CLICKING WITH THE LADIES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

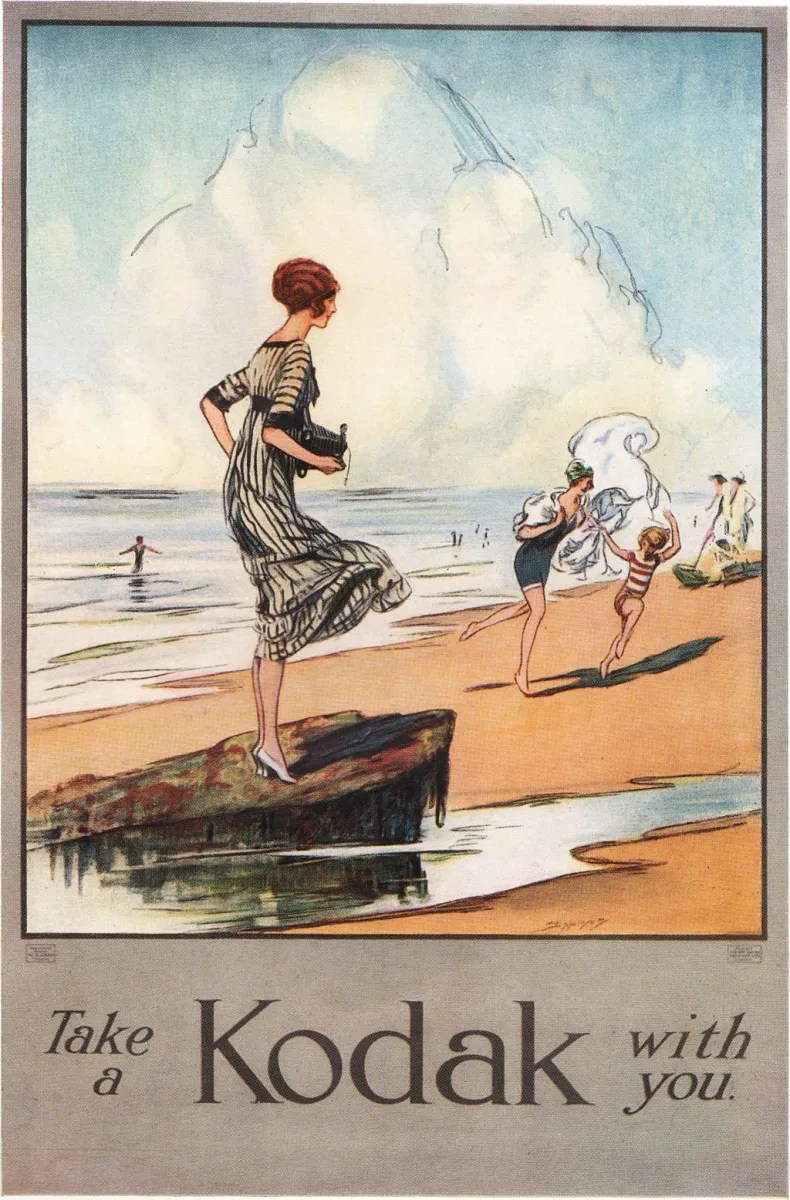

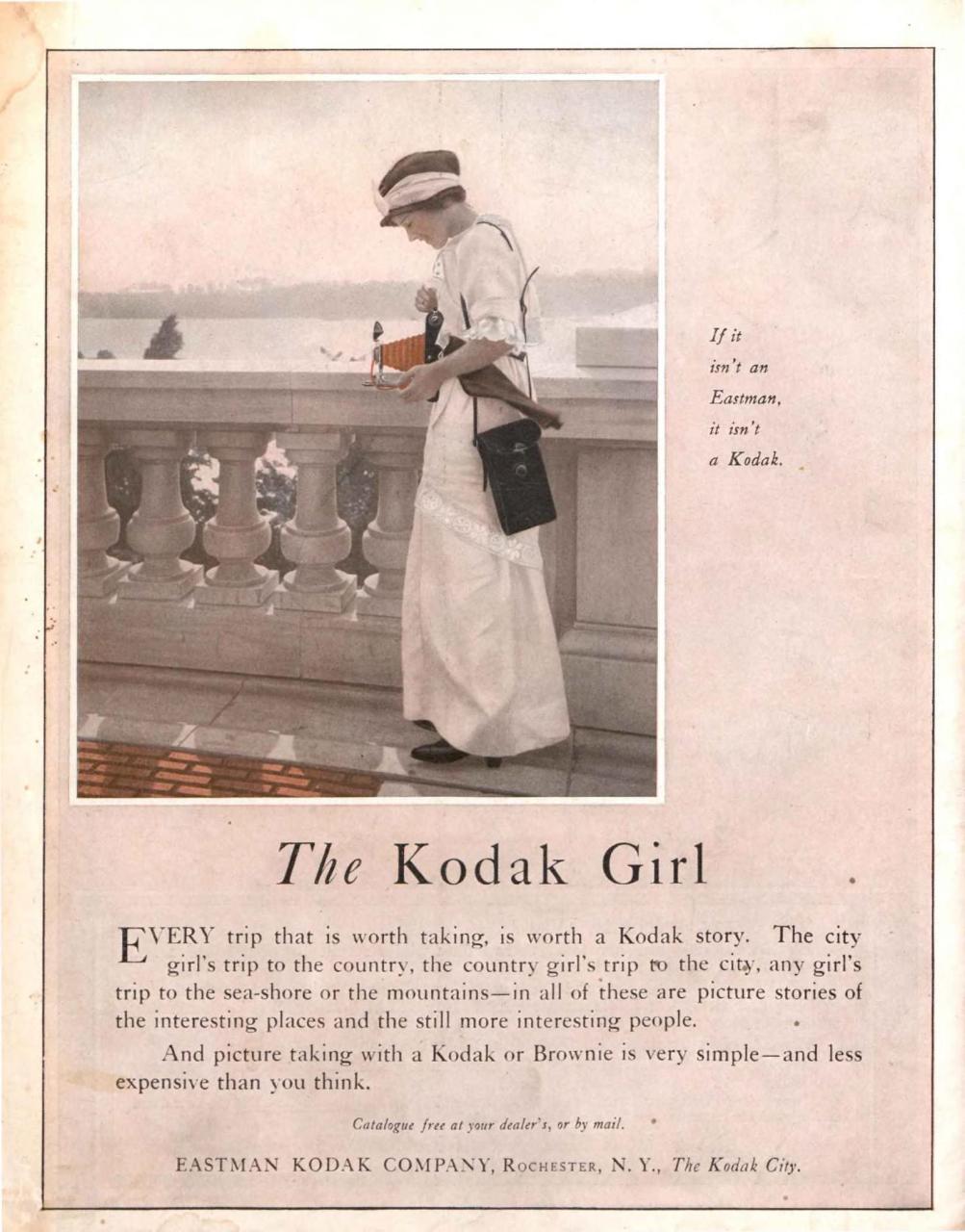

NO ONE ALIVE TODAY CAN RECALL A WORLD in which a camera of some kind was not considered an essential personal accessory, especially after the recent iPhone revolution has absolutely completed the “democratization” of photography. That concept, the idea that everyone should own a camera and take it everywhere, was, at one time, a novel idea, a behavior that had to be taught. And, as in so many cases with early amateur photography, the teacher for that habit was the Eastman Kodak Company.

Having already made cameras cheap and simple to operate by the end of the 19th century, the company next tackled the task of making people want to use them, and use them all the time. Kodak was certainly a “hardware” company, in that they made a wide line of cameras, but their bread and butter was as a “software” company, as it was the sale of Kodak film that created its biggest profit. And so, having provided the means for taking a lot of pictures, they turned to engineering the desire to do so, especially as regarded female consumers, where they saw their biggest potential growth.

Enter the Kodak Girl.

