PERISHABLE

Once upon a time there was a very old apple. Shot real wide and in tight to suck up as much window light as possible and bend the shape a little. 1/50 sec., f/3.5, ISO 160, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I‘M ALMOST TO THE POINT WHERE I DON’T WANT TO THROW ANYTHING AWAY. I’ve written here before about pausing just a beat before chucking out what, on first glance, appears to simply be junk, hoping that a second look will tell me if this rejected thing has any potential as a still life subject. I realize that this admission on my part may conjure images of a pathetic old hoarder whose apartment is packed with swaying columns of yellowed newspapers from 1976 and pizza boxes that have become filing cabinets for old soda bottles, mismatched hardware, and souvenir tickets from Elvis’ last concert.

It’s not that bad.

Yet.

For this I have my wife to thank, since the civilizing influence she brings to my life tends to bank the freakier fires of my aesthetic wanderings. Still, there are hours each day when she’s at work, heh heh, hours during which the mad scavenger rescues the odd object, deluding himself that it is the next big thing in artsy coolness.

That’s what led me to the apple. Actually, I was rooting around in the garage fridge for a beer. The “backup” fridge often acts as a kind of museum of the lost for things we meant to finish eating or bring into the house. The abandoned final four strands of ziti from the restaurant. The sad survivors from the lunch we packed for the office, then left behind since we were running late.

And, in this case, a very old apple.

Having seen gazillions of pieces of fruit frozen in time by photographers, I am sometimes more interested in preserving the moment when Nature has decided to call them home. It’s not like decay is attractive per se, but seeing the instant where time is actually changing the terms of the game for an object, as it always is for us, can be oddly fixating.

So I set this old soldier on a slab and shot away for about a dozen frames. Window light, plain as mud, really zero technique. The colors on the apple were still bright, but the wrinkles had become furrows now, sucking up light and creating strange shadows. Something was leaving, collapsing, vanishing before my eyes, and I wanted to stop it, if only for a second.

And yes, in case you are asking, I did finally throw the thing away.

And got myself a beer.

MAKE SOMETHING UP

Table-top romance gone wrong. Plastic Frank runs out on his clingy and equally plastic girlfriend. Shot on a tripod in darkness and light-painted with hand-held LED. 15 sec., 5/4.5, 30mm and, most importantly, since it’s a time exposure, stay at ISO 100. You’ll have plenty of light and keep the noise to a minimum.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS ONE PARTICULAR AREA WHERE, ALL AESTHETIC DEBATES ASIDE, DIGITAL BEATS FILM COLD. That, of course, is in the area of instantaneous feedback, the flexibility afforded to the shooter of adjusting his approach to a project “on the fly”. Simply stated, the shoot-check-adjust-shoot again workflow permitted by digital simply has to prevent more blown shoots and wasted opportunities than film. Shooting a tricky or rapidly changing subject with film can be honed to a pretty sure science, to be sure, especially given years of practice and a keenly trained eye on the part of the person behind the lens. However, a sizable gap of luck, or well-placed guesses remains, a gap narrowed by digital’s ability to speedily provide creative feedback. Release the hounds on me if this makes me a heretic, but as a lover of film, I still prefer the choices digital presents. I don’t have to hate horses to love automobiles.

The digital edge comes through to me especially in table-top shoots executed in darkness and illuminated with selectively “painted” light. I have already written on the general technique I use for these very strange projects in a post called Hello Darkness My Old Friend, so I won’t elaborate on that part again. What I will re-emphasize is that these kind of shots can only be arrived at through a lot of negative feedback, since hand-applied light sources produce drastically different results with every “pass” of the LED, or whatever your source of illumination may be. It’s also hard to find a shot that you love so much that you stop tweaking the process. The next shot just may afford you the quick flick of the wrist that will dramatically shift or redistribute shadows or re-jigger the highlighting of a surface feature.

Tends to fill up those rainy afternoons in a jiffy.

For the above image, I rescued two old dolls from the ash can for one more chance at fame. A friend who knew I was a lifelong Sinatra fan gifted me years ago with a beautifully detailed figure of Ol’ Blue Eyes in his trademark fedora and trench coat, the perfect get-up for hanging out underneath lonely, dim streetlights after all the bars have closed. The other figure is of course a Barbie, left behind when my stepdaughter headed off for college. Normally, these two characters wouldn’t exist in the same universe, and that was what struck me as fun to fool around with. I started to see Barbs as just one of a series of romantic conquests by The Voice on his way through the Universe of Total Coolness, with the inevitable bust-up happening on a dark street in the wee small hours of the morning.

For this shot, the idea was to light just enough of Frankie from above to suggest the aforementioned street lamp, accentuating the textures in his costume and the major angles of his face, without making his head glow so much as to underscore the fact that, duh, it’s made of plastic. The old Barbie had major hairdo issues, but hey, that’s why God made shallow focus. What I got wasn’t perfect, but then, it never is. The important thing with these projects is to make something up and make something come alive, to some degree.

Sadly, Barbie was probably the best thing that ever happened to the Chairman, something he’ll no doubt realize further down that long, lonesome road, looking for answers at the bottle of a shot glass. Hey, his loss.

So goodbye, babe and Amen / Here’s hoping we’ll meet now and then / It was great fun / But it was just one of those things…..

