BACK TO EDEN

The task I’m trying to achieve, above all, is to make you see.—-D.W. Griffith

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY YEAR OR SO, OVER THE NORMAL EYE’S FOURTEEN-YEAR JOURNEY, I tackle anew the task of explaining the choice of that particular name. That means proposing a kind of working definition for the word “normal”, or at least putting forth the reasoning behind my own use of it within these pages.

For me, to be “normal” is to operate within the first, natural state of something. And when it comes to the making of photographs, that means the first state of the human eye. The “factory setting” for your eye is observation, not merely “seeing”. As a new human being coming into the world, you don’t just believe what you see; you believe in excess of, even in spite of what you see. That which we call “factual” is fluid, colored by experience, and certainly not formed by data alone. Only after we leave childhood are we trained to think that are eyes are only to be used for documentation or recording, for evidentiary work. At that point, we stray from the “normal” state of our eyes, the vision we were equipped with, as a default, when we first came to be.

However, once you pick up a camera, you actually leave the plainly factual behind, since you are already utilizing a machine that, on its best day, can only generate an abstraction of “reality”. By making images with that machine, you are already weighted in favor of interpretation, of seeing past your senses. And that restores your ocular factory setting or default. Your soul, in effect, gets rebooted.

It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.—-Picasso

Pablo had the right dope: we have to unlearn the bad training, foisted upon us by the world, about what’s “important” to look at. We have to re-learn the ability to trust fancy. That is the only path to art. If our eyes were merely designed to make a visual document of the world, we would only have to take a single photography of any object on earth, as only one would be necessary. Instead, we honor sentences that begin with “the way I see it is..” We are moved by photographers with normal eyes. That’s what this venue is, and has always been, about. A return to Eden, if you will. A reassertion of innocence. To believe that what we have to say about the world is, indeed, normal. For us.

AN AUDIENCE OF ONE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YEARS BACK, MY FATHER, TAKING NOTE OF MY OBSESSIVELY FASTIDIOUS MANNER OF WATCHING MOVIES, i.e., free of interaction with my fellow audience members, remarked that, in a perfect world, I would have my own private projection room, watching films in perfectly controlled environments as a fussy, controlling audience of one. Unfortunately, that dream film-critic scenario never presented itself.

Until this year.

Turns out, if you want to share a movie with a minimal number of people, go see a sixty-year-old French art film in the middle of a weekday afternoon. We’re talking guaranteed crowd control here. Marian and I had driven from Ventura, California to a quaint cinema high in the hills above Santa Barbara, hardly the venue to catch Godzilla XXXIV: The Final Reckoning or any other cinematic Hoover designed to suck in the public by the millions. Upon taking our seats, it soon became obvious that we would have the entire house to ourselves, a true rarity. Additionally, ahead of the curtain time, the theatre was not pumping a firehose of advertisements and idiotic on-screen trivia quizzes into the room, but, instead, bathing us in pure, wonderful silence.

It didn’t take long for me to realize that, there, at that moment, I could take a picture of Marian that would be impossible in 99% such cases. There was that face in the middle of a sea of muted red. The image would compose itself! Three frames and I was happy enough with the Edward Hopper-ish result to sit back down and dig the quiet. I knew I’d stolen something precious out of the darkness.

Fifteen minutes later, a few other people drifted in (the film had a French plot, meaning no plot, so it really didn’t matter when they arrived) and the moment was gone. But I had at least obeyed my instinct and had the great fortune to make a record of it. That is the heart and soul of making a good picture, and I’ll sit through someone else’s lousy one, anyday, to make that happen.

FITS AND (FALSE) STARTS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ERGONOMICS is defined as “the application of psychological and physiological principles to the engineering and design of products, processes and systems.” When it comes to photography, the term “good fit” is probably the simplest way to express this concept. Cameras engage the hands, the eye, and the mind with each click. The question to be asked of any camera then, is, “how is this machine helping me make better pictures with a minimum of fuss and delay?”

The term “human factors engineering” (HFE) is sometimes used instead of “ergonomics” and I actually like that phrase better, since it says exactly what the designer’s goal should be; making things so that they are easy to operate in an efficient and satisfying manner. So let’s apply that idea to the various dials, buttons and menu options on a camera, and where they are situated. Does your device cause you too many tasks per image in terms of calculating, reaching, holding, executing? Many of the most elegantly designed pieces of kit in photographic history have also been some of the worst nightmares when those stunning sketches leave the inventor’s table and enter the real world of shooting. And so, what makes a generally operational camera not work for you must be the primary consideration when you’re shopping, more so than features, price, or high marks from techie reviewers.

In a 2012 article called Camera Ergonomics, revised for 2023, a common operation done by a very popular model (name withheld) was outlined to illustrate the frustrating processes that were baked into the camera by its designers:

“When we want to operate the front control dial, there is not enough space for the right index finger to bear on it without moving the other fingers of the right hand out of the way, so we have to release our grip on the handle with the third or fourth fingers, move those fingers down the handle, move the index finger forward and down to the front dial, rotate it, move the index finger back up to the shutter button, release our grip with the third and fourth fingers, and move them back to their regular holding position. This is seven different actions, two of which involve moving the entire hand…”

Sadly, many of us simply make the adjustment in ourselves when presented with an obstacle placed in our path by the camera. We make ourselves fit the device instead of vice versa. This is madness. Any thinking review of a new camera should focus primarily on what it’s like to use the thing, because anything else simply builds extra, time-wasting, shot-missing junk into the process.

