A.B.W.T.B.S.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM NOT THRILLED WITH THIS PHOTOGRAPH.

However, it could have been a whole lot worse, in that it might never have been attempted at all.

We talk about “no day at the beach”, but on the day this was shot, that’s all I really wanted. My mood found me with no camera on my shoulder, a condition so weirdly rare that my wife, in her very New York sense of sarcasm, asked, “whaddya, sick?” Indeed, it’s not often that I go out photographically inert. I had a camera, but it was in a parked car, a quarter of a mile away from where we were walking. Then I spotted Mister Man here.

The cabled-off area you see in the top shot protects recovering sand dunes (they are living things, trust me) at California’s San Buenaventura State Beach from visitors who might otherwise tramp through them en route to the surf, which faces directly opposite. The approved entrances to the sea breach this dune “wall”, and we had walked through one of them from the parking lot just to walk off some tension when Marian’s binoculars picked up, not your typical gull or sandpiper, but a gorgeous peregrine falcon, apparently scanning the coast for a shot at lunch. “Can you get him?” she asked, even though she knew I was bare-handed. My heart sank. My telephoto was all the way back home, and the Nikon Z5 in the car was only fitted with a 28mm, far too wide for a proper portrait of the raptor. However, after a bit of fussing that the ideal was not possible, I opted for the real, walking back to the car to salvage what I could with the wide-angle.

More “crap” than “cropped”, but you can’t blame a gal for trying…

When we had been near the falcon beforehand, he seemed spook-proof, absolutely rooted to the spot. Passersby and beach patrol wagons had both failed to make him take flight, and, sonofagun, upon our return, he was still there, not flinching so much as a feather. I got as close to him as the steep bank of the dunes and the shifting sand would allow, inching within about twenty feet. Of course, in the view of the 28mm, he might just as well have been in the next county, but I took my shot (that is, about thirty of them). Better to have loved and lost than never to have blah blah blah.

The narrative of the shot, which even at a super-sharp f/16, could not be cropped enough for a really detailed portrait, shifted now, to be about the bird as the sole feature of interest in a wide, rolling terrain. And I can live with that. The old photographer’s advice to A.B.S. (always be shooting) sometimes translates to A.B.W.T.B.S, or “always be willing to be shooting”. No, I am not thrilled with this picture. But I am thrilled for the chance to have made the attempt. Any good batter knows that hits are a consequence of a huge-number of at-bats, most of which result in pop-ups and strike-outs. To get to the good stuff, you just gotta keep stepping up and taking a swing.

HURRY UP AND WAIT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE VERY NATURE OF PHOTOGRAPHY IS THE PURLOINING OF TIME, of snatching random instants from the continuous flow of zillions of moment-drops that compromises the tidal surge of life. We sneak out tiny frozen bits from this flow and lock them in a box, making the moments stand for the totality. Even two-plus centuries into this process, it ought to still strike us as a supernatural act, a miracle.

Because it is.

And since we’re treating time as something we can steal pretty much at will, we can take it a step further, using our cameras to customize the nature of the theft. In freezing an instant, are we snatching a sample of something that was lived in “real” time, or an unreal distortion of it, or a combination of both? In tweaking what is already an illusion (an abstraction substituting for the actual thing), images like this become easy:

Technically, making a picture in which time travels at several speeds at once is pretty much a snap (sorry). The “still” elements are shot at f/16, insuring sharp detail in the people on the bench. The passers-by in the foreground, by comparison, are in constant motion, and, with an exposure of just over 1/10th of a second (which is still “fast” enough to freeze the sitters), they are nearly transparent, and might even vanish into pure blur, were the exposure over, say, a second or so. Thus, in one picture, there are two contrasting captures of the passing of time, or whatever we like to think of as time.

Moreover, when, without a camera, we view this scene in what we fancy as “real time”, picture after picture’s worth of information is refreshed for our eyes every second, making both foreground and background figures appear, of course, to be equally solid, or “moving at the same speed”. What’s the take-home? That our cameras do not see the same way that we do, which makes them a fit instrument to show things that we cannot see without a little manipulation and/or magic. So, when someone says that “photography takes time” they are more right than they know. It takes it, and then it frees it from its bonds. The results are variable. Unpredictable.

Miraculous.

Of Hauntings Great And Small

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS A PHOTGRAPHER, I TEND TO DIVIDE MUSEUMS into two general classes. The first includes the grand halls that act largely as warehouses for collections of disparate items from across history. The second consists of the more personal spaces that were actually once someone’s private dwelling, such as a presidential home or an historic manor. In the first class, the emphasis, at least for me, is on the visual appeal of individual objects, i.e., the mummy cases, caveman tools, etc. In the second class, the narrative lies in the physical space that surrounds the relics, that is, the feel of the house or structure itself.

When I am being conducted through a home where a great family raised its children, where its dreams and schemes were birthed, I of course am fascinated by their quilts, kerosene lamps, butter churns and such. But, since this was a place designed not as a housing for curiosities but as a place where actual people lived, I am interested in trying to show what it might have been like to personally occupy that space. What it was like to wake up with morning light streaming through a bedroom window. What the anticipation of callers felt like, viewing the back of the front door from the second-floor landing. What solitude a certain room might have afforded. Where glad and sad things happened.

Take me to the Met and I will want to see certain things. Take me to an old family home and I will try to depict certain feelings. In the frame seen here, I was lucky enough to be in a bedroom where the delicate lace curtains at left were bending slightly inward from the window, courtesy of a cooling breeze. I began to wonder what it might be like to wake in such a room. What you would see first. How the basics of the room could create a feeling of solidity or safety. My only visual prop was the washstand at right, but that was enough. The suggestion of a life lived was present in just those basics, uncluttered by the mash of curios and collectibles that filled many of the home’s other rooms. Museums sort of represent a variety of hauntings, and their spirits can often speak more clearly in sparse, open settings. It’s like a whisper that you have to teach yourself to listen for. And then the pictures come…..

