FROM THE VAULTS: TRUTH VS.REALITY (2017)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ASKED IN 1974 BY AN INTERVIEWER ABOUT THE LEGACY OF THE ACTOR JAMES CAGNEY, director Orson Welles replied that while Jimmy “broke every rule”, “there’s not a fake moment” in any of his movies. He further explained that the star of Public Enemy, White Heat and Yankee Doodle Dandy worked counter to all the conventions of what was supposed to be “realism”, and yet created roles which were absolutely authentic. Cagney, in effect, bypassed the real and told the truth.

As do many photographers, it turns out.

We all have inherited a series of technical skills which were evolved in an attempt to capture the real world faithfully inside a box, and we still fail, at times, to realize that what makes in image genuine to the viewer must often be achieved by ignoring what is “real”. Like Cagney, we break the rules, and, if we are lucky, we make the argument that what we’ve presented ought to be considered the truth, even though the viewer must ignore what he knows in order to believe that. Even when we are not trying to create a so-called special effect, that is, a deliberate trick designed to conspicuously wow the audience, we are pulling off little cheats to make it seem that we played absolutely fair.

The first time we experiment with lighting, we dabble in this trickery, since the idea of lighting an object is to make a good-looking picture, rather than to mimic what happens in natural light. If we are crafty about it, the lie we have put forth seems like it ought to be the truth, and we are praised for how “realistic” a shot appears. The eye likes the look we created, whether it bears any resemblance to the real world or not, just as we applaud a young actor made up to look like an old man, even though we “know” he isn’t typically bald, wrinkled, and bent over a cane.

In the image above, you see a simple example of this. The antique Kodak really does have its back to a sunlit window, and the shadows etched along its body really do come from the slatted shutters upon that window. However, the decorative front of the camera, which would be fun to see, is facing away from the light source. That means that, in reality, it would not glow gold as seen in the final image. And, since reality alone will not give us that radiance, a second light source has to be added from the front.

In this case, it’s the most primitive source available: my left hand, which is ever so slightly visible at the lower left edge of the shot. It’s acting as a crude reflector of the sunlight at right, but is also adding some warmer color as the flesh tones of my skin tint the light with a little gold on its way back to the front of the camera. Result: an unrealistic, yet realistic-seeming shot.

There’s a number of names for this kind of technique: fakery, jiggery-pokery, flimflam, manipulation, etc., etc.

And some simply call it photography.

LET THERE BE (MORE) LIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ASK THE AVERAGE PHOTOGRAPHER TO NAME THE GREATEST TECHNICAL ADVANCE of this general era and you will get an incredible range of responses. Given the breadth of technique out there, that’s to be expected. I have my own list of nominees, from lenses to ergonomics to processing platforms, but the one thing that has produced the greatest boost to my work is the superior light gathering power of today’s cameras, a revolution that dates to the first days of digital. That comes down to ISO, and how intuitive and simple it has made every kind of photography.

Consider this image. There is absolutely nothing artistically distinctive about it, but it is nonetheless remarkable, because, just twenty short years ago, it would have been nearly impossible for me to take it in the same way I can take it today. It was captured inside a museum gallery where the only light available was illumination directly next to the exhibits; everything else was swallowed in darkness. It’s hand-held, shot at a 50th of a second, and the lens, a 24mm prime, is fully open at f/2.8. But those things alone cannot deliver a shot like this, unless you factor in the sensor’s light-capturing performance.

Attempting this photo in the analog era, I would have had to purchase the fastest film available, likely with a maximum ceiling of around 800 ASA, and would likely have also had to provide flash or some other illumination to get color registration at this level. A time exposure on a tripod would have helped simplify some of that, but there would have been no getting a sharp shot of the museum guide without a strobe. Overall, a recipe for fuss, gear, expense, and a high degree of unpredictability, especially for an amateur. But that, folks, was film. And speaking of film, cameras that used it could only use one speed per roll. To change to a faster film from shot-to-shot, a separate camera loaded with that specific kind of film would be needed. Not handy.

However, with today’s sensors and processing, shooting this at 5000 ISO is just a matter of dialing it up and doing it. High resolution, low noise, faithful color (since I can also just select the white balance that I want without intricate calculation….another plus)…..it’s all, reliably, just there. I can shoot fast, simply, and with no great mental pre-occupation or guesswork, meaning I can concentrate solely on getting the shot. What other technical innovation over the last generation can possibly compete with that?

Tools and approaches vary by the individual, of course, and no one tech revolution will solve all problems for everyone. But. But. We are quickly approaching the point in photography in which nearly every major obstacle to making exactly the images we want has been overcome. And if that’s not the biggest news ever, then I can’t imagine what is.

HAVE YOURSELF A SNAPPY LITTLE CHRISTMAS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY HOLIDAY SEASON SINCE 2014, THE NORMAL EYE has cast a nostalgic glance backward to the days when the Eastman Kodak Company was the undisputed titan of home photographic supplies and film. The supplies…the cameras, lenses and tools, were mainly sold just once; however, the film was sold and resold endlessly, as the company marketed the concept of capturing life’s most precious moments, convincing us, in fact, that an experience was not quite complete if it were not frozen in time on our billions of Brownies and Instamatics. And nowhere else was Kodak’s perpetual consumption campaign more powerful than at Christmastime.