Never mind that cameras currently come loaded with enough tricks and toys that will never be fully used over their useful lifetimes, or that the snarl of intertwined option menus on many machines is a jungle all on its own. Take it down to the most basic and essential issue; if the camera literally requires you to contort your body beyond its natural functions just to take a picture, it is the device, not the human, which merits a re-design.

FAKE IT ‘TIL YOU TAKE IT (OR EVEN LATER)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE SO MANY VARIABLES IN STREET PHOTOGRAPHY, from composition to exposure and everything in between, that it’s a minor miracle that any useful pictures ever get made, by anyone, anywhere. Being that street work is even more subject to hazard or random accident than any other kind of shot, the shooter must negotiate dozens of factors before squeezing off a frame. Contrary to popular terminology, this process produces the very opposite of a “snap shot”, in that nothing is completely controlled, and most everything is unanticipated.

Frequently, when I first sort through images back home, I discover that Nature or Chance gave me a bit of a boost in making a picture work slightly better. On the day I took this shot of Jane’s Carousel) in Brooklyn Bridge Park opposite lower Manhattan, I was mostly concentrating on the interactions of parents and kids as they queued up for the ride, and occasionally trying to frame to include the bridge, which is very close by. I typically don’t try to convey motion in such shots, snapping at a quicker shutter speed to keep everything frozen for the sake of faces. In the case of this carousel, exposure was also a bit tricky, since it sits inside a glass enclosure topped by an overhanging roof which also includes atrium-like cutouts. That’s a lot to handle at one time.

So much, in fact, that it wasn’t until days later that I realized that shooting through a closed side of the carousel’s glass box would, in effect, filter the carousel through a wiggly warp of sorts, creating the sensation of whirling or spinning. In fact, close examination reveals that most of the details are, in, fact, in fairly sharp, normal focus, but the slight distortion lent a dreamy quality to both the original shot at the mono conversion, both of which I submit here.

Whatever “plan” you try to make in advance, street work places you at the mercy of prevailing conditions, and so it’s better to be gracious/grateful for the odd bits of luck that are thrown your way. As soon as you become cool with the knowledge that you’re not actually in charge, you can just get out of the way of the entire process and chalk up an occasional win.

THE CASE FOR REINCARNATION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE HALLMARKS OF A MATURE SOCIETY is a healthy respect for its own history. When a nation is busy a-borning, doing anything “for the ages”, from physical infrastructure to laws to philosophy, can get lost in the blur of just…becoming. The dust of Now is just swirling too madly to get a good view of what can, or should, be made to last. Change is so rapid that it becomes its own religion. Preserving, protecting, salvaging things….that comes later.

American, a country that has always surged forward too quickly to allow ourselves much of a backwards glance, was always more about building than keeping. Things that became outmoded or obsolete were quickly consigned to the national scrapheap. As a result, we only recently have begun to place a premium on conservation, on re-purposing our past. And nowhere is that more evident than our cities, where signs that read “soon, on this site” usually mean that something old must first be destroyed. We have taken a long time learning to give things second lives. Including ourselves.

The foyer of the restored Citizens Building, a 1917 bank-turned-condo community in Columbus, Ohio.

I have a special affection for the urban spaces that get “saved”, that are lucky enough to survive the wrecking ball and shine forth anew, escaping the fate of so many things we mistakenly label “improvements”. Not everything old is immortal, certainly, but not everything new is magical, either. I love to take my camera to renovations, grand re-openings, conversions. It is a great privilege to see, in a place’s original design or materials, what its creators did. In the case of the above image, taken inside a 1917 bank in Columbus, Ohio that’s been recently reborn as luxury urban condominiums, one sees many original features that brought beauty and elegance to a financial institution that work perfectly well, thank you very much, as features in a residential building. I document these small victories because they are still too rare. I long to demonstrate, for as many eyes as I can, that “past” need not mean “dead”. As our country, or any young country, grows up, it’s easier to see what seemed invisible when we were young and in a hurry. That’s true of ourselves no less than of our creations.

