BASIC CABLE

In many ways, the Brooklyn Bridge, although not a “land” edifice, is the first of New York’s skyscrapers, and an elegant reminder of a bygone era. Three-shot HDR blend, shutter speeds of 1/160, 1/200, and 1/250 sec., all F/11, ISO 100, 55mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE ANY NUMBER OF LANDMARKS IN THE GREATER NEW YORK AREA which reward repeated viewings. Their mythic impact is such that it is never dulled or diminished. On the contrary, these special places (in a city which boasts so many) actually reveal distinctly different things to different visitors, and, doing so, cannot be exhausted by the millions of interpretations of them that flood the photographic world.

We make pictures of these objects, pictures of the pictures, a tribute picture to someone else’s picture, an impression of someone’s painting. We shoot them at night, in close-up, in fisheye, in smeary Warholian explosions of color, in lonely swaths of shadow.

For me, the Brooklyn Bridge is about two things: texture and materials.

After more than a century over the East River, John and Washington Roebling’s pioneering span, the first steel cable suspension bridge in the world, shows its wear and tear as a proud trophy of its constant service. The delicate and yet sinewy cables, amazingly strong interwoven strands of what Roebling manufactured under the name “steel rope”, are the most amazing design elements in the bridge, presenting an infinite number of kaleidoscopic web patterns depending on when and where you look.

As simply stunning as its two towers are, it is its grid of steel that mutates, shimmers, and hypnotizes the visitor as he makes his way past the crushing mobs of walkers, runners, skaters and cyclists that clog the span’s upper promenade from dawn to dusk. To show the bridge and only the bridge is a challenging trick. To get the dance of angles and rays that the cables have to offer in a way that speaks to you is both frustrating and fun.

Browse through several hundred amateur views of the bridge in one sitting sometime: marvel at how many ways it stamps itself onto the human imagination. Here, I tried to show the steady arc of the master cables as they dip down from the eastern tower, lope into a dramatic dip, then mount to the sky again to pass through the anchors on the western tower. HDR seemed like the way to go on exposure, with three separate shots at f/11, blended to maximize the detail of this most decorated of urban giants.

Next time, some other picture will call out to me, and to you. The bridge will display all the ways it wants to be seen, like a magician fanning out a trick deck. Pick a card, it invites, any card.

Doesn’t matter which one you choose.

They’re all aces.

Thoughts?

Related articles

- Video: Building the Brooklyn Bridge (history.com)

- Brooklyn Bridge Manhattan (markd.typepad.com)

MAKE SOMETHING UP

Table-top romance gone wrong. Plastic Frank runs out on his clingy and equally plastic girlfriend. Shot on a tripod in darkness and light-painted with hand-held LED. 15 sec., 5/4.5, 30mm and, most importantly, since it’s a time exposure, stay at ISO 100. You’ll have plenty of light and keep the noise to a minimum.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS ONE PARTICULAR AREA WHERE, ALL AESTHETIC DEBATES ASIDE, DIGITAL BEATS FILM COLD. That, of course, is in the area of instantaneous feedback, the flexibility afforded to the shooter of adjusting his approach to a project “on the fly”. Simply stated, the shoot-check-adjust-shoot again workflow permitted by digital simply has to prevent more blown shoots and wasted opportunities than film. Shooting a tricky or rapidly changing subject with film can be honed to a pretty sure science, to be sure, especially given years of practice and a keenly trained eye on the part of the person behind the lens. However, a sizable gap of luck, or well-placed guesses remains, a gap narrowed by digital’s ability to speedily provide creative feedback. Release the hounds on me if this makes me a heretic, but as a lover of film, I still prefer the choices digital presents. I don’t have to hate horses to love automobiles.

The digital edge comes through to me especially in table-top shoots executed in darkness and illuminated with selectively “painted” light. I have already written on the general technique I use for these very strange projects in a post called Hello Darkness My Old Friend, so I won’t elaborate on that part again. What I will re-emphasize is that these kind of shots can only be arrived at through a lot of negative feedback, since hand-applied light sources produce drastically different results with every “pass” of the LED, or whatever your source of illumination may be. It’s also hard to find a shot that you love so much that you stop tweaking the process. The next shot just may afford you the quick flick of the wrist that will dramatically shift or redistribute shadows or re-jigger the highlighting of a surface feature.

Tends to fill up those rainy afternoons in a jiffy.

For the above image, I rescued two old dolls from the ash can for one more chance at fame. A friend who knew I was a lifelong Sinatra fan gifted me years ago with a beautifully detailed figure of Ol’ Blue Eyes in his trademark fedora and trench coat, the perfect get-up for hanging out underneath lonely, dim streetlights after all the bars have closed. The other figure is of course a Barbie, left behind when my stepdaughter headed off for college. Normally, these two characters wouldn’t exist in the same universe, and that was what struck me as fun to fool around with. I started to see Barbs as just one of a series of romantic conquests by The Voice on his way through the Universe of Total Coolness, with the inevitable bust-up happening on a dark street in the wee small hours of the morning.

