WORK AT A DISADVANTAGE

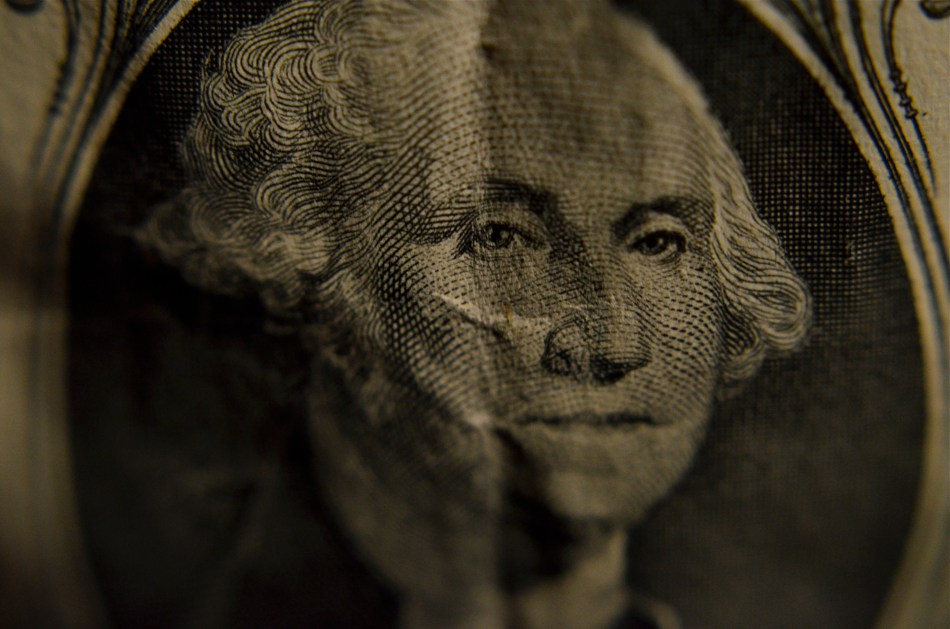

Focus. Scale. Context. Everything’s on the table when you’re trolling for ideas. 1/100 sec., f/5.6, ISO 800, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“IS THERE NO ONE ON THIS PLANET TO EVEN CHALLENGE ME??“, shouts a frustrated General Zod in Superman II as he realizes that not one person on Earth (okay, maybe one guy) can give him a fair run for his money. Zod is facing a crisis in personal growth. He is master of his domain (http://www.Ismashedtheworld.com), and it’s a dead bore. No new worlds to conquer. No flexing beyond his comfort zone. Except, you know, for that Kryptonian upstart.

Zod would have related to the average photographer, who also asks if there is “anyone on the planet to challenge him”. Hey, we all walk through the Valley Of The Shadow Of ‘My Mojo’s Gone’. Thing is, you can’t cure a dead patch by waiting for a guy in blue tights to come along and tweak your nose. You have to provide your own tweak, forcing yourself back into the golden mindset you enjoyed back when you were a dumb amateur. You remember, that golden age when your uncertainly actually keened up your awareness, and made you embrace risk. When you did what you could since you didn’t know what you could do.

You gotta put yourself at a disadvantage. Tie one hand behind your back. Wear a blindfold. Or, better yet, make up a “no ideas” list of things that will kick you out of the hammock and make you feel, again, like a beginner. Some ways to go:

1.Shoot with a camera or lens you hate and would rather avoid. 2.Do a complete shoot forcing yourself to make all the images with a single lens, convenient or not. 3.Use someone else’s camera. 4.Choose a subject that you’ve already covered extensively and dare yourself to show something different in it. 5.Produce a beautiful or compelling image of a subject you loathe. 6.Change the visual context of an overly familiar object (famous building, landmark, etc.) and force your viewer to see it completely differently. 7.Shoot everything in manual. 8.Make something great from a sloppy exposure or an imprecise focus. 9.Go for an entire week straight out of the camera. 10.Shoot naked.

Okay, that last one was to make sure you’re still awake. Of course, if nudity gets your creative motor running, then by all means, check local ordinances and let your freak flag fly. The point is, Zod didn’t have to wait for Superman. A little self-directed tough love would have got him out of his rut. Comfort is the dread foe of creativity. I’m not saying you have to go all Van Gogh and hack off your ear. But you’d better bleed just a little, or else get used to imitating instead of innovating, repeating instead of re-imagining.

SUBDIVISIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SPACE, BY ITSELF, DOESN’T SUGGEST ITSELF AS A PHOTOGRAPHIC SUBJECT, that is, unless it is measured against something else. Walls. Windows. Gates and Fences. Demarcations of any kind that allow you to work space compelling into compositions. Arrangements.

Patterns.

I don’t know why I personally find interesting images in the carving up of the spaces of our modern life, or why these subdivisions are sometimes even more interesting than what is contained inside them. For example, the floor layouts of museums, or their interior design frequently trumps the appeal of the exhibits displayed on its walls. Think about any show you may have seen within Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim museum, and you will a dramatic contrast between the building itself and nearly anything that has been hung in its galleries.

