REVELATION OR RUT?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S OFTEN DIFFICULT FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS, UNDER THE SPELL OF A CONCEPT, TO KNOW WHETHER THEY ARE MARCHING TOWARD SOME LOFTY QUEST or merely walking in circles, their foot (or their brain) nailed to the floor. Fall too deeply in love with a given idea, and you could cling to it, for comfort or habit, long after it has yielded anything remotely creative.

You might be mistaking a rut for revelation.

We’ll all seen it happen. Hell, it’s happened to many of us. You begin to explore a particular story-telling technique. It shows some promise. And so you hang with it a little longer, then a little longer still. One more interpretation of the shot that made you smile. One more variation on the theme.

Maybe it’s abstract grid details on glass towers, taken in monochrome at an odd angle. Maybe it’s time exposures of light trails on a midnight highway. And maybe, as in my own case, it’s a lingering romance with dense, busy neighborhood textures, shot at a respectfully reportorial distance. Straight-on, left to right tapestries of doors, places of business, upstairs/downstairs tenant life, comings and goings. I love them, but I also worry about how long I can contribute something different to them as a means of telling a story.

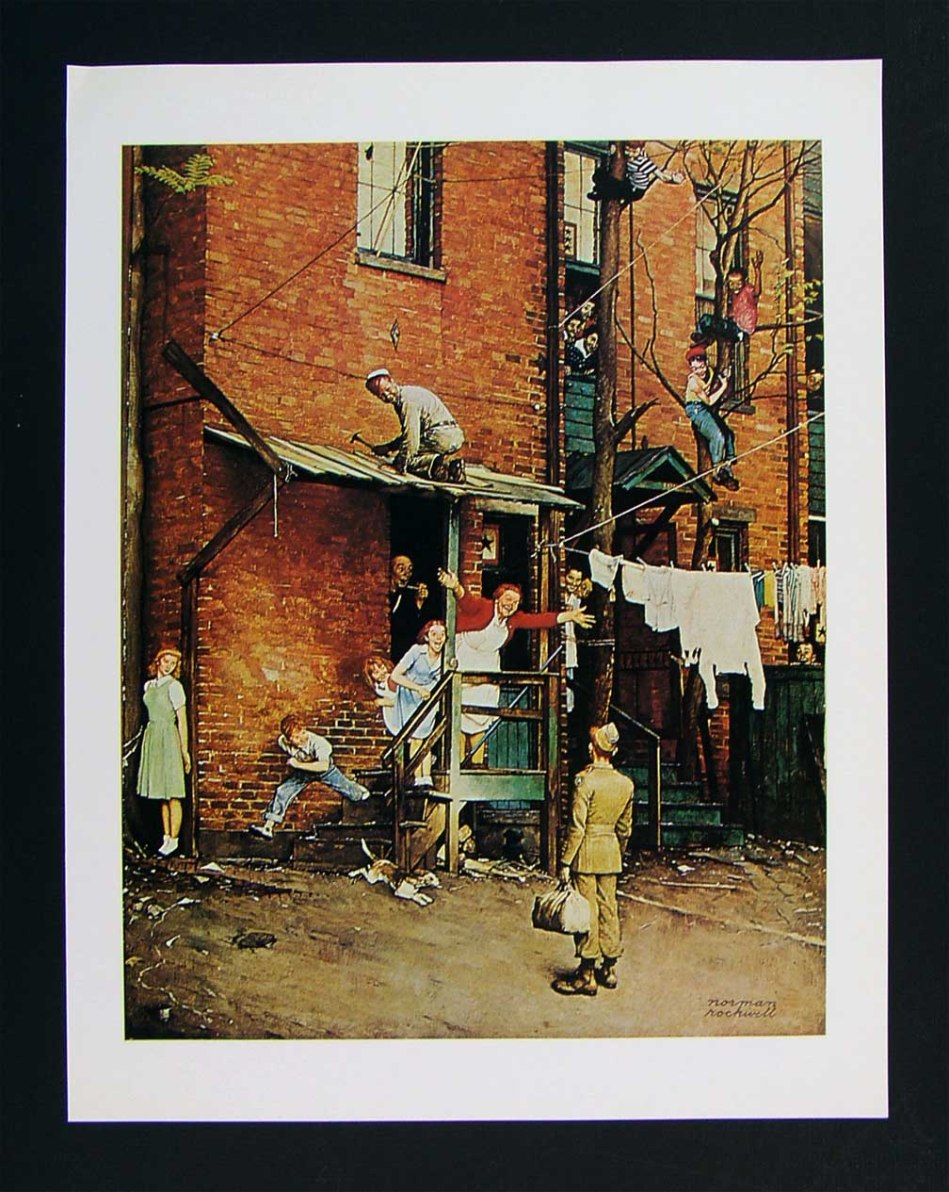

As staged as a Broadway show, Norman Rockwell’s idealized neighborhoods are still alluring in their appeal.