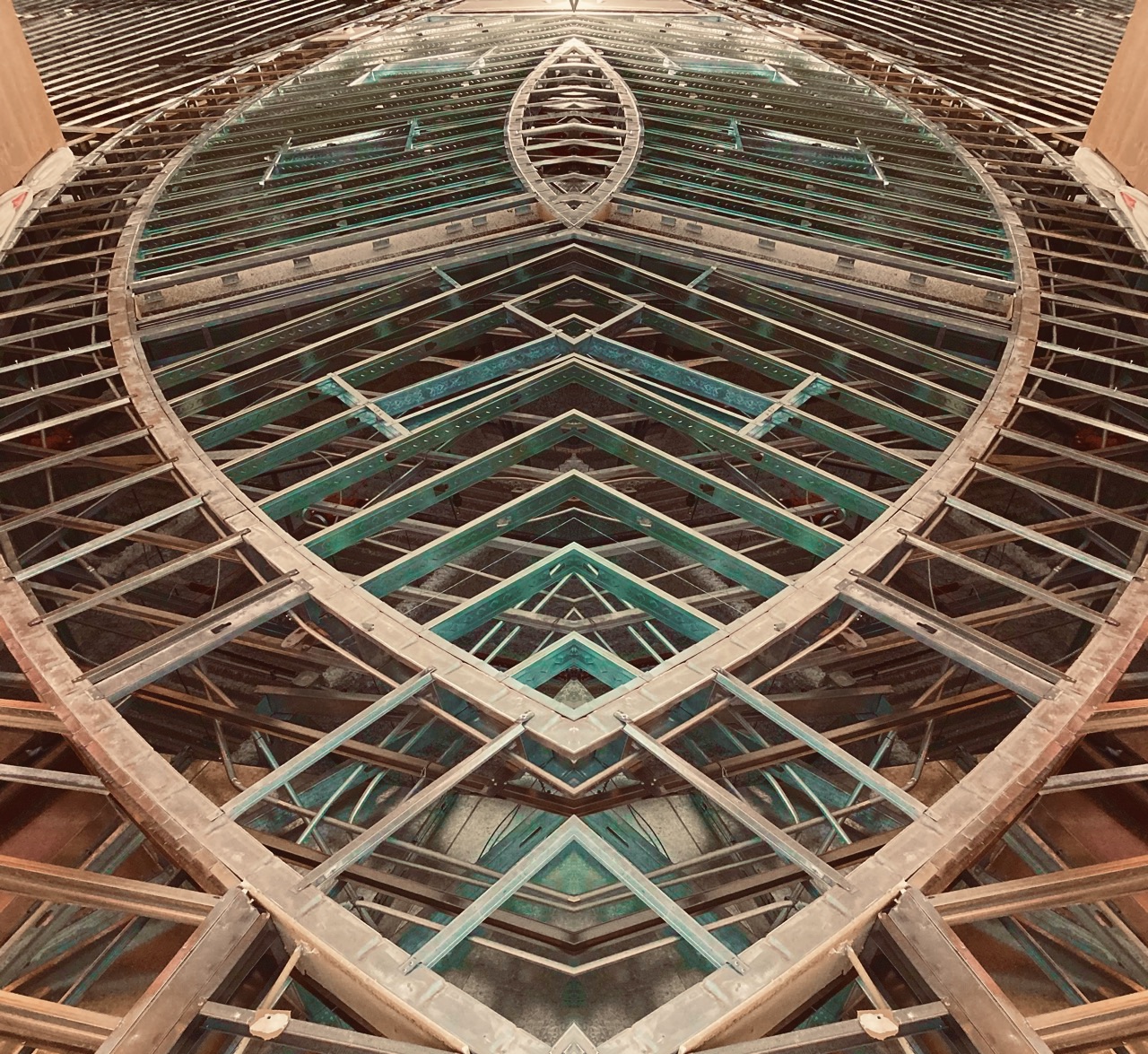

BOTH SIDES, NOW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THOSE OF US WITH ROOTS IN THE STONE AGE may recall the opening of the old Disney TV series Wonderful World Of Color, which consisted of a burstingly brilliant kaleidoscope, endlessly unfolding behind the show’s title card. It was a stunning way to display the infinite rainbow of hues of the early color network broadcast, echoing what everyone had seen when turning those little cardboard tubes filled with rattling bits of color glass; the hypnotic appeal of the symmetrical.

From ancient architectural frameworks to medieval tapestries to the intricately balanced frameworks of common spaces in the present day, we love to imitate the visual counter-balances seen in nature, such as the patterns within a flower, or the delicate web of design in a snowflake. And, as photographers, especially in an age in which anything can be manipulated or faked to our heart’s content, we are often seduced by the temptation to artificially impose that balance on our images, to make the world uniform and orderly. Why is this visual urge so strong?

A genuine fake. Because reality is, you know, just reality…

Psychologists claim that humans take a kind of comfort from “balance”, feeling more rooted, in, for example, inside a church that has four matching wings conjoined by a central hub, or a wagon wheel, or a plaza built around a square mosaic. There are even studies that indicate that we think of symmetrical faces in other people as more attractive than non-symmetrical ones. Small wonder, then, that we deliberately simulate symmetry where none naturally exists. As in our younger days, when we first folded sheets of paper into fourths, then cut pieces out of them that, once unfurled, replicated the cuts four times in perfect opposition to each other, we use photographs not only as proof of natural balances, but as a jumping-off point toward the creation of Other Worlds, better ones with a neater, more mathematical precision. We play Creator, or at least Re-Creator.

Which to a say, in roundabout fashion (my usual method), that photographs are only marginally documentary in nature. They evolve from ideas that may or may not reflect the actual world. That’s why they aspire to art.

