STREAMING KILLED THE THEATRE STAR?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS YOU READ THIS, ANYONE WITH A KEYBOARD AND THE MINUTEST CONNECTION TO THE ENTERTAINMENT BIZ is crapping bricks over the sale of Warner Brothers to yet another new owner, (of which there have been more than a dozen), regarding said merger/sale as the death knell for theatrical movies in the Golden Age Of Streaming. This mass panic ignores the fact that “going to the movies”, as a regular practice, has been heading for Dodo-land for decades, and that, sorry folks, but things change and evolve. We will always love storytelling, but we will constantly be revising the delivery system we choose to use. Ask the 1920’s studio heads that predicted that “talkies” were a passing fad.

For me, the major sensory delight of going out to a film has been gone for some time, being intertwined as it was with the atmosphere engineered into the theaters built in the first third of the 1900’s. The over-the-top grandiloquence, the overkill raised to a the status of a science, immersed the moviegoer in rich fantasy worlds that provided vivid escape even before the curtain went up (yes, Virginia, there were curtains) and the overture began (and, yes, Virginia, there were overtures, as well). We had a deep, profound crush on the places where movies were shown, a crush that was trampled underfoot in the back half of the twentieth century, as those miraculous movie palaces were replaced with bland boxes, mere assembly halls equipped with projectors. They were certainly places we went to see movies, but they ceased to be…. theaters.

I live near Los Angeles now, and being a frequent day-trip visitor, I have inherited a plethora of dozens of grand old movie houses that, in the town that perfected make-believe, have been allowed to age into the 2000’s, repurposed either as subdivided multi-screen complexes, playhouses, or live performance venues. It’s the kind of legacy that has long since vanished from much of the heartland, and, as a photographer, I get a little drunk with power at the chance to walk their halls and document their dreamscapes. The images here are from a medium-sized 1930 cinema called the Saban, which hosts any and every kind of entertainment event at its original location on Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills. I love movies, and I always will. I also used to love where I went to love movies. Now, late in the game, I have more chances than ever to leaf through the scrapbook of that romance. Mergers be damned, it really wasn’t streaming that killed the theatre star; that particular murder has a hundred different authors.

I WAS JUST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD ANYWAY…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CROOKS AREN’T THE ONLY PEOPLE WHO RETURN TO THE SCENE OF THE CRIME. Photographers have the same neurotic habit of going back to the place where things went wrong. Only, instead of a “crime”, it’s the scene of a picture that we (a) loused up the first time (b) loused up the second time, (c) might look better with a different camera/exposure/lens or (d) is just some infernal, unsatisfiable itch that we must scratch or go crazy.

This building is one such place. I don’t know why it is filed in my fevered brain under “unfinished business”, but it is.

This apartment block is just one street away from the home of a dear friend in central Los Angeles, so I have probably made the short pilgrimage to it for at at least ten years’ worth of visits. Part of its attraction is that it’s one of the only original Art Deco structures left in the neighborhood. Another part of it is the utter simplicity of its design, as is its clean teal tone. I’ve been snapping it for so long now that a complete folder of my collected shots of it could easily serve as a time-line on my own development as a photographer, as I’ve taken a crack at it through every phase, fad and infatuation I’ve endured over those ten years.

I’ve taken it with wide-angles and telephotos, primes manual lenses and fully automatic exposure. I’ve given it the lo-fi treatment with both cheap plastic and pricey Lensbaby art lenses. I’ve done full-on frontal shots of the entire building, distorted fisheye angles from the corners and sides, time exposures just after sunset with its windows all aglow and, as seen here as vertical slices designed to abstract it to pure shape. I think I’m done. However, I’ve said that many times before.

It’s frustrating enough to get a single pass at a place or subject, such as a snap of a tourist location you’ll never re-visit. It’s frustrating in a different way to have unlimited access to something that you can’t quite seem to nail, not matter how many swings you take. I was not blessed with a natural bent toward humility. However, thanks to photography, it’s closer to second nature for me. If I live long enough, I might just finish growing up. Or finally get The Picture of this wretched building.