- The bustling tenement neighborhoods of early Norman Rockwell paintings appealed to me, as a child, because the frames were teeming with life: people leaning out of windows, sitting on porches, perching on fire escapes, delivering the morning milk…they were a divine, almost musical chaos. But they were paintings, with all the intentional orchestration of sentiment and nostalgia that comes with that medium. Those images were wonderful, but they were not documents…merely dreams.

That, of course, doesn’t make them any less powerful as an influence on photography.

When I look at a section of an urban block, I try to frame a section of it that tells, in miniature, the life that can be felt all day long as the area’s natural rhythm. There are re-gentrified restaurants, neglected second-floor apartments, new coats of paint on old brick, overgrown trees, stalwart standbys that have been part of the street for ages, young lovers and old duffers. Toss all the ingredients together and you might get an image salad that captures something close to “real”. And then there is the trial-and-error of how much to include, how busy or sparse to portray the subject.

That said, I have explored this theme many times over the years, and worry that I am trying to harvest crops from a fallow field. Have I stayed too long at this particular fair? Are there even any compelling stories left to tell in this approach, or have I just romanticized the idea of the whole thing beyond any artistic merit?

Hopefully, I will know when to strike this kind of image off my “to do” list, as I fear that repetition, even repetition of a valid concept, can lead to laziness….the place where you call “habit” a “style”.

And I don’t want to dwell in that place.

CONTAIN YOURSELF

The Things They Carried: my wife’s father’s leather instrument case and compass. 1/60 sec., f/5.6, ISO 250, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE LIVE IN AN AGE IN WHICH MOST OF OUR LIVES ARE EXHAUSTIVELY OVER-DOCUMENTED. We are, compared to our recent ancestors, photographically bitmapped from cradle to grave with a constellation of snaps that practically draw an outline around us and everything we do.

Globally, we will take more photographs in two minutes today than the entire world took over the entire 19th century.

That said, it’s amazing how few photos taken of, or by, us really look deeply into our souls, or whatever it is that animates us, makes us truly alive. It’s not that there aren’t enough pictures of us being taken: it’s how inarticulate so many of them are.

But go back just a generation or two, and observe the contrast. Far fewer images of most lives. And, with their increasing rarity or loss, more and more value attached to each and every one of those images that survives. Grandfather is gone, leaving only a handful of curled, cracked, and browning snapshots to mark his passing. But how rich the impact of those remaining pictures. The thirst for more, for a greatest number of clues to who this person was!

How to increase or deepen his spirit without having him here?

Explore the things he left behind. The tools he touched. The places where he invested his spirit, his aura. The parts of the world that he deemed important.

And I say: if you love someone, and have to let them go, use your camera to sniff around the found objects of their lives. It may not conjure them up like a holograph of Obi-Wan, but it will focus your thoughts about them in away which is nearly, well, visual.

I fell in love with the worn little instrument case you see at the top of this page. It belonged to my wife’s father, a man whose life was cut short by illness, a life under-represented in photographs. He made his living with his wits and with his hands. The compass which was carried in this case was a tool of survival, something he used to make his living, to measure out his skill and art. It’s a treasure to have it around to look at, and it’s a privilege to be able to photograph its worn corners, its tattered grain, its rusted buttons. Time has allowed it to speak, louder than its owner ever can, and to act as his visual proxy.

I’ve explored this theme in past posts, because I feel so strongly about the expressive power of things as emblems of lives. Long before our every action could be captured in an endless Facebook page of banal smartphone snaps, images had to work a lot harder, and say more. I’m not saying you should spend the next six months of your life raiding your closets for Ultimate Truth. I am saying you might be walking past a chunk of that Truth every day, and that it might just be worth framing up.

And thinking about.

(let’s help each other find amazing images! Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.)

Related articles

- Behind the lens (theoriginalblogofthecentury.wordpress.com)

- Old Photographs Given New Life (modcloth.com)

AFTER-IMAGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WITHOUT GETTING TOO OVERLY OOKY-SPOOKY, I believe that photographers are witnesses to, well, ghosts. Specializing in the visualization of what might be (as near as our next frame), we are also retro-witnesses, or mediums, if you will, using found objects to call back the spirit of things that are no longer here. “If these walls could talk”, we instinctively remark as we walk into Notre Dame, Independence Hall, or Ellis Island, and yet, we think we are merely being poetic when we utter that phrase.

