LP 101

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST FREEING OF TIMES FOR PHOTOGRAPHY occurred about half-way through my childhood, and it made its biggest impact on me as rock music entered its own first great age. In the mid-1960’s, the cover art for record albums finally became untethered from the contents on the discs, so instead of merely being billboards for the music that lay within the package, photographs for popular releases became free to be created purely under their own aesthetic. The impact of Pop Art and the avant-garde, which was already playing out on the fronts of weekly magazines and advertising campaigns of the day, finally made its way to “the kids'” tunes via the covers of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Axis: Bold As Love, Disraeli Gears and dozens of other iconic albums. The images ranged from solarized color to fisheyes to collage, but one thing was true of them all. As art, they were about themselves, and themselves only.

The great thing about the recent return of the vinyl album is that the rangy 12-inch canvas that was lost to the music world during the cassette and CD eras has finally come back, with artists once again designing visions that define only the work itself, rather than the record’s musical content. It’s allowed a new generation of artists to enroll in what could be called “LP 101”, or the art of getting attention. In too many cases, of course, the covers of albums were of far greater artistic value than the tunes inside, something we sadly discovered after slipping off the shrink wrap and dropping the needle. Even so, the entire movement inspired Baby Photog Me to stop looking for alibis for my own “outlier” visions. A photograph did not have to be anchored to reality! Or better yet, it could be tied to my own, personal reality, something which did not have to be explained or excused, but which merely was.

I don’t know where images like this come from. I never have. The intoxicating thing about them is that there is less delay and fuss between their first popping into my head and eventually landing in my camera. The cover designers of the ’60’s had to urge and conjure their heads off with film-based, pre-computer tech to realize their mad visions. Who knows how close the results were to their original brainstorms? Hey, you work in the world you have. All the same, having lived in both times, I’m grateful for the tools I have at hand now, when the distance between a dream and a deed is measured in inches instead of miles.

Speaking of “Miles”, have you seen that cover for Bitches Brew? Outtasite.

TWIN-AXIS ACCESS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY TIME I PHOTOGRAPH BIRDS, I lament the fact that I started in at it so late in life. Indeed, if I had not married a birdwatcher, I might never have strayed into wildlife work to any degree. Just being in the moment as I peer into the very special domains of living creatures has enriched my life. Being able to enrich the lives of others with what I capture from that experience has proven a much more random thing. That is to say, since I started year after others did, I may not live long enough to get really good at the whole thing. Sigh.

Bird shooting is really a double quest, a twin-axis access. Finding the bird, the first axis, is one thing. Finding a reliable way to record them is the second axis, and getting the two tracks to intersect perfectly is not a project for the faint of heart.

My aim was to render a sharp close-up of a heron behind some decorative pond clutter. Auto-focus, however, had other ideas.

With me, focus is a bigger issue than any other shooting consideration. Entering the world of birds as I did with a modestly priced “superzoom” rather than a dedicated (and far pricier) telephoto, I was exhilarated that, with the ridiculous reach of such cameras, I could suddenly get at least some pictures that had historically been the stuff of fantasy. However, just bringing the birds closer was only the first part of the challenge. Many superzooms (and some upscale telephotos) struggle to nail autofocus quickly enough to register bird shots sharply, and much of this problem is exacerbated by the subject’s surroundings. A single blade of grass interposed between your target and your lens can mean a tack-sharp picture of that blade of grass, backed up by a completely blurred bird (see embarrassing example above). Thus, shooting birds in a dense thicket or tree can make it nearly impossible to isolate your subject, resulting in more spoiled shots than my Irish temperament can comfortably endure. I’d like to say that images like the one shown here are rare in my portfolio, but I’d be lying through my tightly gritted teeth.

Of course, some bird photogs are expert in going the other way, and opting for completely manual focus. This, over the span of the unavoidable learning curve, will mean even more missed shots, given the little darlings’ tendency to dart about suddenly. Even when using a tripod to help minimize camera shake at longer focal lengths, nailing focus manually takes a lot of practice, the result being that most shooters would rather swallow bleach than rely on it, but, hey, different strokes and all that. As is the case in almost all types of camera optics, lenses which have the fastest and most responsive rates of precision in auto-focus modes can only be had by laying out serious dollars. This is one of the last barriers to a truly inclusive world for all photographers, and needs to be addressed. It shouldn’t cost thousands to make a beautiful picture, and more and more of photographic tech is all about addressing that issue. Alas, long-range, autofocus-dependent wildlife work is one area where the playing field sorely needs to be leveled. We ought to be able to easily show what we see.

OUT AND ABOUT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS ARE NOT MERELY RECORDS OF WHAT THINGS LOOKED LIKE: they are also echo chambers of who we were, what we incorporated into our lives, what we aspired to. The daily objects, the cultural “set design” of our lives sometimes survives outside their original era of dominance, and thus become unanchored, strange, lacking a backstory. Look at that thing. Imagine having one of those. What were they even for? Who were the people who used them? How do ya work it?

Among many other things that were designed to define their owners, or at least distinguish them from each other, automobiles may rank as some of the most personal. Their power, as symbols of having “made it” in some material measure, seems to have peaked between the 1920’s, when owning one first became an attainable dream for the many, and the 1970’s, when safety and economy concerns began to change the very idea of auto design, making more and more of them matter less and less. And somewhere, in that wondrous stretch of dream farming, came this car.