SNEAKING WITHOUT SPOOKING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

No zoom on hand, and yet I see a potential story happening at the center of a very wide frame. Take the shot anyway? Abso-photo-lutely.

THERE IS A DELICATE BALANCE TO STREET PHOTOGRAPHY, which is really spywork of a kind. Just as wildlife shooters tread carefully so as not to flush birds to flight or startle feeding fawns, street snappers must capture life “in the act” without inserting themselves into the scene or story. Quite simply, when it comes to capturing the real eddies and currents of everyday life, the most invisible we are, the better.

Part of the entire stealth trick is about making sure that we don’t interrupt the natural flow of activity in our subjects. If they sense our presence, their body language and behavior goes off in frequently unwanted directions. Undercover shooting being the aim, then, it’s worth mentioning that such work has been made immeasurably easier with cel phones, simply because they are so omnipresent that, ironically, they cease to be noticed. That, or perhaps the subjects regard them as less than “a real camera” or their user as less than threatening somehow. Who knows? The thing is, a certain kind of visible “gear presence” is bad for business. That said, telephotos can become attractive simply because, shooting from longer distances, they are easier to conceal. But is that the One Best Answer?

Same story, severely cropped, but with more than enough sharp detail to deliver the central idea.

To carry as little gear as possible as well as keep things simple, I mostly do “street” shots with a fixed wide-angle prime lens, meaning that I simply won’t have a telephoto as an option, nixing my ability to hang back from a great distance undetected. And yet I seldom feel handicapped in staying fairly far from my subject and just shooting a huge frame of what could be largely dispensable/ croppable information once I locate the narrative of the shot within it. In fact, shooting wide gives me the option to experiment later with a variety of crop-generated compositions, while shooting at smaller apertures like f/16 on a full-size sensor means that I will still have tons of resolution even if half of the shot gets pared away later.

Another consideration: besides being bulkier/easier to spot, telephotos have other downsides, such as loss of light with each succeeding f-stop of zoom, or having problems locking focus when fully extended. Your mileage may vary. The top shot here was taken with a 28mm prime. about a hundred feet away from the water’s edge, but the cropped version below still has plenty of clean, clear information in it, and it was shot at half the equipment weight and twice the operational ease. These things are all extraordinarily subjective, but on those occasions when I come out with a simpler, smaller lens, I don’t often feel as if I’ll be missing anything. For me, the first commandment of photography is “always be shooting”, or, more specifically, “always take the shot.”, which means that the best camera (or lens) is still the one you have with you.

TO SEE THE SEA IN FULL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM VERY NEW TO DAILY LIFE in California. After decades of longing to convert my occasional doses of this marvelous state into the stuff of everyday experience, to go layers beyond mere vacation sensation, Marian and I have actually done it, making a new home in Ventura, a mid-size city along the Pacific coast about fifty miles north of Los Angeles. This means that the ocean is something we don’t just perceive as a getaway or a holiday destination. It’s something we see nearly every single day.

And once you’re a local, especially a photographer local, you see things that go far beyond the gorgeous sunsets and the lapping waves, including several things you wish you could un-see.

This dessicated pelt, a lunch opportunity for shorebirds and scavengers along the Hollywood Beach, was once a young sea lion. Its bones now picked clean down to the very contours of its skull, it is, sadly, also a more frequent sight for those of us walking the area coastline. Hundreds of sea lions have been washed ashore to suffer and die this year along the California coast, poisoned by an invisible scourge happening silently out to sea. A compound called demoic acid, a species of plankton, is in a state of high surge at present. That is to say that chemical changes which typically convert very small amounts of it to a deadly neurotoxin are currently churning it out like crazy. Fish eat the algae that contains it, apparently without harm to themselves, but sea lions eat the contaminated fish, and the result is an epidemic of sea lion death in San Luis Obismo, Santa Barbara, Ventura, and other coastal towns.

The process by which these toxins are produced in bulk is called upwelling, which occurs when the right combination of colder water meets the right amount of nutrients. Upwelling seasons are a part of oceanic life, occurring randomly since the beginning of time. But what’s puzzling to science, and deadly for mammals like the sea lion, is the increased frequency and intensity of such toxic “blooms”, which may very well prove to be yet another sinister side effect of climate change.

California has so much of its life anchored to the seasons and cycles of the sea that such threats are front and center for policy and abatement, meaning that the state is already seeing things the rest of us have not seen, making match-point decisions that will eventually echo across the great middle of the nation. But to know a thing is happening, we first need to see it happening. Cameras are great for vacations. But we are also obligated, now and going forward, to also use them to bear witness, if not to head off destruction for ourselves, then to chronicle, for our wiser children, what fools their forebears once were.

STAX OF WAX

By MICHAEL PERKINS

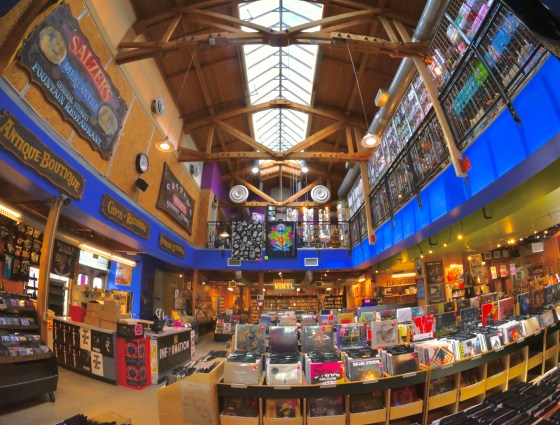

PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO HAVE STRADDLED THE LINE BETWEEN DIGITAL AND ANALOG, doing most of their daily duty as dedicated pixel peepers but occasionally dipping their toe back into film, should certainly sympathize with those who, in recent years, have reverted to the comfort of dropping a needle onto a vinyl record, even if they themselves haven’t invested in a new turntable or a disc-washing device. Heading back to the happy land where experiences were a little more tactile can, indeed, be a lovely little side trip into comfort. For me, however, as a music lover who has long since divested himself of the bulk and maintenance of tangible tune storage, it’s not so much the worship of vinyl that interests me: it’s the places where the vinyl worshippers go.