A FEATURE, NOT A BUG

By MICHAEL PERKINS

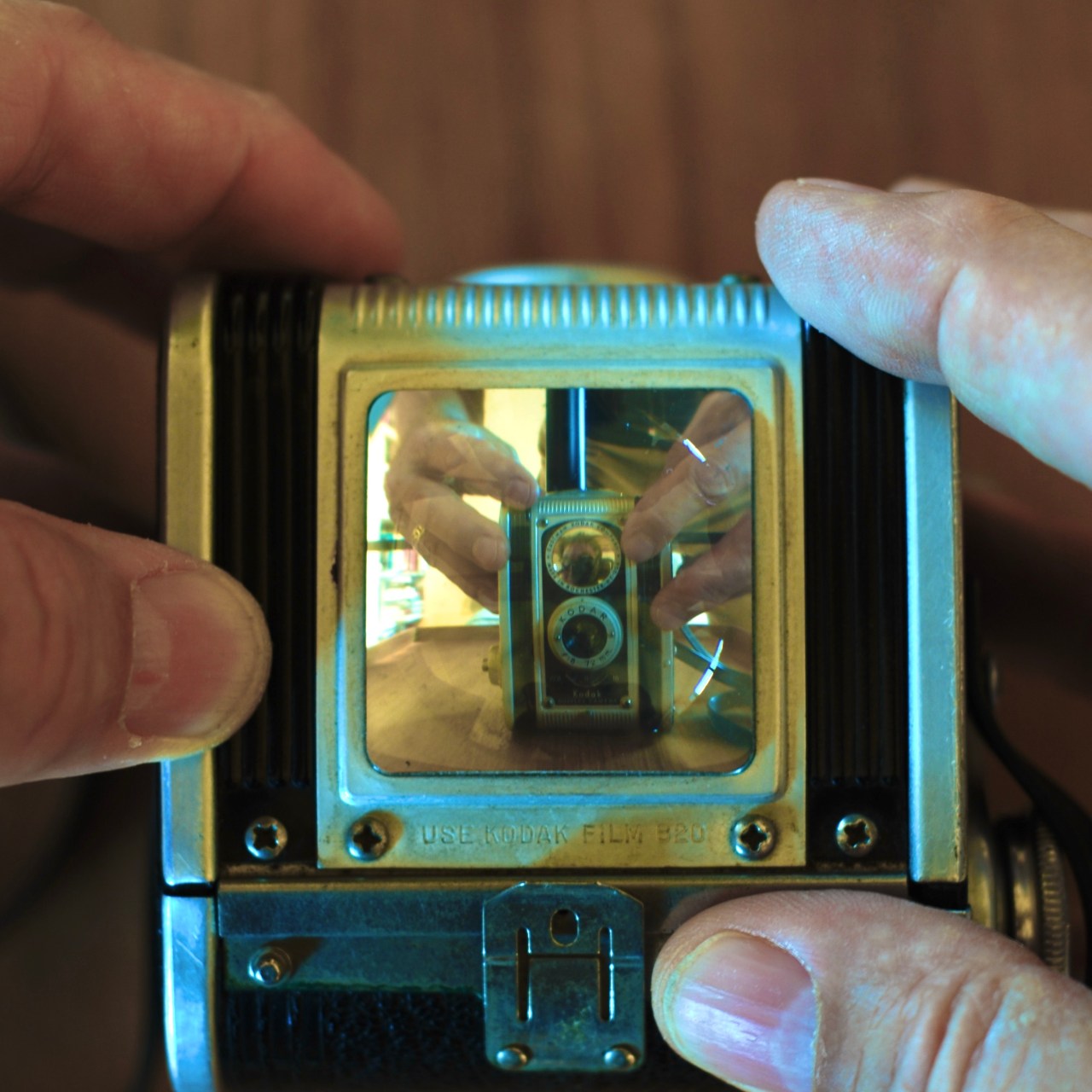

PHOTOGRAPHY IS CURRENTLY EXPERIENCING SOMETHING OF A TEENAGE CRUSH on defects, a glorification of the technical flaws in our images that values errors as something that confers “authenticity” on our work. Some of this is a recoil from the digital revolution, with shooters believing that all that new-fangled perfection is somehow suspect, less real without the glitches, miscalculations and unpredictability of analog methods. This nostalgic vibe has fired the lo-fi movement, as well as the tactile back-to-film thrills of instant photography, as seen in the reborn Polaroid brand. Some applaud this as a return to innocence, while others revile it as pretentious and faddish.

Going out of our way to purchase equipment that deliberately engineers what we used to call “mistakes” back into our work is certainly one way to approach the making of pictures. And going lo-fi by means of hi-tech is also an option, as shredding or rewiring the quality of images through apps and post-production gets the job done pretty much at the speed of whim. And certainly the ingenuity of inventors in trying to re-introduce analog imprecision back into a medium that they fear has become too cold is amazing to witness. The photo market is ablaze with new gadgets designed to make everything new look old again. But beyond achieving the novelty of an old-timey aspect, are we truly adding anything to our art?

Making a shot like this, for example, is easy, even with older gear. It’s an over-exposure, or what the artful amongst us love to call “high key”, and, upon first glance, it does have a certain impact, given the subject matter and location. But is it, finally, a better picture, or merely a novelty? Would a conventionally exposed shot have had the same impact, or even more? I have a friend who works professionally in digital but disdains it for his personal work, teaching himself how to apply collodion to glass plates and shoot everything as if it were 1850. Aside from the scientific achievement of getting and controlling an image under extremely demanding conditions, I am not convinced that the pictures he’s making are anything more than a trick from a kid’s science fair. You can only marvel at a tabletop volcano so many times before you ask yourself whether it really merits a blue ribbon.

But that’s why there is more than one approach to doing all this. I myself indulge in various effects-oriented shots, depending on what I need to do. But what I need to do, most of the time, is make sure I choose the right canvas for what I’m trying to depict. Chasing an effect for its own sake, even the seductive appeal of nostalgia, can become a dead end, lowering art to the status of mere craft.

