AS ADVERTISED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CALIFORNIA HAS ALWAYS BEEN ITS OWN BEST PUBLICITY AGENT, burnishing its already dazzling visual beauty with idealized vistas in posters, packaging and legends that elevate the state from a mere paradise to something like a fairyland. Anchored in my midwest reveries in Columbus, Ohio, my own first glimpses of scenes of the far west were not candid photographs or documentaries, but the golden bounty of the land as depicted on fruit crate art. Long before I experienced the range of light that is a daily miracle in its mountain skies and coastal beaches, I saw it simulated like some fantasy landscape in Maxfield Parrish’s over-the-top posters for Edison Mazda Lamps. And decades before I would step off a plane to experience the Golden Gate first-hand, I marveled at postcard-perfect views of San Francisco through the lenses of a View-Master.

Now, long past all those childhood visions of California, I actually live here, and am amazed to see the same sort of light and color that I had assumed were mere hype and boast, only to find the very vistas that inspired so many brochures, magazine spreads and travel guides. The amazing thing is that the real deal is not that much removed from the imaginary when it comes this place. The shot you see here, of part of the old Santa Barbara State University campus, is pretty much straight out of the camera, although I retreived some details from the more extreme shadows. And this picture, I find, is not an anomaly, but the daily legacy of life out here.

The only thorn on this rose is what the California native knows about his Eden…that protecting it from the ravages of the very people who claim to love it can break your heart, overwhelm you with the task you are charged with, to save, serve, defend, replenish. Photography is the religious worship of light and what it can beautify. But in all that beauty is buried a challenge; we must remember that we are not owners but merely caretakers, and that we must use the arts for, among other things, reminding everyone just what is at stake. Only in that way can the wonders we cherish most about this world continue to delight as advertised.

NEW ANGELS

Current, a rope and cord art installation in Columbus, Ohio, created by “fiber artist” Janet Echelman

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ME, ONE OF THE MOST EXCITING TRENDS IN URBAN DESIGN, in the twenty-first century, is not the latest generation of skyscrapers or town plazas, but a bold new redefinition of the concept of public art. Where once it was sufficient to plop down a statute of some wartime general near the county courthouse, commissioned works now make mere sculpture look as primitive as cave paintings. We have evolved past the commemorative earthbound seraphim that once graced our parks, to flights of fancy that connect and shimmer from the air. It is an age of New Angels, and Janet Echelman is one of its patron saints.

Echelman, a Guggenheim fellow and Harvard graduate, who refers to herself as a “fiber artist”, is, in fact, an altogether new kind of sculptor. Instead of being grounded on pedestals, her arrangements of shimmering color, created by mixtures of fiber, netting and rope, hang in suspension over cityscapes like vast spider webs, refracting the rainbow and generating waves of shifting hues depending on changes in sunlight, wind or the angle of view. Some of her creations are billowing circles and cones that resemble a whirlwind of cyclone; others look like sky-bound rivers, curling and twisting into tributaries of red and blue. Each is uniquely tailored to its specific location in cities like San Francisco, Vancouver, Seattle, and a half-dozen other cities around the world. They are, simply, magnificent, and the best challenge for any photographer, since they appear vastly different under varying conditions.

I first saw one of her works while working at Arizona State University, where Her Secret Is Patience floats like a phantom hot air balloon near the school’s Cronkite School of Journalism. And just this spring, I was thrilled to see her first work to be floated over an entire intersection, 2023’s Current, which spreads across the meeting of High and Gay Streets in Columbus, Ohio, anchored to the tops of buildings at the crossing’s four corners. Commissioned by a local real estate developer as a kind of front porch for his refurbished bank building (now housing deluxe condos), Current can be seen from any approach within a four-block distance of the area, an irresistible advertisement for the regentrification of the neighborhood. Janet Echelman is but one voice in a rising chorus that demands that public art re-define itself for a new age. That age will not only withstand controversy but actively court it, just as any art, including photography, needs to do.

THE STRAIGHT (AND TALL) SKINNY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY TIME OVER THE PAST TWENTY-FIVE YEARS that I have strayed from my home in the American southwest and headed back to my mid-Ohio roots for family visits, I am struck by a stark difference in the general arrangement of architectural space between the two regions, or at least a difference that I myself perceive. It would be a monstrous over-generalization to say that legacy houses, out west, tend to be horizontal in orientation while midwestern houses in older towns tend toward the vertical. I have absolutely no empirical data to back up this impression, only the way that it strikes my photographer’s eye.

