FUNCTION OVER FORM

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY BEGAN MAINLY AS A MEANS TO DEPICT THINGS, to faithfully document and record. Those things tended to be fairly concrete and familiar; a landscape, a building, a locomotive, portraits, events. Later, when painting freed itself from such strictly defined subject matter, veering into ever more abstract and impressionistic areas, photography, too, found itself exploring patterns and angles that were less “about something”, tableaux that were interesting as pure form.

The industrial age created many installations and factories whose purpose was not clearly obvious at first glance, but as vast collections of pipes, ducts, platforms, and gear that, unlike commercial objects, didn’t at once reveal what their function was. They weren’t contained in stylish cabinets or hidden behind alluring packaging. They just were, and they just did. The arrival of abstract industrial photography was the perfect means for merely admiring the contour and texture of things, without the need for context or explanation. Edward Steichen, Walker Evans and other giants saw and exploited this potential.

That Day At The Plant, 2025

I find myself still drawn to the same aesthetic, as I enjoy walking into complex structures whose use is not immediately obvious. It’s not so much an attempt to imitate those earlier creators of pure form photography as it is to rediscover their joy in the doing. It’s an homage, but it’s also me trying to have a subject affect me in the same way it did for those who went before me. And, of course, with its refusal to use tone to explain or contextualize things, I prefer to do this work in black and white.

In the end, it’s just one more way to look at things, a way to shake up your expectations. You can’t surprise anyone else if you can’t surprise yourself. Forcing yourself to see in new ways, to reconfigure the rules for what a “picture” is, provides stimulation, and that, in turn, invites growth.

STRONG AT THE CENTER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EDWARD STEICHEN’S MAJESTIC PHOTO ESSAY The Family Of Man, which was first mounted in 1955 at MOMA as a curated exhibit and was then captured within one of the most essential reference books in all of photography, remains a essential document on the sameness and uniformity of human behavior across all social, ethnic and financial demarcations. It actually gives reality to the old saw that “we are all the same”, showing mankind in peace, love, war, ritual, youth, old age, birth, death and hope. It is a miracle project which I urge you to add to your collection.

One of the key elements of FOM for me is its depiction of the universal essence of motherhood. All the anxiety, risk, and courage displayed by all women in all corners of the world, all of them wanting to endure, to protect their children, to hand something on to the next generation of mothers. In my own halting way, I am always looking to capture some small something of the unique energy of mothers. It informs my street work in a way no other subject does. And, is often the case with candid work, you find more little miracles the harder you look for them.

And, sometimes, you get a gift.

Three years ago, during an ordinary visit to my wife’s son and his family, I had the occasion to observe both her and her daughter-in-law, gathered within a few feet of each other, each submerged within quiet worlds of their own making, Marian musing over a sinkful of dishes, Erin taking a breath between Momtasks. Both women possess faces which both reveal and conceal, making them irresistible for frequent visits from my camera. I know them both well and yet could never really, fully know them at all, making the next images of them magical with potential.

Perhaps that next shot, goes the delusion, will be the one that explains everything. Of course, this can never be the case, and yet I continue to click away into infinity in vain pursuit of the day when, as Frank Zappa used to say, The Great Oracle Has It All Psyched Out. Steichen’s Family Of Man is an exploration into what all of us share across our collective humanity. But you don’t have to wander the globe to see those commonalities. Sometimes, all you have to do is look across a kitchen.

LET THE LIGHT BE THE STORY

Ordinary, familiar objects, yes, but, for a few moments. their display of light was all the “subject” I needed. 1/200 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE THINGS I OCCASIONALLY MISS ABOUT WORKING WITH PRIMITIVE CAMERAS is that the terms of success and failure are so stark. As Yoda says, you either do or do not…there is no “try”. If you have a limited piece of gear, it will always be capable (or incapable) of exactly the same things. That argument is settled, and so you have to find good pictures where they naturally occur….truly thinking outside (or without) the box.

The fact that you will get little or no extra help from the camera is initially limiting, but also, in a strange way, freeing.

On the other hand, the better your equipment, the more opportunities you have to counter iffy lighting conditions in your subjects. Photography today is about almost never having to say, “I couldn’t get the shot”…..at least not because of a lack of sufficient light. It’s just one more imperfect thing that shooting on full auto “protects” you from. But the argument could be made that ultra-smart cameras give you an output that, over time, can be stunningly average. The camera is making so many decisions of its own, in comparison to your measly little button flick, that every shot you “take” is pushing you further and further away from assuming active control of what happens.

Early morning shadows shift suddenly, presenting many different ways to see the same subject. 1/400 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

Hunting for images that you could capture with virtually no “help” from your camera is a more active process, since it involves planning. It means looking for pictures that your camera may not be able to grab without your specific input. And one great way is to shoot images that don’t matter in themselves, so that you are letting the light, and not the subject, be the entire story. That, and shooting on manual.

Back yards are great because they are convenient stages for light tracking. You can see the light conditions shift over the course of an entire day. Better still, it’s familiar territory that can only become more familiar, since it’s so close at hand, and available anytime. Since you will have more “what am I gonna shoot?” days than “amazing” days over a lifetime, fill them up by giving yourself a seminar in “this is what the light does”. Believe me, something worth keeping will happen.