Over many a yultide, Kodak introduced the point-and-shoot camera, the portable pocket camera, the first practical color print film, and the first affordable systems for producing slides and home movies. The holidays were always high season for get-togethers with loved ones, hence an amazing emotional lever for Kodak. It’s just not a family gathering without pictures, lots of them! And we’ve made it so fast, so convenient, so….normal. No skill our experience needed, encouraged the ads. Just put a Kodak under the tree (tagged with the company’s holiday mantra, “open me first!” and let the snapping commence. Something fun/happy/wonderful may escape into mere memory, so be ready with plenty of film. flash bulbs and batteries.

Kodak Christmas ads were equal opportunity guilt generators, with Mom and Dad sharing the responsibility for a complete chronicle of every happy moment. Pop busy putting together the model train for Junior? Then let Mother step in and catch a few candids of all the joy. Mom showing Sis how her new Tiny Tears doll works? Then it’s Papa to the rescue, immortalizing every instant of happiness.

Years past Kodak’s glory days, today’s photographic habits are now so ingrained that we can no longer separate experiences from the need to document them, often treasuring an image of how happy we were even as the actual details of that happiness fade to gray. But such is the strange contract we all have with photographs. They have been called “a lie that tells the truth”, and sometimes, some strange and wonderful times, that has to be enough. Incredibly, like some sort of Christmas miracle, sometimes it is.

IT’S ALSO ABOUT THE JOURNEY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE TALK A LOT IN THE PAGES OF THIS LITTLE GAZETTE about the difference between process and product, of the things that happen both in our intentions for a photograph and what we hope will be the final rendition. Both steps have their appeal, but I imagine that we spend most of our time thinking primarily about the destination of a picture; the journey to that point, not so much.

For me, birdwatching, which comprises an ever-larger part of my photographic output, is balanced almost perfectly between product and process, between how are we going to find what we’re looking for? and what will be do when we find it? Many birders are also shutterbugs, and so their “product” calculation is, in part, based on the physical mechanics of mastering their gear and settings….which is where I mostly find myself. That means I have to put more work into the “process” part of the equation; that is, not merely taking pictures of birds, but also trying to capture the anticipation and intensity of the people who are seeking them.

I often forget to, in a way, turn the camera around to see the watchers as well as the watched. It really should just half of a balanced approach, but it can actually slip my mind. The entire chronicle of the trip would, of course, include the personalities of the search party as well as whatever quarry we locate. Because, even on days of no birds (of which there are many), you are still spending quality time with quality people on a great walk. And that’s worth a click or two anytime. Product. Process. Both can generate compelling images.

SOME OF’s

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS, BEING MORE OR LESS AS HUMAN as the next guy, are given, at this time of year (December), to compiling “years in review” or “best of” lists, in an effort to encapsulate the previous twelve months and, who knows, make some sense of it all. Such rosters are the go-to crutch of editors around the globe, who lazily assign their worker bees the task of ranking the top rutabaga recipes, the greatest moments in sports, and, inevitably, their own or someone else’s top images.

I find myself at some disadvantage in trying to evaluate my own work, and so I steer away from “best of’s” and stick with “some of’s” instead. I don’t mind compiling galleries that illustrate what I lived through in a year’s time, but I shy away from assigning any absolute value to any of them. I usually take notice, for example, of the tabs that you see at the top of this page, which click to small photo essays on given themes, and I consider refreshing them from time to time, as I have just finished doing with the current choices you see up top. The photographs in these new tabs, Going Coastal, City, Sweet City ’24, and Westward On A Wing, are not intended to stand as my finest work, but merely a chronicle of what larger adventures shaped me between January and December 2024.

Just A Walk At Twilight, Ventura, California, 2024

The biggest change in my life, for example, was deciding to move to California after twenty-five years in Arizona. That has resulted in what I call oceanic immersion, or a glut of images captured near the Pacific Ocean. Going Coastal, then, contains no great artistic breakthroughs; it’s just that the subject matter, especially for a noob, has me, for the time being, under its spell. City, Sweet City ’24 celebrates my return to New York after an absence of over five years, a long stretch in my experience, and Westward On A Wing celebrates my current stage of development as a bird photographer, which also rounds out to about the last five years. Think of the tabs as diary entires, minus the mooning over that cute new girl at school or pressed prom flowers.

As I said at the top, I find myself quite inadequate to the task to determining what my “best” images are. I can really only attest to what has been engaging or fulfilling for me. That’s why it’s a hobby. And, as with all hobbies, I can never really be “done”, which suits me fine. I prefer a life that’s a process instead of a product, a work in progress, a snap away from either success or failure. It’s fun balancing on that edge.

STICK AROUND AFTER THE CREDITS

December 1, 2024, 6:06:50pm, Ventura Harbor Village, California. f/4.5, 1/20 sec., ISO 100

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BACK IN THE DAYS WHEN SOME A-LIST MOVIES WERE PRESENTED as so-called “road shows”, there was an inducement to get people to stay in their seats even after the picture ended. The road show treatment, reserved for such wide-screen wonders as Ben-Hur, How The West Was Won, Lawrence Of Arabia and other epics was created so exhibitors could command premium ticket prices on select films at select prestige theaters, grand palaces where the movies could be stretched into an entire evening’s entertainment. The show included music overtures before the film, the actual dramatic drawing of a theatre curtain, a mid-feature intermission (many of these pictures were quite long), and, after the end title, so-called “exit music”, an orchestral re-statement of the major themes of the score, used to accompany the audience’s departure. The music was so beautiful that it was not uncommon for people to keep their seats until it was finished. Hooray for Hollywood.

