TOGGLING BETWEEN TRUTHS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

If you can’t do it right, do it in color.——-Ansel Adams

THE MAN MANY REGARD AS THE JEDI MASTER OF PHOTOGRAPHY could be said to have had a sizable blind spot when it came to his preference for monochrome over the course of his long career. Part of his distrust of color came from the fact that black and white afforded him a degree of fine technical control that emerging color systems of his time could not yet rival. Another part of his bias stemmed from the fact that he accepted that mono was a departure from reality, a separate realness that he could manipulate and interpret. In his time, color was closer to mere recording; garish, obvious, and, for him, the opposite of art.

By contrast, the world we live in has been dominated by color images for so long that we can easily develop our own prejudice regarding its opposite….that is, to see monochrome as less than, as if, by choosing not to use color, we are somehow shortchanging our art, performing with one hand tied behind our backs, doing more with less. Of course, black and white photography is in no immediate danger of dying out, proving that it has a distinct and definable purpose as a storytelling medium. Further, mono can, in fact, engender its own counter-snobbery, as if certain kinds of work are more “authentic” because we purposely limit our tonal palette, like writing a minimalist melody. Both views, when taken to extremes, can cause creative paralysis, since there is no way to prove or disprove either argument’s rightness or wrongness. There is only the pictures.

Mono image taken as one of three rapidly snapped frames, each one using a different pre-assigned preset in real time.

Over the past few years, I, like many, have tried to provide myself with several choices when capturing an image in real time. With a number of different film emulations pre-assigned to my camera, it’s easy to erase risk by just clicking from one such custom setting after another, taking the same scene in, for example, a faux Fuji transparency style, a simulated Kodachrome look-alike, and a custom monochrome profile reminiscent of classic Tri-X film. I don’t always elect to do this much coverage on a shot, but there are times when I worry about whether I’m making the right decision in the moment, and so I find the extra coverage reassuring, as if I’m improving the odds that something will work out. There is plenty of room in the photographic world to accommodate more than one kind of visual “truth”, and the most creative of us must be willing to toggle between them with flexibility and ease.

RETURN TRIP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“HEY!!!”

A very young, high and urgent voice from nowhere in particular.

“COME BACK HERE!!!”

Who come back where? Oh, wait, the sound seems to be coming from straight ahead, but I can’t see…

Oh, there’s something….

A small blur with a blue tail on it streaking off to left, followed, an instant later, by a small boy, emerging from the front entrance of a coffee bar that occupies the corner parcel of a retrofitted apartment building in downtown Ventura, California. The blur is, in fact, his dog, and the blue tail is his leash, and boy, is he bulleting out of the joint, heading down the street at Tireless Puppy Speed, pursued by his young master. Me, I’m shooting architecture in the neighborhood at the moment, which is why I find myself directly opposite the java joint, armed with a camera, but too slow to actually catch Fido’s escape. However, I have faith that I will soon get another bite at the apple.

And so I do, as Young Master catches up with the little one within half a block and proceeds to march him back to the coffee shop entrance, giving me a chance to squeeze off a series of shots of the two framed against the incredible blue of the SoCal sky and the lumpy off-white of the long adobe building. It’s a great time of day for long shadows, as witness the shade cast by the wall-mounted sign, but I wait to get the boy clear of that to keep the shot simple; just two small figures against the broad, empty canvas of the building. Young Master is moving at a fairly slow space, giving me the luxury of planning a bit. Frame number three is the one. I have been largely taking pot luck with the other shots of the morning, but this one opportunity redeems all the meh results from the session. That’s the way street work happens; on its own terms, with little notice and just a quick clue that something worth having might be on the way.

Like Tireless Puppy, you just need to sense when a door is opening, and be ready to run.

cONFRONTATIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Photography is the simplest thing in the world, but it is incredibly complicated to make it work–Martin Parr

THOSE SHOOTERS THAT WE DUB “STREET PHOTOGRAPHERS” all share a secret; that what most of us casually regard as “reality” is nothing but the top surface on a layered cake, a topography that we drill down into, in order to reveal the profound beneath the obvious. England’s Martin Parr, who passed at the end of 2025, began his career doing straight documentary work, and gradually evolved a whimsical, even gentle mastery of street work that showed everyday people, bearing their social masks, even as it revealed the biases and beliefs that underlie them. In the hands of other photographers, his approach might have been considered rude, even intrusive, but, being British, Parr practiced, instead, a kind of lower-case “C” confrontational style.

Parr, born in 1952, first aspired to be a documentary photographer as early as age thirteen, influenced by the work of the the U.K.’s Royal Photographic Society. Laboring with hit-or-miss grades in school, he found a true home at a local polytechnical academy, joining the ranks of local reporters on any and every kind of news assignment. His first truly personal approach to photographing people came as a result of his move from a city to a rural environment, where he studied the regional rituals and habits of working-class locals in an effort to to develop an eye for the humorous reality beneath their public selves, publishing Bad Weather, the first of what would eventually total over sixty collections of images, in 1981. As he moved from journalism’s then-dominant medium of black-and-white to color, he began to frame his work at a much nearer distance (using a macro lens), creating portraits that in many cases were little wider than head shots.

