hideous snarl of wires and relays from the 1900’s. It is the kind of visual garbage that, as regular citizens and especially as photographers, we have all learned to not see, rather like looking through a windshield that is so coated with spatters and bug guts that our lacerated eyes simply focus through it all. Moving from Wright’s bailiwick in Scottsdale to Ventura, California nearly two years ago, I found myself with a stunning view out my apartment terrace of the Topatopa mountain range which, like many peaks along the central coast of the state, rises up rapidly from the nearby Pacific shoreline, going from warm sands to snow-capped peaks of well over 7,000 feet in height within just a few miles. It is the kind of view that begs to be captured in a camera, one of nature’s photographic freebies.

Except.

Except that, to my amazement, while composing the shot, I was astonished by the degree to which I simply did not notice that any view of mountains would have to be through a maze of wires. More upsetting than the horrible clutter of the scene was realizing that I had simply become accustomed, over far too many years, to just not seeing them at all. I once heard a Nikon ambassador say that one of his students could have been on an ocean liner, hundreds of miles from land, and still manage to get wires into her pictures. Now, I was that person, instead of the champion of intentional vision that I had convinced myself I was. Given the gorgeous sight of snow across the top of the Topatopas the other day, I’m still glad I took the shot, although it now goes, along with many other near misses, into the Good Idea, But file. In my youth, I held put the hope that that file would shrink somewhat as I grew old and wise in my photographic pursuits. But, as it turns out, the mountain of mastery is always there, day after day, and just as dauntingly tall, no matter how many times you loop around the race track. And learning to look for what you’ve taught yourself not to see, the invisible blight, is part of that daily ascent.

IT’S NOT THE SHOES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WAS RECENTLY READING AN ARTICLE that centered not so much on the unique talent of legendary photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson as on the succession of early 35mm Leica’s that were his go-to tools. In the writer’s defense, I believe he was at least trying to make the case that HCB’s kit merely facilitated his own wonderful vision, assisting but not making his greatest images. However, a reader that already regards certain cameras with the zeal of a cult worshiper could easily come away with the opposite view, that those Leicas were, themselves, a determinative force in how his pictures came out. And that’s unfortunate.

People who sell consumer goods tap into the human habit of crediting things for what might be achieved by intelligent use of those things. Eat this breakfast cereal and break the four-minute mile. Ride around your neighborhood on the tires that won the Indy 500. The pitch even works in reverse psychology, as in Spike Lee’s brilliant ’80’s ads for Nike, in which he kept asking various basketball superstars, “it’s the shoes, isn’t it?” The payoff was, of course, a knowing wink to the consumer, i.e., “well, no, it’s not really the shoes, hee hee, but, P.S., Jordan wears ’em, so…” And, for shooters, the equivalent pitch: buy this camera/lens/attachment/app and become a great photographer. It’s an easy approach for advertisers, because it appeals to our own bias about what creates excellence, which, in many cases, the advertisers have “taught” us to believe in the first place.

Cartier-Bresson, whose sense of composition was said to be so keen that he was known to merely raise the camera to his eye and click in one unbroken motion, developed that economical sense of execution on his own, irrespective of what gear he was using. He employed the simplest, most streamlined approach to making pictures that he could, and, as a matter of historic accident, the early Leica’s, themselves very no-frills affairs, gave him all the machine he needed to get the job done, and nothing more. Other manufacturers could likely have served the same elemental function for him, but, as fate would have it, Leica got there first, and so became an inextricable part of his legend, a lazy kind of “oh, that’s how he did it” explanation for a genius that simply cannot be explained.

One wonders how long the camera industry could thrive if manufacturers could not (a) make us discontented with what we already have, and (b) convince us that the next toy we buy will make us a Cartier-Bresson. But the real “camera” in photography is the one positioned behind our eyes. Knowing where to hit the nail-head is more important than merely buying a premium hammer. It really, honestly, swear to God, is not the shoes.

REALITY ON DEMAND

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ANY TIME I HEAR SOMEONE WAXING NOSTALGIC for the “good old analog days” I am tempted to check their forehead for sign of a fever. Certainly there are elements of the film experience that, decades after the dawning of the digital revolution, I can still look back on with a smile, there are just as many aspects of working in that medium that fall into the “good riddance” category…clumsy, burdensome steps that put ungainly obstacles between envisioning a shot and being able to execute it expeditiously. Strangely, initial reaction to the technical simplification of the making of an image has often been negative, even vehement. For example, many of we elders can still recall the hue and cry that issued from the ranks of the purists when auto-focus was introduced, with direct predictions that true photography was now dead, etc., etc.. blah, blah, blah.