This 1949 Packard Series 23 Club Sedan seems to us more than merely a means to get from point “A” to point “B”: it’s also about the pleasure, the luxury of getting there. It’s a machine that pre-dates mechanized car washes, with small armies of Dads and apprentices caressing its every curve with chamois and newspaper after hosing it off in the driveway on a Saturday, the object being to ready it for dates on Saturday nights and family drives, to nowhere in particular, on Sundays, as if the very act of sitting in the thing were a destination all its own. It’s thick, heavy….substantial. Its interior appointments go beyond upholstery, resembling the coachwork of the recently-bygone age of horse-drawn elegance. Its engine, blissfully heedless of the environment, is a small factory of roaring power, a beast barely contained within a heaving heart of sheet metal and chrome. It’s grand and noisy and massive and garish and hideously unsafe and, now untethered from our everyday experience, something of a dream machine.

How could you see this thing in someone’s driveway, as I recently did, and not stop, not try to tell its story, not attempt to convey its force? Photographs are never, ever mere records. When we make an effort to craft them, they are portals, sneak peeks into the used-to-be’s that are on the way to becoming the never-was’es, and curating that process is a privilege.

MULTIPLE RECKONINGS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CERTAINLY SINCE THE DAWN OF DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY, and, with it, the fall of the last economic barrier to the making of many, many pictures, my urge to document simply everything that comes into my daily experience is stronger than at any time in my life. In short, I can afford to make many more attempts to document my journey through life than was even thinkable in the film-dominant age of my youth.

This means that I wind up recording much more of the world, and, accordingly, preserving more from its ever-changing churn of events. That fact came roaring home to me the other day when I was looking at some shots from a walking tour of Portland, Oregon that I took in 2018. One of the then-constant sights within the city’s South Park Blocks district was George Fite Waters’ statue of Abraham Lincoln, and, in happening upon it, it seemed like a no-brainer to take a quick snap of it. In reviewing the image, I idly wondered just how many public statues of the 16th president had actually been produced in the 163 years since his death. Turns out he may be the most memorialized figure in American history, with sculptures in over thirty American cities as well as carved effigies in Mexico, England, Norway, Scotland and even Russia (where he is depicted shaking hands with the Tsar…you may want to fact-check that event). Waters’ statue is perfectly average in every respect, except for the fact that, since I last viewed it, it just isn’t there anymore.

Apparently a particularly boisterous 2020 protest on the annual Indigenous Peoples’ Day Of Rage resulted in the toppling of not only the Lincoln statue but a marble depiction of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Rider days, with the result that both works are presently in a protective suspended state. Of course, what with all the tortured re-evaluations of the American Civil War seen in recent seasons, it seems consistent that Honest Abe himself remains as controversial as when he walked among us. At this writing the mayor of Sandy, Oregon still has an offer on the table to host both statues in his town, but the entire issue remains in limbo. Which allows me to circle back to my original point: nothing could be easier in the digital age but shooting any and everything that catches your fancy, for any reason. You don’t even have to have an opinion on whether something should be. The mere fact that it is, as well as the knowledge that, at a moment’s notice, it might no longer be, is enough to merit a picture. Snap away.

TROUBLE CHILD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

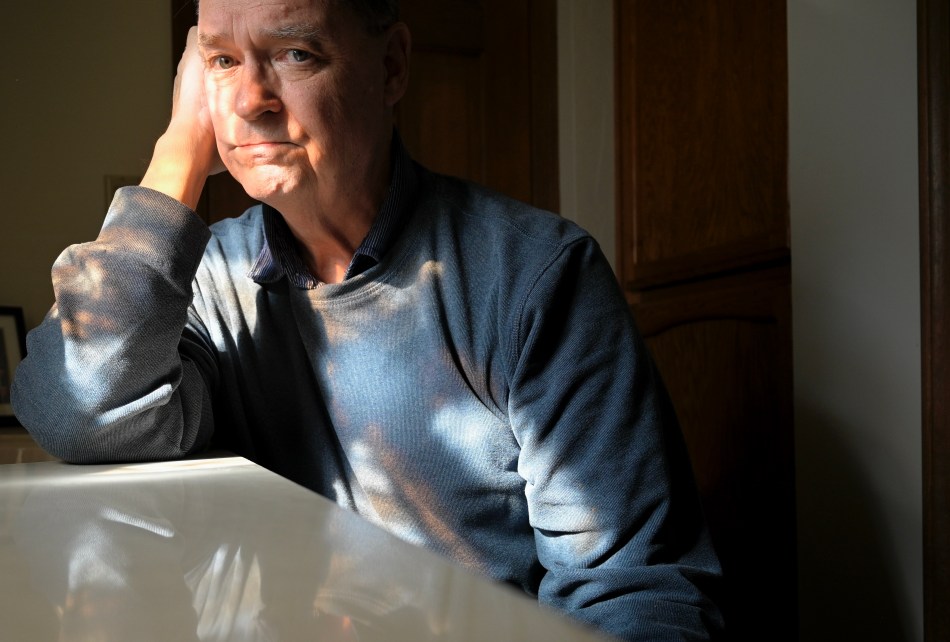

AS I LIMP PAST “GO” AND COLLECT $200 at the turn of another birthday this week, I have to admit that I’m having trouble with the ongoing tradition of taking a semi-formal self-portrait to mark the occasion. I can usually manage to make a flattering image of nearly anyone I photograph, but, this year, I am experiencing a distinct challenge finding something in my own face that I like, or want to look at.