The range of hues and contrasts in his color shots became even more startlingly invasive as well, as he usually employed a full flash or flash ring at very close quarters. The results were revealing, if seldom flattering. “The fundamental thing I’m exploring, constantly, is the difference between the mythology of the place and the reality of it. Remember, I make serious photographs disguised as entertainment. That’s part of my mantra. I make the pictures acceptable to find the audience, but, deep down, there is actually a lot going on that’s not sharply written in your face. If you want to read it you can read it.”

Parr’s pictures were technically of the faces that his subjects presented to the world, that is, the way they believed they were best seen. His genius lay in recording that curated version of “the truth” while showing the persons beneath the mask, not in a predatory or mean sense, like a Diane Arbus might work, but in a kind of knowing smirk, as if to say, “aren’t we all very silly, after all?”.

Martin Parr’s influence extended to his stints as a lecturer, a documentarian for television, and a university professor, with his images evolving from studies of consumerism and the rising British middle class, as well as studies of global tourism and a half dozen other projects, all done with the effect of stripping away society’s outer veneer to provide a glimpse of the actual motivations that lurked below. “Unless it hurts, unless there’s some vulnerability there, I don’t think you’re going to get good photographs”, he once remarked, adding, “I see things going on before my eyes, and I photograph them as they are, without trying to change them.I don’t warn people beforehand. That’s why I’m a chronicler. I speak about us, and I speak about myself.”

GO BACK ONE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I FIRST HEARD THE PHRASE “RUN AND GUN” applied to street photography in a lecture by the great Joe McNally, a lifelong pro and official worldwide Nikon ambassador and the author of superb tutorials like the classic The Moment It Clicks, who used the term to describe the practice of shooting quickly and intuitively with a minimum of fussing about gear and a deliberate intention toward the instinctual. Trained in rapidly-evolving journalistic environments, Joe was every bit as facile in clicking away at a rapid clip as he was in his most prepared and staged images. This means, despite the term’s wording, that “flexible” is a more important trait than “fast”.

When I must shoot a lot of things in a short space of time, as when I am walking alongside my New York-born wife, who definitely has a “Manhattan stride” and is definitely on a time line (usually a brisk one) to get somewhere and do something, I find that I must make many decisions in the moment. This does not merely mean racking up as many shots as I can physically click off and hoping for the best. It comes down to evaluating situations in the moment, trusting my first instinct on what may or may not constitute a worthwhile shot, and at least being prepared to execute without excess delay.

Obviously, at the end of a R&G day, this results in a fairly bumper crop of images, the value of which can not always be seen when upon first view. The certified killers certainly stand out, as do the abject clunkers, but the vast number of shots in between those extremes sometimes take a while to reveal themselves. I myself have built up the habit of looking back on a given shoot at the distance of at least one year, as it erases many of the first judgements you made about the pictures and allows you some objectivity, as if you are evaluating someone else’s photos, which in a very real sense you are.

Upon my earlier reviews of pics taken on a fairly quick walk through Greenpoint, Brooklyn almost exactly a year ago at this writing, this young woman got lost in the shuffle. She had a special quality, but I was uncertain as to my execution, and so moved on to more obvious prize winners. It’s a sucker bet to act as your own photo editor anyway, as your choices are fraught with both bias and bad habit, but waiting a year can make you look at things in a far different way from when you first chose to click the shutter. Of course, some times you decide that your “blue ribbon” entries from that time aren’t quite the miracles you originally thought they were. But, when a smile comes to you from an unexpected place, well, that’s the whole ball game, innit?

DAYCARE CASUAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE THINGS THAT DISTINGUISHES THE VIBE in small towns is the variable definition of what constitutes “public space”. Where do people actually gather? Where are social interactions transacted? What is the familiar hang, the “everyone goes there?” Photographers who find themselves even temporarily out of their own neighborhood elements are constantly searching for the answer to the “where it’s at” question in the places they’re cruising through.

I’ve never seen a puzzle and game play space inside a Starbucks, or, for that matter, inside the average courthouse, city hall or bar. But inside a coffee house in the small coastal town of Morro Bay, California, it’s obvious that whole families, kids and dads and moms, are frequent players, stopping by for a cappuccino or espresso, a bun or croissant, and….a few chill moments with a jigsaw puzzle. The coolest part about encountering this mother-and-child team in the joint was how unremarkable they seemed. The local feel for this cafe was more than “everyone is welcome”. It was all the way to “whatever you need”. And then some.

No other customers in the shoppe seemed to acknowledge this micro daycare center activity; it was obviously just part of the daily rhythm, what made the town the town. I was only about eight feet away from the pair when I snapped this, a single-frame go-for-broke frame. I was so afraid of either making them feel as if they had to pose, or, worse, feel violated by my presence. But there was just so much life, real life, in the scene. I’m glad I had my shot.

NOTHING IS EVERYTHING IS… NOTHING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS AN OLD VAUDEVILLE JOKE WHERE ONE COMEDIAN ASKS THE OTHER, “so what is it that you do?”, to which the other replies, “nothing.”. “Well, then, says the first, “how do you know when you’re done??” Yes, I know, stupid, but it also explains exactly how I feel when I’m on photographic walkabout.