Related articles

- Swank or Rank? Frank Sinatra’s Former Penthouse Hits the Market for $7.7 M. (observer.com)

- tips for fun “everyday” photos. (eliseblaha.typepad.com)

- Hello Darkness My Old Friend (thenormaleye.com)

SUM OF THE PARTS

No one home? On the contrary: the essence of everyone who has ever sat in this room still seems to inhabit it. 1/25 sec., f/5.6, ISO 320, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ANNIE LIEBOVITZ, ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST INNOVATIVE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHERS, people are always more than they seem on the surface, or at least the surface that’s offered up for public consumption. Her images manage to reveal new elements in the world’s most familiar faces. But how do you capture the essence of a subject that can’t sit for you because they are no longer around…literally? Her recent project and book, Pilgrimage, eloquently creates photographic remembrances of essential American figures from Lincoln to Emerson, Thoreau to Darwin, by making images of the houses and estates in which they lived, the personal objects they owned or touched, the physical echo of their having been alive. It is a daring and somewhat spiritual project, and one which has got me to thinking about compositions that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Believing as I do that houses really do retain the imprint of the people who lived in them, I was mesmerized by the images in Pilgrimage, and have never been able to see a house the same way since. We don’t all have access to the room where Virginia Woolf wrote, the box of art chalks used by Georgia O’ Keefe, or Ansel Adams’ final workshop, but we can examine the homes of those we know with fresh eyes, finding that they reveal something about their owners beyond the snaps we have of the people who inhabit them. The accumulations, the treasures, the keepings of decades of living are quiet but eloquent testimony to the way we build up our lives in houses day by day, scrap by personal scrap. In some way they may say more about us than a picture of us sitting on the couch might. At least it’s another way of seeing, and photography is about finding as many of those ways as possible.

I spent some time recently in a marvelous old brownstone that has already housed generations of owners, a structure which has a life rhythm all its own. Gazing out its windows, I imagined how many sunrises and sunsets had been framed before the eyes of its tenants. Peering out at the gardens, I was in some way one with all of them. I knew nothing about most of them, and yet I knew the house had created the same delight for all of us. Using available light only, I tried to let the building reveal itself without any extra “noise” or “help” from me. It made the house’s voice louder, clearer.

We all live in, or near, places that have the power to speak, locations where energy and people show us the sum of all the parts of a life.

Thoughts?

OPTING FOR IMPERFECTION

When additional detail needs to be extracted from shadows and from the texture of materials, HDR (High Dynamic Range) is a great solution. This shot of the entrance to the New York Public Library is a three-exposure bracket composited in Photomatix. Is this process great for all images of the same subject? See a different approach below….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOMETIMES I LOSE MY WAY, CREATIVELY. Given that cameras are technical devices and not creative entities, we all do. We have been given, in today’s market, wonderful aids to seeing and interpreting what we consider noteworthy. Technological advances are surging so swiftly in the digital era that we are being given scads of pre-packaged effects that are baked into the brains of our cameras, ideally designed to help us calculate and fail less, succeed and create more. To that end, we are awash in not only genuinely beneficial shortcuts like programmable white balance and facial recognition, but “miniature”, sketch, selective desaturation, and, recently, in-camera HDR options as well. Something of a tipping point is occurring in all this, and maybe you feel it as strongly as I do; more and more of our output feels like the camera, the toys, the gimmicks are dictating what gets shot, and what it finally looks like.

Here’s the nugget in all this: I have been wrestling with HDR as both a useful enhancer and a seductive destroyer for about three years now. Be assured that I am no prig who sees the technique as unworthy of “pure” photography. Like the old masters of burning and dodging, multiple exposure, etc., I believe that, armed with a strong concept, you use whatever tool it takes to get the best result. And when it comes to rescuing details in darker patches, crisping up details in certain materials like brick and stone, and gently amplifying color intensity, HDR can be a marvelous tool. Where it becomes like crack is in coming to seem as if it is the single best gateway to a fully realized image. That is wrong, and I have more than a few gooey Elvis-on-black-velvet paintings that once had a chance to be decent pictures, before they were deep-fried in the conceptual Crisco of bad HDR. Full disclosure: I also have a few oh-wow HDR images which delivered the range of tone and detail that I honestly believe would have been beyond my reach with a conventional exposure. The challenge, as always, is in not using the same answer to every situation, and also to avoid using an atomic bomb to swat a fly.

Same library, different solution: I could have processed this in HDR in an attempt to pluck additional detail from the darker areas, but after agonizing over it, I decided to leave well enough alone. The exposure was a lucky one over a wide range of light, and it’s close enough to what I saw without fussing it to death and perhaps making it appear over-baked. 1/30 sec., f/6.3, ISO 320, 18mm.

Recently, I am looking at more pictures that are not, in essence, flawless, and asking, how much solution do I need here? How much do I want people to swoon over my processing prowess versus what I am trying to say? As a consequence, I find that images that I might have reflexively processed in HDR just a few weeks ago, are now agonized over a bit longer, with me often erring on the side of whatever “flaws” may be in the originals. Is there any crime in leaving in a bit more darkness here, a slight blowout in light there, if the overall result feels more organic, or dare I say, more human? Do we have to banish all the mystery in a shot in some blind devotion to uniformity or prettiness?

I know that it was the camera, and not me, that actually “took” the picture, but I have to keep reminding myself to invest as much of my own care and precision ahead of clicking the shutter, not merely relying on the super-toys of the age to breathe life into something, after the fact, that I, in the taking, could not do myself. I’m not swearing off of any one technique, but I always come back to the same central rule of the best kind of photography; do all your best creative work before the snap. Afterwards, all your best efforts are largely compensation, compromise, and clean-up.

It’s already a divine photographic truth that some of the best pictures of all time are flawed, imperfect, incomplete. That’s why you go back, Jack, and do it again.

The journey is as important as the destination, maybe more so.

Thoughts?

Related articles

TRAVEL JITTERS

“Autumn in New York, why does it seem so inviting?” A shot inside Central Park, November 2011. 1/60 sec., f/5.6, ISO 160, 50mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF THERE IS SUCH A THING AS PHOTOGRAPHIC STAGE FRIGHT, it most likely is that vaguely apprehensive feeling that kicks in just before you connect with a potentially powerful subject. And when that subject is really Subject One, i.e., New York City, well, even a pro can be forgiven a few butterflies. They ain’t kidding when they sing, if I can make it there I can make it anywhere. But, of course, the Apple is anything but anywhere…….

Theoretically, if “there are eight million stories in the Naked City”, you’d think a photographer would be just fine selecting any one of them, since there is no one single way of representing the planet’s most diverse urban enclave. And there are over 150 years of amazing image-making to support the idea that every way of taking in this immense subject is fair territory.

