A FEW WORDS IN EDGEWISE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OH, IT’S YOU…

Or, more appropriately, good to see you….

It’s been far too long since I’ve laid out the welcome mat to all the new subscribers who’ve signed up for updates from The Normal Eye since the last turn of the season. Please excuse my manners, which are more AWOL than non-existent. Obviously, none of this would still be limping along, eleven years on, without you.

TNE was never intended to be a one-way soapbox, or, in fact, any kind of soapbox at all. It started as sort of a diary of my own journey as a photographer, an unsure chronicle that I worried would have little or no utility to the public at large. After all, no one journey is applicable to all, and so I made no attempt to hold myself up as a general guide for technique per se, since everyone and his brother can teach the technical end of the craft far better than me. The blog thus kind of grew into an attempt at a two-person conversation, with my questions about the value of my own progress being thrown out not as an example but as a starting point for discussion. The point wasn’t to write about “how I did it” so much as to try to answer the bigger question, which was why I decided to do it at all.

For me, everything starts with vision and motivation, something I’ve tried to convey every time I sit down to compose this humble small-town newspaper. Tech is fascinating and fun, but, when it comes to art, machines are just machines, something we will all be struggling to remember as A.I. becomes either helpmate or Frankenstein monster as regards our photography. What makes a camera valuable is the eye in back of it, and the soul back of that eye. Getting at least that one point across has remained a constant aim in these pages, and you alone must decide if it has any value for what you’re also discovering about yourselves.

But back to point one; there is no Normal Eye without you, and I don’t re-state that as often as I should. So thank you. For your patience, for your advice, for your passion. And for striving always to see, to see, to see. That’s the entire ballgame.

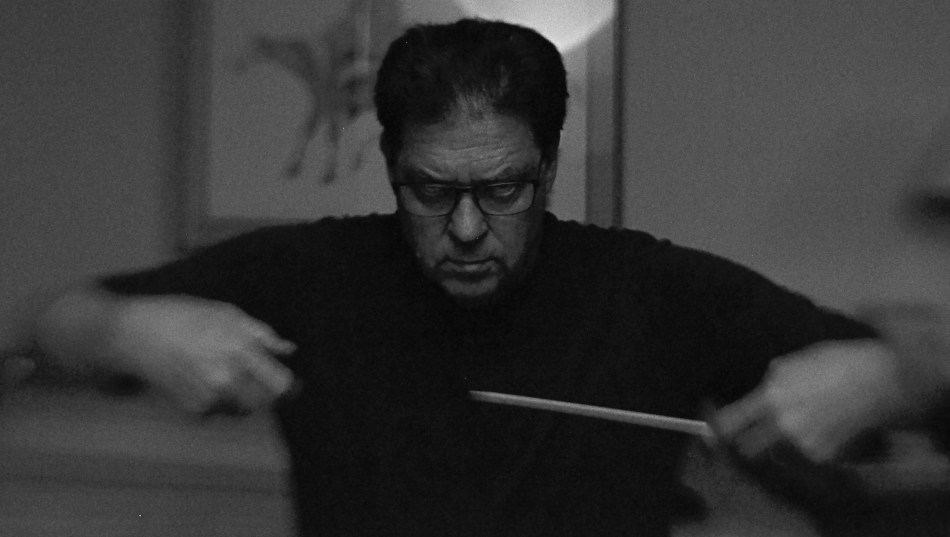

THE SOUND OF NO HANDS CLAPPING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE HEARD A LOT OF HYSTERICAL HAND-WRINGING LATELY over whether anyone can still be a photographer is the age of artificial intelligence, as if the decision were solely in technology’s hands. I believe all this panic is wrong-headed; Art makes a grave error when it assumes that it can be nullified by any force outside the artists him/herself. Creative energy begins within and explodes outward. Its conception is private, sacred and inviolable.

What happens to intellectual property once it lands in the marketplace, legally or otherwise, is a different matter. Battles will be fought, and are being fought (talking to you, Screen Actors’ Guild), to protect a creator’s right to the publication of or profit from his/her work, and that’s as it should be. But while we’re fighting those battles, let’s observe what has happened to the integrity of the photographer already, in just the short space since the dawn of digital and social media.

Conduct your symphony for an audience of one. That’s the only one that matters.

We post and publish constantly, as if that’s all there is to making ourselves “photographers”. We make ourself slaves to approval, spending as much or more time pursuing likes and reposts than we did in the generation of our work. We’ve somehow adopted the idea that all this gratuitous praise will make our work stronger, more “authentic”; worse, we’ve come to embrace the notion that the world is breathlessly waiting for our pictures. Both ideas are demonstrably wrong.

If you’re going to be a photographer, then you must carry your own water. Own your concepts and execute them as best you can, but be prepared to be their only champion. No one is waiting for your next picture, and no amount of self-promotion can improve even a single image if you mangled either the concept or the execution of it. You must concentrate on the making of the picture first, last, and always. You must also face the fact that your best work may have no other jury than yourself, and be okay with that. The poet spoke of “the sound of one hand clapping”, but we must also be content with the sound of no hands clapping.

What makes this all worth re-stating is that worrying about someone (or some thing) stealing your work in the Age of A.I. is a non-issue unless the stuff is worth stealing in the first place. And just as in the case of social media, Art that is produced merely for approval is just pandering. For most of us, the work will have to be enough. Those of us lucky enough to emerge from the pack will find, just as we did in the earlier days of mass production, Xerography and Photoshop, ways to ensure that our pictures remain our work, and ours alone.

