OF SECOND THOUGHTS AND POSTSCRIPTS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WOULD LOVE TO BE ONE THE FEW MIRACULOUSLY GIFTED PHOTOGRAPHERS who can perfectly and consistently frame and expose an image S.O.O.C. (straight out of the camera). But I am not one of those people. I do my best to come as close to that ideal as possible, pre-planning shots and executing them as near to that vision as I can. I produce a great many usable pictures, first drafts if you will, to which I then apply the absolute minimum of monkeying after the fact. But, nearly always, my best pictures are collabs between what I shot and what I later discovered would best augment those shots. Thus the Holy Grail of S.O.O.C., a near religion for many, raises a lot of issues for me.

It doesn’t take long before the hope that one can shoot a picture that is so complete, so fully realized in its original conception, becomes the primary reason for making or judging a picture. This, to me, equates to a kid coloring perfectly within the lines, obeying all the rules about how to apply the right amount of crayon here or there. A certain sterility can set in, where the main object is merely to be able to boast that what you see is virginal, untouched by even well-intentioned human hands. That, in turn, can lead to mediocrity, or worse for a photographer, inflexibility.

What one person might call a manipulation, i.e., an offense against purity, is, to others, merely the second or third phase of taking a generally usable photo and helping it become great…..in perfecting the composition, in boosting the dramatic power of something that was essentially delivered, but understated, in the original. The S.O.O.C. shot you see up top here is, for a quick snap, very close to what I saw in my mind’s eye. However, the simple crop shown above gives the surging surf above the boy more immediacy, tweaking up the tension between him and the sea. I also committed the additional desecration of amping the ocean’s blueness and the contrast in the boy’s reflection. Did I rescue the picture, or ruin it? And, bear in mind that I’ve described very fundamental interventions, even though all of them are enough to scandalize the S.O.O.C. crowd. Well, tough…..

Photography is a living thing, and hopefully our best results will also seem alive. But just as painters re-do entire sections of a canvas from a sunset to a profile on their way to a final masterpiece, shooters must be free to use a second (or third) pass on an image, rather than relying on the snap of the shutter to reliably deliver miracles on demand. A two-putt is not as spectacular as a hole-in-one, but it still looks pretty damned good on a scorecard.

MY MAINTENANCE YEAR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NOT ALL PROGRESS IS MEASURED MERELY IN FORWARD MOTION. The phrase “look how far we’ve come” is regularly used to indicated growth, when, in photography, as in many other ventures, the sentence “look how wide/deep we’ve expanded” may be just as important. Thus, at the close of a year such as the one I’ve just survived, my work with images isn’t best seen as a series of break-throughs or epiphanies as an attempt to refine or improve the existing areas of my knowledge that could use a good buffing-up.

The Skirball Cultural Center’s salute to the American Immigration experience, Los Angeles, 2025.

I came to this conclusion after reviewing the calendar year and finding few, if any, miraculously fresh things in the “done” basket, just more detailed ways of delivering the ideas I’ve already explored over many years. Part of this was my own compromised health, which, though temporary, definitely kept me in Emily Dickinson mode, confined to the house and dreaming of the picture opportunities left untouched just outside my window (Emily was a real whiz with a Rollieflex, as I recall). There were too many days I just couldn’t be “out among ’em”, which led me to work, instead, on a deeper dive into things I could work on without a lot of travel.

This led me to a couple of productive areas, including tackling the unexpectedly steep learning curve for a new lens (it takes a lot of work to make things appear effortless, ha), giving me time to enhance my approach to low-light situations (including new uses for Auto-ISO in my wildlife work), and to renew my continuing love affair with 50mm primes. During the times that I was more completely mobile, I found myself searching for visible measures of patriotism, from small marches to grand museum exhibits (see above). In the current season, it seemed only natural to turn my camera toward one of the most convulsive societal upheavals in my seventy-plus years on the planet, and, when I was more regularly out-of-doors, I made a special effort to capture that tension in-camera. As I said, this was a year of sinking deeper taproots into things I needed to improve rather than boldly going where no one has gone before, and I am trying to tell myself that that, too, is of value. Or so I hope.