Young, adventurous, jaunty, and constantly pictured with a Kodak at the ready, The Kodak Girl was first featured in prominent women’s magazines in the late 1800’s, ready to preserve key moments at parks, the beach, and the mountains, as well as capturing key moments around the home. She was shown in a variety of poses and styles so as to appeal to both the stay-at-home mother and the active seeker, but her greatest role was as The Closer, a character with which consumers could easily identify, sparking their own decisions to buy their first personal camera and make its constant use a regular activity. Kodak kept evolving the Girl’s physical look as the 20th-century saw women gain in spending power as well as personal empowerment, modeling some ads in the ’20’s after silent screen actress Edith Johnson. Decades later, they would refresh the old campaign yet again, dubbing a young bathing beauty named Cybil Shepherd as a Kodak Girl for the age of Aquarius.

Thus, Kodak pioneered the idea of putting a camera in everyone’s hand a century before Steve Jobs added his own variation to the campaign, his iPhone removing the last real barrier to universal camera use. Introducing a truly useful thing into the world is a great talent, but the ability to convince people they need something they’ve never even thought to wish for is an equally remarkable skill.

THE DIVINE’S IN THE DETAILS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“IT HAD THE COOLEST CENTER CONSOLE….”

“REMEMBER THAT AMBER INDIAN HEAD AT THE FRONT OF THE HOOD?”

“THE ASHTRAY. IT WAS ALL CHROME. SO ELEGANT..”

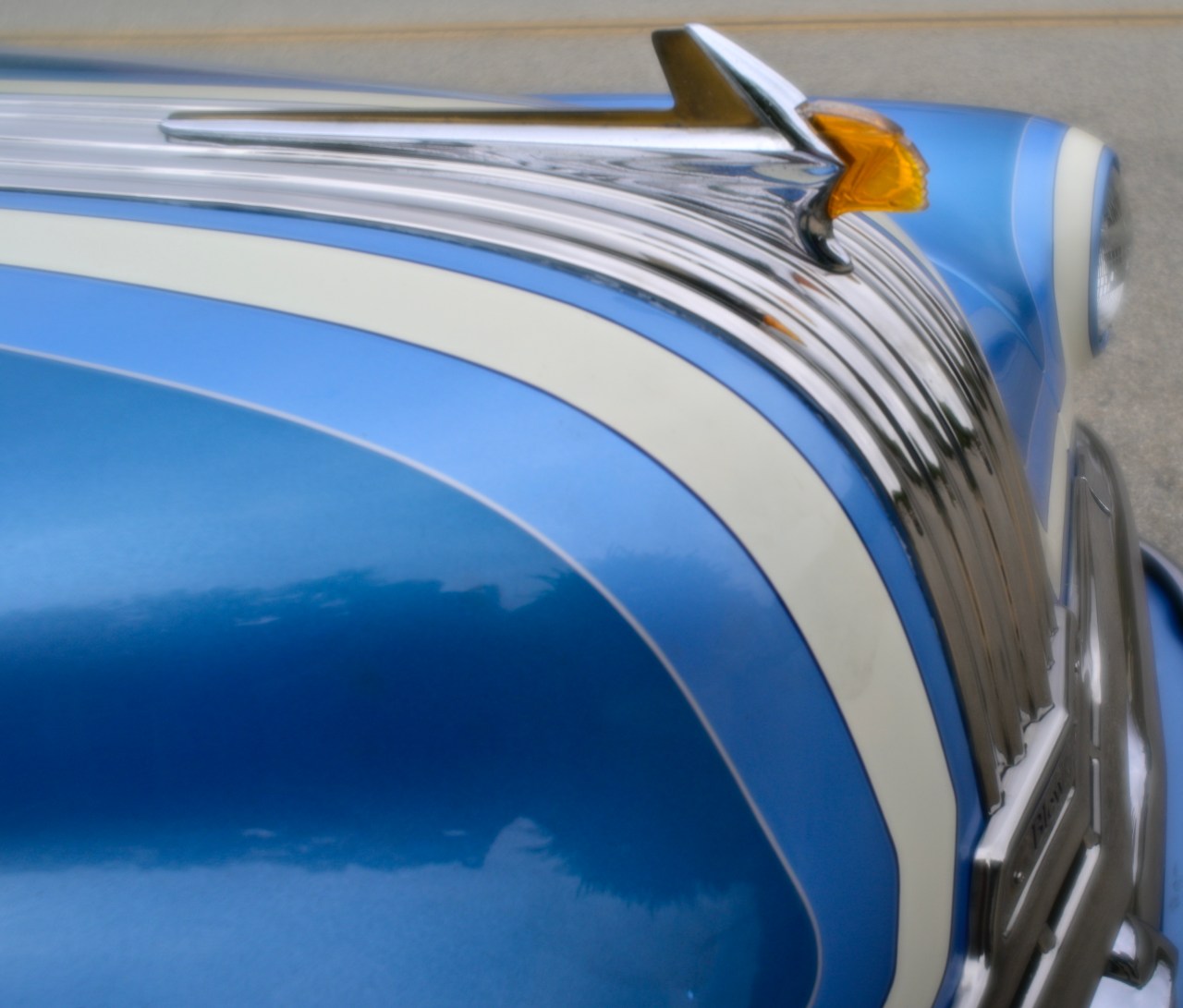

I HAVE PHOTOGRAPHED CLASSIC CARS AT NEARLY EVERY KIND of human gathering, excepting perhaps funerals and coroner’s inquests, and I have come to the conclusion that, while designers labor mightily to create sexy, muscular or lean shapes for the entire outer conception of an automobile, it is in the tiniest touches where the fondest user memories reside. Despite the best efforts of the boys at the drawing boards, many cars tend to look alike, like a lot a lot alike, a problem which is further exacerbated when a particular model becomes so successful that it inspires rafts of imitators. No, for the photographer in me, it’s the features, the add-ons, the ups and extras, that burn brightest in my memory.

I recently discovered a 1948 Plymouth Special Deluxe parked about three blocks from my apartment. It may have made an occasional street appearance here and there in the past, but, in recent weeks, it’s out nearly everyday, even though its owners live across the street and have a garage. Yesterday, I set about to pore over every inch of the monster, and, after a few full-on shots, it again occurred to me that the more delicate fixtures, the trims, the small and elegant accents…in other words, the real emotional bait that snags the buyer in the showroom, was what I wanted most to document.

The ’40’s saw the first head-to-toe use of chrome trim, but on a far more modest scale than the rocket-to-mars fins and grilles of the ’50’s. Still, the accent on cars, even in the first post-war years, was on decoration for its own sake. Most accent items on a car add no real function or performance edge, just coolness, and that’s just jim dandy with me. It’s like a big loop running in my head which explains my affection for something beyond its merely practical value; I love it because I love it because I love it, etc. Creature comforts and pure style determine our attachment to things across our lives far more than their actual function or use. And that makes even the most commonplace ride as pretty as a picture.

Dream Machines

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AT THIS WRITING, I HAVE JUST COMPLETED A LONG WEEKEND characterized by three really early morning treks to three consecutive birdwatching sites, a brutal trifecta of trudging and toil that has left me footsore and bent over, worn raw from bad shoes and the nagging shoulder weight of a five-pound telephoto. The weather, as is often the case along the Pacific coast, was iffy, which meant that the percentage of keeper shots plunged even further below my usually sorry harvest. It will take me another three days to sift through the raw takings, alternatively cursing the blown opportunities and over-celebrating the luck-outs. And so, as an antidote to that very long march, I have plunged into the only pure fun I gleaned during the entire ordeal.

Spoiler alert: it’s not a picture of a bird.

