By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT TOOK ME OVER HALF A LIFETIME OF STUDYING WHAT I CONSIDERED THE “GREATS” OF WORLD PHOTOGRAPHY to realize just how biased my own eye was, how it was inclined to see all cultures mostly as my own culture was inclined to see. The first images I loved were basically travelogues, that is, scenes from so-called “foreign” nations, as interpreted almost exclusively by Western photographers. “My” people, looking at “their” worlds, traveling afar and coming back to me with stories whose truth I took at face value.

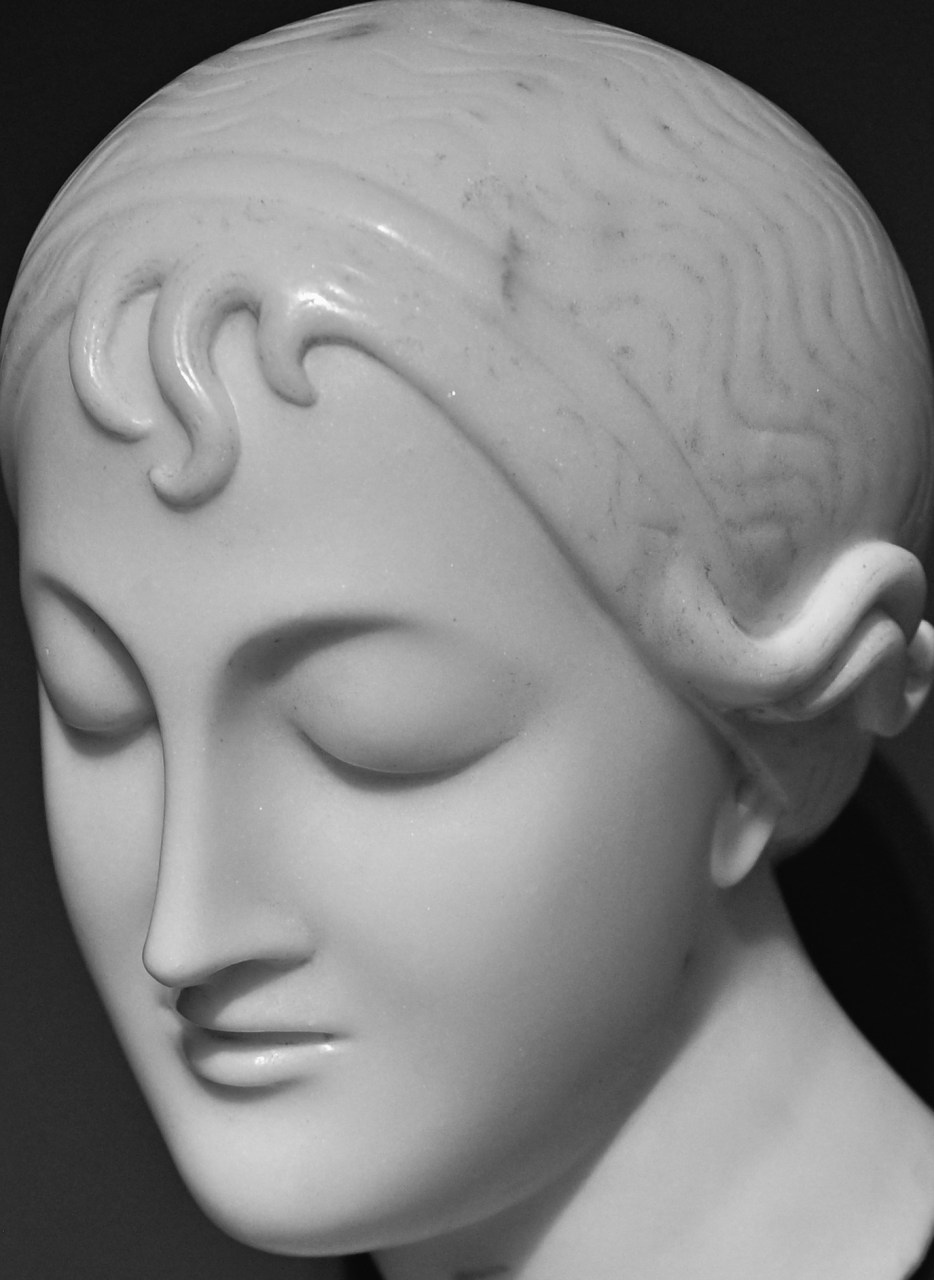

It has taken me a long time, too long, to seek out the visions of people my cultural prejudices regarded as “the other”, to delight myself in the storytelling of indigenous people reporting and commenting on their own worlds, instead of waiting for outsiders (us) to tell those stories for them. It has led me to amazing work, and, lately, to a remarkable Chinese artist named Fan Ho, a visionary whose career spanned over seventy years, ending in 2016, and standing as a true chronicle on the evolution of China since the close of WWII. He was a street photographer long before such a term existed, developing an instinct for what Westerners called “the decisive moment” that elusive instant when all the narrative powers of an image are in perfect sync.

Born in Shanghai in 1931, Ho began snapping at an early age with a Kodak Brownie box camera, graduating to a Rolleiflex K4A, the camera that would be his career-long tool, when he was just fourteen. Developing his film in the family bathtub, Ho was almost completely self-taught, insisting that equipment and technique both took a back seat to emotion, and that he “didn’t work with any sense of purpose”. “I’ve always believed that any work of art should stem from genuine feelings and understandings”, he told an interviewer in 2014. “As an artist, I was only looking to express myself. I did it to share my feelings with the audience. I need to be touched emotionally to come up with meaningful works.”

By 1949, Ho’s family moved to Hong Kong, then beginning its rocket-sled ride into the fraternity of super cities, and experiencing unique growing pains and turmoil as it did so. Ho’s mastery of contrasting tones and shadows made for some of the most impactful black-and-white photography of the twentieth century, a magical balancing act between revealing and concealing. Beginning in 1956, his entry into exhibitions earned him over 280 international awards for excellence, and by the 1950’s, he segued into his second career in cinema, becoming a director a few years after and producing feature films until around 1980. Re-locating to San Jose, California in retirement, and encouraged by friends to return to still photography, he instead chose to curate his old negatives to gain access to shows in the United States, where many critics discovered the breadth and range of his output. At this writing, the easiest way to see even part of his work is in online image searches, as nearly all of his formally published collections are either out of print or seriously expensive…when they can be found.

I am one of many who wound up being late to the Fan Ho party, but a party’s still a party no matter when you arrive, and I am grateful for the chance to learn still another way to see, regardless of where the lesson originates. After all, the only real chance you have to learn anything is to admit how little you know.