(PLEASE DON’T) WATCH THE BIRDIE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM CERTAINLY NOT THE ONLY SHOOTER OUT THERE BEMOANING THE EFFECT OF SMARTPHONES on how people behave when being photographed. On the contrary, the way these ubiquitous and simple devices have transformed how we present ourselves to the camera has filled bookshelves with dire essays and laments, including an essay I recently discovered called The Death Of Candid Photography In The Age Of The Smartphone by Alex Cooke (read it here.) It is no longer a question of whether image-making has been compromised by the cel; it’s merely the degree to which it’s happened.

Stated simply, the very way we act when we know a camera is present (and one always is) has dramatically shifted from when cameras were formally “brought out” for selected occasions, or largely confined to studios. Having your picture “taken” has gone, within a generation, from a somewhat special event to a non-stop process of recorded surveillance. We are all always on, always assuming that a perpetual wave of photo-ops will be washing over us. This creates a hyper-alertness to keep ourselves in “take-able” mode, to constantly assess how we look, where we stand, what cultivated, managed version of ourselves we wish to offer up for mass consumption. Family photos no longer reside in albums or shoeboxes, but are expected to serve as our ongoing audition for the world’s approval.

In such an environment, there can be no such thing as the Unguarded Moment. As Cooke writes, more and more of us “have never experienced social interactions without potential camera presence. (Our) baseline behavior incorporates photo awareness as a natural state rather than a special condition.” We actively choreograph the visual geography of every frame that captures us, calculating, on the fly, how it will be received. We pre-edit our faces and figures to achieve a picture of us as we would prefer to be seen, and judged, by millions of strangers. For the photographer, especially the so-called “street” shooter, it is increasingly hard to make images of people exhibiting the full range of human experience and emotion, since everyone, everywhere, is “trying out” for some kind of approbation.

About a million years ago, people having their photograph “made” had to be instructed how to even look in the right place in order to look natural. Watch the birdie. Now, we worry, about what the birdie thinks of us; whether it likes us, whether it can be seduced into helping to market us. And, sadly, we take more and more pictures of ourselves that reveal less and less. We are, finally, a production.

HUE MONGOUSNESS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE LAST MONTH OF SPRING and the first month of summer in Ventura County, California are termed by the locals as “May Gray” and “June Gloom” for their long stretches of solidly overcast days. During that extended time-out from the area’s typically limitless supply of sunshine, I tend to experiment with variations on monochrome, given that the quality of color becomes flat and dull. There’s nothing blander to the eye than a beach town on a cloudy day.

This temporary cooling of hues usually has me playing with b&w contrast as well, since it, too is in short supply in May and June. But sixty days of gray is finally too much for my soul to bear, and I revert to in-camera color settings designed to spice up mere reality…to, in essence, fake the effect of true sunlight.

To this purpose, there are the scads of custom online settings “recipes” that shooters offer to cheat one’s way into splendor. One such sim that has made it onto my camera’s preset buttons is a fairly good fake of Fuji Velvia 100 slide film, which is a vital tool during Ventura’s annual dip into ick. As seen here, it’s really flattering to foliage and skies, if a bit surreal when it comes to reds and yellows.

Thing is, humans armed with cameras are humans that come predisposed to seek the sun, and thus open to breaking out the Crayolas to dose up on a little ersatz atmosphere. Is it enhancement? Sure. Is it “cheating” as my wife terms anything photographic beyond a straight-from-the-camera shot (including cropping)? Who knows? Who cares? Cameras are interpretive tools, not mere recording devices, and one man’s fudged workaround is another man’s miracle.

SEEK THE UNIVERSAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

To see a world in a grain of sand / and a heaven in a wild flower / hold infinity in the palm of your hand / and eternity in an hour. ——–William Blake, Auguries of Innocence

ONE OF THE MOST MIRACULOUS GIFTS OF PHOTOGRAPHY is the same gift that all great arts, from painting to music, produce; the ability to take a small sample of life and make obvious its universal connection to existence in general. To see a local sunrise is to see the same sun that every person on the planet can see; to show Blake’s “grain of sand” is to glimpse every shoreline and beach; and to show emotion on a single human face is to experience the joys and sorrows of all faces everywhere.

Seeking the universal in the particular is, of course, beyond instinctual to anyone who spends any appreciable time as a photographer. We learn from our first photo shoots how to recognize patterns and their replication across peoples and generations. We know that everything we show has all been shown before. So why restate the obvious? I guess because some instances of “all of us are everybody” strike us as particularly poignant. It reinforces the truth that all experience is shared experience.

I recently attended an elementary school graduation at a school in Los Angeles, an elegant, sweet-hearted recognition of our general humanity that, on that particular day, contrasted strongly with angry energy elsewhere in the city that underscored our divisions rather than our commonality. This particular school is a wondrous mixture of ethnic pride, a school in which no fewer than eleven languages are spoken across the student body. There were any number of opportunities to record the celebrations of various families as they arrived to celebrate the miracle of their young people, but for some reason I was particularly happy with this one, a small parade of three generations gathering to mark success, to certify our common humanity, to beam with pride. I love this picture, for reasons that go far beyond any technical skill on my part. Photography succeeds when it seeks, and preserves, evidence of the universal. We are all the same child, happy to pick up our diplomas and go to the next level. We are all cameras striving to freeze that happiness for posterity.

************************************************************

Want to review past articles? The Normal Eye is fully archived. Just click on POST TIMELINE at the bottom of any page on the site to scroll through our entire first dozen years. Thanks and happy hunting!