Western dwellings strike me as variants on the basic ranch house design, with many homes arranged from left to right, many without basements or attics. Midwestern homes, by contrast, seem to be narrow and high, resembling a brick turned up on end. I tend not to actively notice this distinction unless I am back home, trying to compose frames in which several buildings cluster together to suggest an entire town or street. My hometown of Columbus, Ohio, which is a sprawling city composed of many legacy neighborhoods, boasts a ton of “tall-and-skinny” sectors from the Short North to German Village to outlying villages like Pickerington or Reynoldsburg. In many of these neighborhoods in which, unlike say a city like Brooklyn, houses need not be crunched and crowded together like a row of brownstones, the brick shape still often predominates, setting up a strange contrast between wide, deep yards and narrow, stretched headstones of design.

Sometimes the look of a small town can actually seem like the view between gravestones. And, in the rural areas where the local cemetery is actually cheek-by-jowl to to the residential districts, the connection is even more compelling. I walk these Midwestern streets, once as inevitable as breath to me, and realize that not only my physical address, but I, myself, have undergone deep, deep change. And that, in turns changes the pictures I envision.

DOWN TO THE BONES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TOWNS, VERY MUCH LIKE THE PEOPLE WHO CREATE THEM, don’t pass away all at once. Over the lives of neighborhoods and villages, as in the lives of the people who populate them, there are various ebbings and flowings of health. Even years after there are no more comebacks or rebirths, decline itself takes on a slow, predictable rhythm. Streets and businesses can, indeed, take a long time to die.

America is a place where beginnings are over-ripe with hope, as if nothing that happens after the word “go” is even worthwhile mentioning. In such a place, nothing says, “this no longer matters” like the empty, featureless faces of ebbing storefronts. Once performing as mission statements for their proprietors (“now open!” “lowest prices in town!” “bargain city!”), these places start to resemble an old actress who no longer care to put on makeup of brush her hair. The buildings remain standing but their faces are blank.

Towns like this one (let’s protect its privacy) are so stripped of ornament that they become mere jumbles of rectangles, building-block puzzles with few messages outside, no hope inside. Still, as abstract versions of their old selves, they can make interesting compositions, even as their continuing existence is both mysterious and sad. We love the start of things. We avert our gaze rather than acknowledge the end of them.

I WAS A TEENAGE CAMERA-SMASHER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

JOE McNALLY, WHOSE ASTOUNDING IMAGES HAVE GRACED THE PAGES of Life and National Geographic, along with far too many other to be mentioned here, has, in recent decades, developed quite a roadshow as an ambassador for Nikon products. What began as a few simple tips and tricks eventually blossomed into a grand presentation of his greatest hits and a hilarious TedTalk-type chat about the many mishaps and near-death experiences he as accumulated in Getting The Shot. His results “in spite” were always astonishing, but the takeaway for me was knowing that there was at least one other super-talented shooter out there who was also something of a doofus. I needed, really needed to know that everyone gets their share of gasp-inducing smash-ups.

I have littered the cloudscape of Camera Heaven over my lifetime with all the devices I have dented, dashed, dropped and dinged. These include my Kodak Instamatic M12 movie camera, which I lost hold of only to watch its battery gate smashed to bits (I finished the film roll by rubber-banding it back on), a Polaroid Colorpack II which disintegrated in my hands during a wintry shoot, and two recent face-plantings followed by bad bounces for both my Nikon P900 and Z5 (both survived, to varying degrees). In most cases, the so-called “ruined” cameras continued to function after the mishaps, leaving mostly my pride or dignity as casualties. Some of my favorite shots of downtown Los Angeles, for example, were taken just minutes after the shutter on my camera froze from old-age, allowing me to nurse it through a few more crucial frames before it finally seized up for good. One such image, of the majestic Eastern Columbia building, is seen here.

Cameras live and then cameras die and we grieve and we move on. Seeing something physically damage your favorite tool is a great way to be reminded that it is merely a tool, that you take the picture to a much greater degree than any bit of gear you use to help you do it. But I still love to hear the Joe McNallys of the world admit, in front of witnesses, that they have almost dropped a flash bulb from the top of the Empire State Building or have watched multi-thousand-dollar equipment cases bubble beneath the surface of a bog in Eastern God-Knows-Where. Weirdly, it helps Little Me soldier on.