And you can go on down the line, from the math whiz meanderings of light meters to automatic film advance, to, well, make your own list. Near the top of my own “thank God that’s over” roster is the calculation of white balance, which used to require a lot of back-of-the-envelope figuring and is now, like so many other fine functions, an on-demand dial-up. Clicks. I certainly am not downplaying the vital aspect of the right color temperature for the right shot, and, indeed, formal portraitists and studio shooters still have a more essential need for pinpoint precision in this area. But for many more of us, WB is an elective choice made in a moment and largely on a whim, as in the two sunset exposures seen here, taken barely a minute apart from each other. These images are one intentionality level up from straight snapshots, and yet, I can produce drastically different results in an on-the-fly shooting situation where the ambient light is changing rapidly and speed and ease are key.

Cameras are now loaded with many more control options than many of us will need in a lifetime of use, like the now-standard menus of emulations designed to re-create the look of dozens of different classic film emulsions, or custom settings for diffraction compensation. Many of these functions were once, like white balance, slow and tricky to achieve. Now they are a click away. And with the departure of all that bother, another barrier between thinking of a shot and getting it has been eliminated. The purists can, of course, make things harder for themselves out of some affection for “authenticity”. Me, I want to get to the making the picture. Immediately, if not sooner.

LXXIV, OR THEREABOUTS

Through his nightmare vision

He sees nothing, only well

Blind with the beggar’s mind

He’s but a stranger, he’s but a stranger to himself—Steve Winwood, Jim Capaldi

By MICHAEL PERKINS

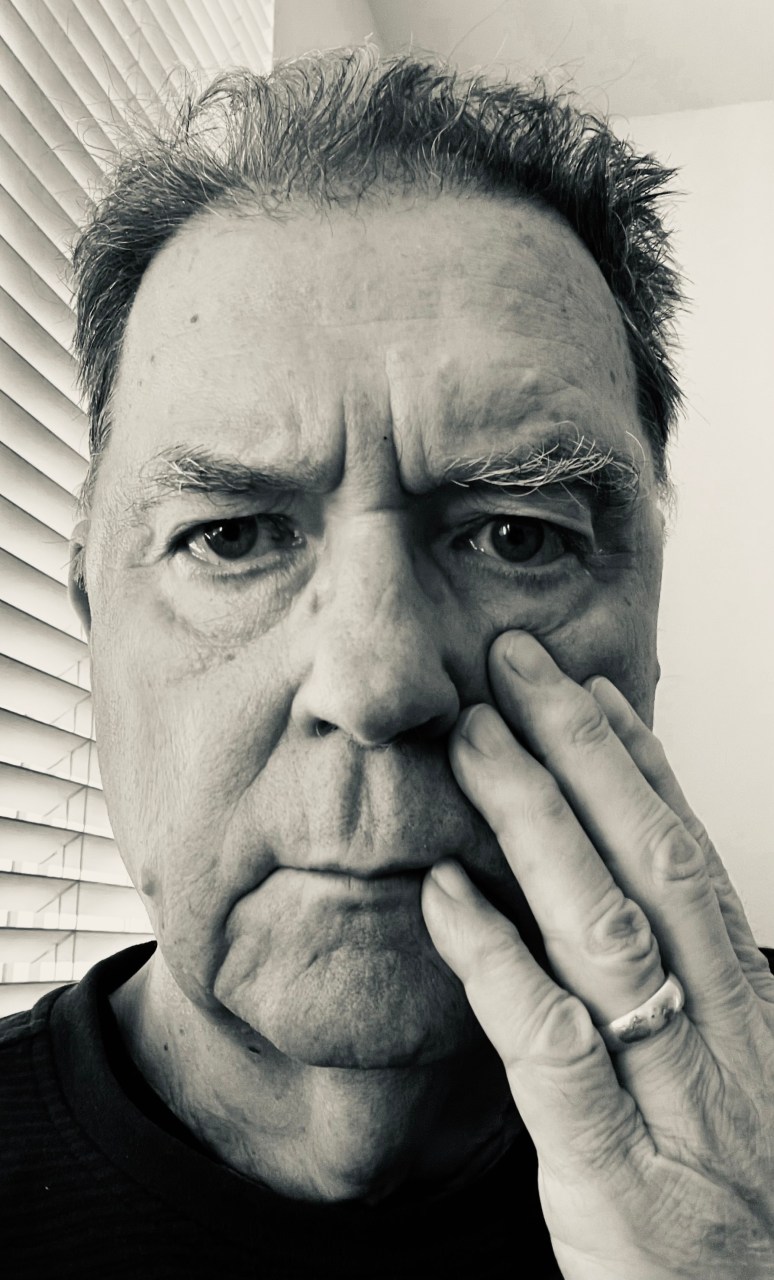

I’VE SCRIBBLED MUCH IN THESE PAGES OVER THE YEARS about the challenge of doing something photographers both big and small do zillions of times per day, with widely varied results; attempt a self-portrait that actually tells the truth.