I do about as many random, quick “selfies” as the next guy during the balance of each year, but, as February approaches, I try to sit myself down and discover something, anything that is new, deeper, more nuanced about this grizzled old mug that, by my 70’s, I have often looked at but maybe not always seen. And this year, it’s proving to be a substantially tougher task.

“I AM smiling. Sorta…”

To be clear, I’m not seriously dismayed by the encroachment of wrinkles, the thinning of hair, even a mini-jowl or two, which I more or less consider the price of playing poker. I don’t mind looking as if I’ve been around a while, because I have. But, this year, the wear and tear is registering on some higher level. There have been losses. Some rough grinds. A few stiff tests. So far, a fairly average grocery list of effects typical to the aging male, right? But, for some reason, the face that I see coming back from my trial images seems more grim, sadder, resigned to a life that might translate loosely as “less”. And so, since I usually share the final portrait with friends and family, I “face” a choice between faking some kind of benign bravery (the better for public consumption), or showing what I am truly going through.

Of course, in some very real sense, I need to get over myself.

The importance of the entire exercise is largely in my head: the world at large is not waiting breathlessly for the results, and the entire project could easily be skipped without notice. As a photographer, however, I’m both fascinated and horrified by the visual evidence of the toll of time, and I don’t see how I can claim to be an honest broker of reality and yet turn away when the view gets a bit too close for comfort. One thing’s for sure: merely saying “Cheese” ain’t gonna get it.

MEANWHILE, OVER IN THE SAME PICTURE

Wide-angles give you the opportunity to tell big stories….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ME, THE PHRASE F.O.M.O. (Fear Of Missing Out) is a prescription for a wide focal length. In capturing a scene, I’d much rather choose a field of vision that includes too much information as too little.

Compact tales…

This ragtag little news sheet began nearly a dozen years ago when my go-to lens was more typically a 50mm prime, so much so that its ability to render objects like the “normal” function of the human eye inspired the blog’s name, The Normal Eye, along with a similarly titled photo collection. The belief was that the “nifty fifty” was the ideal street lens, and, given my preference for that kind of work at the time, it seemed like the signature glass for me. And so it was, for a while. However, increased work in the narrow streets of lower Manhattan and various densely crowded bazaars since then have given me fresh respect for fairly wide lenses, with a mid-1970’s-vintage Nikon 24mm f/2.8 as my present default, or as close to a “desert island” optic as I’m likely to get.

…and even micro-narratives.

In shooting really wide, I often start with a master shot, delivering a general, large story, and discover, upon later review, that there are actually several different stories lurking within that massive trove of information. In the topmost shot here, for example, I fell in love with a classic house and its surrounding grounds, and so wanted nearly all of that narrative in a single frame. And yet, because I had all that data from which to select, I also could see the wisdom in cropping to a higher front-of-house shot that excluded the woodsy atmosphere (the middle shot here) as well as much tighter emphasis on the guest room / office / enclosed porch on the side (the third image). The 24 had given me a master shot that was sharp and color-true from corner to corner, so that, not only was there lots of “stuff” in the frame, none of it was exaggerated in aspect or angle, but rather as “normal” looking as anything shot with a 35, 50 or 85. The wide-angle, in essence, had given me what the editor in me appreciated most: choices.

In reviewing this two-year-old shot this week, I was reminded that reaching an enhanced comfort level with a given tool in your kit is every bit as important as owning every lens in the catalog. We all learn to shoot with whatever we have on hand, but shooting with what you love, with what makes your work that much more reflexive or instinctual….well, it doesn’t get much better than that.

ABOUT TO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GIVE A KID ENOUGH CHRISTMASES ON HIS BELT, and he will probably confess that, in many years, the sweet anticipation of Santa’s arrival far outstripped the enjoyment of what eventually showed under the tree. Photographers understand this feeling of limitless potential. It may, actually be the lure that keeps them going back into the breech again and again. Next time, we say. Tomorrow, we assure ourselves. The picture I’m about to make is the one.

That intoxicating appeal of possibility is, I am sure, what’s kept me coming back every new shooting day of my life, the idea that my eye may just be about to execute will redeem me. Justify the time. Excuse the expense. More properly, validate my hope that I can actually do this. That tension-tinged-with-faith is what governs every artistic enterprise, and, for photogs, the approach of yet one more chance to make things right between eye and machine is ever keen, ever new.

New morning: Monterey Bay, 9:42am, October 25, 2010.

Photographers can be led astray of course, since their craft involves devices, and we can be fooled into believing that the magic is in the box, and that, the more sophisticated or expensive the box, the better the output. But everyone who’s made bad pictures with good gear knows this for the fable that it is. The magic originates in the heart, and, with good luck, is at least partly imparted to the box. The difference between “damn, so close!” and “that’s the one” is often measured in fractions of inches, pieces of seconds….but, boy howdy, when we do hit that wave and not only survive it but ride it, it is so worth the price of admission.

That’s why some of my favorite images (like the one seen above) are tied most closely to the feeling that today will be different, and which tend to be the first pictures of a given day. In rifling through piles of old pics, I can always spot these shots. They stamped a little something extra onto my soul, because they got the day off on a good foot, convincing me that I could spend the entire day piling one success on top of another. Some days, of course, the first pictures of the day merely illustrate how very far my journey really is going to be. But even at those moments, I tell myself, I am just minutes from turning things around.

