QUIET CONVERSATION

“I am sort of a spy..”—-Vivian Maier

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS AN IRISH STREET PHOTOGRAPHER that I occasionally see on a favorite photo-sharing site that may be the most unabashed eavesdropper I’ver ever encountered. He only shoots with a telephoto, always from a very long and safe distance, and his entire output consists of unposed candids of passersby. He finds them in shoppes, at fairs and markets, waiting on buses, whatever. The images usually show the complete upper bodies of his subjects, but often they are merely headshots. His passion is the unguarded moment, the sudden revelation of humanity when the mask of civilization slips a tad. In this he is not unique; many street shooters focus on such studies. However, it is nearly 100% of his output, and, since he posts so frequently, the viewer is liable to witness many hits among his misses.

Now, I leave it to you to discern the ethics of merely spying on passersby in pursuit of some kind of enlightenment. I myself give in to the urge now and then (as seen here), and I regularly argue whether this qualifies me as investigator or sneak-thief. Perhaps a bit of both. Shooting on the fly while a human interaction is ongoing certainly records the complete gamut of emotion, and that in itself can be hypnotic. But why? Is our understanding of our own secret selves somehow enhanced by looking over the shoulder of others’ lives? There have been enough debates about this one aspect of street work to fill up the Library of Congress.

Sometimes it’s a single shot that seems revelatory. Other times, as seen here, a sequence of shots may have a certain allure. Shooting in burst mode can be a bit like making a very short movie and viewing it a frame at a time on a film editor, like the ancient Movieola editors. And then there is the question every photographer must answer. Is more really more, and, if so, more of what? I find I tire when a shooter’s work is totally composed of random candids. I would feel either stuck or lazy or both if that was all I shot, but everyone to their own style. I do recognize that other people’s lives are occasionally fascinating, but I have still to explain why that is.

PULLING BACK FROM THE REAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE GREATEST LEGACIES of the first two hundred years of photography has been the ability of images to be either anchored to, or completely thrown clear of, the literal world. Pictures may have been originally made to document, or prove, or demonstrate elements of reality, to preserve time in ways previously impossible. However, they soon revealed the photographer’s urge to interpret, not merely set things down on salted paper. This was the creative instinct, the demand of the individual to see life in distinctive and unique ways, commenting, rather than merely cataloging.

There has never been a better time to be a photographer. Never.

Phantom Squadron, 2024

This is not because of any one technical development or scientific breakthrough. It’s because the accumulated power of the billions of images made every day has removed the last few barriers to photography as an art. Given the flood tide of choices we enjoy at present, we can’t even agree on what constitutes a “camera” anymore. Devices don’t matter except that they sometime free us in other ways, like allowing us to shoot anything, anywhere, and make it look like whatever we want. Even without the influence of A.I., which like any development, will either be a miracle or a curse, depending on the user, we are already virtually unhindered in being able to technically render any kind of image we can imagine. Our eyes must be master of our tools, to be sure, but there is no longer any limit on what those tools can be.

All of which begs the question, why does it matter whether we reveal how we created a given shot? One, the only thing that really matters is the result, and nothing about a strong picture can be made any stronger by explaining that it was made by using X and Y to accomplish Z (so throw away the captions on 99% of the pictures hanging on museum walls). Two, even if we share the absolute step-by-step “recipes” on how a given shot was made, the execution of that recipe will still vary from artist to artist. We simply can’t create a uniform version of either reality or unreality. Which is to say, as we always do in these pages, feel more than you think. Convey rather than record. Always be shooting, and always ask yourself about how much of you makes it into the final picture. What else is there?

AS LOUD AS A WHISPER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GRAPHIC ARTIST CHARLEY HARPER was dead and buried some twenty years or more before his balletic interpretations of the natural world were “discovered”, even though, during his lifetime, his commercial work was published in the world’s most popular magazines and generations of school kids viewed the illustrations he created for their nature and science books. What happened to make Charley a newly “found” treasure was twofold: first, over a lifetime, he steadily streamlined and simplified his style to convey animals, insects and the elements in fewer and fewer lines, constantly learning how to put an idea across without excess ornamentation; and secondly, and perhaps equally important, his audience, which had always accepted Charley’s eye as a natural way of seeing the world, came to realize just how difficult it was for him to make it all look so effortless.

Photography, never a final product but a lifetime process, works the same way. The first versions of our visions can be cluttered, busy, an audition for attention (or “likes”, if you prefer) as the artist struggles for acceptance. We tend to throw everything into the soup. We initially regard words like “minimalism” with suspicion, as if the work done under that term is somehow incomplete. However, if we are lucky, we come to see mere compiling of detail as occasionally unnecessary for the task at hand, which is to convey an idea.

I don’t always have the discipline to shoot with the bare essentials in mind. I defer to sharpness; I become fixated not with the bridge but with the billion bolts holding the bridge together. Pulling stuff out, doing more with less, is never instinctual to me. If I were a small child making a drawing of a sunset, such as the one seen here, I would likely make it about simple shapes, basic colors and a direct message. Unfortunately, I grew into an adult and started gilding the lily. In terms of writing, same same. This blog tends to bloat in its first drafts, whereas the posts I re-write the most somehow become shorter and clearer. In viewing our images, especially those from earlier versions of ourselves, it’s worth asking whether we could have upped our impact by turning down the distractions.

