SPLITTING THE DIFFERENCE

Really dark church, not much time. An HDR composite of just two exposures to refrain from trying to read the darkest areas and thus keep extra noise out of the final image. Shot at 1/15 and 1/30 sec., both exposures at f/5.6, a slight ISO bump to 200 at 18mm. Far from perfect but something less than a total disaster with an impatient tour group wondering where I wandered off to.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE MOST EXASPERATING WORDS HEARD ON VACATION: Everyone back on the tour bus.

Damn. Okay, just a second.

Now. We’re going NOW.

I’ve almost got it (maybe a different f-stop….? …..no, I’m just standing in my own light….here, let’s try THIS….

I mean it, we’re leaving without you.

YES, right there, seriously, I’m right behind you. Read a brochure will ya? Geez, NOTHING’S working…….

Sound remotely familiar? There seems to be an inverse proportion of need-to-result that happens when an entire group of tourists is cursing your name and the day you ever set eyes on a camera. The more they tap their collective toe wondering what’s taking so looooong, the farther you are away from anything that will, even for an instant, give you a way to get on that bus with a smile on your face. It’s like the boulder is already bearing down on Indiana Jones, and, even as he runs for his life, he still wonders if there’d be a way to go back for just one more necklace….

Dirty Little Secret: there is no such thing as a photo “stop” when you are part of a traveling group. At best it’s a photo “slow down” unless you literally want to shoot from the hip and hope for the best, which doesn’t work in skeet shooting, horseshoes, brain surgery, ….or photography. Dirty Little Secret Two: you are only marginally welcome at the tomb or cathedral or historically awesome whosis they’re dragging you past, so be grateful we’re letting you in here at all and don’t go all Avedon on us. We know how to handle people like you. We’re taking the next delay out of your bathroom break, wise guy.

A recent trip to the beautiful Memorial Church at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California was that latest of many “back on the bus” scenarios in my life, albeit one with a somewhat happy outcome. Dedicated in 1903 by the surviving widow of the school’s founder, Leland Stanford, the church loads the eye with borrowed styles and decorous detail from a half-dozen different architectural periods, and yet, is majestic rather than noisy, a tranquil oasis within a starkly contemporary and busy campus. And, within seconds of having entered its cavernous space as part of a walking campus tour, it becomes obvious that it will be impossible to do anything, image-wise, other than selecting a small part of the story and working against the clock to make a fast (prayerful) grab. No tripods, no careful contemplation; this will be meatball surgery. And the clock is ticking now.

So we ducked inside. With many of the church’s altars and alcoves shrouded in deep shadow, even at midday, choices were going to be limited. A straight-on flash was going to be an obscene waste of time, unless I wanted to see a blown-out glob of white, three feet in front of me, the effect of lighting a flare in a cave. Likewise, bumping my Nikon’s ISO high enough to read a greater amount of detail was going to be a no-score, since the inner darkness was so stark, away from the skylight of the central basilica dome, that I was inviting enough noise to make the whole thing look like a kid’s smudged watercolor. No, I had to find a way to split the difference; Show some of the light and let the darkness alone.

Instead of bracketing anywhere from 3 to 5 shots in hopes of creating a composite high dynamic range image in post production, I took a narrower bracket of two. I jacked the ISO for both of them just a bit, but not enough to get a lethal grunge gumbo once the two were merged. I shot for the bright highlights and tried to compose so that the light’s falloff would suggest the detail I wouldn’t be able to actually show. At least getting a good angle on the basilica’s arches would allow the mind to sketch out the space that couldn’t be adequately lit on the fly. For insurance, I tried the same trick with several other compositions, but by that time my wife was calling my cel from outside the church, wondering if I had fallen into the baptismal font and drowned.

Yes, right there, I’m coming. Oh, are you all waiting for me? Sorry…..

Perhaps its the worst kind of boorish tourism to forget that, when the doors to the world’s special places are opened to you, you are an invited guest, not some battle-hardened newsie on deadline for an editor. I do really want to be nice. However, I really want to go home with a picture,too, and so I remain a work in progress. Perhaps I can be rehabilitated, and, for the sake of my marriage, I should try.

And yet.

