FRACTURED FEATURES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

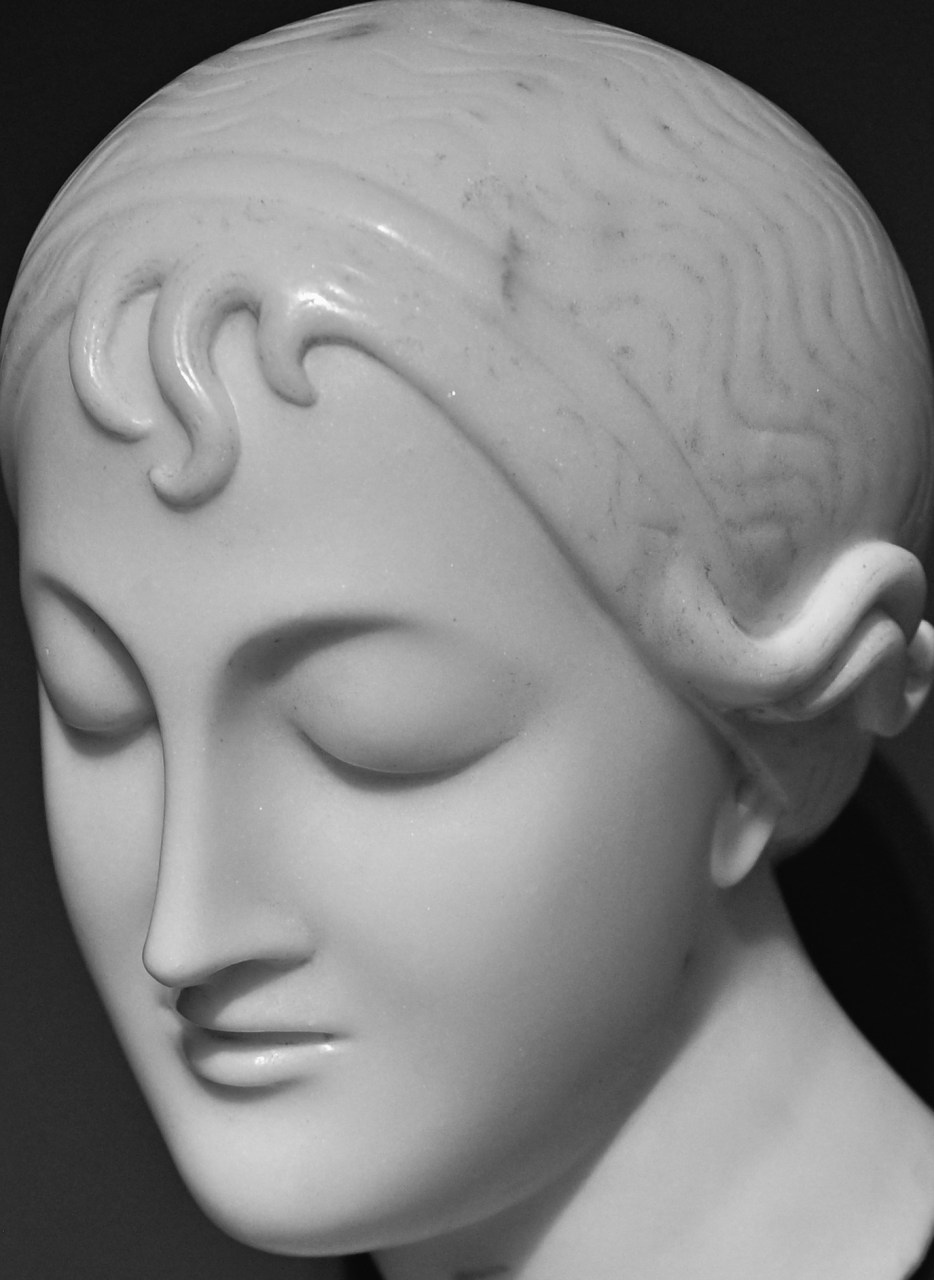

A CAMERA’S RECORDING OF LIGHT FORMS PERHAPS THE MOST CRUCIAL ASPECT of a photographic exposure. The quality, intensity and quantity of illumination quite literally separates the men from the boys when it comes to results. Whatever manipulation the photographer wants to add either before or after the shutter snap (strategies which can totally re-shape an original image), any plan has to be based, first, on how your gear renders color, whether you decide to independently monkey with it or not. You have to be able to first count on what the camera initially sees.