There is a big difference between having “something” to shoot, i.e., a defined plan or target, and having “whatever”, or, some might say, “nothing” to shoot. The former is for things that you intend, that you want chronicled in a certain manner. Such a shoot may include a few random shots, but the chief objective of the outing is to accomplish a set thing. By contrast, in doing a walkabout, a “wherever my feet lead me” kind of shoot, you are on a much simpler path, in that nothing you do really matters, and the whole experience can be based on pure impulse.

Walkabouts happen frequently for me, since I am notoriously early for every appointment, and many of my family are just as predictably late. And since I am never without some kind of camera, my default action, when I arrive ahead of schedule, is to just start wandering and snapping. At the very least, all those “non-pictures” will teach me a little bit more about whatever kit I’m using, and at the most, I may come home with a surprise or two, such as the image seen here. It’s about as much “of the moment” as it can get, as I was merely walking through a parking garage when its red neon sign appeared overhead through a patterned atrium tunnel. The juxtaposition of the two, mounted against a jet black sky, said take a shot. Not two, or five, or anything that might constitute a deliberate act; a pure distillation of let’s see what happens. And what you see here is all there was; no backstory, no context, no procedure.

Why is this important? Perhaps it’s a reaction against the anti-instinctual habits we acquire over the years, as our gear becomes more complicated and our technique becomes more multi-staged. Perhaps it’s good, once in a while, to reconnect with the kid that originally was so fascinated by the taking of pictures that he/she couldn’t click fast enough, couldn’t wait to get to the next raw sensation. When I can’t find that kid, I panic a bit. His hunger to Plan Later, Just Shoot can still feed something important in me. He makes a big fat itch of himself sometimes, and until I scratch him, I feel a bit lost.

THE WONDER OF THE WALKABOUT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM ASTOUNDED BY PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO UNERRINGLY APPREHEND the essentials of the ideal framing for a composition. And, believe me, they are out there; artists whose eye immediately fixes on the ideal way to launch a narrative in a static shot. The legendary Henri Cartier-Bresson was one. He reputedly kept his camera hanging around his chest until the very instant he was ready to make a shot, whereupon he lifted his Leica to his eye, and snap, one flawlessly framed image after another. The photo editor’s dreaded wax pencil never defaced his images in search of crop lines or a way to trim away fat to make HCB’s pictures communicate more effectively. There was no “fat”. The editor was already looking upon perfection.

For me, composition is more typically trial and error, and so my favorite subjects are things that will more or less remain in place long enough for me to literally walk around them in search of their “good side”. or the angle that best serves the visual story I’m after. Street photography offers up some opportunities for such focused study, but, in that real-time environment, the stories are often morphing too quickly, and one has to trust to instinct to nail that one second of eloquence, since a follow-up or re-take may not present itself. But, when I can, I try to be slow, deliberate. To do things with purpose and on purpose.

Digital, and the luxury of nearly endless numbers of exposures with immediate feedback, has been a life saver for me in a way that film, God bless its little analog heart, never was. This instantaneous concept-to-result cycle has saved many an image for me, since I am granted the ability to make a lot of wrong pictures very quickly, thus arriving at the right picture with more efficiency. The gentleman seen here in two frames was very accommodating in ignoring me, allowing me to squeeze off perhaps fifteen shots as I walked from his rear left side to his rear right side. Along the way, the scenery and props rose and fell as focal points, subtly changing the message of the photographs. Were I expert enough to follow Cartier-Bresson’s example, the image just just above might have been my goal, but, as I dwell among mere mortals in Photo-Land, I find myself by getting lost a bit. I go on walkabout.

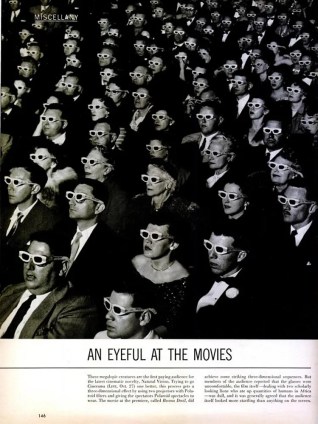

CHANNELING THE MIGHTY “MISC”

A famous snap at a 1950’s 3-d movie audience from Life magazine’s popular “Miscellany” page.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I GET THESE MOMENTS.

If I were the talent of a Henri Cartier-Bresson, the protean street photographer, I might call these brief flashes of humanity/absurdity, and the the pictures they produce “The Decisive Moment”, HCB’s phrase for the perfect collision of factors snatched from the timeline at precisely the correct instant to make something magical. As it is, at my level, such moments are more like “things that make you go ‘hmmm'”. Same aim, vastly different results.

As I have mentioned before in these pages, in my youth, the weekly arrival of the new Life magazine at the house was something of an event. Many illustrated news digests, in that golden age of periodical publication, tried to hit the perfect balance between essential current events coverage and “man in the street” photo essays, but Life, for my money, remains the standard. My favorite feature over the years was always found on the final page, just inside the back cover, a one-more-for-the-road picture called “Miscellany”. The photos in it were apropos of nothing beyond themselves. They weren’t connected to a hard-news story or editorial content. They were merely bits of whimsy, most of the “can you believe this happened/can you believe we shot this?” variety. Fun stuff.

