A CLIENTELE OF ONE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MAN’S NEED FOR THE APPROVAL OF HIS TRIBE, as envisioned in photographs, is one of the great unifying themes of the visual arts. We make pictures about how we need each other, how we struggle to maintain an identity within this or that group, how we qualify for membership in the human club. Strangely, however, it is the need of the individual to shine or to distinguish itself from the masses that gives art its voice and authority. We can’t do honest creative work by merely miming everything that has gone before.

Which begs the question, why do we strive, in social media, for endless approval of the pictures we make?

Not only do we want our pictures seen (an urge that could actually lead to growth or enlightenment), we crave for those who see them to approve of them. In all too many cases, we allow the value or worthlessness of a photograph to hinge on whether we can chalk up a requisite number of “likes”, thumbs-ups, or stars for it. Many photographers who have never entered any kind of formal art competition judged by like minds readily submit their ideas to a vast sea of unseen jurors in some increasingly needy quest for validation. But art doesn’t get done that way, and producing pictures for anyone outside of a clientele of one is the very opposite of creativity.

Making any kind of art means walking your own path.

The trap inherent in all this hunger after “likes” is that it is progressive, like any other addiction. The amount of approval one gets today becomes the minimum baseline for the amount of it that will satisfy us tomorrow. Even though our art can never ascend on a steadily uphill plane without dips and reverses, we grow to expect that the tide of approbation for it will continue skyward forever, or else, who are we? Art that is based on popular approval becomes mere pandering, putting our work at the service of whatever will make the crowd smile on a given day. That leads to repetition, imitation, and eventually self-parody. And it’s the end of pictures that build or feed the soul.

As the first Age Of A.I. threatens the very concept of authorship, challenging what makes an image “ours”, photographers must be more convinced than ever before of the value of their personal art. That means that we need to be content within ourselves, not endlessly second-guessing the vacillations of public taste. Make your pictures for yourself. If their stories are true and universal, others will find them. Chasing after likes is running away from what qualifies a photo as a narrator in the first place, and that resides only in the person who created it.

TALISMAN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WEEKS AGO, DURING WHAT WOULD PROVE TO BE MY FINAL VISIT TO MY MOTHER, my sister, who had long served as her in-house caregiver, presented me with something of a family relic; a small porcelain figurine of Pinocchio that I had not seen since my toddler days. I still don’t know if she simply found it in some cranny of the family home, or whether Mother, who certainly knew she was gravely ill, had somehow deputized her to give it to me. I didn’t ask any questions, but quickly secured the little guy in my shaving kit, where he would nap on the way back home.

I’m even unclear as to how the little statue, just over an inch high, even made it into our first house, that is, the first house I remember as a child. Mother liked to post it on the packed soil around various potted plants in our living room, and may have even moved it around as a sort of game for me. I had a tendency to want to own Pinocchio for myself, and frequently slipped him into my small hand, studying his little face, his red gloves, his green Tyrolean cap. And now, after all these years, here he was back again, staring at me from a curio shelf, a souvenir of a life that was all shadows and a Mother that was about to become, well, something that dwelled in them.

In these first days following her death, the figurine has come to symbolize something that I wanted my camera to help…explain. I wanted an image that captured the magic and mystery of the object, to make it appear suspended in space and time, floating between memory and prophecy. The fact that the figure was of a toy who yearned to be a real boy struck me as mystical in a way, and I dreamed of making a picture that suggested that. But the mystery remains. Why does he return to me now, at the nexus of an irretrievable past and an unknowable future? Am I the toy that once again must aspire to becoming “real”? And can I, or anyone, ever make a picture of all that?

In these first few strange days without my mother in the world, even though I was blessed to have her for nearly a century, all things seem equally real and unreal. Maybe this little toy/boy has come to me just now for some reason.

Or maybe it’s mere sentiment, fantasy.

Either way, I’m glad he’s home.

TOWARD A MESSIER MOI

By MICHAEL PERKINS

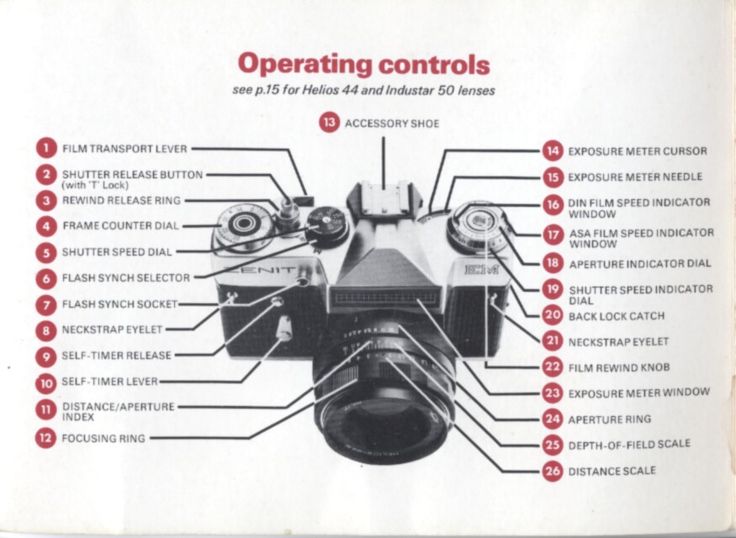

I SPENT THE FIRST TEN YEARS OF MY PHOTOGRAPHIC LIFE in a more or less constant state of frustration, given that I had not mastered the mechanical basics of the art, measuring the “success” of my pictures only in that light. The “if only’s” ruled my thoughts; if only I had a better camera; if only I could get more even results; if only I could make my subjects look more “realistic”. Everything in those early years….personal emotion, vision, impact….was subordinated to a worshipful pursuit of technical precision. I shot like I was recording illustrations for a travel brochure.