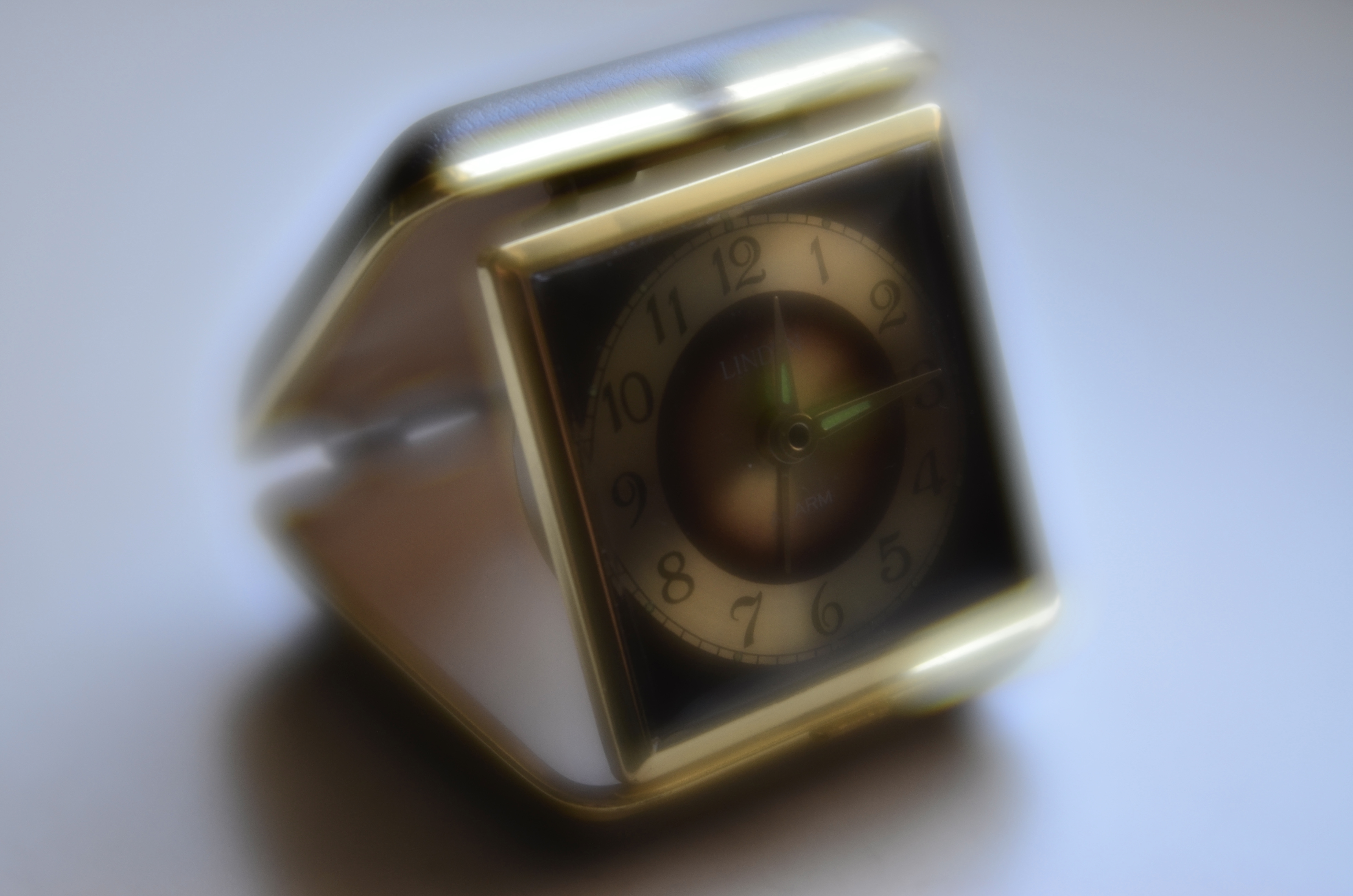

Well, in its day, it certainly soared like one. And, for me, limping several blocks from my apartment to visually make love to a supreme achievement in pure, seductive design, as an emotional balm for my aching’ dogs, it definitely made my heart take wing. I don’t know where this vintage 1940’s Pontiac Torpedo came from. The home where it was parked is, regularly, home to owners of elegant machines from bygone eras, usually of the pimp-my-ride-low-rider variety. One thing I do know is that none of these dream machines hang around for more than a few days. That made it Pilgrimage Time for me and my Lensbaby Velvet 28, which, shot nearly wide open, wraps its subjects in a dreamy haze that encases the focused image without blurring it. Watch the over-exposure on the chrome highlights, buy yourself some insurance with the use of focus peaking, and, voila, an express ticket to Hotrod Heaven.

I feel a little better equipped now to wade through three days’ worth of “maybe” images of birds while my knees and shoulder mend. I needed a quick dose of control, or at least the illusion of being able to make a picture instead of hoping I captured one. The fever’s broken now. But oh, what a delightful delirium!

ON MY WAY OUT…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

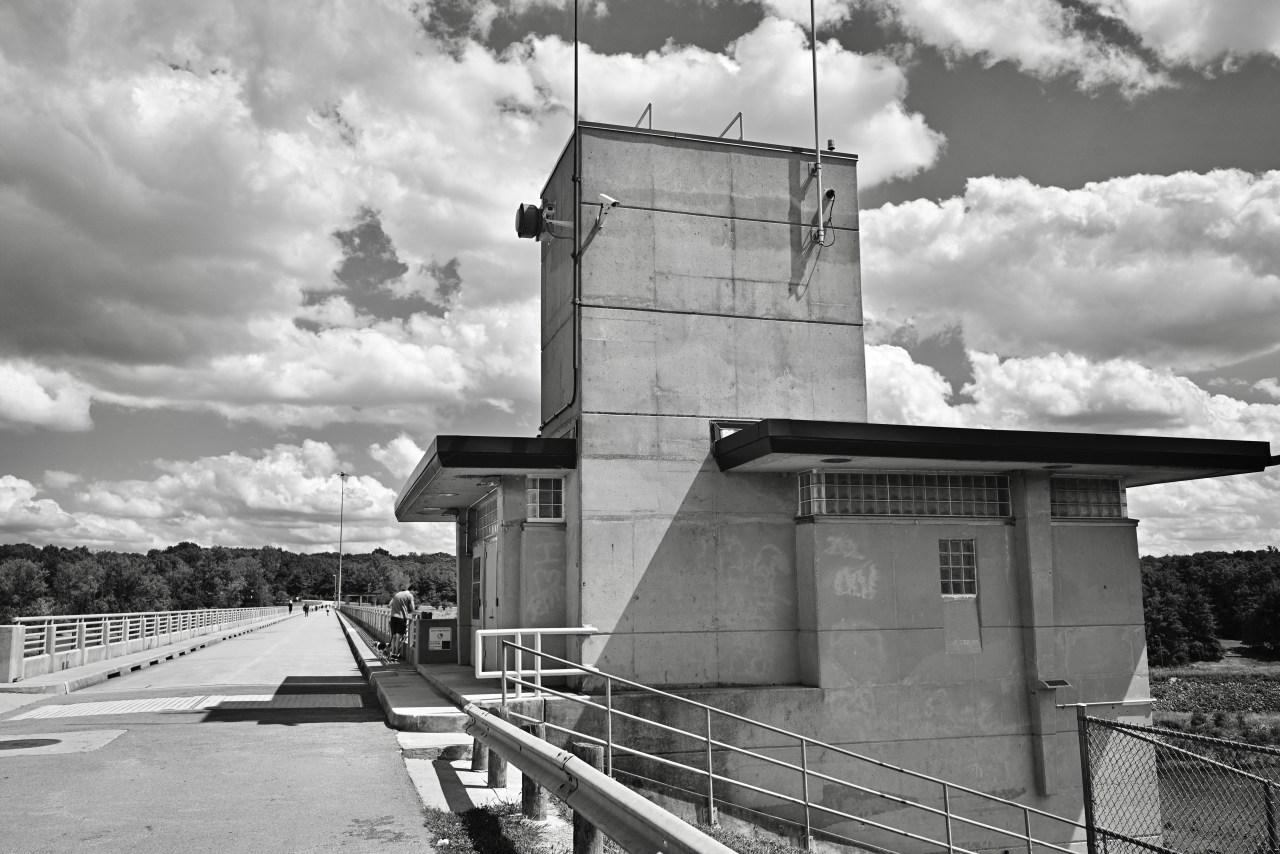

THE RECENT DEATH OF MY NINETY-SIX-YEAR-OLD FATHER actually resembled most visits I’ve made to Columbus, Ohio to visit him over the past quarter-century, in that a lot of my alone time was spent trying to reconcile the locales of my youth with the ghosts of things long vanished from those physical places. You can actually go home again, if you can bear the sight of things that you once thought were important, even vital, reverting to be just…..well, things.