Are we?

Objects give up their secrets slowly, and in these posts I have often gone back to my fond desire to resurrect at least the essence of the owners of those objects, re-capturing people in the things they held, kept, cherished, wore to pieces, loved to death. We use every atom of our imagination trying to inch forward toward some revelation yet-to-be….a way to will a picture into being. But we are surprised to find ourself also trying to conjure forth echoes. And yet some of the most moving portraits we can produce show no people at all. I’m sure you have found this to be true.

For reasons I don’t quite understand, chairs resonate especially for me. They’re personal. They’re social. Deals are struck in them; stories are told, babies are soothed, pauses are taken, contemplation occurs. Lives pass.

For you, it might be other things that are left behind, but still ringing with the echoes of people. Books. Clothing. Cars. They can be anything, but whatever their strange stories, you can often hear them, and that makes them far from “empty”. Cameras record everything that can be seen and lots of things that can only be sensed. They may be only machines, but in the hands of dreamers they are divining rods.

Your houses are haunted, and in a good way.

Call the spirits forth.

Related articles

- Between objects and life (thehindu.com)

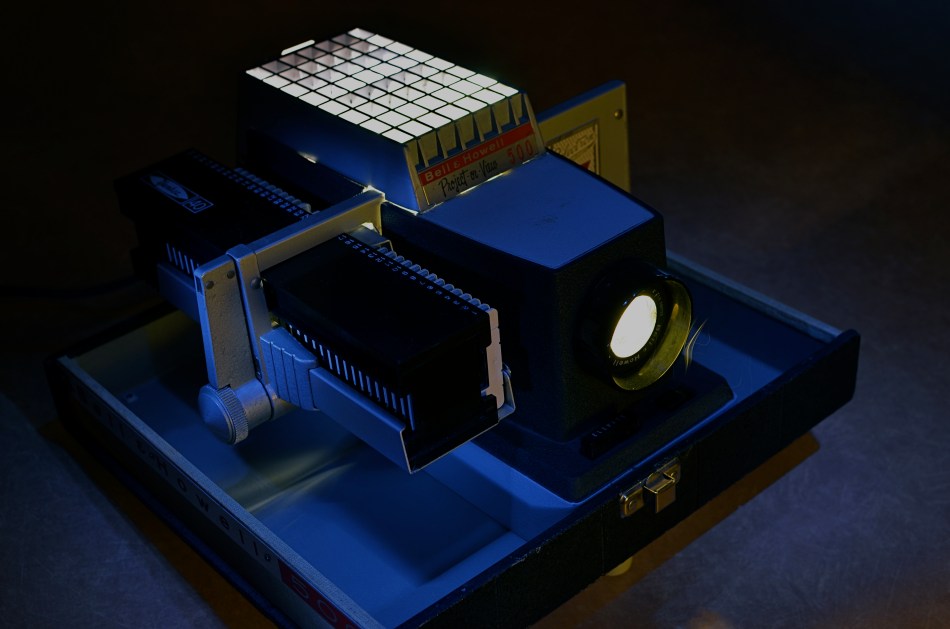

VINTAGE VESSEL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ALTHOUGH SHOOTERS FANCY THEMSELVES “INTERPRETIVE VISUAL POETS”, a big part of photography is also the dutiful marking of time, the chronicling of things that are in the process of going away. The medium of image-making itself is one long history of mutation, evolution and imminent obsolescence, so why should we shy away from recording those things in our world which are always going extinct? Think of the world as one big repeat of your eighth-grade class picture. Yeah.

ALTHOUGH SHOOTERS FANCY THEMSELVES “INTERPRETIVE VISUAL POETS”, a big part of photography is also the dutiful marking of time, the chronicling of things that are in the process of going away. The medium of image-making itself is one long history of mutation, evolution and imminent obsolescence, so why should we shy away from recording those things in our world which are always going extinct? Think of the world as one big repeat of your eighth-grade class picture. Yeah.

I am a lifelong Coca-Cola buff. Part of this fascination comes out of a career in mass media advertising and marketing, where Coke has largely shown the rest of the world how a brand is created and sustained. This fizzy (and guilty) pleasure is probably unique among all of the products ever marketed in the industrial world, coming, as it does, with its own traditions, mythology, and iconography. From the annual seasonal Haddon Sundblom illustrations of Santa Claus pausing to refresh himself to our present-day polar bear soda fantasies, Coke has established a legacy of style and, yes, a certain visual vocabulary. We may argue “new recipe” versus “classic formula”, but we know what Coca-Cola should look like.