Miraculously, the digital age has eliminated a lot of the risk that used to confound me and other shooters. In such an era, we, more often than not, get some kind of usable picture, freer than ever before from technical defects. In this way, our cameras protect us from our messier selves. But that, in turn, can lead us to another kind of failure, one in which we neglect the unpredictable but potentially exciting irregularities that stamp our personalities onto our images. In recent years, almost as a kind of correction or recoil, photogs in the Age Of Guaranteed Outcome have sought to retro-fit photographs with the feeling that this is not a perfect process. This shift has been seen in several trends: the re-introduction of lo-fi film cameras, which actively seek the accident or the tech fail; post-processing apps which aim not merely to evoke the look of other eras, but to illustrate that uncertainty and imprecision are key parts of memory; and art glass and instant photography that romanticize the random.

I have come full circle in these times, opting occasionally to overrule reality in pursuit of feeling. The master shot of the above image, taken at some distance, originally smoothed out the rougher textures of the urban rooftops, or at least those that I saw in my mind. The un-retouched “reality” of the subject was too pretty, if you will, straight out of the camera. A quick HDR conversion, however, brought every brick and stone into gritty relief; meaning that I had to deliberately re-flaw the image to make it truer, saying a polite “no thanks” to the “actual” look delivered by my advance device. I needed some wrongness to be put back in the scene to make it right.

When we express ourselves with a minimum of even well-meaning interference between initial vision and final result, we produce a really inconsistent mix of correct and incorrect execution, making our hits nearly as mysterious as our misses. But this personal autographing of our images is important, more so than ever before, especially as we peer into the dark, spooky cave of A.I. and wonder how to keep our work truly ours. One thing is sure; authorship, properly asserted, cannot be counterfeited or aped, and photographs can never merely be about a mixtures of processes. It’s in the sloppy soup of the actual human brain that anything pretending to true “art” resides, and that unique product can never be assimilated or simulated.

ALWAYS KEEP ON THE SUNNY SIDE (OR DON’T)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU RELISH VIEWING A LOT OF PHOTOGRAPHIC DISCUSSIONS THAT BEGIN with either “I always” or “I never”, enter “Do You Use Flash Photography?” into a search engine, stand back, and brace for impact. I check such forums on a fairly regular basis as I personally believe that, with fewer and fewer exceptions, we are generally entering the twilight of the flash era, and I am curious as to why the hangers-on still defend its use, exclusive of very special situations.

Hmm. Reading back that last sentence, it sounds as if I’m trying to start a grudge match of some sort. I am not. All I am doing, as a photographer of some fifty years’ experience, is relating my own experience and comparing it with that of others. I tend to see flash as a tool that once was needed by nearly everyone, which is much the same view I have of, say, tripods. Both tools were once much more essential to good results than they are today, simply by virtue of the evolving acuity and sensitivity of current tech. Cameras cannot absolutely copy the eye in all its operations, but increasingly intuitive functions have been engineered across more and more shooting scenarios, including much faster and more precise evaluation of things like contrast and color temperature. As a result, the benefit of flash is often counter-weighted against all the things that can go wrong with flash (including bulk, expense and difficulty of consistent results), leading people like myself to go for years at a space without ever shooting a single frame with it.

Today’s cameras have drastically redefined the phrase “adequate light”. Is flash photography headed for the scrap heap of history?

The signs of change abound: wedding shoots, once a key domain for flash, are increasingly flashless upon the insistence of either the bridal party or venues that simply don’t allow it; more full-service cameras are being marketed with no flash hot shoe whatsoever, achieving the needed thirst for additional light with larger sensors and greater ISO ranges; and while cellphone cameras still default to the use of flash, the chance to opt out of it altogether has been offered for more than a decade now.

Nikon’s global ambassador (and shooter extraordinaire) Joe McNally once defined “available light” as “any damn light that’s available” and he has taught millions how to keep flash on something of a short leash, using it to balance or enhance rather than to actually serve as primary illumination. For me (and that’s the only person I can speak for), the meeting of advanced technology and a better understanding of how all light works has reduced the number of must-flash situations to a short list. That said, many people continue to produce miracles using it, meaning that it may never completely wink ot of existence.

IN CHARGE OF THE MAGIC

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU FEEL IT THE FIRST TIME YOUR GRANDCHILD HAS TO HELP YOU access an app or activate a new toy, that uneasy fear that you are falling behind the latest technological wave….that the bus is leaving the terminal, and you ain’t on it. And of course, you, along with everyone else, tend to interpret such apprehension as a direct by-product of “aging”, but, is it really? Experience would seem to prove that, whatever our stage in life, we are estranged or intimidated by all kinds of processes or inventions; the only real issue is whether we merely use the magic without understanding it (turn the switch on and the gadget just works) or, by our level of engagement, actively pair our own energy with the magic, actively partnering with it.