CLUES, NOT DATA

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LONG BEFORE I HEARD THE LOFTY TERM VERNACULAR PHOTOGRAPHY, I collected examples of it. That is, I occasionally bought snapshots from junk stores taken by people I never met, typically without context or notations, their story-telling power limited to whatever actually made it into the picture. Unlike the museum curators and heavy thinkers, however, I didn’t make a distinction between “photos” and “art photography”, and so I never saw the images of anonymous or amateur shooters as “different from” or less than any other kind of picture. Offering no data but only clues, these snaps often spoke to me more clearly than so-called “professional work”.

Let us look upon an example.

The little girls seen here were captured by an unknown photographer somewhere in southern Ohio in the late 1930’s. The print quality and tonal range suggest a professional portrait artist. The image appears to be an intentional group portrait of a kind of kiddie percussion orchestra, equipped with xylophones, trap drums, and triangles, the girls turned out in full costume. The image was likely replicated thousands of times across the country with millions more children at the forward edge of their lives. Without knowing their names or what may have occurred in their lives afterward, without a word of background detail, we can practically feel their innocence, their hope, the way they saw themselves and, in turn, were seen in the first third of the American Twentieth Century.

Ahead. at least for some, lay another World War, marriages, children of their own, random triumphs and tragedies, and the scattering to the winds of lives that are, for this one instant, wound tightly around each other. There is so much we will never be told by this image, but, regardless of his or her anonymity, the photographer has here rendered a document that can teach us volumes about ourselves as humans, and thus must be a work of art, whether or not it ever hangs in a gallery or inspires lofty monographs by curators. To look into these girls’ faces is to look into every child’s face, and that transmission of immortality frees us from time, conveying something universal, eternal. It expresses the spectacular in the vernacular.

THE PERSISTENCE OF PRESENCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

REVOLUTIONS IN TECHNOLOGY ARE CYCLICAL IN NATURE, in that, in ushering in the transition from one era to the next, they also create an entry door for future revolutions, to one day facilitate in the unseating of the age that is currently unseating something else. We see discoveries tear free from past versions of themselves, even as they guarantee that they themselves will be rendered obsolete. The loop is perfect and consistent.

The history of the railroad is the tale of worlds being annihilated or repurposed, of distance and time being shattered in favor of new means of measuring both. If trains were already completely obsolete, it would be necessary to erect monuments to their once-great power, but, as it is, their fade has been gradual enough that the infrastructure of the railways themselves serve as their own headstones. We can only imagine the true muscle they once flexed across the globe, but they are also in enough daily use to serve as miniature museums to their former glory.

The depot seen here was erected in 1879 in Pickerington, Ohio, the same year the Toledo and Ohio rail line first sliced a diagonal across the town. The city, permanently frozen in size as a small farm village, never required a bigger version of the building, which is only slightly larger than a standard boxcar. One historian has noted that the architecture of such places was little more than an echo of the railroad itself, parallel to the tracks and low-profile in both shape and height. One thing seems certain about this particular depot, and that’s that it helped usher in its own obsolescence, when a local named D.B. Taylor took delivery of the first automobile registered in the town shortly after 1900. By 1956, local train service to Pickerington slowed to a trickle, then winked out completely. The station was restored in 1975 by a man named Grunewald, whose family still retains ownership, landing the building a prized berth on the National Registry of Historic Places.

I have visited Pickerington dozens of times over the years, and each time, I shoot the depot all over again, somehow seeing some small something different in it each time. Good weather and bad, fancy cameras or plain, film or digital, wide-angle, macro or soft focus lenses (like the Lensbaby Velvet 28 used here), I can’t resist having one more go. I suppose I’m actually photographing the different persons I have been over a lifetime, and so, even when the village is out of my way on a given trip, I drive to “Picktown” to assure myself that something of value from the past, however drab or simple, has been allowed to remain, to instruct, to educate, and to fill wandering man-boys’ heads with dreams of riding the rails.

JUMP OFF THE TOUR BUS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE COUNTRY’S VARIOUS CHAMBERS OF COMMERCE SPEND MILLIONS burnishing their respective cities’ reps for the sake of prospective tourists, designating themselves as dream destinations, peerless attractions, or The Birthplace Of The Turnip, whatever. They spiff up their resumes in mountains of brochures, travel guides, scheduled tours, festivals, anything to attract visitors and give them a seamless, sunshiny travel experience. All well and good. However, in photographing these places, it might be a good idea to seek the places that every other shooter hasn’t already, well, shot to death.

Sure, go see the official version of Our Town, USA. Take in the ruins, the pioneer memorial, the freedom plaza, the giant ball of twine, etc, etc. But also give yourself some alone time off the beaten path. I’m not suggesting that your spend your entire stay in the rough side of town, but maybe the earlier versions of it, “the town we lived in before we were really a town”. The parts not designated for significant upgrades or “urban renewal”. And, yes, occasionally, “the other side of the tracks”. The places where a quiet, improvised pride of place and home remain a bit frozen in place, almost immune from the passage of time. The above view, from an older residential sector of Flagstaff, Arizona, well beyond the tonier and busier shopping district, is an example of an area where such discoveries may be made.