I can suggest an elegant cheese to accompany this unique ’95 vintage. Something in a discreet Velveeta, perhaps? A tone-mapped blend of 1/320 and 1/620 sec. exposures on a Nikon 35mm prime lens, both at f/2.5 and ISO of 100.

One of the “looks” that we expect is the sinuous curl of the so-called “contour” bottle, introduced in 1916 and maintained as a constant of style well into the 21st century. This distinctively shaped design was so quintessentially American that it was originally nicknamed the “Mae West” due to its, er, curvaceous dimensions. And when it comes to Coca-Cola, icons die hard. Years after this traditional container has ceased to be the dominant delivery system for Coke products, current commercials still show customers lifting, ta da, a glass bottle to their joyful lips. In everyday practice, of course, nearly all Coke sold in America is encased in plastic, with, by 2012, only a single bottling plant in Winona, Minnesota continuing to refill the 6.5- ounce “green glass” bottles, or “bar Cokes”. By October, rising costs and diminishing returns called a halt to it all, and the last bottles rolled off the line to a chorus of pop culture weeping and wailing.

Some small glass bottles of Coke will continue to be sold at retail going forward, but their graphics are painted on, rather than molded into the glass. Call me a purist, but, as a fan of tabletop still lifes, I thought it was high time the original hand-sized, green glass, America-won-the-war Coca-Cola bottle posed for its closeup. I decided to add a little pomp by way of props to suggest Everyman’s Drink as a fine vintage, but, hey, we all know damn well that we never, ever had a glass of wine that came close to the first burpy sting of a cold swig of The Real Thing.

It’s fun mocking up product shots. It’s even more fun when it’s an act of love.

Still, maybe all those kids singing on the side of a hill in that old TV ad were on to something.

I’d like to buy the world a Coke……

SKIN IN THE GAME

“Old Faithful”, the jacket that has accompanied me on more shoots than any other single piece of “gear”. 1/200 sec., f/2.8, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE ONE PIECE OF “EQUIPMENT” THAT HAS SEEN ME THROUGH THE TRANSITION FROM FILM TO DIGITAL is not a hunk of techno gear. In fact, it has not directly figured in the taking of even a single picture. I was reminded of its amazing longevity a few months ago, as I was going through a 2002 shoot done in Ireland. Among my own shots was a pretty good candid of me, taken by my wife, as I crouched to line up a shot next to a road heading to the Ring of Kerry. And there “it” was with me.

In fact, it was keeping me warm and dry.

Context: I never took the plunge of the eager amateur and purchased one of those puffy, sleeveless photog vests, honeycombed with a zillion pockets, pouches and secret compartments, much as I never painted the words CAMERA NERD on my face in day-glo orange. Chalk it up to self-consciousness. I figured it was hard enough to blend in and keep people relaxed in a shooting situation without looking like a cross between a spinster butterfly hunter and a middle-school lab assistant. Call me vain.

And you’d be right.

So, a plain brown leather jacket. Gimme three good pockets and call it day. And thus it was that, for the next thirteen years or so, I have had “skin in the game”, skin that has survived exploded pens, leaked batteries, rotten weather on two sides of the Atlantic, and more scrapes, tears, and rips than I care to recall. It has also helped keep countless camera straps from inscribing a permanent groove in my left shoulder, and, here in the Land Of Incipient Arthritis, I appreciate that more than I can say.

Such service calls for a little respect, and so, in the name of the weirdest still lifes ever, I figured it was time for Old Faithful to pose for a portrait of its own. Originally I thought to lay it out straight, the way they show off famous duds at the Smithsonian. But what really caught my eye was that, texture-wise, it is almost six different jackets, from the glossy sheen of an old horse saddle to the frayed look of something that’s been making out with a cheese grater.

At the last, I simply experimented with a few crumpled waves of grain, as if the jacket had been hastily tossed aside, which, trust me, it has been, on countless occasions.

Best thing is, when I’m ready, it’s still there.

I’m not a big fan of good luck charms, but maybe some things protect against bad luck, and that’s no easy feat, either. Either way, me and what Kipling would have called my “Lazarushian leather” and I will keep signing up new missions.

At least until one of our arms fall off.