THE FOUR SISTERS

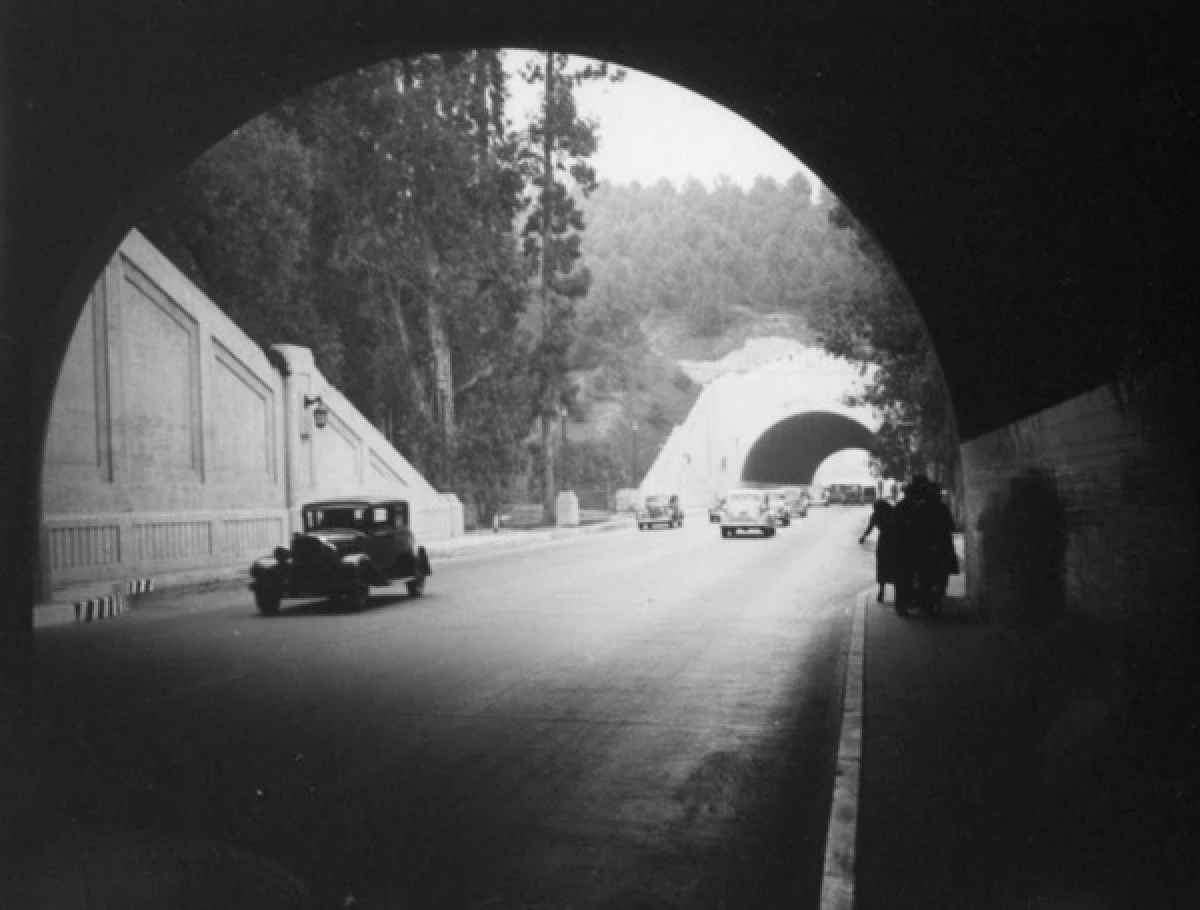

The Figueroa Tunnels connecting L.A. and Pasadena, soon after their opening in the 1930’s.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOS ANGELES IS CONSTANTLY IN THE ACT of obliterating its past; a term like “Old L.A” applies as much to a 1985 Blockbuster Video as a 1926 bank building in a town that, like the movie industry it hosts, tends to frequently “strike the set” and start again from scratch on a nearly daily basis. That’s why, for photographers (especially newly-arrived ones) finding infrastructure that is older than your family dog can be a touch task. Recently, however, I got my first look at such a fabled structure by merely driving up to it. And through it. Or through them.

The view through one of the four tunnels to its neighbor, along with local traffic signage, July 2025.

The first major highway linkages between downtown Los Angeles and nearby Pasadena were hard-won affairs, as the rugged hills of Elysian Park blocked the city’s Figueroa Street from direct entry to the smaller town, forcing north-south traffic to cross a bridge over the Los Angeles river, creating huge daily bottlenecks. And as was the usual case with many physical obstacles in the 20th century, it seemed like a “dynamite” idea to simply blast a roadway through the hills, not for just one tunnel, but for four. Engineer Merrill Butler, who also designed many other landmark crossings and tunnels throughout greater L.A., cranked out the first three of these beauties beginning in 1931, with a fourth, the longest at 755 feet, arriving after 1936 as yet one more way to direct and relieve traffic flow. Each was a gentle Deco arch design with streamlined support wings, custom “coach lights” and, at the keystone of each, an abstract sculpture of the Los Angeles city seal.

