GO BACK ONE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I FIRST HEARD THE PHRASE “RUN AND GUN” applied to street photography in a lecture by the great Joe McNally, a lifelong pro and official worldwide Nikon ambassador and the author of superb tutorials like the classic The Moment It Clicks, who used the term to describe the practice of shooting quickly and intuitively with a minimum of fussing about gear and a deliberate intention toward the instinctual. Trained in rapidly-evolving journalistic environments, Joe was every bit as facile in clicking away at a rapid clip as he was in his most prepared and staged images. This means, despite the term’s wording, that “flexible” is a more important trait than “fast”.

When I must shoot a lot of things in a short space of time, as when I am walking alongside my New York-born wife, who definitely has a “Manhattan stride” and is definitely on a time line (usually a brisk one) to get somewhere and do something, I find that I must make many decisions in the moment. This does not merely mean racking up as many shots as I can physically click off and hoping for the best. It comes down to evaluating situations in the moment, trusting my first instinct on what may or may not constitute a worthwhile shot, and at least being prepared to execute without excess delay.

Obviously, at the end of a R&G day, this results in a fairly bumper crop of images, the value of which can not always be seen when upon first view. The certified killers certainly stand out, as do the abject clunkers, but the vast number of shots in between those extremes sometimes take a while to reveal themselves. I myself have built up the habit of looking back on a given shoot at the distance of at least one year, as it erases many of the first judgements you made about the pictures and allows you some objectivity, as if you are evaluating someone else’s photos, which in a very real sense you are.

Upon my earlier reviews of pics taken on a fairly quick walk through Greenpoint, Brooklyn almost exactly a year ago at this writing, this young woman got lost in the shuffle. She had a special quality, but I was uncertain as to my execution, and so moved on to more obvious prize winners. It’s a sucker bet to act as your own photo editor anyway, as your choices are fraught with both bias and bad habit, but waiting a year can make you look at things in a far different way from when you first chose to click the shutter. Of course, some times you decide that your “blue ribbon” entries from that time aren’t quite the miracles you originally thought they were. But, when a smile comes to you from an unexpected place, well, that’s the whole ball game, innit?

GO WES, YOUNG MAN

Straight out of the camera at f/8, 28mm, ISO 100, and 1/400 sec. Standard exposure scheme.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SEVERAL YEARS AGO, WHEN WES ANDERSON FEVER was tearing across the popular culture, there was a mad race among photographers to simulate the director’s hyper-saturated, deliberately unreal color schema, partly as a tribute and partly as a technical challenge for those of us who love tinkering almost as much as we like shooting. Like many such fevers, the mania to be more Wes-like exploded into processing shortcuts and on-line recipes for in-camera sims of scenes from films like Asteroid City, a movie which transforms the starched American Desert into a mega-pastel postcard from the 1950’s. Entire books, like the Accidentally Wes Anderson series of travel images, were created to basically allow anyone to try faking what WA had created organically. We went a little nuts.

Same image “Wes Anderson-ized” with substantial reduction in contrast and a bump in vibrance. Not complicated.

The thing that occurred to me during all this here’s-how-you-do-it mania was how overcomplicated people were making the entire fakery-cum-tribute project. To me, it was not supremely technical to get the “Wes look”, although it did induce me to rethink how to alternatively “mix” things I’d already captured beforehand. To me, most of the effect came down to merely moving left on the contrast slider and moving right on the vibrance one. No major strain, as James Cagney used to say of acting.

Of course, one man’s cool effect is another man’s useless gimmick, and there are many strong opinions about the so-called “flatness” of low-contrast photography, no matter who it intends to salute. That may be why the Just-Like-Wes movement burned out so quickly; it was treating a technique as if it were, by itself, a message. There’s a reason why we stopped going to fairs and carnivals to have ourselves snapped as fake daguerreotypes as we once did in the ’70’s. It’s because a photograph has to be about something beyond just the technique required to make it. Shooting for the effect alone is craft, with no art to flesh it out or deepen it. Your camera, your vision, your choice.

THE FUTURE’S SO BRIGHT…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC TOOLS HAVE FINITE LIVES; they are introduced largely to solve a problem or improve results, and, as they age, can eventually create different problems which, in turn, have to be solved by succeeding technology. Gear thus has a birth, a life and a death, moving from something we need desperately to commonplace practice to antiquity and obsolescence.

One such tool that, in the year 2025, is heading for the scrapheap of history is the loved/hated electronic pop-up flash, which, at this writing, is fast disappearing from new cameras at almost every level of expertise. Once seen as an ingenious miniaturization of the bulky electronic flashes of earlier eras, pop-ups are being deliberately designed out of incoming models, as fundamental rules of how we amplify or disperse auxiliary light in an image have shifted dramatically. Truth be told, the humble pop-up was always the Rodney Dangerfield of flash, in that it “never got no respect” from serious pros, who either mounted more responsive, more controllable units on camera flash shoes or used the pop-up merely as a trigger for off-camera slaves. Pop-ups were never capable of throwing light very far (ten feet was a reach) and, without the means to pivot or customize their angles, they mostly blew super-hot light directly into faces, blowing out detail and obliterating even those shadows the shooter actually liked. This linked them forever to a kind of snapshot. or “light it at any cost” mentality, mostly among amateurs.

And then there was the fact that pop-ups, being in part a mechanical feature, were more prone to failure or breakage than nearly any other component on the camera. The digital age pounded another nail into the pop-up’s coffin as well, making sensors more responsive to a wider dynamic range, lessening the number of shots that would even benefit from spot flash. Finally, as even cell-phone cameras create a balanced exposure through so-called “computational” calculation, flash pictures themselves, except in professional studio situations, are obviated more and more by better camera brains. And, finally, there is the consideration of the sheer space and electronic real estate taken up by a pop-up, space that could be better allocated, as Fstoppers magazine has remarked, “for better screens, faster processors, or improved connectivity.”

Photography has always been about the better mousetrap, and, after more than half a century as a standard feature on cameras the world over, the pop-up flash is just about ready for its final close-up. Some would say it’s the end of an era, but making pictures isn’t about isolated sectors of time, more like a continuous river of upward improvement. Tools are tools until they are impediments, and then, they are gone in a flash.