Of course, city planners take great pains to “rescue” some such neighborhoods, designating them “Oldtowns” or some other cute name, which usually signals that almost all of the original flavor has been siphoned away from the areas as they are “restored”, glossed over, marked with historical plaques, or re-paved with charming cobblestone streets and Victorian light fixtures. We’re not talking about those places here, as they are a sanitized, often bloodless version of life, versus life itself. Jumping off the tour bus is a haphazard process, but potentially rewarding, in that older areas can be seen in real use, in real time, aged but still operating, evoking the past but not encasing it in a showcase, with theme restaurants conveniently located nearby. The term “Discover America”, once a motto of the tourism industry, means just that, “discover”, not “replicate”. Photograph appropriately.

JUST YOU AND ME, KID. OR NOT.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS, THERE IS A CONSTANT YIN AND YANG between giving one’s self as many different options in the way of optics and streamlining to very narrow choices in the quest to eliminate clutter and bother. The very fact that dozens of lenses exist on every major manufacturer’s platform is alluring indeed, and it doesn’t take a lot to make the average shooter buy into the idea that the very next hunk of glass they buy will be “the one”, the ultra-precise piece of kit that will make everything make sense and give us flawless results forever. This can lead to closets and bags bursting with specialized lenses that overlap with each other in purpose and results, and it can lead photographers into debt or down a rabbit hole, or both. The other approach, of course, is to do more and more with less and less.

I go through this argument for days ahead of a planned trip, which is where I find myself at this writing. For the next week I will run into a variety of shooting situations, and I have already spent all too much time trying to prepare for them all by packing…what? Will I need a portrait lens? Will my wider lenses accomplish the same thing? Will macro or soft-focus or supple bokeh figure into the mix? How much actual junk do I want to lug through several airports? And, once I arrive, how much of this gross tonnage will I want to carry with me for any extended period? Should I opt for the most choices, or decide that one, maybe two lenses will be more than enough for 99% of the things I’ll want to tackle?

I’ve come close to doing vacations and trips on a single, one-gizmo-does-all lens, most probably my trusty 50mm primes, and yet I still have never actually left home with only a single option in my kit bag. Part of this may be due to the fact that I don’t have enough confidence in my own flexibility, the acumen it takes to make a single lens do what I need it to do in all circumstances. And even though I logically know that many great shooters committed themselves almost solely to single optics, like Cartier-Bresson with his 50 or Avedon with his 80, I seem always to try to give myself an escape route, despite…..despite the fact that, trip after trip, I come back having used one lens predominantly over all the others that I packed along. At this point, all these lenses are not performing the duty of a tool, but instead acting as a kind of Linus’ security blanket. I know this, and yet…

When I force myself to think analytically rather than emotionally, I realize that, as I age, and do more of my work with a limited range of gear options, I worry less and shoot more. And yet. And yet. And yet my pragmatic fears hamper my emotional surety. That’s not a shameful thing, but it is surely the most human thing about being a photographer.

OF TWO (OR MORE) MINDS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE OFTEN WONDERED WHY PABLO PICASSO DIDN’T TRY HIS HAND AT DIRECTING MOVIES, perhaps some time after he decided that painting one part or aspect of a scene at a time was maddeningly inadequate. Y’know, right about the time he started painting women’s faces from two, three, or a half dozen angles at once. When perspective in a single plane was too…confining, when reality seemed more choked and imprisoned within the frame than composed in it. Of course, some artists of his era did, in fact, put down the brush and pick up the motion picture camera (think Man Ray or Jean Cocteau), seeking liberation from the box. Different strokes, as they say in the painting biz.

As a green lad, I had a period of about ten years when I laid down the still camera and shot movie film (not “video”) in search of a more fluid visual language. I eventually came back to the fold, and, indeed, now find it odd to shoot video at all, with notable exceptions. However, some “still” techniques also continue to feel inadequate to my needs. Self-portraits, for example, are often a source of frustration to me. And I do mean “to me”. After all, If someone else tries to capture “me”, I can at least overlook their failure because they really don’t understand their subject. However, when I fail to render “me” in a satisfactory way, where do I lay the blame?

As time goes by, I become more and more convinced that none of us has a representative “look”, one universal template from which we can stamp out consistently recognizable versions of ourselves. We always stray from even our most skilled definitions of who we are, and maybe that’s the beauty of trying to capture ourselves in a camera. It’s the task that can never be completed that’s most tantalizing. It’s the melody we haven’t yet learned to sing that is our siren song, the one thing that keeps renewing our love affair with, our need for art. We can’t lick the problem merely by going full-on Picasso and trying to shove all versions of ourselves into a single shot. Our identity can only be revealed one leaf of the artichoke, or one leaf of the camera shutter, at a time.

MY OWN PRIVATE RETRO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

DULL THINGS ARE BURNISHED BRIGHT BY MEMORY, a thought that occurs to me every time I see an ad for a new optic or camera that is designed to “bring back” the sensation of making images as we did in the analog era. I’m not against such sentiment since it is a waste of energy. Opposing the allure of nostalgia is as pointless as warring against Classic Coke. Things “that once were” take on a thrilling, warm appeal once they’re endangered, and so film photography, and all the elements involved in creating within that format, will continue to occupy its sacred niche, generating new/old products designed to deliver a specific experience in a world in which said experience is no longer dominant.

Having been raised in a film environment, I was all too happy to see its high cost, inconvenience and technical limits head for the history shelf. I will still shoot a roll here and there “on a lark” but I would never again attempt to make my most serious or vital work in that medium. The new breed of retro gear certainly interests the mechanical tinkerer in me, but the serious photographer in me likes the speed and ease of shooting with the latest refinements, not merely tweaking the old ones.