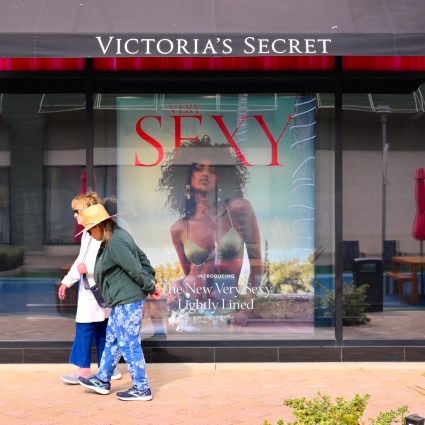

You Talkin’ To Me??, February 2024

I still feel those images in my bones during street work. Bizarre juxtapositions of the beautiful and profane; strange meet-ups between the serious and absurd. In the case seen here of the two mature ladies walking past a recruitment poster for some kind of foundation fantasy, I saw these ladies approaching from just outside my right periphery while I was composing what would have been merely a shot of the shop window. As they walked closer I realized that they were going to cross in front of it, and, just like that, my brain clicked in Miscellany mode. How could I not bring the two factors together. It was ridiculous. It was fun. Click.

Photographs can often act as comedy relief, or at least a safety valve, against the buildup of pressure from issues that hang on us far too heavily. Sometimes you just have to step back and smile. Or remind others too. Channeling the mighty “misc” is one way of getting there.

SUM OF ITS PARTS

I’ve just seen a face / I can’t forget the time or place where we just met / she’s just the girl for me / and I want all the world to see we’ve met……. John Lennon/ Paul McCartney

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN IT COMES TO STREET PHOTOGRAPHY, there is a reason that we use the phrase “a face in the crowd” rather than “the face in the crowd”, because, just as there is no single solution to the challenge, “go shoot a sunset” there can be no one face that satisfies the desires of every photographer. The combination of features, textures and expressions that compose the human visage come together in billions of combinations, some of which will entice and enthrall us, others that will repel us, and yet others that may not register at all. The human face is one of the grand, miraculous intangibles of visual art, which is why, centuries after old man Da Vinci laid down his brushes, we still can’t agree if the Mona Lisa is coquettish, innocent, wise, or a dozen other states of mind. And that’s great news for picture-making.

If I were to be assigned an essay to try to explain why the face of this young woman spoke to me on a certain day and a certain place, I would get an “F” or at least an “incomplete”. How can you quantify any of this? The face’s appeal can’t be reduced to mere physical beauty, since that phrase, in itself, produces no general consensus. Terms like plain, homely, comely, intriguing are likewise useless in describing what makes a photographer, or a novelist or a painter or a songwriter, for that matter, want to glorify a particular person. And then, beyond that, as Lennon & McCartney put it so well, there’s the random circumstances behind the discovery of the face:

Had it been another day / I might have looked the other way

And I’d have never been aware / But as it is I’ll dream of her tonight…

There are many, many things captured in an image that have no objective reason to be there, but the human face might just be the one thing that absolutely confounds any attempt to answer the question, “but why that one?” Some mysteries are impenetrable, and, wondrously, should be allowed to remain so. The truth is simple: I’ve just seen a face.

SNEAKING WITHOUT SPOOKING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

No zoom on hand, and yet I see a potential story happening at the center of a very wide frame. Take the shot anyway? Abso-photo-lutely.

THERE IS A DELICATE BALANCE TO STREET PHOTOGRAPHY, which is really spywork of a kind. Just as wildlife shooters tread carefully so as not to flush birds to flight or startle feeding fawns, street snappers must capture life “in the act” without inserting themselves into the scene or story. Quite simply, when it comes to capturing the real eddies and currents of everyday life, the most invisible we are, the better.

Part of the entire stealth trick is about making sure that we don’t interrupt the natural flow of activity in our subjects. If they sense our presence, their body language and behavior goes off in frequently unwanted directions. Undercover shooting being the aim, then, it’s worth mentioning that such work has been made immeasurably easier with cel phones, simply because they are so omnipresent that, ironically, they cease to be noticed. That, or perhaps the subjects regard them as less than “a real camera” or their user as less than threatening somehow. Who knows? The thing is, a certain kind of visible “gear presence” is bad for business. That said, telephotos can become attractive simply because, shooting from longer distances, they are easier to conceal. But is that the One Best Answer?

Same story, severely cropped, but with more than enough sharp detail to deliver the central idea.

To carry as little gear as possible as well as keep things simple, I mostly do “street” shots with a fixed wide-angle prime lens, meaning that I simply won’t have a telephoto as an option, nixing my ability to hang back from a great distance undetected. And yet I seldom feel handicapped in staying fairly far from my subject and just shooting a huge frame of what could be largely dispensable/ croppable information once I locate the narrative of the shot within it. In fact, shooting wide gives me the option to experiment later with a variety of crop-generated compositions, while shooting at smaller apertures like f/16 on a full-size sensor means that I will still have tons of resolution even if half of the shot gets pared away later.

Another consideration: besides being bulkier/easier to spot, telephotos have other downsides, such as loss of light with each succeeding f-stop of zoom, or having problems locking focus when fully extended. Your mileage may vary. The top shot here was taken with a 28mm prime. about a hundred feet away from the water’s edge, but the cropped version below still has plenty of clean, clear information in it, and it was shot at half the equipment weight and twice the operational ease. These things are all extraordinarily subjective, but on those occasions when I come out with a simpler, smaller lens, I don’t often feel as if I’ll be missing anything. For me, the first commandment of photography is “always be shooting”, or, more specifically, “always take the shot.”, which means that the best camera (or lens) is still the one you have with you.

