READING THE ROAD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

COMPOSITION IN PHOTOGRAPHY IS NEVER MERELY A MATTER of rearranging the deck chairs on the good ship Take-A-Snap. Yes, at first, there is the frame to be dealt with, and with that, the crucial decisions on what stays in and what gets left out. And then there is the front-to-back and side-to-side staging of the image, the visual coding you build into the picture to tell your viewer where to look and how to prioritize what he sees, a process influenced as well by contrast, depth of field, and other shooting settings.

But there is another crucial way to instruct the viewer’s eye on how all this information ranks within itself, and that is the decision to shoot in either color or monochrome. It’s true that, merely by landing on one or the other, you haven’t added or subtracted any visual elements that weren’t already in the frame. That is, you didn’t stick in four more trees or yank out the ocean shore. However, pictures in these two opposing modes convey information in distinctly different ways, and so both will confer certain qualities on the objects in the frame based on how the eye takes in that information. This can either make your picture pop with dimension or sink into murk.

Color assigns a rank to things and relegates objects to either shadow or light, foreground or background. Monochrome does this as well, but in a far subtler manner, meaning that some color shots which are clear in their message might appear muddled or muted when rendered in black and white. Conversely, something which is direct and contrasty in mono might appear either weakened or magnified in color.

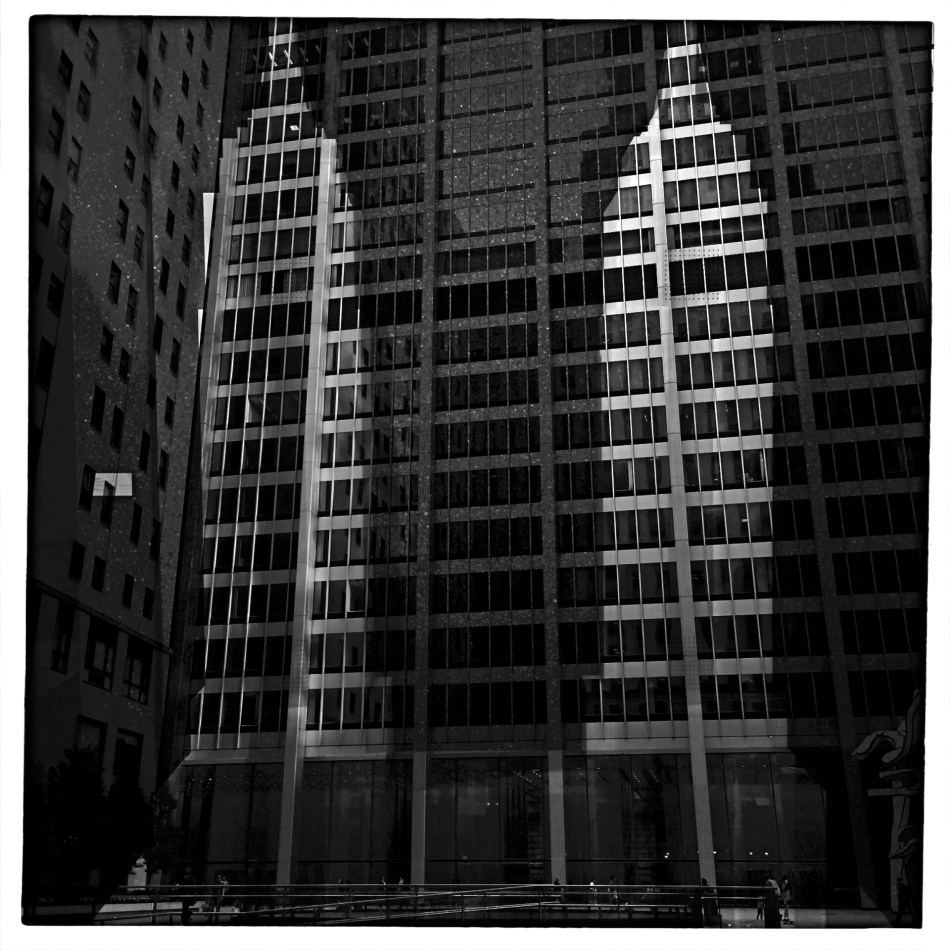

In the case of the two renderings seen here, the tangly busy-ness of the color shot (top) seems, in monochrome (above), to make a very dense photo much harder to read. There is so much texture in the color version that just becomes mushy in grayscale, so that the mono version does nothing to simplify the shot….quite the opposite. The Color/No Color decision can either make or break even a well-balanced composition by making the “look here” rules for the viewer too ambiguous or unclear. Reading the room can help pictures communicate cleanly.

BURDEN OF PROOF

Reverse Shadows (2015) Originally conceived in color, later converted to black and white. Luckily, it worked out, but, shooting this image anew, I would execute it in monochrome from start to finish. Every story has its own tonal rules.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE WORLD OF PHOTOGRAPHY’S EMBRACE OF COLOR, which now seems instinctual and absolute, is actually a very recent thing. The arrival of color film stock targeted to the amateur market barely reaches back to the 1920’s, and its use in periodicals and advertising didn’t truly begin to outdistance color illustration until well after World War II. Color in so-called “serious” or “art” photography existed on the margins until half-way through the 1960’s, when hues, like every other element of the contemporary scene, gloriously exploded, creating a demand for color from everyone, amateur to pro. The ’60’s was also the first decade in which color film sales among snapshooters surpassed those of black and white.

Today, color indeed seems the default choice for the vast majority of shooters, with the “re-emergence” or “comeback” of black and white listed among each year’s top photo trend predictions. The ability to instantly retro-fit color images as monochrome (either in-camera or in-computer), has allowed nearly anyone to at least dabble in black & white, and the tidal wave of phone apps has made converting a picture to b&w an easy impulse to indulge.

And yet we seem to be constantly surprised that black & white has a purpose beyond momentary nostalgia or a “classic look”. We act as if monochrome is simply the absence of color, even though we see evidence every day that b/w has its own visual vocabulary, its own unique way of helping us convey or dramatize information. Long gone are the days when photographers regarded mono as authentic and color as a garish or vulgar over-statement. And maybe that means that we have to re-acquaint ourselves with b&w as a deliberate choice.

Certainly there has been amazing work created when a color shot was successfully edited as a mono shot, but I think it’s worth teaching one’s self to conceptualize b&w shots from the shot, intentionally as black and white, learning about its tonal relationships and how they add dimension or impact in a way separate from, but not better than, color. Rather than consistently shooting a master in color and then, later, making a mono copy, I think we need to evaluate, and plan, every shot based on what that shot needs.

Sometimes that will mean shooting black and white, period, with no color equivalent. Every photograph carries its own burden of proof. Only by choosing all the elements a picture requires, from color scheme to exposure basics, can we say we are intentionally making our images.