Knowing the kind of entertaining liar I can be at times, I always mistrust my results, as, when it comes to self-knowledge, I may be the ultimate “unreliable narrator” available for making an image of myself that is honest. Not that I haven’t tried. As decades of birthdays have come and gone, I’ve posed myself in both formal and casual settings, in search of some elusive quality of…. authenticity?……only to wind up feeling like, oh, hell, I’ll get it right next year…..

This time out, this February 8th, I saw the task differently, as I have just spent several months trying to regroup from a series of nerve injuries which included my forearms, a condition that made simple tasks like opening a pickle jar seem herculean. The temporary loss of strength and fine motor function in my fingers was especially depressing, since it wrecked havoc with my ability to operate a camera with any real degree of control. Suddenly, my artist father’s old teachings about hand-eye coordination came back to me in heartbreaking echoes. What if that linkage between what I could see and what I could execute were to remain forever severed?

And so, with mere days to spare before turning seventy-four, for me to actually get 99% of that back….well, it certainly clarified the terms of any birthday selfie I might normally have planned. No big costume changes, no symbolic props, just a simple document that my eye and my hand were back on speaking terms. No other kind of image seemed to make sense; I was crawling out of a hole in which normally conjoined parts of me were not connecting, and there could be no other visual depiction of that reconciliation than documenting the re-establishment of that link. Life, like photography, is often a game of inches, with all of us struggling to have our grasp exceed our reach, and when your fingers occasionally close around those goals, you’ve snatched the greatest treasure in life.

SLOW YOUR (CAMERA) ROLL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE’VE MUSED OFTEN, IN THESE PAGES, on the difference between what I call snapshot mentality and photographic mentality. The first occurs when our minds are in “the moment of the moment”; quick, instinctual reaction. The second speaks to a more contemplative approach to making pictures, something that requires intention, planning, and a number of creative choices. The omnipresent tsunami of gazillions of images generated by the convenience of the mobile camera favors snapshot mentality, while older tech, film for example, bends toward photographic mentality. One approach urges that we do things in a hurry, sorting out the chaff later (if ever), while the other dictates that we slow down and focus.

Several disciplines within photography actually seem to be trying to make photographic mentality a priority. The recent explosion of new medium format cameras, for example, emphasizes careful design of an image rather than quick takes. The retro fascination with film, especially with technically limited toy cameras that are prone to error and failure, also forces the user to stop and think before shooting, if for no other reason than sheer economy (mistakes that don’t matter in digital are costly and time-consuming in analog). Another key demarcation is the decision to shoot on either manual or full auto. which also imposes its own unique methods. And then there are the spiritual or mystical approaches that enter into every creative process, demanding that all shooting decisions promote patience and deliberation, a kind of zen hive mind. It’s like the old predictive primer Megatrends, in which the author argued that, like a pendulum, mankind swings between the poles of high tech and high touch. Once high tech begins to overload our senses with speed or convenience for their own sake, the human need for high tech…..a direct, tactile, and yes, slower engagement with the world, becomes needful as a corrective.

We all do a percentage of our work in both snapshot and photographic mentalities. Neither approach is sufficient for every situation. But there is a lot to be said for stopping, waiting, and evaluating what we are doing on the most complete terms possible in the moment. Photographs never suffer from too much advance planning, after all. And while we all admire the sentiment that we must “stop and smell the roses”, the very first step is to notice that there are roses in the first place.

TOGGLING BETWEEN TRUTHS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

If you can’t do it right, do it in color.——-Ansel Adams

THE MAN MANY REGARD AS THE JEDI MASTER OF PHOTOGRAPHY could be said to have had a sizable blind spot when it came to his preference for monochrome over the course of his long career. Part of his distrust of color came from the fact that black and white afforded him a degree of fine technical control that emerging color systems of his time could not yet rival. Another part of his bias stemmed from the fact that he accepted that mono was a departure from reality, a separate realness that he could manipulate and interpret. In his time, color was closer to mere recording; garish, obvious, and, for him, the opposite of art.

