JUST ENOUGH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE PROBABLY SCRIBBLED MORE WORDS, IN THESE PAGES, ABOUT OVERCROWDED SHOTS than about any other single photographic topic, so if I sound like I’m testifyin’ in the Church-Of-I-Have-Seen-The-Light, bear with me. If any single thing has been a common theme in the last five years of my photography (or a factor in my negligible growth), it’s been the quest to take pictures that tell just enough, then back off before they become cluttered with excess visual junk.

Composing a photograph, when we start out as young budding photogs, seems to be about getting everything possible into the frame. All your friends. All the mountains and trees. Oh, and that cute dog that walked by. And, hey, those clouds, aren’t they something? Then, as we grow grayer of beard and thinner of scalp, the dead opposite seems to be true. We begin looking for things to throw away in the picture. Extra visual detours and distractions that we can pare away and, not only still have a picture, but, ironically, have more of a picture, the less we include. It’s very Zen. Or Buddhist. Or Zen Buddhist. Or something. Hey, I ain’t Depak Chopra. I just get a smidge better, as I age, at not making every image into a Where’s Waldo tapestry.

Especially in an age of visual overload, it’s too easy to make photographs that make your eye wander like a nomad all over the frame, unsure of where to land, of what to fix upon. Unable to detect the central story of the shot. Professionals learn this before any of the rest of us, since they often have to submit their work to editors or other unfeeling strangers outside their family who will tell them where their photos track on the Suck-O-Meter. There’s nothing like having someone that you have to listen to crumple up about 90% of your “masterpieces” and bounce them off your nose. Humility the hard way, and then some. But, even without a cruel dictator screaming in your ear that you ought to abandon photography and take up sewer repair, you can train yourself to take the scissors to a lot of your photos, and thereby improve them.

The image up top began with the truck occupying just part of what I hoped would be a balanced composition, showing it in the context of a western desert scene. Only the truck is far more interesting a subject than anything else in the image, so I cropped until the it filled the entire frame. Even then, the grille of the truck was worthy of more attention than the complete vehicle, so I cut the image in half a second time, squaring off the final result and shoving the best part of the subject right up front.

The picture uses its space better now, and, strong subject or weak, at least there is no ambiguity on where you’re supposed to look. Sometimes that’s enough. That’s Zen, too.

I think.

PLEASE PLAY WITH YOUR FOOD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC STILL-LIFES ARE THE POOR MAN’S PRACTICE LAB. All the necessary elements for self-taught imaging are plentiful, nearby, and generally cheap. As has been demonstrated perpetually across the history of photography, the subjects themselves are only of secondary importance. What’s being practiced are the twin arts of exposure and composition, so it doesn’t matter a pig whistle whether you’re assembling a basket of oranges or throwing together a pile of old broken Barbie dolls. It’s not about depicting a thing so much as it is about finding new ways to see a thing.

That’s why an entire class of shooters can cluster around the same randomly chosen subject and produce vastly different viewing experiences. And why one of the most commonly “seen” things in our world, for example, food, can become so intriguingly alien when subjected to the photographer’s eye.

Shooting food for still-life purposes provides remarkably different results from the professional shots taken to illustrate articles and cookbooks. “Recipe” shots are really a way of documenting what your cooking result should resemble. But other still-life shots with food quickly become a quest to show something as no one else has ever shown it. It’s not a record of a cabbage; it’s a record of what you thought about a cabbage on a given day.

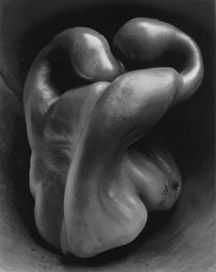

Many books over the years have re-printed Edward Weston’s famous black-and-white shots of peppers, in which some people “saw” things ranging from mountain terrain to abstract nudes. These remarkable shots are famous not for what they show, but for what they make it possible to see. Food’s various signature textures, under the photographer’s hand, suggest an infinite number of mental associations, once you visually unchain the source materials from the most common perception of their features.

As the head chef around my house, I often pick certain cooking days where I will factor in extra time, beyond what it takes to actually prepare whatever meal I’m planning. That additional time is reserved so I can throw food elements that interest me into patterns…..on plates, towels, counters, whatever, in an effort to answer the eternal photog question, is this anything? If it is, I snap it. If it’s not, I eat it (destroying the evidence, as it were).

