THE WRITE SIDE OF HISTORY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE CAN BE NO BETTER DEMONSTRATION OF THE HUMAN RACE’S TWO CONFLICTING APPROACHES TO EXISTENCE than are on display in the peaceful town of Concord, Massachusetts, where one of the most renowned jumping-off sites for war and destruction sits cheek-by-jowl with one of the quietest monuments to the serenity of the mind. It’s a contrast which no photographer should fail to experience.

Just a few hundred yards from the tiny footbridge which is rumored to have launched the American Revolution is a carefully preserved haven known as the Old Manse, a modest two-story country home built in 1770 for patriot minister William Emerson. The home came, eventually, to temporarily host a trio of the young nation’s most eloquent voices: Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson (the good minister’s grand-son).

The house remained in the hands of the extended Emerson family until as late as 1939, when it was conveyed to the state’s Trustee of Reservations. Over the years, the Manse helped incubate the energies that produced Emerson’s Nature, Hawthorne’s Mosses From An Old Manse, and various love poems written between Thoreau and his wife. The house also retains writing desks used by Hawthorne and Emerson.

The manse supports itself, its side garden and its replica corn field with a modest bookstore and daily walking tours of the house’s rooms, which are said to feature nearly 90% of the structure’s original furnishings. However, as is the case with Annie Liebowitz’ profound essay on the living spaces of quintessential Americans, Pilgrimage, the effect of the house on the photographer’s eye can never only be in the arrangement of physical artifacts. There is something more ethereal going on than merely snapping The Place Where He Sat And Wrote, an unfilled space that exists between these mere things and the essence of those transcendent writers.

And while I’m not sentimental enough to believe that you can render a person just by photographing an object from his desk, there is something that lingers, however impossible it is to quantify. Revolutions are very amorphous things. Some come delivered by musket ball. Others arrive in wisps of quietude, seeping into the soul with the stealth of smoke. The Old Manse launched its own crop of “shots heard ’round the world”, the echoes of which can sometimes resound in the echo of an image.

It’s a lucky thing to be ready when the message comes.

WHERE THE RUBBER MEETS THE ROAD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY WIFE AND I HAVE REACHED A REASONABLE DIVISION OF LABOR as regards road trips, with her taking on the nation’s freeways like an original cast member of The Road Warrior and me decoding various navigational vectors, from AAA maps to iPhones, as well as uber-producing the in-car tune mix. Everybody to their strengths and all that. This arrangement also frees me up to pursue the mythical goal of Immortal Photograph I Shot Out A Car Window, which will also be the title of my Pulitzer Prize acceptance speech.

Any day now.

Most of these potential world-beater images have been attempted through the front windshield, where it is at least a little easier to control blur, even glass reflection. Additionally, the majority of them, more and more, are done on mobile phones, which is not the greatest for resolution, but gives you that nice exaggeration on dimensions and depth that comes with a default wide-angle lens, which, in some cases, shoots broader vistas than even the kit lens on your “real” camera.

If you find yourself doing the same thing, you have no doubt noticed that you must get really, really close to your subject before even mountains look like molehills, as the lens dramatically stretches the front-to-back distances. You might also practice a bit to avoid having 10,000 shots that feature your dashboard and that somewhat embarassing Deadhead sticker you slapped on the windshield in 1985.

So, to recap: Shoot looking forward. Use a mobile for that nice cheap arty widescreen look. Frame so your dash-mounted hula girl is not included in your vistas (okay, she does set off that volcano nicely..). And wait until you’re almost on top of (or directly underneath) the object of your affection.

And keep an ear out for important travel inquries from your partner, such as: “are you gonna play this entire Smiths CD?”

Sorry, my dear. Joan Baez coming right up.

THE GENESIS OF REAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

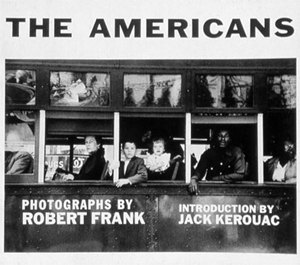

“(the book is) flawed by meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposure, drunken horizons, and general sloppiness, (showing) a contempt for quality and technique…” –Popular Photography, in its 1958 review of The Americans

THOSE WORDS OF DISDAIN, designed to consign its subject to the ash heap of history, are now forever attached to the photographic work that, instead of vanishing in disgrace, almost single-handedly re-invented the way the world saw itself through the eye of a camera. For to thumb through Robert Frank’s 1958 collection of road images, The Americans, is to have one’s sense of what is visually important transformed. Forever.

THOSE WORDS OF DISDAIN, designed to consign its subject to the ash heap of history, are now forever attached to the photographic work that, instead of vanishing in disgrace, almost single-handedly re-invented the way the world saw itself through the eye of a camera. For to thumb through Robert Frank’s 1958 collection of road images, The Americans, is to have one’s sense of what is visually important transformed. Forever.