Sometimes we use our cameras to shout. Sometimes, a whisper will suffice. Charley Harper knew that he was in a partnership, a conversation, with his audience. He was thus free to use his simplified style as an opening remark, waiting for others to jump in and supply the rest of the thought. When we conform that kind of relationship with our photographs, connections with our viewers become truer.

Stronger.

THE PHANTOM MENACE

Eagles with the jitters: jagged lines and poor definition from “heat shimmer”.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

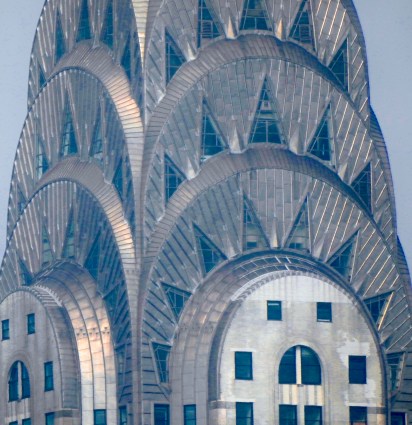

CATCHING THE PERFECT GLIMPSE OF A SKYSCRAPER is more luck than craft, and, in a city like New York (okay, there is no city like New York), you have a million different vantage points from which to view a sliver or slice of buildings that are too generally immense to be captured in their entirety. You pick your time and your battle.

One of the short cuts to the perfect view of these titans is, of course, a telephoto lens. I mean, what could be easier? Zoom, focus, shoot. Except that, with very long lenses, even the most sophisticated ones, things happen to light that are very different from how illumination works at close quarters. One problem for zoomers is the dreaded “heat shimmer”, the thermal layers that occur in between camera and far-away subject, warping straight lines and turning fine detail into mush. Sharpness in zoom shots can suffer because heat waves, which can vary widely depending on prevailing weather conditions, are bending the light and confusing your camera’s auto-focus system. The tight shot of the eagle gargoyles at the 61st floor of the Chrysler building, seen up top here, is a good example. They resemble a charcoal sketch more than they do a photograph. This image was shot from about a 1/4 mile away on the banks of an inlet bay near Greenpoint, Brooklyn, looking across at the Manhattan skyline. It was taken on a Nikon Coolpix P900, one of the brand’s so-called “superzooms”, allowing me to crank out to about 2000mm.

Still an imperfect shot, but snapped at the same focal length with somewhat straighter results. Wha?

And yet, consider the other shot, also of the upper floors of the Chrysler, and also shot at 2000mm just minutes away from the gargoyle image. Lines are generally solid and straight, even though shot from just about the same distance. Here’s where we get to the key word “variable”. Everything I shot in this batch was in the early morning, and so the sun was actively burning off a light overcast, which, I assume, made for shifting air temperatures in nearly everything I photographed. The P900’s small sensor, which is what happens when your put too many glass elements in a compact lens, pretty much shoots contrast to hell at long distances, as you can see in both shots, and responds to anything other than direct light with zooms that are, to be kind, soft. Still, being mindful of heat shimmer as a real factor in your telephoto work can sometimes result in pictures that, while far from perfect, are technically acceptable. The phantom menace can’t be eradicated, but it can be tamed.

TWO-WAY MIRROR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GLASS IS BOTH A REVEALER AND CONCEALER in photography, acting in equal amounts as truth-teller and liar. Light neither bounces perfectly off a glass surface nor permits 100% transparency, and so individual shooters have to strike an arbitrary and individual balance between seeing into and seeing onto. This artistic see-saw is one of the most intriguing calculations anyone can make with a camera.

Even if it were possible, optically, say, for a window on a building to allow us to only see in or only see reflections of what is behind the camera, the mixture of see-in/see-on would still be very seductive. The pioneering French photographer Eugene Atget, in documenting shop windows around Paris in the 1800’s, was also documenting the texture of street life in the city as it was reflected in those windows. And over the subsequent centuries, what a certain type of viewer might see as an error went on to become a standard form of commentary by succeeding generations of photographers, from Garry Winogrand to Robert Frank to Walker Evans and beyond. Certainly, this idea that a window is both portal and mirror caught on so universally that it has become something of an urban cliche. But, of course, things become cliches at first because they are undeniably true.

Just as Jerry Seinfeld once said that “men aren’t interesting in what’s on TV; they’re interested in what else is on TV”, I’m never interested in just looking in or out of a window. Noticing, and exposing for, and composing for, what else is impacting that window keeps me interested. If nothing else, showing the world beyond the glass plane, even when reversed and distorted, contextualizes the story that a peek through a window only begins. For me, it’s like imagining a really strong beginning sentence, and then realizing that, based on where I place punctuation or accent marks, I can steer that sentence to deeper meaning. Clear as glass.

HURT TIL IT SMILES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WILDLIFE HAS BEEN SUCH A SMALL SUBSET of my overall photographic work over a lifetime that it holds a very special challenge for me. In shooting nearly everything else, I have landed at what might be termed a plateau of competence, an ability, through repetition and practice, to predictably deliver a decent result in a variety of disciplines. However, immersing myself in nature subjects places me so far outside my comfort zone, so far from any smug illusions of mastery, that it involves real risk. Ironically, more than ever before, that is where I am deliberately placing myself. Art doesn’t always thrive in the danger zone, but, on the other hand, doing what you’ve always done means you’ll always get what you’ve always gotten.