CLICKING WITH THE LADIES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

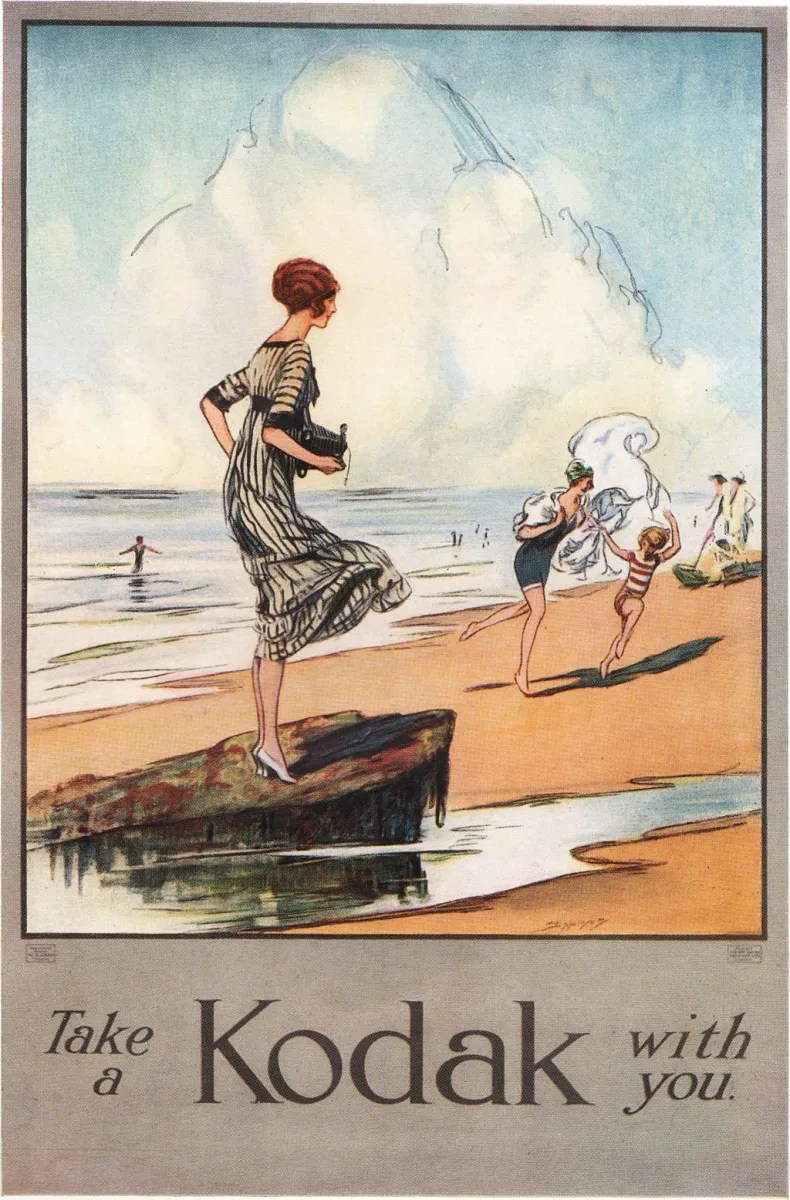

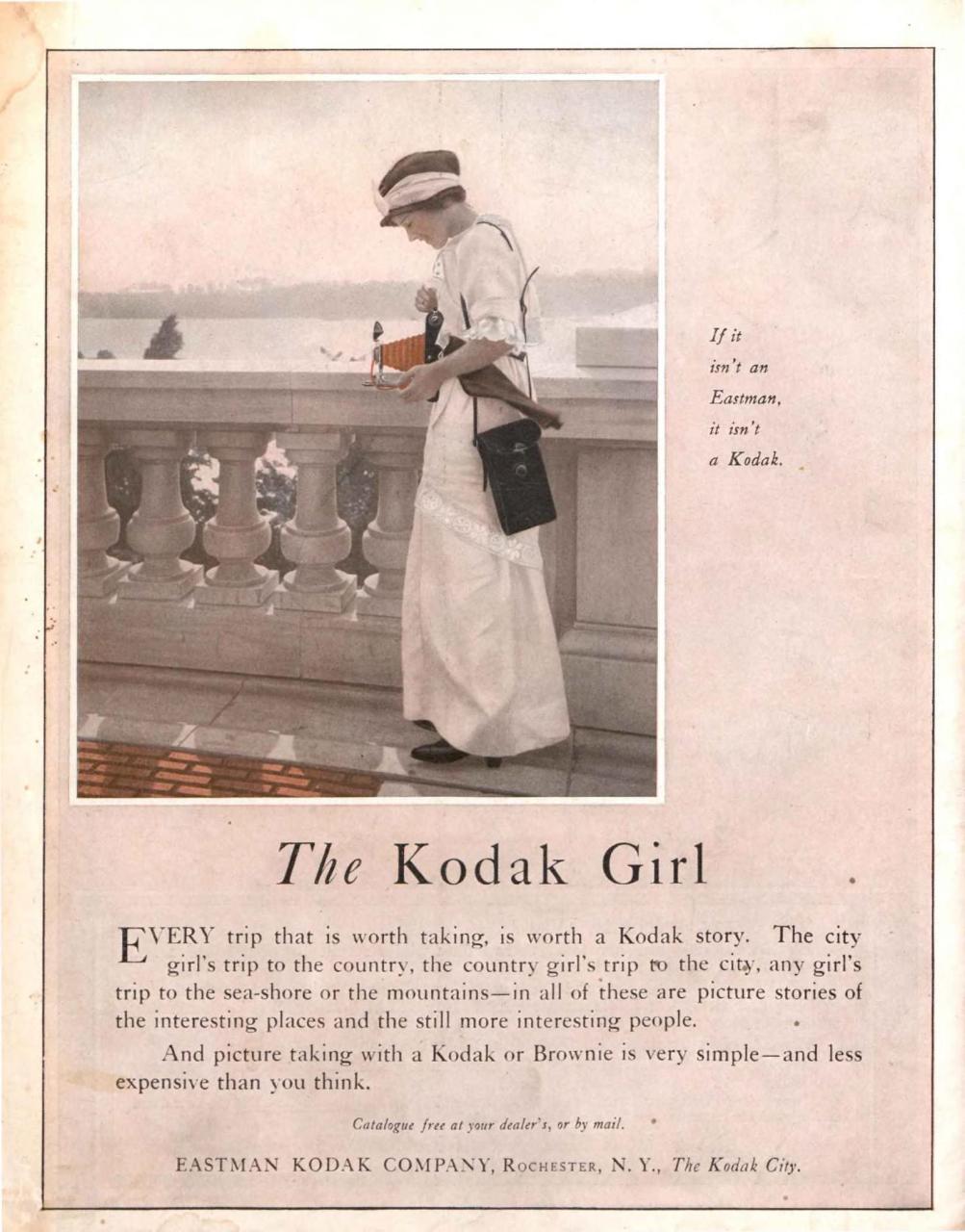

NO ONE ALIVE TODAY CAN RECALL A WORLD in which a camera of some kind was not considered an essential personal accessory, especially after the recent iPhone revolution has absolutely completed the “democratization” of photography. That concept, the idea that everyone should own a camera and take it everywhere, was, at one time, a novel idea, a behavior that had to be taught. And, as in so many cases with early amateur photography, the teacher for that habit was the Eastman Kodak Company.

Having already made cameras cheap and simple to operate by the end of the 19th century, the company next tackled the task of making people want to use them, and use them all the time. Kodak was certainly a “hardware” company, in that they made a wide line of cameras, but their bread and butter was as a “software” company, as it was the sale of Kodak film that created its biggest profit. And so, having provided the means for taking a lot of pictures, they turned to engineering the desire to do so, especially as regarded female consumers, where they saw their biggest potential growth.

Enter the Kodak Girl.

Young, adventurous, jaunty, and constantly pictured with a Kodak at the ready, The Kodak Girl was first featured in prominent women’s magazines in the late 1800’s, ready to preserve key moments at parks, the beach, and the mountains, as well as capturing key moments around the home. She was shown in a variety of poses and