Related articles

- The Ultimate Guide to HDR Photography (pixiq.com)

BEYOND THE THING ITSELF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU NO DOUBT HAVE YOUR OWN “RULES” as to when a humble object becomes a noble one to the camera, that strange transference of energy from ordinary to compelling that allows an image to do more than record the thing itself. A million scattered fragments of daily life have been morphed into, if not art, something more than mundane, and it happens in an altogether mysterious way somewhere between picking it and clicking it. I don’t so much have a list of rules as I do a sequence of instincts. I know when I might have stumbled across something, something that, if poked, prodded or teased out in some way, might give me pleasure on the back end. It’s a little more advanced than a crap shoot and a far cry from science.

With still life subjects, unlike portraits or documentary work. there isn’t an argument about the ethics or “purity” of manipulating the material….rearranging it, changing the emphasis, tweaking the light. In fact, still lifes are the only kinds of pictures where “working it” is the main objective. You know you’re molding the material. You want to see what other qualities or aspects you can reveal by, well, kind of playing with your food. It’s like Richard Dreyfuss shaping mashed potatoes into the Devil’s Tower.

If I have any hard and fast rule about still lifes, it may be to throw out my trash a little slower. I can recall several instances in which I was on my way the garbage can with something, only to save it from oblivion at the last minute, turn it over on a table, and then try to tell myself something new about it from this angle or that. The above image, taken a few months ago, was such a salvage job, and, for reasons only important to myself, I like what resulted. Hey, Rauschenburg glued egg cartons on canvas. This ain’t new.

My wife had packed a quick fruit and nut snack into a piece of aluminum foil, forgot to eat it, and brought it back home in her lunch sack. In cleaning out the sack, I figured she would not want to take it a second day and started to throw it out. Re-wrapped several times, the foil now had a refractive quality which, in conjunction with window light from our patio, seemed to amp up the color of the apple slice and the almonds. Better yet, by playing with the crinkle factor of the foil, I could turn it into a combination reflector pan and bounce card. Five or six shots worth of work, and suddenly the afternoon seemed worthwhile.

I know, nuts.

Fruits and nuts, to be exact. Hey, if we don’t play, how will we learn to work? Get out on the playground. Make the playground.

And inspect your trash as you roll it to the curb.

Hey, you never know.

Thoughts?

ASKING THE MOUNTAINS TO SAY “CHEESE”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK IS A SUPREME PARADOX FOR A SHOOTER. On one hand, it has never been technically easier to simulate the texture and range of tones that were hard-won miracles for its guardian angel, Ansel Adams. On the other, the very act of visiting the park has never presented a more severe barrier to the kind of mental and emotional commitment to picture making that was, to him, a constant.

The original mission of this blog is to share creative successes from amateur to amateur, but also to name the problems which restrict us to taking, instead of making, pictures. Yosemite, historically the proving ground for photographers the world over, also presents one of these problems.

Adams had to suffer, slog, hike, and persevere to set up his visions, all the while wrestling with a technology that punished the slightest miscalculation. The park itself presented a rugged challenge to him as well in the early 20th century, as its greatest vistas were not just a minivan jog away and its best treasures resisted his inquiring eye. So how come his pictures are so much better, still, than anything most of us can deliver in an age of ultimate simplicity, ease, and access?

There is a disturbing statistic quoted by the park service, that the average visitor to Yosemite is actually in the park for a grand total of two and a half hours. Not exactly the time investment that a photographic subject of this scope warrants. We also tend to enter the park in much the same way, stop by a predictable list of features, and take most of the same “money shots”. We all know where the good stuff is, and it seems to be irresistible to offer up our “take” on the craggy face of El Capitan, the serene power of the Mariposa Grove (with its astonishing giant sequoias), or the obligatory capture of a waterfall….hell, any waterfall. And yet….I can’t be the only one who has come home from vacation to find that my pictures are just….okay. Overwhelmingly…..non-sucky. Stunningly….passable.

Adams’ life’s work, a mutual exchange of energy in which he and Yosemite were creative partners in the deliberate making of images, is, for us, a re-creation, a simulation, the photo equivalent of karaoke. Just like many lounge lizards “kinda” sing like Sinatra, too many of us “kinda” shoot pictures like Ansel. For Adams, photography was like asking the wilderness to dance. For us, it’s like asking the mountains to say “cheese”.