By contrast, the world we live in has been dominated by color images for so long that we can easily develop our own prejudice regarding its opposite….that is, to see monochrome as less than, as if, by choosing not to use color, we are somehow shortchanging our art, performing with one hand tied behind our backs, doing more with less. Of course, black and white photography is in no immediate danger of dying out, proving that it has a distinct and definable purpose as a storytelling medium. Further, mono can, in fact, engender its own counter-snobbery, as if certain kinds of work are more “authentic” because we purposely limit our tonal palette, like writing a minimalist melody. Both views, when taken to extremes, can cause creative paralysis, since there is no way to prove or disprove either argument’s rightness or wrongness. There is only the pictures.

Mono image taken as one of three rapidly snapped frames, each one using a different pre-assigned preset in real time.

Over the past few years, I, like many, have tried to provide myself with several choices when capturing an image in real time. With a number of different film emulations pre-assigned to my camera, it’s easy to erase risk by just clicking from one such custom setting after another, taking the same scene in, for example, a faux Fuji transparency style, a simulated Kodachrome look-alike, and a custom monochrome profile reminiscent of classic Tri-X film. I don’t always elect to do this much coverage on a shot, but there are times when I worry about whether I’m making the right decision in the moment, and so I find the extra coverage reassuring, as if I’m improving the odds that something will work out. There is plenty of room in the photographic world to accommodate more than one kind of visual “truth”, and the most creative of us must be willing to toggle between them with flexibility and ease.

RETURN TRIP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“HEY!!!”

A very young, high and urgent voice from nowhere in particular.

“COME BACK HERE!!!”

Who come back where? Oh, wait, the sound seems to be coming from straight ahead, but I can’t see…

Oh, there’s something….

A small blur with a blue tail on it streaking off to left, followed, an instant later, by a small boy, emerging from the front entrance of a coffee bar that occupies the corner parcel of a retrofitted apartment building in downtown Ventura, California. The blur is, in fact, his dog, and the blue tail is his leash, and boy, is he bulleting out of the joint, heading down the street at Tireless Puppy Speed, pursued by his young master. Me, I’m shooting architecture in the neighborhood at the moment, which is why I find myself directly opposite the java joint, armed with a camera, but too slow to actually catch Fido’s escape. However, I have faith that I will soon get another bite at the apple.

And so I do, as Young Master catches up with the little one within half a block and proceeds to march him back to the coffee shop entrance, giving me a chance to squeeze off a series of shots of the two framed against the incredible blue of the SoCal sky and the lumpy off-white of the long adobe building. It’s a great time of day for long shadows, as witness the shade cast by the wall-mounted sign, but I wait to get the boy clear of that to keep the shot simple; just two small figures against the broad, empty canvas of the building. Young Master is moving at a fairly slow space, giving me the luxury of planning a bit. Frame number three is the one. I have been largely taking pot luck with the other shots of the morning, but this one opportunity redeems all the meh results from the session. That’s the way street work happens; on its own terms, with little notice and just a quick clue that something worth having might be on the way.

Like Tireless Puppy, you just need to sense when a door is opening, and be ready to run.

ALL OR NEARLY ALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A COMMON MISTAKE AMONG CAMERA-TOTING NEWBIE BIRDWATCHERS (a very distinct subset among photographers at large) is to regard their outings as either Successes or Failures, as if they were hunting for deer, or trying to land a ten-pound bass. That is, either I ‘came back with something’, or the morning was a waste of time. Of course, it’s disappointing when either no birds show, or the ones that do show can’t be persuaded to jump into your camera. I have even heard some photogs say that, unless they actually managed to capture an image of a particular breed or species, it doesn’t, for them, really exist. Such people are bound not only to be horribly bad birders; they are also likely to be failed photographers.

To be out in the world in search of a particular thing is to deliberately narrow your concept of what’s “worth shooting”, and it’s counter-productive to why you should be out in the first place; to develop and exercise your eye. Certainly, there will be days when the winged ones seem to be deliberately thwarting you, but who said that they must be the only thing you train your camera on while you’re out anyway? In short, if the birds ain’t happening, what else is? If you’re not trying to answer that question, then your shooting experience will be pass/fail, completely binary. It’s as if you went to a state fair and said you were only going to shoot the hot dog stands. Using that logic, a quartet of naked aerialists juggling flaming chainsaws might pass by you while you held out for a shot of a wiener on a stick. Short-sighted?

Some of the things that redeem many of my birding outings have nothing to do with what I couldn’t find and everything to do with what else was available in the moment. Birdwatching is really about observation, and so, being already in that state of mind, why wouldn’t you also be equally fascinated with whatever else comes to hand? Yesterday I shot over 100 frames, most of them failed attempts at capturing winged subjects that were just having none of it. As birding is usually communal, this left me with a lot of time to fill, since the others in my pack were having better luck or were simply more skilled. As they scored on the feathered column of their scorecards, I shot environmental impressions of a pond we were scouting. It wasn’t what I came for, but I was glad I didn’t write off the entire morning as a “miss”. Photographers obviously stumble upon many naturally amazing scenes that are, if you will, “ready-to-eat”, but remaining open to the less obvious is even more important than a quick win. That’s where your growth comes from. A bird in the hand….