Early morning, just after dawn, is the best time to work, because the minute-to-minute changes are so markedly unique. Wait too long and you lose your window. Or maybe you’re there in just another few minutes, when something just as good may present itself. I also like to work early because, living in the desert, I will have hours and hours of harsh, untamed light every day unless I plan ahead. It’s just too retina-roastingly bright, too much of the time.

Edward Steichen taught himself light dynamics by spending months shooting the same object in the same setting. Hundreds, sometimes thousands of frames where nothing changed but the light. He put in the time taking scads of images he knew he would never use, just to give him a fuller understanding of how many ways there were to render an object. He benefited, zillions of frames later, when he applied that knowledge to subjects that did matter.

The greatest photographer of the 20th century became “that guy” because he was willing to take more misses than anyone else in the game, in order to get a higher yield of hits down the road.

Shooting just for a better understanding of light is the best photo school there is, and it’s cheap and easy in the digital age. No chemicals, no glass plates, nothing in the way but yourself and what you are willing to try.

I like the odds.

(follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye)

Related articles

- Street Photography Tips, Techniques and Inspirations (itscitrarizqinow.wordpress.com)

- How to break through the bottleneck of photography skills (ghjg85.wordpress.com)

I SEE YOUR FACE BEFORE ME

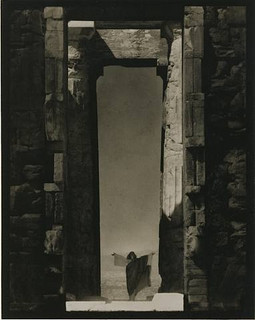

Edward Steichen’s amazing 1921 portrait of dance icon Isadora Duncan beneath a massive arch of the Parthenon in Greece, an image which recently surged to the top of my mind. See a link to a larger view of this shot, below.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE IMAGES SIT AT THE BOTTOM OF THE BRAIN, LIKE STONE PILLARS IN THE FOUNDATION OF AN IMMENSE TOWER.The structures erected on top of them, those images we ourselves have fashioned in memory of these foundations, dictate the height and breadth of our own creative edifices. Between these elemental pictures and what we build on top of them, we derive a visual style of our own.

In my own case,many of the pillars that hold up my own house of photography come from a single man.

Edward Steichen is arguably the greatest photographer in history. If that seems like hyperbole, I would humbly suggest that you take a reasonable period of time, say, oh, twenty years or so, just to lightly skim the breadth of his amazing career….from revealing portraits to iconic product shots to nature photography to street journalism and half a dozen other key areas that comprise our collective craft of light writing. His work spans the distance from wet glass plates to color film, from the Edwardian era to the 1960’s, from photography as an insecure imitation of painting to its arrival as a distinct and unique art form in its own right.

At the start of the 20th century, Steichen co-sponsored many of the world’s first formal photographic galleries, and was a major contributor to Camera Work, the first serious magazine dedicated wholly to photography. He ended his career as the creator of the legendary Family Of Man, created in the early 1950’s and still the most celebrated collection of global images ever mounted anywhere on earth. He is, simply, the Moses of photography, towering above many lesser giants whose best work amounts to only a fraction of his own prodigious output.

Which is why I sometimes see fragments of what he saw when I view a subject. I can’t see with his clarity, but through the milky lens of my own vision I sometime detect a flashing speck of what he knew on a much larger scale, decades before. The image at left recently rocketed to my mind’s eye several weeks ago, as I was framing shots inside a large government building in Ohio.In 1921, Steichen journeyed to Greece to use the world’s oldest civilization basically as a prop for portraits of Isadora Duncan, then in the forefront of American avant-garde dance. Framing her at the bottom of an immense arch in the ruins of the Parthenon, he made her appear majestic and minute at the same time, both minimized and deified by the huge proportions in the frame. It is one of the most beautiful compositions I have ever seen, and I urge you to click the Flickr link at the end of this post for a slightly larger view of it. (Also note the link to a great overview of Steichen’s life on Wikipedia.)

Uplighting creates a moody frame-within-frame feel at the Ohio Statehouse building, in a shot inspired by Edward Steichen’s images of massive arches. 1/30 sec., f/8, ISO 800, 18mm.

In framing a similarly tall arch leading into the rotunda of the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, I didn’t have a human figure to work with, but I wanted to show the building as a series of major and minor access cavities, in, around, under and through one of its arched entrance to the central lobby. I kept having to back up and step down to get at least a partial view of the rotunda and the arch at the opposite end of the open space included in the frame, which created a kind of left and right bracket for the shot, now flanked by a pair of staircases. Given the overcast sky meekly leaking grey light into the rotunda’s glass cupola, most of the building was shrouded in shadow, so a handheld shot with sufficient depth of field was going to call for jacked-up ISO, and the attendant grungy texture that remains in the darker parts of the shot. But at least I walked away with something.

What kind of something? There is no”object” to the image, no story being told, and sadly, no dancing muse to immortalize. Just an arrangement of color and shape that hit me in some kind of emotional way. That and Steichen, that foundational pillar, calling up to me from the basement:

“Just take the shot.”

Related articles

- The Photograph as a Social Statement (halsmith.wordpress.com)

- Picture Imperfect (andrewsullivan.thedailybeast.com)

- http://www.flickr.com/photos/quelitab/5793648357/lightbox/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Steichen