And yet.

And yet we are drawn (at least I am) to at least weigh in on the most obvious elements of this broad canvas. The hot button attractions. The “to-do list” locations. No, it isn’t as if the world needs one more picture of Ellis Island or the Brooklyn Bridge, and it isn’t likely that I will be one of the lucky few who will manage to bring anything fresh to these icons of American experience. In fact, the odds are stacked horribly in the opposite direction. It is far safer to predict that every angle or framing I will try will be a precise clone of millions of other visualizations of almost exactly the same quality. Even so, with every new trip to NYC I have to wean myself away from trying to create the ultimate postcard,to focus upon one of the other 7,999,999 stories in the city. Even at this late date, there are stories in the nooks and crannies of the city that are largely undertold. They aren’t as seductive as the obvious choices, but they may afford greater rewards, in that there may be something there that I can claim, that I can personally mine from the rock.

By the time this post is published, I will be taking yet another run at this majestic city and anything additional in the way of stories that I can pry loose from her streets. Right now, staring at this computer, nothing has begun, and everything is possible. That is both exhilarating and terrifying. The way to banish the travel jitters is to get there, and get going. And yes, I will bring back my share of cliches, or attempts at escaping them. But, just like a stowaway on a ship arriving in the New World, something else may smuggle itself on board.

I have to visit my old girlfriend again, even if we wind up agreeing to be just friends.

And, as all photographers (and lovers) do, I hope it will lead to something more serious.

Thoughts?

HELLO DARKNESS MY OLD FRIEND

This still life, designed to recall the “cold war” feel of the tape recorder and other props, was shot in a completely darkened room, and lit with sweeps and stabs of light from a handheld LED, used to selectively create the patterns of bright spots and shadows. Taken at 19 seconds, f/6.3, ISO 100 at 50mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MOST OF THE PICTURES WE TAKE involve shaping and selecting details from subjects that are already bathed, to some degree, in light. “Darkness” is in such images, but it resides peripherally in the nooks and crannies where the light didn’t naturally flow or was prevented from going. Dark is thus the fat that marbles the meat, the characterizing texture in a generally bright palette of colors. It is seasoning, not substance.

By contrast, shooting that begins in total darkness means entering a realm of mystery, since you start with nothing, a blank and black slate, onto which you selectively import some light, not enough to banish the dark, but light that suggests, implies, hints at definition. For the viewer, it is the difference between the bright window light of a chat at a mid-afternoon cafe and the intimacy of a shared huddle around a midnight campfire. What I call “absolute night” shots are often more personal work than just managing to snap a well-lit public night spot like an urban street or an illuminated monument after dusk. It’s teaching yourself to show the minimum, to employ just enough light to the tell the story, and no more. It is about deciding to leave out things. It is an editorial, rather than a reportorial process.

The only constants about “absolute dark” shooting are these:

You need a tripod-mounted camera. Your shutter will be open as long as it takes to create what you want, and far longer than you can hope to hold the camera steady. If you have a timer and/or a remote shutter release, break those out of the bag, too. The less you touch that camera, the better. Besides, you’ll be busy with other things.

Set the minimum ISO. If you’re quickly snapping a dark subject, you can compromise quality with a higher and thus slightly noisier ISO setting. When you have all the time you need to slowly expose your subject, however, you can keep ISO at 100 and banish most of that grain. Some cameras will develop wild or “hot” pixels once the shutter’s open for more than a minute, but for many hand-illuminated dark shots, you can get what you need in far less than that amount of time.

Use some kind of small hand-held illumination. Something about the size of a keychain-sized LED, with an extremely narrow focus of very white light. Pick them up at the dollar store and get a model that works well in your hand. This is your magic wand, with which, after beginning the exposure in complete darkness, you will be painting light onto various parts of your subject, depending on what kind of effect you want. Get a light with a handy and responsive power switch, since you may turn the light on and off many times during a single exposure.

You can use autofocus, even in manual mode, but compose and lock the focus when all the room lights are on. Set it, forget it, douse the power and get to work.

Which brings us to an important caveat. Even though you are avoiding the absolute blast-out of white that would result if you were using a conventional flash, lingering over a particular contour of your subject for more than a second or so will really burn a hot spot into its surface, perhaps blowing out an entire portion of the shot. Best way to curb this is to click on, paint, click off, re-position, click back on and repeat the sequence as needed. Another method could involve making slow but steady passes over the subject….back and forth, imagining in your mind what you want to see lit and what you want to remain dark. It’s your project and your mood, so you’ll want to shoot lots of frames and pause between each exposure to adjust what you’re doing, again based on what kind of look you’re going for.

Beyond that, there are no rules, and, over the course of a long shoot, you will probably change your mind as to what your destination is anyhow. No one is getting a grade on this, and the results aren’t going in your permanent file, so have fun with it.

Also shot in a darkened room, but with simpler lighting plan and a shorter exposure time. The dial created its own glow and a handheld light gave some detail to the grillwork. 1/2 sec., 5/4.8, ISO 100, 32mm.

Some objects lend themselves to absolute night than others. For example, I am part of the last generation that often listened to radio in the dark. You just won’t get the same eerie thrill listening to The Shadow or Inner Sanctum in a gaily lit room, so, for the above image of my mid-1930’s I.T.I. radio, I wanted a somber mood. I decided to make the tuning dial’s “spook light” my primary source of interest, with a selective wash of hand-held light on the speaker grille, since the dial was too weak (even with a longer exposure) to throw a glow onto the rest of the radio’s face. Knobs are less cool so they are darker, and the overall chassis is far less cool, so it generally resides in shadow. Result: one ooky-spooky radio. Add murder mystery and stir well.

Flickr and other online photo-sharing sites can give you a lot of examples on what subjects really come alive in the dark. The most intoxicating part of point-and-paint lighting is the sheer control you have over the process, which, with practice, is virtually absolute. Control freaks of the world rejoice.

Head for the heart of darkness. You’ll be amazed what you can see, or, better yet, what you can enable others to see.

Thoughts?