styles so as to appeal to both the stay-at-home mother and the active seeker, but her greatest role was as The Closer, a character with which consumers could easily identify, sparking their own decisions to buy their first personal camera and make its constant use a regular activity. Kodak kept evolving the Girl’s physical look as the 20th-century saw women gain in spending power as well as personal empowerment, modeling some ads in the ’20’s after silent screen actress Edith Johnson. Decades later, they would refresh the old campaign yet again, dubbing a young bathing beauty named Cybil Shepherd as a Kodak Girl for the age of Aquarius.

Thus, Kodak pioneered the idea of putting a camera in everyone’s hand a century before Steve Jobs added his own variation to the campaign, his iPhone removing the last real barrier to universal camera use. Introducing a truly useful thing into the world is a great talent, but the ability to convince people they need something they’ve never even thought to wish for is an equally remarkable skill.

THE JOLLY’S IN THE DETAILS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS A FIRST-TIME READER OF A CHRISTMAS CAROL (I believe I was eleven), I recall being deeply touched by Charles Dickens’ poignant description of Mrs. Bob Cratchit, busying herself with the preparation of the poor family’s meager holiday feast, and doing her best to maintain simple dignity with re-sewn clothing and modest adornments, or as he put it:

“dressed out but poorly in a twice-turned gown, but brave in ribbons, which are cheap and make a goodly show for sixpence.”