The shot you see here is a true snapshot, in that, not having motored through Pasadena for a long spell, I had completely forgotten that the tunnels were a feature of the last leg into town. Before I could reach any of my formal gear, we’d already entered the first tunnel, and so I managed to grab images of the proceeding three with my iPhone, anticipating the extremely wide lens default of the camera by waiting almost until entry to attempt to fill the shot with just the structure and very little of the surrounding sky, roadside and terrain. I love my first glimpses of sites in L.A. that were once fundamental to the growth of the city (the Arroyo Seco Parkway, built after the tunnels opened, actually does the heavy lifting on local traffic flow now) and have, almost by chance, been allowed to hang around and age into venerability. The camera’s function as time-traveler cum time-freezer is magical, and I value the gifts it yields.

THE ELEGANCE OF THE INVISIBLE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE DECORATIVE ARTS SHARE A COMMON MISSION, which is to elevate the ordinary by re-imagining it, transforming things from invisible to elegant. Sometimes, of course, a sow’s ear cannot become a silk purse, no matter how much you fiddle with it, and not everything in the everyday can be glorified by the touch of a designer or shooter. Still, both disciplines can, often, confer some kind of absolute beauty on objects that we’ve been largely conditioned to ignore.

One of my favorite marriages of decorative arts and photography can be seen in the brief reign of what we now call Art Deco, although that term was coined decades after the movement sort of, well, moved on. Less extreme in its flowery ornamentation than its ancestor Art Nouveau, Deco gaily celebrated the furnishings of our daily lives, from parquet floors to wastebaskets to skyscrapers, making them some of the first industrially designed mass-produced objects of the Machine Age. meanwhile transforming consumption in the 1920’s and 30’s. At the same time, Photography was having its first Great Awakening, moving from a mere recording medium to an art form, one which, like Deco-designed works, could suddenly be copied and re-copied endlessly via film and print. The making of images that celebrated the ordinary as well as the extraordinary made for a unique amalgam of style and expression.

Just one look at a simple, typically invisible thing like a public mail drop box from the period (this one in daily use at the Hotel del Coronado in San Diego as of this writing) reveals a love of symmetry, of clean, budgeted lines, and a minimalist aesthetic that is about how a thing strikes you visually much more than what its actual function might be. Photographs can not only serve to capture these works before they vanish, but to do for them what they did for our most “normal” tasks, and that is to glorify them. Art Deco and photography have proven, over time, to be one of the happier marriages in the arts. And like all the best lovers, they never let the honeymoon end.

STUBBORNS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE BEST OF YOUR PHOTOGRAPHS HAVE A KIND OF INEVITABILITY TO THEM, as if they were always destined to be made. Once they are finally captured, they also seem always to have existed, somehow. This is due, in part, to the fact that many of them had to fight hard to be born. That is, something about their conception or execution kept getting stuck in the pipe, try after try, until a tremendous amount of patience and work made them seem almost accidental or effortless.

I call these shots stubborns because I can almost feel them refusing to be taken, haunting me for months or even years until I can get a final take that does what I see in my head. The stubborns list contains a few that actually were tamed and brought to heel, but it’s mostly an agonizing roster of images that I have yet to nail down. Maybe the idea’s not fully formed. Maybe there’s something geographically blocking me, like a location I can’t readily get back to for a re-take. Sometimes I just haven’t brought the idea to its final, best form, unable to generate anything but near misses.

Ever since I first saw this wondrous entrance to the Hollywood Bowl, George Stanley’s Muses of Music, Dance, & Drama, I have dreamed of making “the” image of it. The enormous slab of concrete, which is faced by over two-hundred and forty-five tons of granite, depicts one sitting figure and two smaller standing figures (not visible in this shot) at its left and right flank. It is the biggest WPA-New Deal-era sculpture project in all of California, completed in 1940. Beyond the sheer beauty and enormity of the thing is that fact that, to do a proper job of interpreting it, you’d have to have time to roam around the site and shoot dozens of variously wrong versions over a number of hours, then decide whether it’s more stunning by daylight or lit on concert nights.