For this shot, the idea was to light just enough of Frankie from above to suggest the aforementioned street lamp, accentuating the textures in his costume and the major angles of his face, without making his head glow so much as to underscore the fact that, duh, it’s made of plastic. The old Barbie had major hairdo issues, but hey, that’s why God made shallow focus. What I got wasn’t perfect, but then, it never is. The important thing with these projects is to make something up and make something come alive, to some degree.

Sadly, Barbie was probably the best thing that ever happened to the Chairman, something he’ll no doubt realize further down that long, lonesome road, looking for answers at the bottle of a shot glass. Hey, his loss.

So goodbye, babe and Amen / Here’s hoping we’ll meet now and then / It was great fun / But it was just one of those things…..

Related articles

- Swank or Rank? Frank Sinatra’s Former Penthouse Hits the Market for $7.7 M. (observer.com)

- tips for fun “everyday” photos. (eliseblaha.typepad.com)

- Hello Darkness My Old Friend (thenormaleye.com)

9/11: ANOTHER KIND OF ANNIVERSARY

One of the two pools marking the foundations of the original Twin Towers. This began as a single exposure, then was augmented by copying the shot, adjusting the copy, and blending the two into a kind of synthetic HDR image in Photomatix.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THIS WEEK, THE SPACE AT GROUND ZERO marks an anniversary that is slightly different from the annual reverences afforded the fallen of September 11, 2001. Even as we put a little more chronological, if not emotional, distance between ourselves and the unspeakable and obscene events that tore the fabric of history on that morning, we begin a second era of sorts, as we mark the first year of operation for the 9/11 Memorial that tries so nobly to advance, if not complete, the healing process. The site, specifically the pools marking the foundational footprints of the north and south towers of the World Trade Center, is no less noble because it has been asked to provide an impossible service. Some things are beyond our reach, but that does not mean that the reaching effort should not be made. Something must endure that physically, visually states who our lost brothers and sisters were. And even a compromised version of that effort, wrested from people’s individual hearts and needs in an agonizing discussion, needs to be attempted.

Visiting the site just two months after its opening last year, I asked myself, how could we have done better, or more? Is there enough, just enough here, to fight off our lazy national habit of collective amnesia? Is there at least a start, marked on this spot, at trying to makes these names matter and persist in memory?

Every day, thousands ask that same question, and there are endless versions of the answer. It’s a gravesite, but a gravesite that is missing many of those being remembered. It is a memorial, but unlike most memorials, it is not located on a neutrally designated “elsewhere”, but on the actual place where the victims fell. It is a beautiful thing that evokes horror, and it is a place of horror where beauty is sorely needed to make going forward imaginable. Standing at the pool’s perimeters, you are struck silent, and you worry over the day when silence may not be the first response to this vista, as, properly, it still is at Gettysburg and Pearl Harbor. And we wish we could know that there was even one atom of comfort afforded by this effort to those left behind, many of whom were annihilated no less in spirit than their loved ones were in fact. If you ever pray here, that’s what you pray for.

Shooting the above image, I wanted to wait for the morning surge of visitors to clear away as completely as possible. I felt, and still feel, that the site itself is at last, a noble thing, and neither I nor any other people around it can help breaking the visual serenity it presents. My shot is also, now, a bit of a time machine, since the rebuilding of the WTC site is now nearer completion by a year. The weather that morning was flawless, in a way in which, on every other place on the earth, does not automatically trigger a feeling of foreboding. I wished I was a better photographer, or that, on that morning, I could become one, if even for an instant. Looking around, I saw many others making the same vain wish. And, in the end, I still feel that I left something untold. But, whatever I captured was at least my personal way of seeing it, and it was about as close to “right” as I was going to get.

And getting “as close we can” is what we have to settle for, at this point in time, in processing the events of 9/11. I am always struck, in reading the remembrances from surviving families and spouses, by how absent of hate and anger most of them are. They fight only to understand, to place it all in some kind of workable context for living. Many of us may never get there. However, life is a journey, and, today, as with all of the anniversaries of this tragedy, we have to hope that we can at least stay on the path toward discovery and peace. The memorial is the first step in that journey.

