SMILE! OR NOT.

Since we’re usually unhappy with the way others capture us, we have nothing to lose by a making a deliberate effort to come closer to the mark ourselves. Self-portraits are more than mere vanity; they can become as legitimate a record of our identities as our most intimate journals. 1/15 sec., f/7.1, ISO 250, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A COMMONLY HELD VIEW OF SELF-PORTRAITURE is that it epitomizes some kind of runaway egotism, an artless symbol of a culture saturated in narcissistic navel-gazing. I mean, how can “us-taking-a-picture-of-us” qualify as anything aesthetically valid or “pure”? Indeed, if you look at the raw volume of quickie arm’s length shots that comprise the bulk of self-portrait work, i.e., here’s me at the mountains, here’s me at the beach, etc., it’s hard to argue that anything of our essence is revealed by the process of simply cramming our features onto a view screen and clicking away…..not to mention the banality of sharing each and every one of these captures ad nauseum on any public forum available. If this is egotism, it’s a damned poor brand of it. If you’re going to glorify yourself, why not choose the deluxe treatment over the economy class?

I would argue that self-portraits can be some of the most compelling images created in photography, but they must go beyond merely recording that we were here or there, or had lunch with this one or that one. Just as nearly everyone has one remarkable book inside them, all of us privately harbor a version of ourselves that all conventional methods of capture fail to detect, a visual story only we ourselves can tell. However, we typically carry ourselves through the world shielded by a carapace of our own construction, a social armor which is designed to keep invaders out, not invite viewers in. This causes cameras to actually aid in our camouflage, since they are so easy to lie to, and we have become so self-consciously expert at providing the lies.

The portraits of the famous by Annie Liebovitz, Richard Avedon, Herb Ritts and other all-seeing eyes (see links to articles below) have struck us because they have managed to penetrate the carapace, to change the context of their subjects in such dramatic ways that they convince us that we are seeing them, truly seeing them, for the first time. They may only be doing their own “take” on a notable face, but this only makes us hunger after more interpretations on the theme, not fewer. Key to many of the best portraits is the location of their subjects within specific spaces to see how they and the spaces feed off each other. Sometimes the addition of a specific object or prop creates a jumping off point to a new view. Often a simple reassignment of expression (the clown as tragedian, the adult as child, etc) forces a fresh perspective.

As for the self-portrait, an artistic assignment that I feel everyone should perform at least once (as an intentional design, not a candid snap), there is a wealth of new information gleaned from even an indifferent result. Shooters can act as lab rats for all the ways of seeing people that we can think of to play at, serving as free training modules for light, exposure, composition, form. I am always reluctant to enter into these projects, because like everyone else, I balk at the idea of centering my expression on myself. Who, says my Catholic upbringing, do I think I am, that I might be a fit subject for a photograph? And what do I do with all the social conditioning that compels me to sit up straight, suck in my gut, and smile in a friendly manner?

One can only wonder what the great figures of earlier centuries might have chosen to pass along about themselves if the self-portrait has existed for them as it does for us. What could the souls of a Lincoln, a Jefferson, a Spinoza, an Aquinas, have said to us across the gulf of time? Would this kind of introspection been seen by them as a legacy or an exercise in vanity? And would it matter?

In the above shot, taken in a flurry of attempts a few days ago, I am seemingly not “present” at the proceedings, apparently lost in thought instead of engaging the camera. Actually, given the recent events in my life, this was the one take where I felt I was free of the constraints of smiling, posing, going for the shot, etc. I look like I can’t focus, but in catching me in the attempt to focus, this image might be the only real one in the batch. Or not. I may be acting the part of the tortured soul because I like the look of it. The point is, at this moment, I have chosen what to depict about myself. Accept or reject it, it’s my statement, and my attempt to use this platform to say something, on purpose. You and I can argue about whether I succeeded, but maybe that’s all art is, anyway.

Thoughts?