6:09:22. f/3.5, 1/80 sec., ISO 100

All of which I’m mindful of when trying to capture a sunset. Of course, we all want the big money shot of the blazing red/orange ball of sun just as it kisses, and then slips below, the horizon. But some of the best and most dramatic displays of light and color happen in the minutes after the ball drops. Some photographers actually prefer the sky’s “exit music” to the sun’s formal “the end”.

And I’m one of them.

The three shots, scene here, of a sunset on the first day of December in Ventura, California illustrates how dramatically, and rapidly, shifts in tone happen within just minutes after a sunset. The earliest frame up top sees the orange from the just-vanished sun radiating more than halfway up in the sky, blending into the last vestiges of a daylight blue. In the second, the red at the horizon has intensified, blending now into a deep purple at it tracks skyward. And finally, all the reds are receding, as a new, deeper blue begins to set the scene for night. All within the space of five minutes.

6:12:38pm, f/2.8, 1/125 sec., ISO 1600. Suddenly, it’s a blue world….

You get the idea. A blazing sun is spectacular at sundown, to be sure; however, the light show that follows, after the movie ends, is so wonderful, you may want keep your seat until the last bit of exit music fades…

FROM THE VAULTS: “Framing Memory”

( All twelve years of THE NORMAL EYE are archived, and you can easily search any month or year by clicking on “Post Timeline” at the very bottom of any page. Here, from December 2018, is a look at the history of the Kodak “Colorama” and its huge role in holiday traditions. )

THE IDEA OF AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHY, the once-revolutionary notion that virtually anyone could own a camera and produce good results with it, came about at the exact point in history as the birth of mass-market advertising. Inventors made it possible for the average man to operate the magic machine, and wily promotion made him want to own one, and, by owning, adopt the habit of documenting his entire life with it. Some companies in the early days of photography excelled in the technical innovations that ushered in the amateur era, while others specialized in engineering desire for the amazing new toy. And no company on earth combined both these skills as effectively as the Eastman Kodak Company.

A super-sized Kodak “Colorama” transparency from the 1950’s.

From the beginning of the 20th century, Kodak’s print ads used key words like “capture”, “keep”, “treasure”, “preserve”, and, most importantly, “remember”, teaching generations that mere memories were somehow insufficient for recalling good times, or somehow less “real” without photographs to document them. The ads didn’t just depict ideal seasonal tableaux: they made sure the scene included someone recording it all with a Kodak. Technically, as is the case with today’s cel phones, the company’s aim was to make it progressively easier to take pictures; unlike today, the long-term goal was to make the lifelong purchasing of film irresistible.

Kodak’s greatest pitch for traveling the world (and clicking off tons of film while doing so) came from 1950 to 1990, with the creation of its massive “Colorama” transparencies, the biggest and most technically advanced enlargements of their time. Imagine a backlit 18 foot high, 60 foot wide color slide mounted along the east balcony of Grand Central Terminal. Talk about “exposure”(sorry).

Sporting the earliest and often best color work by Ansel Adams and other world-class pros, Coloramas were hardly “candids”. They were, in fact, masterfully staged idealizations of the lives of the new, post-war American middle class. The giant images showed groups of friends, young couples and family members trekking through (and photographing) dream destinations from the American West to snow-sculpted ski resorts in Vermont, creating perfectly exposed panoramas of boat rides, county fairs, beach parties, and, without fail, Christmas traditions that were so rich in wholesome warmth that they made Hallmark seem jaded and cynical. It was a kind of emotional propaganda, a suggestion that, if you only took more pictures, you’d have memories like these, too.

More than half a century on, consumers no longer need to be nudged to make them crank out endless snaps of every life event. But when personal photography was still a novelty, they did indeed need to be taught the snapping habit, and advertisers were happy to create one dreamy demonstration after another on how we were to capture, preserve, and remember. The company that put a Brownie in everyone’s hand has largely passed from the world stage, but the concept of that elusive, perfect photo, once coined “the Kodak Moment”, yet persists.

WONDER WHAT THEY MEANT BY THAT…..

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY, BY ITS VERY NATURE, pulls things not only out of their time, imprisoning them in a perpetually frozen state, but also out of their context. Extracted from all the other elements present at the time the shutter snapped, a subject must be judged on its own visual merits. It may, indeed, suggest the other conditions that prevailed when it was in the world; that is, a view of the Empire State implies the unseen remainder of the city skyline in which it exists; however, being captured in a photograph can just as often isolate an object or a person, robbing the eye of what it meant in the flow of regular reality.

Museums operate much like photographs, in that they create exhibits of things that have lost their overall context. We learn what we are looking at through explanatory texts or captions displayed near them, but the complete world the things once inhabited is removed. This forces us, as in a photo, to interpret their visual value to us. Sometimes they become diminished, while in other cases, their force actually increases. In visiting museums, I weigh a lot of factors, from empty spaces to shadow play to composition, but I am predominantly drawn to exhibits because the items in them are no longer merely what they were. My camera can thus contort their reality in a million different ways.