THE MOMENT IT CLICKS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER MARRIED TO A BIRDWATCHER, I WAS PRETTY MUCH DESTINED to eventually cross over into her world, especially given the natural affinity which has always existed between the two hobbies. Like the making of pictures, the science of spotting and organizing data on the world’s winged wonders is based on the thrill of discovery, a unique mix of surprise and wonder.

Eureka moments.

The sound made by a birder who’s just checked a pileated woodpecker off his “life list” is similar to the cry of joy/relief a photog makes when the plan for the image comes real. And when both kinds of people occupy the same space, it’s inevitable that the photographer will be tempted to try to capture, not merely the birds on hand, but those who get emotionally supercharged when they spot a beauty.

I have captured many manifestations of pure joy among birders over the years, since, due to my inability to see even half of what the experts see, I have lots of time to troll about looking at everything else, including the local scenery and the gleeful faces of those whose knowledge occasionally affords them a major payoff. The frame seen here encapsulates that feeling, the moment when Nature grants you The Big Reveal.

A Eureka moment.

Birding is also like photography in that there is a definite learning curve, an apprenticeship which encourages humility. Being good at anything means slowing down and waiting on the process of learning. It is never immediate, and there are no real shortcuts. Either you put in the time or you fail.

But, God, the joy if you hang in….

GOING-AWAY PRESENTS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

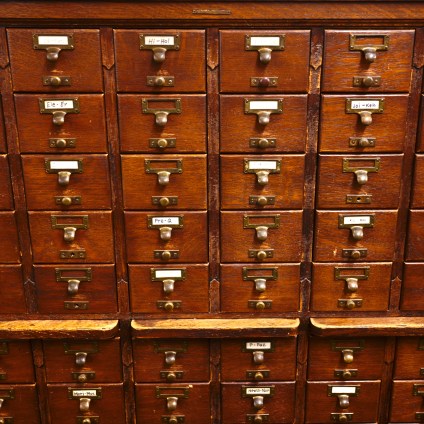

YOU MAY REMEMBER THE BRIEF 70’s-ERA FLING MANY OF US HAD with the wooden cases that were originally designed to carry the metal type used in composing newspapers and magazines. We stored them vertically on walls and stuck cute little knickknacks in the compartments, re-purposing something that once had been so universal as to be invisible to most of us into something we paid fresh attention to, now that it was charmingly obsolete.

Photography, being at least part reportage, is uniquely equipped to take note when everyday items become rare curiosities. You can take measure of this process poring through the tons of articles listing the common objects from earlier generations that later generations can no longer identify, like Rolodexes or rotary phones. Antique stores, which are mostly resale forums for other people’s old junk, are replete with things that were once essential and are now peripheral. Sometimes, the shocking distance between eras can produce good grist for images.

When the everyday becomes the vanished, like this old library card catalog, we are removed enough from them to note individual elements of them, like materials, design, patterns….all the practical aspects that their inventors had to balance to make the things. You realize that there were once several support industries just for these catalogs. Someone had to make the file cards. Cabinet makers were engaged; there were special varnishes to seal the wood, metal rods to anchor the cards in place, brassworks to make the pull handles. There were people who could sit you down and spend an evening just discussing the finer points of this catalog company versus another. Expertise was gained. Factories were engaged; people hired.

Can a photograph of an obsolete library tool evoke any or all of this? Depends. There are no guarantees that either a snapshot or a deliberately composed picture can or will do the job. But, at the very least, our understanding of earlier versions of ourselves begins with a physical document of what those people lived with, and around. And that narrative is always a potential treasure.

THE GIRLS WITH THE ELECTRIC SMILES

THE GIRLS WITH THE ELECTRIC SMILES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS AS LEGACY CONSTITUTE REAL WEALTH for us as we age. Heirlooms like jewels, or books, clothing, all contain powerful energy when viewed against the backdrop of the memories of those who have gone before us. However, the accumulated madras quilt of physical images is that backdrop, the most perfect proof we have that these people lived, and loved, and yearned, and strove. That kind of inheritance is truly beyond price, and, in my family, photographs are incredible talismans. They call spirits forth, anew.

My parents were both avid snapshooters as my sister and I were raised. Slides, prints, home movies, framed histories lined all our walls, crammed every cranny atop pianos and nooks and shelves. The visual documentation of our lives not only acted as parameters for our everyday lives as kids, it is now a miraculous comfort for our own old age.

Mother, mid-1940’s.

But photographs have done more for me than just parade my own past experiences before me. They have also granted me entry into the time before my own, to see my parents as children, teenagers, young lovers. To see the bright boys with the cocky attitudes and the gorgeous girls with the electric smiles. Before all the wars, trials, sorrows and slams of grown-up life. Before the world tried to tame them, force them into line, steal their joy. Before they even dreamed of being Mom and Dad.