Related articles

- Avedon For Breakfast (fabsugar.com)

- Getty Center Exhibits Herb Ritts and Celebrity Portraits (ginagenis.wordpress.com)

- Annie Leibovitz: ‘Creativity is like a big baby that needs to be nourished’ (guardian.co.uk)

A BOX FULL OF ALMOSTS

Shooting for 3D (top image) often cost me a lot of composition space, forcing me to frame in a narrow vertical range, but learning to frame my message in those cramped quarters taught me better how to draw the viewer “in deep” when composing flat 2D images.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I RECENTLY SPENT AN ANGUISHED AFTERNOON sifting through a box of prints that I shot from about 1998 through 2002, a small part of my amateur work overall, but a particularly frustrating batch of images to revisit. Even given the high number of shots of any kind that one has to take to get a small yield of cherished images, the number of “keepers” from this period is remarkably low. It is a large box of almosts, a warehouse of near misses. Still, I felt that I needed to spend some “quality time” (strange phrase) mentally cataloguing everything that went wrong. I could have used a stiff drink.

One reason that the failure rate on these pictures was so high was because the pictures, all of them stereoscopic, were taken with one of the only cameras available for taking such shots at the time. The Argus 3D was an extremely limited film-based point-and-shoot which had been introduced for the sole purpose of producing cheap prints that could be developed by any vendor with conventional processing. The resulting 4×6 prints from the Argus were not the red-green anaglyph shots requiring the infamous cardboard glasses to decipher their overlaid images. but single prints made up of two side-by-side half-frame images in full color, which could later be inserted into an accompanying split-glass viewer that came with the camera.

The 3D effect was, in fact, quite striking, but the modest camera exacted a price for producing this little miracle. Since stereo works more dramatically at longer focal lengths, only shots made at f/11 or f/16 were offered on the Argus, which also had a fixed shutter speed and could not accommodate films rated higher than ASA 100. As for better 3D cameras, most available in the late ’90’s were dusty old relics from the late ’40’s and ’50’s, meaning that any hobbyist interested in stereo photography had to pretty much accept the built-in limitations of the rigs that were available. As a result, I had only basic control over exposure; light flares would invariably create huge streaks on one of the two angled lenses, creating a headache-y “flicker” in the viewing of the final print; and, worst of all, you had to compose every shot in vertical orientation, regardless of subject, in half the width in which you normally worked.

Worse for the artistic aspect of the project, I seem to have been sucked into the vortex that traps most shooters when learning a new technique; that is, I began to shoot for the effect. It seems to have been irrelevant whether I was shooting a bouquet of roses or a pile of debris, so long as I achieved the “eye-poke” gimmick popping out of the edge of the frame. Object (and objectives) became completely sidelined in my attempts to either “wow” the viewer or overcome the strictures of the camera itself. The whole carton of prints from this period seems to be a chronicle of a man who has lost his way and is too stubborn to ask directions. And of the few technically acceptable images in this cluster of shots, fewer still can boast that the stereoscopic element added anything to the overall impact of the subject matter. Can I have that drink now?

A few years later, I would eventually acquire a 1950’s-vintage Sawyer camera (designed to make amateur View-Master slides), which would allow me to control shutter speed, film type, and depth of field. And a few years after that, my stereo shots started to be pictures first, thrill rides second. Grateful as I was for the improved flexibility, however, the Argus’ cramped frame had, indeed, taught me to be pro-active and deliberate in planning my compositions. Learning to shoot inside that cramped visual phone booth meant that, once better cameras gave me back the full frame, I had developed something of an eye for where to put things. Even in 2D, I had become more aware of how to draw the eye into a flat shot.

Today, as I have consigned 3D to an occasional project or two, the lessons learned at the hands of the cruel and fickle Argus serve me in regular photography, since I remain reluctant to trust even more advanced cameras to make artistic decisions for me. Thus, even in the current smorgasbord of optical options, I feel that, in every shot, I am still the dominant voice in the discussion.

That makes all those “almosts” worth while.

Almost.

Bartender? Another round.

Thoughts?

Related articles

BIG STORY, LITTLE STORY

Which image better conveys the romantic era of the Queen Mary, the wide-angle shot along the promenade deck (above), or a detail of lights and fixtures within one of the ship’s shops (below)?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE VERY APPEAL THAT ATTRACTS HORDES OF VISITORS to travel destinations around the world, sites that are photographed endlessly by visitors and pilgrims alike, may be the same thing that ensures that most of the resulting images will be startlingly similar, if not numbingly average. After all, if we are all going for the same Kodak moment, few of us will find much new truth to either the left or right of a somewhat mediocre median.