Bistro, January 2, 2024. Shot on full manual with a Lensbaby Velvet 28, f/3.5, ISO 100, 1/125s.

One aspect of analog photography, however, still holds an appeal for me, and that is shooting on full manual. Doing my own focus and exposure gives me the hands-on control that I associate with my best days in film, but with the flexibility and predictability of digital. My own private retro zone is thus something of a hybrid. Film represents to me the risk and bother of an earlier age, but, at the same time, I retain the right of “final cut” in overriding auto functions as I see fit.

To me, having the camera handle a lot of the fuss that used to bedevil the process of composing and exposing a shot is a selling point, just as I value having the last word on the precise method of visualizing a picture. You can keep all the new toys that are designed to replicate the limits and flaws of old camera tech, and you can certainly keep the financial burden of processing film, which has only become more annoying over time. Simply give me the ultimate say on how to approach an image, paired with a camera that ever more instinctively gives me, in the final product, what I saw in my head.

LAYING DOWN A MARKER

Overlooking Downtown Ventura, California, August 6, 2023

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MOST YEAR-END PHOTO COMPILATIONS TEND TO BE boasting boards, a parade of the pictures that show off technical mastery, a collection of “Oh, Wow” shots that act as a kind of resume builder for the makers. Moreover, many such lists are specifically pitched as contests, pitting one person’s skill or eye against all comers. These reviews are fun, but, as year-end reflection sets in, I am tempted to sum up the outgoing year in terms of the pictures in which I was keenly and emotionally invested, rather than those where I “nailed it”, leading me to compile a list of “most ofs” rather than “best ofs”.

Overlooking downtown Ventura, California, August 6, 2023

The shot seen here is not the kind of image that’s instinctively in my wheelhouse, in that landscape work is not where I feel my strongest muse. I do it, and occasionally do it competently, but such pix are never the photographs that I feel say anything profound about me, or the things I care most deeply about. And yet, for 2023, I feel that this image has become more important than what it seems to be, i.e., a bird’s-eye view of a small coastal town in California, because, with any luck, it’s where I’ll be moving soon.

That very fact elevates the picture, at least for me, to more than a nice scene. It now represents an aspiration, an ideal, and the first serious attempt I’ve made to re-boot my daily life in over twenty-five years. Of course, this is a very internal conversation I’m having with myself: to anyone discovering the picture without the backstory, it’s merely a pleasant little photo of a pleasant little town. That is to say that I didn’t say anything universally “wise” in making the shot. In fact, I’d be willing to stipulate that the other hundred or so daily visitors to this overlook on that particular day came away with almost the exact same shot, give or take a few factors. And yet, since photography is, for me, a journey, documenting where I have decided to let that journey take me is important. In the eyes of nearly everyone else, this picture will never rise above the level of “okay”, but, looking back at the whole of 2023 and how it shaped me (and my work), it lays down a marker as a “most of”. And with what’s ahead of me in ’24, I need all the North Stars I can get.

OPEN THE POD BAY DOORS, HAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“ASK THE MAN WHO OWNS ONE”, suggested an ad for Packard automobiles in 1949, the idea being, I guess, that only someone who’d had the personal experience of driving said car could convey the utter delight of it. That slogan ran through my mind the other day when I saw the first image made by a photographer friend using artificial intelligence, an image that prompted me to ask this truly creative artist not what the process felt like, but only the single word, “why?”

Legal disclaimer dept: I guess if you have to insist that you aren’t a luddite you may at least have worried that you might actually be one, so let’s openly stipulate that I am not yet sold or unsold on A.I. as a tool for myself. Instead, let’s try to lay the thing out logistically. Making an A.I. picture entails dictating your terms, i.e., the elements and style for the image you want, into a computer program, then allowing it to sample examples of those features across every photograph it can access to assemble a composite result that satisfies those terms. For example, you could make a list that included instructions, like sunset, red skies, light clouds, rustic barn, scattered sheep on wooded hillside, etc., then view the results within an amazingly short period of time. That’s greatly oversimplified, but, in a nutshell, that’s the gig.

This image is manipulated, for sure. But I’m the one who did the manipulating. Of my own shot.

And so my initial question is, why would I regard this as a creative exercise, any more than I would feel a pride of a sandwich’s “authorship” after shouting my ingredients through the McDonald’s take-out window. Making a photograph is about as personal a thing as I have ever attempted, and the fact that I, myself direct how much ketchup, pickle or lettuce goes into the thing is what makes it mine. A.I. already makes some amazing images, and, for editors or marketers who can now order up anything they can imagine, on budget and on deadline, I see endless applications in the commercial world. But merely envisioning the end product and then submitting your order seems, to me, to be taking one’s hand off the creative steering wheel too completely and way, way too early. It’s like hiring a birth surrogate and then telling your friends that you “had” a baby. Well, no, you didn’t.

The move from photography to A.I. imagery is not like the shift from analog to digital. That was merely a change from one light recording medium to another. And it’s not the same as standard image manipulation, either, because, again, the artist is directly involved in every stage of post-processing. We’re in new territory here. A.I. can’t even be compared to assembly arts like photomontage, because while the final work is pieced together from disparate elements, the combining and arranging are all accomplished by a direct, personal act of assembly. And we don’t even have space here to discuss what A.I. will mean to the idea of “authorship”, which the internet has already shredded into swiss cheese. Right now (the end of 2023, in case you read this later in an archive), it’s an amazing process that generates images. And, as time goes by, the artist will be no doubt be more directly involved in making those images closer, in nature, to actual photographs. But we’re not there yet. Not by a long shot.