Green heron perched on a boat. Best to take the freebie and relax, but….(see next)

Bird work is a subset inside a subset, occupying a larger portion of my nature output in recent years, and offering equal portions of satisfaction and frustration. Birds are unlike other subjects for portrait work because they don’t care what I want and aren’t here to make me a success at it. They exist in their own sphere and under their own impulses and needs, and whether I can focus fast enough to catch them on the wing, or compose well enough to properly showcase them is of no importance to them. I am, by habit, caught up in what I want to achieve or capture, or, technically, succeed at. To properly photograph a bird, you have to shift every normal emphasis of style and approach. You can’t go out with a given quota or “yield” in mind, as conditions shift so quickly, so consistently that, on many days, you’re fortunate to have even a single usable shot to show for your effort. But that’s not really a negative. In fact, quite the opposite.

…Mr. Heron decides he’s out of here, and you’re too slow, boyo. In otherwords, a typical day.

To, as portrait photographers used to term it, “watch the birdie”, you have to develop a different kind of watching than for any other form of photography. You have to slow down. You have to listen as well as see. And you need to silence the part of your ego that instinctively thinks of the photograph as a trophy, as one more scalp on your belt. It sounds very New Age-y to say that you need to “let the picture take you”, but that is, at least, an approximation of what you’re aspiring to. Finally, given the sheer number of blown shots you must walk past on the way to the keepers, you need to be all right with failure, or at least be able to find a new definition of “success”. Art is not something that’s logged on a scorecard; it’s peeling away all the wrong versions of something until the right version is revealed. You hurt ’til you smile. Nature work is its own separate discipline, in that it’s defined by how well you manage yourself, rather than whether you tame the subject.

UM, THANKS, I GUESS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO ARE EVEN MINIMALLY HONEST WITH THEMSELVES learn early on how to own their mistakes, to admit that sadly, such-and-such a picture just did not work out. Even if they are slow in learning this, they will no doubt be forced to answer the question “what happened here?” from other photographers. This acts as a double-strength multiplier for humility. Good photos speak softly in praise of their creators. Bad photos wear loud colors and walk around with a bulls-eye on their behinds.

The one chance a shooter has to pass off a poor shot is if the result, however comprised in his own estimation, actually manages to “speak” to someone else. All it takes to break us out of a sell-pitying sulk is for someone, anyone to ask, “oh, how did you do that?”, allowing us to glibly remark along the lines of “oh, you see what I was up to, did you?” or “yes, that’s what I was going for all along..” In such cases, it’s forgivable to just take the win, rather than answer the viewer with “are you nuts? This pictures stinks!”

Sunrise Over Bard Lake, Simi Valley, near Thousand Oak, California, 2/3/25

I recently had positive reaction to such a shot, a picture that I had already rejected as close, but no cigar, a landscape that you see here. It was the result of an early dawn enveloped in bright hazy glare combined with a superzoom, needed for the bird walk I was starting, but which, due to its tiny sensor, was guaranteed to render details mushier the farther in I cranked on my subject. And so you see a very soft, muted rendering of all the tones, resolving into a look that photogs have come to term “painterly”, which is French for “not as sharp as I’d hoped for”. Still, several people had given me oohs and aahs on it, so it was very tough to tell them they didn’t know what they were talking about. The scene is, after all, very dreamy, and might still have been on the mushy side even with a more sophisticated camera. The aggravating thing for me is when a picture works for everybody else but me. Makes me wonder how many art museums are brimful of works their creators regard as flawed. I’m sure the math on such a study would be surprising.

In the meantime, thanks, I reply, adding, as a post script, you oughta see what happens when I actually know what I’m doing. The P.S., of course, is silent. And it damned well is going to stay that way.

COOLNESS IS NOT CREATIVITY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OKAY, ENOUGH OF THIS.

As analog photography has, in the twenty-first century, fallen out of ubiquitous use, there has been a mounting wave of nostalgia for the hands-on nature of film-based technology. In some cases, that yearning has actually revived some niche sub-worlds of old, such as in the rebirth of instant cameras. There has also been the “lomography” and Lensbaby movements that sparked a renewed interest in the visual artifacts of (mostly cheap) film cameras, the ones that leaked light, over-saturated or mangled colors, or sported plastic lenses instead of glass, all in pursuit of the “unpredictability” or “authenticity” of pictures over which you have less control. Blur? Hey, that’s an artistic choice! Double-exposures? Why, they’re spontaneous and random! This entire trend, which results in sales for a fairly large market of hipster-driven products, has proven particularly attractive to people who find digital imaging a cold, idiot-proofed process that has been drained of all of its humanity.

But the sterility that some digital photography can be said to possess isn’t in the technology, and neither is the warm magic falsely attributed to analog. Last year, Flickr, arguably the world’s biggest photo-sharing community, saw work posted to its site from shooters using over seven thousand different kinds of captures devices, devices that ranged from standard point-and-shoots to medical sensors to things that created pictures with sound, or heat, or….you get the idea. The fact is, nearly anything can record, refract and interpret light patterns. It’s not the product that delivers a cold experience. It’s the user. Analog photography has received too much credit of late for being more “genuine”, more connected to the human soul, than other methods, and that, as they say in Holy Scripture, is just a load of crap.