GO-TO / COME-BACK-TO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE URGE TO DO MORE WITH LESS, to make better and images with a smaller central amount of kit to carry around (or invest in), probably hits every photographer at least once in his/her life. It’s great fun to add to one’s arsenal of weapons/toys in the pursuit of being able to shoot anything under any circumstances, but it’s also very freeing once you decide on the absolute minimal amount of gear that it takes to do nearly the same thing. I’ve gone through any number of “return to basics” phases over a lifetime, always looking for that one set-up that’ll keep me from over-complicating the elemental principles for making decent pictures, which are, let’s face it, pretty simple.

This all leads to the search for the so-called “go-to” lens, an ongoing vision quest for me, and, I suspect, for many of you. But there is another, slightly different comfort category, which I call the “come-back-to” lens, a piece of glass that may, at one time, have served as a go-to, and now has earned the right to occasionally return to the front of the pack, like a one-off date with an old flame. A true come-back-to may not be a universal solution to all shooting situations, but it likely will have been proven in battle in some manner at an earlier time, and thus deserves to be deployed again in a similar situation. This goes a lot to the issue of familiarity, of ease of operation, of not having to think too excessively about how to get the pictures you want. The come-back-to is, in essence, a return to comfort. It’s not a box of chocolates: you know what you’re going to get.

So, an example: when I want to set up my camera to handle the shifting mix of light, exposure challenges and color rendition in the tricky environment of, say, a museum, I go digging for one of the oldest optics I have, a 1970’s-era Nikon 24mm f/2.8 manual lens that I’ve used, off-and-on, for about fifteen years. I set my Nikon Z5 on full manual, pre-selecting a medium focal length like f/4, and tell the camera to allow auto ISO to make any necessary tweaks on my sensor up to 3200. At that point, I’m working almost literally with a point-and-shoot, a level of ease that allows me to react to a rapidly changing series of environments without slowing down to fiddle. It’s not strictly logical, but then the advantage of a come-back-to is mostly emotional. I feel as if I’m going to get good results, which is half the battle. A ” go-to” is a lens that can be counted on to do damn well nearly everywhere; a come-back-to is like going home again. Or so it feels to me.

cONFRONTATIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Photography is the simplest thing in the world, but it is incredibly complicated to make it work–Martin Parr

THOSE SHOOTERS THAT WE DUB “STREET PHOTOGRAPHERS” all share a secret; that what most of us casually regard as “reality” is nothing but the top surface on a layered cake, a topography that we drill down into, in order to reveal the profound beneath the obvious. England’s Martin Parr, who passed at the end of 2025, began his career doing straight documentary work, and gradually evolved a whimsical, even gentle mastery of street work that showed everyday people, bearing their social masks, even as it revealed the biases and beliefs that underlie them. In the hands of other photographers, his approach might have been considered rude, even intrusive, but, being British, Parr practiced, instead, a kind of lower-case “C” confrontational style.

Parr, born in 1952, first aspired to be a documentary photographer as early as age thirteen, influenced by the work of the the U.K.’s Royal Photographic Society. Laboring with hit-or-miss grades in school, he found a true home at a local polytechnical academy, joining the ranks of local reporters on any and every kind of news assignment. His first truly personal approach to photographing people came as a result of his move from a city to a rural environment, where he studied the regional rituals and habits of working-class locals in an effort to to develop an eye for the humorous reality beneath their public selves, publishing Bad Weather, the first of what would eventually total over sixty collections of images, in 1981. As he moved from journalism’s then-dominant medium of black-and-white to color, he began to frame his work at a much nearer distance (using a macro lens), creating portraits that in many cases were little wider than head shots.

The range of hues and contrasts in his color shots became even more startlingly invasive as well, as he usually employed a full flash or flash ring at very close quarters. The results were revealing, if seldom flattering. “The fundamental thing I’m exploring, constantly, is the difference between the mythology of the place and the reality of it. Remember, I make serious photographs disguised as entertainment. That’s part of my mantra. I make the pictures acceptable to find the audience, but, deep down, there is actually a lot going on that’s not sharply written in your face. If you want to read it you can read it.”