OLD AND NEW AND STRANGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS BOTH A DESTROYER AND RE-SHAPER OF CONTEXT. Destroyer, since, by freezing isolated moments, it tears things free of their original surrounding reality, like lifting the Empire State out of Manhattan and setting it afloat in the upper atmosphere. Re-shaper, since it can take the same iconic building and, merely by shooting it from a different angle or in a different light or on a different street, make it seem novel, as if we are seeing it for the first time. That odd mix of old and new and strange are forever wrestling with each other depending on who wields the camera, and it’s one of the qualities that keeps photography perpetually fresh for me.

Take our famous Lady Liberty. It is burned into the global consciousness as one of the most powerful symbols on the planet, and its strength derives in part from the more-or-less “official” way it is photographed. We see it towering above the harbor, mostly from the front or side. Most of our snaps of it are destined to be echoes and recreations of mostly the same way of seeing it that has been chosen by the millions that have gone before us. Its context seems locked in for all time, and that frozen status strikes many of us as “proper” or “appropriate”.

But what does the same object look like if we force ourselves to go beyond the official view? Seen from the back, for example, as seen here, can it be upstaged, or at least redefined, by a refreshment stand or the golden colors of autumn? Do we even think of the statue as being in front of or to the side of or behind or framed by anything? Of course, what you see here is not a majestic picture, as may be the case in the standard “postcard” framing. But can that be valuable, to reduce the icon to merely another object in the frame? Can anything be learned by knocking the lady off her lofty perch, separate from all accepted versions?

Thing is, as we stated up top, that re-ordering of our visual concept of something is a key function of the making of pictures. We not only shoot what is, but what else may be. I’ve spoken with New Yorkers whose daily commute placed the Statue right outside their car window every morning of their working life, eventually rendering it as non-miraculous as a garbage truck or a billboard. For them, would a different version of the figure be revelatory? Making pictures is at least partly about approaching something stored by everyone in the “seen it” category, and saying, “wait….wait…not so fast…..”

GIVE IT TO ME STRAIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’M NOT REALLY CERTAIN IF THE EYE actually has a preferred way to see, factory settings for composition that say “order” and thus facilitate the intake of information. Like you, I have read all the cautionary notes in the how-to books that insist on adherence to certain laws for framing a picture. These tips dictate how to create engaging portraits; how to arrange space for best narrative effect; and, perhaps chief among all of them, a level horizon.

Now here’s where the “rules were meant to be broken” faction in the audience begins to roar its disapproval, as the very idea that art should be subject to rules of any sort is as loathsome as ketchup on cottage cheese. And, yes, I understand that artists gotta art, and that too much formality can be the death of creativity. But then there’s that whole debate (see intro) on how the eye sees, and whether it has a bias toward information that’s arranged in a certain way. Pondering this too long can actually lead to photographic paralysis, a state in which you worry so much about shooting pictures that are “wrong” that you can’t shoot any pictures at all. And, as the Temptations once sang, “that ain’t right…”

Does this look “bent” or “saggy”, or is it just the two martinis I had at lunch?

The idea of trying to put enough “correctness” in the layout of a shot gets tougher the more complicated its subject matter. Consider this image, taken inside a massive conservatory greenhouse. The curved staircase, the arched supports in the ceiling, the standard vanishing points and convergences….all make this composition very, very, complex, and trying to force it to adhere to some kind of calibration or “starting point” by which to engage the eye is tricky. And then there’s the entire discussion over whether I chose a lens (28mm in this case) that is too wide to ensure that the shot is free from distortion, making matters even worse.

The result is certainly dramatic, but perhaps less clear as regards a viewer who is encountering it “cold” without all the mental gymnastics that I put into shooting and tweaking it. And that’s important, because, in a photograph, that’s where my head and someone else’s eye are supposed to meet, to coordinate, if you like. Pictures start in one person’s eye, are transmitted to a machine, and then, at some point, are extruded to become conversations. If you’re lucky. How do we improve our luck? That takes more wisdom than can be contained in the how-to books.

THE PRECIOUSNESS OF VANISHMENT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY, PHOTOGRAPHY’S ORIGINAL PROMISE was to offer something that had never existed before in the history of the world; the seeming ability to capture reality, to make the tyrant Time itself subject to our will. In an age in which every force in nature, from electricity to distance, was being harnessed to the use of science, this prospect seemed logical. We could now, with this device, preserve our lives as surely as we might imprison an inject in a jar, the better to study at our leisure.

Of course, the truth turned out to be a bit more nuanced.

Instead of imprisoning all of time, we were merely snatching away pieces of it, affording us not an entire view of life, but selective glimpses. Trickier still, we found that all our images, even those we preserved and curated, were still connected to their original context. And as time robbed them of that context, as events and people passed into the void, the pictures that were plucked from that daily continuum also lost a bit of their meaning. Ironically, the thing that was designed to explain everything could eventually be rendered an unfathomable mystery.

Most of the pictures we make of our most cherished people show them in the ordinary acts of living. In the main, they are not chronicles of big things or important days, but, on reflection, it may be that very ordinariness that makes them all the more special, more singularly personal. Over our life together, I have made thousands of pictures of my wife Marian, most of them random, reactive shots rather than pre-conceived portraits. This is strategic; she doesn’t especially like her picture taken, and actively disdains most of the results by most shooters. If I draw a comment as positive as a “that isn’t too bad”, I feel I have beaten the game, or, more precisely, that I have managed, in small ways, to show her what I see every time I look at her.

One day she and I, the “real” people that provide the context for all these pictures, will be no more, and a special kind of mental captioning that accompanies them will also go. Will the images have enough value to be more than the anonymous curiosities we now explore from photography’s earliest days? Will these faces be precious is some way even as their foundation myths are vanished?