In a general sense, yes, we all have “access” to the Statue of Liberty, the Grand Canyon, Niagara Falls, etc., but it is an access to which we are carefully channeled, herded, and roped by the keepers of these treasures. And if art is a constant search for a new view on a familiar subject, travel attractions provide a tightly guarded keyhole through which only a narrowly proscribed vantage point is visible. The very things we have preserved are in turn protected from us in a way that keeps us from telling our subject’s “big story”, to apprehend a total sense of the tower, temple, cathedral or forest we yearn to re-interpret.

More and more, a visit to a cultural keepsake means settling….for the rooms you’re allowed to see, the areas where the tours go, the parts of the building that have been restored. Beyond that, either be a photographer for National Geographic, or help yourself to a souvenir album in our gift shop, thank you for your interest. Artistically speaking, shooters have more latitude in capturing the stuff nobody cares about; if a locale is neglected or undiscovered, you have a shot at getting the shot. Imagine being Ansel Adams in the Yosemite of the 1920’s, tramping around at will, decades before the installation of comfort stations and guard rails, where his imagination was only limited by where his legs could carry him (and his enormous and unwieldy view camera, I know). Sadly, once a site has been “saved”, or more precisely, monetized, the views, the access, the original feel of its “big story” is buried in theme cafes, commemorative shrines, info counters, and, not insignificantly, competition with every other ambitious shooter, who, like you, wants a crack at whatever essences can still be seen between the trinkets and kiosks.

On a recent visit to the 1930’s luxury liner RMS Queen Mary, in Long Beach, California, I tried with mixed results to get a true sense of scale for this Art Deco leviathan, but its current use as a hotel, tour trek and retail mall has so altered the overall visual flow that in some cases only “small stories” can effectively be told. Steamlined details and period motifs can render a kind of feel for what the QM might have been before its life as a kind of ossified merchandise museum, but, whereas time has not been able to rob the ship’s beauty, commerce certainly nibbles around its edges.

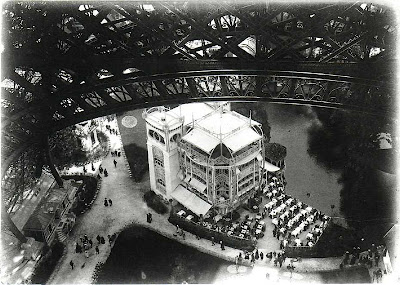

Sometimes you win the game. I recently discovered the above snapshot of the Eiffel Tower, taken in 1900 by the French novelist Emile Zola, where real magic is at work. Instead of clicking off the standard post card view of the site, Zola climbed to the tower’s first floor staircase, then shot straight down to capture an elegant period restaurant situated below the tower’s enormous foundation arches. And although only a small part of the Eiffel is in his final frame, it is contextualized in size and space against the delicate details of tables, chairs, and diners gathered below, glorifying both the tower and the bygone flavor of Paris at the turn of the 20th century.

Perhaps, for a well-recorded destination, the devil (and the delight) is in the details. Maybe we should all be framing tighter, zooming in, looking for the visual punctuation instead of the whole paragraph. Maybe all the “little stories” add up to a sum greater than that of the almighty master shot we originally went after. Despite the obstacles, we must still try to dictate the terms of engagement.

One image at a time.

Thoughts?