We would never allow writers to bully each other about which pencil or notebook yielded better prose or poetry: it likewise would be ludicrous to say a song was less rhapsodic depending on whether it was delivered to the listener with a pair of drugstore earbuds or a Bose 791 Series II ceiling speaker. And it’s frustratingly stupid for us to argue about what device captures the picture. Because a human heart, a human eye needs to be behind that device, enabling it, controlling it, or there simply is no picture. There are no shortcuts, no foolproof recipes, for making compelling images. There is only the work, the real, tough, slow sweat in search of mastery of one’s self. Once that mastery manifests itself, any camera will yield miracles. Without it, all gear is junk.

360 DEGREES OF SPECULATION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A good photograph is knowing where to stand.

ANSEL ADAMS MAY WELL HAVE HAD HIS TONGUE FIRMLY IN HIS CHEEK when he made that famous remark, given that he devoted his life to all of the technical mastery of photography that lay well beyond the mere skill of composition. However, many of us following in his footsteps adopted the sentence as Holy Writ, governing our very sense of how to capture a scene, based on where you choose to see it from.

One of the reasons I love to work in museums so much is that the quiet and measured pace of reality within their walls. It makes even the most fevered brain hit the brakes, slowing our roll to the point where tiny things that might not reveal themselves out on the street spring up out of the shadows and whispers. This serves me well when trying to deal with a ton of brand new visual information, and, in turn, trying to answer the question “what do we make of this?”

The three shots you see here, all of the entrance foyer to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, were taken over the space of an hour and a half, under slightly different lighting conditions and with a slight variance in exposure and color strategy. Each one presents an opportunity for a narrative, but trying to select a so-called “best” shot among them is really irrelevant. What’s important is that slowing my process, taking time to digest the subject matter, resulted in several distinctly different takes on the same scene. That means options, choices, and a kind of photography that is the polar opposite of a snapshot.

Of course, some pictures do actually spring fully-born out of the moment, and they need to be respected for the miracles that they are. Other images build slowly. You turn your airplane around and take one more pass over the field, and then another, and another. It’s that fear that “I may not really have it yet” that makes it likelier that you eventually will get it, or at least get something deliberate, something considered. Going for just one more take is particularly valuable when you’re shooting something that has been shot to death, like an international landmark. Nailing the expected postcard shot can be gratified, but it’s always valuable to hear Uncle Ansel’s voice in your head, and asking yourself if there’s a better, different place to stand.

SUM OF ITS PARTS

I’ve just seen a face / I can’t forget the time or place where we just met / she’s just the girl for me / and I want all the world to see we’ve met……. John Lennon/ Paul McCartney

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN IT COMES TO STREET PHOTOGRAPHY, there is a reason that we use the phrase “a face in the crowd” rather than “the face in the crowd”, because, just as there is no single solution to the challenge, “go shoot a sunset” there can be no one face that satisfies the desires of every photographer. The combination of features, textures and expressions that compose the human visage come together in billions of combinations, some of which will entice and enthrall us, others that will repel us, and yet others that may not register at all. The human face is one of the grand, miraculous intangibles of visual art, which is why, centuries after old man Da Vinci laid down his brushes, we still can’t agree if the Mona Lisa is coquettish, innocent, wise, or a dozen other states of mind. And that’s great news for picture-making.

If I were to be assigned an essay to try to explain why the face of this young woman spoke to me on a certain day and a certain place, I would get an “F” or at least an “incomplete”. How can you quantify any of this? The face’s appeal can’t be reduced to mere physical beauty, since that phrase, in itself, produces no general consensus. Terms like plain, homely, comely, intriguing are likewise useless in describing what makes a photographer, or a novelist or a painter or a songwriter, for that matter, want to glorify a particular person. And then, beyond that, as Lennon & McCartney put it so well, there’s the random circumstances behind the discovery of the face:

Had it been another day / I might have looked the other way

And I’d have never been aware / But as it is I’ll dream of her tonight…

There are many, many things captured in an image that have no objective reason to be there, but the human face might just be the one thing that absolutely confounds any attempt to answer the question, “but why that one?” Some mysteries are impenetrable, and, wondrously, should be allowed to remain so. The truth is simple: I’ve just seen a face.

SUPER STAND-INS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Los Angeles’ E.Clem Wilson building, the first structure to portray the Daily Planet on film.

SINCE ITS VERY BEGINNINGS, THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY has made bank by creating and marketing alternative realities, visions of what they hope we’ll believe, at least until the last frame of film clears the projector gate. So lasting are some of these illusions that they become more authentic than the actual in-life objects or locations that were used to generate them.

In my own case, one of the first and most influential times a thing from the “real” world was re-purposed to stand for something else was in my daily viewing of reruns of The Adventures Of Superman, in which exteriors of various Los Angeles landmarks were substituted for key locations in the Man Of Steel’s fictional world. Of course, at the age of seven, I tended to take everything Hollywood presented to me at absolute face value; if the storytellers told me a thing was so, that was it, as far as I was concerned. So of course, when I saw a shot of the E. Clem Wilson building (in the earliest episodes of the show) or the Los Angeles City Hall (for the later stories), I knew that actually, they were the headquarters of the Daily Planet, the hallowed shrine of journalism in which Clark and Lois and Jimmy clacked away at Royal typewriters in pursuit of The Next Big Scoop.