Related articles:

- NYC 9/11 memorial surpasses 4 million visitors (kfwbam.com)

A BLOCK OF THE MILE

The building that originally housed Desmond’s department store, and one of the mostly intact survivors of a golden age of Art Deco along Los Angeles’ historic “Miracle Mile”.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CALIFORNIA’S CITIES, FOR STUDENTS OF DESIGN, contain the country’s largest trove of Art Deco, the strange mixture of product packaging, graphics, and architectural ornamentation that left its mark on most urban centers in America between 1927 and the beginning of World War II. The Golden State seems to have a higher concentration of the swirls, chevrons, zigzags and streamlined curves than many of the country’s “fly over” areas, and the urban core of Los Angeles is something like a garden of delights for Deco-dent fans, with stylistic flourishes preserved in both complete buildings and fragmented trim accents on business centers that have been re-purposed, blighted, re-discovered, resurrected or just plain neglected as the 20th century became the 21st. And within that city’s core (stay with me) the up-again-down-again district once dubbed the “Miracle Mile”, centered along Wilshire Boulevard, remains a bounteous feast of Deco splendor (or squalor, depending on your viewpoint).

CALIFORNIA’S CITIES, FOR STUDENTS OF DESIGN, contain the country’s largest trove of Art Deco, the strange mixture of product packaging, graphics, and architectural ornamentation that left its mark on most urban centers in America between 1927 and the beginning of World War II. The Golden State seems to have a higher concentration of the swirls, chevrons, zigzags and streamlined curves than many of the country’s “fly over” areas, and the urban core of Los Angeles is something like a garden of delights for Deco-dent fans, with stylistic flourishes preserved in both complete buildings and fragmented trim accents on business centers that have been re-purposed, blighted, re-discovered, resurrected or just plain neglected as the 20th century became the 21st. And within that city’s core (stay with me) the up-again-down-again district once dubbed the “Miracle Mile”, centered along Wilshire Boulevard, remains a bounteous feast of Deco splendor (or squalor, depending on your viewpoint).

The Miracle Mile was born out of the visionary schemes of developer A. W. Ross, who, in the 1920’s, dreamed of drawing retail dollars to an area covered in farm fields and connected only tentatively to downtown L.A. by the old “red car” trolley line and the first privately owned automobiles. Ignoring dire warnings that the creation of a massive new business district in what was considered the boondocks was financial suicide, Ross pressed ahead, and, in fact, became one of the first major developers in the area to design his project for the needs of passing car traffic. Building features, display windows, lines of sight and signage were all crafted to appeal to an auto going down the streets at about thirty miles per hour. As a matter of pure coincidence, the Mile’s businesses, banks, restaurants and attractions were also all being built just as the Art Deco movement was in its ascendancy, resulting in a dense concentration of that style in the space of just a few square miles.

The period-perfect marquee for the legendary El Rey Theatre, formerly a movie house and now a live-performance venue.

It was my interest in vintage theatres from the period that made the historic El Rey movie house, near the corner of Wilshire and Dunsmuir Avenue, my first major discovery in the area. With its curlicue neon marquee, colorful vestibule flooring and chromed ticket booth, the El Rey is a fairly intact survivor of the era, having made the transition from movie house to live-performance venue. And, as with most buildings in the neighborhood, photographs of it can be made which smooth over the wrinkles and crinkles of age to present an idealized view of the Mile as it was.

But that’s only the beginning.

On the same block, directly across the street, is another nearly complete reminder of the Mile’s majesty, where, at 5514 Wilshire, the stylish Desmond’s department store rose in 1929 as a central tower flanked by two rounded wings, each featuring enormous showcase windows. With its molded concrete columns (which resemble abstract drawn draperies), its elaborate street-entrance friezes and grilles, and the waves and zigzags that cap its upper features, the Desmond had endured the Mile’s post 1950’s decline and worse, surviving to the present day as host to a Fed Ex store and a few scattered leases. At this writing, a new owner has announced plans to re-create the complex’s glory as a luxury apartment building.

The details found in various other images in this post are also from the same one-block radius of the Wilshire portion of the Mile. Some of them frame retail stores that bear little connection to their original purpose. All serve as survivor scars of an urban district that is on the bounce in recent years, as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (installed in a former bank building), the La Brea Tar Pits, and other attractions along the Mile, now dubbed “Museum Row”, have brought in a new age of enhanced land value, higher rents and business restarts to the area. Everything old is new again.

The Wilshire Boulevard entrance to Desmond’s, with its period friezes, ornate grillwork and curved showcases intact.

Ironically, the district that A.W. Ross designed for viewing from behind the wheel of a car now rewards the eye of the urban walker, as the neighborhoods of the Miracle Mile come alive with commerce and are brought back to life as a true pedestrian landscape. Walk a block or two of the Mile if you get a chance. The ghosts are leaving, and in their place you can hear a beating heart.

Suggested reading: DECO LAndmarks: Art Deco Gems of Los Angeles, by Arnold Schwartzman, Chronicle Books, 2005.

Suggested video link: Desmond’s Department Store http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJj3vxAqPtA

A QUIET VOICE, A STILL SOUL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

As I have practiced it, photography produces pleasure by its simplicity. I see something special and show it to the camera. A picture is produced. The moment is held until someone sees it. Then it is theirs. -Sam Abell, STAY THIS MOMENT, 1990

The voyage and the vehicle: Sam Abell’s classic image of a canoe on Maine’s Allagash River, the cover image for his book, 1990’s Stay This Moment.