NOTE: If you wish to see comments on this essay, click on the title at the top of the article and they should be viewable after the end of the post.

Related articles

- Lighting Techniques: Light Painting (nikonusa.com)

- Light Writing (cutoutandkeep.net)

SPLITTING THE DIFFERENCE

Really dark church, not much time. An HDR composite of just two exposures to refrain from trying to read the darkest areas and thus keep extra noise out of the final image. Shot at 1/15 and 1/30 sec., both exposures at f/5.6, a slight ISO bump to 200 at 18mm. Far from perfect but something less than a total disaster with an impatient tour group wondering where I wandered off to.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE MOST EXASPERATING WORDS HEARD ON VACATION: Everyone back on the tour bus.

Damn. Okay, just a second.

Now. We’re going NOW.

I’ve almost got it (maybe a different f-stop….? …..no, I’m just standing in my own light….here, let’s try THIS….

I mean it, we’re leaving without you.

YES, right there, seriously, I’m right behind you. Read a brochure will ya? Geez, NOTHING’S working…….

Sound remotely familiar? There seems to be an inverse proportion of need-to-result that happens when an entire group of tourists is cursing your name and the day you ever set eyes on a camera. The more they tap their collective toe wondering what’s taking so looooong, the farther you are away from anything that will, even for an instant, give you a way to get on that bus with a smile on your face. It’s like the boulder is already bearing down on Indiana Jones, and, even as he runs for his life, he still wonders if there’d be a way to go back for just one more necklace….

Dirty Little Secret: there is no such thing as a photo “stop” when you are part of a traveling group. At best it’s a photo “slow down” unless you literally want to shoot from the hip and hope for the best, which doesn’t work in skeet shooting, horseshoes, brain surgery, ….or photography. Dirty Little Secret Two: you are only marginally welcome at the tomb or cathedral or historically awesome whosis they’re dragging you past, so be grateful we’re letting you in here at all and don’t go all Avedon on us. We know how to handle people like you. We’re taking the next delay out of your bathroom break, wise guy.

A recent trip to the beautiful Memorial Church at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California was that latest of many “back on the bus” scenarios in my life, albeit one with a somewhat happy outcome. Dedicated in 1903 by the surviving widow of the school’s founder, Leland Stanford, the church loads the eye with borrowed styles and decorous detail from a half-dozen different architectural periods, and yet, is majestic rather than noisy, a tranquil oasis within a starkly contemporary and busy campus. And, within seconds of having entered its cavernous space as part of a walking campus tour, it becomes obvious that it will be impossible to do anything, image-wise, other than selecting a small part of the story and working against the clock to make a fast (prayerful) grab. No tripods, no careful contemplation; this will be meatball surgery. And the clock is ticking now.

So we ducked inside. With many of the church’s altars and alcoves shrouded in deep shadow, even at midday, choices were going to be limited. A straight-on flash was going to be an obscene waste of time, unless I wanted to see a blown-out glob of white, three feet in front of me, the effect of lighting a flare in a cave. Likewise, bumping my Nikon’s ISO high enough to read a greater amount of detail was going to be a no-score, since the inner darkness was so stark, away from the skylight of the central basilica dome, that I was inviting enough noise to make the whole thing look like a kid’s smudged watercolor. No, I had to find a way to split the difference; Show some of the light and let the darkness alone.

Instead of bracketing anywhere from 3 to 5 shots in hopes of creating a composite high dynamic range image in post production, I took a narrower bracket of two. I jacked the ISO for both of them just a bit, but not enough to get a lethal grunge gumbo once the two were merged. I shot for the bright highlights and tried to compose so that the light’s falloff would suggest the detail I wouldn’t be able to actually show. At least getting a good angle on the basilica’s arches would allow the mind to sketch out the space that couldn’t be adequately lit on the fly. For insurance, I tried the same trick with several other compositions, but by that time my wife was calling my cel from outside the church, wondering if I had fallen into the baptismal font and drowned.

Yes, right there, I’m coming. Oh, are you all waiting for me? Sorry…..

Perhaps its the worst kind of boorish tourism to forget that, when the doors to the world’s special places are opened to you, you are an invited guest, not some battle-hardened newsie on deadline for an editor. I do really want to be nice. However, I really want to go home with a picture,too, and so I remain a work in progress. Perhaps I can be rehabilitated, and, for the sake of my marriage, I should try.

And yet.

Related articles

- The Ultimate Guide to HDR Photography (pixiq.com)

BEYOND THE THING ITSELF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU NO DOUBT HAVE YOUR OWN “RULES” as to when a humble object becomes a noble one to the camera, that strange transference of energy from ordinary to compelling that allows an image to do more than record the thing itself. A million scattered fragments of daily life have been morphed into, if not art, something more than mundane, and it happens in an altogether mysterious way somewhere between picking it and clicking it. I don’t so much have a list of rules as I do a sequence of instincts. I know when I might have stumbled across something, something that, if poked, prodded or teased out in some way, might give me pleasure on the back end. It’s a little more advanced than a crap shoot and a far cry from science.

With still life subjects, unlike portraits or documentary work. there isn’t an argument about the ethics or “purity” of manipulating the material….rearranging it, changing the emphasis, tweaking the light. In fact, still lifes are the only kinds of pictures where “working it” is the main objective. You know you’re molding the material. You want to see what other qualities or aspects you can reveal by, well, kind of playing with your food. It’s like Richard Dreyfuss shaping mashed potatoes into the Devil’s Tower.

If I have any hard and fast rule about still lifes, it may be to throw out my trash a little slower. I can recall several instances in which I was on my way the garbage can with something, only to save it from oblivion at the last minute, turn it over on a table, and then try to tell myself something new about it from this angle or that. The above image, taken a few months ago, was such a salvage job, and, for reasons only important to myself, I like what resulted. Hey, Rauschenburg glued egg cartons on canvas. This ain’t new.