HORSESHOES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MORE QUIET EXITS from the average photographer’s toolbox over the last twenty years has been that of the once-ubiquitous tripod, that rigid testimony to the fact that here, ladies and gentlemen, was a serious shooter, someone dedicated to precision and accuracy. The anti-shake and image stabilization programs that are now incorporated into even the most modest cameras have largely relegated the “three-legged-spider”, as I call it, to the closet. The devices still command a multi-million dollar industry and are certainly in no danger of winking out of existence, but the everyday shooter can do very well without them much more of the time. That’s not a judgement, merely an observation of how once-crucial gear becomes a luxury or exception, like light meters or flash guns.

Of course, spending lots of time with birders, I still see folks carting their cameras around atop the things, using them mostly to stabilize shots that are zoomed out all the way and which would otherwise pose the problem of magnified body shake. But my own use of tripods, back when I regularly used them, was not for nature work but for urban nightscapes, where light would be a premium and extended handheld exposures would guarantee an unsteady result.

This 2017 shot of the skyline of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for example, would have been impossible to do handheld, back then, especially since it was taken from the top of nearby Mount Washington, with evening winds buffeting me around even as the icy temperatures made me shiver. Shooting without a tripod would have meant going wide-open, to about f/2, to allow for maximum light intake in a brief exposure, as well as jacking up the ISO to untold heights, which, in shooting a dark sky, would have invited in a ton of noise and rendered the building lights as bleary blobs. Today, with a full-frame mirrorless sensor, I just might be able to shoot the thing hand-held, but getting it this clean would still be more luck than genius.

Things are essential until the world deems them not so. We don’t buy a lot of vacuum tubes and horseshoes anymore, and so living a life that still incorporates them centers more on nostalgia than functionality. Every once in a while, hauling around a 600mm telephoto while stalking a tiny bushtit may make me long for the physical comfort of a three-legged spider, but I value being able to work faster with less fuss, a state to which every photographer aspires.

STRONG AT THE CENTER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EDWARD STEICHEN’S MAJESTIC PHOTO ESSAY The Family Of Man, which was first mounted in 1955 at MOMA as a curated exhibit and was then captured within one of the most essential reference books in all of photography, remains a essential document on the sameness and uniformity of human behavior across all social, ethnic and financial demarcations. It actually gives reality to the old saw that “we are all the same”, showing mankind in peace, love, war, ritual, youth, old age, birth, death and hope. It is a miracle project which I urge you to add to your collection.

One of the key elements of FOM for me is its depiction of the universal essence of motherhood. All the anxiety, risk, and courage displayed by all women in all corners of the world, all of them wanting to endure, to protect their children, to hand something on to the next generation of mothers. In my own halting way, I am always looking to capture some small something of the unique energy of mothers. It informs my street work in a way no other subject does. And, is often the case with candid work, you find more little miracles the harder you look for them.

And, sometimes, you get a gift.

Three years ago, during an ordinary visit to my wife’s son and his family, I had the occasion to observe both her and her daughter-in-law, gathered within a few feet of each other, each submerged within quiet worlds of their own making, Marian musing over a sinkful of dishes, Erin taking a breath between Momtasks. Both women possess faces which both reveal and conceal, making them irresistible for frequent visits from my camera. I know them both well and yet could never really, fully know them at all, making the next images of them magical with potential.

Perhaps that next shot, goes the delusion, will be the one that explains everything. Of course, this can never be the case, and yet I continue to click away into infinity in vain pursuit of the day when, as Frank Zappa used to say, The Great Oracle Has It All Psyched Out. Steichen’s Family Of Man is an exploration into what all of us share across our collective humanity. But you don’t have to wander the globe to see those commonalities. Sometimes, all you have to do is look across a kitchen.

I WAS JUST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD ANYWAY…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CROOKS AREN’T THE ONLY PEOPLE WHO RETURN TO THE SCENE OF THE CRIME. Photographers have the same neurotic habit of going back to the place where things went wrong. Only, instead of a “crime”, it’s the scene of a picture that we (a) loused up the first time (b) loused up the second time, (c) might look better with a different camera/exposure/lens or (d) is just some infernal, unsatisfiable itch that we must scratch or go crazy.

This building is one such place. I don’t know why it is filed in my fevered brain under “unfinished business”, but it is.

This apartment block is just one street away from the home of a dear friend in central Los Angeles, so I have probably made the short pilgrimage to it for at at least ten years’ worth of visits. Part of its attraction is that it’s one of the only original Art Deco structures left in the neighborhood. Another part of it is the utter simplicity of its design, as is its clean teal tone. I’ve been snapping it for so long now that a complete folder of my collected shots of it could easily serve as a time-line on my own development as a photographer, as I’ve taken a crack at it through every phase, fad and infatuation I’ve endured over those ten years.

I’ve taken it with wide-angles and telephotos, primes manual lenses and fully automatic exposure. I’ve given it the lo-fi treatment with both cheap plastic and pricey Lensbaby art lenses. I’ve done full-on frontal shots of the entire building, distorted fisheye angles from the corners and sides, time exposures just after sunset with its windows all aglow and, as seen here as vertical slices designed to abstract it to pure shape. I think I’m done. However, I’ve said that many times before.

It’s frustrating enough to get a single pass at a place or subject, such as a snap of a tourist location you’ll never re-visit. It’s frustrating in a different way to have unlimited access to something that you can’t quite seem to nail, not matter how many swings you take. I was not blessed with a natural bent toward humility. However, thanks to photography, it’s closer to second nature for me. If I live long enough, I might just finish growing up. Or finally get The Picture of this wretched building.