THERE ARE PHOTOGRAPHERS THAT ARE SO AMAZINGLY ADVANCED that they make their images, wrought with love, ferocity, daring, and single-minded purpose, seem not merely visionary but inevitable. We see what they have brought us and exclaim, “of course”, as if theirs is the only way this message could possibly have been crafted, as if its truth is so self-evident that to have to formally recognize it is almost needless overkill. We confirm and validate that, for these pictures, the machine has truly been placed in the service of a soul, and one which writes fluently while we stumble with numb gestures.

One such soul resides in the work of Sam Abell.

If his name doesn’t roll off the top of your tongue alongside those of the obvious Jedi knights of photography, it’s because, for most of his forty-plus year career, he has kept a lower profile than Amelia Earhart, producing amazing work beneath the masthead of National Geographic magazine along with a host of other special commissions. When Sam came to to Geographic in 1967 as an intern, he already had four years of “hard” experience producing images for the University of Kentucky’s school of journalism to his credit, but the magazine’s photo editor, Robert Gilka, was hesitant to hire him, worried that his work was “too artistic”, too personal in its beauty to survive in the service of journalism.

For Abell, it’s all about the patience. How long do you wait for the horse to wistfully glance over his shoulder? As long as it takes…..

With help, Sam Abell learned the balance for getting the facts for stories and getting the truth implied in their locales. Even when those stories’ words shouted with urgency, Sam’s notes were always on the soft pedal. Their poignancy fades in and builds, rises to your attention and then rivets it in place. Writing in his 1990 collection Stay This Moment, Abell declares that the test of great pictures is that “they cannot be memorized”. Small wonder that he began, early in life, to pursue a career on the cello. Smaller wonder yet is that the patience of that instrument is “heard” in the music of his pictures.

Always, a human context. Sam Abell capture of the iconic buildings of the Kremlin, framed by ripening fruit and lace curtains.

Even more muted than the images Sam creates is his technical approach to taking them. For much of his early career, he shot breathtaking landscapes with a simple 35mm camera, often a Leica reflex or rangefinder, mounted with standard or “normal” lenses ranging from 28 to 35mm, generating the least amount of distortion and rendering the most natural relationship of sizes and distances. For years, the most advanced tools in his bag were a sturdy Gitzmo tripod and the slowest, richest films he could find, frequently Kodachrome 25 and 64. The tripod delivered the stability needed to produce slow, sensual exposures; the ‘Chrome delivered texture and nuance beyond the power of hand-held shots. However, the most vital weapon in Abell’s arsenal is his astonishing patience, the wisdom, which flies in the face of traditional journalism photography, to wait for the story in a picture to slowly unfold, like the petals of a flower. Some of the best images Abell placed in National Geographic over the years took nearly a year to create. It happens when it happens, and once it does, God is it worth it.

The number of printed collections of Sam’s work are few and far between, given his enormous output, but diligence rewards the curious. Among the most available of them is the collaboration undertaken with historian Steven Ambrose, Lewis & Clark: Voyage of Discovery ( 2002), for which Sam created images of the surviving sections of the legendary explorers’ trail to the Pacific; Amazonia (2010), an essay on the kind of delicate ecosystems that are vanishing from the earth; and Life of a Photograph (2008), an examination of how his most famous pictures were built, stage by stage. And, of course, there is the luxuriant (and hopelessly out-of-print) Stay This Moment (1990), the companion book to his mid-career exhibition at New York’s International Center for Photography. Buy it in a used book shop, grab it on e-Bay, scour your local library, but find this book.

More importantly, find Sam’s work…any of it…and savor every detail. For copyright protection purposes, I have deliberately kept the illustrations in this article constrained to minimal resolutions. Find the real stuff, and see what Abell’s amazing sweep and scope can do at full-size. This blog is chiefly about how I, as a rank amateur, struggle with my own creative conundrums. But it is also about knowing what teachers to bend toward. Sam Abell, who literally teaches in mentor programs all over the country, has a powerful gift to impart. “What is right?”, he asked in 1990. “Simply put, it is any assignment in which the photographer has a significant emotional stake.” He also emphasized an important distinction (one of my favorites) in his remarks to a young photography student. Don’t say, he said, I took this picture.

Say instead, I made this picture.

Of course.

Thoughts?

Related articles

- Sam Abell Interview (keronpsillas.com)

- The Life of a Photographer – Sam Abell (billives.typepad.com)

BIG STORY, LITTLE STORY

Which image better conveys the romantic era of the Queen Mary, the wide-angle shot along the promenade deck (above), or a detail of lights and fixtures within one of the ship’s shops (below)?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE VERY APPEAL THAT ATTRACTS HORDES OF VISITORS to travel destinations around the world, sites that are photographed endlessly by visitors and pilgrims alike, may be the same thing that ensures that most of the resulting images will be startlingly similar, if not numbingly average. After all, if we are all going for the same Kodak moment, few of us will find much new truth to either the left or right of a somewhat mediocre median.