Birds are a prime example. As a birdwatcher, I see living creatures that inhabit an entire ecosystem of activity and place. As a guest in a museum, however, I see them in their corporeal form, perfect, in fact, in every detail, but now just objects to be arranged, lit in a particular way, or even abstracted. They become clay in my fingers, recognizable as birds, certainly, but capable of calling up a host of different associations. I can look at them and imagine majesty, mythical power, menace, or a mixture of all three. It reminds me that pictures are created long before the click, and that no two people can frame up the same subject and get the same result. I know what I mean, but figuring out what you mean, well, that’s the wondrous variance that keeps photography a perpetually unfolding mystery.

AT-BATS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ART IS AN ACT OF FAITH, an affirmation of everything we hope the world to be. To make art is to make good on every gift we’ve ever been given, re-circulating the fresh air of the inner soul through our nostrils and back out into the world through the breath of creation. Art is never merely talent, nor craft; it is far mightier than those things, powerful enough to transform shadows into sunlight, despair into prayer.

Art is the sustaining nutrition of the soul.

Photography, among other arts, has always had the power to transport me somewhere beyond my immediate cares, beyond the arbitrary agendas of any outside authority or regime, indeed beyond time itself. With my eye to the viewfinder, I feel at one with every other act of Creation that has preceded me. I also feel at one with the twelve-year-old version of myself that first picked up a cheap plastic Imperial Mark XII camera (retail cost: $7.00, with flash attachment) and yearned for better results. That yearning has never stopped, nor has the desire to begin afresh from nothing and make something, hopefully something honest.

And so, on this Thanksgiving Day in 2024, I continue to be grateful for every new chance to take my at-bats, to again face the pitcher. Because ideas are limitless; opportunities to capture them are infinite; and because I live in a world where most things, most truly important things are a gift. In the words of the old song….

The moon belongs to everyone

The best things in life are free

The stars belong to everyone

They gleam there for you and for me

The flowers in spring, the robins that sing

The moonbeams that shine

They’re yours, they’re mine

And love can come to everyone

The best things in life are free

PRODUCTION FOR (RE) USE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS TOGGLE BETWEEN TWO APPROACHES TO SUBJECTS, two very distinctive ways of justifying something’s place in a picture. The first, which almost exclusively defined the first age of the young art, was largely about documentation, creating the first visual chronicle of human experience. This surge of reportage resulted in a huge spike in tourism and travel in the 1800’s, immortalized in the billions of post cards and stereo views that “covered” the entire world. We mapped the globe to give everyone their first look at what was going on in the lives of everyone else, with magic lantern presentations and illustrated lectures on the pyramids, the Parthenon, a real, live Indian elephant. We catalogued.

The other approach to subject matter is far more abstract and interpretive. We mechanically capture an object in the same way, but we gentle massage composition, light and lenses to suggest all of the things that it might be, not merely what it is in nature. In this kind of picture-making, we ask the viewer to suspend their instinctual judgement of what they’re looking at and share in the shooter’s idea of all the things that it suggests. In such a situation, to know what a subject actually was designed to be, or do, is actually rather, well, dull, compared to what the mind, freeing itself, will allow it to become. If I were to open up a discussion, for example, on what the true use of the structure shown in the above frame was, just given what’s shown in the image, I’d likely open up a pretty rangy chat, whereas, if I were to photograph the same thing in the context of its intended purpose, it would serve as a document, but not as a point of departure.

Both approaches to material, either the prosaic and the poetic, can make for compelling photographs. As is usually the case, the photog sets the terms of engagement, and decides what kind of conversation he wants to start.

*********

( Note: THE NORMAL EYE is an archive of every article posted on this blog over its first twelve years. To search for posts from any month or year clear back to 2012, just scroll to the very bottom of any page and click on “Post Timeline”. )

ONE-ARMED PHOTOGRAPHY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

COLOR HAS NOW BEEN THE DEFAULT PLATFORM FOR NEARLY EVERY PHOTOGRAPHER FOR SO LONG that many (not all) of us tend to think of monochrome as some kind of deficit, that “real” pictures must, reasonably, be in color. It’s as if, having once put sugar on our corn flakes, we can’t imagine downing a bowl without that sweetness hit, or that trying to tell an effective story in a mono image is like tying one arm behind our backs. MONSTROUSLY HUGE DISCLAIMER: this is NOT the belief of millions of us who still shoot in black and white. I am grading a BIG cultural curve here….

To me, the two mediums are like recipes. One uses a sumptuously wide variety of spices, accents and seasonings to create a rich, full-bodied dish. The other uses a small list of ingredients, but can also result in intense flavor. Neither has a culinary edge or skillbragging rights over the other. In the use of monochrome, it’s all down to approach, which, for me, at the advanced age of 768, means calling on memories from when shooting that way was simply the only feasible choice.