Salzer’s Records, est. 1966, Ventura, CA

One of the most welcome side benefits of the rebirth of records is a surge in dedicated record stores, not the measly music departments niched into Sears or Targets but places designed just to sell vinyl, and lots of it, along with bongs, t-shirts, and other headgear. The Sam Goodys and Licorice Pizzas and Peaches of the world may be long gone, but a new crop of repurposed shop spaces in re-gentrified neighborhoods is springing up in their place, alongside the few hardy survivors from the First Great Golden Age of Wax, such as San Francisco’s amazing Amoeba Records, Minneapolis’ Electric Fetus, and, as seen here Ventura, California’s Salzer’s Records, originally opened in 1966 and still so huge that, even using a fisheye lens, it’s impossible to show its entire two-story interior in a single shot.

Upon entering, you can smell the patchouli oil and incense, returning you either to your hippie roots or your favorite fantasy of what that era might have been like, depending on your age. Most remarkable from a photographic point of view is that the elder LP shops still exude the same energy as when we were all tender little flower children: the idea of music as but one component in a total immersion into creative energy, a tribal coming together of sounds, smells and sensations. Admittedly, it’s hard to capture all that in a camera, but, like blindly pulling out a random album from your library and slapping it on the turntable, you just drop the needle, and see what happens.

Far out, man….

YES, CHEF!

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Photographers are often instinctual artists, like the cooks in your family who have never cracked a cookbook in their lives but who know, deep in their gut, that, in their hands, a pinch of this or a dash of that results in culinary perfection. They perform without a net with a mastery that seems magical. Other photographers are like chefs, building recipes through exacting amounts, precise steps, and critical timings. Both kinds of shooters “cook” their way to miracles with their own individual approach to the kitchen, and both create amazing delicacies.

When I am in my “chef” mode, I love to play with the many “recipes” touted online by various photographers, endless customized lists of pre-sets that can be dialed into your camera’s brain ahead of the shutter snap, many stored in modes that can be summoned with a click of the function wheel, allowing the shooter to change his/her mind in an instant, as well as giving him/her a whole series of comparative variants on a scene in a way which was, well, impossible in the pre-digital world.

The ergonomics of my camera allow me to dial up as many as five different customized modes (beyond built-ins like, say, Aperture Priority) without taking my eye away from the EVF, guaranteeing me almost the same exact composition across multiple shots, each taken with their own exposure, metering and white balance ingredients. This gives me true choice in a real-time environment, which is perhaps the greatest luxury in shooting with today’s cameras.

The top image seen here of an architecturally stark pizza joint in Ventura, California is the product of a faux-Kodachrome recipe stored on my Nikon Z5’s “U2” mode, while the second shot is a decent re-creation of the old Kodak Tri-X monochrome film (tweaked to simulate the use of a red filter) and shot with a recipe I had stored on “U1”. Both shots have their points, and whether the image works better in color or mono is a battle for another day, but the point is that, with today’s gear, no one has to calculate these looks from scratch while they’re trying to shoot. Nor do they have to wonder whether a scene would look better with a certain look. They can just dial it up, do it, compare, judge, and shoot again, all while the light is right and the subject is still there in front of you. Somewhere my 12-year-old self, armed with a $5 plastic box camera equipped with one shutter speed and a single aperture, is popping champagne corks.

SUNSET ON MY SHOULDER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOMETIMES IN PHOTOGRAPHY, AS IN ANY OTHER ART FORM, the only way to break through to new creative ground is to run in the opposite direction from your inherited viewpoint. We’ve spoken in these pages about the problem of finding anything fresh in a subject that’s been “seen to death”, such as a familiar landmark that nearly everyone has snapped in the standard “post card” view. This is why it’s really tough to show anything new about an Eiffel Tower or an Empire State Building. To honor such subjects in a unique or personal way, you really have to tear them to shreds, reassembling the pieces into some totally new configuration. Replicating what everyone else has done usually fails as an homage and just becomes a replication.

This need to destroy (in order to create) extends to conditions as well as objects, things that might include, for example, an ocean sunset. Face it: we’ve all had our take on that kind of image, and sadly found that, while nailing the technical execution of it is not that tricky, finding any new thing to say with such a shot is truly daunting. Beginning 2024 as a new resident of coastal southern California, I was tempted, a few weeks ago, to do my “official” version of an amber, dusky sundown scene along the coastline near Ventura. The results were not bad, but they were also undistinguished, like asking thirty actors in a row to recite the soliloquy from Hamlet, most of them meriting an “A” for execution, but a “D” for originality.

In the case of my own dusky dilemma, it was only when I turned my camera in the opposite direction, i.e., away from the setting sun, that I found something halfway interesting to play with. As the light faded beneath the horizon to the north, the sun began to tattoo a golden glow onto the metal plate mounted on the side of a lifeguard station facing south. It was very much a thing of the moment: three minutes before I shot the frame, the light was only bright: then, for a brief moment, it burned with a fierce intensity. Another three minutes later, the entire structure was muted in shadow. The image you see here, then, is much more about the delicacy of capturing a fleeting moment than a standard static sunset shot, a picture of things that can easily be lost, disappeared. In other words, what a photograph is for.