I believe that’s the reason the technical end of photography has continued to hold its central appeal to me over a lifetime, not only because I apprehend, at least in general, how it works, but also because I see a part for myself in helping make it work. The media analyst Marshall Mcluhan famously said that all media were extensions of the human body. The wheel was an extension of the foot; the loudspeaker was an extension of the ear; and the camera was an extension of the eye. Photography is a mechanical process that is initiated only after an impression or idea is formed in the mind and eye. Its recording capacity is deaf and dumb until a concept propels and shapes it. Its interpretive process is completely non-existent except at the service of the eye’s guidance. Even the most automatic, “intuitive” cameras, such as those in cellphones, can never be set on full “automatic”. The computer has the means to be easily programmed, but the program itself, the code that is written between the shooter’s ears, must be supplied first.

There are many places in which my connection to tech is that of a user only, a relationship in which the magic arrives fully formed and I merely consume it. Snap on a light, open up the water tap. But with a camera in my hand, I am in a collaboration. Neither the tech nor I have the means to reach our ends without the other. That makes the workings of a lens and shutter sacred to me, since they are the pens I write with, the crayons I draw with, the extensions of myself. Nothing is automatic, and nothing is guaranteed, except that I am always in charge of the magic.

NEVER SAY ALWAYS SAY NEVER

A texture and feel beyond the real: An iPhone snap rendered through the Love 81 film emulator within the Hipstamatic app.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TALKING ABOUT “TRENDS” IN PHOTOGRAPHY, AS IF THEY SIGNIFY ANYTHING, is like standing near the ocean and commenting on individual waves, as if any one of them will be the standard for all waves forever going forward. More than any other of the graphic arts, picture-making is not so much a strict canon of laws but a seismic measure of our most mercurial moods in a given moment.

As an example, as of this writing (May 2023, in case you wind up reading this in archive), it seems that there has been a recent turn away from the realism of formal photography, once again swinging the pendulum toward apps and software that deliberately muck up precision, processes that celebrate flaws (even artificially created ones), rip pictures free of specific time-era “looks” and otherwise make them sloppier or more random in their result. We are, at the moment, looking for the total effect of an image, including everything that is formally “wrong” about it. Maybe because there is something wrong about it.

The iPhone-bred Hipstamatic alternative to a “serious” picture of the same scene I had taken with my “real” camera.

I am looking at this phenomenon through somewhat fresher eyes these days, even though I have been a long-time user of the ubiquitous and long-running Hipstamatic platform, which has been offering lo-fi tweaks to shooters almost since the dawn of the cell phone era. Problem is, the uneven, customized look of the pictures I created with it have often been categorized in my brain as “something I just do for fun with my phone” versus making “actual” pictures with my “real” cameras. The result was that, over the past ten years, I built up an enormous folder of orphan Hipstamatic images, pictures that I seldom shared and almost never published because I regarded them as cheats, gimmicks, or “just screwing around”….in other words, unworthy of consideration in the same arena as the product of, say, a DSLR.

Which is to say that I have wasted a lot of time trying to arbitrarily disqualify a lot of photos that, upon recent review, really ain’t so bad.

The specific “film” emulator within Hipstamatic that I prefer, a filter effect called Love 81, has emerged over all others as having the proper blend of weathered texture, selective focus, and hyper-saturation that looks both like specific eras or none at all, depending on how it’s applied. And I guess that’s its big strength; the ability to make certain shots come unstuck in time, or to at least suggest times that are unavailable to those of us anchored in the present. Sometimes, like any process, it can ruin what began as a basically okay image, and, also like any process, it can’t make a great picture out of a lousy one. Thing is, our present era is really the best era ever, a world in which photographers can permanently float between disciplines, blithely floating from Never to Always and back to Never at our whim. What could be more human, and more like a photograph?

FEEL LIKE MEXICAN?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I NEVER GOT TO SEE the titanic floating pig that wafted over stadiums for the Pink Floyd Animals tour. And my only in-person glimpse of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade uber-balloons was at street level, the year a horrific wind storm necessitated yanking Underdog and Bullwinkle almost as low as the tops of city busses. Let’s just say that my overall resume on epically inflated beasties is, to be kind, thin.

But, hey, I’ll always have the ginormous Pastel Burro.

That is, at least as long as a local Phoenix restaurant touts its Cinco De Mayo celebrations by mounting this oversized donkey, resplendent in its delightful dumbness, alongside Cactus Road in Paradise Valley.

Hi, burro. Long time admirer, first-time shooter.

Once I finally decided to park roadside and take a crack at it, I figured a dreamy art lens like the Lensbaby Velvet 56 would render it properly. Too weird to be real, too wonderful to be fake.

Maybe I’ll drop in for a quick fish taco.

It pays to advertise.

MAGICAL (PHOTOGRAPHIC) THINKING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

HOLLYWOOD LOVES STILL CAMERAS, exploiting them for dramatic impact in thousands of films over the first one hundred years of the movies. Entire plots hinge on the ability of protagonists, from intrepid reporters to dogged private eyes, to save the day or solve the mystery with a judicious snap, images that spring up in the eleventh-hour of a murder case or point to the tough truths in a medical inquiry. Seems Our Hero (or Heroine) is always on hand with some photographic device that ties the story together and brings it in for a successful landing, ofttimes making his/her camera a key player in the story. Magical thinking regarding photography is a part of the collective movie myth.