THE WONDER OF THE WALKABOUT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM ASTOUNDED BY PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO UNERRINGLY APPREHEND the essentials of the ideal framing for a composition. And, believe me, they are out there; artists whose eye immediately fixes on the ideal way to launch a narrative in a static shot. The legendary Henri Cartier-Bresson was one. He reputedly kept his camera hanging around his chest until the very instant he was ready to make a shot, whereupon he lifted his Leica to his eye, and snap, one flawlessly framed image after another. The photo editor’s dreaded wax pencil never defaced his images in search of crop lines or a way to trim away fat to make HCB’s pictures communicate more effectively. There was no “fat”. The editor was already looking upon perfection.

For me, composition is more typically trial and error, and so my favorite subjects are things that will more or less remain in place long enough for me to literally walk around them in search of their “good side”. or the angle that best serves the visual story I’m after. Street photography offers up some opportunities for such focused study, but, in that real-time environment, the stories are often morphing too quickly, and one has to trust to instinct to nail that one second of eloquence, since a follow-up or re-take may not present itself. But, when I can, I try to be slow, deliberate. To do things with purpose and on purpose.

Digital, and the luxury of nearly endless numbers of exposures with immediate feedback, has been a life saver for me in a way that film, God bless its little analog heart, never was. This instantaneous concept-to-result cycle has saved many an image for me, since I am granted the ability to make a lot of wrong pictures very quickly, thus arriving at the right picture with more efficiency. The gentleman seen here in two frames was very accommodating in ignoring me, allowing me to squeeze off perhaps fifteen shots as I walked from his rear left side to his rear right side. Along the way, the scenery and props rose and fell as focal points, subtly changing the message of the photographs. Were I expert enough to follow Cartier-Bresson’s example, the image just just above might have been my goal, but, as I dwell among mere mortals in Photo-Land, I find myself by getting lost a bit. I go on walkabout.

DUST WITHIN DUST

Sandwiched between a strip mall and an apartment complex in Ohio, an 18th-century graveyard..

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CEMETERIES USUALLY PROVIDE VISUAL CUES GALORE for both passersby and photographer, with hefty monuments, iron gates, placid, leafy grounds, and flower-crowned epitaphs. Most final resting places also stir in a big dollop of dignity, of august respect, a way of marking the importance of those interred below. A send-off befitting the lives they lived.

But not always.

A place of neglect instead of respect.

Grave sites, and the gravitas they receive from us, vary wildly from town to town. You might be laid to rest beneath the uniform, manicured fields of Arlington, or, as in this forgotten patch behind a strip mall in Reynoldsburg, Ohio, you might be in a random gathering of crumbling headstones hemmed in by an ugly cyclone fence, overgrown with weeds, lacking even the simplest legend on the origins of souls gone so long ago that half the data on their markers has been effaced by time. The graves here date back to the earliest days of the republic, with even a few occupants from the revolutionary era. However, to drivers whizzing by the front of the shopping strip on state route 256, they may as well be on the moon, the only hint of the site’s existence being a small post-mounted sign reading “Historical 1819 Seceder Cemetery, Behind Shops.”

In speaking to several people who live in the immediate area, I found that the fact that there was an historic cemetery moldering in neglect just yards away from where the locals drop off their dry cleaning or shop for snacks was a complete surprise. The living and the dead tend to be more side-by-side in smaller towns, and, in fact, several other, more lovingly maintained graveyards are scattered throughout Reynoldsburg. But so many things slip between the cracks of history. Time not only heals, allowing pain to be endured; it also erases, allowing loss to go unheeded, or completely forgotten. For guys with cameras, both legacies of the departed impart their own poignant pain.

AS ADVERTISED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CALIFORNIA HAS ALWAYS BEEN ITS OWN BEST PUBLICITY AGENT, burnishing its already dazzling visual beauty with idealized vistas in posters, packaging and legends that elevate the state from a mere paradise to something like a fairyland. Anchored in my midwest reveries in Columbus, Ohio, my own first glimpses of scenes of the far west were not candid photographs or documentaries, but the golden bounty of the land as depicted on fruit crate art. Long before I experienced the range of light that is a daily miracle in its mountain skies and coastal beaches, I saw it simulated like some fantasy landscape in Maxfield Parrish’s over-the-top posters for Edison Mazda Lamps. And decades before I would step off a plane to experience the Golden Gate first-hand, I marveled at postcard-perfect views of San Francisco through the lenses of a View-Master.

Now, long past all those childhood visions of California, I actually live here, and am amazed to see the same sort of light and color that I had assumed were mere hype and boast, only to find the very vistas that inspired so many brochures, magazine spreads and travel guides. The amazing thing is that the real deal is not that much removed from the imaginary when it comes this place. The shot you see here, of part of the old Santa Barbara State University campus, is pretty much straight out of the camera, although I retreived some details from the more extreme shadows. And this picture, I find, is not an anomaly, but the daily legacy of life out here.

The only thorn on this rose is what the California native knows about his Eden…that protecting it from the ravages of the very people who claim to love it can break your heart, overwhelm you with the task you are charged with, to save, serve, defend, replenish. Photography is the religious worship of light and what it can beautify. But in all that beauty is buried a challenge; we must remember that we are not owners but merely caretakers, and that we must use the arts for, among other things, reminding everyone just what is at stake. Only in that way can the wonders we cherish most about this world continue to delight as advertised.