In a general sense, yes, we all have “access” to the Statue of Liberty, the Grand Canyon, Niagara Falls, etc., but it is an access to which we are carefully channeled, herded, and roped by the keepers of these treasures. And if art is a constant search for a new view on a familiar subject, travel attractions provide a tightly guarded keyhole through which only a narrowly proscribed vantage point is visible. The very things we have preserved are in turn protected from us in a way that keeps us from telling our subject’s “big story”, to apprehend a total sense of the tower, temple, cathedral or forest we yearn to re-interpret.

More and more, a visit to a cultural keepsake means settling….for the rooms you’re allowed to see, the areas where the tours go, the parts of the building that have been restored. Beyond that, either be a photographer for National Geographic, or help yourself to a souvenir album in our gift shop, thank you for your interest. Artistically speaking, shooters have more latitude in capturing the stuff nobody cares about; if a locale is neglected or undiscovered, you have a shot at getting the shot. Imagine being Ansel Adams in the Yosemite of the 1920’s, tramping around at will, decades before the installation of comfort stations and guard rails, where his imagination was only limited by where his legs could carry him (and his enormous and unwieldy view camera, I know). Sadly, once a site has been “saved”, or more precisely, monetized, the views, the access, the original feel of its “big story” is buried in theme cafes, commemorative shrines, info counters, and, not insignificantly, competition with every other ambitious shooter, who, like you, wants a crack at whatever essences can still be seen between the trinkets and kiosks.

On a recent visit to the 1930’s luxury liner RMS Queen Mary, in Long Beach, California, I tried with mixed results to get a true sense of scale for this Art Deco leviathan, but its current use as a hotel, tour trek and retail mall has so altered the overall visual flow that in some cases only “small stories” can effectively be told. Steamlined details and period motifs can render a kind of feel for what the QM might have been before its life as a kind of ossified merchandise museum, but, whereas time has not been able to rob the ship’s beauty, commerce certainly nibbles around its edges.

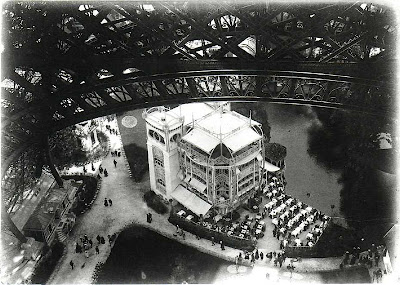

Sometimes you win the game. I recently discovered the above snapshot of the Eiffel Tower, taken in 1900 by the French novelist Emile Zola, where real magic is at work. Instead of clicking off the standard post card view of the site, Zola climbed to the tower’s first floor staircase, then shot straight down to capture an elegant period restaurant situated below the tower’s enormous foundation arches. And although only a small part of the Eiffel is in his final frame, it is contextualized in size and space against the delicate details of tables, chairs, and diners gathered below, glorifying both the tower and the bygone flavor of Paris at the turn of the 20th century.

Perhaps, for a well-recorded destination, the devil (and the delight) is in the details. Maybe we should all be framing tighter, zooming in, looking for the visual punctuation instead of the whole paragraph. Maybe all the “little stories” add up to a sum greater than that of the almighty master shot we originally went after. Despite the obstacles, we must still try to dictate the terms of engagement.

One image at a time.

Thoughts?

LOMO MOJO

A perfectly average handheld interior shot taken without flash in 2012. What is amazing, to an old geezer like myself, is how completely impossible it would have been, back in the day, to capture even this modest shot with the very same type of toy plastic camera now being sold to “lomography” enthusiasts and marketed as “hip”. Light leaks and color streaks do not an image make.

I AM INTERESTED MOST IN WHAT MAKES PEOPLE WANT TO TAKE PICTURES, as well as what makes them take the best ones. In that spirit, I have been recently re-examining the decade-long debate on the trend known as lomography, or the use of plastic bodied, low-tech toy cameras as serious imaging instruments. In renewing the impact of “lomo”, with its rudimentary shutter speeds and fixed-focus meniscus lenses, I have pored over four bazillion angry diatribes by those who condemn the cameras’ extreme technical limits and dismiss their enthusiasts as trendy phonies. I have also tracked its rabid defense by ardent users who celebrate lomo cameras as a way back to a kind of artistic innocence, a return to a photographic Eden in which we all shoot with our hearts instead of our heads. At the end of it all, does it matter what anyone thinks about how we take pictures if something, anything comes along to want them to take more of them? Probably not, and I certainly can’t decide the issue, if it needs deciding at all. Still, a brief re-examination of the whole concept, as I see it, might be worth a run-through. Your mileage may vary…

And, yes, before we proceed, I freely admit that a few world-class photos have been taken with cameras that are one step above drawing the image yourself with a crayon, just as a few amazing canvasses have been created by artists who hurl paint the way a monkey flings poo. I leave it to your discretion whether these accomplishments are vindication of a great vision, or happy accidents granted by the randomness fairy.