SELF-LEGENDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Let me kick my credentials.

Ice-T, Back On The Block

A HUNDRED YEARS AGO, THE WORD WAS “BALLYHOO“, a term for the most salient trait of Americans; self-promotion, the proud and loud announcement that we are here. Ballyhoo has assumed many forms, being at once proclamations about who we are; statements of who we hope to be; agendas for what we want you to think; claims about what we have to sell or bargain with; reminders about how much respect we demand; warnings about our boundaries; rules of engagement, for good or ill.

“Self-legending”, and how it makes its way into our every visual communication, is perhaps the most American of American qualities. We didn’t single-handedly invent mass communication or advertising, but we certainly promoted and perfected the fine art of ballyhoo in ways that are still modeled the world over. Photographs of our urban landscape are a blur of our various brags, boasts, promises, and promotions, along with the hard truth that, like it or not, you must deal with us. Americans are almost fatally allergic to being ignored, and so, simply announcing is never as good as shouting through a megaphone, or, in graphic terms, making the colors bolder and the letters bigger. We visually bellow at each other like barkers in a carnival or competing vendors in a street market.

In making their enduring images of life in this country in the twentieth century, masters like Robert Frank and Walker Evans often shot frames that were almost completely composed of signage. Today, those time freezes are a valuable resource for marking what our priorities were in bygone eras; the various announcements of merchandise, company names and prices anchor the pictures in specific dreams of specific times. Nearly one hundred years on, we use different tools to, in Ice-T’s phrase, “kick our credentials”, but the same urgent need to be noticed, to be heeded, goes on, albeit in new guises. I can never photographically take the measure of a city without trying to contrast old and new signage, original inscriptions and names along with the newest refits from a Starbucks or a McDonald’s. Photography is the first art in the history of the world that is equal parts reportage and interpretation, and trying to learn how to see humanity amidst all the ballyhoo will always make for legendary pictures.

I GOTTA WORK TOMORROW, BUT……

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS I CRUISE MY WAY CAREFULLY TOWARD THE END OF YET ANOTHER YEAR, I have the distinct sensation of coming to a slow, smooth landing after having descended through a bank of dense storm clouds. Having made pictures for over half my life, I find my mind, near year’s end, riffing through a stack of images that now serve as a catalogue for the markers and milestones of more than two thirds of a century, as if my existence somehow compiled one of those kids’ flip books that, when properly thumbed, looks like a continuous movie.

And as November careens toward December, I find that I want to slow the movie down. I want to celebrate moments that were miraculously, often accidentally, destined to be frozen, evergreen, in my mind. Trying to determine what pictures within a year earn the title “keeper”, I am also rotating past earlier years, to purer and purer depictions of joy that I could never have created myself, but was blessed to be witness to. This is one such picture.

2016.It is a summer Sunday evening in Seattle, Washington. I have never walked through this neighborhood before, but the joyful whoop of this street party has drawn me blocks away from my hotel. I am enjoying the long, golden sunset hours that are a photographer’s bounty in that part of the American Northwest, and I am drawn like a magnet to these wonderfully free and frolicsome people. The music is loud, the dancing is carefree, and the mood is lighter than a dandelion seed on a breeze. This is what happiness looks like.

I know nothing about who sponsored this shindig, be it the parks department, a bunch of friends, or just the sheer life-affirming impetus of a summer night. It matters little what started, it or why: what matters is that, when I enter this space, I never want to leave it. However, I know I am bound for other places, and so, if I must leave, I’m taking a souvenir.

Click.

One of the things I love most about this picture is that nearly everyone in it is present, attending to some other person or persons. They are there, not scrolling, not checking their Instagram, but immersed in the miracle of being with other human beings. Tomorrow, they have to work. Tomorrow, they have to report to someone, fulfill deadlines, make plans, cut their losses.

But here, in this frame, it ain’t tomorrow yet.

And it never will be.

TRACE OR NO TRACE?

How do you like your pizza photo? With a guy…?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHING PEOPLE IN THEIR NATIVE SETTINGS, that is, making pictures of what they do in order to explain what they do, is the essence of street work. We are fascinated by people being “caught in the act of being themselves” (as the intro to the old show Candid Camera used to state), and we get a ton of context on all the stuff we’re seeing in a frame when we see where human activity fits into it all. I get it.

And yet, I still find myself evaluating the impact of an image with a sort of “trace or no trace” choice. Do the people in the picture explain it, actually anchor it, or am I (we) merely in the habit of sticking them there, like punctuation in a sentence? Can we comprehend what the photograph is about, and what part humans had in its meaning, without the actual presence of said people?

..or without?

The pair of shots you see here, taken seconds apart in a funky urban pizzeria, are the latest pair to present me with this conundrum. Certainly the cook in the top image conveys scale to the surrounding oven and fixtures. For example, with him in the frame, it’s easy to convey the size of the interior space, i.e., it’s pretty compact. He also “looks the part” in that he looks like he fits in a pizzeria, that is, he’s well cast in his part.