As fate and circumstance would have it, my access to it over the space of seven years and at least fifteen visits to the Los Angeles area has been limited to this passenger-seat drive-by (okay, we were paused at a light for ten whole seconds) from 2015, shot through a smudgy window on an iPhone 5S. Ideal conditions this ain’t, and as of 2022 I am still unsure when I will manage to get onto the Bowl property to do the ladies justice. Stubborn, indeed.

My point is that the best photographs are generated in stages, or drafts, if you like. True, some masterpieces come into the world on the first click, but even those lucky winners might be improved if time and care drill down to a second, more foundational truth.

A SYMPHONY IN AQUAMARINE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A DRIVE DOWN OCEAN AVENUE IN SANTA MONICA, CALIFORNIA, directly opposite the town’s fabled Pacific Park (and that glorious neon pier entrance), is usually a slow and stately one, given the nonstop traffic along the city’s main artery, which is itself a major link to the Pacific Coast Highway. The streets are regularly clogged with visitors, a given in a city that, only a hundred years ago, was a sleepy bedroom community far enough away from Hollywood Proper to be thought of as an exclusive (and slightly shady) getaway for the rich and famous.

The Georgian Hotel, Santa Monica, California, July 3, 2021

One of SM’s most venerable architectural citizens is the gloriously Deco-rative Georgian Hotel, which, during the waning days of Prohibition, gained notoriety as a glamorous go-to for those seeking a little under-the-table taste. In the California of the late 1920’s, Santa Monica was still not long past its days as a tiny Chinese-Japanese fishing village, with the site of the hotel surrounded by a small forest, and….not much else. The Georgian’s formal 1933 opening coincided with the return of legal liquor, which confirmed its status as a chic retreat for the film community, with the likes of Clark Gable and Carole Lombard enjoying the ocean views alongside occasional clandestine stays from Al Capone and Bugsy Siegel. The hotel came to be the visual signature of the town’s full entry into the 20th century, and of the non-stop westward sprawl from L.A. that would continue to transform the waterfront for decades to come. By 2000, this elegant symphony in aquamarine attained monument status, and underwent a multi-million dollar restoration, guaranteeing its survival to the present day.

Photographing what I call a First-Tier-Postcard attraction, a place that everyone feels they simply must check off their bucket lists, doesn’t often result in anything new being done, beyond merely recording one’s “take” of it. In some ways, famous places are the most challenging things to shoot, since you’re in competition with the entire world in your desire to say something personal or unique. But, as this summer marks almost twenty years since the last time I photographed the Georgian, I recently approached the task with as much “just do it” zen energy as possible. It continues to delight and fascinate me with its quiet elegance, and its ability to evoke a world that has largely vanished, even as it’s been joined by other brighter, brassier neighbors over the years. Sometimes it’s just a privilege to be standing where so much magic has happened, and to take comfort that, to a degree, some of the old spell persists.

THE MAN IN THE ROUND CUBE

NOTHING IS SO TIMELESS as something whose time has come and gone.

Once a thing… a style, a design element, a fashion, an idea…has outlasted its original context, becoming truly out of sync with the world, it can become visually fascinating to the photographer. Instead of forward-looking, it’s dubbed “retro”. Rather than radical, it becomes something no one can ever remember having been excited about, like looking at Carol Brady’s shag haircut 25 years on.m

The information booth in the frame shown here is one such anomaly, so odd a fit in the building that it’s part of (the California state capitol annex) that it wrenched my attention away from a pretty good tour. The wing the booth is part of, built from 1949 to 1952, is, generously speaking, as dull as dishwater, indistinguishable from most generic government buildings, a box of sugar cubes.

But the booths are something else again.

Far from the typical marble-block, cage-and-window, bank teller enclosure many public servants call home, the booth is curved wood and glass, sounding a faint echo of Art Deco which extends even to the aluminum letters that spell out INFORMATION. And yet, at present, the modernity of the original design is now itself antique, its lonely occupant looking as if he were banished to his post rather than assigned.

The lighting within the booth is so minimal that the poor man’s features are nearly swallowed in deepening shadow: he looks like a recreation in some museum diorama about What Offices Will Look Like In The Future!!!, as strange to view as “modern” renderings of someday space rockets as seen from 1950. And then there’s the insect-repellant visor green on half of the glass, which is there, I assume, to protect Mr. Info from harsh gamma rays(??). The entire effect is one of loneliness, of, again, the evidence of a time (or a man) whose time has come and gone. And that calls, in my world, for a picture.