Backstory section: as a lifelong shooter, I enthusiastically began taking pictures with the very types of cameras which lomo fans so highly prize. This was dictated purely by economics, not art. It’s fair to say that, with the opening of every new packet of prints that arrived from the processor in those days, I spent more time cursing the smotheringly narrow limits of my light-leaky box and its take-it-or-leave-it settings than I spent cheering the results as some kind of creative breakthrough. I knew what real cameras could do. My father had a real camera. I had a toy, a toy which would betray my best efforts at breathtaking captures pretty much at will.

I didn’t feel avant-garde. I didn’t feel edgy.

I felt like I wanted a real camera.

Turns out that the manufacturers of my Imperial Mark XII, along with the Holga, the Diana, and other constellations in the lomo firmament, eventually came to the same conclusion. Many of their cheap products were made in the underdeveloped economies of iron-curtain countries.They cranked these babies out with the chief object of making a quick buck on undemanding first-time buyers and children. There was no attempt to market these clunkers as serious instruments; they were the fixed-focus, plastic-lensed equivalent of a bootlegged Dylan album taped off the mixer board. Eventually, these companies went on to other ways of separating the rubes from their rubles.

Now factor in the effect of time, nostalgia and (wait for it) ironic marketing. In the beginning of the digital age, photography arrives at a crossroads. Film is being challenged, if not falling under actual attack. Photography seems, to some, to have surrendered to a soulless technology rather than the “warm”, “human”, “hands-on” feel of analog picture-making. And as for the black arts of post-processing, the digital darkroom begins to be demonized only slightly less than the clubbing of baby seals. The unexpected, the unforseeable, the random begins to be attractive, simply because it spits in the eye of all this robo-gearhead slide toward pixels and light sensors.

A longing for a simpler time is observed among the young, who long to dress in forty-year old clothes and who regard vinyl records as more “authentic” than digital audio, not in spite of the scratches, but because of them. Film photography and its worst accidental artifacts becomes “retro” product, to be marketed through trendy boutiques and vintage stores. The sales message: anyone can take a picture (true, actually). The box isn’t important (less true). None of it’s important (outright lie). Shoot from the hip! Look, it made a weird rainbow streak on the picture, isn’t that cool?

Cool at a premium cost, as well. Cameras that went for $5.00 as toys in the ’60’s are now topping $100.00 for the same optics and defects in 2012, with one principal, cynical difference; in the newly produced cameras, the optical defects are being engineered in on purpose, so that every frame comes saturated not only with garish color but attitude as well. Every click produces a tic. This kind of salesmanship makes Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans seem absolutely honorable by comparison.

Tolerance disclaimer: can great art be created with a rudimentary tool? ABSOLUTELY. Cave dwellers made wheels good enough to move their carts to market well before Sears Craftsman came on the scene. I can make a sort of painting using dried sticks, but somehow I suspect that a supple, tapered brush gives me more fine-tuned control. In the field of combat, I can open someone’s airway with the shaft of a Bic pen (see your favorite M*A*S*H* re-run) but writing instruments are not, typically, the tool of choice in the operating rooms at the Mayo. We don’t use sealing wax to send love letters anymore, we don’t take the family horse on a Sunday jaunt to the county seat, and we don’t eat peas off a knife. Of course we could. But what is our motivation to do so?

The historic arc of photography bends toward technical development, not fallback. As soon as glass plates were developed, their limits implied the need for film. Once film first froze movement, we needed it to do it faster. No sooner had pinhole apertures allowed a picture to be crudely focused than the market cried out for dedicated glass to refine those pictures. And while many were just getting over the novelty of recording events in monochrome, some dreamed of harnessing all the shades in the rainbow.

Tolerance disclaimer #2: the only reason to use a technique or system is if it gives you the pictures you want. Once your dreams exceed the limits of that medium, however, it’s time to seek a better system. Prevailing over the limits of your medium because that’s all there is can be noble. However, there is no artistic triumph in deliberately using bad equipment to take great pictures. Lomo cameras may entice people to begin shooting, then move on once they outgrow the warps, distortions and flares that these toys produce. Thus the trend will at least have given them time to experiment and master the basics. But for the most part, for me,there are already far too many obstacles to making good pictures to allow the camera itself to be one of them.

Even in the name of cool.

Thoughts?

I WANT TO BE A PART OF IT…..

One belongs to New York instantly. One belongs to it as much in five minutes as in five years.