The standard ways of seeing things are our photographic comfort zones. We make pictures of what, from our sense memory, we think a thing ought to look like, since it’s much harder to see things and places as if we have never seen them before. Familiarity may not necessarily breed contempt, but, in the making of pictures, it very well might breed predicability, which can actually be worse.

PICTURES OF PICTURE TAKERS OF…..

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS SPEND A SIGNIFICANT AMOUNT OF TIME marking the passing of various elements of their world. We chronicle the end of stuff.

Things go out of fashion. The mass mind discards ideas or ways of doing this or that. And technology, that rocket sled of change, surges madly forward in ways that keep even the most alert shooter’s eye spinning like a top.

Film, as one example taken from our field, is always about to die off, never quite breathing its last, but rising from one potential deathbed after another, always in danger of winking out forever, never quite doing it. One thing that has, in fact, shrunk nearly out of sight, however, is the list of places where film can be served or processed. In my lifetime, dedicated film/camera stores were common elements of daily life, like post offices or drugstores. Now the holy temples where film still reigns supreme are vanishing into dust in favor of mail-in or online resources. And, on most days, in digital’s second quarter century, that’s usually enough to serve a solid but diminished analog audience.

Dexter’s Camera, Ventura, California, May 2024

But I am just sentimental enough to want to make pilgrimage to where the magic is still actually made, where emulsions and paper and controlled conditions combine to produce a tangible product. Even as I myself reserve film for special projects, I treasure a trip to an honest-to-God camera shop like an archaeologist yearns for a walk-through of Tut’s tomb. The image here resulted from my recent visit to Dexter’s Camera, which has done business at the same address in Ventura, California since 1960, with no end in sight. Well, nearly no end. As I write this, the business address of Dexter’s has moved a few blocks away, meaning that you are looking here at a physical photographic space which now can only be experienced, well, in photographs. Pictures of people and places that make pictures. Film is dead, long live film.

RE FOCUS, JULY 2017: THE WORLD FROM QUEENS

SPHERE ITSELF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CULTURAL ICONS, which burn very distinct patterns into our memory, can become the single most challenging subjects for photography. As templates for our key experiences, icons seem to insist upon being visualized in very narrow ways–the “official” or post card view, the version every shooter tries to emulate or mimic. By contrast, photography is all about rejecting the standard or the static. There must be, we insist, another way to try and see this thing beyond the obvious.

Upon its debut as the central symbol for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the stainless steel structure known as the Unisphere was presented as the emblem of the peaceful ideals put forth by the Exhibition’s creators. Under the theme “Peace Through Understanding”, the Uni, 120 feet across and 140 feet in height, was cordoned off from foot traffic and encircled by jetting fountains,which were designed to camouflage the globe’s immense pedestal, creating the illusion that this ideal planet was, in effect, floating in space. Anchoring the Fair site at its center, the Unisphere became the big show’s default souvenir trademark, immortalized in hundreds of licensed products, dozens of press releases and gazillions of candid photographs. The message was clear: To visually “do” the fair, you had to snap the sphere.

After the curtain was rung down on the event and Flushing Meadows-Corona Park began a slow, sad slide toward decay, the Unisphere, coated with grime and buckling under the twin tyrannies of weather and time, nearly became the world’s most famous chunk of scrap metal. By 1995, however, the tide had turned; the globe was protected by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and its rehabilitation was accompanied by a restoration of its encircling fountains, which were put back in service in 2010. The fair park, itself staging a comeback, welcomed back its space-age jewel.

As for photography: over the decades, 99% of the amateur images of the Unisphere have conformed to the photographic norm for icons: a certain aloof distance, a careful respect. Many pictures show the sphere alone, not even framed by the park trees that flank it on all sides, while many others are composed so that not one of the many daily visitors to the park can be seen, robbing this giant of the impact imparted by a true sense of scale.

In shooting Uni myself for the first time, I found it impossible not only to include the people around it, but to marvel at how completely they now possess it. The decorum of the ’64 fair as Prestigious Event now long gone, the sphere has been claimed for the very masses for whom it was built: as recreation site, as family gathering place..and, yes, as the biggest wading pool in New York.

This repurposing, for me, freed the Unisphere from the gilded cage of iconography and allowed me to see it as something completely new, no longer an abstraction of the people’s hopes, but as a real measure of their daily lives. Photographs are about where you go and also where you hope to go. And sometimes the only thing your eye has to phere is sphere itself.