HEY, LOOKA ME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST PREDICTABLE PHOTOGRAPHIC CLICHES OF CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION consists of the “establishing shot” used in many drama shows, depicting a particularly important locale wherein the action of the show will take place, be it a corporate HQ, a cop station, a courtroom. The site, whatever its purpose to the story, is shot in the widest angle possible, drastically distorting all sight lines and perspectives, as if to get the viewer’s attention in a visual shorthand that announces that something important is about to happen here. And, consistently, the first scene inside these places, shown immediately after, is shot with a much narrower, or, if you will, “normal” focal length. It’s a one-two combination that has become part of the visual grammar of storytelling.

Drama, as it’s artificially created by visual camera optics, can certainly be an effective narrative tool, but it can also become an effect for effect’s sake, a crutch used to juice up a subject that doesn’t deliver enough impact without it. And of course, the use of tech to dress up an essentially weak image is always a temptation, especially since more and more shortcuts than ever before afford the chance to enhance and tweak. And like many giddy sensations, it can evolve into an addiction.

I have been trying to get “THE shot” of this classic biplane for years, trying to tie into its history and mystery by switching lenses, taking different angles and approaches, shooting in both full natural and completely unnatural light, the works. In this image, I’ve resorted, like many TV directors, to photography’s big go-to for instant drama….an ultra wide. Just as in courtroom and cop shows, the distortion, the unreality of this 12mm fisheye is used to give the subject more power than it might have in standard perspective. The nearly 180-degree coverage of the lens also allows me to get the entire plane in one shot, something that’s proved difficult because of the tight glass “hangar” in which it’s displayed. Here, I have tried to render the plane itself in nearly normal aspect, choosing instead to distort the showroom it’s encased in. As always with wide-angles, it’s not totally about getting everything into the middle of the shot, but getting yourself deeper into the middle of everything that you frame. If that sounds like double-talk, well, welcome to the wonderful world of counter-intuitive photography.

I might have fallen in love with distortion at an early age since I was raised on comic books, where cartoonists freely violated perspectives in the service of a story. Comics are by nature gross exaggerations of reality that pass themselves off as plausible substitutes for it. My camera eye may still want to linger in that playland. Sometimes we just want our pictures to shout, hey looka me, and we’re fairly shameless at going for those eyeballs.

THE WAITING ROOM

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE NEVER BEEN THE SORT OF PERSON to derive peace or comfort from most inherited cultural rituals, especially the formalized etiquette we have constructed around death. The trappings of mortuaries and cemeteries offer me no connection with people I have personally have lost over the years; I experience the vibe of such sites distantly, more like an anthropologist might wonder at the rites of a vanished culture that he’d stumbled upon in his studies. And that means that photographing the symbols and structures of such place is purely an appreciation of design, producing no pangs of emotion. I’m just making pictures of things that strike me strange.

Walking into a cemetery, for a photographer especially, means encountering strange juxtapositions. There are the fixed objects that never change, i.e., the headstones and statuary, and then there are the temporary signs that speak to the fleeting feelings of the living, items that briefly intersect with the permanent fixtures; the flowers, messages and other improvised memorials that eventually will be cleared away by the groundskeepers (as will we all) .

Most can be readily understood. And then there is the occasional mystery.

Like a mylar balloon tethered to a stone angel.

Most motives in graveyards are readily decipherable, but I will likely never know what the number 5 shown here means. It is the most private of messages, and a strange mix of the bouncing of the breeze-blown balloon with the fixed, stiff pose of the Comforter. Regardless of whether it’s been 5 years since someone left, or whether they were merely 5 when they were taken, or…or….?, the picture I snapped out of curiosity is a frozen puzzle, appropriate in a space where all things are now frozen. Suspended. Interrupted.

The fact that I explore narrative clues among the graves of strangers is odd, given that I don’t visit the graves of people I actually knew. I may be trying to find some bond between the loss of others and my own, but I don’t think that’s it. I believe it’s just that I love pictures, especially the odd ones, the ones that defy explanation. Visual art is all about dealing with questions, after all; the running box score of what we learn, or don’t learn, from these random instants that we’ve yanked out of time. Sometimes, just having successfully stolen that odd, singular thing from eternity is enough. Sometimes, it does a number on you.

A LAW OF AVERAGES

Alfred Eisenstaedt demonstrated the value of being in the moment, often with the simplest possible gear.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN RECENTLY RE-WATCHING A BBC DOCUMENTARY on the legendary Associated Press and Life magazine photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt, I was struck by how, over his lifetime, he moved steadily toward simpler and simpler equipment, beginning with the bulky plates of early 20th century press cameras and moving on to the sleek and light Leica that helped him created many of his most iconic images. Simply put, as he shot more and more, he carried less and less.

This was a deliberate choice.

“Eisie”, as he was known to peers and subjects alike, chose cameras that worked within the law of averages, gear that, on balance, delivered most of what he wanted most of the time. This eliminated unneeded change-outs of over-specialized kit, adding to the reaction time he needed to capture so many evanescent images of our time. He didn’t specifically disdain formal studio work, nor did he pooh-pooh the use of artificial lighting, and yet he shot almost always in the moment, where the action was happening, and under the conditions prevalent in that moment. That meant using a generally serviceable camera that could perform well virtually everywhere versus packing a crap-ton of extras that might or might not be needed. As a result, his work was divinely human, imbued with empathy, wisdom, and a whimsical sense of humor.

We often get drawn off the mark, in thinking that a given piece of equipment should always be on hand “just in case”, rather than honing our eye and our soul, which is where all the good pictures come from anyway. Purveyors of optical toys can be quite seductive in persuading us otherwise, getting us gear-focused, hungering for the next technical breakthrough, the magic lens or gizmo that will, finally, make us a better photographer. It’s a little like saying that you’d drive nails better with a more expensive hammer. But the spell is strong and it often leads to many people with many closets crammed with many devices, which may or may not yield better results than solid, basic gear.