Part of his mission was showing us what a treasure we had, but he might have sold the product too well. Part of the Yosemite that spoke to him is gone, compromised into tameness by sidewalks,snack bars, and gift shops. Worse, much of what we do choose to record of it is done in quick stops off the tour bus, stolen moments before the kids get too tired , and the rabid urgency of God-let’s-hurry-up-we-have-three-more-places-to-hit-today. Indeed, park officials laughingly refer to people who drive in and out of the park’s main areas without even emerging from their cars, bragging that they “did” Yosemite, like a ten minute rock wall climb at REI, squeezed in before a trip to the food court.

The Ansel Adams Gallery, which has operated in the park for more than a century now, certainly features fresh visions by new artists who are still re-interpreting the wonder, still managing to say something unique. But many of our cameras will betray how little of our selves are invested behind the viewing screen. Adams’ work resonates through time because we recognize when someone has poured part of their soul into the creative cauldron. And certainly, if we are honest, we also know when that ingredient is missing.

“I want to see your face in every kind of light” goes the old love song lyric. Being in love with a woman, an idea, anything, demands time, deliberation. To see the object of one’s affection in all light, all seasons, all moods and tempers, is more of a pact than many of us are willing to make. The pictures we bring back from many places may not be lessened in their impact by this fact. But Yosemite is not “many places”, and she will not give up her secrets to just anyone. Fortunately, if we care, we can return and try again to do more than merely tattoo pixels onto a sensor. That has always been the promise of photography, that you can redeem your myopia from one day by re-thinking, re-feeling on another. But it means changing the rules of engagement with our subject. For those of us who cannot or will not do that, the world will not stop spinning, and, in fact, we will chalk up many acceptable images along the way, but Ansel will always be the one among us who really understood the magic, and discovered how to conjure it at will.

Related articles

- What’s black & white, famous, and coming to Peabody? (hangwithbigpictureframing.com)

- A Weekend in Yosemite (theepochtimes.com)

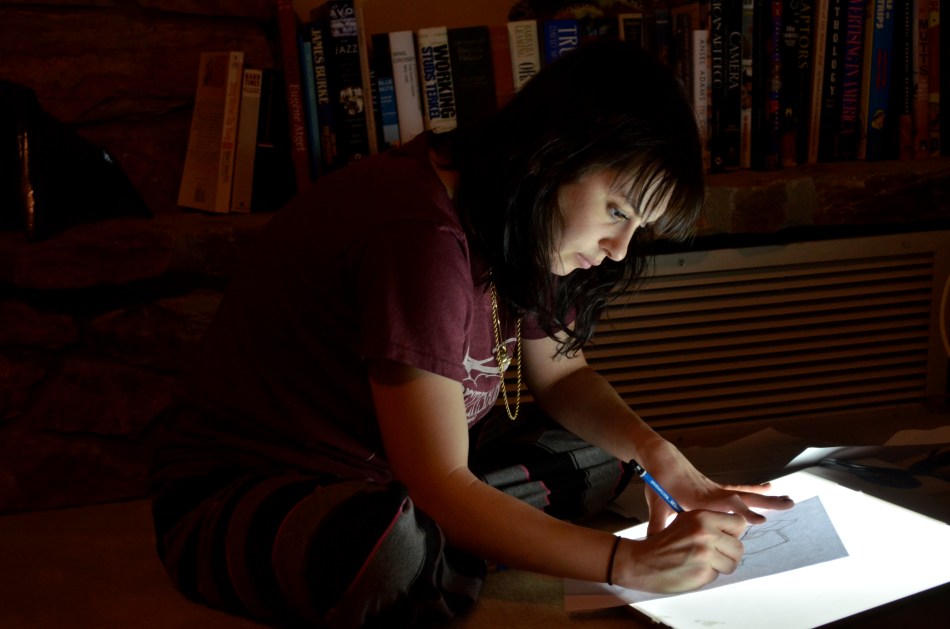

GLO-SCHTICK

Sometimes just a bit is just enough. A bump up to ISO 640 kept me fairly free of noise and allowed me to use the screen’s glow as my only light source. 1/30 sec., f/5.6 at 52mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE BEST TECHNIQUE is one that does not scream for attention like a neon t-shirt emblazoned with the phrase LOOK WHAT I DID.