TAPS FOR CHRISTMAS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE BEEN LUCKY ENOUGH TO LIVE TO THE AGE OF SEVENTY-ONE before having to type this sentence:

This will be my first Christmas without my mother.

It’s amazing how long my fingers floated frozen over the keyboard getting that said, but I have to filter all the poignant events of this one year through the lens of her having made it through nearly ninety-one of her own. Memories are odd things; they take whatever form best matches our needs. Sometimes she is with me in the recitation of a family saying, complete with the sound of her voice. Other times, she flashes up in front of me unbidden, summoned through some bizarre daisy chain of impressions that can spring from any and everywhere. Bang, she’s here again. Whiff, she’s gone once more.

We were always a family of picture-takers, and so there is ample documentation of her face at every age, from the crib through her “career” as a high-school majorette to her happiest role, that of a wife to my father for over seventy-two years. Sometimes, in this first year in which she has left an empty chair at the table, I can comfort myself with those images, looking directly into her face. Other times, like this entire month of December, I have to make it through by buffering the reality of her absence a little, “seeing” her in the things she loved.

She loved this season, and filled her house with generations of laughs, tears, parties and celebrations, adding more elegant elements to each succeeding Christmas season. And what you see here were her greatest pride, the “regiment” of nutcrackers she had amassed over thirty-plus years. Each had its story: each was attached to its giver in an unbreakable chain of smiles and remembrance.

This year, the troops were finally retired on the family mantel, perhaps after their bugler has quietly rendered “Taps”, replaced by my sister’s collection of angels, a visual cue that the torch has been passed and Christmas is in the hands of yet another trustworthy caretaker. After this emotionally supercharged month, I will gradually go back to the photos, back to making direct eye contact with that unbelievably beautiful and comforting face. But now, I will have, as the song goes, a merry “little” Christmas, looking again on her handiwork, both in the things she created and the people she adored.

It will be enough.

It will have to be.

AN EFFECT IN SEARCH OF A MOTIVE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY HAS NEVER BEEN SATISFIED to act as a mere recorder of, although it has certainly been used as a clinical instrument, charged with documenting the size and texture of things in the “real world”. And as useful as it has been, since its inception, in helping to identify, quantify, catalogue or certify things (think police mug shots or historic events or travel destinations), shooters have never been comfortable with using it just to measure or preserve. Just as painting is innately interpretative, making no real claim to verity, so too photographs are points of departure from what is real….real PLUS, if you like.

Lenses and processes, then, have always been developed to service both the accuracy of documentation and the fancy of imagination. Same tools, different uses. Sometimes we can shoot something a certain way before we know why we would want to even do it, sort of an effect in search of a motive. We can make the picture do this. But why would we? That is to say that no custom gimmick or look is appropriate for every shooting situation. We marvel at the technology that conveys a certain sensation; deciding if it serves the image at hand is another thing entirely.

AS one example, an effect that began as an attempt to tell a more complete story is the panorama. Its beginnings were defined by specialized lenses and cameras that enabled chroniclers to show several thousand military cadets in one shot, or render the complete flow of an entire city block. Over the decades, dozens of techniques have been used to make panos easier to take, with digital tech making shooting them nearly instinctive. Still, the question for the photographer remains, what to do with this unique type of view? How to marry subject matter and system in such a way that both complement each other, rather than being merely novel? The making and processing of the shot seen here, for example, were all done in-camera with a cell phone and a cheap post-processing app, making it easy to follow a momentary impulse and have an acceptable result within minutes. But is anything unique said or amplified with this viewpoint? Is this the best way to display or portray this space? Was that the point?

Filtering reality through our own personal vision requires a unique match of gear and imagination. One cannot perform without the other, but the balance between the two is a delicate dance.

THE MOMENT WHEN THE MASK SLIPS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Lord, what fools these morals be!

William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

ELLIOTT ERWITT, the world’s most widely published freelance photographer, who passed just days ago at the age of ninety-five, served up, in over a half century of work, many proofs of mankind’s folly, but never with Puck’s snooty disdain. For decades, his work displayed our most unguarded moments, the brief instants when the mask of control slips a bit and reveals the vulnerability within. We laughed at his images because they were true; it was easy to identify with the ironic, or strange, or hilarious behavior in the people he snapped because they were us, in all our sloppy and divine imperfection. His was a great eye, and his work was a great gift.

Born Elio Romano Erwitz in France in 1928, Erwitt emigrated to the U.S. while still a child, and was formally educated in picture-making in Los Angeles before moving to New York in 1948, where he chanced to meet the photographic superstars of the day, including Edward Steichen and Robert Capa. By the time he was drafted into the Army in 1951, where he worked as a photographer’s assistant, he already had several published commissions under his belt, and, upon returning stateside, he became a full-time freelancer, taking assignments from the prominent print magazines of the day, from Life to Look to Colliers and well beyond.