No two people, certainly no two photographers, can regard the same scenes and come away with the same experience, and so we make fools of ourselves walking up to vacant lots and remarking to strangers that “there used to be a ball park here”. Not to the strangers’ eyes, certainly, and no longer even to us. Physical sites are imbued with only temporary meaning in one part of our lives, then revert to just their materials and geography once we stop needing them.

Nothing could be more ordinary than this simple arrangement of block concrete, which is adjacent to the spillway of Hoover Reservoir (not the more famous”dam”, nor the more infamous Hoover) on the northern edge of Columbus. Other than its role in providing some recreation and a clean supply of local drinking water, there is nothing visually remarkable about the place to the average photographer’s eye, and yet, to a seventy-three-year old just mourning the passing of a parent, it once held some special magic, and merited one last click.

When I was a boy, decades before farms and fields in the area would be swallowed by freeways and sprawl, motoring from my neighborhood to the Hoover constituted a half-day in the country. Driving our old Plymouth Savoy to the site meant a guaranteed stop at its rudimentary snack wagon (“food truck” for you kids) and a walk out to the spillway, where a thunderous cascade of water would explode forth from one of its release pipes and we kids would terrify our folks by leaning out over the low guard rail that barely separated us from watery doom hundreds of feet below.

I don’t know why I decided, after so many years of passing the reservoir on the way to somewhere else, that I needed one more up-close look. On this trip especially, I seem to have made several mini-pilgrimages to parks and wooded areas that once defined me, very aware that I was walking out of my old life for what now seemed forever. Of course, I will go back to Columbus gain, to see my sister, my adult children, my grandsons, and a dwindling network of old pals. But in some very real way, I was conscious that I walking out of some kind of door for the last time, with once-special places now returning to their normal uses as just more things in the world. A very strange kind of goodbye.

NO, REALLY, GOOD BYE. I MEAN IT.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY FATHER USED TO DEFINE “OLD SCHOOL” ENTERTAINERS by how many bows or encores they took at the end of a given performance. The vaudeville-era concept of a “curtain call” was illustrative both of the showman’s natural inclination to stick around, drinking in a little more applause, and the audience’s reluctance to let those wonderful pied pipers get away, abandoning us to our regular humdrum lives. There’s something in those feelings that speaks to a need for photographs, and photographers.

A year ago this month, Marian and I closed the book on over twenty years in the same house, as well as its accumulated baggage and bloat. Estate sales were staged. Decades of memories were sifted, often jettisoned at a speed that astounded both of us. And most importantly, some key objects were committed to photos. Children’s art projects; historic front pages; and, in a kind of “Rosebud” moment, one more “curtain call” for a life I left half a century ago, symbolized by a curio that had been dragged with me from house to house since my salad days; an inoperable radio from the 1930’s.

The Philco Junior cathedral model shown here was already an antique in 1972, when my best friend at the time toiled at great length to refurbish it as a wedding present for me. The vacuum-tube guts of the thing had proven beyond repair, and so he had replaced the workings with a transistor-based tuner of his own design, then provided power to the front-mounted tuning “spook light” with alligator clips and a Ray-O-Vac lantern battery. Fortunately, the cloth speaker grille was intact, as was the tortoise shell trim and two-tone face plate. And so, to the naked eye, the Philco was still in good working order, occupying an honored place in the first apartment I and my young bride moved into after our budget nuptials.

ntiquesBy the time I snapped one more image of the front of the radio, just ahead of our leaving for California, the back had rotted away, the sides were splintered, and it hadn’t received a broadcast in over a generation. Moreover, that first marriage had long since vanished beneath the waves, as, sadly, had the friendship that sparked the initial radio project. In the spirit of Bogie’s “we’ll always have Paris”, I guess I can say that, in this image at least, I’ll always have the Philco. One more curtain call before we sign off for the evening, ladies and gentlemen, and be sure to tune in again tomorrow for…..

AND IT WAS ALL YELLOW….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE LATE COLUMNIST PETE HAMILL ONCE DEFINED A “REAL” NEW YORKER as one who could tell you, in great detail, what a great town New York used to be. I was born in Ohio, but, as I married a woman who grew up in the city and its immediate environs, I have been privileged to visit there scads of times over the past twenty years, enough that I have been able to compile my own personal list of longings for Things That Have Gone Away in the Apple. There are the usual pangs for beloved bars and restaurants; bittersweet memories of buildings that fell to the unfeeling juggernaut of Progress; and the more abstract list of things that could be called How We Used To Do Things Around Here.

For me, one of those vanishing signposts of all things Noo Yawk is the great American taxi.

Take Me Uptown, October 12, 2024

As the gig economy has more or less neutered the cab industry in most cities, the ubiquitous river of yellow Checkers that used to flood every major NYC street at all turns is now a trickle, as Uber and Lyft drivers work in their own personal vehicles, causing one of the major visual signatures of life in the city to ebb, like a gradually disintegrating phantom. As much as the subway or sidewalk hot dog wagons, cabs are a cue to the eye, perhaps even the heart, that a distinct thing called “New York” endures. As a photographer, I’ve caught many huge flocks of them careening down the avenue over the years, even on days when I couldn’t, for the life of me, get even one to stop for me. Now, on a recent trip that was my first time in New York in nearly five years, spotting even one Checker was something of an event for me, and suddenly posed a bit of a photographic challenge.

The problem with taxis, now, is to show not only the physical object itself, but to visually suggest that it is slowly going ghost, fading into extinction. In such situations, I find myself with the always-tricky test of trying to photograph a feeling, finding that mere reality is, somehow, inadequate to the task. It bears stating that I am, typically, a straight-out-of-the-camera guy; I make my best effort to say everything I have to say before I click the shutter. That’s neither right nor wrong; it’s just the way I roll. And so, for me to lean heavily on post-tweak processing, I have to really be after something specific that I believe is outside of the power of the camera itself. The above shot, leaning heavily on such dream-feel, is even more ironic, because the Checker in question is no longer a working unit, but a prop parked permanently in front of a funky-chic boutique hotel. In other words, a museum piece. A relic.

Like moi.

Pete Hamill knew that New York’s only perpetual export is change. Managing that change means managing ourselves; knowing what to say hello and goodbye to; and hoping that we guess right most of the time on what’s worth keeping. Or maybe, just to forever hear a New York cabbie shouting over his shoulder to us, “Where To, Mac?”

STAX OF WAX

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO HAVE STRADDLED THE LINE BETWEEN DIGITAL AND ANALOG, doing most of their daily duty as dedicated pixel peepers but occasionally dipping their toe back into film, should certainly sympathize with those who, in recent years, have reverted to the comfort of dropping a needle onto a vinyl record, even if they themselves haven’t invested in a new turntable or a disc-washing device. Heading back to the happy land where experiences were a little more tactile can, indeed, be a lovely little side trip into comfort. For me, however, as a music lover who has long since divested himself of the bulk and maintenance of tangible tune storage, it’s not so much the worship of vinyl that interests me: it’s the places where the vinyl worshippers go.