That Wednesday At The Wharf, November 2024

Color was already in rapidly increasing use when I first crawled out of the photographic womb, but the default usage, globally, was still too mono. It was cheaper, for one thing. Also, there were many more people walking around who had trained when there was no other way to go, and their habits informed those of people like me, who were newbies at the time. So, now, when I deliberately conceive a b&w shot, I ask myself what, in that shot, I can achieve without color, or, more precisely, what impact mono will deliver for me that color would needlessly complicate or distract from. I find that if I ask myself, if I were forced to shoot this in mono, how would I make the picture work? Or, more pointedly for fossils of my vintage, how did I use to approach this?

There is nothing more counter-intuitive than a subject like the seaside. There is just so much that scrams at you to “capture it all”, or, in other words, grab every shade and hue of color. But, the fact is, once upon a time, I went to beaches with a basic Kodak and Verichrome film and somehow made at least some pictures that I was happy with. Can I still do that? Photography is a wonderful creative experience because of its blend of scientific surety (if you press this, the camera will do this), and the uncertainty involved in making anything aspiring to art (is this the right approach? Are my instincts correct?). What keeps the whole thing exciting is in trying to get the confidence/anxiety mix just right.

Or understanding that not everything’s black and white.

Unless you want it that way.

TNE VAULT: THE MISSING PIECE

(Note: Every post published on THE NORMAL EYE since its launch in April 2012 is archived. To view any article over the lifetime of the entire TNE series, just scroll to the very bottom of any blog page, click on “Post Timeline”, and select the month and year in which to search. In the meantime, here is a selected “re-broadcast” from 2017 that we hope has enduring value.–MP)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE EASIEST THINGS ABOUT ANALYZING THOSE OF OUR SHOTS THAT FAIL is that there is usually a single, crucial element that was missing in the final effort….one tiny little hobnail, without which the entire image simply couldn’t hold together. In a portrait, it could be a wayward turn of face or hint of a smile; in a landscape it could be one element too many, moving the picture from “charming” to “busy”. The secret to greater success, then, must lie in pre-visualizing a photograph to as great a degree as possible, in knowing in advance how many puzzle pieces must click into place to make the result work.

I recently attended an outdoor dance recital, during which I knew photography would be prohibited. I had just resigned myself to spend the night as a mere spectator, and was settling onto my lawn seat when some pre-show stretching exercises by the dancing company presented me with an opportunity. The available natural light in the sky had been wonderfully golden just minutes before, but, by the time the troupe took the stage and started into their poses and positions, it had grown pretty anemic. And then a stage hand gave me back that missing “puzzle piece”.

Positions, Please, 2014. One light source at dusk, courtesy of an inventive stage tech.

Climbing the gridwork at the right side of the stage, the techie was turning various lights on and off, trying them with gels, arcing them this way or that, devising various ways to illuminate the dancers as their director ran them through their paces. I decided to get off my blanket and hike down to the back edge of the stage, then wait for “my light” to come around in the rotation. Eventually, the stage hand turned on a combination that nearly replicated the golden light that I no longer was getting from the sky. It was single-point light, wrapping around the bodies of some dancers, making a few of them glow brilliantly, and leaving some other swaddled in shadow, reducing them to near-silhouettes.

For a moment, I had everything I needed, more than would be available for the entire rest of the evening. Now the physical elegance of the ballet cast was matched by the temporary drama of the faux-sunset coming from stage left. I moved in as closely as I could and started clicking away. I was shooting at something of an upward slant, so a little sky cropping was needed in the final shots, but, for about thirty seconds, someone else had given me the perfect key light, the missing puzzle piece. If I could find that stage hand, I’d buy her a few rounds. The win really couldn’t have happened without her.

THE INS AND OUTS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FIRST MIRROR WAS A CALM POND, the kind of naturally reflective surface that moved Narcissus to fall in love with his own reflection, much to his later regret. Mirrors of every kind are probably one of the only universal elements in our daily visual experience. Many homes have nearly a dozen in one place or another. In addition to reflecting a reverse view of reality (itself a conflict in terms), they create the illusion of space, bounce and amplify light, and even break the world into panes and shards, partial worlds that both imitate and mock our own.

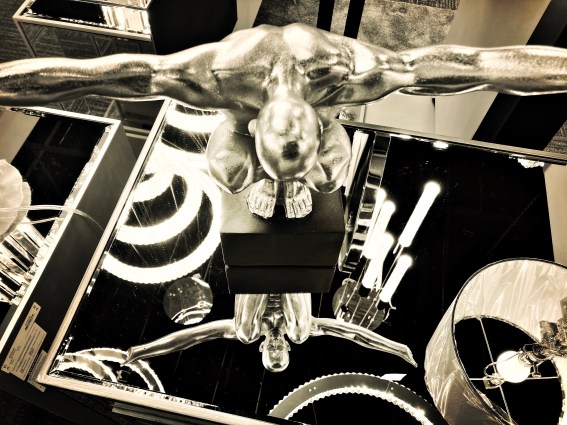

Arc Of A Diver, 2024

Small wonder that photographs are so obsessed with the impact mirrors have on our perception of what’s real, what isn’t, and what falls somewhere in between. When we build so-called “fun houses”, mazes in which to create a slightly panicky, if fun, feeling of being lost, we use mirrors to add to the confusion, to render mysterious the path in or out.