As it happens, I am writing this on Mother’s Day 2025, but, in practice, these frozen pieces of personal history are truly a part of my daily life. I need all those fresh-faced grins, the unguarded moments caught in a box, the markings of days major and minor in the lives of the people who shaped me. They created, or curated, these photographs for an inheritance they could never have foreseen. But intentional or accidental, they are my legacy, and I cannot imagine life without them.

WALK BETWEEN THE RAINDROPS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE PICTURES, AND THEN THERE ARE PICTURES OF PICTURES, and then…

At this point in the history of photography, we have probably made almost as many images of other people’s images as we have made original photographs of our own. We cop a shot of a great painting; we snap a souvenir of a stunning statue; and then, there are those other kinds of “pictures of pictures”; those that are actually also of the surrounding spaces around and between them, as seen in galleries or museums. And while it may seem odd to think of light fixtures, benches, or visitors as part of the same composition as an art exhibit enshrined in those spaces, I find it an exciting challenge to take in entire rooms….paintings, furnishings and all, as a single piece, almost like a stage set.

Well, let’s face it; galleries are stages, and their look is set or designed so that every element in it enhances all the others. This means organizing both active and empty space as a continuum, and it means thinking dynamically about the role of those spaces where “nothing” seems to be happening. Open areas give the works room to breathe; the eye can then, in the words of Steely Dan, “walk between the raindrops”.

In the above shot of an art gallery in Santa Paula, California, what was once just one of many tall, arched windows in an old bank building becomes, under the careful curatorial eye, a centerpiece of the frame, affording a view of the outside world which both reflects and amplifies the beauty of the framed art. Everything works together, and yet nothing collides or occludes. Visually, there is space for all of it to happen, on equal terms with itself.

Is that zen? Is it feng shui? Is it just the fever dream of your humble author? Who knows and who cares? The paintings, designed to be seen on their own terms, can also be viewed within a context that caresses them, completes them in a way. And I’ll make a photograph of that any day of the week.

A GRAIN OF TRUTH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TEXTURE IS ONE OF THE MOST VARIABLE FACTORS in photography, in that its importance in an image goes all over the map given the situation. While exposure and composition, even focus, are key considerations in the making of nearly every picture, texture can jump to the front of the line and become the crucial element in the making of a photograph, moving from merely part of the story to its central point.

In photographing, for example, Da Vinci’s Last Supper, you’re creating a narrative not only on the figures in the fresco or of the painter’s technique; you’re also making a document of the current physical condition of the work, commenting, in effect, on its state of deterioration, the befores and afters of any restoration efforts, even the grain and grit of the surface itself, since, over the centuries, the art, and what it was created on, are now inextricably linked; two halves of a whole.

Murals in particular can only be complete documents when the aging or weathering factors on surfaces can become part of the story. This memorial to the central west coast’s oil industry (top) seen on the side of a building in Santa Paula, California, can, years after it was created, no longer merely be a painting or an homage.

In a very real way, the wall has become part of the painting, an expression of the toll of years since the town’s glory days. This elevates texture to the status of a key factor in the relating of the area’s history. As seen in the detail, just above, the peeling and cracking of the work is a story in itself, an unstated what happened? that forms in the mind of the visitor. as in the Last Supper or other venerable works, the ravages of time root an event or an era in fixed historical position. We are aware that we are looking at a relic, still visible in this world; a souvenir of other, vanished worlds.

In photographs, the final effect ranges from casual to formal, from mere reportage to historical commentary. We bring intent to a scene when we capture it in a box, adding accents along the way to underscore what we feel about it. Come to think on it, that is about as close to a working definition of texture as you can get.

FADE TO BLACK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WAS NOT YET DEEPLY INVOLVED IN PHOTOGRAPHY in 1968, the first time I heard Jimmy Webb’s song Watermark, which he wrote when he was collaborating with the actor Richard Harris, who, owing to his role as King Arthur in Camelot, was briefly celebrated as an intriguing, if unconventional, singer. The lyrics of the song try to capture the essence of things that are not destined to be preserved, to rail against the fading and impermanence of memory. A half century had to pass before a song that I really enjoyed at first hearing became the very definition of the magic trick we attempt in making a photograph.