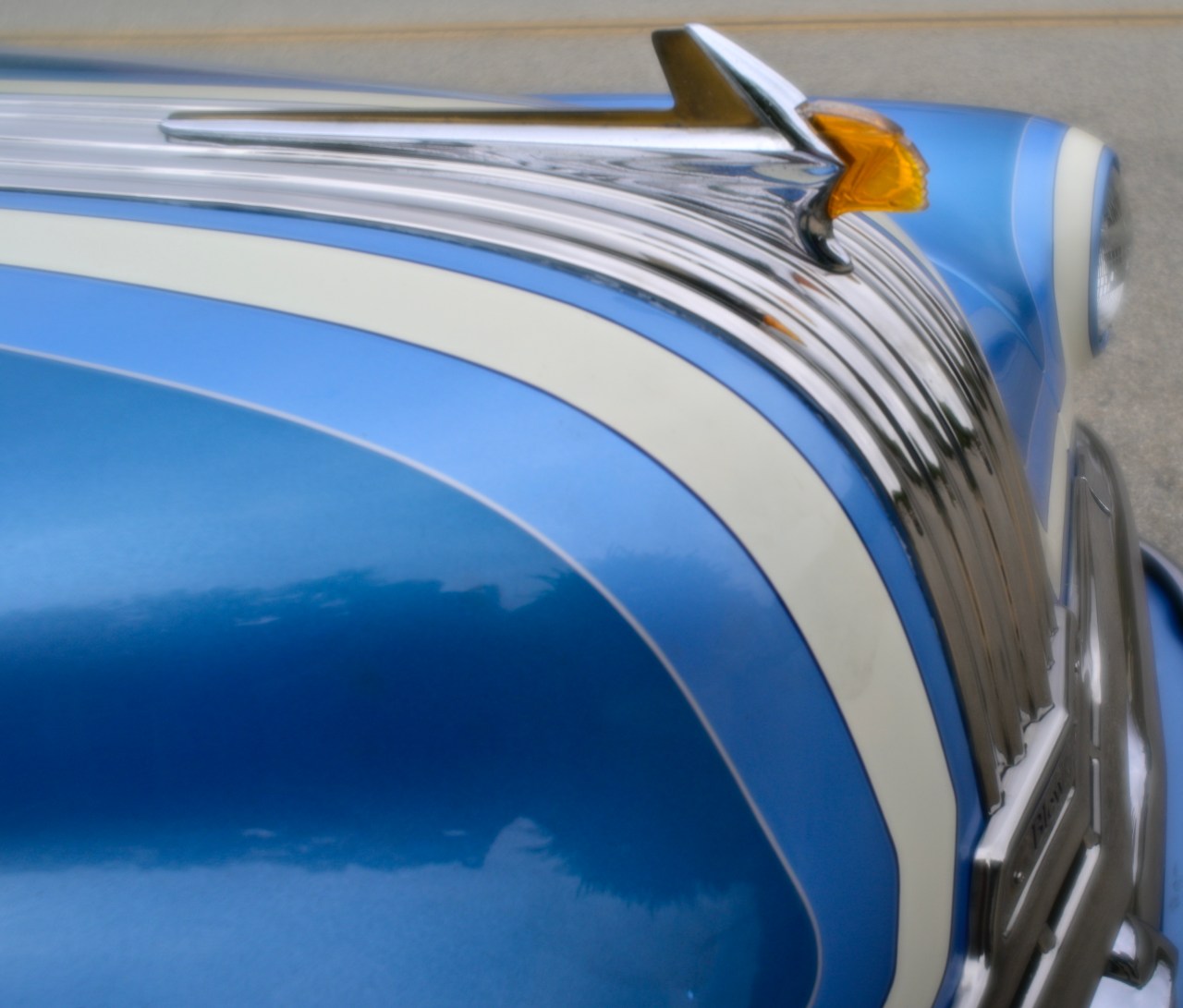

Dream Machines

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AT THIS WRITING, I HAVE JUST COMPLETED A LONG WEEKEND characterized by three really early morning treks to three consecutive birdwatching sites, a brutal trifecta of trudging and toil that has left me footsore and bent over, worn raw from bad shoes and the nagging shoulder weight of a five-pound telephoto. The weather, as is often the case along the Pacific coast, was iffy, which meant that the percentage of keeper shots plunged even further below my usually sorry harvest. It will take me another three days to sift through the raw takings, alternatively cursing the blown opportunities and over-celebrating the luck-outs. And so, as an antidote to that very long march, I have plunged into the only pure fun I gleaned during the entire ordeal.

Spoiler alert: it’s not a picture of a bird.

Well, in its day, it certainly soared like one. And, for me, limping several blocks from my apartment to visually make love to a supreme achievement in pure, seductive design, as an emotional balm for my aching’ dogs, it definitely made my heart take wing. I don’t know where this vintage 1940’s Pontiac Torpedo came from. The home where it was parked is, regularly, home to owners of elegant machines from bygone eras, usually of the pimp-my-ride-low-rider variety. One thing I do know is that none of these dream machines hang around for more than a few days. That made it Pilgrimage Time for me and my Lensbaby Velvet 28, which, shot nearly wide open, wraps its subjects in a dreamy haze that encases the focused image without blurring it. Watch the over-exposure on the chrome highlights, buy yourself some insurance with the use of focus peaking, and, voila, an express ticket to Hotrod Heaven.

I feel a little better equipped now to wade through three days’ worth of “maybe” images of birds while my knees and shoulder mend. I needed a quick dose of control, or at least the illusion of being able to make a picture instead of hoping I captured one. The fever’s broken now. But oh, what a delightful delirium!

DAYCARE CASUAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE THINGS THAT DISTINGUISHES THE VIBE in small towns is the variable definition of what constitutes “public space”. Where do people actually gather? Where are social interactions transacted? What is the familiar hang, the “everyone goes there?” Photographers who find themselves even temporarily out of their own neighborhood elements are constantly searching for the answer to the “where it’s at” question in the places they’re cruising through.

I’ve never seen a puzzle and game play space inside a Starbucks, or, for that matter, inside the average courthouse, city hall or bar. But inside a coffee house in the small coastal town of Morro Bay, California, it’s obvious that whole families, kids and dads and moms, are frequent players, stopping by for a cappuccino or espresso, a bun or croissant, and….a few chill moments with a jigsaw puzzle. The coolest part about encountering this mother-and-child team in the joint was how unremarkable they seemed. The local feel for this cafe was more than “everyone is welcome”. It was all the way to “whatever you need”. And then some.

No other customers in the shoppe seemed to acknowledge this micro daycare center activity; it was obviously just part of the daily rhythm, what made the town the town. I was only about eight feet away from the pair when I snapped this, a single-frame go-for-broke frame. I was so afraid of either making them feel as if they had to pose, or, worse, feel violated by my presence. But there was just so much life, real life, in the scene. I’m glad I had my shot.

lower case G’s

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE HUMAN VANITY WITH WHICH ALL PHOTOGRAPHERS, much like disposable cameras, come “pre-loaded” would have our audiences believe that all our work is the product of meticulous, deliberate planning, a “vision” that flows, fully formed, from our marvelous minds through the lens. Of course, anyone who’s taken the requisite number of rotten pictures needed to attain any skill whatever knows that this is a fantasy.