What will get me photographing a mirror (or multiple mirrors) is that very effect of getting lost in some alternate space, the “other” reality that, like Alice, we can step into, often in the hope that the mere reversal of our own world is somehow better, or at least, more interesting. Photographs themselves are lies that tell the truth, that is, they are depictions drawn from reality that, having been extracted from actuality, are immediately rendered as an abstraction of it. Maybe looking into a mirror is as close as most of us will get to entering another dimension, and maybe, just maybe, our fascination with them runs parallel to our wonder at what a camera does, rendering reality and fantasy equal, if only for an instant.

INVISIBLE MIRACLES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN YOU’RE A CITY THAT HOSTS OVER EIGHT MILLION PEOPLE, certain things, even certain extraordinary things, are bound to get lost in the shuffle. In fact, maybe “shuffle” is the perfect word for what happens to people in a town like New York; they become part of an endless mixing of cards, from Joker to Knave, King to commoner, in an equally endless jumble of encounters. Maybe the lyric “if I can make it there” is more correctly worded “if I can get noticed there”. The sheer speed of the shuffle guarantees that the daily menu of things contains many unseen tragedies, many invisible miracles.

The city is so very crammed with every aspect of the human experiment that it is, by definition, jam-packed with extraordinary talents, great feats. There is, on any given day, an embarrassment of artistic riches that just passes unseen. In other places, the marvelous is more of a rarity. In New York, it’s the very mortar between the bricks. Where else but in New York could a vast greenspace like Central Park be merely part of the local scene, as if it were an old lady’s backyard garden? And where else but in Central Park could a superb saxophonist, like the one seen here, merely be the latest amazing musician you encountered on your morning stroll, halfway between the a capella quartet near the children’s zoo and the gypsy accordionist next to the Bethesda fountain?

The most New York thing about this player’s performance, however, is the degree to which he is being regarded not as an extraordinary musician, but as just another element in the daily mix of sensations. As a frequent visitor that is not a native, my first instinct is still to point a camera at this gentleman, because of course he must be acknowledged, and of course people should struggle to be aware of him. But in Manhattan, there is always the next sensation, the next show, just as, if you miss the latest 7 train, there will be another one just as good arriving in the next few minutes.

Maybe if I were ever to become an actual NYC resident, I would eventually get to the point where more of the city’s on-tap miracles would become invisible to me, so commonplace as not to even merit a camera click. But a regular willingness to be surprised, even amazed, is at the heart of every photographer I have every admired, and, so far, it’s an instinct that has served me well. Maybe I’m just not very sophisticated, living up to the Ohio farmboy rep many have hung on me, the little frog awash in the big pond, and so on.

Maybe I am, indeed, every inch a hayseed. A cornball. A bug-eyed kid agog on his first visit to the circus.

Cool.

I can live with that.

A PLAGUE ON ALL THEIR HOUSES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHARAOH WAS A TOUGH SELL.

The infamous Egyptian needed a lot, and I mean a lot of convincing that things needed to change. A guy named Moses pitched him the idea of a new world order, a fresh model of the world in which one man simply didn’t enslave his brother. Simple. Still, Mo had to take several meetings with the sovereign to get the concept across.

Took some boils. Some frogs. Some locusts. And a few other subtle little warning signs that Pharoah’s worldview wasn’t… sustainable.

Then came the ultimate plague. Imminent destruction, after which the terrified tyrant finally, finally agreed to let Moses’ people go. And still he tried to change his mind. Humans seem, always, always, always, to choose negative feedback as their only means of improvement. We don’t even believe there even is crap until said crap hits the fan. Which brings us to this week, when I found myself looking across the street at this:

In California, the Santa Ana wind season is as predictable as spring rain. One day, you’re a cheeseburger in Paradise. Next day, you’re on Mother Nature’s s@*tlist. The cloud seen here appeared out our front window in Ventura as a result of the S.A.’s whipping through Camarillo, a town just twenty miles away. Within minutes of an ignition incident that, at this writing, still remains a mystery, the seasonal gusts transplanted flaming embers onto the rooves of dozens of mini-mansions, landing as well on vast swaths of crackling-dry brush and forests, spreading over 20,000 acres in less than a day, charring over 120 homes to ash and placing all surrounding towns on air-quality lockdown.

The usual platitudes about climate change were trotted out as vast teams of responders raced to outpace the blaze, which is, as I write this, is inching nearer containment. I certainly wasn’t the first to take a snap of Nature in the act of bucking us off her back, of returning the favor for our attempted murder of the planet by deciding to murder back a little. Hell, I’m sure that, had he an iPhone handy, Ramses himself might even have reacted to the horror unfolding before him by snapping a selfie of he and the wife posed before a sea of locusts. As photographers, we need to be constantly bearing witness to what’s already happening. And we have to stop thinking of climate change as something “out there, over there”. As the Monkees sang so long ago, “so you better get ready; we may be coming to your town..”

WHENEVER WHATEVER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT IS ASSUMED THAT ART IS MEANT TO EXPLAIN THINGS, to illuminate the dimmer corners of our perception. Or at least that’s what the logical side of our brain wants to believe.

In fact, art is not a settler of disputes, but rather a disrupter. It starts more arguments than it decides, and, properly done, poses more questions that it can ever answer. Art is meant to upset the applecart.