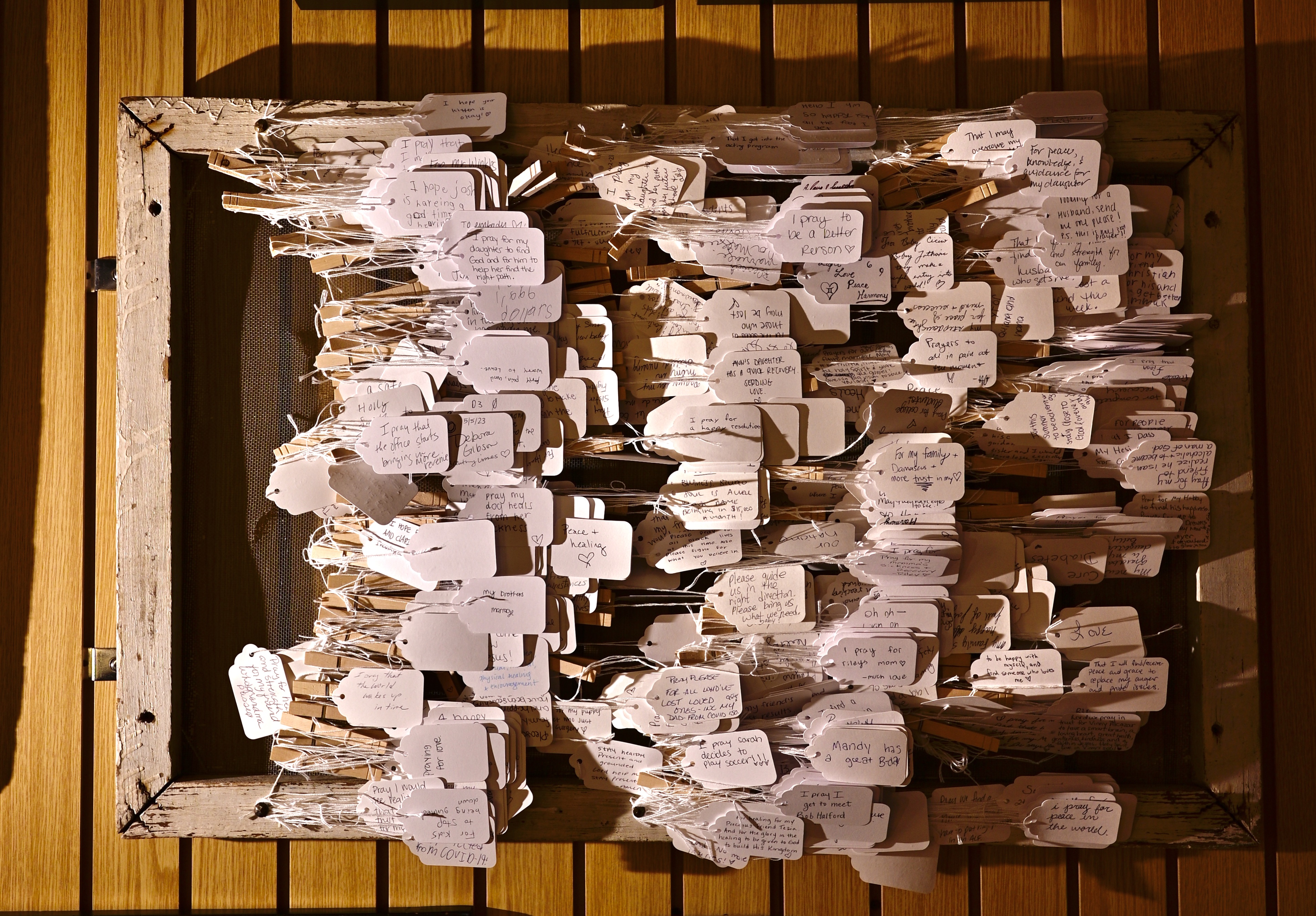

90 DEGREES OF ENTREATY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ALL PHOTOGRAPHERS HAVE A DEFAULT ORIENTATION.

I’m not talking here about political bias or sexual preference. No, this stray thread of thought is all about which way one natively holds a camera for most of their work. I myself instinctively compose for landscape, even when I am actually creating a portrait. This may come from the first camera I owned that shot in anything other than square format, giving me a giddy feeling of liberation at being able to frame an image with surplus information on the left and right.

I realize that in an era now dominated by cell phone photos, I may be increasingly in the minority, especially following the Tik Tok revolution, which is portrait-dominant in a major way. I must confess that many TT videos leave me a bit claustrophobic , as if I am hemmed into a world in which I can’t “look around” inside the image, but that’s the way the platform performs, and so be it.

But orientation is not merely determined in the moment a shot is taken. On occasion, long after I’ve captured something that I feel I “nailed”, I find that a mere ninety-degree tilt can open up the interpretation of a picture, as seen here. This “wish-prayer” collection (top image), actually a framed piece of art that I saw in a gift shop, originally appealed to me because of the dense jungle of shadows created by the cascading layers of tags as seen in one-sided natural light. However, later on, I considered that perhaps the real story of the picture was the viewer’s access to the individual messages of hope, that maybe the photo’s “truth” was all the board’s accumulated entreaties and one’s ability to more easily read them. Ninety degrees later, the entire impact of the photograph has been altered, changing the emphasis from mere design to a straight narrative. I like the image both ways for very different reasons.

But, then again, it might just be my orientation.

SHUTTERING THE LAB

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MANY PHOTOGRAPHERS HAVE LOCALES THAT ACT as muses, triggers for their creative processes. Ansel Adams had Yosemite; for Walker Evans, it might be the streets (and subways) of Manhattan; and, of course, Paris inspired Eugene Atget to tell its story through indelible chronicles of its vanishing streets. As I prepare to leave Arizona after twenty-five years, the scene of most of my photographic crimes remains Phoenix’ amazing Desert Botanical Garden. Created as a nursery for the most unique plant life in the country, it has provided me with the breeding ground for thousands of images taken in every season, in every kind of light, and across the entire range of human emotion. It has, simply, been a laboratory where I go to work on the project of making myself into a better photographer.

I’m still not really “done” with the DBG, but the feeling of leaving something unfinished that I’m experiencing actually cements its place as a legit muse. Even the cacti and trees that I can practically find blindfolded along its paths still reveal new secrets to me, as they have done since I first vacationed in the area in the mid-90’s. From then til now It has been a testing ground for a slew of different film stocks, over six different cameras, countless lenses and a crazy variety of processes and approaches, from HDR to minimalism, analog to digital, soft-focus to low-fi. I’ve shot pictures of quiet contemplation and audacious art installations; I’ve taken casual snaps of awestruck visitors on winter vacations and pensive portraits of native “Zonies” who have made it their personal retreat. Most importantly, the garden has become my go-to playground, the most reliable place for me to stage my pictorial equivalents of an off-Broadway premiere.

The images I have made there, for better or worse, are a reliable road map of every major turn in my development as a photographer over a quarter century. All my light-bulb moments, my moods, my breakthroughs, my barriers. It’s all there amongst the aloes and the ocotillos, the starched plains and the insistent pops of floral color set against the restrained hues of the American desert. Life, death, joy, disaster, and above all, discovery…all of it has happened on these paths. Does that somehow make it the “best” place to take pictures? Well, that’s a very personal thing. Finally, it’s not about whether a particular place is of universal interest or appeal to everyone with a camera. The fact that it acts as a lab for kitchen–testing your concepts is enough, serving as a launch pad for your most perfect, most serious work.

HOLDOVERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE ARMY OF LABORERS, reporters and lookers-on that sift through a millionaire’s lifelong horde of loot at the finish of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane share several emotions, among them amazement, curiosity, and. flat-out bewilderment at the sheer acreage of stuff acquired in the name of mere desire. What is this junk? Who would want it, or, more to the point of it, so damned much of it? One of the workers charged with cataloguing it all makes note of yet another Venus de Milo statue found in the obscenely vast field of material debris, while another remarks that $25,000 is “a lot of money to pay for a dame without a head”. In the end, all of Kane’s accumulated wealth amounts to little more than booty, transferred from place to place until it becomes merely a massive mess left behind for others to clean up. And, as film lovers will recall, his most valued possession, buried in mountains of clutter, accidentally goes to the furnace, up the chimney in a curling billow of black smoke.

That same feeling of bewilderment will hit anyone who clears a house before moving out of it, sparking the nagging question, why did I keep this? In some cases, we actually know why, but in many others, the mystery lingers unanswered. And as I look, here, at the books from a life defined by the love of books, I know the story behind many of them. Why I bought them, what I gleaned from them, what made me drag them from house to house over a lifetime. But, then there is the other pile, the “Venuses” that won’t make the jump to the next home. Those aren’t shown here because, frankly, it’s a bit embarrassing to (a) ponder just how bloody many of them there are and (b) to confront the fact that books cling to me like barnacles to a ship.

No one quite understands the process, but it’s safe to say that, as a narrative, my life “story” is always in dire need of an editor. And so, for a photographer, another set of choices emerges, as a home of twenty years is de-constructed, piece by piece, and there is a strong urge to, as with Kane’s minions, catalogue at least the process if not the meaning of it all. To look upon the weird temporary still-lifes that are springing up all over the house and wonder if there are any Rosebud sleds lurking in the depths. Or should it all just go to the furnace?

LATE ARRIVALS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FIFTY-TWO YEARS AGO, IN 1972, FRANK SINATRA RELEASED the most experimental album of his career. Watertown, a unified song cycle or “concept album” rather than a random collection of individual tracks, was devoid of the hip glamour of the Rat Pack, running cross-grain to everything the Chairman Of The Board’s fans expected of him. As a consequence, The album sank like a stone.

Watertown is a study in the isolation and despair inside the Great American Small Town, as told through the eyes of a man whose wife has left him to care for his two small children alone, her dreams unknowable, her grievances uncertain. Several of the songs center on the center of the town, the local railroad depot. The nexus of comings and goings. Hopes. Disappointments. Soft escapes. Quiet desperation.

Recently, my mind travelled back to my student film days, when Watertown was new and I used its opening song as the soundtrack to one of my four-minute Super 8 epics, shot in my mother’s birthplace of Wellston, Ohio, a place which spent much of the 20th century and all of the 21st slowly sliding into oblivion. Years later, the film is long since lost, but, thanks to a critical re-evaluation and revised appreciation of Watertown, the inspiration for it, as well as newer images, survives, as Sinatra intones:

Old Watertown

Nothing much happenin’

Down on Main

‘Cept a little rain

Old Watertown

Everyone knows

The perfect crime;

Killin’ time

And no one’s goin’ anywhere

Livin’s much too easy there

It can never be a lonely place

When there’s the shelter of familiar faces

Who can say

It’s not that way

Old Watertown

So much excitement

To be found

Hangin’ round

There’s someone standing in the rain

Waiting for the morning train

It’s gonna be a lonely place

Without the look of familiar faces

But who can say

It’s not that way

Sinatra, a singer known for signature albums like Only The Lonely, collections that wrung every last drop of sadness out of the particular kind of heartbreak that is America, really swung for the fences with Watertown, making more of a solid commitment to contemporary material than was typical in much of his later years. Half a century on, many critics have realized what a treasure the doomed project really was. There’s also a lesson in there for photographers, or anyone who ventures into unknown territory. Even when the trip seems to go nowhere, the journey is often worth the taking.

LAYERS AND LIFETIMES AGO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE ALWAYS THOUGHT OF NEW YORK YEARS in the same way we often refer to dog years. Like Fido and Spot and Shep, the greatest city on earth crams a lot of living into every page of every calendar. A year away from Manhattan is enough for what I call The Eternal Facelift to have razed millions of memories and paved them over with shiny new ones. Neighborhoods you admired as Up & Coming on your previous visit are now yesterday’s scenes, with the focus shifting to confer Hot District status on what were, just a breath ago, ruins. New York, where American theatre was birthed, is itself like some eternally running Broadway show that is perpetually in revival. Now appearing in the role of The Apple is… The Apple, Revisited. Held over. Tickets still available at popular prices…..

As I write this, on Easter Sunday in the Year of Good Lord 2024, it has been nearly five years since I set foot on those streets, an insanely long sensory drought for a gent graced, for nearly two decades, with the chance to visit at least twice per year, sometimes more. Marrying into a family that called a place home that Midwestern, landlocked corncob me always regarded as an unattainable fantasy has gifted me with the privilege to see the place through the eyes of natives rather than from a double-decker tour bus, and that, as Robert Frost said, has made all the difference. Sadly, as it did for the locals, Covid-19 started the new decade off by turning us all into terrified house cats, scrubbing the cooties off our counters after the groceries were delivered by ghosts in hazmat suits, collapsing into cocoons of hoodies and p.j.s, waiting for the resurrection.