Los Angeles City Hall, which followed the Wilson building as the second version of the Planet on the Adventures Of Superman TV series.

Of course, as a lad, I I knew nothing of the film industry’s century-long habit of saving a buck by using stock shots to stand in for something that they didn’t want to build from scratch. I saw exactly what they wanted me to see, and thought about it exactly how they wanted me to think. At that age, I certainly didn’t have any sense that film-makers, just like propagandists or documentarians, could make me look at an image and draw associations from it that had no root in fact. A few years later, as I stumbled into photography, I developed my own ideas on how to idealize the things I shot. Being a total noob, I thought everything I pointed my camera at was important, or beautiful, because that’s what the process of making a picture felt like to me. Years later, when I looked at my earliest “good” pictures, I was amazed at how truly horrible many of them were, and how, in my my mind’s eye, I had wildly over-inflated their value. Eye of the beholder and all that.

At this writing, in early 2025, yet another cinematic reboot of the Superman myth is being readied for the screen, and yet another visual symbol of the Planet building will be needed for the present generation. However, unlike the producers of Adventures Of Superman, who were bringing in every episode of the show at a rock-bottom budget of about $15,000, the new crew won’t have to settle for just shooting some random place and merely renaming it. CGI and other tools will make literally anything possible. And yet I still find myself going back to the L.A. City Hall, where, somewhere in one of the Planet’s vast corridors, there is that miraculous storage room into which Clark Kent disappears to become The World’s Mightiest Mortal. For my inner seven-year-old, you can’t get any more “real” than that. And that’s the superpower of photography. Superman may be able to bend steel in his bare hands, but a picture can twist reality to any purpose.

USER-FRIENDLY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WORLD’S MOST TITANIC ATTRACTIONS, either natural or man-made, are almost always depicted from a distance, adorning postcards, brochures or posters from some ideal perch that allows the camera to take in the entire spectacle of The Very Special Thing within a single frame. That’s the way a tourist sees things like the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, or the Grand Canyon; the way they appear in the promotional photograph, the souvenir. For those locals who pass by or through those places daily at street level, however, the view is often very different, in that the part (the thing that I use) varies significantly from the whole (the thing the visitors visit). And that, in turn, provides the best way to see something ultra-familiar in a whole new way.

Example: seen as merely a single feature in a vast panorama that includes both the Brooklyn and Manhattan sides of the East River, the George Washington Bridge looks like a single, continuous flow of metal and macadam, when, in fact, it is a gigantic jigsaw puzzle of millions of interdependent parts…rivets, supports, struts, platforms, staircases, arches…a colossal collaboration of assemblies and sub-assembles. And, in photographic terms, forcing the eye to take in just a subsection of it, as seen here, forces the mind to take the familiar in as a totally unfamiliar thing, allowing for photographs that render an accepted form in a novel manner. It is, in effect, the anti-postcard view…a re-engagement of the senses with something long thought to be complete known.

Cities that attract tourists contain certain visual cues for the visiting photographer, or the urge to capture the super-familiar, to get “the” shot of certain locales. It’s almost as if snapping the expected photo of the Very Special Thing ticks off a box on a list of assignments. But homework and creativity don’t work well together. Struggling to find one’s one version of the super-familiar promotes growth, and, for the viewer, actually broadens our comprehension of that thing. “Nothing new under the sun”, goes the saying, but no one who calls him/herself a photographer can ever accept that proposition. Turn the corner, flip the angle, change the outcome.

“SAME DAY” BLUES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT WAS JUST A HEARTBEAT AGO that I posted an appreciation of the current generation’s crop of camera sensors, trumpeting proudly how much easier it has become to capture high-resolution images, hand-held and on the fly, in greatly compromised lighting situations. I went on at some length (as I do) about how noise reduction, coupled with greatly expanded ISO ranges, had made it possible to salvage images that, just a generation ago, would have been lost, and I posted a shot taken within an extremely dark museum gallery that demonstrated my point.

Then I remembered this picture:

Same day, same inky black museum interior, nearly the same technical specs. To refresh, I was shooting that day on a Nikon Z5 full-frame mirrorless (so, a pretty recent camera) with a fully-manual, 24mm F-mount Nikon lens from the 1970’s. It’s attached to the body via a generic F to Z adaptor, so no information flows between the glass and the rest of the camera. The picture was taken wide open at f/2.8, just like most of my other shots for the day, and just like the humble-brag shot I posted several weeks ago from the same museum tour, which was remarkably noise-free and fairly sharp. Similarly, both shots were taken at 5,000 ISO.

So why is this take so much softer and…I dunno, smudgier? Well, that’s the kind of “what happened?” question that keeps one up at night. Lessee, there may actually have been less light to work with than in the first shot that I was so happy with. I could have mis-dialed the manual focus. Have I mentioned the possibility of gremlins or unclean spirits, i.e., a ghost in the machine? Meh. I can excuse the shot due to its general feel and composition, and perhaps pass it off as “painterly” which is a voguish catch-all alibi that loosely translates to “I screwed up but perhaps I can make you believe I did it with some higher purpose in mind”. Ah, well, as they say at Bowlero, set ’em up again in the next alley. Maybe next time I can make the 7-10 split….