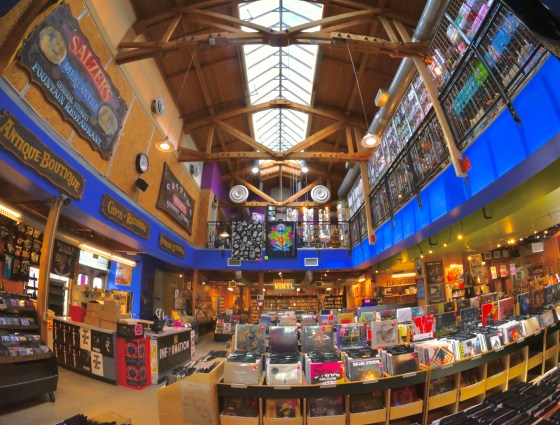

Salzer’s Records, est. 1966, Ventura, CA

One of the most welcome side benefits of the rebirth of records is a surge in dedicated record stores, not the measly music departments niched into Sears or Targets but places designed just to sell vinyl, and lots of it, along with bongs, t-shirts, and other headgear. The Sam Goodys and Licorice Pizzas and Peaches of the world may be long gone, but a new crop of repurposed shop spaces in re-gentrified neighborhoods is springing up in their place, alongside the few hardy survivors from the First Great Golden Age of Wax, such as San Francisco’s amazing Amoeba Records, Minneapolis’ Electric Fetus, and, as seen here Ventura, California’s Salzer’s Records, originally opened in 1966 and still so huge that, even using a fisheye lens, it’s impossible to show its entire two-story interior in a single shot.

Upon entering, you can smell the patchouli oil and incense, returning you either to your hippie roots or your favorite fantasy of what that era might have been like, depending on your age. Most remarkable from a photographic point of view is that the elder LP shops still exude the same energy as when we were all tender little flower children: the idea of music as but one component in a total immersion into creative energy, a tribal coming together of sounds, smells and sensations. Admittedly, it’s hard to capture all that in a camera, but, like blindly pulling out a random album from your library and slapping it on the turntable, you just drop the needle, and see what happens.

Far out, man….

PICTURES OF PICTURE TAKERS OF…..

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS SPEND A SIGNIFICANT AMOUNT OF TIME marking the passing of various elements of their world. We chronicle the end of stuff.

Things go out of fashion. The mass mind discards ideas or ways of doing this or that. And technology, that rocket sled of change, surges madly forward in ways that keep even the most alert shooter’s eye spinning like a top.

Film, as one example taken from our field, is always about to die off, never quite breathing its last, but rising from one potential deathbed after another, always in danger of winking out forever, never quite doing it. One thing that has, in fact, shrunk nearly out of sight, however, is the list of places where film can be served or processed. In my lifetime, dedicated film/camera stores were common elements of daily life, like post offices or drugstores. Now the holy temples where film still reigns supreme are vanishing into dust in favor of mail-in or online resources. And, on most days, in digital’s second quarter century, that’s usually enough to serve a solid but diminished analog audience.

Dexter’s Camera, Ventura, California, May 2024

But I am just sentimental enough to want to make pilgrimage to where the magic is still actually made, where emulsions and paper and controlled conditions combine to produce a tangible product. Even as I myself reserve film for special projects, I treasure a trip to an honest-to-God camera shop like an archaeologist yearns for a walk-through of Tut’s tomb. The image here resulted from my recent visit to Dexter’s Camera, which has done business at the same address in Ventura, California since 1960, with no end in sight. Well, nearly no end. As I write this, the business address of Dexter’s has moved a few blocks away, meaning that you are looking here at a physical photographic space which now can only be experienced, well, in photographs. Pictures of people and places that make pictures. Film is dead, long live film.

WE’LL TAKE A CUP OF KINDNESS YET

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S A TIME OF LIFE FOR DECIDING WHAT TO KEEP, and what to leave behind. Photographers, as well as people in general, reach an age when lists must be made. The essentials versus the disposable. The legacies versus the litter. We know we can’t take it with us when we go, but now things are getting serious, and so we can’t even take everything with us as we, say, move across town. Boxes are searched: offers are made. Do you want this? If so, take it. If not…

A year ago, this mug would never have made it into the keeper pile. I have often forgotten, over the years, that I even owned it, as it was one of those awkward gifts that an adult child gets from his aging mother simply because she has already bought him everything he actually wanted over a lifetime, and, oh, hell, here comes another Occasion. It’s kitschy and not my taste and was never on my radar as an object of desire. But a year ago, my mother was still alive, and so, now, it’s something quite different.

Now, the mug is bound up in things bigger than itself, having become a reminder that she loved that I loved that we were Irish. I was the one in my generation who “got it”, who thought that remembering our family’s journey from the Great Famine of the 1840’s to the present day was important, even an obsession, and so she wished up a token of that pride and sent it to me. I thought of you when I saw this.

And so, at this point, I make pictures of the mug, in an attempt to show a bit of the feelings that shape it in my mind beyond its mere physical reality. To interpret it as an aspiration, a remembrance, a ghostly vapor. Because my mother’s passing has not rendered the actual object any more valuable or artistic of and by itself. I am really taking pictures of myself from the inside out and draping that photographic veil onto the mug. In future, as the lists of keep/toss candidates pile higher and higher, the actual cup might well be left behind, but now that’s all right. In a photograph, I can continue to have something after I no longer possess it. That’s the miracle of a camera, and the best way to remember a woman who believed in, and often brought about, miracles of her own.

THE FACTUAL / ACTUAL FAULTLINE

Back When The Browns Lived On Main, 2022

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I RECALL A 1972 INTERVIEW WITH A PROMINENT ROCK CRITIC in which he confessed that, three years into the new decade, he was just getting used to the idea that the 1960’s were “going to end”. Not the idea that they were already over. No, he was even wrestling with the concept that they would ever be so. Such is the plastic quality of our sense of time. In some moments, it seems like the things we’re living through will continue forever, while, at other times, it seems like everything, everywhere, is already past. This yo-yo-ing sensation plays hell with our emotions, and, in turn, with the pictures we attempt to create with transient subjects. At least, that’s what happens with mine.

One situation which gets my own internal yo-yo spinning involves making images of small-towns life, which always sets me careening between the sensation that I’m both experiencing something that’s truly eternal and, simultaneously, something that’s as gone as the dodo. Standing on the simple main streets and leafy, sleepy lanes of the villages and burgs that have so far outlasted the twentieth century, it’s easy to be assimilated into the place’s slower rhythms, to briefly be lulled into thinking that it’s really the rest of the world that is imaginary. But then there is the rude shock of walking past a 1940’s drug store, complete with lunch counter and soda fountain, and bumping into a place that repairs iPhones. For a second, nothing makes sense. The two “realities” do, of course, co-exist; however, we are aware that the relics of the earlier era have essentially overstayed their welcome. They are living on borrowed time, the same borrowed time we, as photographers must now use wisely before….before…..

The surreality of shooting in small towns dictates the look of my pictures of them. I tend to use exaggerated tonal ranges, soft, painterly looks and dreamy art lenses on them, rather than merely recording them with the sharpness and balanced exposure of mere documents. As their very actualness is now so fluid in my mind, I prefer to see them as in a dim vision or imperfect remembrance. They seem more poignant for being less fixed in our regular way of seeing.

Like the 70’s reporter that couldn’t imagine his “time” ever coming to a close, I wrestle with the task of depicting worlds that are rapidly receding into the realm of memory. Oddly, making them look less literal bolsters their reality to me. For, like that reporter, I can’t imagine that they are ever going to end, and that dictates how I tell my camera to see. At that point, the machine, the instrument, is as unreliable a narrator as my own memory, just as it’s also made more reliable to my heart.