-Tom Wolfe

Old power, new power. The American Stock Exchange, a titan of the might of another era, stands in lower Manhattan alongside the ascending symbol of the city’s survival in another age, as the frame of WTC 1 climbs the New York sky. The tower, recently surpassing the height of the Empire State Building, will eventually top out, in 2013, at 1,776 feet. Single-image HDR designed to accentuate detail, then desaturated to black & white. 1/160 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 18mm.

THERE IS NO GREATER CANDY STORE FOR PHOTOGS than New York City. It is the complete range of human experience realized in steel and concrete. It is both a monument to our grandest dreams and a mausoleum for all our transgressions. It casts shadows that hide both joy and fear; it explodes in light that illuminates, in equal measure, the cracked face of the aged contender and the hopeful awe of the greenest newcomer. There is not another laboratory of human striving like it anywhere else on the planet. Period period period. Its collapses and soarings are always news to the observer. Bob Dylan once said that he who is not busy being born is busy dying. New York is, famously, always busy doing both.

I would give the greatest sunset in the world for one sight of New York’s skyline.

-Ayn Rand

Returning from Liberty Island and Ellis Island in November 2011, a packed tour boat’s passengers crowd the rail for a view of WTC 1, rising as the new king of the New York skyline.

This month’s announcement that the new WTC 1 (built on the site of the old 6 World Trade Center building, itself a rather short edifice) has finally surged past the height of the Empire State Building (a repeat champ for height, given the strange twists of history) is a bittersweet bulletin at best. Cheers turned to tears turned back into cheers. In the long-view, the inevitable breathe-in-breathe-out rhythm of NYC’s centuries-old saga, the site’s entire loop from defeat to defiant rebirth is only a single pulse point. Still, on a purely emotional, even sentimental level, it’s thrilling to see spires spring from the ashes. The buildings themselves, along with their daily purposes and uses, hardly matter. In a city of symbols, they are affirmations in an age when we need to remain busy being born.

Thoughts?

ALWAYS BE SHOOTING

Urban survivors or disposable legacy? Part of the world is always vanishing from view. What portions to visually preserve? And how best to tell these stories? 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 1000, 18mm.

PAUL DESMOND, LEGENDARY SAXOPHONIST for the Dave Brubeck Quartet, was famous for his wry replies to mundane questions from the press. Asked once “so, how are things going?”, he quipped, “Great. We’re playing music like it’s going out of style…..which, of course, it is.”

Beyond the cleverness of the statement, Desmond actually provided a corrolary to the ongoing state of photography. It is an art which is never “settled” into any final form, either in its mechanics or its aesthetic. Glass plates give way to roll film, which give way to digital storage, which will give way to..what? Recent trends in the forward edge of shooting hint at, among other things, bold new experiments in the direct exposure of chemically treated paper, minus lenses or shutters, resulting, in effect, in a camera-less camera. So now, what? A method so old that it’s new? So complicated that it’s totally simple? And where in these new crafts lie the art they might enable?

As image makers, we are really running down two parallel rails en route to obsolescence, since the world, as it can presently be seen, is passing away at the same lighting rate as our current means of documenting it. This is a constant for our art. When Eugene Atget recorded the last days of the Paris of the late 19th century, his methods for making the shots was fading out of fashion almost as quickly the dark, twisting streets he recorded. And when his protege, Berenice Abbott, undertook the same “mapping” of New York’s boroughs in the 1930’s (on assignment from various New Deal agencies), she, too was laboring against constantly improving methods for completing the book Changing New York, starting her massive project with a 60-pound view camera, and ending it with a new, lighter Rolleiflex miniature. She was also, understandably, racing against the wrecking ball of progress.

Worse, many places, such as the American southwest (where I live), hold the view that “old” is not “venerable”, but “in the way”….creating, for the shooter, a constant conundrum; what to visually archive, and in what way, and in what order?

The quiet death of Kodachrome, several years ago, proved a challenge for imagists the world over. If you were burning your last roll of this fabulous film forever, what shots would make your photographic bucket list? And how about expanding this scenario to include not just diehard “filmies”, but everyone? If there were an absolute deadline for imaging, a date beyond which no more pictures could be taken, ever, ever, what new urgency would inform your choices?

Sites like Ellis Island’s Great Hall have more than their share of caretakers. But how many other visual dramas will escape our viewfinders before they pass from the earth? 1/25 sec., f/6.3, ISO 100, 18mm.

It’s almost that dire already. Time hurtles forward and lays waste to everything in its path, including ourselves. Today, now, we are watching it erase neighborhoods, cities, forests, the shapes of nations, even the names of places. Even if we use our skills largely for cataloguing the general effect of these changes, we are nonetheless under the gun to fill our days with the grabbing of these fleeting glances. Even while we perpetually change how we capture, we must capture as much as we can, by any means available.