Eisenstaedt showed time and again that the ability to read conditions in the field, to anticipate, to solidly compose, to know the value of a changing event, can succeed without a shooter having to shovel cash into the constant accumulation of stuff. If a camera does your bidding consistently and eloquently, it is a “good” camera. If your essential needs truly change, those needs will point like a neon arrow to whether you need a technical upgrade. But the best shooters prove in every age that when, as drag race drivers say, you simply “run what you brung” the pictures will most very often find you.

TRAVELS WITH MY NVr-WZ

What the discriminating fictional snapper relies on in the American desert of 1955; Jason Schwartman’s fictional “Muller-Schmid Swiss Mountain Camera” in Wes Anderson’s “Asteroid City”

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

PROP DESIGNERS FOR MOVIES have to walk a bit of a tightrope when creating on-screen objects, dodging copyright laws (unless product placement is truly the goal), redefining the physical properties of things (think planes that could never actually fly) or even crafting plausible gizmos that cannot exist in the real world (think phasers). Combine all these skills with the recent craze for burying hidden in-jokes or “Easter eggs” in movies to reward multiple viewings by the nerdiverse, and you have the special world of fun fakery, a world where, on occasion, the coolest cameras reside, all bearing the NVr-WZ (never was) trademark.

Fictional cameras in film set my inner geek’s heart a-racing, and, judging by a general search of the interweb, I am not alone. A recent entry is the camera that is sported by Jason Schwartzman’s character Augie Steenbeck in the new Wes Anderson hallucination Asteroid City. In the frame above, Augie, said to earn his bread covering various world crises, sports a “Muller-Schmid Swiss Mountain Camera”, which, of course, never existed in any world outside Anderson’s unique 1955 desert-y destination for science dreams and Cold War nightmares. The deliberate fakiness of the device has sent camera lovers into a game of Clue as to its design origins. And, as with everything else debated on-line by camera lovers, well, let’s just say the results are inconclusive.

The labelings on the camera are the biggest part of the fun, with the optic being labeled as a “combat lens” (so…can it not be used to snap, say, family events in peacetime?), and the overall model being referred to as a “Swiss Mountain” camera, as if there may be additional variants for Italian or Greek or Tibetan mountains elsewhere in the product line. And then there is the brand name itself, “Muller-Schmid”, which may or may not be a reference to Joey Schmidt-Muller, a surrealist painter who pioneered a style called New Objectivity in the 1930’s and who invented a term for his work called “traumatic realism”. In fact, Anderson may just have pulled the two names out of thin air, although I doubt it.

Was the Soviet Kiev 4M the inspiration for Augie Steenbeck’s imaginary kit?

A lot of online detective work, however, has focused on the general layout of features on the camera, with most fans insisting that it must be based on a Contax III rangefinder (introduced in the 1930’s), while another large camp is certain that it’s actually more like the cheap Soviet-era knockoff of the Contax, the Kiev 4M (seen just above). Does it matter? Welllll, either a great deal or not at all, depending on your perspective. What does seem consistent is Wes Anderson’s talent for sending cues to our collective subconscious, our inherited warehouse of cultural impressions, and tossing all that data like salad to create new worlds that are alien and familiar at the same time, worlds where a vintage NVr-WZ is the perfect camera for the task at hand.

HERE WE ARE AGAIN FOR THE FIRST TIME

1966: An early attempt at an “atmospheric” scenic, complete with the kind of light leak that a five-dollar plastic toy guarantees. What a long, strange trip it’s been.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE OFTEN MANAGE TO SUCCESSFULLY EXPORT AN IMPRESSION OF A PICTURE from our mind’s eye into our cameras, and ofttimes the result is reasonably close to how we originally envisioned it. Of course, there is always a gap, small or great, between conception and execution, and the life work of a photographer is learning to negotiate that gap, and sometimes, to do battle with it over and over again. Our first tries at a picture may be immortalized on a sensor, but the germ conception remains in our heads for a lifetime.

This means that certain images, consciously or not, periodically re-assert themselves into other “takes” further down a person’s timeline. We actually may take many versions of a “type” of image over years, seeing its design as a kind of baseline, like the chord progressions in Bach’s Goldberg Variations, which act as a steady foundation for an amazingly distinct number of alternate realizations, each unique unto themselves, each anchored by the same central spine of changes. I am now far enough from my earliest pictures to realize that certain pictures demand a return or a restatement as I move through time.

2023: Different path, different time, different camera. But a different result overall?

One favorite theme from my first days with a camera, the old “sunlit path winding back into the forest”-type composition, recently came back to visit (haunt?) me in a stop by almost the same space where I first tried it in 1966. The top image seen here was shot on 620 medium-format ASA(ISO)-rated slide film on a plastic toy camera with a fixed aperture, a plastic lens, and a single shutter speed. The man pausing with his dog on the footbridge was the kind of cue that your brain (and all of the classic how-to manuals) tells you “might make a good picture”, and so I took it. Luckily, the path and the woods got enough light to save the shot, something which was not the case in 99.99% of my woodland tries at the time. The second shot was taken just weeks ago in the same metro park system in the same city, and this time, as I was armed with a Nikon Z5, the decidedly lower available light did not spell defeat, although I confess to having goosed the luminescence of the path a bit afterwards.

Why do some compositions and conditions urge us to repeat, and perhaps, refine our approach to a familiar subject? Is it merely a pang for a do-over, or do we believe, on some level, that we can actually bring something new to an old subject at different times in our lives? I suspect it’s a little of both.