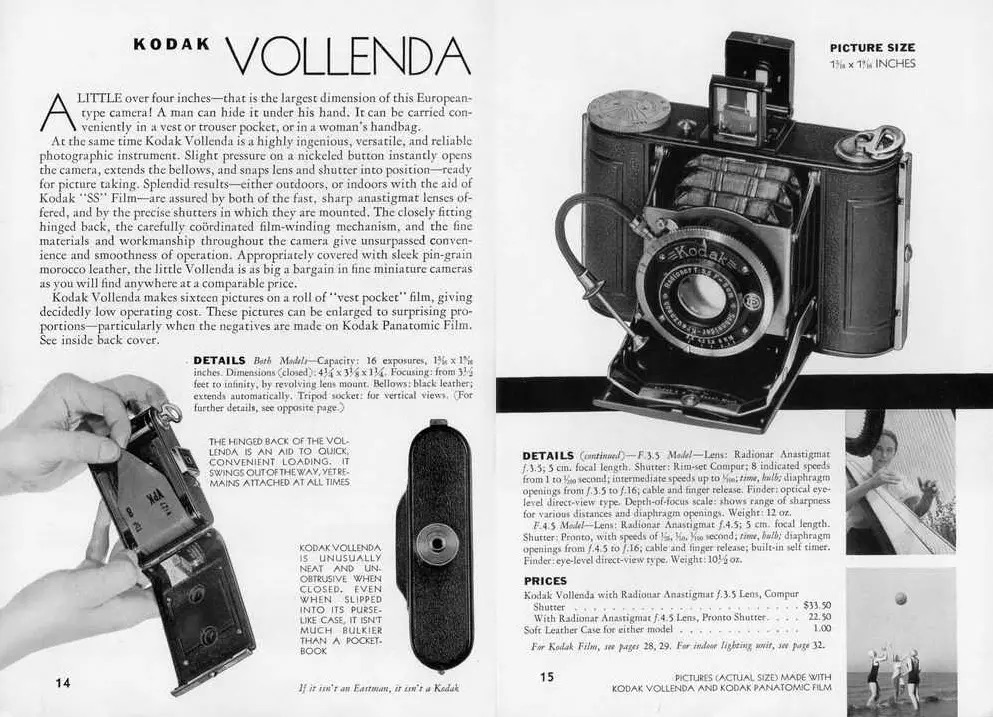

HBO’s recent (and successful) re-boot of the old Perry Mason series is the latest case of a camera becoming a key agent of action in a teleplay, spawning scads of on-line theories about the make, model and performing properties of the sleuth/attorney’s chosen kit. The candidate with the most votes so far looks to be the Kodak Vollenda, a compact folding model (see original ad, above) created by German optical wunderkind and former Zeiss employee August Nagel in 1929 and marketed in the U.S. after he entered into a co-operative deal with Kodak in 1931, the year before the Mason stories are set. The early versions of the camera produced images of roughly 1.25 x 1.62 inches, each taking up half a frame on 127 roll film, giving the shooter better bang for his film buck in terms of picture count but also limiting the size of its negatives, and, in turn, how sharp enlargements (for those climactic courtroom scenes) could be. For your average superstar lawyer shooting a lot of medium and long shots in natural light (or even darkness) with a maximum aperture of f/3/5, this could spell trouble, at least if you were counting on the results for critical evidence. Hooray for Hollywood.

The Vollenda in Perry Mason’s era would probably have fed on the old Verichrome Pan film, with a not-too-aggressive ASA (or ISO) of 125…again, pretty good in brightly lit situations, but not so great when skulking around dark alleys or spying on suspects misbehaving across nightlit streets. But, ah, well, the thing looks amazing in actor Matthew Rhys’ hands, and is historically consistent with the period, despite the fact that its original $33.50 list price would equate to well over $600 in today’s currency, a bit steep for a down-on-his-luck gumshoe in the middle of the Great Depression. But, ah, well, as Billy Shakes often said, the play’s the thing, and Hollywood’s greatest photographic illusion is in selling us all the fantasy of a super camera that save the day by the end of the final fadeout.

Cut.

Print it.

THE FACTUAL / ACTUAL FAULTLINE

Back When The Browns Lived On Main, 2022

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I RECALL A 1972 INTERVIEW WITH A PROMINENT ROCK CRITIC in which he confessed that, three years into the new decade, he was just getting used to the idea that the 1960’s were “going to end”. Not the idea that they were already over. No, he was even wrestling with the concept that they would ever be so. Such is the plastic quality of our sense of time. In some moments, it seems like the things we’re living through will continue forever, while, at other times, it seems like everything, everywhere, is already past. This yo-yo-ing sensation plays hell with our emotions, and, in turn, with the pictures we attempt to create with transient subjects. At least, that’s what happens with mine.

One situation which gets my own internal yo-yo spinning involves making images of small-towns life, which always sets me careening between the sensation that I’m both experiencing something that’s truly eternal and, simultaneously, something that’s as gone as the dodo. Standing on the simple main streets and leafy, sleepy lanes of the villages and burgs that have so far outlasted the twentieth century, it’s easy to be assimilated into the place’s slower rhythms, to briefly be lulled into thinking that it’s really the rest of the world that is imaginary. But then there is the rude shock of walking past a 1940’s drug store, complete with lunch counter and soda fountain, and bumping into a place that repairs iPhones. For a second, nothing makes sense. The two “realities” do, of course, co-exist; however, we are aware that the relics of the earlier era have essentially overstayed their welcome. They are living on borrowed time, the same borrowed time we, as photographers must now use wisely before….before…..