LET THERE BE (MORE) LIGHT

A new piece of glass makes everything look better….even another piece of glass. First day with my new 35mm prime lens, wide open at f/1.8, 1/160 sec., ISO 100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE RECENTLY BEEN EXPERIENCING ONE OF THOSE TIME MACHINE MOMENTS in which I am, again, right back at the beginning of my life as a photographer, aglow with enthusiasm, ripe with innocence, suffused by a feeling that anything can be done with my little black box. This is an intoxication that I call: new lens.

Without fail, every fresh hunk of glass I have ever purchased has produced the same giddy wonder, the same feeling of artistic invincibility. This time out, the toy in question is a Nikon f/1.8 35mm prime lens, and, boy howdy, does this baby perform. For cropped sensor cameras, it “sees” about like the 50mms of old, so its view is almost exactly as the human eye sees, without exaggerated perspective or angular distortion. Like the 50, it is simple, fast, and sharp. Unlike the 50, it doesn’t force me to do as much backing up to get a comfortable framing on people or near objects. The 35 feels a little “roomier”, as if there are a few extra inches of breathing space around my portrait subjects. Also, the focal field of view, even wide open, is fairly wide, so I can get most of your face tack sharp, instead of just an eye and a half. Matter of preference.

All this has made me marvel anew at how fast many of us are generally approaching the age of flashless photography. It’s been a long journey, but soon, outside the realm of formal studio work, where light needs to be deliberately boosted or manipulated, increasingly thirsty lenses and sensors will make available light our willing slave to a greater degree than ever before. For me, a person who believes that flash can create as many problems as it solves, and that it nearly always amounts to a compromise of what I see in my mind, that is good news indeed.

It also makes me think of the first technical efforts to illuminate the dark, such as the camera you see off to the left. The Ermanox, introduced by the German manufacturer Ernemann in 1924, was one of the first big steps in the quest to free humankind of the bulk, unreliability and outright danger of early flash. Its cigarette-pack-sized body was dwarfed by its enormous lens, which, with a focal length of f/2, was speedy enough (1/1000 max shutter) to allow sharp, fast photography in nearly any light. It lost a few points for still being based on the use of (small) glass plates instead of roll film, but it almost single-handedly turned the average man into a stealth shooter, in that you didn’t have to pop in hefting a lotta luggage, as if to scream “HEY, THE PHOTOGRAPHER IS HERE!!” In fact, in the ’20’s and ’30’s, the brilliant amateur shooter Erich Solomon made something of a specialty out of sneaking himself and his tiny Ermanox into high-level government summits and snapping the inner circle at its unguarded best (or worst). Long exposures and blinding flash powders were no longer part of the equation. Candid photography had crawled out of its high chair… and onto the street.

Today or yesterday, this is about more than just technical advancement. The unspoken classism of photography has always been: people with money get great cameras; people without money can make do. Sure, early breakthroughs like the Ermanox made it possible for anyone to take great low-light shots, but at $190.65 in 1920’s dollars, it wasn’t going to be used at most folks’ family picnics. Now, however, that is changing. The walls between “high end” and “entry level” are dissolving. More technical democracy is creeping into the marketplace everyday, and being able to harness available light affordably is a big part of leveling the playing field.

So, lots more of us can feel like a kid with a new toy, er, lens.

Related articles

- Prime Lenses (nikonusa.com)

- Understanding Focal Length (nikonusa.com)

TURNING UP THE MAGIC

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CHRISTMAS IS SO BIG THAT IT CAN AFFORD TO GO SMALL. Photographers can, of course, tackle the huge themes….cavernous rooms bursting with gifts, sprawling trees crowning massive plazas, the lengthy curve and contour of snowy lanes and rustic rinks…..there are plenty of vistas of, well, plenty. However, to get to human scale on this most superhuman of experiences, you have to shrink the frame, tighten the focus to intimate details, go to the tiny core of emotion and memory. Those things are measured in inches, in the minute wonder of things that bear the names little, miniature, precious.

And, as in every other aspect of holiday photography, light, and its successful manipulation, seals the deal.

A proud regiment of nutcrackers, made a little more enchanting by turning off the room light and relying on tiny twinklers. 1/2 sec., f/4, ISO 100, 20mm

In recent years I have turned away from big rooms and large tableaux for the small stories that emanate from close examination of corners and crannies. The special ornament. The tiny keepsake. The magic that reveals itself only after we slow down, quiet down, and zoom in. In effect, you have to get close enough to read the “Rosebud” on the sled.

Through one life path and another, I have not been “home” (that is, my parents’ home) for Christmas for many years now. This year, I broke the pattern to visit early in December, where the airfare was affordable, the overall scene was less hectic and the look of the season was visually quiet, if no less personal. It became, for me, a way to ease back into the holidays as an experience that I’d laid aside for a long time.