Now, of course, we are all messing around backstage, working hard to make the elephant disappear. We all manipulate light. We all nudge nature in the direction we’d prefer that she go. But what self-respecting magician wants to get caught pulling the rabbit out of a hole in the table?

I recently had the perfect low-light solution handed to me as I watched a young designer working in a dim room, and, thankfully, only marginally aware of my presence. “Lighting 101” dictated that, to get a sense of her intense concentration, I send the most important light right to her face.

Turns out, a light tracer screen, in a pinch, makes a perfect softbox.

Better yet, the light from the screen thinned out and dampened after it traveled left past her shoulders, leaving just enough illumination to keep the rest of the frame from falling off completely into black, making the face the lone story-teller. An ISO bump to 640 and a white balance tweak were enough to grab the best of what the screen had to give. At this point in the “gift from the gods” process, you click, and promise, in return, to live a moral life.

Sometimes you don’t have to do anything extra to make a thing look like it actually was. That’s better than finding a hundred-dollar bill on the street.

Well, almost.

What was your best light luck-out?

“WHAT” IS THE QUESTION

ONE OF THE MOST FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS of shooters is, “what’s that supposed to be?”, usually asked of any image that is less obvious than a sunset shot of the Eiffel Tower or a souvenir snap of Mount Rushmore. You may have found, in fact, that the number of times that the question is asked is directly proportional to how intensely personal your vision is exercised on a given project. As much as the hidden aspects of life fascinate us, the obvious recording of familiar objects soothe the eye, like a kind of ocular comfort food. The farther you wander in your own direction as a photographer, the greater journey you also ask of your viewers. Sometimes the invitation is taken. Sometimes you must face “the question”.

What’s that supposed to be?

How, actually, in a world shaped by our own subjective experience, an image is “supposed” to be anything is a little baffling. It’s probably safe to say that what we present, as artists is probably supposed to be the view as one’s mind filters it through his or her accumulated life. When we use the camera as a mere recorder, it may make it easier, presenter-to-viewer, to agree on that image’s terms of engagement, but that may or may not reveal what we actually felt about when creating it. If I use the same three colors to render a picture of the American flag as everyone else uses, I may get into fewer arguments about how appropriate the resulting image is, but then, I don’t get to open up the discussion to any other conceptions of that flag. Back in the first days of the environmental movement, the simple use of green on the original, Old-Glory-derived ecology flag suggested an alternative way of being American, of living your life. As I recall, some viewed the design as sacrilegious, while others embraced it as liberating.

Over 150 years after the first photographs were regarded as a threat to the painter’s domain, we are still most at ease with pictures that ape the painting’s method for framing the world. Oddly, it is always outlaws and amateurs that break free of these pictorial chains first; the professionals must protect the turf they have so carefully mapped out for themselves in the mainstream. There remains, then, an ongoing battle over what should or should not be called a “picture”. Abstractions, arranged or perceived patterns, even selected details or drastic re-imaginings of small parts of the so-called “actual” world must always fight for their place at the table alongside the technically accurate mirroring of easily named subjects. We still regard that which is realistic as being the most real, and the most worthy of praise.

Cactropolis, 2011. Three bracketed shots about a half-stop apart combined into an HDR composite. CLICK TO ENLARGE.

To want to show something for its own sake on our own terms is to move into more personal territory, and hence onto shakier ground for critical evaluation, but occasionally we strike a balance between what people want to see and what we must show. In the above image, I only wanted to focus attention on an arrangement that was a very small and visually ignored accent along a heavily travelled public street. An unsung landscaper’s arrangement of tiles, gravel, paving rock, and succulent plants, was in plain view, and yet, at only a few inches in height, easily missed by the thousands of daily passersby speeding along the street. To me, when framed close to ground level, it resembled a kind of desert cityscape, blocks of abstract skyscrapers, a cactus metropolis, and that’s how I tried to frame and process it. Of course, it us, after all, just a pattern, and anyone who looks at the image can fill in their own blanks with impressions that are just as valid as my kind of toy idea.

The vital point is that no one else’s take on your dream can be wrong, just because it differs with yours. Art is not a science, which is why we don’t become photographers, or as the word implies, “light writers” just by pushing a button.

We become photographers by pushing everyone’s buttons.

What is it “supposed to be”? You tell me, and I’ll tell you.

Thoughts?