AN EFFECT IN SEARCH OF A MOTIVE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY HAS NEVER BEEN SATISFIED to act as a mere recorder of, although it has certainly been used as a clinical instrument, charged with documenting the size and texture of things in the “real world”. And as useful as it has been, since its inception, in helping to identify, quantify, catalogue or certify things (think police mug shots or historic events or travel destinations), shooters have never been comfortable with using it just to measure or preserve. Just as painting is innately interpretative, making no real claim to verity, so too photographs are points of departure from what is real….real PLUS, if you like.

Lenses and processes, then, have always been developed to service both the accuracy of documentation and the fancy of imagination. Same tools, different uses. Sometimes we can shoot something a certain way before we know why we would want to even do it, sort of an effect in search of a motive. We can make the picture do this. But why would we? That is to say that no custom gimmick or look is appropriate for every shooting situation. We marvel at the technology that conveys a certain sensation; deciding if it serves the image at hand is another thing entirely.

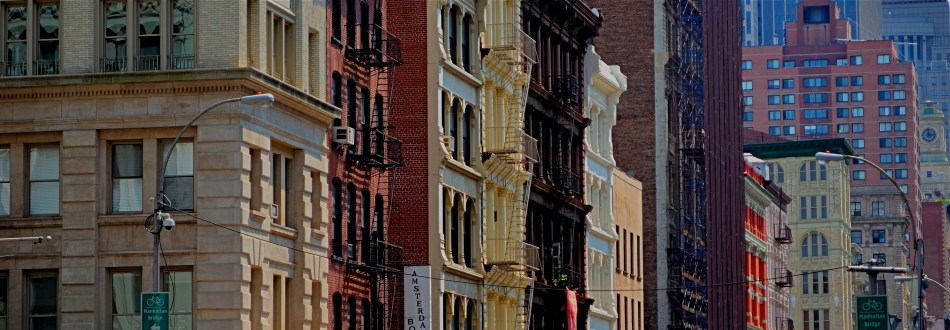

AS one example, an effect that began as an attempt to tell a more complete story is the panorama. Its beginnings were defined by specialized lenses and cameras that enabled chroniclers to show several thousand military cadets in one shot, or render the complete flow of an entire city block. Over the decades, dozens of techniques have been used to make panos easier to take, with digital tech making shooting them nearly instinctive. Still, the question for the photographer remains, what to do with this unique type of view? How to marry subject matter and system in such a way that both complement each other, rather than being merely novel? The making and processing of the shot seen here, for example, were all done in-camera with a cell phone and a cheap post-processing app, making it easy to follow a momentary impulse and have an acceptable result within minutes. But is anything unique said or amplified with this viewpoint? Is this the best way to display or portray this space? Was that the point?

Filtering reality through our own personal vision requires a unique match of gear and imagination. One cannot perform without the other, but the balance between the two is a delicate dance.

THE LONG AND SHORT OF IT

This original frame was just, um, all right, and I kept wanting to go back and find something more effective within it.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE INTRODUCTION OF THE FIRST PANORAMIC CAMERAS in the 1840’s can be seen as a freeing-up of the camera frame, a way to more accurately depict the entire field of view open to the human eye. And, of course that’s true. However, the first panos were also an early attempt by photographers to deliberately direct and orchestrate not only what you see, but how they want you to see it. Let’s concede that the western mind tends to absorb information in linear fashion. We read from left to right, we scan the horizon, and so forth. So making a photograph that instructs you to interpret horizontally is fairly natural.

So the first panos seem like a fairly modest extension of our visual bias. But think about the fundamental change that represented. Suddenly, photographers were saying, there are no rules except the rules I dictate. I decide what a frame is. I arrange not only the information inside the frame, but the frame itself. By re-shaping the box, I re-shape what you are to think about what’s in the box. That’s revolutionary, and today’s shooters would be wise to be mindful of that wonderful power.

I am fond of making what I will generously call “carved” panoramics, shots that began as standard framings but which I have cropped to force a feel of left-to-right linearity. Unlike standard panoramics, the shots were conceived and made with a very different compositional strategy, not necessarily trying to tell a horizontal story. However, on review, some stories-within-stories contain enough strong information to allow them to stand as new, tighter compositions in which the new instruction to the viewer’s eye is quite different from that in the original.

The full shot seen at the top of this page may or may not succeed as a typical “urban jungle” snap, in part because it contains both horizontal and vertical indices that can pull the eye all over the place. Since I wasn’t amazed by the shot itself, I decided to select a horizontal framing from its middle real estate that purposely directed the eye to laterally compare the facades of several different buildings stacked tightly down the street. Full disclosure: I also re-contrasted the shot to make the varying colors pop away from each other.

The result still may not be a world-beater, but the very act of cutting has re-directed the sight lines of the picture. For better or worse, I’ve changed the rules of engagement for the photograph. When such surgeries work, you at least fix the problem of extraneous clutter in your pictures, making them easier to read. Then it’s down to whether it was a good read or a beach read.

Hey, the box can’t fix everything.