A measured re-entry.

I wanted to eschew big rooms and super-sized layouts to concentrate on things within things, parts of the scene. That also went for the light, which needed to be simpler, smaller, just enough. Two things in my parents’ house drew me in: several select branches of the family tree, and one small part of my mother’s amazing collection of nutcrackers. In both cases, I had tried to shoot in both daylight and general night-time room light. In both cases, I needed some elusive tool for enhancement of detail, some way to highlight texture on a very muted scale.

Call it turning up the magic.

Use of low-power, local light instead of general room ambience enhances detail in tiny objects, revealing their textures. 1/2 sec., f/4, ISO 100, 20mm.

As it turned out, both subjects were flanked by white mini-lights, the tree lit exclusively by white, the nutcrackers assembled on a bed of green with the lights woven into the greenery. The short-throw range of these lights was going to be all I would need, or want. All that was required was to set up on a tripod so that exposures of anywhere from one to three seconds would coax color bounces and delicate shadows out of the darkness, as well as keeping ISO to an absolute minimum. In the case of the nutcrackers, the varnished finish of many of the figures, in this process, would shine like porcelain. For many of the tree ornaments, the looks of wood, foil, glitter, and fabric were magnified by the close-at-hand, mild light. Controlled exposures also kept the lights from “burning in” and washing out as well, so there was really no down side to using them exclusively.

Best thing? Whole project, from start to finish, took mere minutes, with dozens of shots and editing choices yielded before anyone else in the room could miss me.

And, since I’d been away for a while, that, along with starting a new tradition of seeing, was a good thing.

Ho.

Related articles

- How to Take a Picture of Your Christmas Tree (purdueavenue.com)

DREAMS DOWN TO DUST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT WAS, ON ONE LEVEL, A COMPLETE WASTE OF GASOLINE: a half-hour’s drive to a dusty cluster of tables scattered across a vacant lot in Carefree, Arizona; a gathering of junk gypsies, hunkering for shade under their teepee nation of display tents, their sprawls of pre-owned debris bunched onto card tables filled with the remains of people’s lives. It was going to take exactly five minutes to make one sad pass around this serpentine mound of resale refuse. No treasures today. Maybe we have time to catch lunch before we drive back to town.

These strange mash-ups of godforsaken bric-a-brac are common in many of the small towns of the southwest. Sometimes they are found shoehorned into sagging old adobe buildings on their umpteenth re-use. Other times they are charitably called “swap meets” or “vintage sales” and litter the parking lots of down-and-out drive-in theatres like the aftermath of an air crash. The visual impact is always the same, that of an attic that has been dynamited to bits, then shoveled into milk cartons and slapped with improvised glo-orange price tags. Coffee cans filled with unrelated fragments of trinkets; cardboard cartons overflowing with random chunks of household backfill. Two mysteries pervade: where has all of this come from….and where can it possibly be heading?

I was about one minute away from the end of my doleful tour when I spotted this box, which someone had filled with mis-matched bits of small dolls. One of such souvenirs on a big table makes no visual impression whatever, but a mass of them together is some kind of little minor-key symphony of dreams gone down to dust. Loved objects that were once transformed into the stuff of fancy, now just shards of lives dumped into a cigar box. I risked one picture. For some reason it haunts me.

But see what you think.

It isn’t about what we look at but what we see.

We leave such a colossal wake of trash behind us as our lives thunder and crash through the world. How to sort out all the stories inside?

SUM OF THE PARTS

No one home? On the contrary: the essence of everyone who has ever sat in this room still seems to inhabit it. 1/25 sec., f/5.6, ISO 320, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ANNIE LIEBOVITZ, ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST INNOVATIVE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHERS, people are always more than they seem on the surface, or at least the surface that’s offered up for public consumption. Her images manage to reveal new elements in the world’s most familiar faces. But how do you capture the essence of a subject that can’t sit for you because they are no longer around…literally? Her recent project and book, Pilgrimage, eloquently creates photographic remembrances of essential American figures from Lincoln to Emerson, Thoreau to Darwin, by making images of the houses and estates in which they lived, the personal objects they owned or touched, the physical echo of their having been alive. It is a daring and somewhat spiritual project, and one which has got me to thinking about compositions that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Believing as I do that houses really do retain the imprint of the people who lived in them, I was mesmerized by the images in Pilgrimage, and have never been able to see a house the same way since. We don’t all have access to the room where Virginia Woolf wrote, the box of art chalks used by Georgia O’ Keefe, or Ansel Adams’ final workshop, but we can examine the homes of those we know with fresh eyes, finding that they reveal something about their owners beyond the snaps we have of the people who inhabit them. The accumulations, the treasures, the keepings of decades of living are quiet but eloquent testimony to the way we build up our lives in houses day by day, scrap by personal scrap. In some way they may say more about us than a picture of us sitting on the couch might. At least it’s another way of seeing, and photography is about finding as many of those ways as possible.