The raw fact is that many, many of our most wonderful photographic notions die a-borning. Either they come up short because we don’t possess enough skill to execute them or they fall prey to a thousand random factors that occur in the instant an exposure is made. And while we are more than willing to parade our successes as if they are de rigueur, something that happens effortlessly everytime we trip a shutter, we don’t tout the many happy accidents that sometimes work out better than what we started out to achieve. We aim at upper-case “Greatness” and, instead, get lower-case “gifts” from the Gods Of Camera Randomness.

This image began as a gift, then had the brief potential for Great, then receded back down to a lesser gift. The juvenile heron you see here was pausing in a tall pond bank of reeds and flowers just twenty feet from where I and a group of birders were standing. Our binocular and telephoto gazes had been fixed on other birds, farther out in the water, when we suddenly realized this gorgeous creature was practically standing next to us, young enough to be unspooked by a cluster of aging hobbyists. The race was then on to grab some kind of image before he realized that he would be far better off putting some distance between us and him.

The foliage in front of him made autofocus useless, in that my lens would try to render the closest thing to it in sharpest relief, blurring out the bird. Switching to manual, I was racing against the clock to lock in the heron’s face before he could move even an inch and go back out of focus. I got five frames cranked off before he took wing, none of which had been in perfect register. Had I failed? Was I left with a generally bad batch, or could at least one image be said to deliver something more than a perfectly sharp frame might have? I had failed to capture “Greatness”, but had I truly been given a “gift”?

I know what you’re thinking. Photographers are all too eager to excuse their failures and try to see them as strengths, like an indulgent parent who sees a budding Picasso in his child’s incomprehensible crayon scrawl. I’m certainly not immune to my own ego, nor my bias toward whatever wretched messes emerge from my camera.

Still….

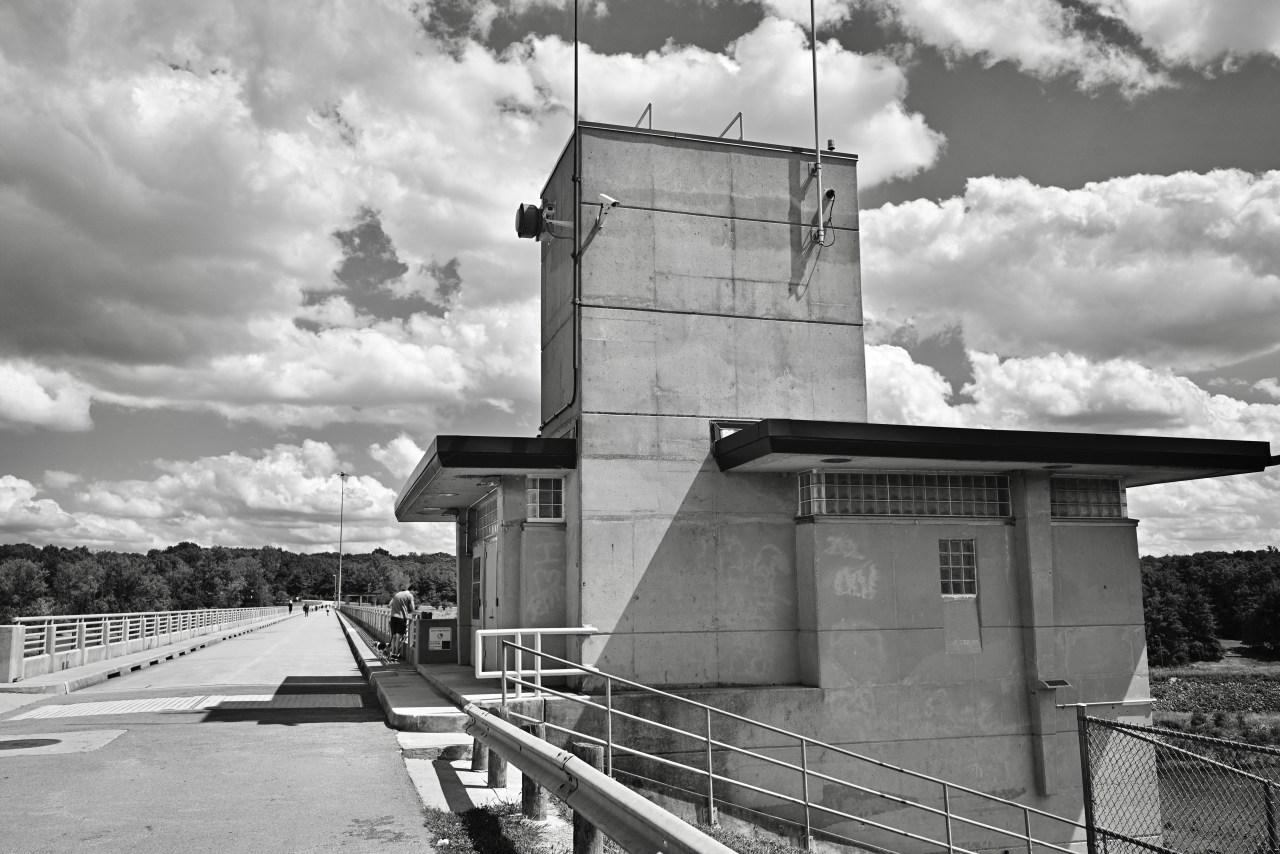

ON MY WAY OUT…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE RECENT DEATH OF MY NINETY-SIX-YEAR-OLD FATHER actually resembled most visits I’ve made to Columbus, Ohio to visit him over the past quarter-century, in that a lot of my alone time was spent trying to reconcile the locales of my youth with the ghosts of things long vanished from those physical places. You can actually go home again, if you can bear the sight of things that you once thought were important, even vital, reverting to be just…..well, things.

No two people, certainly no two photographers, can regard the same scenes and come away with the same experience, and so we make fools of ourselves walking up to vacant lots and remarking to strangers that “there used to be a ball park here”. Not to the strangers’ eyes, certainly, and no longer even to us. Physical sites are imbued with only temporary meaning in one part of our lives, then revert to just their materials and geography once we stop needing them.