P.O.C. x 2

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NOSTALGIA, AS YOGI BERRA FAMOUSLY REMARKED, ain’t what it used to be. Photography often feeds on a longing for the past, either in the artificial retro-rendering of the way we used to capture images (think faux tintypes), or an affection for the actual life events we chose to preserve Back In Der Day (see every old shoebox of snaps you own). And now, in an unusual twist, Gen-Z shooters are experiencing their own time-specific manifestation of this pleasant pang, focusing on the very beginning of the digital era.

Suddenly a significant number of media influencers and Instagram mavens have turned away from cell phones as their default cameras and re-embraced the earliest days of pixelated point-and-shoots. Raiding Mom’s junk drawer for a working Canon Powershot or Kodak Easyshare, a growing number of Z-ers are seeking the lo-fi tech that accompanied many of their most important personal memories, peppering their online feeds with uploads of delightfully (and intentionally) flawed photos. So try to track this, history lovers: we have gone from film cameras to primitive digital cameras to more advanced digital cameras to remarkably advanced phone-based point-and-shoots back to primitive digital…all in the service of (sing it with me) Memories…light the corners of my mind…misty, water-color memm…...(ahem, sorry).

In some ways, this mini-trend echoes the fascination many young hipsters have long held for analog film as well as the crappy cameras that make them look even more, well, filmic, as if the technically derelict pics that emerge from them are somehow more tactile, more authentic than those from the latest iPhone or Android. And while I understand this desire to return to some Eden of lost youth, I cannot truly share the sensation.

I mean, look at this thing.

Behold my first-ever digital, a p&s from 2001 that boasted a Herculean 1.3 MP in raw, beefy picture power. For those of us who’ve forgotten the math, that’s a whopping 1280 x 960 worth of resolution, not exactly the stuff of dream enlargements or even decent screen quality, but hey, the picture’s ready right away (hear me talkin’, oh Polaroid pioneers!) Such cameras were, to the first generation of digi-users, a P.O.C. (proof of concept) that was also a P.O.C. (piece of crap). Full disclosure: my actual D-370 has long since disintegrated in my hand, meaning that I had to scan the interweb for an image of it. And yet, with such devices, say the young-un’s in the Then-Was-Better movement, I captured my prom, I chronicled our rafting trip, we giggled through Graduation Day. The remarks of one of the uber-young who are re-experiencing their salad days says expresses the sensation thus: “I feel like we’re becoming a bit too techy. To go back in time is just a great idea.”

Pardon me if I restrain my giddy joy.

I never took a technically acceptable picture with this peashooter, and I ran into the welcoming arms of my first DLSRs with unbridled optimism. Now, it could be argued that I finally can take technically acceptable pictures, but haven’t yet learned how to breathe a soul into them, but that’s a confession for another time. Some of those returning to first-gen digitals claim that the experience is one of simplifying or slowing down their picture-making, and on that count, I wish them godspeed. Whatever (and whenever) it takes to make a picture you love, from daguerreotypes to Kodachrome, you do you, and ignore all the old sods that say Don’t.

OPEN ME FIRST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NEAR THE END OF EVERY YEAR, SINCE ITS INCEPTION, The Normal Eye has cast a fond eye on the romance that persisted for nearly one hundred years between the Eastman Kodak Company and the worldwide market for amateur photography, a market it almost singlehandedly created. These posts have also included a nostalgic nod toward the firm’s famous Christmas advertising, which regularly instructed recipients of a new Kodak camera to “open me first” on the big day. Because before George Eastman could successfully put an easily operated and affordable camera into the world’s hands, he first had to answer the question, “but what will I use it for?”, a question with a very single answer: memory.

Like every savvy marketer, Eastman knew that he not only had to teach people how to use his simple new device: he had to teach them to desire it as well. Memories were the bait. As the world first learned how to say “Kodak” (A nonsense word Eastman devised to stand for nothing but itself in any language), it also had to be sold on its most compelling use, that of a storage medium for humans’ most treasured experiences. Aided in the late nineteenth century by the infant art of mass market advertising, Eastman pitched the camera as the new, essential means of not just recording important events but conferring importance on them. A gathering, a party, a wedding, the family dog at play…these were not really memories at all, unless and until a Kodak anointed them as such. It was a new way for the world to regard its experiences, not as valuable by themselves alone, but valuable because a Kodak, one’s own Kodak, had captured them. Today, we still react to life with the same urgent need. This will make a great picture. I have to get a picture of this.

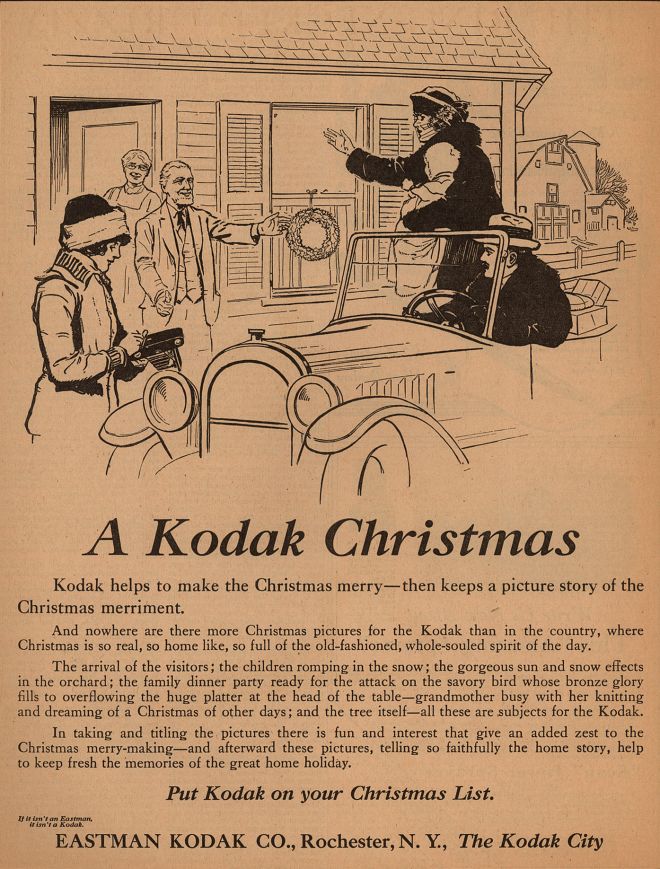

Advertise photography without using a photograph? Hey, welcome to 1900, folks.

And what could be a greater potential harvesting ground for these memories than Christmas Day? Almost from Kodak’s beginnings, Eastman mounted annual ad campaigns that emphasized how precious, how fleeting were the moments of joy and discovery that accompanied the opening of presents, certainly when those presents included a new Kodak camera. As seen in the above image, this sales pitch started even before most major newspapers could even reliably reproduce a photograph of any kind in their pages, leading to ads that touted the benefits of photography with only drawings or paintings of the product being used! Talk about the power of suggestion…..

The marketing of any product, from the automobile to the iPhone, starts with the engineering of desire, of convincing consumers they need a thing and then selling it to them. With luck, the buyer sees that they do, indeed, “need” that thing (even if they never knew it before), and come to think of it as indispensable. And so it was with the ability to freeze time in a box. As in Eastman’s time, we still see the value of those boxes, even as their functions have shifted and evolved. We still want the magic. And the trick is still enchanting. Every. Single. Time.

BACK TO THE BLUE PLATE

The lunch crowd at Beach House Tacos, Ventura, California, 2022

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A KIND OF ROMANCE, CALL IT A CULT OF THE INDIVIDUAL, that informs our love of what can only be called The Great American Joint. We have a special affection for the one-location, one owner store or restaurant that outlasts global competitors. We revel in diners that celebrate “100 years at the same location” or burger stands that offer only one house specialty (no substitutions!) And it is altogether appropriate that Americans, in particular, should hold the Moms-and-Pops of the world dear. After all, we did everything we could to put them out of business.