I spent some time recently in a marvelous old brownstone that has already housed generations of owners, a structure which has a life rhythm all its own. Gazing out its windows, I imagined how many sunrises and sunsets had been framed before the eyes of its tenants. Peering out at the gardens, I was in some way one with all of them. I knew nothing about most of them, and yet I knew the house had created the same delight for all of us. Using available light only, I tried to let the building reveal itself without any extra “noise” or “help” from me. It made the house’s voice louder, clearer.

We all live in, or near, places that have the power to speak, locations where energy and people show us the sum of all the parts of a life.

Thoughts?

A BLOCK OF THE MILE

The building that originally housed Desmond’s department store, and one of the mostly intact survivors of a golden age of Art Deco along Los Angeles’ historic “Miracle Mile”.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CALIFORNIA’S CITIES, FOR STUDENTS OF DESIGN, contain the country’s largest trove of Art Deco, the strange mixture of product packaging, graphics, and architectural ornamentation that left its mark on most urban centers in America between 1927 and the beginning of World War II. The Golden State seems to have a higher concentration of the swirls, chevrons, zigzags and streamlined curves than many of the country’s “fly over” areas, and the urban core of Los Angeles is something like a garden of delights for Deco-dent fans, with stylistic flourishes preserved in both complete buildings and fragmented trim accents on business centers that have been re-purposed, blighted, re-discovered, resurrected or just plain neglected as the 20th century became the 21st. And within that city’s core (stay with me) the up-again-down-again district once dubbed the “Miracle Mile”, centered along Wilshire Boulevard, remains a bounteous feast of Deco splendor (or squalor, depending on your viewpoint).

CALIFORNIA’S CITIES, FOR STUDENTS OF DESIGN, contain the country’s largest trove of Art Deco, the strange mixture of product packaging, graphics, and architectural ornamentation that left its mark on most urban centers in America between 1927 and the beginning of World War II. The Golden State seems to have a higher concentration of the swirls, chevrons, zigzags and streamlined curves than many of the country’s “fly over” areas, and the urban core of Los Angeles is something like a garden of delights for Deco-dent fans, with stylistic flourishes preserved in both complete buildings and fragmented trim accents on business centers that have been re-purposed, blighted, re-discovered, resurrected or just plain neglected as the 20th century became the 21st. And within that city’s core (stay with me) the up-again-down-again district once dubbed the “Miracle Mile”, centered along Wilshire Boulevard, remains a bounteous feast of Deco splendor (or squalor, depending on your viewpoint).

The Miracle Mile was born out of the visionary schemes of developer A. W. Ross, who, in the 1920’s, dreamed of drawing retail dollars to an area covered in farm fields and connected only tentatively to downtown L.A. by the old “red car” trolley line and the first privately owned automobiles. Ignoring dire warnings that the creation of a massive new business district in what was considered the boondocks was financial suicide, Ross pressed ahead, and, in fact, became one of the first major developers in the area to design his project for the needs of passing car traffic. Building features, display windows, lines of sight and signage were all crafted to appeal to an auto going down the streets at about thirty miles per hour. As a matter of pure coincidence, the Mile’s businesses, banks, restaurants and attractions were also all being built just as the Art Deco movement was in its ascendancy, resulting in a dense concentration of that style in the space of just a few square miles.

The period-perfect marquee for the legendary El Rey Theatre, formerly a movie house and now a live-performance venue.

It was my interest in vintage theatres from the period that made the historic El Rey movie house, near the corner of Wilshire and Dunsmuir Avenue, my first major discovery in the area. With its curlicue neon marquee, colorful vestibule flooring and chromed ticket booth, the El Rey is a fairly intact survivor of the era, having made the transition from movie house to live-performance venue. And, as with most buildings in the neighborhood, photographs of it can be made which smooth over the wrinkles and crinkles of age to present an idealized view of the Mile as it was.

But that’s only the beginning.