But enough talking. First, an image:

And now, the words that make all such images so, as Webb writes “draped with my regret…”

How delicate the tracery of her fine lines

Like the moonlight lacetops of the evening pines

Like a song half heard through a closed door

Like an old book when you cannot read the writing anymore

How innocent her visage as my child lover lies

Pressed against the rainswept windy windows of my eyes

Like an antique etching glass design that somehow turned out wrong

I keep looking through old varnish

At my late lover’s body

Caught on ancient canvas

Decaying, disappearing

Even as I sing this song

How tenderly the tapestry is draped with my regret

And the bittersweet inbroidery that hasn’t faded yet

But I see the details dying in that distant soft design

Like the taste of summer fading like from a dusty winter wine

How secretly and silently my sorrow disappears

You can’t see it with your eyes or hear it with your ears

It’s like a watermark that’s never there and never really gone

I keep looking through old varnish

At my late lover’s body

Caught on ancient canvas

Decaying, disappearing

Even as I sing this song

OUT OF ONE, MANY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOME PHOTOGRAPHIC SUBJECTS ARE SO DENSE that they simply give the eye too much to decode or prioritize. When in the act of shooting immense or complicated compositions, I often fail to see that I am taking in enough information for two or more completely different images, and that wielding the scissors this way or that can drastically re-direct the intention of the picture. This is perhaps why shooting vast landscapes only works occasionally for me as wholes. I see the mountains and the neighboring farmlands and the barns and the babbling brook and am never certain if, in a single frame, I’m actually creating more confusion than clarity.

One recent example of my not being aware of this, at least not in the moment, happened last year as I stepped inside St. Patrick’s cathedral in midtown Manhattan. This massive space was devised in a time when going to church was a sensory experience that was designed to be overwhelming, to inspire awe, where even the cheap seats afforded complex, competing vistas. In taking a rapid series of snaps, however, I came away with a feeling of sensory overload, with many images containing more than enough information to be cropped by half, or even two thirds.

The original frame, seen up top, sends my eye looking into so many sub-stories at once that a general view is, well, too much of a good thing. A left-handed crop (middle image) make the picture about something, as attention is now centered on the beautifully ornate pulpit. Cropping to the right, we see a story that could be about worshippers on a journey; that is, heading from front to back in search of something, perhaps the devotional altar in the distance. All cropping is, of course, a creative act all its own, with its own dictates and designs, and sometimes a very busy image can be stunning (think a complex overhead skylight of concentric stained glass panels). However, many of the big canvasses we shoot could be, if you will, subdivided into even more effective individual parts rather than one stunning whole. Reviewing our old so-called “very good” pictures can often find a “wow” picture hiding within.

IT’S RIGHT ON THE WAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WON’T SAY THAT I’M EXACTLY GRATEFUL for my meager skills as a birdwatcher, but I will state that, in my specific case, being mediocre at it has been a boon to my photography. To be more precise, my inability to spot as many varieties of winged wonders as my birding companions often results in my mind wandering while others about me are transfixed, as the photographer in me swiftly moving from “what birds are to shoot?” to “what else is there to shoot?”

Fact is, when the rest of the pack is following the various melodic “whoots” and wheets” of whatever is hiding in the foliage, I frequently answer with the call of the adult Dull-Witted Geezer, a song that sounds like “WHERE? WHERE?” as I rotate my head madly from side to side. Here’s the deal: when I can’t see what everyone else can see, my attention flags, at which time I’m glad that most of the outings are half birdwatch and half nature walk. Because, let’s face it, many birders come home from a walk with bupkis to show for their efforts, while a nice little saunter through the woods always yields something. And all photographers want to go home with something. Anything.

This bright little path rising up through a small wood spoke to me one recent morning when the birds were basically giving me the middle feather. Despite my plaintive “where? where?” cries, no mercy was shown me, and so, when all others were riveted to the ground, binocs trained on some divine sight, I turned about 180 degrees the other way and found a golden moment. The very best thing about being out with birders is that, given their very deliberate (spelled “obsessive”) pacing, I can click away to my heart’s content without worrying that they will have moved on, or, God forbid, are tapping their feet waiting for me to catch up. No, I can shoot everything I care to, go out for coffee, return my morning emails, blink off for a quick nap, and they will very likely still be standing in the same spot when I return. Come to think on it, I wish I could have had this bunch with me on all those vacations when my kids kept asking me, “are you still taking pictures?”

Now, I have my own path.

atureAs you can see.