The surreality of shooting in small towns dictates the look of my pictures of them. I tend to use exaggerated tonal ranges, soft, painterly looks and dreamy art lenses on them, rather than merely recording them with the sharpness and balanced exposure of mere documents. As their very actualness is now so fluid in my mind, I prefer to see them as in a dim vision or imperfect remembrance. They seem more poignant for being less fixed in our regular way of seeing.

Like the 70’s reporter that couldn’t imagine his “time” ever coming to a close, I wrestle with the task of depicting worlds that are rapidly receding into the realm of memory. Oddly, making them look less literal bolsters their reality to me. For, like that reporter, I can’t imagine that they are ever going to end, and that dictates how I tell my camera to see. At that point, the machine, the instrument, is as unreliable a narrator as my own memory, just as it’s also made more reliable to my heart.

SOMETHING’S LOST, BUT SOMETHING’S GAINED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AGAINST MY BETTER JUDGEMENT, I OFTEN SUCCUMB to the allure of those endless Facebook memes which pose a mathematical conundrum, i.e., “6 + 10 x 4- 3 – 8 x 3 x 3=? or some such other brain torture. I always labor long and sincerely over the solution, and I am always, always wrong. Instead of spending the rest of my declining years admitting that, sorry, numerical concepts are not my forte, and going my way in peace, I instead keep returning to the scene of the beating and begging for yet another blow.

(This is the part where I attempt to make a tenuous connection to photography. Don’t blink or you’ll miss it..

So here’s my pitch; when it comes to the process of making pictures, I love the endless process of addition and subtraction, the ongoing calculation of where, in an image, information needs to be either included or eliminated. Half my process in composing is spent in determining what size the frame should be, and the other half is deciding what deserves to make the cut within that box. Many other aspects the making of the image, from exposure to the whole color/mono choice, or even subject selection is colored by the initial decision about what will or won’t earn its bit of real estate within a picture.

If the right choices are made, then what I call the Joni Mitchell Balance (i.e., “something’s lost, but something’s gained”) will be struck in such a way as to maximize the impact of the photo. Or not. Sometimes you have to settle for Close, since Totally There is off the menu. Take these two shots as an example. The subject was originally mastered in color (see top), and deliberately under-exposed to quiet the effect of color in comparison with the the three figures on the right. Turns out that even the minimal hues I got were still too distracting, and so I converted to mono (directly above), since I felt that the trio, albeit with a great deal of non-defined detail, were the real stars of the picture. meaning that anything that did more than force the eye in their direction was expendable. I remember hearing the old western classic “Ghost Riders In The Sky” as I snapped the frame, and the idea of figures who destinations or aims would forever be shrouded in mystery appealed to me.

Like those blamed Facebook add/subtract/multiply/divide exercises, the picture required careful calculation and re-calculation. However, photography is much more forgiving than math, and so, at least when making pictures, I will never have to settle for the assertion that there is but one single correct answer to the problem. It’s an admittedly sloppier way to see the universe, but (brace yourself, now) it adds up, at least for me.

NEITHER HEAVEN NOR HORROR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

DEPENDING ON WHO YOU ASK, ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE is either a miraculous boon or an existential threat to mankind, seen by some camps as an opportunity to evolve in untold ways and by others as the fast track to enslavement. As pertains to the arts, a quick scan of current press clippings yields mega-scads of hair-on-fire warnings that all creative pursuits, photography among them, will soon be usurped by Our Machine Overlords. Why, the reasoning goes, should anyone put up with fussy and imperfect human artists when the Frankenstein Brains can be just as creative?

This image, in particular, has recently scared the Bellowing Bejesus out of photogs the world over. As of this writing (April 2023, for you archive hounds), its creator, Boris Eldagsen, has just won the Sony World Photography Awards competition with it. He has also thrown a rock into the pond of public discussion by refusing said prize, explaining that he cannot accept it since the picture was generated by A.I. instead of a camera. Suddenly “someday” has been shoved right into our “present-day” faces, given the image’s compelling realism as well as its nostalgic evocation of an earlier “photographic” processes. If anything can convincingly suggest the look of a photograph, Eldagsen’s entry certainly does. To make it, he typed a series of cues and conditions into a program which produced the results in mere minutes in what Boris refers to as a “promptograph”. “You start from your imagination, and you describe what you would like to have”, he said of the process in a recent interview with NPR, “and you can make such a text prompt quite complicated.” Like many people viewing the results, Eldagsen is both delighted and terrified by the results:

As an artist, I love AI. (But) as a citizen of a democratic country, I’m shocked about the possibilities of disinformation it gives. Anyone that can just type a couple of words can create a photorealistic image of the Pope in Balenciaga. You can’t trust an image anymore. We need some kind of labeling – some kind of fact-checking where you see that an image has gone through certain instances – has been getting proof by photo editors. Only then we can know it’s an authentic picture – shows something that has happened.

What’s been missing from all the panicky reaction seems to be the plain fact that photography has always, always lived at the juncture of pure light recording, technological manipulation, and the artist’s vision. Photographs are a group effort, never devoid of whatever tweaking and “post” is out there at the moment or the raw act of freezing time but always in the service of an artist who decides what the mix should eventually be. Every change in recording medium, technical gear, enhancement or format has been initially met with, at best, disdain, and, at worst, outright outrage. But just as photography never supplanted painting, A.I. imaging merely needs to be labeled and marketed for what it is, neither heaven nor horror, but merely another way to tell a story. If you love the mechanics and science of a camera-rendered image, stay in that lane. If you want to see what else is out there, trust the story you’re telling more than the language you choose to tell it. Given the advance of photography over its first two centuries, “Promptographs” have no clear advantage over conventional picture making; both require a thinking mind as their initial spark.