Either way, I get what I call “seeing practice”, and, someday, when a rutabaga starts to look like a ballerina, I might be ready. Or maybe I should just lie down until the feeling passes.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- Is Food Art: Notes from a Food Photographer (okramagazine.org)

AFTER-IMAGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WITHOUT GETTING TOO OVERLY OOKY-SPOOKY, I believe that photographers are witnesses to, well, ghosts. Specializing in the visualization of what might be (as near as our next frame), we are also retro-witnesses, or mediums, if you will, using found objects to call back the spirit of things that are no longer here. “If these walls could talk”, we instinctively remark as we walk into Notre Dame, Independence Hall, or Ellis Island, and yet, we think we are merely being poetic when we utter that phrase.

Are we?

Objects give up their secrets slowly, and in these posts I have often gone back to my fond desire to resurrect at least the essence of the owners of those objects, re-capturing people in the things they held, kept, cherished, wore to pieces, loved to death. We use every atom of our imagination trying to inch forward toward some revelation yet-to-be….a way to will a picture into being. But we are surprised to find ourself also trying to conjure forth echoes. And yet some of the most moving portraits we can produce show no people at all. I’m sure you have found this to be true.

For reasons I don’t quite understand, chairs resonate especially for me. They’re personal. They’re social. Deals are struck in them; stories are told, babies are soothed, pauses are taken, contemplation occurs. Lives pass.

For you, it might be other things that are left behind, but still ringing with the echoes of people. Books. Clothing. Cars. They can be anything, but whatever their strange stories, you can often hear them, and that makes them far from “empty”. Cameras record everything that can be seen and lots of things that can only be sensed. They may be only machines, but in the hands of dreamers they are divining rods.

Your houses are haunted, and in a good way.

Call the spirits forth.

Related articles

- Between objects and life (thehindu.com)

PERISHABLE

Once upon a time there was a very old apple. Shot real wide and in tight to suck up as much window light as possible and bend the shape a little. 1/50 sec., f/3.5, ISO 160, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I‘M ALMOST TO THE POINT WHERE I DON’T WANT TO THROW ANYTHING AWAY. I’ve written here before about pausing just a beat before chucking out what, on first glance, appears to simply be junk, hoping that a second look will tell me if this rejected thing has any potential as a still life subject. I realize that this admission on my part may conjure images of a pathetic old hoarder whose apartment is packed with swaying columns of yellowed newspapers from 1976 and pizza boxes that have become filing cabinets for old soda bottles, mismatched hardware, and souvenir tickets from Elvis’ last concert.

It’s not that bad.

Yet.

For this I have my wife to thank, since the civilizing influence she brings to my life tends to bank the freakier fires of my aesthetic wanderings. Still, there are hours each day when she’s at work, heh heh, hours during which the mad scavenger rescues the odd object, deluding himself that it is the next big thing in artsy coolness.

That’s what led me to the apple. Actually, I was rooting around in the garage fridge for a beer. The “backup” fridge often acts as a kind of museum of the lost for things we meant to finish eating or bring into the house. The abandoned final four strands of ziti from the restaurant. The sad survivors from the lunch we packed for the office, then left behind since we were running late.

And, in this case, a very old apple.

Having seen gazillions of pieces of fruit frozen in time by photographers, I am sometimes more interested in preserving the moment when Nature has decided to call them home. It’s not like decay is attractive per se, but seeing the instant where time is actually changing the terms of the game for an object, as it always is for us, can be oddly fixating.

So I set this old soldier on a slab and shot away for about a dozen frames. Window light, plain as mud, really zero technique. The colors on the apple were still bright, but the wrinkles had become furrows now, sucking up light and creating strange shadows. Something was leaving, collapsing, vanishing before my eyes, and I wanted to stop it, if only for a second.

And yes, in case you are asking, I did finally throw the thing away.

And got myself a beer.

BOXFULS OF HISTORY

Once, these objects were among the most important in our daily lives. Seen anew after becoming lost in time, they show a new truth to our eyes. 1/60 sec., f/4.5, ISO 100, 30mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE DAYS WHEN THERE IS NOTHING TO SHOOT, or so it seems. The “sexy” projects are all out of reach, the cool locales are too far away, or the familiar themes seem exhausted. Indolence makes the camera feels like it weighs thirty pounds, and, in our creative doldrums, just the thought of lifting it into service seems daunting. These dead spots in our vision can come between projects, or reflect our own short-sighted belief that all the great pictures have already been made. Why bother?

“Time is wasting”… but need not be wasted. Find the small stories of lost objects lurking in your junk drawers. 1/30 sec., f/2.8, ISO 200, 7.9mm.