Parr’s pictures were technically of the faces that his subjects presented to the world, that is, the way they believed they were best seen. His genius lay in recording that curated version of “the truth” while showing the persons beneath the mask, not in a predatory or mean sense, like a Diane Arbus might work, but in a kind of knowing smirk, as if to say, “aren’t we all very silly, after all?”.

Martin Parr’s influence extended to his stints as a lecturer, a documentarian for television, and a university professor, with his images evolving from studies of consumerism and the rising British middle class, as well as studies of global tourism and a half dozen other projects, all done with the effect of stripping away society’s outer veneer to provide a glimpse of the actual motivations that lurked below. “Unless it hurts, unless there’s some vulnerability there, I don’t think you’re going to get good photographs”, he once remarked, adding, “I see things going on before my eyes, and I photograph them as they are, without trying to change them.I don’t warn people beforehand. That’s why I’m a chronicler. I speak about us, and I speak about myself.”

Fotofatigue

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

IN ENGAGING REAMS OF PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGES AT A SINGLE SITTING, the human eye can react like any other over-used muscle in the body. It grows weary, numbed by the sheer volume of information that is often viewed like a shuffling deck of cards rather than absorbed at a leisurely pace. It’s almost as if, having taken these trillions of pictures, we have to pay visual lip service to them by at least trying to view them all. But that method merely wears the mind down, resulting in what I call fotofatigue. We all know, logically, that less actually can be more, but when it comes to looking at images, we act counterintuitively, flooding and dulling our ability to perceive anything deeply.

One thing that can worsen this problem is for us to, like the guitarist in This Is Spinal Tap, crank everything….every effect, every technique, every everything, up to 11. I’m all for taking one’s vision or gear to the limit, just not all the bloody time. Take a specialized lens like a fisheye, which is so ultra-wide that it can render everything it sees in a rigidly circumscribed bubble of deliberate distortion. It is designed for a specific effect, but, like any other specialized look it should not be used in every shooting situation. What starts out as a novelty becomes, in repetition, a “signature” look, and then a crutch.

The shot shown here, shot with an 11mm fisheye renders plenty of realistic detail and depth of field but does not careen fully into circular-for-circular’s sake. It uses some of the flexibility inherent in the lens, but stops well short of turning the garden into the cover art for a psychedelic rock band from 1967. Shredding away on our artistic guitars at 11 is exhilarating, but I believe that the best photographs benefit from at least some degree of restraint, choosing to engage the eye for a more contemplative view rather than merely stab it with the sharp stick of shock. Photographs that merely hit at the speed of ZAP! POW! eventually wear out the viewer, and are easily dismissed and forgotten. Mona Lisa’s smile, small and slight, need not be stretched to engulf the entire lower half of her face just to grab our attention. Her mystery comes as much from what is concealed as what is revealed. Good images should always strive for that.

THIS IS DELICIOUS: WHAT’S IN IT?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE IMAGES THAT POSSESS AN UNDENIABLE TIMELESSNESS, as if, in looking at that particular photograph, you are simultaneously looking at every photograph ever taken, as if the creator has tapped into something unbound by time, a picture that could have been made by anyone, anywhere, anytime. Of course, as artists, we aspire to capture something, shall we say, eternal, even though we work very much in the moment. Those lucky incidents (miracles?) cast a spell upon the viewer, a delicate skein of magic which can only be ruptured by running our mouths.

In today’s technical milieu, in which we can make anything look like anything, from any time, in any style, we are becoming addicted to over-explaining how we got to the finish line. We caption. We asterisk. We jawbone endlessly about our techniques; why we chose them, what the wondrous recipe contains and how you can apply it to your own pictures. How ordinary. How soul-less. Are we artists or cookbook collectors? Hints at how to achieve this film emulation or that vintage look are, I suppose, a source of study for some. But images need to image. The power or impact of a photo needs, finally, to stand on its own. There may be some fascination in how various effects were achieved, but in the end, in a visual medium, that data load is just not that important.

It’s now so long since I made this picture that I would have to deliberately research my data to remind me how I did it. But I won’t be doing that. I don’t need to know what road I traveled to get here. I got here. There is nothing that pulling up all that information can tell me about whether the photo works. Of course, at the time, I had to be supremely concerned with what ingredients made up the soup. But harping on about it now, merely to act as a soft brag about my talents, is just creating more noise in a world that’s awash in it. There is a reason why magicians don’t explain how the rabbit got into the top hat. Let’s incline ourselves, in making images, toward wonder rather than technical blather.