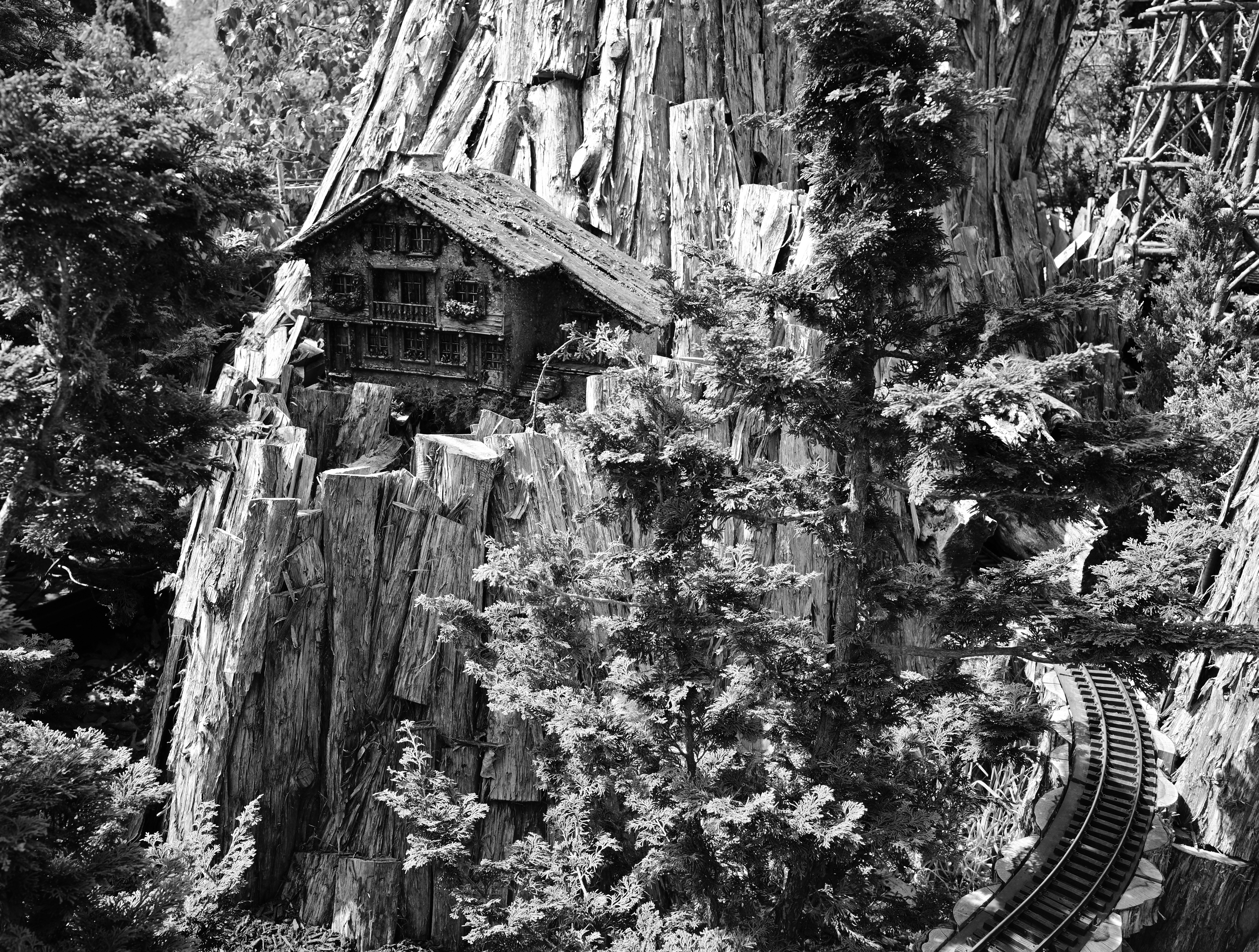

SIZE MATTERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TRICK PHOTOGRAPHY seems to travel along two parallel tracks in its relationship between shooter and viewer. If we approach it in a purely creative sense (Track One), we intend to deceive the eye into believing that the alternate realities we’ve created are plausible, essentially acting as magicians who choose a camera over a wand. The audience is there to be fooled, and we are there precisely to fool them.

In Track Two, however, shooter and viewer are in a kind of winking partnership, in that they are in on the joke. We and they both know we have visually concocted a lie, with each party deriving enjoyment at how clever is the deceiver and how hip are the deceived. There’s no attempt to pass off what we’ve created as “real”, and no embarrassment at having purposely left clues for the viewer, who is all too glad to catch us in our fib. It is this second track which seems to underlie the photographing of miniatures.

Many of us have at least dabbled in shooting scaled-down simulations of various scenes mounted atop tables and pretending to pass them off as the real thing. The audience knows that we know we’re faking, and feel satisfaction at not being taken in, even as both they and us tacitly agree that the object was not to actually deceive. Tabletop tableaux have spawned an entire separate school of lens-making and technical disciplines to aid the illusion, but in two simultaneous directions: making miniatures pass for full-size objects and shooting full-sized scenes of actual objects or people and making them seem like scale models.

In the case of the “mountain cottage” seen here, you’re looking at an intricate, fairly large model railroad layout staged in a public park, which I’ve framed so that it’s easy to either believe that you’re looking at, well, a fake, or, if you prefer, have suddenly been transported to a lonely alpine retreat that’s totally not in a botanical garden at all. Photography is always partly about pitting actual reality against constructed reality, sometimes within the same image, and so, in the service of a good joke, it’s not unusual that you would embrace both the roles of charlatan and sucker. And be happy either way.

ALL TOGETHER NOW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT STARTED OUT WITH MY LIFELONG REGRET at not being able to interview the world’d greatest photographers. Beyond the fact that too few opportunities for actually meeting the greats would ever present themselves in a dozen lifetimes, there was the problem of what, in the name of all that’s holy, I would even ask. Which of them could define, for all the others, what constituted a good picture? Which single person’s work could speak to the full possibilities of the medium? I learned to be content with studying the piecemeal remarks some of them had made, words that often were as evanescent or mysterious as their visual work. And then I realized that they were all, equally, correct.