LOST AND FOUND

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THIS PLATFORM WAS NEVER ABOUT MERE GEAR OR TECHNIQUE. Looking at the blogosphere of a dozen years ago, I decided that it was saturated with how-to’s and equipment reviews, things that I had found had less and less to do with how I was actually trying to make pictures. And so, from the start, The Normal Eye has been about intentionality. What was I trying to do? How close did I come? What was in me that had to change to make images “work” better? And what could I learn that might be helpful to others like myself?

One of the by-products of all this is that it’s taught me to look, photographically, for evidence of other people’s intentionality; to try to chronicle their magical transformation between thinking about a thing and becoming that thing. Take as an example the young dancer seen here, who began her improvised dance in the surf by randomly frolicking down the beach for a photographer friend. I happened upon the scene from afar, using a telephoto to maintain a healthy distance from the pair so as not to interfere with their process. And then I saw something wondrous.

Within a few seconds, the young woman went from letting a thing happen to her to trying, intentionally, to control and direct it. She went from participating to creating. She tore herself loose from the state of being “found” in something planned, to becoming blissfully “lost” in something of her own making. Whatever “this” was, it was no longer a series of poses. Now, it was a dance.

In a moment, I was reminded of what I had been seeking, millions of photographs ago, when I began all this. This blog’s name is subtitled with the word “journey” for a reason. I was learning, day by day, how to trust my own instincts beyond the mere technical mastery of a craft, dancing as intentionally as I could toward the edge of art. Sometimes, it still feels like I am just alone on a beach, twirling around aimlessly. But, in some miraculous moments, my footwork changes. I can hear a rhythm. I leave behind the “found” world and find myself giddily “lost”

And then I can dance.

THE ILLUSION OF AN ILLUSION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOS ANGELES’ ACADEMY MUSEUM OF MOTION PICTURES is, in a town veritably built upon buzz, one thing that more than lives up to the hype, a dazzling treasure house that celebrates the entire history of Hollywood magic-making. Packed with exactly what you’d expect from a century of trophy hoarding by the same folks who brought you the Oscars, the Academy Museum is the place where you go to catch an up-close encounter with Dorothy’s ruby slippers or Charles Foster Kane’s sled. But as amazing as the permanent collection at the AMMP is, the special exhibitions are even more astonishing.

An offer you can’t refuse, at least with a digital camera: f/4, 28mm, ISO 3200, 1/30sec, handheld.

One of the museum’s key attractions from 2024, ending early in 2025, is an entire wing honoring the 50th anniversary of the release of “The Godfather”. Some of the exhibits are of the standard museum variety, with costumes and fashion sketches of the main characters or an original script draft from Mario Puzo, complete with red-pen notations and revisions from director Francis Ford Coppola. The feature which, alone, is worth the price of admission, though, is a stunning re-creation of the set for Don Corleone’s office, the room where the first definitive sequences of the film are staged. Perfect down to the Nth detail, the area is the kind of stunt only Hollywood could pull off; the illusion of something that was an illusion in the first place.

What gives the entire set its greatest ring of authenticity, however, is the duplication of the minimal lighting that was used by cinematographer Gordon Willis, a deep universe of shadow that threatened to swallow everyone in a menacing murk. The veteran film maker had to drastically re-invent whole processes to get acceptable exposure on the severely under-lit set, and the Academy Museum’s replication of that atmosphere is what most excites visiting photographers. To get clear, noise-free results, handheld, with today’s digital sensors, most of which can crank their light sensitivity up to levels undreamed of in the film world of the early 1970’s…well, it’s like some nerd shooter’s fever dream. And Hollywood, in the worldly wise words of Sam Spade is, indeed, the stuff that dreams are made of.

HELLO, IT’S ME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Through his nightmare vision, he sees nothing, only well

Blind with the beggar’s mind, he’s but a stranger

He’s but a stranger to himself– Steve Winwood / Jim Capaldi

NEEDLESS DISCLAIMER DEPT: THE SELF-ABSORPTION OF HUMANS IS NOTHING NEW. Still, by itself, it can’t completely account for the virtual tsunami of photographic self-portraits that has flooded the cosmos over the last generation. Due mostly to the cell phone revolution, snapping yourself has never been technically easier. Additionally, the instant feedback of the digital era has allowed us ample opportunity to experiment, quickly and over a wider spectrum of results, making for more keepers, which, in turn, makes for more attempts, which….well, you get it.

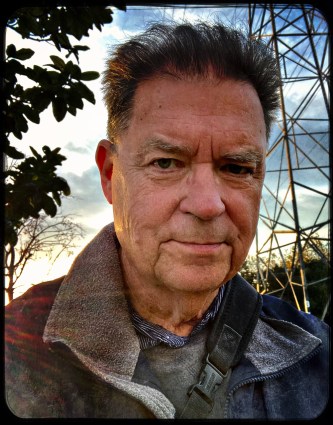

What hasn’t always kept up, in the age of photographic narcissism, is how well we actually know our subject…that is, ourselves. You’d think that a lifetime of living inside our skin would give us a decided advantage on how to present ourselves effectively or honestly in an image, but you’d be wrong. I certainly can deliver a passable version of myself on those rare occasions when I try, although over the last decade I am making a lot fewer attempts, perhaps because I see such a chasm between what I’d like to look like and what I must, actually, look like to others.