But look at the second image, which was taken after he ducked briefly into the kitchen. You get many of the same cues and clues. You get atmosphere from the distressed brick in both the walls and the oven. Indeed, without the chef to distract you, you might actually linger longer over the details in the oven itself, which unmistakably screams pizza. I suppose the reason I dither with this dilemma is the fact that I’ve often been forced to suggest the presence of people in various still lifes and architectural compositions, either because they’re not part of, say, a museum exhibit, or because they are dead or absent for more mortal reasons, leaving me with only their leavings from which to tell a story.

Even if we (or you) can’t come up with a consistent rule, the point is that not all people make a photographic story richer. Sometimes they are mere pieces of furniture, props if you will, added for balance. You alone must decide whether they’re a necessity or mere window dressing.

STUMBLING ONTO SECRETS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

REGARDLESS OF WHETHER YOU CONSIDER YOUR PHOTOGRAPHY TO BE JOURNALISTIC BY NATURE, you will, over the course of your shooting life, have the visual evidence of other people’s stories dumped into your lap. In most cases, it’s the physical aftermath of some human event that you are arriving at after the fact. Leave-behinds from a mystery. Who left this here? What happened here? Who made this, and why?

Photogs regularly stumble onto other people’s secrets, or at least the litter of secrets. People abruptly break camp and move on from the site of their strangest whims, leaving clues that may or may not make their original intentions clear. And since we take just as many images of the things we don’t understand as those we think that we do, we snap away at the strange archaeological digs people abandon when they go on to the next thing in their lives. The fact that we don’t comprehend just what it is that they left behind doesn’t make the pictures any less compelling. In fact, quite the contrary.

This office chair was discovered just where you see it, under the golden canopy of a single enormous palo verde tree in full spring blossom. The shady seclusion of the scene seems to indicate a desire to shelter, to escape, to carve out a quiet spot of contemplation. And while that may indeed be the case, the whole thing invites a lot of other questions. Why this chair? Was it the person’s favorite, or, conversely, a perch so hated that dragging it here was the next best thing to lugging it to the town dump or pouring lighter fluid on it? What was motivating enough to transfer a chair from the nearest office suite (about a tenth of a mile away) and finding a place where it could be left with no fear of discovery? Was the site scouted, or merely happened upon? How many times did the person come to sit in the chair, and why and for how long? Was it the object of reward (in an hour I’ll be able to escape to the chair) or some kind of desperate relief (if I don’t get away from these people, I’m going to just lose it..)?

One picture conjures all of this, and more, additional plot lines which I’m sure even the casual viewer can supply without much effort. That’s the beauty of even the untold stories captured in photographs. They tell us enough to keep the seeker coming back for more. We think, as photographers, that we want to reveal everything, but, in reality, many of our most treasured images are of other people’s secrets, unrevealed, and, hence, irresistible.

THE STREET GIVETH…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S BEEN CALLED SPYING, PRYING, PREDATION, and, occasionally “art”….the strange cross between eavesdropping and journalism that is collectively known as “street” photography. The elements of it that reveal something universal or profound about the human condition are hailed with exhibitions and awards, while the worst of it is considered rude, intrusive, even cruel. For those of us who only want our picture taken when we give specific permission, or when we are “ready”, street work can feel like theft, that is, something that is stolen from us. Then again, it also, sometimes, nails the truth about someone else’s vulnerabilities or foibles, and that, miraculously, we seem to be able to live with.

In a world in which billions of images are snapped globally each day, and in which most shutters are absolutely silent, and flash is on the endangered species list, it seems as if we have long since passed the point of no return in terms of privacy. We emotionally demand it even though we have no logical right to expect it. Every day there are more and more places where cameras can not only intrude, but intrude with laser precision, and we must reluctantly admit that, effectively, we are all under surveillance, always.

We have almost unlimited access to everyone’s quiet inner moments, at least the ones they play out in public. Does everyone deserve to have every part of their life laid bare, and who is to decide? If you come upon a private moment, such as the one seen above, does slicing off a sample of it for public use cheapen that moment? Or does it in some way celebrate it as emblematic of something essential about being human, something we all recognize, even share?

I shake up all these arguments on a day-by-day and frame-by-frame basis, and I don’t always come up with a coherent answer. The street giveth and the street taketh away, and photographers pluck their harvest from it like an army of insatiable fruit pickers. Are we bad? Are we wrong? Can anyone say for sure?

LIFE LEAKS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE CAMERA IS THE MOST INTRUSIVE INVENTION EVER UNLEASHED ON THE WORLD, and the world has been altered forever by its peering, prying eye. That is both a negative and positive statement.

It has to be, since the fruits of photography are, on a good day, a mixed blessing. This unique bit of Industrial-Age machinery has, over several centuries now, investigated, invaded, illuminated and violated all of us. We simultaneously embrace this phenomenon and recoil from it. We hope its all-seeing orb won’t expose our particular secrets, but we cannot look away when it probes the dark truths of others.

Like many, I shoot through open windows as I walk through neighborhoods. I record what I tend to call “life leaks”. I maintain what I tell myself is a respectful distance, working hard not to capture anything starkly intimate about the lives that are concealed within houses, apartments, shops. I am only after shards, suggestions. Hints at the real wonders within. After all, it’s not, strictly speaking, my business, is it? Or might it be?