MIRROR, MIRROR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MUCH OF COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY IS DEPENDENT ON THE SPECIFIC SURFACES captured in its field of vision. We don’t just record light in a frame; we also record the particular properties of that light as it plays on a given subject. The dynamics of contract, reflection, texture and the way a surface sends light back to our eyes all weigh in the results. In broad terms, we can just simplify this to high light/normal light/low light, but in fact the results are far more nuanced.

In the two shots shown here for comparison, the metal distillery tanks at a microbrewery bear the distinctive stamp of the kind of light they are reflecting back to the camera. One is taken with natural sunlight pouring through the room’s skylight, while the other is lit completely by ceiling fluorescents after nightfall. Both were taken on the same white balance setting, i.e., “natural light auto”, making the two exposures at least neutral in how the camera processed what it saw. But what a contrast in the color registration of the two.

The daylight shot shows highlights in the steel of the tanks that runs to pale redness in some patches, while the night shot reads very dark blue with hints of green here and there. The results are certainly no big surprise to those who take multiple exposures of the same surface, say, a mountain lake, under changing light conditions. The dominant hues are dictated by how the surface of what you’re shooting decides to bounce back light. It’s not merely the difference between “light” and “dark” but, specifically, between the changes in tonal registration creates by the surfaces themselves. If these tanks were made of cardboard, for example, their light-bouncing properties would be drastically different than those seen here. Why does this matter? Well, it goes to the intended result. You have some control over how you visualize a scene with a camera, but Nature often has the final say. Understand light better, and you shoot smarter. And perhaps smile more at the end.

FUZZY LOGIC

By MICHAEL PERKINS

When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less”

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland

PHOTOGRAPHERS DISAGREE ABOUT NEARLY EVERYTHING. That’s to be expected, given that we are, as artists, all on such very individual trajectories. How can we reach consensus on what makes a picture “work”? Or what constitutes a “composition”? Or “realism”? Sometimes we cannot even find common ground on what very common terms about photography even mean.

Take the terms focus and sharpness, both of which can be used to define the resolution in an image. Both words are an attempt to measure something, but exactly what? And in whose view are these terms either final or arbitrary, anyhow? I make a very simple distinction between the two, and it helps me to keep my own thinking more organized. For me, the word focus is less about definition than it is about where I want the eye to be directed within a frame. In fact, most dictionaries’ first definition of the word is “the center of interest or activity.”, which to me means the place where the story should be happening. By comparison, sharpness, to me, speaks mostly of the distinction of fine details in a photo. Focus can mean sharpness, but, in my workflow, these contrasting connotations are helpful.

Thinking of the two terms as complementary to each other gives me a fairly consistent way of prioritizing them in a photograph. Focus, then, speaks of where I want to direct the viewer’s attention, while sharpness refers to how detailed I want that focal object to be rendered. In the image above, the focus of the narrative is obviously the two blurry children running into the frame. I could have made the adjustments necessary to make them as sharp as the figures in the background, but recording their speed seemed important to me, and so I anchored the general picture in sharpness to enhance the kids’ role as the picture’s focus. Make sense?

Doesn’t actually matter. You will define terms as befits your own approach to your own work. How can you do anything else? The take-home: don’t let anyone tell you that there is something like a fixed rule in photography. Of course we’ll disagree. Of course we’ll argue. But what takes us beyond argument is whether the results validate our approaches. The rest is noise.

LOOKA HERE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

INSIDE EVERY PERFORMER, THERE LIES a little kid dying to get his mother’s’ attention. teetering on tiptoe atop a picket fence against every rule of grace or gravity, just to hear a weary, “that’s nice, dear.” This urge to, basically, not be ignored follows us through every social situation, from religion to politics, but never so fundamentally as when we are putting our very personality up for sale. Here. Look here.

Look here NOW.

Like all too many human drives, the fine art of “doing anything to make someone glance in our direction” has undergone a change. Call it a refinement. Call it progress. Whatever the cause, the way we beg someone to please, please look here has become more sophisticated, more mechanized. Shouting fire in a theater used to be more than enough to make someone crank their head in your general direction. But in nearly the third century of mass advertising and media, the old sensation of, let’s say, being drawn into a tent by a carnival barker, has been replaced with multi-million dollar theme parks and scientifically-designed ad campaigns tuned to the finest mental and emotional bait. Merely reacting to someone acting loud and weird is just too simple, too slow.