INVISIBLE CITIES

New York is one of the great treasure troves for lovers of Art Deco. This complex, along Lexington Avenue, is literally in the shadow of the Chrysler building.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS, IN THE WORLD OF SPORTS, A PSYCHOLOGICAL EDGE known as the “home field advantage”, wherein a team can turn a superior knowledge of its native turf against its visiting opponent. The accuracy of this belief has never been conclusively proven, but it’s interesting to think on whether it applies to photography as well. Do we, for the purposes of making pictures, know our own local bailiwicks better than visitors ever can? Or is it, as I suspect, the dead opposite?

Familiarity may not breed contempt, but, when it comes to our seeing everything in our native surroundings with an artistic eye, it can breed a kind of invisibility, a failing to see something that has long since receded into the back part of our attention, and thus stops registering as something to see anew, or with fresh interpretation. How many buildings on the street we take into the office are still standouts in our mind’s eye? How many objects would we be amazed to learn are actually part of our walk home, and yet “unseen” by us as we mentally drift along that drab journey?

It may be that there is actually a decided “out-of-towner” advantage in visiting a place where you have no pre-conceptions or habitual routes, in approaching things and places in cities as totally new, free of prior associations. I’ve often been asked of an image, “where did you take that?” only to inform the questioner that the building in the picture is a half block from their place of business. The above image was taken on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, not more than a half block and across the street from the Chrysler building. It is a gorgeous treasure of design cues every bit as symbolic of the golden age of Art Deco as its aluminum clad neighbor, and yet I could hold a contest amongst many New Yorkers as to where or what it is and never have to award the prize money. The Chrysler’s very fame eclipses its neighbors, rendering them less visible.

Perception is at the heart of every visual art, and the most difficult things to re-imagine are the ones which have ceased to strike us as special. And since everyone lives in a city that is at least partly invisible to them, it stands to reason that an outside eye can make its own “something new” out of everyone else’s “something old”. Realize and celebrate your special power as a photographic outlier.

25, 50, T, B

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A PART OF WILSHIRE BOULEVARD IN LOS ANGELES that I have been using for a photographic hunting ground for over ten years, mostly on foot, and always in search of the numerous Art Deco remnants that remain in the details of doors, window framings, neighborhood theatres and public art. Over the years, I have made what I consider to be a pretty thorough search of the stretch between Fairfax and LaBrea for the pieces of that streamlined era between the world wars, and so it was pretty stunning to realize that I had been repeatedly walking within mere feet of one of the grand icons of that time, busily looking to photograph….well, almost anything else.

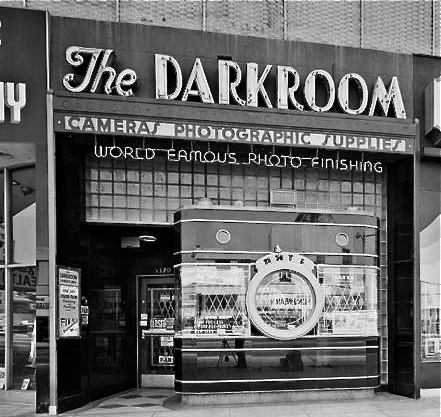

A few days ago, I was sizing up a couple framed in the open window of a street cafe when my composition caught just a glimpse of black glass, ribbed by horizontal chrome bands. It took me several ??!?!-type minutes to realize that what I had accidentally included in the frame was the left edge of the most celebrated camera in all of Los Angeles.

Opened in the 1930’s, the Darkroom camera shop stood for decades at 5370 Wilshire as one of the greatest examples of “programmatic architecture”, that cartoony movement that created businesses that incorporated their main product into the very structure of their shops, from the Brown Derby restaurant to the Donut Hole to, well, a camera store with a nine-foot tall recreation of an Argus camera as its front facade.

The surface of the camera is made of the bygone process known as Vitrolite, a shiny, black, opaque mix of vitreous marble and glass, which reflects the myriad colors of Los Angeles street life just as vividly today as it did during the New Deal. The shop’s central window is still the lens of the camera, marked for the shutter speeds of 1/25th and 1/50th of a second, as well as T (time exposure) and B (bulb). A “picture frame” viewfinder and two film transit knobs adorn the top of the camera, which is lodged in a wall of glass block. Over the years, the store’s original sign was removed, and now resides at the Museum of Neon Art in Glendale, California, while the innards of the shop became a series of restaurants with exotic names like Sher-e-Punjab Cuisine and La Boca del Conga Room. Life goes on.