My wife had packed a quick fruit and nut snack into a piece of aluminum foil, forgot to eat it, and brought it back home in her lunch sack. In cleaning out the sack, I figured she would not want to take it a second day and started to throw it out. Re-wrapped several times, the foil now had a refractive quality which, in conjunction with window light from our patio, seemed to amp up the color of the apple slice and the almonds. Better yet, by playing with the crinkle factor of the foil, I could turn it into a combination reflector pan and bounce card. Five or six shots worth of work, and suddenly the afternoon seemed worthwhile.

I know, nuts.

Fruits and nuts, to be exact. Hey, if we don’t play, how will we learn to work? Get out on the playground. Make the playground.

And inspect your trash as you roll it to the curb.

Hey, you never know.

Thoughts?

A QUIET VOICE, A STILL SOUL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

As I have practiced it, photography produces pleasure by its simplicity. I see something special and show it to the camera. A picture is produced. The moment is held until someone sees it. Then it is theirs. -Sam Abell, STAY THIS MOMENT, 1990

The voyage and the vehicle: Sam Abell’s classic image of a canoe on Maine’s Allagash River, the cover image for his book, 1990’s Stay This Moment.

THERE ARE PHOTOGRAPHERS THAT ARE SO AMAZINGLY ADVANCED that they make their images, wrought with love, ferocity, daring, and single-minded purpose, seem not merely visionary but inevitable. We see what they have brought us and exclaim, “of course”, as if theirs is the only way this message could possibly have been crafted, as if its truth is so self-evident that to have to formally recognize it is almost needless overkill. We confirm and validate that, for these pictures, the machine has truly been placed in the service of a soul, and one which writes fluently while we stumble with numb gestures.

One such soul resides in the work of Sam Abell.

If his name doesn’t roll off the top of your tongue alongside those of the obvious Jedi knights of photography, it’s because, for most of his forty-plus year career, he has kept a lower profile than Amelia Earhart, producing amazing work beneath the masthead of National Geographic magazine along with a host of other special commissions. When Sam came to to Geographic in 1967 as an intern, he already had four years of “hard” experience producing images for the University of Kentucky’s school of journalism to his credit, but the magazine’s photo editor, Robert Gilka, was hesitant to hire him, worried that his work was “too artistic”, too personal in its beauty to survive in the service of journalism.

For Abell, it’s all about the patience. How long do you wait for the horse to wistfully glance over his shoulder? As long as it takes…..

With help, Sam Abell learned the balance for getting the facts for stories and getting the truth implied in their locales. Even when those stories’ words shouted with urgency, Sam’s notes were always on the soft pedal. Their poignancy fades in and builds, rises to your attention and then rivets it in place. Writing in his 1990 collection Stay This Moment, Abell declares that the test of great pictures is that “they cannot be memorized”. Small wonder that he began, early in life, to pursue a career on the cello. Smaller wonder yet is that the patience of that instrument is “heard” in the music of his pictures.

Always, a human context. Sam Abell capture of the iconic buildings of the Kremlin, framed by ripening fruit and lace curtains.

Even more muted than the images Sam creates is his technical approach to taking them. For much of his early career, he shot breathtaking landscapes with a simple 35mm camera, often a Leica reflex or rangefinder, mounted with standard or “normal” lenses ranging from 28 to 35mm, generating the least amount of distortion and rendering the most natural relationship of sizes and distances. For years, the most advanced tools in his bag were a sturdy Gitzmo tripod and the slowest, richest films he could find, frequently Kodachrome 25 and 64. The tripod delivered the stability needed to produce slow, sensual exposures; the ‘Chrome delivered texture and nuance beyond the power of hand-held shots. However, the most vital weapon in Abell’s arsenal is his astonishing patience, the wisdom, which flies in the face of traditional journalism photography, to wait for the story in a picture to slowly unfold, like the petals of a flower. Some of the best images Abell placed in National Geographic over the years took nearly a year to create. It happens when it happens, and once it does, God is it worth it.

The number of printed collections of Sam’s work are few and far between, given his enormous output, but diligence rewards the curious. Among the most available of them is the collaboration undertaken with historian Steven Ambrose, Lewis & Clark: Voyage of Discovery ( 2002), for which Sam created images of the surviving sections of the legendary explorers’ trail to the Pacific; Amazonia (2010), an essay on the kind of delicate ecosystems that are vanishing from the earth; and Life of a Photograph (2008), an examination of how his most famous pictures were built, stage by stage. And, of course, there is the luxuriant (and hopelessly out-of-print) Stay This Moment (1990), the companion book to his mid-career exhibition at New York’s International Center for Photography. Buy it in a used book shop, grab it on e-Bay, scour your local library, but find this book.

More importantly, find Sam’s work…any of it…and savor every detail. For copyright protection purposes, I have deliberately kept the illustrations in this article constrained to minimal resolutions. Find the real stuff, and see what Abell’s amazing sweep and scope can do at full-size. This blog is chiefly about how I, as a rank amateur, struggle with my own creative conundrums. But it is also about knowing what teachers to bend toward. Sam Abell, who literally teaches in mentor programs all over the country, has a powerful gift to impart. “What is right?”, he asked in 1990. “Simply put, it is any assignment in which the photographer has a significant emotional stake.” He also emphasized an important distinction (one of my favorites) in his remarks to a young photography student. Don’t say, he said, I took this picture.

Say instead, I made this picture.

Of course.

Thoughts?

Related articles

- Sam Abell Interview (keronpsillas.com)

- The Life of a Photographer – Sam Abell (billives.typepad.com)

180 DEGREES

This image, the reason I ventured out into the night, originally eluded me, causing me to turn a half circle to discover a totally different scene and feel waiting just over my shoulder. 20 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 20mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WISH I HAD A LEICA for every time I came away from a shooting project with something completely opposite from the prize I was originally seeking. The odd candid moment, the last-minute change of light, the bizarre intervening event….there are so many random factors even in the shots that are the most meticulously planned that photography is kept perpetually fresh, since it is absolutely impossible to ensure its end results, especially for infants playing at my level. That point was dramatically brought home to me again a few weeks ago, and all I had to do was turn my head 180 degrees.