More precisely, they were all, in an infinite variety of viewpoints, all articulating the same quest, the same terms for their work. Technical mastery, yes, but also personal discovery, a constant struggle to better know one’s self, to hone one’s eye, to synch it with the soul more effectively. I decided to try to show how common this struggle was, across the words of so many shooters, by concocting a kind of “superquote”, a coherent general statement about photography that was actually a composite of the thoughts of many. I served one up in these pages about a year ago, and it was such fun that I offer what follows here as the sequel. As before, different sentences or thoughts originated with different photographers, the identities of which are given, in order of their appearance, in the key below. We are all different, and we are all the same.

Q: How would you (all of you) characterize your personal view of your work?

A: Photography is the simplest thing in the world, but it is incredibly complicated to make it really work. It’s not enough to just own a camera. Everyone owns a camera. To be a photographer, you must understand, appreciate, and harness the power you hold. Only photography has been able to divide human life into a series of moments, each of them with the value of a complete existence. In photography, there is a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality. It’s about finding out what can happen in the frame. When you put four edges around some facts, you change those facts. To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event. The eye should learn to listen before it looks. Photography takes an instant out of time, altering life by holding it still.

Technology has eliminated the basement darkroom and the whole notion of photography as an intense labor of love for obsessives and replaced them with a sense of immediacy and instant gratification. But no matter how sophisticated the camera, the photographer is still the one that makes the picture. The two most engaging powers of a photograph are to make new things familiar and familiar things new. Of course, there will always be those who look only at technique, who ask ‘how’, while others of a more curious nature will ask ‘why’. Personally, I have always preferred inspiration to information.

So stare. It is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long.

(1.Martin Parr 2. Mark Denman 3. Edward Muybridge 4. Alfred Stieglitz 5. Garry Winogrand 6. Henri Cartier-Bresson 7. Robert Frank 8. Dorothea Lange 9.Joe McNally 10. Doug Bartlow 11. William Thackeray 12. Man Ray 13. Walker Evans)

HERE I AM IN FRONT OF…..

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BY A WIDE MARGIN, THE MAJOR BY-PRODUCT OF THE EASE AND CONVENIENCE OF THE DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY ERA has been the boundless proliferation of the selfie. What was, just a generation ago, something of an experimental shot has now become the global baseline credential of personhood. “Today”, wrote Susan Sontag many years ago, “everything exists to end in a photograph”, which I would amend slightly to read “everything exists to end as a backdrop in a photograph of me.” The Eiffel Tower may have some innate impact, but nothing compared to the validation it receives if I am standing in front of it.

Of course, souvenir photography always functioned this way; people always shot Uncle Bob in front of the pyramids or Mom inside Notre Dame, as if to prove that they had made it to this place or that. What’s different now is the sheer volume of shots (and time) spent just in glorifying ourselves, usually in a tight head shot, reducing the attraction or destination in question to a distant prop or afterthought, as if our facial expressions comprised a kind of ego-driven series of trading cards, with the objective being to collect the entire set.

And so we rack up bigger and bigger totals of pictures of ourselves in front of….whatever, and we go from being shooting images of random activity to snapping pictures of people posing for pictures, getting ready to pose for pictures, or playing pictures back. Popular points of interest or tourist destinations roll with the trend and provide more opportunities for their patrons to pose in front of cool stuff. The street performers seen in the above shot do not work for a fair, a carnival, or a circus, but a botanical garden. Traditionally, taking in the seasonal shrubs and flowers does not seem to call for the services of eight-foot butterflies or zebras, but people will or must pose in front of something, and so these wandering backdrops spend all day smiling for “just one more, okay?”

The camera was created primarily as a way to take visual measure of the world beyond ourselves, and, of course, it still serves that purpose. But one of its main components, people-watching, is increasingly about people who are ready for their close-up, self-consciously eager to publish and be liked and be followed. Here I am in front of….hmm, you can’t really tell, but I like the way my hair looked that day….now, here’s…..

BACK TO BEING….A BEING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

VACATIONS ARE HARD WORK.

Well, sure, lying next to the pool and trying to grab the waiter’s attention for uno mas of whatever’s in this drink is not the exact same thing as hard labor. It’s just that, for some of us, effectively getting our minds on a leisure footing requires as much focus as learning any other important life skill, leading many of us to feel that it’s only as we head back for home that we’ve finally started to get the hang of the whole “chilling” thing. And since I am always making some kind of picture wherever I go, the results of my vacay snapping reflect the same process of adjustment as well.

It’s not enough to merely say that the images get “simpler”, or that I shoot more instinctively in some way while on holiday, although both those things certainly happen. It’s more like my entire perception of what a picture is for is changed, along with a different concept of what is worthy of a picture. For one thing, when I am away, I shoot almost equally with a cellphone and my more sophisticated cameras, something I rarely do at home. This affects the choices I make in a variety of ways, as happens whenever we shift from one device’s strengths/limits to those of another.

To cite but one example, I use a much narrower, and sometimes more dramatic range of post-processing effects (of which the picture up top is a product) on my cell camera than on my Nikon mirrorless, on which I nearly always shoot straight-out-of-the-camera. The phone camera also serves as a kind of “sketch pad” or first-take record of subjects I will return to later with the Nikon, whose tools are far more nuanced and controllable. All of this and more goes on in my back brain while my forebrain is telling relax, you idiot.

If I’m lucky, I come home with at least a handful of images in which I somehow managed to do something different, moments in which I actually figured out how to be “on vacation”. In such cases, the expense and planning all seem worth it, and I re-experience at least a part of the electric thrill I felt the first time I put my eye up to a viewfinder.