What I’m arguing for is the arrangement of space as a subject in itself. Certainly, when we photograph the houses of long-departed people, we sense something in the empty rooms they once occupied. There is fullness there inside the emptiness. Likewise, we shoot endless images of ancient ruins like the Roman Coliseum, places where there aren’t even four walls and a roof still standing. And yet the space is arresting.

In a more conventional sense, we often re-organize the space taken up by familiar objects, in our efforts to re-frame or re-contextualize the Empire State, The Eiffel, or the Grand Canyon. We re-order the space priorities to make compositions that are more personal, less popular post card.

And yet all this abstract thinking can make us twitch. We worry, still, that our pictures should be about something, should depict something in the documentary sense. But as painters concluded long ago, there is more to dealing with the world than merely recording its events. And, as photographers, we owe our audiences a chance to share in all the ways we see.

Subdivisions and all.

DRIVING THE IMAGE

YOU CAN FILL A LIBRARY SHELF WITH OPPOSING ARGUMENTS ON LIGHT’S ROLE IN PHOTOGRAPHY, not necessarily a debate on how to capture or measure it, but more a philosophical tussle on whether light is a mere component in a photograph or enough reason, all by itself, for the image to be made, regardless of the subject matter.

The answer, for me, is different every time, although more often than not I make pictures purely because the light is here right now, and it will not wait. I actually seem to hear a clock beginning to tick from the moment I discover certain conditions, and, from that moment forward, I feel as if I am in a kind of desperate countdown to do something with this finite gift before it drifts, shifts, or otherwise mutates out of my reach. Light is running the conversation, driving the image.

“In the right light, at the right time, everything is extraordinary”, the photographer Aaron Rose famously said, and I live for the chance to ennoble or, if you will, sanctify something by how it models or is embraced by light. Certainly I usually go out looking for things to shoot, but time and time again something shifts in my priorities, forcing me to look for ways to shoot.

The practical world will look at a photograph and ask, understandably,  “what is that supposed to be?”, or, more pointedly, “why did you take a picture of that?” This makes for quizzical expressions, awkward conversations and sharp disagreements within gallery walls, since our pragmatic natures demand that there be a point, an objective in all art that is as easily identifiable as going to the hardware for a particular screw. Only life, and the parts of life that inspire, can’t ever function that way.

“what is that supposed to be?”, or, more pointedly, “why did you take a picture of that?” This makes for quizzical expressions, awkward conversations and sharp disagreements within gallery walls, since our pragmatic natures demand that there be a point, an objective in all art that is as easily identifiable as going to the hardware for a particular screw. Only life, and the parts of life that inspire, can’t ever function that way.

We often decide to make an important picture of something rather than make a picture of something important. That’s not just artsy double-talk. It’s truly the decision that is placed before us.

Alfred Steiglitz remarked that “wherever there is light, photography is possible”. That’s an unlimited, boundless license to hunt for image-makers. Just give me light, the photographer asks, and I will make something of it.

DO SOMETHING MEANINGLESS

The subject matter doesn’t make the photograph. You do. A pure visual arrangement of nothing in particular can at least teach you composition. 1/400 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOOT WHAT YOU KNOW. SHOOT WHAT YOU LOVE. Those sentences seem like the inevitable “Column A” and “Column B” of photography. And it makes a certain kind of sense. I mean, you’ll make a stronger artistic connection to subject matter that’s near and dear, be it loved ones or beloved hobbies, right? What you know and what you love will always make great pictures, right?

Well….okay, sorta. And sorta not.

I hate to use the phrase “familiarity breeds contempt”, but your photography could actually take a step backwards if it is always based in your comfort zone. Your intimate knowledge of the people or things you are shooting could actually retard or paralyze your forward development, your ability to step back and see these very familiar things in unfamiliar ways.

Might it not be a good thing, from time to time, to photograph something that is meaningless to you, to seek out images that don’t have any emotional or historical context for you? To see a thing, a condition, a trick of the light just for itself, devoid of any previous context is to force yourself to regard it cleanly, without preconception or bias.

Looking for things to shoot that are “meaningless” actually might force you to solve technique problems just for the sake of solving, since the results don’t matter to you personally, other than as creative problems to be solved. I call this process “pureformance” and I believe it is the key to breathing new life into one’s tired old eyes. Shooting pure forms guarantees that your vision is unhampered by habit, unchained from the familiarity that will eventually stifle your imagination.

This way of approaching subjects on their own terms is close to what photojournalists do all the time. They have little say in what they will be assigned to show next. Their subjects will often be something outside their prior experience, and could be something they personally find uninteresting, even repellent. But the idea is to find a story in whatever they approach, and they hone that habit to perfection, as all of us can.

Just by doing something meaningless in a meaningful way.