NEW ANGELS

Current, a rope and cord art installation in Columbus, Ohio, created by “fiber artist” Janet Echelman

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ME, ONE OF THE MOST EXCITING TRENDS IN URBAN DESIGN, in the twenty-first century, is not the latest generation of skyscrapers or town plazas, but a bold new redefinition of the concept of public art. Where once it was sufficient to plop down a statute of some wartime general near the county courthouse, commissioned works now make mere sculpture look as primitive as cave paintings. We have evolved past the commemorative earthbound seraphim that once graced our parks, to flights of fancy that connect and shimmer from the air. It is an age of New Angels, and Janet Echelman is one of its patron saints.

Echelman, a Guggenheim fellow and Harvard graduate, who refers to herself as a “fiber artist”, is, in fact, an altogether new kind of sculptor. Instead of being grounded on pedestals, her arrangements of shimmering color, created by mixtures of fiber, netting and rope, hang in suspension over cityscapes like vast spider webs, refracting the rainbow and generating waves of shifting hues depending on changes in sunlight, wind or the angle of view. Some of her creations are billowing circles and cones that resemble a whirlwind of cyclone; others look like sky-bound rivers, curling and twisting into tributaries of red and blue. Each is uniquely tailored to its specific location in cities like San Francisco, Vancouver, Seattle, and a half-dozen other cities around the world. They are, simply, magnificent, and the best challenge for any photographer, since they appear vastly different under varying conditions.

I first saw one of her works while working at Arizona State University, where Her Secret Is Patience floats like a phantom hot air balloon near the school’s Cronkite School of Journalism. And just this spring, I was thrilled to see her first work to be floated over an entire intersection, 2023’s Current, which spreads across the meeting of High and Gay Streets in Columbus, Ohio, anchored to the tops of buildings at the crossing’s four corners. Commissioned by a local real estate developer as a kind of front porch for his refurbished bank building (now housing deluxe condos), Current can be seen from any approach within a four-block distance of the area, an irresistible advertisement for the regentrification of the neighborhood. Janet Echelman is but one voice in a rising chorus that demands that public art re-define itself for a new age. That age will not only withstand controversy but actively court it, just as any art, including photography, needs to do.

THE STRAIGHT (AND TALL) SKINNY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY TIME OVER THE PAST TWENTY-FIVE YEARS that I have strayed from my home in the American southwest and headed back to my mid-Ohio roots for family visits, I am struck by a stark difference in the general arrangement of architectural space between the two regions, or at least a difference that I myself perceive. It would be a monstrous over-generalization to say that legacy houses, out west, tend to be horizontal in orientation while midwestern houses in older towns tend toward the vertical. I have absolutely no empirical data to back up this impression, only the way that it strikes my photographer’s eye.

Western dwellings strike me as variants on the basic ranch house design, with many homes arranged from left to right, many without basements or attics. Midwestern homes, by contrast, seem to be narrow and high, resembling a brick turned up on end. I tend not to actively notice this distinction unless I am back home, trying to compose frames in which several buildings cluster together to suggest an entire town or street. My hometown of Columbus, Ohio, which is a sprawling city composed of many legacy neighborhoods, boasts a ton of “tall-and-skinny” sectors from the Short North to German Village to outlying villages like Pickerington or Reynoldsburg. In many of these neighborhoods in which, unlike say a city like Brooklyn, houses need not be crunched and crowded together like a row of brownstones, the brick shape still often predominates, setting up a strange contrast between wide, deep yards and narrow, stretched headstones of design.

Sometimes the look of a small town can actually seem like the view between gravestones. And, in the rural areas where the local cemetery is actually cheek-by-jowl to to the residential districts, the connection is even more compelling. I walk these Midwestern streets, once as inevitable as breath to me, and realize that not only my physical address, but I, myself, have undergone deep, deep change. And that, in turns changes the pictures I envision.

DOWN TO THE BONES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TOWNS, VERY MUCH LIKE THE PEOPLE WHO CREATE THEM, don’t pass away all at once. Over the lives of neighborhoods and villages, as in the lives of the people who populate them, there are various ebbings and flowings of health. Even years after there are no more comebacks or rebirths, decline itself takes on a slow, predictable rhythm. Streets and businesses can, indeed, take a long time to die.

America is a place where beginnings are over-ripe with hope, as if nothing that happens after the word “go” is even worthwhile mentioning. In such a place, nothing says, “this no longer matters” like the empty, featureless faces of ebbing storefronts. Once performing as mission statements for their proprietors (“now open!” “lowest prices in town!” “bargain city!”), these places start to resemble an old actress who no longer care to put on makeup of brush her hair. The buildings remain standing but their faces are blank.

Towns like this one (let’s protect its privacy) are so stripped of ornament that they become mere jumbles of rectangles, building-block puzzles with few messages outside, no hope inside. Still, as abstract versions of their old selves, they can make interesting compositions, even as their continuing existence is both mysterious and sad. We love the start of things. We avert our gaze rather than acknowledge the end of them.