You’ve no doubt compiled your own list of subjects or situations where the available light is, well, untrustworthy if you will, times when you have to take very strict control to obtain what you want. For me, the top of such a list has always been the space within museums, where objects, passages, public spaces and exhibits are subject to what I call color poisoning, caused by tinted glass, reflections, extreme contrast, uncontrolled contamination from competing light sources and more. It’s a mess, and a real working knowledge of how your camera meters and register light in a given place is absolutely essential. Your intentions for pictures of an exhibit or object will often be at odds with the curatorial staff’s, who have their own ideas for what makes a collection look “good”, rather than your needs.

In the case of the images in this article, I have, sadly, admitted defeat, in that they were both intended as color pictures but have been converted to monochrome. This, after many long sessions in which I tried, and failed, to come up with a color registration that I could call honest, given the lighting scheme used in their respective display areas. They may, in fact, actually work a little better in b&w, but that’s not really the point. Thing is, I have had to settle for what you see here, or at least return both shots to the lab for another pass in the future. At the very least, I need to learn more about how to counter the light that’s available to me in a wider variety of situations. I know, duh, but it’s both enlightening and humbling to get frequent, if painful, reminders about specifically what you’re up against, technique-wise.

HAPPY-EN-STANCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S FAIR TO SAY that photographers are occasionally the worst possible judges of what will save or spoil a picture. Try as we may to judiciously assemble the perfect composition, there are random forces afoot in the cosmos that make our vaunted “concepts” look like nothing more than lucky guesses. And that’s just the images that actually worked out.

All great public places have within them common spaces in which the shooter can safely trust to such luck, areas where the general cross-traffic of humanity guarantees at least a fatter crop of opportunity for happy marriages between passersby and props. At Boston’s elegant Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the surrounding walls of the central court are the main public collecting point, with hundreds of visitors framed daily by the arched windows and the architectural splendor of a re-imagined 15th-century Venetian palace. The couple seen here are but one of many pairings observable in a typical day.

The pair just happens to come ready-made, with enough decent luck assembled in one frame for almost anyone to come away with a half-decent picture. The size contrast between the man and the woman, their face-to-face gaze, their balanced location in the middle arch of the window, and their harmony with the overall verticality of the frame seem to say “mission accomplished”. I don’t need to know their agenda: they could be reciting lines of Gibrhan to each other or discussing mortgage rates: visually, it doesn’t matter. At the last instant, however, the seated woman, in shadow just right of them, presents some mystery. Is she extraneous, i.e., a spoiler, or does she provide a subplot? In short, story-wise, do I need her?

I decide that I do. Just as it’s uncertain what the couple is discussing, it’s impossible to know if she’s overhearing something intimate and juicy, or just sitting taking a rest. And I like leaving all those questions open, so, in the picture she stays. Thus, what you see here is exactly one out of one frame(s) taken for the hell of it. Nothing was changed in post-production except a conversion to monochrome. Turns out that even the possibility of budding romance can’t survive the distraction of Mrs. Gardner’s amazing legacy seen in full color, and the mystery woman is even more tantalizing in B&W. Easy call.

As we said at the beginning, working with my own formal rules of composition, I could easily have concluded that my picture would be “ruined” by my shadowy extra. And, I believe now, I would have been wrong. As photographers, we try to look out for our own good, but may actually know next to nothing about what that truly is.

And then the fun begins….