SIDE HUSTLE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOULD I OUT-LIVE MY WIFE (don’t even want to go there, mentally), I have toyed with the idea of changing her epitaph to read, “DON’T TAKE MY PICTURE!”, as it is already miles ahead of any other utterance in terms of her signature phrases. I married a woman whose attitude toward being captured by a camera is on par with every other female in my family. I don’t know if this is down to false modesty (the real message being “PLEASE take my picture”?) or a raging epidemic of insecurity complexes. Bottom line; to catch Marian, I almost always need to catch her unawares.

Jacy At The Rexall, 2026

A recent Saturday afternoon catnap seemed just the vehicle. No posing, no prep, no re-takes, just, boom, this is what she looks like, and I’ll hear no backtalk, thank you. I managed several frames, and was content that I would be the only purveyor of the results, as is many times the case. But the angle and sprawl of her long legs (best in the business) on the living room couch seemed to suggest something very different for the fate of the picture.

With her upper torso completely cropped out and the rest of her upended vertically, her legs and bare feet seemed to suggest something far more sensuous. Here was a woman relaxed in her skin, casual about her appeal, confident in her power to disrupt and attract attention. Thus, “Standing Marian”, in my mind’s eye, now recalled the easy allure of the character of Jacy Farrow, the small-town boy-torturer portrayed by Cybill Shepherd in The Last Picture Show. I could see her standing near the local drug store’s romance magazine, sipping on a bottle of Orange Nehi, all while the local lounge lizards hoped she would glance their way. Just once.

Often the initial purpose we envision for a picture turns out to be just a first draft. There seems to be an assertive energy about some images, such that they will themselves into their final form. If we listen well, we often reap surprises, in that the photo makes us look smarter than we really are. Creatively, it gives you a leg up.

Sorry.