True to the ethos of L.A. fakes, fakes of fakes, and recreations of fake fakes, the faux camera of The Darkroom has been reproduced in Disney theme parks in Paris and Orlando, serving as…what else?….a camera shop for visiting tourists, while the remnants of the original storefront enjoy protection as a Los Angeles historic cultural monument. And, while my finding this little treasure was not quite the discovery of the Holy Grail, it certainly was like finding the production assistant to the stunt double for the stand-in for the Holy Grail.

Hooray for Hollywood.

A BLOCK OF THE MILE

The building that originally housed Desmond’s department store, and one of the mostly intact survivors of a golden age of Art Deco along Los Angeles’ historic “Miracle Mile”.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CALIFORNIA’S CITIES, FOR STUDENTS OF DESIGN, contain the country’s largest trove of Art Deco, the strange mixture of product packaging, graphics, and architectural ornamentation that left its mark on most urban centers in America between 1927 and the beginning of World War II. The Golden State seems to have a higher concentration of the swirls, chevrons, zigzags and streamlined curves than many of the country’s “fly over” areas, and the urban core of Los Angeles is something like a garden of delights for Deco-dent fans, with stylistic flourishes preserved in both complete buildings and fragmented trim accents on business centers that have been re-purposed, blighted, re-discovered, resurrected or just plain neglected as the 20th century became the 21st. And within that city’s core (stay with me) the up-again-down-again district once dubbed the “Miracle Mile”, centered along Wilshire Boulevard, remains a bounteous feast of Deco splendor (or squalor, depending on your viewpoint).

CALIFORNIA’S CITIES, FOR STUDENTS OF DESIGN, contain the country’s largest trove of Art Deco, the strange mixture of product packaging, graphics, and architectural ornamentation that left its mark on most urban centers in America between 1927 and the beginning of World War II. The Golden State seems to have a higher concentration of the swirls, chevrons, zigzags and streamlined curves than many of the country’s “fly over” areas, and the urban core of Los Angeles is something like a garden of delights for Deco-dent fans, with stylistic flourishes preserved in both complete buildings and fragmented trim accents on business centers that have been re-purposed, blighted, re-discovered, resurrected or just plain neglected as the 20th century became the 21st. And within that city’s core (stay with me) the up-again-down-again district once dubbed the “Miracle Mile”, centered along Wilshire Boulevard, remains a bounteous feast of Deco splendor (or squalor, depending on your viewpoint).

The Miracle Mile was born out of the visionary schemes of developer A. W. Ross, who, in the 1920’s, dreamed of drawing retail dollars to an area covered in farm fields and connected only tentatively to downtown L.A. by the old “red car” trolley line and the first privately owned automobiles. Ignoring dire warnings that the creation of a massive new business district in what was considered the boondocks was financial suicide, Ross pressed ahead, and, in fact, became one of the first major developers in the area to design his project for the needs of passing car traffic. Building features, display windows, lines of sight and signage were all crafted to appeal to an auto going down the streets at about thirty miles per hour. As a matter of pure coincidence, the Mile’s businesses, banks, restaurants and attractions were also all being built just as the Art Deco movement was in its ascendancy, resulting in a dense concentration of that style in the space of just a few square miles.

The period-perfect marquee for the legendary El Rey Theatre, formerly a movie house and now a live-performance venue.

It was my interest in vintage theatres from the period that made the historic El Rey movie house, near the corner of Wilshire and Dunsmuir Avenue, my first major discovery in the area. With its curlicue neon marquee, colorful vestibule flooring and chromed ticket booth, the El Rey is a fairly intact survivor of the era, having made the transition from movie house to live-performance venue. And, as with most buildings in the neighborhood, photographs of it can be made which smooth over the wrinkles and crinkles of age to present an idealized view of the Mile as it was.

But that’s only the beginning.

On the same block, directly across the street, is another nearly complete reminder of the Mile’s majesty, where, at 5514 Wilshire, the stylish Desmond’s department store rose in 1929 as a central tower flanked by two rounded wings, each featuring enormous showcase windows. With its molded concrete columns (which resemble abstract drawn draperies), its elaborate street-entrance friezes and grilles, and the waves and zigzags that cap its upper features, the Desmond had endured the Mile’s post 1950’s decline and worse, surviving to the present day as host to a Fed Ex store and a few scattered leases. At this writing, a new owner has announced plans to re-create the complex’s glory as a luxury apartment building.

