FUNCTION OVER FORM

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY BEGAN MAINLY AS A MEANS TO DEPICT THINGS, to faithfully document and record. Those things tended to be fairly concrete and familiar; a landscape, a building, a locomotive, portraits, events. Later, when painting freed itself from such strictly defined subject matter, veering into ever more abstract and impressionistic areas, photography, too, found itself exploring patterns and angles that were less “about something”, tableaux that were interesting as pure form.

The industrial age created many installations and factories whose purpose was not clearly obvious at first glance, but as vast collections of pipes, ducts, platforms, and gear that, unlike commercial objects, didn’t at once reveal what their function was. They weren’t contained in stylish cabinets or hidden behind alluring packaging. They just were, and they just did. The arrival of abstract industrial photography was the perfect means for merely admiring the contour and texture of things, without the need for context or explanation. Edward Steichen, Walker Evans and other giants saw and exploited this potential.

That Day At The Plant, 2025

I find myself still drawn to the same aesthetic, as I enjoy walking into complex structures whose use is not immediately obvious. It’s not so much an attempt to imitate those earlier creators of pure form photography as it is to rediscover their joy in the doing. It’s an homage, but it’s also me trying to have a subject affect me in the same way it did for those who went before me. And, of course, with its refusal to use tone to explain or contextualize things, I prefer to do this work in black and white.

In the end, it’s just one more way to look at things, a way to shake up your expectations. You can’t surprise anyone else if you can’t surprise yourself. Forcing yourself to see in new ways, to reconfigure the rules for what a “picture” is, provides stimulation, and that, in turn, invites growth.

AIR THROUGH A REED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MERE HOURS AFTER MY NINETY-FOUR-YEAR-OLD FATHER and I shared a recent conversation on the creative process, I found myself staring at the computer screen in amazement. Both Dad and I have been photographers, musicians and writers over our lifetimes, and we have long marveled over the miracle of creation, and how it tends to happens not by us, but through us. The old metaphor of air whistling through a hollow reed to make music is not lost on us. We know that, when the muse is on us to any serious degree, it, not us, is in charge. And so, looking through my day’s shots a little after our conversation, I could not fail to be struck when I finally got around to reviewing this image:

I took this with about three seconds of forethought. The light, the color, the spareness of the composition, all coalesced very quickly, as did my belief that the entire inspiration had been my own. Following my talk with Dad, however, it struck me as merely my re-channeling of things I already “knew” from the work of other photographers, things that were operating on me far beyond the limits of mere influence. And, in looking at this random shot of a food truck at sunset, I searched my memory for what I believed to be the true genesis of the appeal of the shot. It didn’t take long.