GLO-SCHTICK

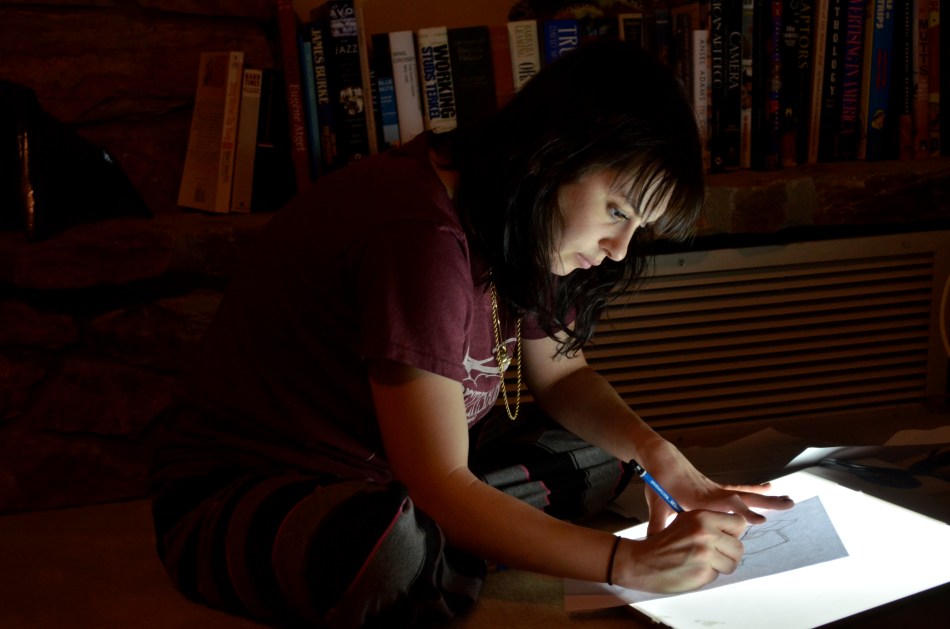

Sometimes just a bit is just enough. A bump up to ISO 640 kept me fairly free of noise and allowed me to use the screen’s glow as my only light source. 1/30 sec., f/5.6 at 52mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE BEST TECHNIQUE is one that does not scream for attention like a neon t-shirt emblazoned with the phrase LOOK WHAT I DID.

Now, of course, we are all messing around backstage, working hard to make the elephant disappear. We all manipulate light. We all nudge nature in the direction we’d prefer that she go. But what self-respecting magician wants to get caught pulling the rabbit out of a hole in the table?

I recently had the perfect low-light solution handed to me as I watched a young designer working in a dim room, and, thankfully, only marginally aware of my presence. “Lighting 101” dictated that, to get a sense of her intense concentration, I send the most important light right to her face.

Turns out, a light tracer screen, in a pinch, makes a perfect softbox.

Better yet, the light from the screen thinned out and dampened after it traveled left past her shoulders, leaving just enough illumination to keep the rest of the frame from falling off completely into black, making the face the lone story-teller. An ISO bump to 640 and a white balance tweak were enough to grab the best of what the screen had to give. At this point in the “gift from the gods” process, you click, and promise, in return, to live a moral life.

Sometimes you don’t have to do anything extra to make a thing look like it actually was. That’s better than finding a hundred-dollar bill on the street.

Well, almost.

What was your best light luck-out?

LOMO MOJO

A perfectly average handheld interior shot taken without flash in 2012. What is amazing, to an old geezer like myself, is how completely impossible it would have been, back in the day, to capture even this modest shot with the very same type of toy plastic camera now being sold to “lomography” enthusiasts and marketed as “hip”. Light leaks and color streaks do not an image make.

I AM INTERESTED MOST IN WHAT MAKES PEOPLE WANT TO TAKE PICTURES, as well as what makes them take the best ones. In that spirit, I have been recently re-examining the decade-long debate on the trend known as lomography, or the use of plastic bodied, low-tech toy cameras as serious imaging instruments. In renewing the impact of “lomo”, with its rudimentary shutter speeds and fixed-focus meniscus lenses, I have pored over four bazillion angry diatribes by those who condemn the cameras’ extreme technical limits and dismiss their enthusiasts as trendy phonies. I have also tracked its rabid defense by ardent users who celebrate lomo cameras as a way back to a kind of artistic innocence, a return to a photographic Eden in which we all shoot with our hearts instead of our heads. At the end of it all, does it matter what anyone thinks about how we take pictures if something, anything comes along to want them to take more of them? Probably not, and I certainly can’t decide the issue, if it needs deciding at all. Still, a brief re-examination of the whole concept, as I see it, might be worth a run-through. Your mileage may vary…

And, yes, before we proceed, I freely admit that a few world-class photos have been taken with cameras that are one step above drawing the image yourself with a crayon, just as a few amazing canvasses have been created by artists who hurl paint the way a monkey flings poo. I leave it to your discretion whether these accomplishments are vindication of a great vision, or happy accidents granted by the randomness fairy.