And yet, in most people’s immediate circle of life there are literally boxfuls of history …..the debris of time, the residue of the daily routines we no longer observe. In Raiders Of The Lost Ark, the villain Rene Belloq makes the observation that everything can be an archaeological find:

Look at this pocket watch. It’s worthless. Ten dollars from a vendor in the street. But I take it, I bury it in the sand for a thousand years, and it becomes priceless.

Subjects ripe for still lifes abound in our junk drawers, in the mounds of memorabilia that our loving friends or spouses dreamily wish we would give to the Goodwill. Once ordinary, they have been made into curiosities by having been taken out of the timeline. In many ways, our camera is acting as we did when we first beheld them. And getting to see something familiar in a new way is photography’s greatest gift, a creative muscle we should all be seeking to flex.

Call it “seeing practice.”

Ordinary things are no longer ordinary once they are removed from daily use. Their context is lost and we are free to judge them as we cannot when they are part of the invisible fabric of daily habit. For example, how ordinary are those old piles of 45-rpm records on which we no longer drop a needle? Several revolutions in sound later, they no longer provide the same aural buzz they once did, and yet they still offer something special in the visual sense. The bright colors and bold designs that the record labels used to grab the attention of music-crazed teenagers in the youth-heavy ’60’s are now vanished in a world that first made all “records” into bland silver-colored CDs and then abolished the physical form of the record altogether. They are little billboards for the companies that packaged up our favorite hits; there is no “art” message on most of the sleeves, as there would have been on album covers. They are pure, unsentimental marketing, but the discs they contain are now a chronicle of who we were and what we thought was important, purchases which now, at the remove of half a century, allow us to make a picture, to interpret or re-learn something we once gave no thought to at all.

Old trading cards, obsolete clothing, trinkets, souvenirs, heirlooms….our houses are brimming with things to be looked at with a different eye. There is always a picture to be made somewhere in our lives. And that means that many of the things we thought of as gone are ready to be here, again, now. Present in the moment, as our eyes always need to be.

The idea of “re-purposing” was an everyday feat for photographers 150 years before recycling hit its stride. Everything our natural and mechanical eyes see is fit for a second, or third, or an infinite number of imaginings.

Your crib is bulging with stories.

All the tales need is a teller.

Thoughts?

BEYOND THE THING ITSELF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU NO DOUBT HAVE YOUR OWN “RULES” as to when a humble object becomes a noble one to the camera, that strange transference of energy from ordinary to compelling that allows an image to do more than record the thing itself. A million scattered fragments of daily life have been morphed into, if not art, something more than mundane, and it happens in an altogether mysterious way somewhere between picking it and clicking it. I don’t so much have a list of rules as I do a sequence of instincts. I know when I might have stumbled across something, something that, if poked, prodded or teased out in some way, might give me pleasure on the back end. It’s a little more advanced than a crap shoot and a far cry from science.

With still life subjects, unlike portraits or documentary work. there isn’t an argument about the ethics or “purity” of manipulating the material….rearranging it, changing the emphasis, tweaking the light. In fact, still lifes are the only kinds of pictures where “working it” is the main objective. You know you’re molding the material. You want to see what other qualities or aspects you can reveal by, well, kind of playing with your food. It’s like Richard Dreyfuss shaping mashed potatoes into the Devil’s Tower.

If I have any hard and fast rule about still lifes, it may be to throw out my trash a little slower. I can recall several instances in which I was on my way the garbage can with something, only to save it from oblivion at the last minute, turn it over on a table, and then try to tell myself something new about it from this angle or that. The above image, taken a few months ago, was such a salvage job, and, for reasons only important to myself, I like what resulted. Hey, Rauschenburg glued egg cartons on canvas. This ain’t new.

My wife had packed a quick fruit and nut snack into a piece of aluminum foil, forgot to eat it, and brought it back home in her lunch sack. In cleaning out the sack, I figured she would not want to take it a second day and started to throw it out. Re-wrapped several times, the foil now had a refractive quality which, in conjunction with window light from our patio, seemed to amp up the color of the apple slice and the almonds. Better yet, by playing with the crinkle factor of the foil, I could turn it into a combination reflector pan and bounce card. Five or six shots worth of work, and suddenly the afternoon seemed worthwhile.

I know, nuts.

Fruits and nuts, to be exact. Hey, if we don’t play, how will we learn to work? Get out on the playground. Make the playground.

And inspect your trash as you roll it to the curb.

Hey, you never know.

Thoughts?