Nearly every enduring piece of art, that is, work that has had a sustained impact over time, enters the world as a despised outlier. The first words that great much of great art are not “what genius!” but more like “what is that supposed to be?” And so it goes with photographs, the ones we view that others have created and especially the ones we create ourselves. We have, of course, certain intentions for pictures as we plan them, but, in many cases, some other spirit gets into our head, in the nanosecond-long decision to shoot or not shoot, and it can leave us with pictures we might even like, but certainly do not understand.

I don’t know where this came from.

It’s not a particularly attractive subject, and as chronicle, narration or commentary, it doesn’t really justify its existence. And yet it got here, and, I have admit, I rather like it. I just have nothing to say about it.

Sometimes an image just is, and despite all the overwrought captions that might accompany it, from critics, museum curators, or we ourselves, it may never be anything else but what it is. It doesn’t fit a ready-made category; it doesn’t change the world. It just represents a frozen abstracted moment snatched from billions of such moments, all those other times in which we might have snapped the shutter but, for some reason or another, didn’t. Photographs are a random sampling of time, and sometimes the sample presents nothing other than a cipher. And I suppose that’s okay. And even if it’s not, it’s art, so in most cases, all we can do is ask, “what’s that supposed to be?”

R&G in NYC

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LIFE, IN GENERAL, HAPPENS QUICKLY, a condition that photographers, out of necessity, learn to live with. We decide in mere instants what gets stored into our little boxes, evaluating the “lose/keep” equation with whatever scant time we’re given. Some places, admittedly, afford us decent stretches of contemplation, allowing us to sculpt and shape an image at our leisure. You know; the “park my tripod and wait hours for the ducks” type of picture.

And then there’s shooting in New York.

Shooting on semi-automatic mode, perfect for nailing the basics when speeding through busy Manhattan.

Manhattan may not be the place were impatience was born, but it certainly is the town where it is most practiced. On my recent “reunion” with the city (after five years away), I found myself longing for the occasional moments of recent visits, when I could at least have the luxury of five to ten seconds to size up and calculate a shot. In such cases, as is my usual preference, I would shoot on full manual, delighting in being able to be discriminating, even choosy, in my execution. But this time around, I found myself in the company of several other people wherever I went. Thus, their “mission”, whether it was to catch the 7 train or a Broadway curtain, became my mission, meaning I had to be in nearly constant motion. As a result, manual shots were simply going to take too long, with an endless chorus of “wait just a sec!” from me, answered by annoying looks from the other folks in the crowd.

And thus, for the first time in what seemed forever, I went into R&G, or what time constrained fashion photographers call “run and gun” mode. I pre-selected an automatically determined aperture (typically f/5.6 or f/8), with as much customizing for color and contrast as was called for in most urban situations, and locked it in on one of my Nikon’s “U” mode switches, effectively converting the camera into a point-and-shoot. Don’t get me wrong; semi-automatic modes are great. It’s just that I myself hate to overly rely on them, and even in a situation where I have to use them, I wander back into manual as often as time will permit. However, let’s face it, when you’re bringing up the rear on a crowd of people who are hell bent on getting somewhere fast, you either make the deal and make your life easier, or else make everyone’s life harder.

Whoops. What’s this ring marked “focus” for?

The risk of doing this all came back to haunt me later, when I was back in Los Angeles working a subject where I could take my time, and thus was using a fully manual lens. The first time I got into a minor time crunch, I continued to assume, deep in my lizard brain, that the camera would nail the focus for me, when, in fact, I was neglecting my job of doing it myself, resulting in a passel of gooey, fuzzy shots, all wonderfully composed and exposed, all as soft as a 1910 postcard (see above). The moral here is to be mindful at all times, which for me, usually means taking complete responsibility for a shot. Quite simply, convenience makes me lazy, and laziness makes me careless. Like native New Yorkers who’ve just risen to meet the stimulus level of their very busy city, I accept it as the price of doing business.

UNTIL THE NEXT THING COMES ALONG

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM NO STATISTICIAN, but it’s a safe bet that staring at one’s phone may be one of the most universal of human behaviors in this, the year of Oh Lord, 2024. However, as a photographer, and one who seeks the street over every other available canvas, I would bet that the number one human pastime, by a mile, is waiting.

In trying to catch homo sapiens in his most native (candid) state, I find cell phones to be a forbidding barrier between me and the human face. Expressions of any revealing sort seem to simply drain out of our features when we are transfixed on screens, and the heart and soul of street photography is showing people in the act of reacting; thinking, enjoying, interacting, celebrating, dreading, wishing, raging, whatever. And the unavoidable pauses imposed on us while we are waiting are rich with all of that, in a way that “man on a phone” just ain’t.

And there is still so much of this loot to mine; we wait on trains, buses, Ubers, fate, fortune, accident, each other. We must stand in line and on corners and tap our toes impatiently until the light changes, until the moment arrives, until something delivers a shift in the life equation. And in those dead spaces, we spell out spectacular ballets, not only with our faces, but with our bodies, and how they move in relation to other bodies, other fates. And, like the colorful glass shards within a kaleidoscope, every fresh shake of destiny calls up patterns we somehow never saw before.

The activity of making photographs can be like Lucy and Ethel sorting chocolates on a high-speed conveyor belt; there is only a brief instant in which to decide what goes where, whether any of it is worth saving, or whether we should just pop it down our shirt. The shirt shots are forgotten quickly. The stuff that gets sorted correctly teaches us things about ourselves.