Perhaps this Easter Week has made me more conscious of transitions, as has the unfurling question of my immediate future, as Marian and I make preparation to leave our home of more then twenty years for a new perch in California, or about as far away from NYC as you can get without walking into the ocean. It’s sent me flipping through an endless trove of images collected by countless walks uptown, downtown, midtown, from towers, bridges, dark dank subway stations and bright, glistening new steel fingers jutting up into the sky. I don’t mind saying goodbye to my immediate environs in Arizona, but boy howdy how I’d like to spend just a fat weekend in, as the locals call it, The City, just to convince myself that it’s still there, still morphing and mutating, still living to defy the odds and confound the naysayers and hayseed haters. After all the places I’ve lived and visited, my heart tells me that America largely boils down to West and East Coast, with a vast vaporous something occupying the space in between them. I have read a lot of the books within the country’s library, and it’s still the bookends, the left and right bowers, that are most real to me, and to whatever eye I’ve acquired with a camera. It’s a strange truth to arrive at, but there it is. And so, toggling between two shores, am I.

SHOOT IT AND BOOT IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S BEEN NEARLY TWENTY YEARS since the last time I changed residences, and the process of taking inventory of the trail of quaint trash accumulated over that period is both hilarious and humbling. Hilarious, because I recognize a lot of stuff that I somehow justified bringing along the last time I moved, and humbling because I hadn’t heretofore acquired the discipline required to just consign much of it to the dustbin. It’s not merely a case of asking “what was I thinking?” once and being done with it, but, in the present sorting process, posing that question several dozen times each day.

One way to calm the emotional unease of parting with stuff that you can’t logically justify hanging onto is to make formal photos of the items on their way out. We are physically downsizing our total household load of chazerei by quite a lot on the way to a much smaller joint, a process which makes it easier to make quick keep/trash decisions than if we were relocating to same-size digs. That strikes a lot of purely sentimental things off the list right away, like china my wife has carried from house to house simply because it’s always been in her family (top) or souvenirs of the 1939 New York World’s Fair (below) that I retained in hopes of someday creating a massive showcase display, a project which I now realize only exists between my ears. Some bits are old friends, automatically transferred to each successive house or apartment over decades. Many of them cannot accompany us on this one last adventure.

We will probably recall a lot these passing bits in detail for as long as our minds remain intact. For those that we have partially forgotten, there will be the pictures. For those that we have totally forgotten, there will be more room for other things in the crowded attic between our ears. In any event, there will be far less weird lore for our children to sift through later, wondering, as they go, what the devil this or that thingamajig was used for, or who in hell would want to hang onto it. There again, the pictures may provide a clue. Or not. And so it goes.

LAST IMPRESSIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THIS WEEK, AS I PREPARE TO MOVE OUT OF ARIZONA after twenty-five years, one of the things that will be hardest to leave behind will be my eleven years as a mentor and guide at Phoenix’ astounding Musical Instrument Museum. I have done a lot of volunteer work here and there over the years, but no other assignments compare with the miraculous gifts I have received on every single day of service at MIM. And that also covers the creations of a heaping helping of photographs.

You would think that, after tracing millions of steps over the museum’s vast layout, often with camera in hand, I would have somehow found “the” picture, the image that captures the blessings that this place have conferred upon me. There are pictures of every hall, every meeting room, hundred of exhibits, and thousands of objects in every kind of light, snapped on every imaginable occasion, from concerts to field trips, training sessions to corporate events to award celebrations. There are wide-angles, selective focus art effects, fisheyes, macros, and double exposures, taken with every piece of kit in my arsenal. And yet, after wading through all that in an attempt to draw a line under all my years there, I find that it’s one of the first, almost accidental photos I made in my inaugural year that still has the greatest impact on me.

The guide shown here is instructing a young girl on how to play the Theremin, one of the earliest practical electronic instruments from the 1920’s, and the earliest influence on synthesizer pioneer Robert Moog, who taught himself its magical circuitry by making repairs on surviving models when he was fresh out of college. It’s also the only instrument in MIM’s collection that must be played without touching.

As the image indicates, one needs to be taught how to position one’s hands to create a bit of electrical connection between the device’s two steel poles (which both oscillate at distinct frequencies) and whose silent transmissions can create both audible volume and pitch variations when guided by the player. Explaining the theremin would require a separate technical essay, but that’s not what the picture is “about”. It’s about the wonderment that is playing across the face of the small girl, no doubt a young woman by now, possibly with girls of her own to astound. As I head for the museum’s exit one last time, it is this moment that I will remember, because all of us spent every day in joyful pursuit of That Face. A-Ha moments. Lightbulb moments. I couldn’t capture all of the wonders every day, either by trying to explain them to guests or by photographing them. But this time, this one time, I got lucky, and something magical jumped into my box.

Which is, really, what keeps all of us coming back for more, camera in hand.

Because, at the end of the day, you might go home with a miracle.

And that is music to everyone’s ears.

ALONE BUT NEVER LONELY

Every photographer in history has been where you now are, that is, staring into a huge question mark.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ART IS AT LEAST PARTLY PRODUCED TO BE SEEN, to act as public testimony to the artist’s ideas, a record of his having passed this way. And there is a natural need for that work to be evaluated by others, to be perceived as a common thread in the overall fabric of the human condition. I see a thing, and I make something that comments on or interprets that thing. And I hope you see what I see.

The problem for art, though, in our increasingly public lives, becomes an exaggerated need for our work to not only be seen but to be approved of. When we post or publish in this age, we are not really looking for a debate or analysis of what we’ve created. Instead, what we seem, increasingly, to be seeking is validation. Likes. That’s a danger to any fully realized sense of art.