The passage shaped me, with the idea that, in contrast to the grand shop windows, the magnificent parades and the brightly blazing light displays, most people have what the popular song refer to as a “Merry Little Christmas”, an observance measured not by the yard, but, like Mrs. Cratchit’s ribbons, by the inch. Many of us live with holidays that are simple, stretched thin, re-used, brave. This feeling informed my view about a year after reading Carol, as I pointed my first primitive camera at seasonal celebrations in my little neighborhood. Always, it was the small signs, the homemade cheer, the quiet grace notes of people’s celebrations that interested me most. To this day, a house swallowed in 40,000 blazing watts of flying reindeers and dancing snowmen is far less appealing to me than a single candle mounted in a window that looks like it seldom houses anything like joy.

Even the song Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas itself, introduced in WWII’s days of separation and longing, is not really about celebration; it’s about making it through, about believing that the very next Christmas will be the one that pays off for all of us, if we’re patient. To this day, I love making pictures out of people’s make-do holidays. The small stuff counts for even more when you gain the perspective of a long life. What to hope for? Certainly not just “more of” or “bigger than”, but, instead, a wish that, like Mrs. C., even if all we have to mark the glad occasion are new six-pence ribbons, we can at least appear brave in them.

SLOW THE F(stop) DOWN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVER SINCE PHOTOGRAPHY SPLIT INTO TWO VERY DISTINCT CAMPS, the pro-digital and the pro-film, I have been constantly evaluating the claims and, indeed, the motivations of both factions. At one time, I must admit that, even though I myself was weaned on film, the analog-forever crowd struck me as a little superior, as if the choice of that medium alone put their work on a higher plane. And, of course, the digital gang could also be guilty of being dismissive of any tech before 2,000 as retrograde and primitive. Both sides had their extremely loud champions, and both were guilty of short-sided priggishness as regarded the other.

Only one way to get this shot under these conditions, and that’s to slow down for a :30 exposure.

Over time, as predominantly digital as I am, I have grown fond of many of the the film folks’ return to nearly all-manual calculation of their shots. In short, in a digital world, where immediate gratification and a blizzard of volume define many people’s shooting regimens, the filmies have very purposefully opted for shooting in a manner that demands that they slow the f down. The deliberation required to shoot film forces the discipline of patience upon the shooter, retarding his pace to the point where certain qualitative questions become, as they were in the analog era, clearly visible. For example, in a medium where you are working with a limited number of opportunities (exposures), you can easily find yourself asking, Do I need this picture? and the corollary Is this the time/are these the conditions for taking it? In a world of restricted choices and the slower pace required to execute a shot precisely, it’s not unreasonable to feel a greater sense of intentionality, which is required for compelling images in any medium.

Of course, you can impose this discipline on yourself in a digital medium, although it takes much more concentration and practice to learn/unlearn all the habits associated with quick results. Slowing down to the point where you can clearly see where the spaces between the points of a technique lie, and how they link to each other for a good result, adds to one’s understanding, creating a more distinct difference between decision and habit, or craft and art. Speed is indeed seductive, but, as in many other aspects of life, it’s a short cut, and, as we all know, some short cuts lead to blind alleys.

THE LAND OF NO EXCUSES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

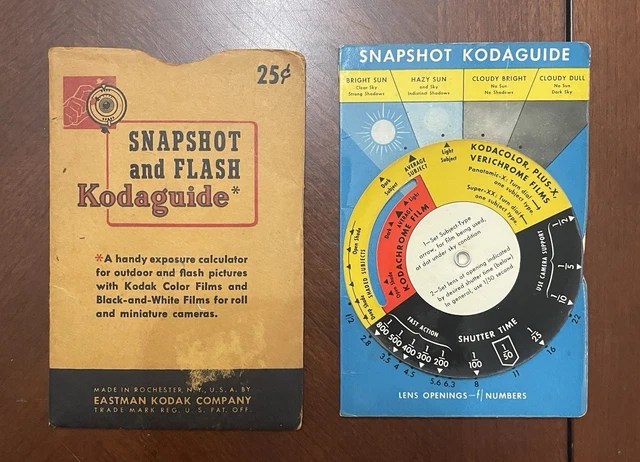

THE TIME IS FAST APPROACHING where most of the photographers in the world will have no personal memory of just how much technical skill once needed to be applied just to obtain a usable photograph. We are already a full generation removed from a world in which film had to be purchased, loaded, exposed, unloaded and processed before the results could be viewed. Also gone for most people is the careful budgeting of shots that had to be plotted so that snaps of a vacation could be captured within the span of 24 or 36 exposures, rather than the endless barrage of shots made typical in the digital age. And beyond all that lies an additional plethora of calculations, tools, aides, and attachments once enlisted in the great effort expended in making pictures look, well, effortless. These all speak not to the art but to the craft of photography, and, as they fade away for good, all we are left with is endless possibilities and greatly increased responsibility. Simply put, there is almost no excuse for making a bad image.