Nothing could be more ordinary than this simple arrangement of block concrete, which is adjacent to the spillway of Hoover Reservoir (not the more famous”dam”, nor the more infamous Hoover) on the northern edge of Columbus. Other than its role in providing some recreation and a clean supply of local drinking water, there is nothing visually remarkable about the place to the average photographer’s eye, and yet, to a seventy-three-year old just mourning the passing of a parent, it once held some special magic, and merited one last click.

When I was a boy, decades before farms and fields in the area would be swallowed by freeways and sprawl, motoring from my neighborhood to the Hoover constituted a half-day in the country. Driving our old Plymouth Savoy to the site meant a guaranteed stop at its rudimentary snack wagon (“food truck” for you kids) and a walk out to the spillway, where a thunderous cascade of water would explode forth from one of its release pipes and we kids would terrify our folks by leaning out over the low guard rail that barely separated us from watery doom hundreds of feet below.

I don’t know why I decided, after so many years of passing the reservoir on the way to somewhere else, that I needed one more up-close look. On this trip especially, I seem to have made several mini-pilgrimages to parks and wooded areas that once defined me, very aware that I was walking out of my old life for what now seemed forever. Of course, I will go back to Columbus gain, to see my sister, my adult children, my grandsons, and a dwindling network of old pals. But in some very real way, I was conscious that I walking out of some kind of door for the last time, with once-special places now returning to their normal uses as just more things in the world. A very strange kind of goodbye.

I’LL LET MYSELF OUT

Leave a tender moment alone. —Billy Joel

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE KNOWN MANY CREATIVE TYPES, from writers to painters to musicians to photographers, who struggle with deadlines. Not because they actually can’t complete assignments or projects on time, but because they find it excruciating to pry their fingers off their work, surrender it, and let it stand on its own….to, in effect say, it’s done enough; it’s good enough. Or, more precisely, realizing that it’s as good as I can make it, and that, perhaps, continuing to tinker with it in search of perfection will actually invite more flaws.

We know how to enter the “room” of a piece of work. Knowing when to head for the exit is something else again.

As a photographer who largely works for himself, I usually have the luxury of fiddling endlessly with images in the hope that I can somehow make them one step, one click, one fix closer to “finished”. This is actually a trap. If I were, in fact, delivering work on someone else’s dime, I would know that the delivery date is Friday at 5pm and that’s it. Bam. The rigid forces of the marketplace would guarantee that there would come a point when I would lay down my pencil and hand over the work. When the boss is me, not so much.

600mm, 1/400sec.,ISO 400, f/6.3

Take this image. It was a complete accident, the final image of a series of shots of an egret who had remained pretty much stable near a riverbank as I cranked away. Then, without warning, he decided to fly away, allowing me two panic-driven clicks of his exit within about a second and a half. My autofocus made a brave attempt at freezing the action, but in trying to track the bird, I was bound to create some amount of camera shake, all made worse by the fact that I was clear across the river and zoomed out at 600mm handheld. The second of the two frames largely worked, in that I caught the gorgeous contour of the bird and the reflection of his wings as they lightly skimmed the surface of the water. But the softness bothered me somehow, and so I was stuck with a technically imperfect shot that, for at least an hour or two, I told myself that I could somehow “fix”.

But you can’t really insert precision where it was lacking in the master shot, something I often have to admit only after fruitless tinkering, a desperate chase that leaves me with so-called “improved” versions of the shot that still, somehow, pale next to the original. You have to fight to keep the innocence and discovery in your work. Sometimes that means that you have to show yourself the door before you’re really ready. Often as not, though, it’s the most strategic exit you can make.