I WAS A TEENAGE CAMERA-SMASHER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

JOE McNALLY, WHOSE ASTOUNDING IMAGES HAVE GRACED THE PAGES of Life and National Geographic, along with far too many other to be mentioned here, has, in recent decades, developed quite a roadshow as an ambassador for Nikon products. What began as a few simple tips and tricks eventually blossomed into a grand presentation of his greatest hits and a hilarious TedTalk-type chat about the many mishaps and near-death experiences he as accumulated in Getting The Shot. His results “in spite” were always astonishing, but the takeaway for me was knowing that there was at least one other super-talented shooter out there who was also something of a doofus. I needed, really needed to know that everyone gets their share of gasp-inducing smash-ups.

I have littered the cloudscape of Camera Heaven over my lifetime with all the devices I have dented, dashed, dropped and dinged. These include my Kodak Instamatic M12 movie camera, which I lost hold of only to watch its battery gate smashed to bits (I finished the film roll by rubber-banding it back on), a Polaroid Colorpack II which disintegrated in my hands during a wintry shoot, and two recent face-plantings followed by bad bounces for both my Nikon P900 and Z5 (both survived, to varying degrees). In most cases, the so-called “ruined” cameras continued to function after the mishaps, leaving mostly my pride or dignity as casualties. Some of my favorite shots of downtown Los Angeles, for example, were taken just minutes after the shutter on my camera froze from old-age, allowing me to nurse it through a few more crucial frames before it finally seized up for good. One such image, of the majestic Eastern Columbia building, is seen here.

Cameras live and then cameras die and we grieve and we move on. Seeing something physically damage your favorite tool is a great way to be reminded that it is merely a tool, that you take the picture to a much greater degree than any bit of gear you use to help you do it. But I still love to hear the Joe McNallys of the world admit, in front of witnesses, that they have almost dropped a flash bulb from the top of the Empire State Building or have watched multi-thousand-dollar equipment cases bubble beneath the surface of a bog in Eastern God-Knows-Where. Weirdly, it helps Little Me soldier on.

THE MOMENT IT CLICKS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER MARRIED TO A BIRDWATCHER, I WAS PRETTY MUCH DESTINED to eventually cross over into her world, especially given the natural affinity which has always existed between the two hobbies. Like the making of pictures, the science of spotting and organizing data on the world’s winged wonders is based on the thrill of discovery, a unique mix of surprise and wonder.

Eureka moments.

The sound made by a birder who’s just checked a pileated woodpecker off his “life list” is similar to the cry of joy/relief a photog makes when the plan for the image comes real. And when both kinds of people occupy the same space, it’s inevitable that the photographer will be tempted to try to capture, not merely the birds on hand, but those who get emotionally supercharged when they spot a beauty.

I have captured many manifestations of pure joy among birders over the years, since, due to my inability to see even half of what the experts see, I have lots of time to troll about looking at everything else, including the local scenery and the gleeful faces of those whose knowledge occasionally affords them a major payoff. The frame seen here encapsulates that feeling, the moment when Nature grants you The Big Reveal.

A Eureka moment.

Birding is also like photography in that there is a definite learning curve, an apprenticeship which encourages humility. Being good at anything means slowing down and waiting on the process of learning. It is never immediate, and there are no real shortcuts. Either you put in the time or you fail.

But, God, the joy if you hang in….

GOING-AWAY PRESENTS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

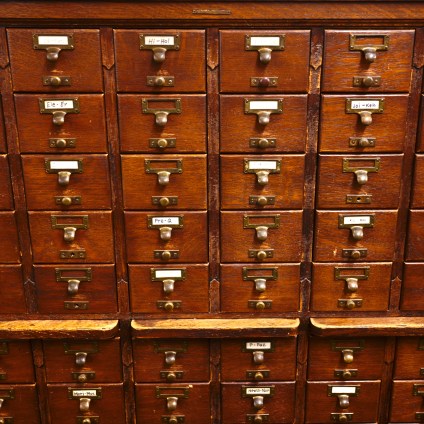

YOU MAY REMEMBER THE BRIEF 70’s-ERA FLING MANY OF US HAD with the wooden cases that were originally designed to carry the metal type used in composing newspapers and magazines. We stored them vertically on walls and stuck cute little knickknacks in the compartments, re-purposing something that once had been so universal as to be invisible to most of us into something we paid fresh attention to, now that it was charmingly obsolete.

Photography, being at least part reportage, is uniquely equipped to take note when everyday items become rare curiosities. You can take measure of this process poring through the tons of articles listing the common objects from earlier generations that later generations can no longer identify, like Rolodexes or rotary phones. Antique stores, which are mostly resale forums for other people’s old junk, are replete with things that were once essential and are now peripheral. Sometimes, the shocking distance between eras can produce good grist for images.

When the everyday becomes the vanished, like this old library card catalog, we are removed enough from them to note individual elements of them, like materials, design, patterns….all the practical aspects that their inventors had to balance to make the things. You realize that there were once several support industries just for these catalogs. Someone had to make the file cards. Cabinet makers were engaged; there were special varnishes to seal the wood, metal rods to anchor the cards in place, brassworks to make the pull handles. There were people who could sit you down and spend an evening just discussing the finer points of this catalog company versus another. Expertise was gained. Factories were engaged; people hired.

Can a photograph of an obsolete library tool evoke any or all of this? Depends. There are no guarantees that either a snapshot or a deliberately composed picture can or will do the job. But, at the very least, our understanding of earlier versions of ourselves begins with a physical document of what those people lived with, and around. And that narrative is always a potential treasure.