The details found in various other images in this post are also from the same one-block radius of the Wilshire portion of the Mile. Some of them frame retail stores that bear little connection to their original purpose. All serve as survivor scars of an urban district that is on the bounce in recent years, as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (installed in a former bank building), the La Brea Tar Pits, and other attractions along the Mile, now dubbed “Museum Row”, have brought in a new age of enhanced land value, higher rents and business restarts to the area. Everything old is new again.

The Wilshire Boulevard entrance to Desmond’s, with its period friezes, ornate grillwork and curved showcases intact.

Ironically, the district that A.W. Ross designed for viewing from behind the wheel of a car now rewards the eye of the urban walker, as the neighborhoods of the Miracle Mile come alive with commerce and are brought back to life as a true pedestrian landscape. Walk a block or two of the Mile if you get a chance. The ghosts are leaving, and in their place you can hear a beating heart.

Suggested reading: DECO LAndmarks: Art Deco Gems of Los Angeles, by Arnold Schwartzman, Chronicle Books, 2005.

Suggested video link: Desmond’s Department Store http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJj3vxAqPtA

BIG STORY, LITTLE STORY

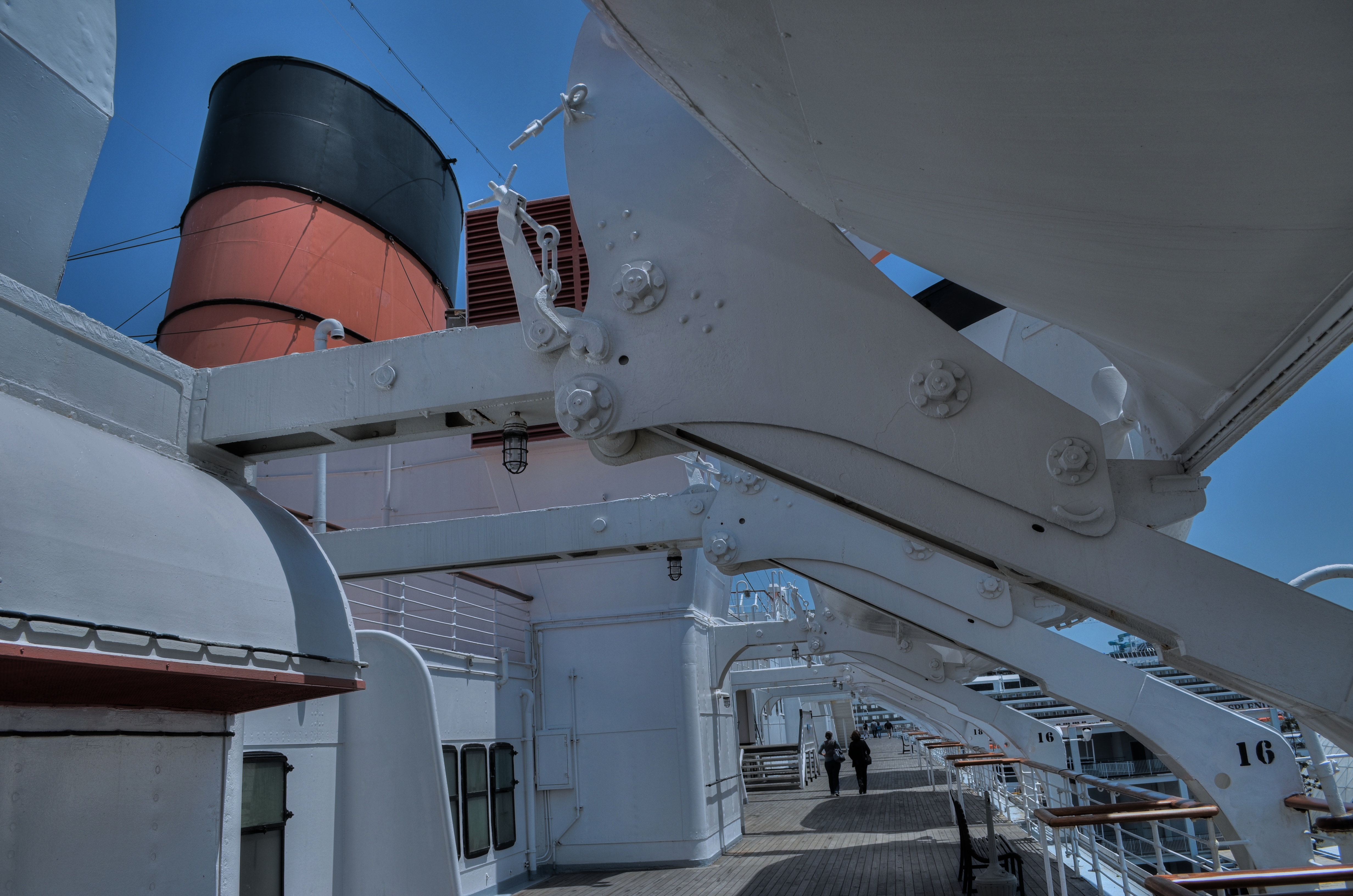

Which image better conveys the romantic era of the Queen Mary, the wide-angle shot along the promenade deck (above), or a detail of lights and fixtures within one of the ship’s shops (below)?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE VERY APPEAL THAT ATTRACTS HORDES OF VISITORS to travel destinations around the world, sites that are photographed endlessly by visitors and pilgrims alike, may be the same thing that ensures that most of the resulting images will be startlingly similar, if not numbingly average. After all, if we are all going for the same Kodak moment, few of us will find much new truth to either the left or right of a somewhat mediocre median.

In a general sense, yes, we all have “access” to the Statue of Liberty, the Grand Canyon, Niagara Falls, etc., but it is an access to which we are carefully channeled, herded, and roped by the keepers of these treasures. And if art is a constant search for a new view on a familiar subject, travel attractions provide a tightly guarded keyhole through which only a narrowly proscribed vantage point is visible. The very things we have preserved are in turn protected from us in a way that keeps us from telling our subject’s “big story”, to apprehend a total sense of the tower, temple, cathedral or forest we yearn to re-interpret.