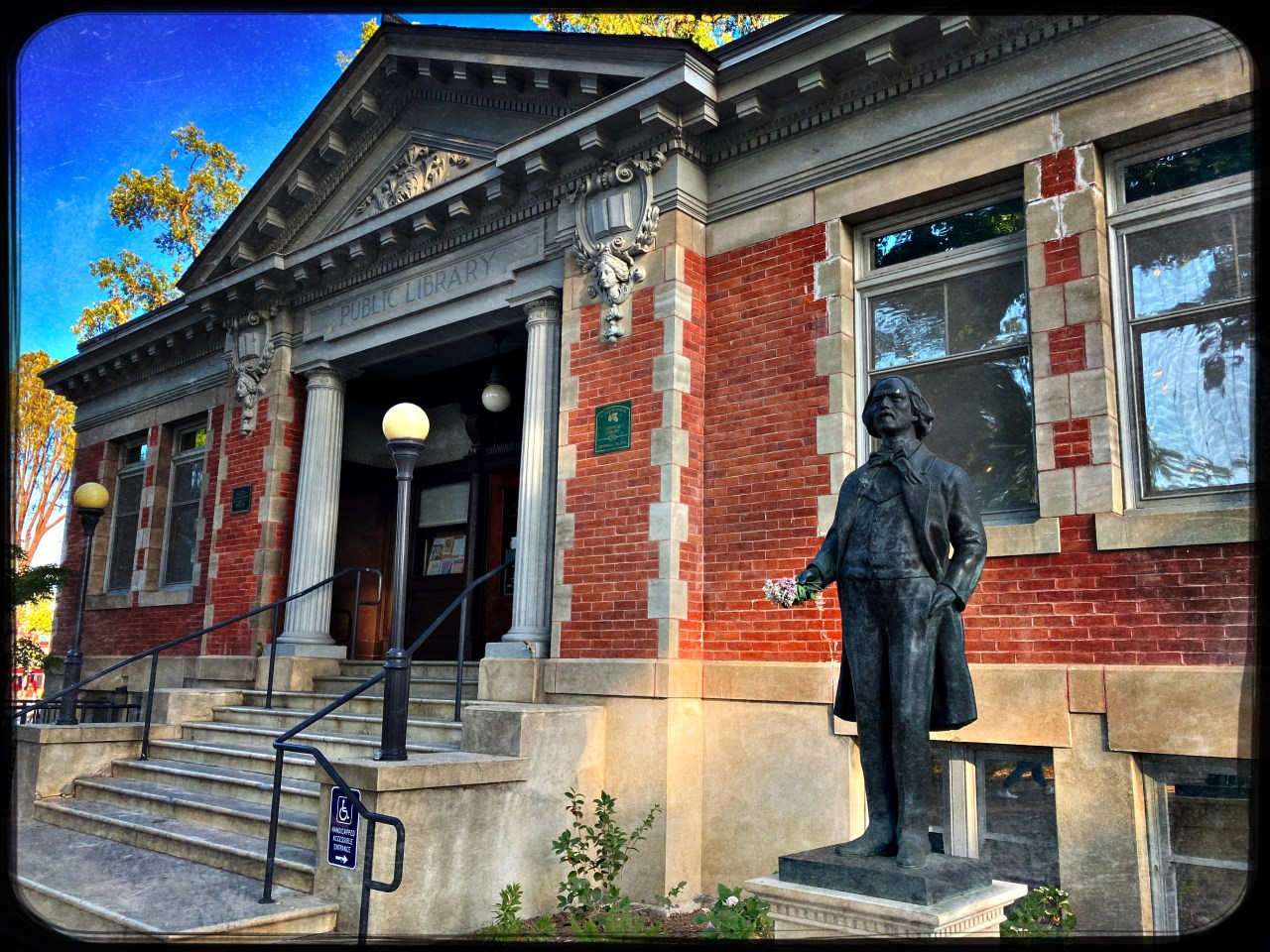

OFF THE SHELF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

JERRY SEINFELD ONCE REMARKED. OF GUYS OBSESSED WITH OVERUSE OF THE REMOTE CLICKER, that they “aren’t interested in what’s on tv; they’re interested in what else is on tv.” Funny and true, and also indicative of some photographers, in that, while we love what our basic gear does, we’re really excited at the prospect of hybridizing equipment from any and all sources. We’re interested in what else our cameras can do.

My 1977 Minolta 50mm, dormant in my closet for over twenty years, now fronting my Nikon mirrorless.

Many of us at least stray slightly from the only-original-manufacturers mindset (that is, only Canon lenses for my Canon camera, etc.), yielding to some degree of lens bi-curiosity, leading us to adapt glass from other makers to find the perfect marriage between body and optic. It’s not always a win for our work, but the journey is far more fun than the destination anyway. And the old hybridizing romance of the DSLR period has easily found a contemporary equivalent with the move to mirrorless cameras, as dozens of third-party equipment houses have rushed modestly-priced adapters to market for converting older glass, including many manual-only lenses, to use on mirrorless platforms. Photographers tend to be tinkerers; they are fascinated by what happens when you do this to this. And now it’s easier than ever to get answers for that tantalizing question.

Like many reading this, I spent my DSLR years adapting old manual primes from the film era, treating myself to optics with all-metal construction, smoother aperture and focus adjustment, superior sharpness, and a huge cost savings. These tended, for the most part, to be Nikkor lenses for my Nikon cameras, and so no adapter was required, since I was going from an F-mount lens to an F-mount body. Then, after making the leap to mirrorless, I adapted the same lenses to continue their use on a Z-body (using so-called “dumb” adapters that don’t communicate with the camera body, another cost-savings for someone who’s shooting without the need for AF). And finally, I’m enjoying going completely off-brand to give new life to optics that have been gathering dust since my first days behind a viewfinder.

Moonstone Beach near Cambria California, 9/6/25, seen through the eye of a 1977 Minolta 50mm prime.

The lens shown here came from a Minolta SRT200, a ’70’s-era SLR that I grabbed for $100 in the ’90’s when my daughter decided to enroll in a high school camera class. The class came and went, but I kept the camera, fitted out with a Rokkor-X MD 50mm f/1.7 prime lens. I spent a lot of time, just before and just after 2000, shooting mostly slide film with it, sticking it in the closet only after the purchase of my first digital point-and-shoot. Learning that, decades later, it could be restored to service as a sharp and clear prime for the mere cost of a $30 adapter put a huge grin on my face, and, at this writing, we have been renewing our old love affair for several weeks. Scores of articles are now online as to the efficacy of this or that bit of “legacy” glass on mirrorless bodies, most written with a flavor of delight, or adventure, or both. Some even claim that such vintage optics perform even better on digital cameras than they ever could on film. Your mileage may vary. As for me, I’m just beginning to explore what else is on my camera.

Oh, and hand me that clicker, willya?

SOOC, and SOwhat

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE THINGS THAT ACCOMPANIED THE FIRST GOLDEN AGE of amateur photography, when most people around the world were just acquiring their very first cameras, was the whole support industry of “how-to” guides, exemplified by Eastman Kodak’s long-running How To Make Good Pictures series of instructional books, along with endless others. These volumes emphasized basic practices for the beginning shooter, from composition to focus, aperture control to basic lighting, and so forth. In the age before complex processing was within reach of the many, such instructionals quickly codified certain steps for “acceptable” images, with a special accent on getting a good result S.O.O.C., or Straight Out Of The Camera. They were technical tips that were adopted by many as aesthetic standards as well.

Zoom forward to the present, where the word “acceptable” is as elastic as the term “normal”, and the “rightness” of the final photographic result is very, very much in the eye of the beholder. We can literally make anything look like anything, and yet this newfound freedom is still a source of controversy for people who define acceptability merely by the standards of recording or documentation. I am surprised, for example, to see on-line critiques of images based on their not being “realistic” or “naturalistic” enough, as if such arbitrary terms even can be applied to an interpretative art form.

Which of the two images shown here, either the SOOC shot (at top) or the one that’s had its texture and tone augmented (just above), is more “real” or “natural”? And in what context? To what purpose? Despite all our years of “how-to” conditioning, isn’t it pointless to reduce photography to a narrow set of acceptable parameters? Moreover, isn’t it obvious that most photographers refuse to be so hemmed in? As photography experiences a renaissance in its third century, the only thing that works in a picture is, to be redundant, whatever works for that picture.

ALL AT SEA

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY RECENT RE-LOCATION TO CALIFORNIA has, in just over a year, already informed my photographic work, especially since I live largely near the Pacific coast. As just one example, my entire attitude toward landscape work has been re-jiggered, mostly due to the fact that I have near daily access to the ocean, which, as either subject or backdrop, seems ever new to me. I was never a “landscape guy” in any committed sense, my passion being concentrated either on street scenes or abstract patterns, which, in architecture, also centered me in cities. Being newly entranced by an area of photography that I always thought of as auxiliary rather than essential, then, requires me to be a lot more deliberate in choosing projects or compositions. It’s easy to get to the beach; it’s harder to get the beach, if you like.