In the mid-1950’s, mass-market photojournalist magazines from Life to Look regularly ran “essays” of images that were arranged and edited to illustrate story text, resulting in features that told readers what to see, which sequence to see it in, and what conclusions to draw from the experience. Editors assiduously guided contract photographers in what shots were required for such assignments, and they had final say on how those pictures were to be presented. Robert Frank, born in 1924 in Switzerland, had, by mid-century, already toiled in these formal gardens at mags that included Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, and was ready for something else, a something else where instinct took preference over niceties of technique that dominated even fine-art photography.

Making off for months alone in a 1950 Ford and armed only with a 35mm Leica and a modest Guggenheim grant, Frank drove across much of the United States shooting whenever and wherever the spirit moved him. He worked quickly, intrusively, and without regard for the ettiquette of formal photography, showing people, places, and entire sub-cultures that much of the country had either marginalized or forgotten. He wasn’t polite about it. He didn’t ask people to say cheese. He shot through the windshield, directly into streetlights. He didn’t worry about level horizons, under-or-over exposure, the limits of light, or even focal sharpness, so much as he obsessed about capturing crucial moments, unguarded seconds in which beauty, ugliness, importance and banality all collided in a single second. Not even the saintly photojournalists of the New Deal, with their grim portraits of Dust Bowl refugees, had ever captured anything this immediate, this raw.

Frank escaped a baker’s dozen of angry confrontations with his reluctant subjects, even spending a few hours in local jails as he clicked his way across the country. The terms of engagement were not friendly. If America at large didn’t want to see his stories, his targets were equally reluctant to be bugs under Frank’s microscope. When it was all finished, the book found a home with the outlaw publishers at Grove Press, the scrappy upstart that had first published many of the emerging poets of the Beat movement. The traditional photographic world reacted either with a dismissive yawn or a snarling sneer. This wasn’t photography: this was some kind of amateurish assault on form and decency. Sales-wise, The Americans sank like a stone.

Around the edges of the photo colony, however, were fierce apostles of what Frank had seen, along with a slowly growing recognition that he had made a new kind of art emerge from the wreckage of a rapidly vanishing formalism. One of the earliest converts was the King of the Beats Himself, no less than Jack Kerouac, who, in the book’s introduction said Frank had “sucked a sad poem right out of America and onto film.”

Today, when asked about influences, I unhesitatingly recommend The Americans as an essential experience for anyone trying to train himself to see, or report upon, the human condition. Because photography isn’t merely about order, or narration, or even truth. It’s about constantly changing, and re-charging, the conversation. Robert Frank set the modern tone for that conversation, even if he first had to render us all speechless.

ANTHROPOGRAPHY

Tuning up: a fiddler runs a few practice riffs before a barn dance in Flagstaff, Arizona.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WRITING CLICHE NUMBER 5,218 STATES THAT YOU SHOULD WRITE about what you know. Mine your own experience. Use your memories and dreams as a kickoff point for the Great American Novel, or, at least, the Okay American E-book. But while the “know-it-do-it” school of technique offers writers a pretty sound foundation for scribblers, photographers need to learn how to leave their native nests and fly into unknown country. The best pictures sometimes are where you, comfortably, aren’t.

Caperin’ up a storm, by golly.

Shooting an event or lifestyle that is completely outside yourself confers an instantaneous objectivity of sorts to your pictures, since you don’t have any direct experience with the things you’re trying to capture. You’re forced to pretty much go instinctive, since you can’t draw on your memory banks. This is certainly true of combat photographers or people dropped down into the middle of fresh disasters, but it also works with anything that’s new to you.

Take square-dancing. No, I mean it. You take square-dancing, as in, I’d rather be covered in honey and hornets than try to master something that defines “socially awkward” for yours truly. I can’t deny that, on the few occasions that I’ve observed this ritual up close, it obviously holds infinite enjoyment for anyone who isn’t, well, me. But being me is the essential problem. I not only possess the requisite two left feet, I am lucky, on some occasions to even be ambulatory if the agenda calls for anything but a rote sequence of left-right-left. Again, I concede that square-dancers seem almost superhumanly happy whenever doing their do-si-doing, and all props to them. Personally, however, I can cause a lot less damage and humiliation for all concerned if I bring a camera to the dance instead of a partner.

Shooting something you don’t particularly fancy yourself is actually something of an advantage for a photographer. It allows you to just dissect the activity’s elements, using the storytelling techniques you do know to show how the whole thing works. You’re using the camera to blow apart an engine and see its working parts independently from each other.

In either writing or shooting, clinging to what you know will keep your approach and your outcomes fairly predictable. But when photography meets anthropology, you can inch toward a little personal growth. You may even say “yes” when someone asks you if you care to dance.

Or you could just continue to maintain your death grip on your camera.

Yeah, let’s go with that.

Share this:

September 25, 2015 | Categories: Americana, Black & White, Candid, Conception, iPhone, Musical Instruments | Tags: Composition, crowds, Entertainment, Music, social commentary | Leave a comment