The shot you see here is my first take on a “me” shot in about eight months’ time. This selfie drought is due in part to the fact that I’ve moved to a new town, and there is so much new stuff out there to shoot that I haven’t felt the need to turn the camera around. It’s also a measure of how “over it” I am with seeing my own visions of myself come up short. And, of course, there’s also the possibility that I am just not that fascinating a subject to begin with (hold your applause) and that I am naturally drawn to more compelling subject matter. It’s just really odd, this strange state of knowing so little about how to visually interpret the same clown you’ve seen in the mirror since you were tall enough to reach over the sink. Are all selfies partially true? Mostly lies? Interpretive delusions we’ve sold ourselves? Stark reminders of our limits or fragility? All of the above?

I see one hand raised in the back. Let’s you and I have a coffee and talk it over.

The rest of you are dismissed.

MY FAVORITE DESTINATION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

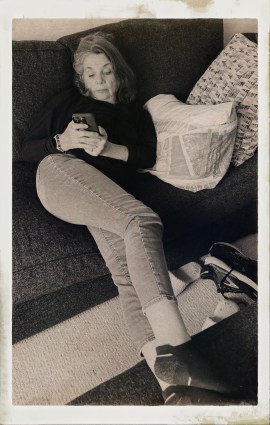

AS ALREADY STATED IN EARLIER EPISTLES from this little gazette, 2024 was, in every sense, The Year Of The Great Uprooting. In reality, we only moved one state over, from Arizona to California, but in a broader sense, we changed nearly every aspect of our daily lives. After twenty-five years in the Phoenix desert, we changed our entire life context by plunking down just ten minutes from the Pacific Ocean in the coastal town of Ventura. For a photographer, it was like being thrown into the middle of a three-ring circus of fresh visual stimuli; the best possible reset of the senses. It was if I had never seen mountains, or the sea, or farm fields before; I was living like a native but shooting with all the spastic zeal of a vacationer.

Still, with all that fresh fodder of making pictures, I find, on the last day of 2024, that my only possible choice for Most Important Photo Of The Year must, must, must be the candid of my wife Marian that you see here. In many ways, it’s the very definition of ordinary, in that I have shot hundreds of such images of her over our nearly twenty-five years together. However, the feeling that shot through as I happened upon her scrolling her phone in our new apartment, was the same one I get every time I feel compelled to grab a camera….an urgency, based on the belief that this moment must be saved.

Why not a shot of the beach or the hills ’round our new home for the “most important” of ’24? Because Marian is the real reason we landed here. It was her tenacity, her belief, her intense focus that kept me on task and fixed upon the final result during months of preparation; her conviction that, after years of daydreaming, we could actually make the leap to a new life. I am certainly a dreamer, at least when it comes to creative things, but I am something of a layabout, even a bit of a dimwit, when it comes to making practical arrangements. And so the look you see here, the slow-burning, sexy, amazing look I’ve enjoyed for decades, a perfect blend between serene beauty and keen awareness, jumped into my brain in the moment, jumping likewise into a very deep recess in my soul, reminding me why I decided, so long ago, that I had to have this woman in my life. As my life. And so, even though many scenic landscapes and local wonders from our new surroundings are sure to follow, this is the picture that defines the year, and so much more, for me. My favorite destination.

AT THE CORNER OF “WHAT THE” & “WHERE THE”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS ARE AS MUCH ABOUT CONDITIONS AS OBJECTS. The first grand age of picture-making was chiefly about documenting the physical world, recording its everyday features like waterfalls, mountains, pyramids, cathedrals. The earliest photographs were, in that way, mostly collections of things. Next came the birth of photographic interpretation, in which we tried to record what something might feel like as well as what it looked like. Conditions. Sensations. Impressions.

One thing that will invariably send me grabbing for a camera is when two seemingly disparate things create a unique relationship just by been juxtaposed with each other, as in the image you see here. The cheek-by-jowl relationship between the imposed order of Manhattan and the sacrosanct green space of Central Park has always been, to me, the ultimate study in contrasts. Acres of trees, lawns, playing fields, lakes, rolling hills, footbridges, and walking paths surrounded by a yawning, jutting canyon of steel and stone; the logic of the engineer yielding to the dreamy randomness of Nature.

The crags seen here just yards away from the skyscrapers of Central Park West look less like rock formations than the debris left after a war, as if the towers just beyond were somehow spared from an aerial bombardment. The contrast between order and chaos (and our shifting definitions of both of those terms) could hardly be sharper; so stark that, after shooting several frames of the scene in color, I decided that monochrome might better sell the entire idea of selective destruction, almost like unearthing an archived newsreel. The man on the upper left edge of the frame and the one standing alone in the gap between the rocks and the buildings both, to me, resemble the morning-after teams that might tour the damage a the previous night’s raid, salvaging what they can from the wreckage. Thus do photographs of things become documents of conditions, of the intersection between “what the” and “where the”. It’s a strange, and occasionally wondrous, juncture in which to find oneself.

New year-end galleries! Click on the tabs at the top of the page for new 2024 image collections.