All during a week’s stay at a conference center near Yosemite National Park, I had been struck by how the first view a visitor got of the main lodge and its surrounding pond, from an approach road slightly above the building, was by far a better framing of the place than could be had anywhere else on the grounds. A few days of strolling by the lodge from several approaches had not provided any better staging of the quiet scene, but, with the harshness of the daylight at that altitude, I was convinced that a long exposure done just after nightfall would convey a more peaceful, intimate mood than I could ever hope to capture by day. And so, on the evening before I was to leave the lodge for home, I decided to take my tripod to the approach road and set up for a try.

The road is rather twisty and narrow, and so its last turn before heading for the lodge’s parking areas is lit with a street lamp, and a bloody bright one at that. It’s a sodium vapor light, which registers very orange to the eye. I’m used to these monsters, since, back home in Phoenix, they are the predominant city light sources, creating less long-distance “light pollution” for astronomers in Flagstaff trying to see the finer features in the night sky. At any rate, the road was so bright that I had to set up closer to the lodge than originally planned in order to avoid a lot of ambient light over my shoulder killing the subdued dark I wanted for my shot. Intervening event and last-minute change of light. Changing my stance, I was also having problems with movement on the pond surface. It was a tad too swift to allow for a mirroring of the lodge, and a long exposure was going to soften it up even more. I was going to get pretty colors, but they would be diffuse and gauzy rather than reflective. At the same time I was trying to avoid framing another lamp, this one to the right of the lodge. Illuminating a walking path, it would, over the length of the exposure, pretty much burn its way into the scene and distract from the impact. Typical problems, but I was already losing my love for the project, and after about a half-dozen flubbed attempts, I was trying to avoid mouthing several choice Anglo-Saxon epithets.

It was the need to take a break that had me looking around to see if anything else could be done under the conditions, and that’s when I turned my head to really see the light from the approach road that had been over my shoulder. Candid moment. Now I saw that orange light illuminating the road, the rustic fence, and the surrounding trees and shrubs in an eerie, Halloween-ish cast. The same scene in daylight or natural color would have registered just as “some nice trees”, but now it was Sleepy Hollow, the scary walk home after the goblins come out, the place where evil things breed. Better yet, if I stepped just about six inches to the right of where I was standing, the hated lamp-post would be totally obscured by the largest tree in the shot, casting its shadow another 20 or so feet longer and serving up a little added drama as a bonus. Suddenly, the lamp had been transformed from a fiend to a friend. I swiveled the tripod’s head around, set the shot, and got where I needed to be in two clicks.

After first trying (and failing) to nail the image of the lodge, I pivoted around and found this scene, which had been waiting to be discovered right behind me. Once I shot this, I turned around and made one more attempt on the lodge, using, as it turned out, the exact same setting as this picture; 20 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 20mm.

Better yet, the break in the action allowed me to re-boot my head vis-a-vis the lodge image. I turned back around, and, oddly, with the exact same exposure settings, hit a balance I could live with. Neither shot was perfect, but the creation of one had actually enabled the capture of the other. On the walk back to my cabin, I was already dissecting the weaknesses in both, but they each, in turn, had taught me, again, the hardest lessons, for me, in photography. Slow down. Look. Think. Plan, but don’t be afraid of reactive instinct. Sometimes, a sacred plan can keep you from “getting the picture”, figuratively and literally.

All I have to do is remember to turn my head around.

ASKING THE MOUNTAINS TO SAY “CHEESE”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK IS A SUPREME PARADOX FOR A SHOOTER. On one hand, it has never been technically easier to simulate the texture and range of tones that were hard-won miracles for its guardian angel, Ansel Adams. On the other, the very act of visiting the park has never presented a more severe barrier to the kind of mental and emotional commitment to picture making that was, to him, a constant.

The original mission of this blog is to share creative successes from amateur to amateur, but also to name the problems which restrict us to taking, instead of making, pictures. Yosemite, historically the proving ground for photographers the world over, also presents one of these problems.

Adams had to suffer, slog, hike, and persevere to set up his visions, all the while wrestling with a technology that punished the slightest miscalculation. The park itself presented a rugged challenge to him as well in the early 20th century, as its greatest vistas were not just a minivan jog away and its best treasures resisted his inquiring eye. So how come his pictures are so much better, still, than anything most of us can deliver in an age of ultimate simplicity, ease, and access?

There is a disturbing statistic quoted by the park service, that the average visitor to Yosemite is actually in the park for a grand total of two and a half hours. Not exactly the time investment that a photographic subject of this scope warrants. We also tend to enter the park in much the same way, stop by a predictable list of features, and take most of the same “money shots”. We all know where the good stuff is, and it seems to be irresistible to offer up our “take” on the craggy face of El Capitan, the serene power of the Mariposa Grove (with its astonishing giant sequoias), or the obligatory capture of a waterfall….hell, any waterfall. And yet….I can’t be the only one who has come home from vacation to find that my pictures are just….okay. Overwhelmingly…..non-sucky. Stunningly….passable.

Adams’ life’s work, a mutual exchange of energy in which he and Yosemite were creative partners in the deliberate making of images, is, for us, a re-creation, a simulation, the photo equivalent of karaoke. Just like many lounge lizards “kinda” sing like Sinatra, too many of us “kinda” shoot pictures like Ansel. For Adams, photography was like asking the wilderness to dance. For us, it’s like asking the mountains to say “cheese”.

Part of his mission was showing us what a treasure we had, but he might have sold the product too well. Part of the Yosemite that spoke to him is gone, compromised into tameness by sidewalks,snack bars, and gift shops. Worse, much of what we do choose to record of it is done in quick stops off the tour bus, stolen moments before the kids get too tired , and the rabid urgency of God-let’s-hurry-up-we-have-three-more-places-to-hit-today. Indeed, park officials laughingly refer to people who drive in and out of the park’s main areas without even emerging from their cars, bragging that they “did” Yosemite, like a ten minute rock wall climb at REI, squeezed in before a trip to the food court.