WITHIN THE WITHIN

Wide lenses can capture a lot of data. Sometimes too much.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A FULL YEAR AFTER SWITCHING FROM CROP SENSORS TO FULL-FRAME SENSORS, I am still getting my bearings on some elements of composition, at least as I had grown used to them. To greatly over-simplify, the focal length of my lenses has, for more than ten years, been magnified by about 1.5x, so that, for example, a 35mm lens would “read” on a crop sensor as a 50mm. That determined what I’d would or wouldn’t see in the frame, with the biggest cramping occurring in wide-angle shots, where I live about half of the time.

The result was that my mid-70’s 24mm, a real- go-to for me, was actually delivering the aspect of a 35mm; still wide, but not really panoramic. This was no big deal, since I got used to composing and cropping for what my camera was seeing and shot accordingly, as we all do. The real difference is being felt now, when my 28mm on a full-frame is really 28mm, meaning that a whole lot more…..stuff is being included in my wide shots than before, stuff that I must police much more stringently than I might have done in the past.

Take a look at the shot up top, taken inside a stable, empty except for a single horse. There is so much space within the frame, all chock-full of equipment, gravel (so much gravel) and other atmospheric elements that the purpose of the shot, right out of the camera, can easily be interpreted to be, aww…the poor horse is all alone in this huge building, as if that’s the “message” of the picture. Now, from my vantage point, I could not have framed any tighter; my location was dictated by barriers that held me back at quite a distance. And, since I’m shooting with a prime lens, I can’t zoom, so all compositional control defaults to how I will crop later.

The horse, not where he lives, is the real story.

Turns out that it takes very little extra space around the horse to sell the idea that he’s “all alone”, so I can easily cut stalls, hay bales, and other filler off on both sides and still easily convey his “solitude”. But here’s the deal; once I started cropping, I began to observe a different story emerging in the picture, since now I was actually seeing the small arm that’s coming in from the right to pet the horse. Now the image is about He’s Not Alone, that, in fact, someone cares about him enough to stop and offer a bit of tenderness.

Wide-angle shots can sometimes keep us from getting into our pictures, and, if we change the way that we see what we shoot, such as the revision of “what is a frame” that I’ve been dealing with recently, our viewpoint can be modified in subtle ways. Shooting wide is a great tool, but only if we reserve the option, upon further thought, to think narrow as well.

THE KEEPER OF THE LIST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN ALL THE YEARS I HAVE WATCHED HER PRESIDE over hundreds of both seasoned and starter birdwatchers in the Arizona desert, I can’t recall ever having seen Andree Tardy without her signature We Are Serious About This Stuff sunhat and her loose khaki fatigues. Chances are that if I were ever to bump into her in “civvies” at the local Safeway, I might easily pass her without notice, even though, by now, she has served for years as our group’s go-to Earth Mother, an empirical and encyclopedic source of information on Which Birds Breed With Who, how their plumage changes with the seasons, why the immatures are less resplendent than the adults, and how you can distinguish a “Too-Whit-To-Whoo” from a “Wit-Wit-Wit-Too-Too”. Because she is just that good.

“Okay, did anyone see any vermillion flycatchers?”

I mention Andree’s all-season costume because, for us, it is inextricable from her physical form, the “plumage” by which we identify her “behaviors”. Tough as a turtle’s toenail and consumed with a passion that defies the damage of time, she is, at 81, hardier than many of the sex-and-septuagenarians that trail behind her like lost chicks. That bottomless supply of energy is fed by an insatiable hunger to know more, to see what’s around yet another corner, and the corner after that. I have shot dozens of candids of her over the past twenty years, but I find that minimal images of her in full birders’ regalia registers even higher than a mere facial portrait. She just is the sumtotal of all her outer contours. from her fingerless gloves (easier to work binoculars with) to the billowy slacks that protect her from the scars and scrapes of desert plants to the headgear that all but obscures the aquiline angularity of her face. I can’t imagine making a picture of just her face. It would somehow seem incomplete, like Schweitzer without a pith helmet or Superman without the cape.

The other object that is constantly with her is only withdrawn at the end of bird walks, but is as crucial as every other component in her makeup: The List. Andree’s lifetime role as teacher, interpreter, guide and dauntless ornithological doyenne demands that, at the end of the day’s spotting, she, and she alone call out the categories and species, the better to officially tally the count of what, to a certainly, was actually seen. She knows she can count on us all to honorably report our individual sightings; after all, birding, unlike fishing or hunting, is a system built on honor, along with a proper Hippocratic pimch of “do no harm”. Anyone can teach someone else about birds, but The Lady Herself also teaches respect, humility, responsibility. The birds, and all who choose to watch them alongside her, could not be in better hands.

THE DEVIL’S IN…

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

A GAME OF INCHES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TO BEGIN WITH, EVER SINCE THE INSTANT I TOOK THIS PICTURE, I have wondered if I had the right to.

The all-invading eye of the camera should be tempered at times by our awareness that it allows us to look in places that perhaps should remain beyond our discovery….that, having seen a thing via these miraculous machines, we cannot ever un-see them. This feeling has accompanied the most recent images I’ve made of my parents, both now in their nineties, both unsteadily Pulling Into The Station, so to speak. Their every day is a high-wire act that vibrates between desire and risk, between the drive to do what they once did so effortlessly and the daunting dilemma posed by trying to do, well, anything. They are playing a reverse game of inches.