SCENE OF THE CRIME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS ONE OF THE ONLY AREAS OF MY LIFE in which I am never, ever really finished. Job over? No more visits back to see the old office gang. I’m gone. Move to another city? Lose my number. I won’t be back this way again.

10:0739am, 9/16/07 on a Sony DSC-W5; f/5.6, 7.9mm, ISO 100, 1/200 sec.

But making a picture of something just once, and leaving it at that? No, let’s think more in terms of a carousel. Miss the brass ring on one revolution? Get ready to grab for it on the next go-round. That landscape could be just a little stronger. That skyline could be improved by another try (or another three dozen tries, if I’m honest). It’s sad, but true; there aren’t but a few of the images I’ve made over a lifetime that I don’t imagine might be improved by a do-over.

That point was driven home to me again recently when I found myself walking past the precise spot in New York City where, in 2007, I first attempted a shot of the 30 Rock tower, the anchor of Rockefeller Plaza and pretty much on the bucket list of any visitor to The Apple. The original shot was passable, i.e., not truly embarrassing, and I even had an enlargement of it hanging in my workroom for more than a decade, having told myself that the image, basically a snap from a Sony Cybershot in full auto mode, was pretty much a home run.

11:0419a, 10/14/24 on a Nikon Z5; f/9, 28mm, ISO 100, 1/500 sec.

Zoom forward to two months ago, when, once more, I was standing along the southern side of Saks Fifth Avenue on East 49th Street looking across Fifth Avenue at the entrance to one of the two lesser plaza buildings that stand a block in front of the main tower. Even though I was now using a full-frame mirrorless Nikon Z5 with about a billion more options built into it, I shot the picture fast, just as I had done it in ’07. Later, I was struck at how many differences I saw in the two quickie snaps, fourteen years apart from each other.

Most noticeably, I had positioned myself much closer to Fifth Avenue in the re-do, eliminating the huge black block created in the original by the shadowy side of Saks, thus revealing more of the target. This closer framing also got rid of the light pole in the ’07 shot, which is either “urban atmosphere” or clutter, depending on your viewpoint. Of course, the Nikon is far more capable of delivering more nuanced color than the ancient Sony, and the custom settings I had dialed in to an assigned aperture priority button also helped deliver a wider overall range of tones than the earlier camera could ever dream of.

As to any other key differences, the verdict is yours as to what worked better when. I did not take the recent shot with a deliberate mission in mind; that is to say, I was not so much trying to consciously improve on the original, wanting instead to shoot the new frame quickly and instinctively, as I had done back in 2007, allowing whatever changed instincts I had accrued over the intervening years to dominate over any intentional calculation. It thus stands as a fairly honest testament as to the evolution of my style, or changes in how I “pre-see” a picture. Who knows? I may revisit the scene again in 2041, perhaps as the Ghost of Snapshots Past.

A PLAUSIBLE FIB

Birthday self-portrait, 2/8/25.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE HAVE SCRIBBLED MUCHLY in this humble gazette over the years about the seemingly insurmountable challenge of the self-portrait, or, more precisely, the difficulty in balancing the arts of awareness and artifice to produce one that is essentially honest. We know ourselves, but with limits; we know how to technically present ourselves, but within limits; and while we logically stipulate that any good selfie should strive be a compromise between commentary and performance, achieving that balance is something else again.

This week, I continued with a birthday ritual I began a while back in posing for the one formally planned selfie that I do per year. There are other, quicker self-snaps, some of them accidentally adequate, but I only have one day a year that I purposefully set up lighting, a specific setting, a shutter release and a tripod, spending several hours snapping dozens of frames in search of an expression that approximates my true inner mind as I’m crossing from one year to another. Each year, I take into account the images that preceded the present year, trying to vary my poses to show some other side of myself that may not have been present in the earlier editions. This year, I was definitely out to strike a contrast.

Last year, just ahead of my birthday, I experiences a week of excruciating back pain that had me bed-ridden and nearly crazed for lack of sleep. I was just emerging from that semi-hallucinatory state when I dragged myself in front of a camera for The Birthday Shoot. What emerged staggered me a bit. I was trying so hard to muster a hopeful smile, some clue that I was trying desperately to reboot my body and spirit. However, what I actually captured was about the most honest portrayal of myself as I’ve ever managed, albeit an honest portrayal of faith vainly trying to burst through a cloud cover of anguish and anxiety. It was, beyond play-acting or performance, the real me, and it scared me a bit. Even a year later, it hurts to look at it.

This year, I am in better shape physically, mentally, even geographically, having undergone a transformative re-location to California during 2024. I have a lot of actual reasons to want to answer last year’s picture with an expression of hope. And yet the world around me, which I must react to in order to maintain any pretense at art, is convulsing, twisting itself into the same pattern of pain I myself wore last year. And so you see the result here. An expression of mild amusement, as if I’m a math professor trying to decipher a tricky equation. Not real joy, but perhaps the willingness to take on the problem, as well as gratitude for being able to still be in the game. This Portrait Of The Artist As Eternal Optimist may be a “plausible fib” at best. But it’s the face I, and perhaps all of us, need right now.

Share this:

February 9, 2025 | Categories: Uncategorized | Tags: Commentary, Portrait, self-portrait | Leave a comment