Backstory section: as a lifelong shooter, I enthusiastically began taking pictures with the very types of cameras which lomo fans so highly prize. This was dictated purely by economics, not art. It’s fair to say that, with the opening of every new packet of prints that arrived from the processor in those days, I spent more time cursing the smotheringly narrow limits of my light-leaky box and its take-it-or-leave-it settings than I spent cheering the results as some kind of creative breakthrough. I knew what real cameras could do. My father had a real camera. I had a toy, a toy which would betray my best efforts at breathtaking captures pretty much at will.

I didn’t feel avant-garde. I didn’t feel edgy.

I felt like I wanted a real camera.

Turns out that the manufacturers of my Imperial Mark XII, along with the Holga, the Diana, and other constellations in the lomo firmament, eventually came to the same conclusion. Many of their cheap products were made in the underdeveloped economies of iron-curtain countries.They cranked these babies out with the chief object of making a quick buck on undemanding first-time buyers and children. There was no attempt to market these clunkers as serious instruments; they were the fixed-focus, plastic-lensed equivalent of a bootlegged Dylan album taped off the mixer board. Eventually, these companies went on to other ways of separating the rubes from their rubles.

Now factor in the effect of time, nostalgia and (wait for it) ironic marketing. In the beginning of the digital age, photography arrives at a crossroads. Film is being challenged, if not falling under actual attack. Photography seems, to some, to have surrendered to a soulless technology rather than the “warm”, “human”, “hands-on” feel of analog picture-making. And as for the black arts of post-processing, the digital darkroom begins to be demonized only slightly less than the clubbing of baby seals. The unexpected, the unforseeable, the random begins to be attractive, simply because it spits in the eye of all this robo-gearhead slide toward pixels and light sensors.

A longing for a simpler time is observed among the young, who long to dress in forty-year old clothes and who regard vinyl records as more “authentic” than digital audio, not in spite of the scratches, but because of them. Film photography and its worst accidental artifacts becomes “retro” product, to be marketed through trendy boutiques and vintage stores. The sales message: anyone can take a picture (true, actually). The box isn’t important (less true). None of it’s important (outright lie). Shoot from the hip! Look, it made a weird rainbow streak on the picture, isn’t that cool?

Cool at a premium cost, as well. Cameras that went for $5.00 as toys in the ’60’s are now topping $100.00 for the same optics and defects in 2012, with one principal, cynical difference; in the newly produced cameras, the optical defects are being engineered in on purpose, so that every frame comes saturated not only with garish color but attitude as well. Every click produces a tic. This kind of salesmanship makes Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans seem absolutely honorable by comparison.

Tolerance disclaimer: can great art be created with a rudimentary tool? ABSOLUTELY. Cave dwellers made wheels good enough to move their carts to market well before Sears Craftsman came on the scene. I can make a sort of painting using dried sticks, but somehow I suspect that a supple, tapered brush gives me more fine-tuned control. In the field of combat, I can open someone’s airway with the shaft of a Bic pen (see your favorite M*A*S*H* re-run) but writing instruments are not, typically, the tool of choice in the operating rooms at the Mayo. We don’t use sealing wax to send love letters anymore, we don’t take the family horse on a Sunday jaunt to the county seat, and we don’t eat peas off a knife. Of course we could. But what is our motivation to do so?

The historic arc of photography bends toward technical development, not fallback. As soon as glass plates were developed, their limits implied the need for film. Once film first froze movement, we needed it to do it faster. No sooner had pinhole apertures allowed a picture to be crudely focused than the market cried out for dedicated glass to refine those pictures. And while many were just getting over the novelty of recording events in monochrome, some dreamed of harnessing all the shades in the rainbow.

Tolerance disclaimer #2: the only reason to use a technique or system is if it gives you the pictures you want. Once your dreams exceed the limits of that medium, however, it’s time to seek a better system. Prevailing over the limits of your medium because that’s all there is can be noble. However, there is no artistic triumph in deliberately using bad equipment to take great pictures. Lomo cameras may entice people to begin shooting, then move on once they outgrow the warps, distortions and flares that these toys produce. Thus the trend will at least have given them time to experiment and master the basics. But for the most part, for me,there are already far too many obstacles to making good pictures to allow the camera itself to be one of them.

Even in the name of cool.

Thoughts?