More and more, a visit to a cultural keepsake means settling….for the rooms you’re allowed to see, the areas where the tours go, the parts of the building that have been restored. Beyond that, either be a photographer for National Geographic, or help yourself to a souvenir album in our gift shop, thank you for your interest. Artistically speaking, shooters have more latitude in capturing the stuff nobody cares about; if a locale is neglected or undiscovered, you have a shot at getting the shot. Imagine being Ansel Adams in the Yosemite of the 1920’s, tramping around at will, decades before the installation of comfort stations and guard rails, where his imagination was only limited by where his legs could carry him (and his enormous and unwieldy view camera, I know). Sadly, once a site has been “saved”, or more precisely, monetized, the views, the access, the original feel of its “big story” is buried in theme cafes, commemorative shrines, info counters, and, not insignificantly, competition with every other ambitious shooter, who, like you, wants a crack at whatever essences can still be seen between the trinkets and kiosks.

On a recent visit to the 1930’s luxury liner RMS Queen Mary, in Long Beach, California, I tried with mixed results to get a true sense of scale for this Art Deco leviathan, but its current use as a hotel, tour trek and retail mall has so altered the overall visual flow that in some cases only “small stories” can effectively be told. Steamlined details and period motifs can render a kind of feel for what the QM might have been before its life as a kind of ossified merchandise museum, but, whereas time has not been able to rob the ship’s beauty, commerce certainly nibbles around its edges.

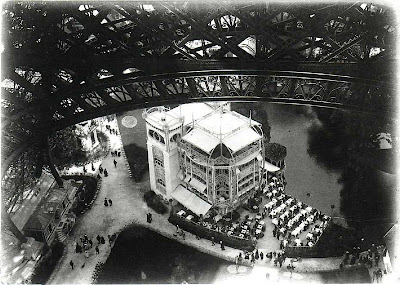

Sometimes you win the game. I recently discovered the above snapshot of the Eiffel Tower, taken in 1900 by the French novelist Emile Zola, where real magic is at work. Instead of clicking off the standard post card view of the site, Zola climbed to the tower’s first floor staircase, then shot straight down to capture an elegant period restaurant situated below the tower’s enormous foundation arches. And although only a small part of the Eiffel is in his final frame, it is contextualized in size and space against the delicate details of tables, chairs, and diners gathered below, glorifying both the tower and the bygone flavor of Paris at the turn of the 20th century.

Perhaps, for a well-recorded destination, the devil (and the delight) is in the details. Maybe we should all be framing tighter, zooming in, looking for the visual punctuation instead of the whole paragraph. Maybe all the “little stories” add up to a sum greater than that of the almighty master shot we originally went after. Despite the obstacles, we must still try to dictate the terms of engagement.

One image at a time.

Thoughts?