The camera, at any given time, is engaged in several ongoing chronicles of horrors and triumphs of the human condition in various global “hot spots”. It has ever been thus. We look in on people’s daily toils, invited or not. We are peepers. This is not always a good thing, nor is it always a bad thing. Sometimes, as in the image shown here, our curiosity about how people live is rather benign. Look at the way the light plays inside that house. Oh, what’s that picture on the wall? What’s around that corner, I wonder? Other times, our curiosity is reportorial, even prurient. What happened to this building? Is there anyone left alive inside? Who did this? It’s a short walk from childlike wonder to journalistic horror shows. I wonder where the line is.

I wonder if there even is a line.

Since the invention of the camera, we are all witnesses. And we are all subject matter.

I worry about walking a tightrope between wanting to know and demanding to know, and how we can all stay aloft on that rope. I don’t have a one-size-fits-all answer. We, every one of us, has to make that call one image at a time.

STRIKE A POSE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

STREET PHOTOGRAPHY IS GENERALLY ABOUT CAPTURING PEOPLE in their most natural element, freezing the more narratively interesting samples from their daily activity. In theory, the format really offers a fairly infinite number of quick examinations of virtually every trait and pursuit, promising a lot of visual variety in the depiction of the human condition. However, over the last twenty years or so, an increasing number of pictures of people on the street seem to be about more and more of the same thing: fixating on our phones.

You must have noticed by now that random images of people on the street are, in more cases than ever before, pictures of them watching screens. Texting. Tweeting. Dialing. Reading. In a world in which we do more of our private business out in public, our engagement has gone further and further inward, ever more insular, isolated. This is not a critique of the value of these precious devices, or a wish that they somehow be magically uninvented. My point is that their ubiquitous use presents fewer opportunities for exploration of human behavior by the street photographer, since, even though our phones are holding us spellbound, the way we look when we’re on them is, well, boring.

This 21st-century “look” is a strange sort of update of the facial aspect of photography’s first era in the 1800’s. In a time when exposures took a long time and people were just beginning to formulate their relationship to this invasive eye known as a camera, people tended to look frozen, solemn, as if they were only reluctantly granting admittance to the blasted thing. They stood at attention, staring blankly, their faces a cipher. Later on, we learned to love the camera, to mug and model and talk to it, a habit that still shapes our candids at intimate moments or the tidal wave of selfies we create.

On the street, however, that is to say, on our way to something else (all our various something elses), we are facially as lifeless as a Victorian-era farmer posing for his first daguerreotype. Thus the man in this image, already physically alone by virtue of the space he occupies, is doubly isolated by his further act of pulling away into his phone. A key part of him, a part that has always been a basic element of street shooting, is simply not available.

Does this trend alarm you? Do you find yourself approaching street work in a fundamentally different way because of it? Or is the job of a photo-observer to merely record what he sees, or in many more cases, what he sees being withheld?

FROM BEAUTIFUL TO BLEAK AND BACK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Main Barber, 1968 (Courtesy of the estate of Fred Herzog and Equinox Gallery)

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

FRED HERZOG (1930-2019) MAY BE ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT PHOTOGRAPHERS you’ve never heard of, just as there are hundreds of other unsung heroes in the slow transition of street photography from a medium dominated by monochrome to one defined by color. Indeed, it is because of Herzog and others like him that we now regard color as not only a valid tool for street work, but, for some, the only way to fly. However, it took a long time to get to this point.

By the time Fred began shooting almost exclusively in what we now call “un-re-gentrified” neighborhoods in the Vancouver of the 1950’s, he had earned his bread with less fanciful work as a medical photographer and fine arts instructor. At the time, the raw, immediate feel of black & white film was still the world’s go-to. Color films were thought to be the domain of amateur snapshots or high-end magazine ads. Monochrome was stark; color was pretty. How could any serious art shot depict the real state of mankind in the plump, primary tones of Kodachrome?

Granville/Smythe, 1959 (Courtesy of the estate of Fred Herzog and Equinox Gallery)

Herzog shot not only what he wanted, confining himself to the same small knot of neighborhoods for most of his shooting life, he shot how he wanted, and Kodachrome was his go-to. Vancouver was run-down and worn, but it was also bursting with a kind of bumptious neon flavor that would have been stripped away in black-and-white. In an age that said that color would beautify (and thus blunt) a picture’s reportorial impact, Herzog set out to demonstrate, in one iconic image after another, that color didn’t soften the harder edges of his world; it actually fleshed them out.

Technology, or rather its slow evolution, kept Fred’s work from being properly seen until years after he had created some of his best work. Kodachrome was a very slow reversal film which defied even the best labs’ efforts to create good qualtity prints, and so Herzog kept the results largely to himself in slide format until the world caught up, delaying the first public exhibition of his work until 2007. The wait was worth it, as his full body of work became one of the most valued studies on a single locality in photographic history. Herzog managed to chronicle the rise, fall, and resurrection of a city in a sprawling portfolio covering more than a third of a century, but, more importantly, he has become, with every passing year since his death in 2019, one of the greatest prophets of the full power of color, not to merely make life warmer, but to render it more completely. Time has vindicated his instinct, the feeling that life, rendered in all its natural hues, could still register the complete range of human experience, from the beautiful to the bleak, and do it faithfully.