That’s why it’s great for experience, and for photography, when some of the oldest tricks somehow still do work, when someone with a crude banner, loud colors, tinny music and a snappy, weird line of gab manages to cut through the clutter. A little miracle. Months ago, I found myself on a carnival midway for the first time in more than twenty years, and I was amazed to find how much my inner eight-year-old still enjoyed being conned, cajoled, begged for attention. Somehow, even in a world where a single roller coaster can take ten million dollars and ten years’ research to create, one guy in loud clothes and stupid wigs can make us, however briefly, replay to the old invitation hurry, hurry, hurry, step right this way. And maybe snap a picture of the vanishing art of “looka here”.

And, now, if you’ll all come in a little closer, just a bit closer to the stage….

RANDOMNESS, ON WHOSE TERMS?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FORMAL SHOOTS BY WORK BY PHOTOGRAPHERS, both in studio and on location, walk a strange tightrope, hybridizing the feeling of having captured “real life” in mid-step alongside the craft of making it look just a little better than real. We accept, for example, that the portrait shooter, with his bounce lights and backdrops, renders a more balanced or idealized version of us than truly exists in nature. In fact, we count on it, making comments like “make me look good!” during the process.

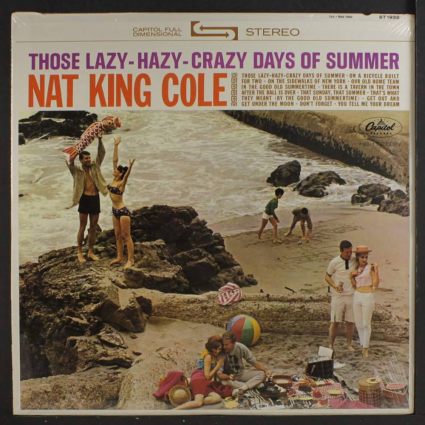

So deeply entrenched is this sense of formal, commercialized composition that, in our own work, we can’t help but see after-images of all that photographic salesmanship, no matter how bold or visionary we believe our stuff to be. I’ve now been around long enough to see re-runs of themes or techniques from many other sources creeping into my own, whether or not I’m trying to do a tribute or homage. My mind just has such a vast file of visual reference points from films, magazines, or culturally key moments that hints of at least some of them can’t help bleeding into my own, “original” pictures.

Often this happens without my recognizing it, at least at the instant I’m making an image, as the influence of an earlier photo informs something that I assume I’m creating wholly out of the moment. The seemingly random snap you see up top, of fun-seekers on the coastline of La Jolla, California is both of the moment and an echo of moments past, back whenever I first formed a mental diagram of what “a day at the ocean” should look like. Three weeks after I shot it, a snatch of an old Nat King Cole song brought up the memory of the album cover that was used to market that tune. The staging of that studio shoot’s “caught in the moment” ambience makes even a “candid” shot go through some sort of filter in my head. The gestures should look like this; the bodies should be arranged thus; The frame should be here.

In photography, there is no such thing as a “good” or “bad” influence, only influence itself. We make believe that we are stopping time inside a box in a way that is truly random, but it is actually experience which decides on which terms that randomness is applied.

NO, REALLY, GOOD BYE. I MEAN IT.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY FATHER USED TO DEFINE “OLD SCHOOL” ENTERTAINERS by how many bows or encores they took at the end of a given performance. The vaudeville-era concept of a “curtain call” was illustrative both of the showman’s natural inclination to stick around, drinking in a little more applause, and the audience’s reluctance to let those wonderful pied pipers get away, abandoning us to our regular humdrum lives. There’s something in those feelings that speaks to a need for photographs, and photographers.

A year ago this month, Marian and I closed the book on over twenty years in the same house, as well as its accumulated baggage and bloat. Estate sales were staged. Decades of memories were sifted, often jettisoned at a speed that astounded both of us. And most importantly, some key objects were committed to photos. Children’s art projects; historic front pages; and, in a kind of “Rosebud” moment, one more “curtain call” for a life I left half a century ago, symbolized by a curio that had been dragged with me from house to house since my salad days; an inoperable radio from the 1930’s.

The Philco Junior cathedral model shown here was already an antique in 1972, when my best friend at the time toiled at great length to refurbish it as a wedding present for me. The vacuum-tube guts of the thing had proven beyond repair, and so he had replaced the workings with a transistor-based tuner of his own design, then provided power to the front-mounted tuning “spook light” with alligator clips and a Ray-O-Vac lantern battery. Fortunately, the cloth speaker grille was intact, as was the tortoise shell trim and two-tone face plate. And so, to the naked eye, the Philco was still in good working order, occupying an honored place in the first apartment I and my young bride moved into after our budget nuptials.

ntiquesBy the time I snapped one more image of the front of the radio, just ahead of our leaving for California, the back had rotted away, the sides were splintered, and it hadn’t received a broadcast in over a generation. Moreover, that first marriage had long since vanished beneath the waves, as, sadly, had the friendship that sparked the initial radio project. In the spirit of Bogie’s “we’ll always have Paris”, I guess I can say that, in this image at least, I’ll always have the Philco. One more curtain call before we sign off for the evening, ladies and gentlemen, and be sure to tune in again tomorrow for…..