On the same block, directly across the street, is another nearly complete reminder of the Mile’s majesty, where, at 5514 Wilshire, the stylish Desmond’s department store rose in 1929 as a central tower flanked by two rounded wings, each featuring enormous showcase windows. With its molded concrete columns (which resemble abstract drawn draperies), its elaborate street-entrance friezes and grilles, and the waves and zigzags that cap its upper features, the Desmond had endured the Mile’s post 1950’s decline and worse, surviving to the present day as host to a Fed Ex store and a few scattered leases. At this writing, a new owner has announced plans to re-create the complex’s glory as a luxury apartment building.

The details found in various other images in this post are also from the same one-block radius of the Wilshire portion of the Mile. Some of them frame retail stores that bear little connection to their original purpose. All serve as survivor scars of an urban district that is on the bounce in recent years, as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (installed in a former bank building), the La Brea Tar Pits, and other attractions along the Mile, now dubbed “Museum Row”, have brought in a new age of enhanced land value, higher rents and business restarts to the area. Everything old is new again.

The Wilshire Boulevard entrance to Desmond’s, with its period friezes, ornate grillwork and curved showcases intact.

Ironically, the district that A.W. Ross designed for viewing from behind the wheel of a car now rewards the eye of the urban walker, as the neighborhoods of the Miracle Mile come alive with commerce and are brought back to life as a true pedestrian landscape. Walk a block or two of the Mile if you get a chance. The ghosts are leaving, and in their place you can hear a beating heart.

Suggested reading: DECO LAndmarks: Art Deco Gems of Los Angeles, by Arnold Schwartzman, Chronicle Books, 2005.

Suggested video link: Desmond’s Department Store http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJj3vxAqPtA

BOXFULS OF HISTORY

Once, these objects were among the most important in our daily lives. Seen anew after becoming lost in time, they show a new truth to our eyes. 1/60 sec., f/4.5, ISO 100, 30mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE DAYS WHEN THERE IS NOTHING TO SHOOT, or so it seems. The “sexy” projects are all out of reach, the cool locales are too far away, or the familiar themes seem exhausted. Indolence makes the camera feels like it weighs thirty pounds, and, in our creative doldrums, just the thought of lifting it into service seems daunting. These dead spots in our vision can come between projects, or reflect our own short-sighted belief that all the great pictures have already been made. Why bother?

“Time is wasting”… but need not be wasted. Find the small stories of lost objects lurking in your junk drawers. 1/30 sec., f/2.8, ISO 200, 7.9mm.

And yet, in most people’s immediate circle of life there are literally boxfuls of history …..the debris of time, the residue of the daily routines we no longer observe. In Raiders Of The Lost Ark, the villain Rene Belloq makes the observation that everything can be an archaeological find:

Look at this pocket watch. It’s worthless. Ten dollars from a vendor in the street. But I take it, I bury it in the sand for a thousand years, and it becomes priceless.

Subjects ripe for still lifes abound in our junk drawers, in the mounds of memorabilia that our loving friends or spouses dreamily wish we would give to the Goodwill. Once ordinary, they have been made into curiosities by having been taken out of the timeline. In many ways, our camera is acting as we did when we first beheld them. And getting to see something familiar in a new way is photography’s greatest gift, a creative muscle we should all be seeking to flex.

Call it “seeing practice.”

Ordinary things are no longer ordinary once they are removed from daily use. Their context is lost and we are free to judge them as we cannot when they are part of the invisible fabric of daily habit. For example, how ordinary are those old piles of 45-rpm records on which we no longer drop a needle? Several revolutions in sound later, they no longer provide the same aural buzz they once did, and yet they still offer something special in the visual sense. The bright colors and bold designs that the record labels used to grab the attention of music-crazed teenagers in the youth-heavy ’60’s are now vanished in a world that first made all “records” into bland silver-colored CDs and then abolished the physical form of the record altogether. They are little billboards for the companies that packaged up our favorite hits; there is no “art” message on most of the sleeves, as there would have been on album covers. They are pure, unsentimental marketing, but the discs they contain are now a chronicle of who we were and what we thought was important, purchases which now, at the remove of half a century, allow us to make a picture, to interpret or re-learn something we once gave no thought to at all.

Old trading cards, obsolete clothing, trinkets, souvenirs, heirlooms….our houses are brimming with things to be looked at with a different eye. There is always a picture to be made somewhere in our lives. And that means that many of the things we thought of as gone are ready to be here, again, now. Present in the moment, as our eyes always need to be.

The idea of “re-purposing” was an everyday feat for photographers 150 years before recycling hit its stride. Everything our natural and mechanical eyes see is fit for a second, or third, or an infinite number of imaginings.

Your crib is bulging with stories.

All the tales need is a teller.

Thoughts?