Now that’s relaxing.

GOING STRAIGHT, WITH A DETOUR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I DON’T PRECISELY KNOW WHAT THE TERM “STRAIGHT OUT OF THE CAMERA” MEANS, and I suspect that you don’t, either.

As a phrase, SOOC is now more the expression of an ideal than any accurate reflection of a process. In the years since on-line file sharing began to codify our photographic work into broad categories (the easier to keep track of things, my dear) this baffling abbreviation has began to crop up more and more. You know the stated intent; to create groupings that are defined by images in which no manipulation or processing was ever added, ever ever, pinky swear on a stack of Ansel Adams essays. But just as with terms like “natural” or “monochrome”, SOOC tends to obscure meaning rather than enhance it; that is, it refers to something that is supposed to be desirable without explaining why.

We are given role models to admire and emulate; legends like Cartier-Bresson are historically held up as paragons of SOOC. The stories are repeated for each new generation: He never spent any appreciable time framing a shot in advance….no editor ever cropped a single one of his shots….and so on, into the realm of holy myth. But so flaming what if all that were even true? What additional authenticity or impact is conferred on a picture just because its author never touched it again after the shutter click? Beyond the wonderful vanity that our first vision of something could be so profound that no further action or intervention is needed to render it complete, does that mean anything more than someone who solved a crossword in under twenty minutes, or managed to go three years without eating dairy? I mean, on one level, I get it. We would all love to claim the mantle of auteur, creating our own perfectly realized art without assistance or adjustment. This my creation, and mine alone. It’s a pleasing fantasy.

But that’s all that it is.

The image you seen here is, by my lights, as close to SOOC as I personally ever get. And yet: I cropped it, leveled it, raised the luminance on the reds and oranges. I did, in fact, mess with it, though not in a majorly transformative way. This is called a “tweak”. Granted, it took a lot less intervention since the master shot generally worked out as planned. The result was a collaboration, if you like, between Shooting Me and Editing Me, and I’m fine with that. Here’s the deal: in creating a “straight out of the camera” category, image sharing sites have, for good or ill, drawn a line between preferred and regrettable, between instinctive genius and “coping well”, and that bothers me. Art cannot be crammed into ill-fitting “worthy” or “less than” pigeonholes. When that happens, it becomes “less than”, well, art.

EX POST FACTO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHING THE BUILDINGS THAT ONCE COMPRISED THE VISUAL LANDSCAPE of a vanished time is always an entire “term paper” project for me. Finding antique structures that were designed for very specific uses, and trying to shoot them in as close to their original form as possible, always trips me into reams of research on how they survived their eras, what threatens their further survival, or what grand new uses await them in the future. And most of those stories begin with my quite accidentally strolling past them en route to somewhere else.

This post office from 1935 popped into view as Marian and I were taking a recent post-lunch stroll around the reborn town of Westerville, Ohio. Photos from its grand opening show it to be nearly identical in appearance to the first day of its service, decades before its namesake was even officially a city. It was one of dozens, perhaps hundreds of village post offices built during the Great Depression by the job-creating New Deal program known as the W.P.A., or Works Progress Administration. Most of the P.O.s erected in those austere years were, themselves, no-frills affairs, devoid of all but the simplest decorative detail and as structurally logical as a Vulcan with a slide rule. Straight, clean lines. Modest appointments. Simple tablatures over the entrance.

The Westerville P.O.’s most distinct feature was actually inside the building, where a “noble work of the common man” mural typical of the period (another federal make-work project to help sustain starving artists) once decorated one wall. Sadly, Olive Nuhfer’s “The Daily Mail” depicted a neighborhood that resembled the artists’ native Pittsburgh, a bone of contention for the Westerville locals who pronounced it out-of-step with the small-town ethos of the area. In time, the painting was removed and returned to a permanent place in the Steel City.

Photographing these kinds of buildings is an exercise in restraint, in that I seek to idealize the structure, to lift it back up out of the past if you life, but without over-processing or embellishing it. Seeing it as close to how it first was is enough for me; it is absolutely of its time, and, as such, it’s a gift.

Post Script (see what I did there?): It’s also encouraging that a regional restaurant chain will soon give the empty building new life as a brew pub. However, it’s more than a little ironic in a town that was once the national headquarters of the Anti-Saloon League, the bunch that forced Prohibition down America’s throat (without a chaser), meaning that Westerville was, for a time, the busiest small postal system in the country, simply by virtue of sending out millions of pieces of anti-hootch literature every year. John Barleycorn gets the last laugh.

OF CLEAN SHOTS AND DIRTY BIRDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“WELL, THAT’S A DAY I’LL NEVER GET BACK” goes the cliche about irretrievably wasted time, muttered after many a dud movie, inert concert or (say it with me), a particularly frustrating photo shoot. Many days we greet the dawn overflowing with hope at the day’s golden prospects, only to slink back home under cover of nightfall with nothing to show for our efforts but sore feet. Such is the camera life.

One of my own key wastes of picture-making time consists of the hours spent trying to do workarounds, that is, outsmarting a camera that is too limited to give me what I want without a ton of in-the-field cheats and fixes. My chief offender over the last five years is the compact super-zoom that I use for casual birdwatching. I lovingly call this camera “The Great Compromiser”, since it only makes acceptable images if the moon is in the right phase, the wind is coming from the northeast, and if I start the day by sacrificing small animals on a stone altar to appease the bloody thing. We’re talking balky.

Out of the murk rises a small miracle. Or not.