The multiple-location business model was actually born in the U.K. in the 1700’s but really hit its stride in the States in the1860’s when a local New York tea shop owner opened multiple branches around the city. By 1900, The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (or the A&P to you) became the first true grocery chain, and from there, the chain movement exploded to include hardware and department stores, hotels, clothiers, drugstores and, most importantly, restaurants. Over a hundred years later, chains offer familiarity and reliability as we move from one golden arch to the next, but they also starve the landscape of variety and, worse for photographers, distinctive visual experiences.

That’s why I doggedly seek out joints when traveling and shooting. The food varies wildly in quality, and that’s just fine: one man’s uncertainty is another man’s adventure, if you like. Beyond that, joints offer the chance to celebrate the different, the odd, the innovative. Chains are all about guaranteed outcomes. With Bob’s Crab Shack or the Keep Portland Weird Cafe you never know what you’ll get, and, for the sake of the pictures, unpredictability is a strength. And, in terms of karmic balance, it’s only fair that the country that tried to un-invent the private business learn, in its maturity, how to nurture what’s left. And if that means occasionally eating at a place where we have only one kind of burger, made daily on the premises, and when we’re out we’re out.….well, then, save me a seat. I’ll be with you as soon as I switch lenses.

FEEL CLOSE, SHOOT FAR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YEAR ONE WITH MY VERY FIRST CAMERA was a demonstration in pure randomness. Whatever passed directly in front of my $5 Imperial Mark XII got caught in the frame. Whatever wasn’t… well..

Without a doubt, I made some fumbling attempts at composition, but, at least at first, the idea that anything at all would show up on the film was so mind-blowing that my idea of “success” was a packet of prints that came back from the processor having registered basically any registration of color or definition. I was too busy being grateful for the miracle to nitpick the results.

This picture of my sister Elizabeth came from that period, probably the summer of 1966, and although it was, in execution and planning, a pure snapshot, it has brought a few souvenirs along with it as it’s travelled through time. It’s shot wide, but then, with a fixed-focus plastic lens loaded with aberrations, that’s about the only way she could have wound up even reasonably sharp. Again, I said reasonably. And so, even though she is prominent in the shot, it also took in a lot of incidental time-capsule information that is really only relevant to we two, all these ages later.

For one thing, the thoroughfare to her right, a two-lane country road out in “the sticks” at the time, is now an eight-lane feeder highway to Columbus, Ohio’s massive I-270 outerbelt. The creek she is looking into is largely invisible due to this expansion. Up beyond the horizon on the right is a densely forested metro park where we were taken for school picnics and field trips. It’s still there, but negotiating a service road to gain entry into it now requires a degree from MIT. And, of course, the only place you’ll find the autos that are touring back and forth is at either a museum or a classic car show.

When I’m away from this shot, it’s easy to forget a lot, like how going to that park was a “day in the country” for us at the time, even though it was hardly a twenty-minute drive from our house. Today, that “country” is a sprawling crush of chain stores, restaurants, and housing tracts, all of which have surged further and further eastward from the city’s core over half a century. And finally there is that face, that flawless, guileless, innocent face, still free of the scarring battles that would envelop us both over the course of our lives together. This week, this child turns sixty-eight, and I am about four hundred and thirteen or so, depending on which day you ask. But when my thoughts turn to my undying love for Elizabeth, I see this image, taken wide to include lots of temporal flotsam and jetsam, but shot just close enough to bring an angel into focus.

LAST NAMES AND OTHER FACES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN I WAS A CHILD, SEVERAL PICTURE BOOKS depicted the fronts of houses as if they were faces, with the windows roughly reminiscent of eyes, the roofline acting as a kind of hairdo, the door as the nose/mouth region, and so forth. One memorable Disney cartoon called The Little House gave benevolent and malevolent expressions to various buildings based on their role in the story. Skyscrapers always seemed to threaten: tidy, small cottages endeavored to charm. And so on.

I still think of the fronts on houses to be faces of a sort, or at least the house’s version of the public personas that we all adopt, the expressions we choose to present to the street as our visual signature. I love the design and detail choices that make a house’s face welcoming, or at times repellent, to those who stroll by. Additionally, when I can, I love to photograph neighborhoods where there is enough space between homes to allow for a kind of “last name” or second face for a house, based on what the less-than-primary things that are arranged there might hint at.

78 In The Shade, 2021

Such areas are often just a storage area for tools, from coiled garden hoses to rakes or wheelbarrows. Sometimes it features a backup building like a recessed garage or a shed. In these in-betweeny free-flowing spaces between homes, various gardening attempts might be made, unfinished projects may linger in limbo, or the space might merely be a small play area. In many cases, as in the above image, it also serves as a sneak peek to the neighboring streets that exist in their own special reality just beyond the rear of the lot.

The places we call home reveal more to the wandering camera than we suppose. Sometimes our attempt to protect our privacy from public view is, in effect, more revelatory than the chummiest welcome mats or bright flowers. Cameras help us in deciphering the codes by which we choose to engage with the world at large. The purely visual elements of those codes reward an extra second of a photographer’s curiosity.

TUCKAWAYS AND TAKEAWAYS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY GRANDMOTHER’S NEIGHBORHOOD STREETS were separated by alleys that ran between the rows of the area’s back yards, and, as a consequence, I have only a few memories of her actually walking between the fronts of houses along the main streets. Whether it was her hardscrabble childhood in Ohio coal country or her lifelong belief that people were always stupidly discarding perfectly good stuff, she always walked to market, the local drug store, or various friends’ places by way of the alleys. And if there is such a thing as a Bargain Junk God, it spoke to her along these paths, and so, we children were accustomed to her dragging home various treasures over the years, from scraps of lumber to fixable umbrellas to an entire kids’ swingset, complete with “glider”, which we adopted as our own.

Years later, armed with various cameras, I tend to channel her a bit.

Because people continue to throw away perfectly good stuff.

Every time I shortcut through an alley, I find at least one thing that may be in the process of being chucked out, or moved to make space, or replaced by something new, or just plain forgotten about…things that can, on occasion, make neat little narrative pictures. Take this self-contained coffee “business”, for example. It sits behind a strip mall in Scottsdale, Arizona, giving off strange vibes about its history, a history that, who knows, may not yet be complete. Is it an operating wheeled cafe? Was it put out to pasture when someone had a better idea or a bigger budget? Is the trailer to be repurposed, sold, or just headed for the scrapheap? At this moment in time all these plot lines are possible, and all conjectures are equally valid or equally nuts.

The speculation continues. What exactly IS “native” coffee? Is it just a name, or an actual niche market? Is the window just covered up with wood for protection, or is it, as the term goes “boarded up”? Is the trailer merely being parked here until its next day of operation, or are all of the Native Coffee fans of the world plumb out of luck? Funny thing is, all that daydreaming is fired by exactly one hasty exposure, made out of my car window as I trekked through A Place I’ll Never Be Again for God Knows What Reason, If Any. A picture may not literally be worth a thousand words, but it is often worth a thousand “what if” guesses about what’s happened or what’s about to happen. Photography locks in moments and frees the mind to story-tell. It’s enough to make me wish that Grandma, whom, it should be noted, actually bought me my first camera, had dragged a Leica home down the alley.

Just once.

BABY, YOU CAN DRIVE MY CAR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OVER TIME, PHOTOGRAPHY ACTS AS A VISUAL SEISMOGRAPH, tracking the jagged line between ourselves and the things we encounter in the world. The objects and conditions that we regard as “everyday”, and thus somewhat ordinary, are actually in flux all the time, as is our relationship to them. In making pictures of the world that surrounds us, we are always documenting how we, and the things we either carry or leave behind, are changing the terms of our engagement with one another.

In The Corral For Keeps, 2021

Consider the automobile, a thing that is at once a utility, a medium for art, an environmental threat, a source of nostalgic glamour, and dozens of other things that wax and wane alongside us as we weave our way through our lives. There is, simultaneously, nothing more mundane and nothing more amazing than a car. It is a thing we made and which we are constantly remaking, and now, may also be a thing we are desperate to unmake.