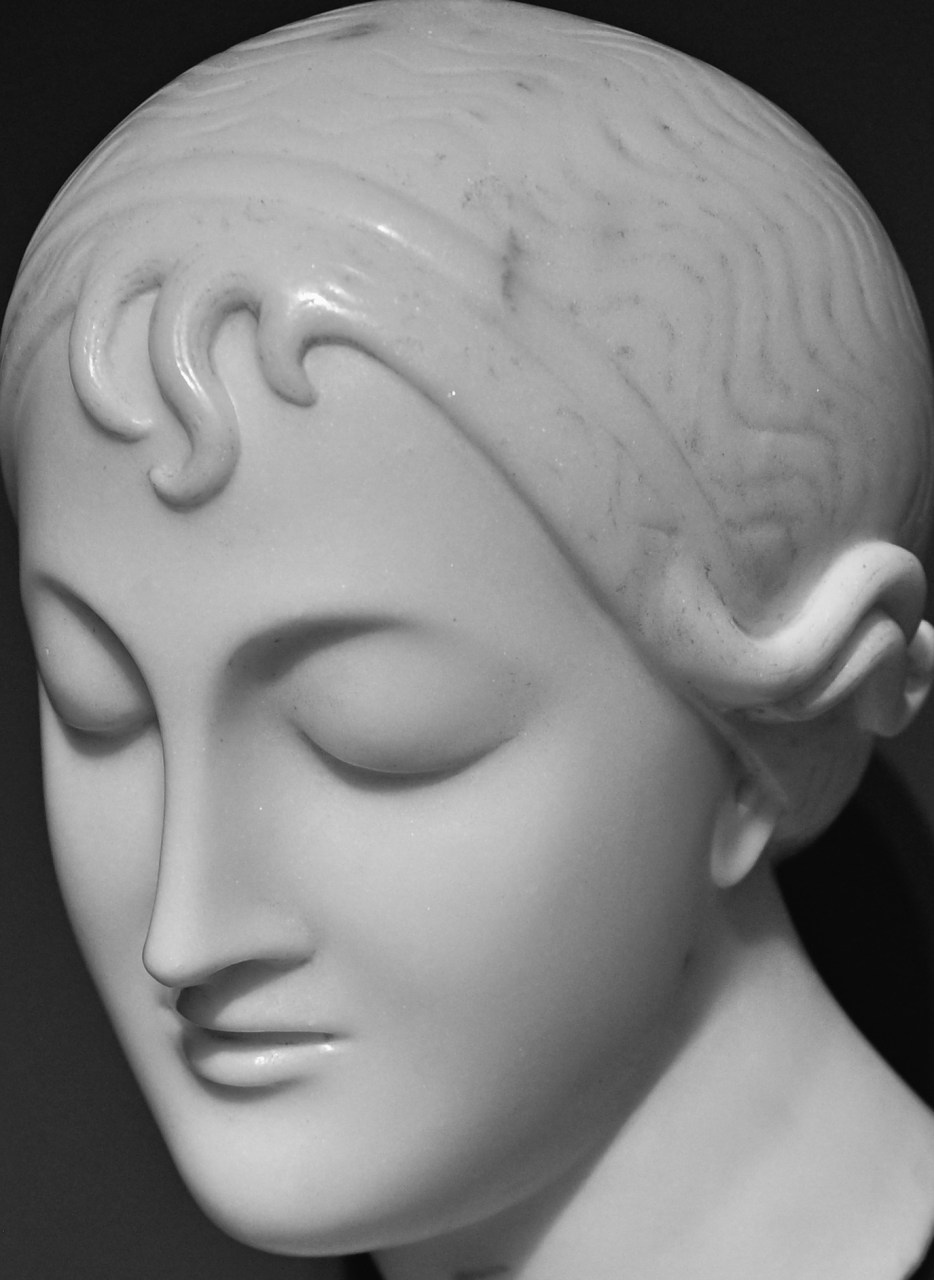

FRACTURED FEATURES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A CAMERA’S RECORDING OF LIGHT FORMS PERHAPS THE MOST CRUCIAL ASPECT of a photographic exposure. The quality, intensity and quantity of illumination quite literally separates the men from the boys when it comes to results. Whatever manipulation the photographer wants to add either before or after the shutter snap (strategies which can totally re-shape an original image), any plan has to be based, first, on how your gear renders color, whether you decide to independently monkey with it or not. You have to be able to first count on what the camera initially sees.

You’ve no doubt compiled your own list of subjects or situations where the available light is, well, untrustworthy if you will, times when you have to take very strict control to obtain what you want. For me, the top of such a list has always been the space within museums, where objects, passages, public spaces and exhibits are subject to what I call color poisoning, caused by tinted glass, reflections, extreme contrast, uncontrolled contamination from competing light sources and more. It’s a mess, and a real working knowledge of how your camera meters and register light in a given place is absolutely essential. Your intentions for pictures of an exhibit or object will often be at odds with the curatorial staff’s, who have their own ideas for what makes a collection look “good”, rather than your needs.

In the case of the images in this article, I have, sadly, admitted defeat, in that they were both intended as color pictures but have been converted to monochrome. This, after many long sessions in which I tried, and failed, to come up with a color registration that I could call honest, given the lighting scheme used in their respective display areas. They may, in fact, actually work a little better in b&w, but that’s not really the point. Thing is, I have had to settle for what you see here, or at least return both shots to the lab for another pass in the future. At the very least, I need to learn more about how to counter the light that’s available to me in a wider variety of situations. I know, duh, but it’s both enlightening and humbling to get frequent, if painful, reminders about specifically what you’re up against, technique-wise.

HARD LEFT, HARD RIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE YEARS WHEN ONE’S PHOTOGRAPHIC WORK displays an obvious path, a palpable pattern of interest that informs most of his/her output. A year of landscapes: a year of macro studies: a year of intimate portraits; and so forth, making it easy to refer to a set twelve-month period as “my beach year” or “my pensive period”, etc.

Looking back at 2025 (which, for those who read this in the future, ends today), I seem to have been all over the place. The closest thing I can see to a clearly defined theme might be my exploration of exposure extremes, a whole bunch of experiments with both boosted and minimal lighting that seem to be largely of the “I wonder what happens when I do this” school of thought. Not career-defining, I admit, but throughout ’26 I seem to have tried frame after frame of exposures that are wildly left or right of the average. The idea, as in any departure from one’s comfort zone, is to maintain some degree of control, as well as having the choice of high or low key justify itself in the resulting image. And, of course, being me, I will, on occasion, also try something counter-intuitive.

For example, a beach is usually a place where you’re looking to shed light, since there is such a torrent of it most of the time. Instinct says to stop down the aperture, quicken the shutter speed, etc. However, I can’t help wondering if I can create a painterly or minimalist effect by going the other way and flooding the frame with surplus light. Counter that with the image I took inside a dark tomb of a theatre during a youth concert. Shooting from over 400 feet away with my particular zoom, I couldn’t open any wider than f/6.3, but I certainly could have created a so-called “normal” exposure simply by cranking the ISO to around 6400, albeit with a little noise. Instead, I dialed in ISO 3200, giving the camera the bare minimum of light needed to make the shot. What was I looking for? A warmer, more intimate aspect? Who knows? The search, the uncertainty, was the objective, even more than the final picture. Again, some photos need to be about what happens when I do this?

If you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always get what you’ve always gotten. Simple, really, and yet we will, against our best interests, bake in habits and rely on their predictability. This year, at least with available light, I decided to spend a bit more time rolling the dice. What I do with what I learned….well, that’s another year.