SWEET CLAUSTROPHOBIA

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ENOUGH WITH THE FLOWERS.

Give the birds a rest. Put the quiet trails and placid sunsets on pause.

I want my skyscrapers back.

Yes, I’ve dutifully done my photographic confinement therapy, like everyone else whose worlds have shrunk during the Great Hibernation. I’ve lovingly lingered over the natural world, embraced the tiny universes revealed by my macro lenses and close-up filters. I’ve properly marveled at the wonder of simple things, patiently revealed in the quiet composure of a more inward kind of photo-therapy.

It was needful. It was even helpful. Hell, on a few days, it was essential. But instead of steady, slow inspirations into the deepest reaches of my lungs, I now long for shallow, quick breaths, terse inhalations of monoxide, stolen as I dash across a crowded crosswalk. I want to dodge things. I want to run for a train. I need to see the infinite collision of brick, stone, and steel textures all fighting for my visual attention in a mad crush.

I want to hear noise.

I can make myself comfortable, even modestly eloquent, shooting the splendors of the natural world. God knows we have placed too many barriers of estrangement from our inheritance in field and flower. But I have known, since I was a child, that my soul synched perfectly to the unnatural world, the arbitrary creation of we wicked, weak bipeds, with an affection that is every bit the equal to that which I feel for a tree or a blossom.

I see the same geometry and design in our crude imitations of nature as in the contours of the rose or the patterns within a cactus flower, and I’m not embarrassed to say that the spires, arches, bridges and alleyways that map our densest interactions give me an electric thrill. I should also add that I am not typical within my family, where there are far more Thoreaus, all centered on their respective Waldens, than there are Whitmans, who see glory in even the failed strivings of the urban experiment. I take comfort in my sweet claustrophobia, and I make no apology for the fact that my photography breathes its fullest in cities.

There were, of course, millions for whom, during the Horror, cities were a cruel prison, and I absolutely get that. As the Eagles said, we are all just prisoners of our own device. Artists can create a heaven or hell in any setting, as witness the miraculous faith of prisoner poets or the inventive tinkering of a Robinson Crusoe. Confinement is largely a matter of geography or physical constraint, but, as we have all spent a long year discovering, it can be overcome by a refusal of the mind to remain locked into a particular place.

Still.

I have not yet completed my slow trip back to the hunting grounds where my cameras talk loudest to me. Like the start of our communal imprisonment, it will come in layers, in a million tiny shards of re-discovery. But it will come. My cities will be restored to me. My flowers and birds and bugs will always be celebrated as the protectors of my sanity, of the need to take my art inward from time to time. But right now, I need to get out on the streets, and see what’s up.

VERITIES AND VARIABLES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FIRST OFF, LET’S AGREE ON ONE THING: photographs are not “the truth”. Well, at least not what we think we mean by truth. Maybe we use the “reality” of a captured image as a mere point of departure, the place we start off from, on the way to…well, that’s up to the artist, innit? What I’m trying to say here is that merely snapping a picture doesn’t mean that you’ve told the absolute truth about what your lens was pointing toward. Only the bones of truth…a structure on which to drape the rest, through interpretation, and the shared experience of inviting other eyes into the discussion.

Some of our inherited thinking about the veracity of a photo (“the camera doesn’t lie”) is that it is produced by a machine, a device inserted between our vision and the finished product, a mechanism that we associate with reproduction. After all the device measures light; it is indifferent, just as a seismograph or a lie detector would be. Only it isn’t. We humans are interacting with that “recording” function at every turn, just as personally as the painter measures and controls strokes of a brush. And then there’s the consideration of time. We don’t capture all of life in our box, just a stolen sliver of it, which guarantees that the sample, having been yanked out of its original context, is tainted from the start.

Even the best picture, then, comes out compromised, depending on how it was taken, and by whom. Clicking a shutter may be a means of producing something thought provoking, even profound, but it is nothing as simple as capturing the truth. As illustration: it’s easy to identify all the contributing elements of the above image….light, shadow, color, water textures, solid objects…but it was only possible to combine them all into the result you see here for a single moment. Someone else, working with the very same elements just a second later, would likely produce vastly different results. And yet, both of us are “right”.

Thinking of photographs as truth is tricky business. Consider this quote from photographer Giles Duley, who has garnered some distinction of late as what I call a camera-oriented journalist:

“I don’t believe there’s such a thing as ‘truth’ in photography. As soon as I walk in a room and point a camera at you, I’ve already ruled out the rest of the people. As soon as I press the shutter on that second, I’ve ruled out the rest of the day. There is only honesty….”

A photograph is something used to illustrate a point of view. It’s not the only point of view to be had, and so it can’t be the absolute “truth” for everyone. But that’s the beauty of it, the fascinatingly infinite variety of “my truths” to be had in the artistic realm. This is not science. Science is different. You can’t present your “version” of gravity, or photosynthesis, or the speed of light. They just are. Art happens in the realm of “might be” or “could be”, and our photographs are, at their best, suppositions, suggestions. This picture might be true, and it might not, and so let the debate begin. And that is what makes the creation of image an art. Because it’s yours, and, with luck, it might be ours, and the dialogue that decides that is, well, everything.