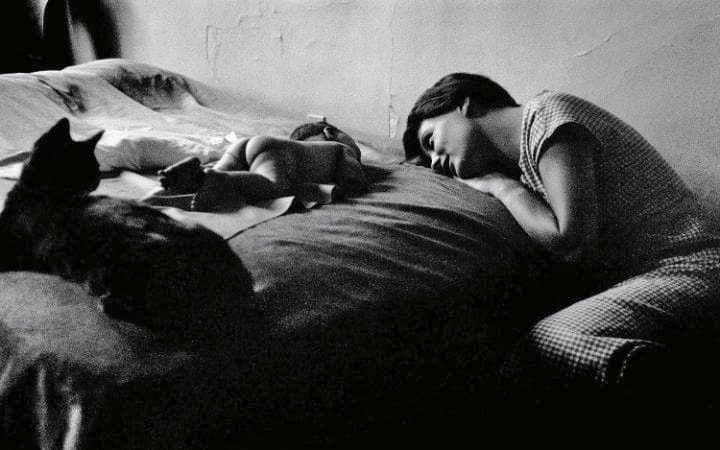

Erwitt’s work became mostly associated with whimsy, eliciting dry chuckles from the candid realities he extracted from his random street work. However, his output was always leavened with more conventional journalism and portraiture, ranging from his moving shot of Jaqueline Kennedy receiving the folded flag from her husband’s coffin to cover images for The Rolling Stones’ Get Your Ya-Yas Out album. One of his most widely circulated pictures, seen above, was a shot of his young wife and his infant daughter staring at each other while a cat looks on disinterestedly. It wasn’t Erwitt-funny, or wry, but it became a permanent part of Edward Steichen’s global curation of images from everyday life, The Family Of Man, which made its debut as both an exhibition and a book in 1955. When I heard of Erwitt’s passing the other day, it was this picture, not his “what fools these mortals be” images, that immediately sprang to mind. It’s eternal, universal, quiet in the way a Mozart adagio is quiet, and true, the kind of legacy any photographer would give his right arm to leave behind: the moment the mask slips, revealing a tender humanity underneath.

WEATHER OR NOT

Instant rainy day: an in-camera white balance tweak designed to simulate shooting under florescent light

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NO SOONER DID PHOTOGRAPHERS SUCCEED in their earliest attempts at trapping light inside a box than they set about to see what kind of light they might prefer on any given day. From the very start, shooters have tried to shape the color and tonal range of their subjects rather than just record the prevailing conditions. To cite one f’rinstance: when I was a youngster, riding my pet bronto to the classroom cave, all sophisticated cameras came with instructions on how to achieve an ideal white balance, the better to either correct for nature’s shortcomings in a certain situation, or sculpt your own look for effect. Half a century later, it’s amazing just how easy such manipulations have become in the digital age.

Same scene, mere seconds beforehand, shot on an “natural light auto” white balance.

Now white balance is simply another dial-up operation, something that can be as easily selected as an aperture or a shutter speed. Suddenly all those screw-on filters and charts are just so much junk in a drawer. It’s amazing how baked-in this kind of convenience has become, removing what used to be a time-consuming calculation not only making it completely instinctual but virtually instantaneous. We are now capable of, if you like, making our own weather ahead of the click.

Like everything else that used to be a pain about photography, the streamlining of white balance has joined many other operations that were obstacles between envisioning and executing a shot. That means greater and greater emphasis on training one’s eye and less time wasted on “I wonder if it will work out?”. All cameras are being designed to anticipate most of the problems involved in making a picture, so that it’s harder every day to take a bad one (although I stubbornly manage to do it, and often). Creating tools which take things like white balance and light metering inside the camera streamlines the entire process of photography. Fewer steps, fewer chances for error, more time for selecting and grabbing your vision.

THE VERY PICTURE OF….ANOTHER PICTURE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I CAN’T BE THE ONLY PERSON WHO HAS EVER SEEN this classic image of photographer Margaret Bourke-White peering over a stainless-steel projection near the top of the Chrysler Building and asked themself, “so who in heck is taking this picture?”

Oh sure, we know the basics of the story. In 1930, The skyscraper’s owners invited the already-renowned MBW to set up her wooden view camera on one of the structure’s eight gleaming eagle’s heads at the 61st floor, and take in what was then an extremely privileged view of Manhattan. The building, not yet quite completed, would eventually top out at 1,046 feet (77 stories) above the pavement, winning one of the city’s most celebrated “skyscraper wars”, cinching its right to Tallest stature by virtue of the gigantic steel spire that served as its crown. Bourke-White, whose studio was then located in Cleveland, had already considered moving to NYC to be nearer her employers at Fortune magazine, and once she ascended to take in the, er, eagle’s-eye view, she decided that the Chrysler itself should be her new HQ, all the better for her to be the two eagles on the corner where she shot, which she nicknamed “Min” and “Bill” after a popular movie of the time.

But who else made the ascent that day, to take a picture of her.. taking a picture?

Introducing the nearly-forgotten Oscar Graubner, Margaret’s full-time darkroom assistant and amateur snapper, who often traveled with Bourke-White on what was, by the early ’30’s, already a global trajectory, a career which would take her from the opening of hydroelectric dams (the first Life magazine cover ever) to photo-essays in the young Soviet Union to, eventually, every major theatre in the European war and the India-Pakistan schism. Graubner was part of what built MBW’s nickname of “Maggie The Indestructible”, and, by chance, snapped the best image of her at work. Strangely, his picture of her doing her thing from the top of the Chrysler has now been viewed many millions of times more than any pictures she actually made herself from up there. The history of photography may be peopled by giants, but it’s punctuated by those who toil in their immense shadows.