You can see the effort here. What you can’t see is actual planning toward that effort.

One thing I learned pretty fast, and that is that I need to become more of a technician when it comes to even exposures that include say, the brighter surfaces in the sea. It takes a mortifying amount of practice to program either me or my camera (or both) to get balanced shots. The scene shown here is a great example of what I must absolutely not do, and that’s to trust my camera to either full auto modes or a semi-auto setting like Aperture Priority. I simply come away with too many blowouts on the waves, which, as we all know, are unfixable in post. You cannot recover detail that you didn’t capture in the first place. Underexposures can sometimes be mined for additional information, but a whiteout is a whiteout, and, in fact, you can make the entire frame worse by going overboard to fix an unfixable situation.

Shooting this image on full manual and adjusting the histogram for better balance throughout would obviously have prevented some of the damage, but, in a rapidly shifting scene (something that is a constant with “active” landscapes like water) I have ofttimes succumbed to the ease and speed of auto shooting, usually to my regret. And so, as I evolve fully into Beachcomber Boy, I need to re-school myself on all the lessons I have not had to draw upon for most of my recent work. As stupid as it sounds, there is no substitute for actually knowing what you’re doing.

NOTHING IS EVERYTHING IS… NOTHING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS AN OLD VAUDEVILLE JOKE WHERE ONE COMEDIAN ASKS THE OTHER, “so what is it that you do?”, to which the other replies, “nothing.”. “Well, then, says the first, “how do you know when you’re done??” Yes, I know, stupid, but it also explains exactly how I feel when I’m on photographic walkabout.

There is a big difference between having “something” to shoot, i.e., a defined plan or target, and having “whatever”, or, some might say, “nothing” to shoot. The former is for things that you intend, that you want chronicled in a certain manner. Such a shoot may include a few random shots, but the chief objective of the outing is to accomplish a set thing. By contrast, in doing a walkabout, a “wherever my feet lead me” kind of shoot, you are on a much simpler path, in that nothing you do really matters, and the whole experience can be based on pure impulse.

Walkabouts happen frequently for me, since I am notoriously early for every appointment, and many of my family are just as predictably late. And since I am never without some kind of camera, my default action, when I arrive ahead of schedule, is to just start wandering and snapping. At the very least, all those “non-pictures” will teach me a little bit more about whatever kit I’m using, and at the most, I may come home with a surprise or two, such as the image seen here. It’s about as much “of the moment” as it can get, as I was merely walking through a parking garage when its red neon sign appeared overhead through a patterned atrium tunnel. The juxtaposition of the two, mounted against a jet black sky, said take a shot. Not two, or five, or anything that might constitute a deliberate act; a pure distillation of let’s see what happens. And what you see here is all there was; no backstory, no context, no procedure.

Why is this important? Perhaps it’s a reaction against the anti-instinctual habits we acquire over the years, as our gear becomes more complicated and our technique becomes more multi-staged. Perhaps it’s good, once in a while, to reconnect with the kid that originally was so fascinated by the taking of pictures that he/she couldn’t click fast enough, couldn’t wait to get to the next raw sensation. When I can’t find that kid, I panic a bit. His hunger to Plan Later, Just Shoot can still feed something important in me. He makes a big fat itch of himself sometimes, and until I scratch him, I feel a bit lost.

WHAT WILL HAVE BEEN SEEN?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC FRAME, LIKE EVERY OTHER KIND OF FENCE, includes things and excludes things at the same time, creating a double mystery in every image. Why was this information deemed important enough to be “in”? Why were other things forever left outside the perimeter, robbing us of the remaining context of the people or things within? What have we hidden, intentionally or not? What have we deliberately called attention to? What is the tension, the connection between these seen and unseen worlds?

Especially, in older pictures that depict who are no more, their position in the frame and the way in which their own gaze is directed implies things than will forever go unanswered. What, or who, are they looking at? Are they merely lost in reverie, caught accidentally in mid-step, or truly fixated on something or someone about which we can never know? It is the ability of the photograph to both convey and edit information in this perpetually unresolved fashion that contributes to its ongoing fascination. We are being told something; we will never be told everything.

Often, in so-called street work, I find myself seeking out people who, far from actively engaging with the camera, are actually oblivious to it. They are the ultimate candid subjects; those for whom the photographer is completely invisible, and more importantly, irrelevant. This has made me feel a bit of connection to those hobbyists who collect “vernacular photographs”, pictures found in odd lots in junk stores and auctions, made by people they themselves know nothing about. Not only do we find that the eternal verities of humanity are shared pretty much the same way all over the world (a birthday party is a birthday party wherever you go), but the same mystery of in-the-frame/out-of-the-frame unfolds in much the same way for every shooter. Who are these people?, we ask at first, only to realize that, of course, they are all us.

LIGHT BENDERS FROM HECK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE TOUGHEST THINGS TO LEARN IN PHOTOGRAPHY is just how many popularly held beliefs you have to unlearn in order to grow your work. This means trusting fewer “obvious truths” and being open to ideas that seem counterintuitive. One such area has to do with lenses and how they render sharpness.

Many of us learned, early on, that each lens has its own “sweet spot” of focus, and that, on average, it tends to be two f-stops slower (smaller) than the lens’ widest aperture, so that a lens with a maximum aperture of f/2 might have its best, biggest patch of sharpness at about f/5.6. This generally accurate tidbit might easily tempt one to take the idea to its “logical extension”; that is, to assume that, if the aperture is closed down even further, there will be an even greater increase in sharpness. However, as intuitive as that belief is, it’s just not borne out by the raw physics, or by how light actually behaves.

Disclaimer: what follows here is a ridiculously simplified explanation, and I sincerely urge the reader to do much, much more sophisticated research on the subject. It can easily fill up several blackboards and make one feel as if one’s head were stuffed full of cotton, but it’s worth reviewing the full science of it. That said….

If you feel that, since your lens is much sharper and has a better depth of field at f/5.6 than f/2, then you may assume that a really small aperture like, say f/22, will be super-sharp end to end. However, that’s not the way it works. Light rays flow through a large aperture more or less in a straight line, traveling parallel to each other. This favors sharpness. However, once the diaphragm is tightened down further to f/22, the light rays have to crowd together to make it through a very narrow slit, which bends the rays and sends them cascading over top of one another, and that generally leads to poorer focus and loss of detail. Think of your lens’ sweet spot as a Martha Stewart “good thing” and f/22 as Too Much Of A Good Thing. That means that my 50mm’s f/5.6 sweet spot can deliver a shot like the one seen here better than could be had by stopping all the way down.