THE ELEGANCE OF THE INVISIBLE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE DECORATIVE ARTS SHARE A COMMON MISSION, which is to elevate the ordinary by re-imagining it, transforming things from invisible to elegant. Sometimes, of course, a sow’s ear cannot become a silk purse, no matter how much you fiddle with it, and not everything in the everyday can be glorified by the touch of a designer or shooter. Still, both disciplines can, often, confer some kind of absolute beauty on objects that we’ve been largely conditioned to ignore.

One of my favorite marriages of decorative arts and photography can be seen in the brief reign of what we now call Art Deco, although that term was coined decades after the movement sort of, well, moved on. Less extreme in its flowery ornamentation than its ancestor Art Nouveau, Deco gaily celebrated the furnishings of our daily lives, from parquet floors to wastebaskets to skyscrapers, making them some of the first industrially designed mass-produced objects of the Machine Age. meanwhile transforming consumption in the 1920’s and 30’s. At the same time, Photography was having its first Great Awakening, moving from a mere recording medium to an art form, one which, like Deco-designed works, could suddenly be copied and re-copied endlessly via film and print. The making of images that celebrated the ordinary as well as the extraordinary made for a unique amalgam of style and expression.

Just one look at a simple, typically invisible thing like a public mail drop box from the period (this one in daily use at the Hotel del Coronado in San Diego as of this writing) reveals a love of symmetry, of clean, budgeted lines, and a minimalist aesthetic that is about how a thing strikes you visually much more than what its actual function might be. Photographs can not only serve to capture these works before they vanish, but to do for them what they did for our most “normal” tasks, and that is to glorify them. Art Deco and photography have proven, over time, to be one of the happier marriages in the arts. And like all the best lovers, they never let the honeymoon end.

MARCHING OUT OF THE MURK

“We had the TOOLS, we had the TALENT!”——Ghostbusters (1984)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE CRY OF VICTORY BY EGON AND COMPANY when the dreaded Sta-Puf Marshmallow Man was defeated could easily be the enthusiastic “Yes!” uttered by many a photographer, once a stubborn technical problem has finally been solved and something like a usable picture results. The struggle is real, and it’s often just as sloppy and gooey as slaying a giant s’more. Being unable to nail an image through a failure of either ability or gear(or both) is as haunting as, dare I say it, a ghost, and exorcising the little sucker can be a true thrill.

One of the personal ghosts inhabiting my brain since 2011 was born the first time I stepped inside the legendary Hotel del Coronado, the lush 1880’s vacation spot in San Diego that stood in for a Florida resort in Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot (1959). The brilliant sunshine found just outside, on the joint’s sun porch, becomes a dim memory as soon as you step inside the lobby’s dark, wooded depths, a real catacomb of deeeeep shadow where light (and far too many photographs) goes to die. One look at my first attempt to extract something out of the murk, way back then, tells it all. The camera was a Nikon D60, a basic entry-level DSLR with a 10mp crop sensor and a fairly low ceiling for ISO. Exhibit “A”:

2011: Hotel del Coronado, San Diego, CA. f/2.2, 75mm, 1/60s., ISO 400. Shot on full auto.

Yeah, painful, innit? Now, jump forward about four cameras and fourteen years to my Nikon Z5 full-frame mirrorless, and, well, we almost have a fighting chance. Exhibit “B”:

Returning to the scene of the crime in 2025, and shooting manually. f/2.8, 28mm, 1/250s., ISO 2500.

Certainly, to extend the Ghostbuster metaphor, the “tools” are different; technology marches on. But the “talent”, if that’s not too obnoxious a word, has moved forward a bit as well. I am quite literally not the same photographer I was then, which makes sense, because I only had one direction I could go. If I still couldn’t make this picture by now, I should be spending my time planting zinnia seeds in the back yard or something. So what’s the pitch here? Something on the order of the old saw “never stop shooting”. It’s a musty, dusty, hackneyed slogan, but it just happens to be true. Make it til you make it right.