I want to stop what time is still left. I want to lean on the camera’s reliable value as a recorder. I want just. one. more. memory. And yet, in chronicling the ever-tougher track of their days, I am aware that no single frame will convey what I’m seeing, or can ever sum up a near century of living, striving, failing, loving, dreaming. And so I keep making pictures, pictures that will always come up short, even as they are increasingly precious.

I can often feel as if I’m violating a trust, making these images.

The one you see here is of a very ordinary thing; my father, at ninety-three, doing his weekly physical therapy session. He needs it to shore up his strength, protect his muscles against atrophy, improve his balance. Beyond that, he needs for his body to have something achievable to reach for, just as his still-acute mind is still stretching to embrace ever-new concepts and projects. His focus in these sessions is determined, but not angry; he knows how much has been taken from him and my mother, but his emphasis is not on regret, but instead on squeezing the juice of opportunity out of every instant of time he has left to him. Me, I have to force myself to photograph this all as dispassionately as I can, since it’s me, not him, that is mad, that indulges in self-pity. But that’s my parents; gaping into the chasm, they are still turning back toward me, the everlasting upstart student, as if to say, watch carefully; this is how it’s done.

This morning, driving around my neighborhood and mentally sketching a layout for this post, I asked Siri to play a song that, for me, has gained additional poignancy over my lifetime, Carly Simon’s “Anticipation”, knowing full well that I would be sobbing by the end of it. Still, in the context of where I and my parents are at the moment, I also knew it would leave me feeling, in some amazing way, grateful for its wisdom:

And tomorrow we might not be togetherI’m no prophet and I don’t know nature’s waysSo I’ll try and see into your eyes right nowAnd stay right here ’cause these are the good old days

THE RIGHT-HAND BRACKET

By MICHAEL PERKINS

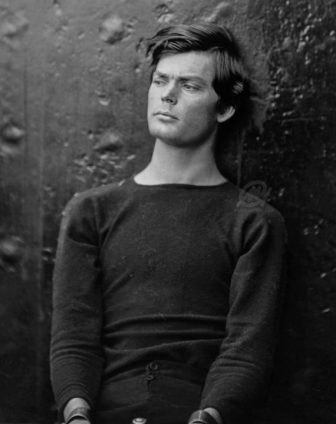

SOME OF THE MOST HISTORICALLY ESSENTIAL IMAGES from photography’s first decades were created without much public awareness of their authors, as many of the art’s earliest practictioners labored unsung and uncelebrated. In painting, drawing, poetry or literature, tracing the creators of the great works of the 1800’s has proven far easier than crediting those who made the first world’s first immortal photographs. The feeling that the world could, should be documented far preceded the notion that individual voices in that historical work should receive their due.

In some ways, the American Civil War served as the launchpad for the first photographers to be personally recognized and marketed as a “brand”. At the beginning of the conflict, only Matthew Brady, who operated the first true professional studio out of New York, was anything like a household name to the general public, with the illuminati of the Victorian age beating a path to his door for their moment of immortality. Once war broke out, Brady exported his fame by dispatching several wagons of mobile darkrooms across the country, documenting the North/South carnage in a way that had never before been attempted anywhere on earth.

It was inevitable that at least a few members of the army whose war images were universally credited as “photo by Brady” would aspire to emerge from their anonymity, and one of the first such to succeed in going solo was Alexander Gardner, a Scottish immigrant who, like Brady, had initially distinguished himself chiefly as a portraitist. In one of history’s great in-your-lap twists, Gardner landed one of the grimmest photographic assignments of the 19th Century when, at the war’s end, he was chosen to create portraits of the conspirators who had aided John Wilkes Booth in murdering Abraham Lincoln.

Visiting the prisoners (including Lewis Powell, above) in their cells, Gardner snapped images that can strike the modern viewer as remarkably informal and candid, even contemporary in their aspect. And then, within days, he suddenly reverted back to his wartime role as a pure chronicler, assigned to document the plotters’ executions. His before-and-after series of the hangings, gruesome as they were, were also, for a grieving nation bent on revenge, in high demand, marketed on post cards, magazine covers, photo-derived lithographs and even glass slides for magic lantern projectors. Matthew Brady may well have provided the left-hand bookend for a national tragedy, but Alexander Gardner provided the right-hand one. And in between those brackets, the art of photography was changed forever.

OUT OF HIS SLEEVE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE TRUEST TEST OF ANY GREAT ART is endurance over time. We’re not talking the mere ability of the work to survive physically, through preservation or curation; just managing to not crumble into dust is not a major accomplishment. No, the real proof lies in the time-travel property of art’s intention or vision, the ease with which it leap-frogs eras to give new audiences a glimpse of what sparked its original creation. Things last because they continue to relate.

In my personal case, one of the joys of photography has been in trying to use my own limited powers of interpretation to view lasting works of art and try to see something fresh in even the most famous among them. One of my chief targets in this joyrney is the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, designs that continue to turn a fresh face to each succeeding generation and thus invite re-evaluation.

This is especially true of Wright’s lesser-known projects, some created in his ’90’s, when he told Mike Wallace that, however many more years he might live, he could just “keep shaking them out of my shirtsleeve.” Indeed, at his death in 1959, dozens of his designs remained unbuilt, such as this side court on a church whose blueprints were purchased from the Wright Foundation by a Phoenix congregation decades after his passing. Unlike his superstar signature pieces, this quiet structure has not been photographed to death, allowing both viewer and shooter a fairly blank slate on which to inscribe whatever impressions they choose.