Of course, it goes without saying that your experience could be different in one particular or another, and I again emphasize that a kid assistant working with Bill Nye the Science Guy could probably have explained the whole phenomenon with greater skill, but the general idea is that lenses perform the function of focus in very different ways depending on what is asked of them. Mastering their potential means mastering your own observations and conclusions, and that means putting in the hours. The best lens in the world can’t eliminate your learning curve. That takes time.

PUT ME IN, COACH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE HEAVIEST LIFT FOR ANY PHOTOGRAPH of a loved one is when time removes the original player depicted in the image, and the picture itself must come off the bench and stand in for that vanished team member, forever after. It’s at a time of personal loss that the casual shots we snap in a careless instant become more valuable than any other commodity. The picnics, the graduations, the weddings, the days at the beach….all are converted in an instant from base metal to gold.

The author and his father, circa 1954.

This week, as my ninety-six-year-old father prepared for his final bow upon the stage, I spent a lot of time, as one does, poring over the photographic tracings of nearly a century of life. Of course, all these candids were only the top layers on my memories, as I still have the ability to place them all in deeper context, to match up the seen with the unseeable. I can’t decide, from minute to minute, whether it’s an exercise in comfort or agony, but I suspect it’s an alloy of the two. I can’t smile without crying and I can’t cry without smiling, and round and round we go.

When we flash a smile, throughout the years, for whoever happens to have just turned up with a camera, we aren’t posing for the ages. We aren’t trying to create an official version of ourselves to stand in for us after we are no longer around. Few of our portraits are formal or official. Beyond that, there is the random ravage of time, which determines which of the thousands of pictures of us will be lost, burned, stolen, or merely vanished, and which ones will survive to mark our passing. There is something horribly fateful in that knowledge. There is always the shot that oh, was taken right after I left the service, or ah, was right before we got married, etc., etc. that may be the one that’s forever vanished beneath the waves. The ones that got away, and all that.

Photographs, for being as recent in our human history as they are, have become our avatars, our “counterfeits”, as Shakespeare used to call cameo portraits. When the real player is tired or fallen, the fates, like some cosmic coach, reaches into the box of photos on the bench and sends in the substitute. It’ll never be enough. But it’s a very powerful little something, and sometime, it hits a grand slam.

RE-FRAMING THE TERMS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN A RECENT POST, I mentioned that my first year in California, has, in photographic terms, been largely reactive. The huge surge in new situations and fresh sensations has truly shaped my images, in that they are predominantly quick snaps fired off during vastly different living scenarios, some kind of attempt to not let anything “get away”. All this rush has cut down the planning time for individual shots. They are, most of them, shot on full auto, or, at the very least, on autofocus modes. But I’ve now settled in, and I need to reassert the instincts and intuitions that made me a photographer in the first place.

It’s time to re-emphasize the basics.

This blog takes its name from The Normal Eye, a book I compiled, nearly twenty years ago, of pictures I made over an entire year’s time with only a manual 50mm prime. The idea was to teach myself patience, composition, instinct and mindfulness by avoiding the trap of bagfuls of specialized gear, and thus hyper-learning how to wring results out of only one optic, a simple, sensitive but unforgiving tool that would force me to plan and direct photos with a finely-tuned intentionality. If I needed a wider shot or tighter shot, I would need to move my feet. If I was uncertain about focus, I’d have to risk being wrong rather than lazily delegate that choice to my camera. It made me work slower, but smarter, and it gave me a template that, years later, I still retreat to when I need to get my brain back into training.

Using automates to be able to shoot on the fly is a luxury, with the gear making all those troublesome creative decisions for me. And the pictures I get, even when my brain is in neutral, are adequate. However, they never aspire to excellence, to risk. For that, I need my mind in full engagement. I need to narrow the choices the equipment provides and make those decisions for myself. This strategy was, years ago, the only path to teaching myself to see, and it is the only sure path I know to refreshing those skills before convenience and impatience make my talents decay. Today, I’m setting out with yet another 50mm prime, shooting on complete manual. I don’t know how long I have to work exclusively with this setup, but I know, from experience, that it will school me anew. And it’s what I need right now.

AND NOW, BACK TO OUR ORIGINAL PROGRAM

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOUR FIRST YEAR IN A NEW PLACE, as far as your photography goes, is a lot like being on vacation, in that a firehose of sensory information is coming on so quickly that, in an effort to not miss anything, you shoot very much on instinct. Everything is new, and therefore fascinating in a way that it won’t be after you’ve logged enough time to regard your new world as your standard environment, instead of just the latest stop on the tour bus. And that changes the way you make pictures.

Snapshots, by their nature, are reactive, and they make perfect sense when you feel like something very fleeting is whipping by you, never to be recovered if you don’t act (snap) immediately. You are not slowing yourself down to make a shot do all that it can do; you’re just making sure you get something in the can, now. And so, in my first year in California, I’ve been shooting like a tourist, as if I soon have to rejoin the rest of the group back at the ruins, so we can move on to the next attraction. I haven’t been approaching scenes or situations with any intent or contemplation. Instead, I’m shooting largely as if I’ll never be here again, or. as if I have to fly home in five days.

I have to rein it in.

I’ve now been to a few locales out here enough times that I am reverting back to my regular program of slowing things down, seeing them from different angles, wondering if I have the right idea for a picture, or, most importantly, whether a thing is even worth a picture in the first place. One such case that I noticed in particular is the Ventura County Fair, which I attended last year in the heat of my first summer along the central coast. The pictures are colorful and bright, but they are merely pictures of masses of people walking by funnel cake and burger stands, and not much more.

This year, in returning to the midway, I stole away from my wife, who had accompanied me for last year’s visit, and started looking for stories, things that might reveal or imply other things. After a ton of walking and waiting, I finally got several images that I felt had been approached with at least a modicum of forethought. Masterpieces? No, but a kind of proof-of-theory revelation. I have to reclaim a more investigative method of framing images. I have to get off the tour bus, and back to real life.