Art is solitary. Art is lonely. And the truest of it is generated when we trust our inner pilot light, even when, especially when, no one else “gets it”, or puts a star next to it, or tells us how wonderful we are to have made it. As artists, photographers inherit both the instinct to follow one’s own North Star and the desire to be told how much we are loved. Both urges are normal, but it is the second one which can get us into trouble. I was recently reminded of how grounded Ernst Haas, one of my very favorite photographers, always remained, how he consistently reminds us, through his writings and interviews, that the work counts all by itself, irrespective of result or reward. One quote especially echoes in my head in moments when I worry about “getting it right”:

Every work of art has its necessity; find out your very own. Ask yourself if you would do it if nobody would ever see it, if you would never be compensated for it, if nobody ever wanted it. If you come to a clear ‘yes’ in spite of it, then go ahead and don’t doubt it anymore.

We live in an age that is increasingly defined by how we are regarded by others. And that can make us pre-edit ourselves on the fly, choked by worries about how our work will “play”, as if that had anything to do with why we really do it. So, go, make pictures that may or may not ever garner you a smidgen of approbation. The essential honesty of that act will imbue your work with something that can please you beyond the power of any “like” or heart icon. And that, over time, is all you need to sustain you.

ONE AND A HALF EYES

The settings stored on the “U1” mode button on my Nikon Z5 instantly produce this classic mono effect.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OF ALL THE OCEANS OF INK SPILLED, OVER THE LAST GENERATION, on stories about the debate between photography’s analog and digital camps, relatively few have centered on the most salient difference between film-based and sensor-based devices, which is that the latter are truly miniature computers. Digital has never been about merely finding non-mechanical means to measure light, but truly about an explosion in options, tech that allows the shooter to store thousands of choices outside his own brain, creating, in effect, a database of preferences that he can call upon to instantly render any look he imagines. It’s like adding an extra half an eye to the two you were born with.

The stored “U2” settings deliver a pretty good Kodachrome fake.

Consider, as just a single example of what’s hanging from these new super-tool belts, the “user” buttons that come with nearly every camera on the market, slots where dozens of specific settings that add up to a particular “look” for an image can be stored on a mode button that, when dialed up, immediately creates that look without the need for further adjustment. Of course, in the film era, we could manually make many such custom adjustments, but they required doing so in the moment, one image at a time, cutting the implement time for shots and practically guaranteeing that many moments would simply be lost in fiddling. But now, since we make pictures with a computer, it’s nothing at all to sculpt all those elements, from focus to ISO to tonal range to, well, anything, and park them on a button that’s as easy a go-to as Manual, Shutter Priority, or Aperture Priority. Click to the user mode “button” that you’ve previously programmed, and go.

Another mode (“U3”), another tweak, this one miming an early 90’s Fujichrome slide film.

In my own case, my Nikon’s U1, U2, and U3 modes are programmed to three different kinds of film emulation. U1, seen at the top, is a monochrome look very similar to Kodak Tri-X, with contrasts and resolution that are much keener than anything straight out of the Auto mode. U2 is a pretty good approximation of Kodachrome, a recipe I copped from various online pundits, and U3 is dedicated to a fair facsimile of one of my favorite Fujichrome slide film emulsions. The beauty of having these modes pre-loaded is that, in those confusing moments when I’m unsure which approach to take with a given subject, such as the early morning hotel room seen here, I can crank off three “takes” on it very quickly, comparing them all to my fourth likeliest option of full manual in just a few seconds. This is the heaven of carrying a third half-eye in your pocket: the ability to shorten the lapse between what you see, what you shoot and what you get. It’s a menu of possibilities that no film camera ever afforded me, and further proof, as if I needed it, that this is the absolute best time ever to be a photographer.

DRAMA BY DEGREE

A typical wide-angle shot (28mm) of a subject where mostly all proportions are rendered normally.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WATCH ENOUGH COP OR LAWYER SHOWS, and you’ll see it: the establishing shot which shows the hero’s home base, be it the local police HQ, the county courthouse, or an Uber-powerful law office, stretched to angles of ultimate exaggeration by super-wideangle lenses. Normal optical proportions may be used for all other shots that follow in the episode, but that kickoff image, like as not, will make the locales seem larger than life, seething with drama. Something important is happening here, goes the message. The look is a perfect photographic blend of effect and intention. We want these particular buildings to look unreal, simply because outsized things are occurring within them.

In everyday photo work, however, we often tend to use an effect for its own sake because, well, it looks so cool. We aren’t really justifying all that distortion and surreality with any narrative purpose. We fall in love with the custom look of selected optics, for example the bend-stretch of an ultra-wide, without always asking ourselves if their use serves any other purpose except, “I like it”. I fully cop to this in my own case. I sometimes go from discovering how to master the technical use of an effect and slide easily into the habit of shooting damn near everything with it, until, eventually, I come to my senses.

Same subject, taken from the same distance, but with an ultra-wide, 11mm diagonal fisheye. One question comes to mind: why??

After indifferent luck over the years with variously priced “fisheye” wide angles, I decided to lay off the enclosed circular framings that they delivered, as the bending at the edges, not to mention the color fringing and uneven sharpness, seemed claustrophobic to me. Then, last year, I discovered the very different experience of shooting with a so-called “diagonal” fisheye, which renders a rectangular full-frame image with a wider area of bending at the perimeter. Problem was, I was so relieved to finally get the kind of nearly panoramic images I had been seeking for so long that I started applying the look to things that, for the sake of visual story-telling, don’t really call for it. I was, in effect, shooting too many normal buildings and making them look like Shot One On A Cop Show.

The two images seen here, shot on a 28mm wide-angle and an 11mm diagonal fisheye, show that the features of the hotel in the images are not particularly well-served merely by giving it the Silly Putty stretch treatment. In fact, it actually draws attention in the wrong direction. For me, there is always a risk that, during the break-in period for a new piece of kit, I will mistake the novelty of the results for a true all-purpose go-to approach to shooting any and everything. Eventually I sober up, but, while the high lasts, my work can go a bit giddy. Such is life.