The Ansel Adams Gallery, which has operated in the park for more than a century now, certainly features fresh visions by new artists who are still re-interpreting the wonder, still managing to say something unique. But many of our cameras will betray how little of our selves are invested behind the viewing screen. Adams’ work resonates through time because we recognize when someone has poured part of their soul into the creative cauldron. And certainly, if we are honest, we also know when that ingredient is missing.

“I want to see your face in every kind of light” goes the old love song lyric. Being in love with a woman, an idea, anything, demands time, deliberation. To see the object of one’s affection in all light, all seasons, all moods and tempers, is more of a pact than many of us are willing to make. The pictures we bring back from many places may not be lessened in their impact by this fact. But Yosemite is not “many places”, and she will not give up her secrets to just anyone. Fortunately, if we care, we can return and try again to do more than merely tattoo pixels onto a sensor. That has always been the promise of photography, that you can redeem your myopia from one day by re-thinking, re-feeling on another. But it means changing the rules of engagement with our subject. For those of us who cannot or will not do that, the world will not stop spinning, and, in fact, we will chalk up many acceptable images along the way, but Ansel will always be the one among us who really understood the magic, and discovered how to conjure it at will.

Related articles

- What’s black & white, famous, and coming to Peabody? (hangwithbigpictureframing.com)

- A Weekend in Yosemite (theepochtimes.com)

SMILE! OR NOT.

Since we’re usually unhappy with the way others capture us, we have nothing to lose by a making a deliberate effort to come closer to the mark ourselves. Self-portraits are more than mere vanity; they can become as legitimate a record of our identities as our most intimate journals. 1/15 sec., f/7.1, ISO 250, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A COMMONLY HELD VIEW OF SELF-PORTRAITURE is that it epitomizes some kind of runaway egotism, an artless symbol of a culture saturated in narcissistic navel-gazing. I mean, how can “us-taking-a-picture-of-us” qualify as anything aesthetically valid or “pure”? Indeed, if you look at the raw volume of quickie arm’s length shots that comprise the bulk of self-portrait work, i.e., here’s me at the mountains, here’s me at the beach, etc., it’s hard to argue that anything of our essence is revealed by the process of simply cramming our features onto a view screen and clicking away…..not to mention the banality of sharing each and every one of these captures ad nauseum on any public forum available. If this is egotism, it’s a damned poor brand of it. If you’re going to glorify yourself, why not choose the deluxe treatment over the economy class?

I would argue that self-portraits can be some of the most compelling images created in photography, but they must go beyond merely recording that we were here or there, or had lunch with this one or that one. Just as nearly everyone has one remarkable book inside them, all of us privately harbor a version of ourselves that all conventional methods of capture fail to detect, a visual story only we ourselves can tell. However, we typically carry ourselves through the world shielded by a carapace of our own construction, a social armor which is designed to keep invaders out, not invite viewers in. This causes cameras to actually aid in our camouflage, since they are so easy to lie to, and we have become so self-consciously expert at providing the lies.

The portraits of the famous by Annie Liebovitz, Richard Avedon, Herb Ritts and other all-seeing eyes (see links to articles below) have struck us because they have managed to penetrate the carapace, to change the context of their subjects in such dramatic ways that they convince us that we are seeing them, truly seeing them, for the first time. They may only be doing their own “take” on a notable face, but this only makes us hunger after more interpretations on the theme, not fewer. Key to many of the best portraits is the location of their subjects within specific spaces to see how they and the spaces feed off each other. Sometimes the addition of a specific object or prop creates a jumping off point to a new view. Often a simple reassignment of expression (the clown as tragedian, the adult as child, etc) forces a fresh perspective.

As for the self-portrait, an artistic assignment that I feel everyone should perform at least once (as an intentional design, not a candid snap), there is a wealth of new information gleaned from even an indifferent result. Shooters can act as lab rats for all the ways of seeing people that we can think of to play at, serving as free training modules for light, exposure, composition, form. I am always reluctant to enter into these projects, because like everyone else, I balk at the idea of centering my expression on myself. Who, says my Catholic upbringing, do I think I am, that I might be a fit subject for a photograph? And what do I do with all the social conditioning that compels me to sit up straight, suck in my gut, and smile in a friendly manner?

One can only wonder what the great figures of earlier centuries might have chosen to pass along about themselves if the self-portrait has existed for them as it does for us. What could the souls of a Lincoln, a Jefferson, a Spinoza, an Aquinas, have said to us across the gulf of time? Would this kind of introspection been seen by them as a legacy or an exercise in vanity? And would it matter?

In the above shot, taken in a flurry of attempts a few days ago, I am seemingly not “present” at the proceedings, apparently lost in thought instead of engaging the camera. Actually, given the recent events in my life, this was the one take where I felt I was free of the constraints of smiling, posing, going for the shot, etc. I look like I can’t focus, but in catching me in the attempt to focus, this image might be the only real one in the batch. Or not. I may be acting the part of the tortured soul because I like the look of it. The point is, at this moment, I have chosen what to depict about myself. Accept or reject it, it’s my statement, and my attempt to use this platform to say something, on purpose. You and I can argue about whether I succeeded, but maybe that’s all art is, anyway.

Thoughts?