AND IT WAS ALL YELLOW….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE LATE COLUMNIST PETE HAMILL ONCE DEFINED A “REAL” NEW YORKER as one who could tell you, in great detail, what a great town New York used to be. I was born in Ohio, but, as I married a woman who grew up in the city and its immediate environs, I have been privileged to visit there scads of times over the past twenty years, enough that I have been able to compile my own personal list of longings for Things That Have Gone Away in the Apple. There are the usual pangs for beloved bars and restaurants; bittersweet memories of buildings that fell to the unfeeling juggernaut of Progress; and the more abstract list of things that could be called How We Used To Do Things Around Here.

For me, one of those vanishing signposts of all things Noo Yawk is the great American taxi.

Take Me Uptown, October 12, 2024

As the gig economy has more or less neutered the cab industry in most cities, the ubiquitous river of yellow Checkers that used to flood every major NYC street at all turns is now a trickle, as Uber and Lyft drivers work in their own personal vehicles, causing one of the major visual signatures of life in the city to ebb, like a gradually disintegrating phantom. As much as the subway or sidewalk hot dog wagons, cabs are a cue to the eye, perhaps even the heart, that a distinct thing called “New York” endures. As a photographer, I’ve caught many huge flocks of them careening down the avenue over the years, even on days when I couldn’t, for the life of me, get even one to stop for me. Now, on a recent trip that was my first time in New York in nearly five years, spotting even one Checker was something of an event for me, and suddenly posed a bit of a photographic challenge.

The problem with taxis, now, is to show not only the physical object itself, but to visually suggest that it is slowly going ghost, fading into extinction. In such situations, I find myself with the always-tricky test of trying to photograph a feeling, finding that mere reality is, somehow, inadequate to the task. It bears stating that I am, typically, a straight-out-of-the-camera guy; I make my best effort to say everything I have to say before I click the shutter. That’s neither right nor wrong; it’s just the way I roll. And so, for me to lean heavily on post-tweak processing, I have to really be after something specific that I believe is outside of the power of the camera itself. The above shot, leaning heavily on such dream-feel, is even more ironic, because the Checker in question is no longer a working unit, but a prop parked permanently in front of a funky-chic boutique hotel. In other words, a museum piece. A relic.

Like moi.

Pete Hamill knew that New York’s only perpetual export is change. Managing that change means managing ourselves; knowing what to say hello and goodbye to; and hoping that we guess right most of the time on what’s worth keeping. Or maybe, just to forever hear a New York cabbie shouting over his shoulder to us, “Where To, Mac?”

REDEMPTION, ARRIVING ON TRACK 11

In the old time, you arrived at Pennsylvania Station at the train platform. You went up the stairs to heaven. Make that Manhattan. And we shall have it again. Praise All.

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan

Main concourse, Moynihan Train Hall, New York City

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR THOSE WHO LIVE OUTSIDE NEW YORK CITY, it is hard to express the sense of loss that’s is still felt locally over the 1963 demolition of the old Penn Station railroad terminal. Crumbling from age and neglect, it was one of hundreds of landmarks that fell to the wrecking ball in an age where so-called “urban renewal” reigned supreme, and its end has continued to haunt urban planners ever since, as the very definition of a wasted opportunity. Today, classic buildings are more typically salvaged and repurposed, allowing their storied legacies to write new chapters for succeeding generations. Penn Station’s death was the Original Sin of a more careless age.

But sins can sometimes be redeemed.

“The Hive” , a dramatic art installation inside the 21st Street entrance to Moynihan Train Hall.

Around 2000, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who, years before, had worked as a shoeshine boy inside the first Penn Station (which was “replaced” by a grim dungeon in the ’60’s on its original site), began to float the idea of augmenting rail access to Amtrak and other carriers by recreating the majesty of the old building in the most obvious place; across the street. Turns out that the terminal had a near-twin, just beyond the crosswalk on Eighth Avenue in New York’s old main post office, which, like the train station, was designed by the legendary firm of McKim, Mead & White. By the start of the 21st century, the post office, by then known as the James Farley building, had already begun to move many of its operations to other facilities, heading for white elephant status in one of the city’s most expensive neighborhoods. By the senator’s death in 2003, funding for what many locals were already calling the Moynihan Train Hall went through years of fiscal stop-and-start, careening like a foster child through the hands of half a dozen different potential sponsors. Construction finally began in 2017, with special care taken to preserve and restore the post office’s massive colonnade entrance, which was, itself, protected with landmark status.

On January 1, 2021, almost as a symbol of New York’s resurrection following its year-long struggle as the first epicenter of the Covid pandemic, the completed Moynihan Train Hall was finally dedicated by New York governor Andrew Cuomo. My photographs of the site now join those of millions of others as testimony to the power of the human imagination, as do the Hall’s waiting-room murals, which illustrate the grandeur of the terminal’s long-vanished predecessor, poignant reminders of the new building’s purpose in redeeming the sin of letting the old one be lost. Among the mural captions are the words of Daniel Patrick Moynihan himself, celebrating the town’s unique trove of tradition and talent:

Where else but in New York could you tear down a beautiful beaux-arts building and find another one across the street?

Amen. Praise all.