The Compromiser achieved its convenient size and insane levels of magnification by writing all its images to a small, small sensor. That means that direct, plentiful sunlight is the only way to get acceptable results, proof of which can only be evaluated in playback, since the EVF is dim and utterly unreliable as a predictor of success. Add to that a maddeningly slow response rate after burst shoots, menus that only Satan himself could admire, and the surety that even a mild boost in ISO will generate more noise than a midnight Kid Rock show, and you begin to get the idea. I saved lots of money by not purchasing a dedicated prime zoom lens and I pay for it daily in the agony of using my “bargain” in the real world. Live and learn.

But just as any camera can deliver shots that are technically, well, caca, an occasionally “wrong” picture somehow works in spite of its shortcomings, and that’s where we find the above image, which gave me a dirty bird instead of a clean shot. The picture’s very imperfections gave me a look that I certainly would not have sought on purpose, but which is strangely endearing, even though nine out of ten other shooters might justifiably consign it to the Phantom Zone.

And so we soldier on, learning to love our red-headed (red-feathered?) stepchildren even as we see them as something that we never, ever want to do again. Love-hate is a term that seems to have been coined specifically to describe how the artist evaluates his art. Get away from me. Come here, I need you. I’ve never despised anyone like I despise you. Kiss me.

Repeat as necessary.

A RESETTING OF SETTINGS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY FIRST QUARTER-CRNTURY IN THE AMERICAN WEST has completely re-ordered my senses, and, in turn, my evolution as a photographer. My concepts of beauty, design, history, and ecology have all been filtered by those years through a visual grammar that is indigenous to deserts and the kind of scale of space that was purely abstract to me as a boy in Ohio. It only makes sense, then, that as I entered the back half of my life, a completely different approach to picture-making would become my mental default.

A recent return trip to my native Midwest, for a longer-than-usual stretch than has been typical for many years, allowed me to schedule more than the standard lunches and reunions with family and friends. That, in turn, let me literally stop and smell the roses, as well as re-awakening my inner tree talker.

This sounds a lot less important than it is, but, in the creation of nature images “back home”, part of me is not only around more green but re-acclimating my eye to the process in seeing it. It’s not as if the West is entirely composed of tumbleweeds and cow skulls; it’s that green takes a back seat of sorts, a reverse of the role it plays in other regions. In returning to the parks and creeks where I came of age, I find myself overwhelmed by the challenges to my work flow; it forces me to slow my shooting time by more than half, if only to re-calculate the regional shifts to the basics of exposure, composition, and so on. I have to find my way back to a sense of belonging here. It’s a fraught journey, made even stranger by memory and other tricks of the mind.

And so it goes. Photography begins as a simple mechanical process, the faithful transcription of experience. But all great pictures begin and end in the brain, and adjusting those settings is far trickier than merely clicking dials on a camera.

REDRAFTING THE RULES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

COMPOSITION IN PHOTOGRAPHY is an exercise in prioritization, a series of ranking decisions that inform the viewer what will be important in a picture. It is, if you like, a picture’s “ground rules”, the terms of engagement between shooter and audience. Look here. Notice this first. Regard these as important.

Most of the time, the assignment of space in an image depends merely on how naturally occurring elements in a photo are framed. The stuff that goes from left to right, top to bottom is thus determined by your shooting angle or distance from the subject. In some special cases, however, a composition is made by extracting select elements in a frame and creating a whole new composition through duplication of those elements; refracting, distorting or multiplying them until the way they occupy space and focus attention are radically re-assigned.

At this point, a standard object becomes purely a bit of design; it fails to be an actual thing and is repurposed as purely a collection of angles, shadows and patterns. As seen in the above image, which was crafted from a standard snap in an airport waiting area, so-called “real” things become components in a fantasy realm through duplication. What they signify or “mean” is completely recontextualized, suggesting worlds that can only exist within the newly re-drafted rules of that one picture.

Often, the unique arrangement of what is framed in a “real” image will supply all the story that photo needs. However, photographers must follow whatever paths lead to the best narrative. And sometimes those paths veer dramatically away from mere reality.

TRANSMISSION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY MOTHER’S PASSING, JUST A LITTLE OVER A WEEK AGO AT THIS WRITING, has understandably released a tornado of feeling, not all of it tragic. More specifically, the portion that is purely sad is actually quite compact; intense, certainly, and at times devastating, but by no means the dominant current in my head. Gratitude occupies the space within my heart far too greatly to yield much real estate to mere sorrow.

Looking over the many images of Mother for use in the usual tributes, I find myself wishing that someone, somewhere, had taken far more pictures of just the two of us together. That unique transmission of energy, hope, and love between parent and child is a rare quality, and is, in photographs, as visually elusive as heat lightning. Candids from birthdays, Christmases and graduations hint at it; few fully capture the entire miracle.

But, this morning, as I was once again bemoaning how few of those grownup-kid transmissions I possessed to comfort me in her absence, I saw that exact energy in a shot I had made of strangers, a single frame among hundreds in a sequence that I had glanced at once and filed away under For Future Consideration. Suddenly that “future” was upon me, as I rediscovered the image you see here.

Like many photos, it’s as evocative for what it doesn’t show as what it does. I can’t tell if this is merely a tender moment, or one in which the small boy is excited, bewildered, tired or just clingy. And nothing of the mother’s face can be seen at all. In some ways, the picture is unfinished, a rehearsal for something more eloquent promised for a few moments later. However, there is the feeling that these two people are, for this one instant, totally sufficient to each other. Their connection is wonderfully profound. They are of each other, and the rest of the world is, at least for now, irrelevant. Looking at it through the filter of my recent loss, the image is no longer invisible to the current me. It’s now an essential possession, something magical that I was luckier than I knew just to witness.

For a moment, looking at the picture, I forgot about reality, and experienced the feeling that I’d love to show it to Mother. But, in her wisdom and her love, it’s nothing, really, that she hasn’t seen before, nothing she and I haven’t lived before. And that’s enough for now.