All of this process, whether we are journaling our changing attitudes towards cars or carbs, creates opportunities for the visual artist. Photographs create a timeline, and, in so doing, graphically map the highs and lows of our loves/hates for everything that we encounter on a daily basis. The fact that we may now be entering the age of the Unmaking Of The Auto is cause for sadness, relief, and memory, but, above all, it is a new canvas upon which the photographer can re-interpret this strange relationship.

The idea here is not to set everyone out to catalogue every car on the road. The thing is, any part of our daily life that regularly changes in relation to ourselves can feed our imagination and yield great pictures. For some of us, that’s a building. For others, the evolution of a favored face over time. Your journey, your agenda. Cars are only things among other things, after all. And yet, through our lenses and eyes, they become part of a narrative about us at our most personal. And the best narratives make the best photographs.

FORWARD INTO THE PAST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN HIS ESSENTIAL 1982 BOOK MEGATRENDS, the late John Nesbit, trying to predict the uber-changes that would eventually govern our present-day world, described a coping method, a law of compensation called “high tech / high touch”. HT/HT was a kind of social recalibration in which the feeling of dislocation generated by surges of technological advancement would be followed by movements that re-emphasized the comforts of the world just vanished. Think of it as a kind of emotional recoil, in which we spring back from forward leaps to the familarity of simpler times, such as the recent re-emergence of physical vinyl phonograph records as a reaction to the phantom musical realms of the cloud. Nesbit’s prophecy seems to have been realized in many such areas of our society, and photography has certainly seen its share of the phenomenon.

In the camera world, Nesbit’s “high tech-high touch” is a boomerang reaction to the digital era in picture-making, a time of enormous advances in the way images are recorded, manipulated and distributed. Indeed, as foretold in Megatrends, the past thirty years has seen a tremendous counter-revolution that, far from embracing a world that is bent upon perfecting the photographic process, actually rejects it, longing for a return to the very imprecision that defined the analog world, topped off, this time around, with a healthy dollop of nostalgia.

Digital photo sharing was no sooner off the drawing board than people began to pine for their old shoeboxes of physical prints, pictures “you could hold in your hand”. Cue the rebirth of the defunct Polaroid company and a return to instant analog photography, bad film, faulty lenses and all. Hate the coldness of binary storage? Enter the new passion for film of all kinds, aimed at an audience too young to remember how expensive and unwieldy it was, or how poorly built some bargain cameras had been. Coated with the sheen of yester-appeal, these shortcomings became pluses, hailed as “spontaneous”, “unpredictable”, or “delightfully imperfect” in the re-introduction of cheap old plastic toy cameras like the Holga (see above image) and, in turn, the creation of an underclass of all-new, technically compromised gear under the banner of the “Lomography” movement. Like your retro on the arty side? Welcome to the all-manual Lensbaby line, whose higher-end optics sold selective focus to a global fanbase.

A loving return to the imprecision and high failure rate of the film era became attractive to the creators of apps as well, and today, the insanely efficient cameras of the iPhone age sell millions of dollars of applications designed to simulate light leakage, expired film, high grain, lens flares….to, in essence, enshrine all the aggravations of the analog age as some kind of photographic golden oldies. We now praise the defects we used to spend tons of money to avoid. The scary uniformity of high-tech photography has come with a side of high-touch comfort food. It’s a little like Captain Kirk refusing the option of living in a world free of conflict, declaring, without irony, “I need my pain.” Perhaps the chance that something will go wrong is a needed contrast in a world where the likelihood of error has largely been engineered out. Neither precision or randomness is a guarantee of artistic merit, however: that, at least remains, as constantly as ever, in the individual photographer’s hands.

A REQUIEM IN NEON

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MY GRANDMOTHER CALLED THEM “THE PICTURE SHOW“, which I always thought was a more elegant phrase than the self-important motion pictures. Indeed, well into our second century of going to special, secret places to see illuminated instants stab across the dark to illuminate a wall and charm our collective senses, we are experiencing a sea change in every way that we refer to “the movies”, including how much of the experience is “picture”, how much is “show”, or even how much of that event is to be shared with others.

I came back across this image from 2015 as I was thinking about the reported demise of movie palaces, about the umpteenth such prophecy I’ve heard over a lifetime. Television, the death of the nuclear family, the scourge of home video, and now streaming and plague have all taken their place in conversations about how the movies, or at least how we consume them, are “finally over”. Who knows, this time out, it might finally be time to cue the end titles and think of these stories in some profoundly different way. What I do know is that, as the drama unfolds, cameras of all kinds need to be there, to chronicle the transition.

The theatre seen here is actually holding a gala on its last night in operation. It is closing, not because of hard times, but because of good ones, as the Harkins family, the most powerful name in movie theatres in the soutwestern USA, prepares to raze the Camelview Cinema to build an insanely larger version of it just across the street inside a mall. There will be speeches, local tv coverage, even a few tears. And the neon will dim and the attendees will become ghosts, just as this time exposure has visualized them. It’s a gloriously unsubtle night of Happy/Sad/But Mostly Happy.

Since 2020, this scene has been repeated all around the world as, for the first time, the future of theatrically projected “picture shows” is seriously in doubt. As I write this, only mega-blockbusters and “franchise” releases like the latest Marvel Masterwork are turning the turnstiles to any degree. Cocooning, before smaller screens, phones, and tablets, is still being driven by a strange cocktail of convenience and survival.

But many theatres won’t get the luxury of a Harkins sendoff, or even a poetic fade to black, merely the sudden, jarring contrast of Lights Out. In my grandmother’s day, going to the movies was still a bit of a miracle, a definite event. The houses were gaudy, resplendent in their excess, with even the boxy little bijous of her own small town fitted out in their own carnival colors. Part picture, part show. The road ahead in uncertain, but I want to seek out the ones that last the longest and the ones that wink out the saddest and everything in the middle, and snap my shutter madly until the last “flicker.”

DANCING WITH A STRANGER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE BEEN ORGANIZING A GIFT FOR MY SON’S FORTIETH BIRTHDAY, which is an overview of a specific photographic theme spanning the last ten years. A decade is a nice round figure, a handy unit of time for evaluating one’s evolution in various enterprises, and so the exercise has led me to go back the same stretch across my online image postings, but, instead of looking at the entire span of ten years, I became obsessed with throwing out the clutter from exactly ten years ago. I’d like to say it was a pleasant trip down memory lane, but, in fact, I’ve done most of it with one eye closed, all the better to minimize my cringing.

It’s more than sobering to look at the stuff you felt happy enough about to throw onto the interweb just a decade ago, almost like trying to pull off an intimate dance with a total stranger, and not a very good looking one at that. I am not trying to lead the world championship in false modesty when I say that the old delete button was looking quite shopworn when the job was done, and, if anything, I feel that the large pile of photographic detritus at my feet represents me being generous in too many cases where my sentiment overrode my sense.

You are, of course, a little bit alienated from your old self every new time you pick up a camera. Get enough distance between yourself and what you once thought was your “good stuff” and the contrast can knock you off your pins. Chances are, the You of Today sees composition, narrative, exposure and subject matter with a completely different set of priorities than the You of Yesteryear. That is, if you’re lucky. If you still regard your work of ten years ago as “all killer, no filler”, you may have spent the last decade walking in circles. Or you may be the greatest genius in the history of photography, in which case I’d like to become the local chapter president of your fan club.

Me, I’m pledging to re-edit my portfolio with a lot more regularity in the future. It may not be much more pleasant, but I’d rather face several dozens of my biggest misses at a time than legions of the suckers. In the meantime, I have that gift book to finish, and I’d better hurry up about it. If I think about it too long, I might just reduce the tome to a pamphlet and send my kid a coupon for a Happy Meal.