Art bounds across time to delight us anew because we find our own age’s reasons for loving it. Photography is a vital tool in this quest to see established works from a new angle, in a new light, offering fresh messages.

THE WOMAN WITH THE WALKING STICK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF “LIFE” IS DEFINED AS THE STUFF THAT HAPPENS while you’re making plans, Photography can be said to be comprised of the pictures that emerge while you’re planning other pictures. We have all begun setting up what we hope will be the ideal frame when something from just offstage screams, “hey, look over here.” Success and failure, then, are often measured by how insistent them strange little voices can be.

In the astringent desert vistas of Arizona’s Tonto National Forest, merely the shock of color generated by a late-winter “superbloom” of Mexican poppies would normally be all the visual fuel needed for a luscious landscape. And, just ahead of this shot, things certainly started out that way.

And then I saw Her.

Just a solo woman with a walking stick. Just one small figure with a determined stride, separating from the roadside throngs of thrilled snappers wading through the golden waves of flowers and striking out on her own to head….where? Her actual destination was unimportant; more importantly, her very position in my viewfinder had given an “okay” scene a stronger central axis.

Walking along a wire fence, she reinforced its receding line, pulling the viewer’s eye into the picture and toward her. Her separation from the parallel highway and the distant mountains established scale. And finally, showing a scattered field of poppies provided more contrast and texture than the unbroken blankets of them available just across the road.

Start with one plan, shift gently to a slightly different one. Think them both through and make a deliberate choice. In an art that strives to be less about taking pictures and more about making them, challenging your first instincts is a habit worth cultivating.

TEST (OR MOEBIUS) STRIP

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

SOME IMAGES ARE THE FINAL DESTINATION for a concept, while others are only the launch pad for one. For most of its first century, photography was, at least for non-professionals, a sort of “straight out of the camera” proposition. You calculated, aimed and clicked, and what you got was, for all intents and purposes, your final product. Sweetening and manipulation was for the elite.

Now, tech has conferred the gift of boundless tweakery on everyone, meaning that a photo is not “done” unless we are completely through fiddling with it. Artistically speaking, this removes all barriers to, or alibis for, unsatisfactory results. It’s both empowering and intimidating, as it means that photogs, and not cruel fate, are ultimately responsible for the final version of a picture.

Witness the steps in the gestation of a photo that many of us already see as a somewhat average process:

The image seen here began life as a phone snap of the ceiling understructure inside a mall that had been stripped to the bones ahead of a restoration. After the initial snap, I cropped out the lower retail storefronts, leaving me with a mere patterns of girders and supports. I then coverted it to mono, ran it through an app that created a mirror image of one half of the pattern, and finally used a “mini-planet” platform that transformed it into a spiral. And I still may not be finished.

The sheer giddy joy of having this amount of freedom is far more important than what I myself choose to do with it. The main takeaway is that, for all photographers everywhere, the training wheels are truly off the bike. It’s an amazing time.

SECOND SIGHT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ME, ONE PREDICTABLE TAKEAWAY FROM THE RECENT PLAGUE YEARS has been a forced re-ordering of my priorities and pleasures as a photographer. Quite simply, the conditions imposed by a need for caution and patience have not only made me see differently, they have altered what it is that I look for in the first place. Any time you change the number of places you can go, or reduce the total number of things you can get near enough to photograph, your pictures will automatically be re-shaped.

In my own case, the isolation imposed by The Great Hibernation moved me about three feet forward as a bird watcher.

My wife and I had already been settling into the division of labor seen in many birding couples, in which one partner spots ’em and the other shoots ’em. This is totally logical since I am not even ready for the Rank Amateur Semi-finals when it comes to identification, and makes even more sense since Marian would rather experience the birds in the moment, through binoculars, than worry about “capturing” them. The result is that I learn how to slow down and learn something before I shoot, and she gets the souvenirs at the end of the day. Happiness all around.

A checked box on my wife’s birding “life list”; a flock of Cedar Waxwings convenes in Tempe, Arizona, 2023

This year afforded us an exercise in patience that, frankly, I might have muffed just a while ago, in that we spent weeks searching for the same avian pot of gold, with lots of frustration and near misses along the way. Colder, wetter winter weather in the higher altitudes of Arizona had created a shortfall of food for several species, forcing them down into the massive deep bowl in which the Phoenix metro sits. This in turn created a surge of one of Marian’s “life list” birds, those special rare sightings that birders truly live for. That bird, the cedar waxwing, was suddenly popping up in massive flocks everywhere, usually in the company of a throng of robins, who are no great shakes in many parts of the country, but are fairly rare around here. The affinity of the two species for each other meant that if you saw a single one of either bird, chances are you were near a major gathering of both. The hunt was on.

I relate this tale to reaffirm that, in The Before Times, I was just peripherally aware of birds, in that they were something I occasionally photographed but seldom had as my primary focus. The intervening years have changed all that, something I realized when, at the point we happened upon a motherlode of waxwings and robins surging into a local pocket park, I not only felt I had accomplished something photographically, but also that I had experienced real, unalloyed joy. My wife and her friends had finally had me in their classroom long enough to get my attention. And while I will probably never have the discipline to become a great wildlife photographer, at least I know, now, what I could be missing. And that’s a gift beyond measure.