There is no mission statement stronger than the three words always be shooting. Because we are doing more than saving memories; we are, in fact, bearing witness. Whatever the subject, wherever we want to start chronicling the word around us, we need to be taking pictures.

Like they’re going out of style.

Thoughts?

WHEN ART SELF-CENSORS

IN ITS FIRST DAYS, photography took on the inward, personal aspect of painting, both in its selection of pictorial subjects and in its method of presentation, which was designed to legitimize the new science by aping the look of the canvas. Only by actively engaging the world and invading every corner of it in an outward search for truth or beauty did picture-making break free of the painter’s constraints. Once Matthew Brady’s stark images of the Civil War froze that conflict’s horror on glass, at least one leg of the photographer’s stool rested on a confrontation of reality.

In the 20th century, as shooters toggled between deliberate, arranged images and pure documentation, the “face” of the public became an unwitting tool in the artist’s toolbox. Human manifestations of delight, horror, revelation and ruin told the story of the new era even more graphically than the correspondent’s pen, creating some of the most indelible images of modern times. Indeed, there seemed to be an unspoken pact between the artist and his “prey” to the effect that their lives, like ours, could be endlessly recorded, interpreted, interrupted and enshrined for the sake of our “art”.

But is that era coming to an end? And, for photography, what lies beyond?

By agreeing to appear at a book fair and signing, public figures like Elmore James (author of Get Shorty and, 3:10 to Yuma, and consultant on the TV series Justified) more or less agree to allow their images to be recorded as part of the celebrity they have willfully undertaken. But what of everyone else? 1/40 sec., F/11, ISO 160, 300mm.

In recent years, both public and private institutions have begun to disallow photography in some venues that had historically been open to it, including retail stores, parks, malls and other previously “free” spaces. Some of this is the inevitable aftermath of our recent obsession with security, a kind of whoa-slow-down against the pervasive replication of all aspects of one’s identity. Perhaps, several gazillion camera phone snaps and gotcha YouTubes later, we have reached a tipping point of sorts, a world in which people desperately seek a firewall around their secret selves.

Even as certain nondescript individuals shamelessly seek the spotlight of reality shows and paparazzi-fed ego gratification, many more are feeling an unfamiliar new yen for shelter from the ubiquitous flash of fame. In such a time, the concept of commentary or “street” photography faces one of its most daunting challenges. What is permissible in an image, now? Are what were once the eloquently revealing truths of spontaneous snaps now a kind of voyeurism, a “reality porn” peek into peoples’ lives to which we have no right?

Without the harrowing chronicle of Dorothea Lange’s dust-bowl refugees, would we understand less of the horrific impact of the Great Depression? Was she underscoring an important message or exploiting her subjects’ suffering? Absent Larry Burrows’ grunt’s-eye-view of Vietnam for Life magazine, would we have missed a valuable insight into a war our government might just have gladly kept under wraps? We may have already reached the point where some of us, embarrassed for the intrusive nature of our craft, have begun to self-censor, to mentally de-select some images before we even shoot them. Such prior restraint may be the height of sensitivity, but it spells paralysis for art.

THE GLORY OF THE INVISIBLE

I thought of trying to capture the vastness of Manhattan’s Strand Bookstore in a single wide shot, but finally preferred this view, which suggests the complexity and size of the store’s labyrinthine layout. 1/40 sec., F/7.1, ISO 500 at 18mm.

THE FRAME OF AN IMAGE is the greatest instrument of control in the photographer’s kit bag, more critical than any lens, light or sensor. In deciding what will or won’t be populated inside that space, a shooter decides what a personal, finite universe will consist of. He is creating an “other” world by defining what is worthwhile to view, and he also creates interest and tension by letting the view contemplate what he chose to exclude. What finally lies beyond the frame is always implied by what lies inside it, and it is the glory of the invisible that invites his audiences inside his vision, ironically by asking them to consider what is unseen….in a visual medium.

Each choice of what to “look at” has, inherent in it, a decision on what to pare away. It is thus within the power of the photographer to make a small detail speak for a larger reality, rendering the bigger scene either vitally important or completely irrelevant based on his whim. Often the best rendition of the frame is arrived at only after several alternate realities have been explored or rejected.

Over a lifetime, I have often been reluctant to show less, or to choose tiny stories within larger tapestries. In much pictorial photography, “big” seems to serve as its own end. “More” looks like it should be speaking in a louder voice. However, by opting to keep some items out of the discussion, to, in fact, select a picture rather than merely record it, what is left in the frame may speak more distinctly without the additional noise of visual chatter.

“If I’d had more time”, goes the old joke, “I’d have written you a shorter letter”. Indeed, as I get older, I find it easier to try and define the frame with an editor’s eye, not to limit what is shown, but to enhance it. Sometimes, the entire beach is stunning.But, in other instances,a few grains of sand may more eloquently imply the beach, and so enable us to remember what amazing details combine in our apprehension of the world.

Thoughts?