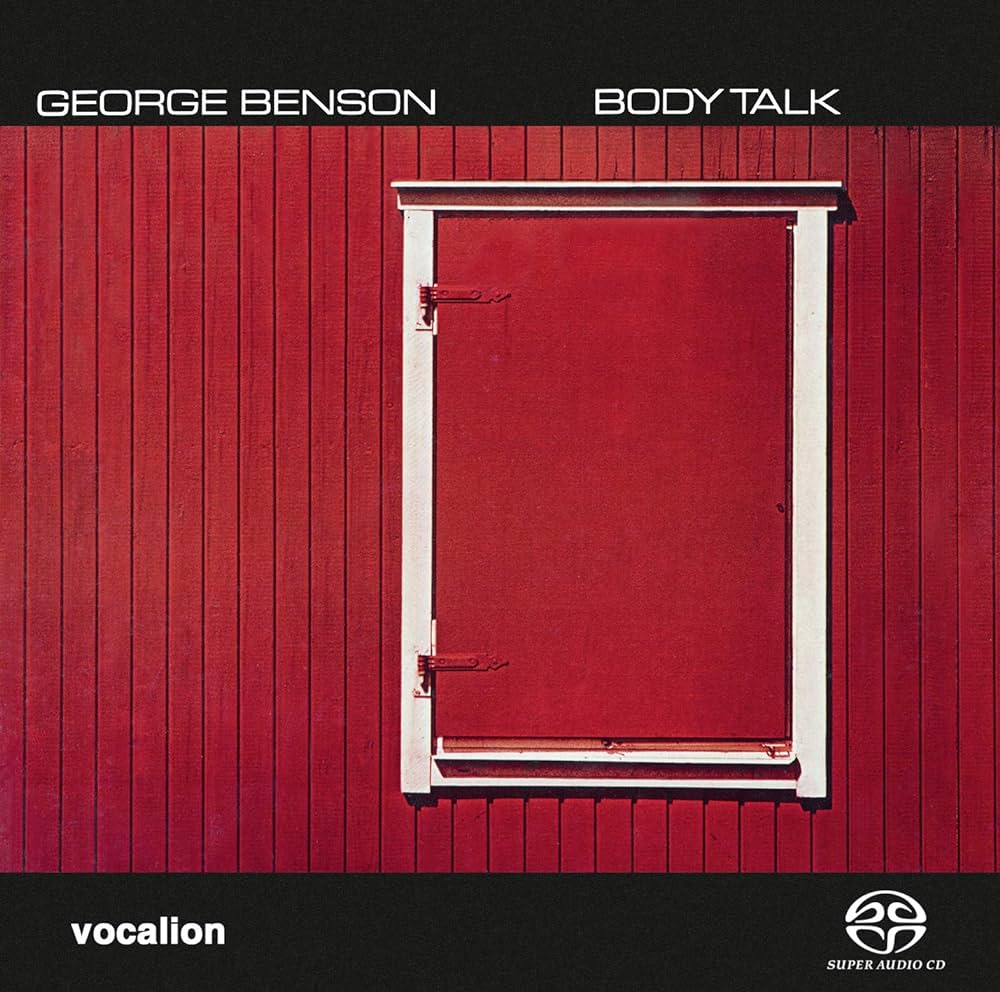

Pete Turner (1934-2017) was not, for the most part, a photographer who was commissioned to create album covers from scratch. In fact, many images from his existing body of work were often chosen by art directors at various record labels who just liked the pictures for their own sake. His photographs were not, then, “about” the featured artist or album title: they were just, as photographs, purely themselves. His cover here, for the George Benson album Body Talk, is typical, and, like many of the other covers I owned by him, it stunned me in its simplicity and directness. Years later (last week), I was not trying to “copy” Pete, nor create an homage to this shot; it simply bubbled up in some form in a way that was both unwilled and uncontrollable.

Photographers who fret too much about establishing their own “style” need not be dismayed when fragments of other artists come to the surface in their own work. No one can undertake the creative process without someone else’s hand on their shoulder. The trick is to celebrate what perhaps someone else has celebrated before you. The fact that you weren’t the first to enjoy smelling a rose does not make it smell less sweet. Let the air flow through you, and sing.

AT WAR WITH THE OBVIOUS

“I had this notion of what I called a democratic way of looking around, that nothing was more or less important. It quickly came to be that I grew interested in photographing whatever was there, wherever I happened to be. For any reason.” –William Eggleston

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MOST PHOTOGRAPHERS ARE NOT PRIME MOVERS, in that the majority of us don’t personally carve out the foundations of new truths, but rather build on the foundations laid by others. Art consists of both revolutionaries and disciples, and the latter group is always the larger. With that in mind, it’s more than enough for an individual shooter to establish a single beachhead that points the way for those who follow, and to be able to achieve two such breakthroughs is almost unheard of. Strangely, one of the photographers who did just that is, himself, also almost unheard of, at least outside of the intellectual elite.

William Eggleston (b. 1939) can correctly be credited as one of the major midwives of color photography at a time that it was still largely black and white’s unwanted stepchild. Great color work by others certainly preceded his own entry to the medium in 1965, but the limits of print technology, as well as a decidedly snobby bias toward monochrome by the world at large, slowed its adoption into artsy circle by decades. After modeling himself on the great b&w street shooters Robert Frank and Henri Cartier-Bresson, Eggleston practically stumbled into color, getting many of his first prints processed at ordinary drugstores rather than in his own darkroom. His accidental discovery of the dye-transfer color process on a lab’s price list sparked his curiosity, and he soon crossed over into brilliantly saturated transparencies, images bursting with radiant hues that were still a rarity even in major publications. Eggleston’s work was, suddenly, all about color. That was Revolution One.

Revolution Two emerged when he stopped worrying about whether his pictures were “about” anything else. Eggleston began what he later termed his “war with the obvious”, eschewing the popular practice of using photographs to document or comment. His portfolios began to center on mundane subjects or street situations which fell beneath the notice of most other shooters. The fact that something was in the world was, for Eggleston, enough to warrant having a picture made of it. A street sign, an abandoned tricycle, a blood-red enameled ceiling..anything and everything was suddenly worth his attention.

Reaction in the photographic world was decidedly mixed. While John Szarkowski, the adventurous director of photography at the New York Museum Of Modern Art, marveled at a talent he saw as “coming out of the blue”, making Eggleston only the second major color photographer to exhibit at MOMA, others called the work ugly, banal, meaningless. Even today, Eggleston’s subjects elicit reactions of “…so what??” from many viewers, as if someone told them the front end of a joke but omitted the punch line. “People always want to know when something was taken, where it was taken, and, God knows, why it was taken”, Eggleston remarked in one interview. “It gets really ridiculous. I mean, they’re right there, whatever they are.”

However, as can frequently happen in the long arc of photographic history, Eggleston’s work reverberates today in the images created by the Instantaneous Generation, the shoot-from-the-hip, instinctive shooters of the iPhone era who celebrate randomness and a certain hip detachment in their view of the world. As a consequence of Eggleston’s work, images have long since been freed of the prison of “relevance”, as people rightfully ask who is qualified to say what a picture is, or if there is any standard for photography at all. Thus does the obvious become a casualty of war.