Related articles

- Avedon For Breakfast (fabsugar.com)

- Getty Center Exhibits Herb Ritts and Celebrity Portraits (ginagenis.wordpress.com)

- Annie Leibovitz: ‘Creativity is like a big baby that needs to be nourished’ (guardian.co.uk)

GLO-SCHTICK

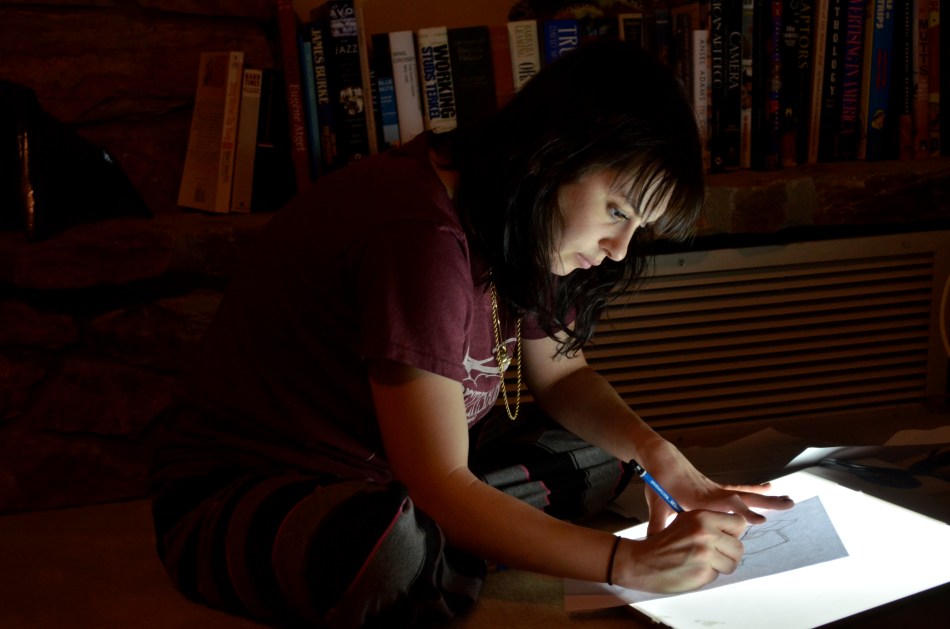

Sometimes just a bit is just enough. A bump up to ISO 640 kept me fairly free of noise and allowed me to use the screen’s glow as my only light source. 1/30 sec., f/5.6 at 52mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE BEST TECHNIQUE is one that does not scream for attention like a neon t-shirt emblazoned with the phrase LOOK WHAT I DID.

Now, of course, we are all messing around backstage, working hard to make the elephant disappear. We all manipulate light. We all nudge nature in the direction we’d prefer that she go. But what self-respecting magician wants to get caught pulling the rabbit out of a hole in the table?

I recently had the perfect low-light solution handed to me as I watched a young designer working in a dim room, and, thankfully, only marginally aware of my presence. “Lighting 101” dictated that, to get a sense of her intense concentration, I send the most important light right to her face.

Turns out, a light tracer screen, in a pinch, makes a perfect softbox.

Better yet, the light from the screen thinned out and dampened after it traveled left past her shoulders, leaving just enough illumination to keep the rest of the frame from falling off completely into black, making the face the lone story-teller. An ISO bump to 640 and a white balance tweak were enough to grab the best of what the screen had to give. At this point in the “gift from the gods” process, you click, and promise, in return, to live a moral life.

Sometimes you don’t have to do anything extra to make a thing look like it actually was. That’s better than finding a hundred-dollar bill on the street.

Well, almost.

What was your best light luck-out?

BAM!

My early morning “garage studio”, an impromptu place to stage objects large and small, lit by an early morning blast of Arizona sun. 1/160 sec., f/6, ISO 100, 18mm.

THERE IS A DELIGHTFUL SEQUENCE toward the end of Martin Scorsese’s Hugo which shows the silent movie pioneer George Melies creating films in his own primitive studio in France. Like Thomas Edison, who built the Black Maria, a tarpaper shack that rotated on a turntable so its roof and front wall could be turned toward the sun for all-day shooting, Melies improvised his own turn-of-the-century solution for how to get adequate light to slow film. Like Edison, he built his studio to stand out in the open sun, but fashioned its walls completely of glass, huge panes mounted inside a simple metal frame cage. The frame held fixtures and scenery in place, and its spartan design gave Melies a pure, huge, natural light box inside which he directed the first minor masterpieces of world cinema. It’s a reminder of how truly elementary some of our light problems are. Just put yourself at the service of the available light and be ready to make magic….in seconds.

The point is, most of us probably have daily access to at least one “sweet” spot, either in our houses, or the yards and grounds that surround them, or somewhere near us, where there is abundant, reliable light, on a daily basis, sufficient to shoot almost anything..without muss, fuss, or flash. For me, it’s the southeast corner of the house, where the blazingly, brilliant Arizona morning light comes slamming in by way of the opened garage door, the front entrance sidelights, or the west window near where I am posting this. And when I say light, I mean BAM! light, with long, solid shadows and, just after dawn, a super-saturation of color that will vanish by midday, when the western sky is one big blinding, squinting, over-exposed whiteout.

In recent months, I have actually created crude mini-studio areas at these various BAM! points, staging objects on everything from snack tables to packing cartons, baffling or channeling the light in some cases with strips of cardboard or towels, but mostly just placing still-life objects right in the path of these killer rays. On occasion, I am rewarded with a great image before breakfast, which is a psychologically great way to put the right early spin on the day.

Same staging area, different day. This tight shot on one of my ukes was set up lying on its back, held aloft on a tall packing carton. 1/160 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 30mm.

It also harks back to my childhood and the five dollar Imperial box camera that started it all. With one focal length and one shutter speed, you had to be cagey, to, in fact, get any image in other than ideal light. There was, to say the least, a high fail rate. Next time you stop by the house I can show you the shoebox of shame, wherein lie interred all the keepers that might have been. Rest in Peace.

A translucent souvenir paperweight from the 1939 New York World’s Fair, made into a kind of glow torch courtesy of morning light shining on my dining room table. 1/500 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 55mm.

Part of my mad pursuit of available light has been fed, in recent years, by the adventure I undertook of shooting exclusively with a 50mm f/1.8 prime lens for an entire year. Freed by this wonderful glass to attempt an ever wider scope of do-able shots, I did everything I could to push the envelope in whatever situation I could devise. Eventually I compiled a book of the luckiest results entitled The Normal Eye, and was left with a renewed passion for low-and- no-light opportunities.

Find the BAM! spot around your crib and have your own Melies moment. Turns out, the tools we need are never far off.

Make light of the situation.

Thoughts?

(The Normal Eye is available through Blurb Books at www.blurb.com/bookstore