The little wonder you see here was produced by Eastman Kodak Company for generations, and was always tucked into my father’s shirt pocket for quick consultation before triggering the shutter. For shooters of his generation, taking a shot meant first solving a math problem. Composition and inspiration came in second or third after just being able to hack the science of it all. Many cameras had basic instructions for use or loading inscribed inside their covers, and every roll of film was accompanied by a flier on how to correctly expose that particular emulsion. The aforementioned Kodak also kept HOW TO MAKE GOOD PICTURES, its basic primer on photo techniques, in print for nearly sixty years. And then you also factor in the efforts of the true purists, those who chose to process their own film. The point is, the apparatus involved in being able to take the uncertainty out of photography is largely gone, with more responsive “serious” cameras and mobiles virtually guaranteeing a workable result every single time.

So why are there still so many awful, bland, uninteresting, insanely misconceived photos? Well, it could be because there is still a real limit to what cameras can do. Granted, they are better than ever at anticipating what we need in a given situation and trying to supply it. They are also incredible at protecting us against our own limited skills. But they cannot think. Or feel. Or, to be very hippy-dippy, dream. The best photographers are, in fact, dreamers, and it was not so long ago that our dreams were thwarted, or at least compromised, by our need to “master” the camera, to tame it as one might a wild stallion. Now, we no longer have to fight our gear to a draw. The craft aspect is largely gone. The art part remains. And that’s on us.

STREAMING KILLED THE THEATRE STAR?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS YOU READ THIS, ANYONE WITH A KEYBOARD AND THE MINUTEST CONNECTION TO THE ENTERTAINMENT BIZ is crapping bricks over the sale of Warner Brothers to yet another new owner, (of which there have been more than a dozen), regarding said merger/sale as the death knell for theatrical movies in the Golden Age Of Streaming. This mass panic ignores the fact that “going to the movies”, as a regular practice, has been heading for Dodo-land for decades, and that, sorry folks, but things change and evolve. We will always love storytelling, but we will constantly be revising the delivery system we choose to use. Ask the 1920’s studio heads that predicted that “talkies” were a passing fad.

For me, the major sensory delight of going out to a film has been gone for some time, being intertwined as it was with the atmosphere engineered into the theaters built in the first third of the 1900’s. The over-the-top grandiloquence, the overkill raised to a the status of a science, immersed the moviegoer in rich fantasy worlds that provided vivid escape even before the curtain went up (yes, Virginia, there were curtains) and the overture began (and, yes, Virginia, there were overtures, as well). We had a deep, profound crush on the places where movies were shown, a crush that was trampled underfoot in the back half of the twentieth century, as those miraculous movie palaces were replaced with bland boxes, mere assembly halls equipped with projectors. They were certainly places we went to see movies, but they ceased to be…. theaters.

I live near Los Angeles now, and being a frequent day-trip visitor, I have inherited a plethora of dozens of grand old movie houses that, in the town that perfected make-believe, have been allowed to age into the 2000’s, repurposed either as subdivided multi-screen complexes, playhouses, or live performance venues. It’s the kind of legacy that has long since vanished from much of the heartland, and, as a photographer, I get a little drunk with power at the chance to walk their halls and document their dreamscapes. The images here are from a medium-sized 1930 cinema called the Saban, which hosts any and every kind of entertainment event at its original location on Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills. I love movies, and I always will. I also used to love where I went to love movies. Now, late in the game, I have more chances than ever to leaf through the scrapbook of that romance. Mergers be damned, it really wasn’t streaming that killed the theatre star; that particular murder has a hundred different authors.

DRIBS & DRABS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHIC COMPOSITION IS A CONSTANT YIN-YANG OF ADDITION AND SUBTRACTION, an ongoing argument over what, indeed, is essential for the narrative of an image. Sometimes, as in the case of a vast, sprawling vista, wide and inclusive is the best choice. Under other circumstances, huge chunks of that same vista can be sliced away to amplify the importance of some smaller thing happening in the larger panorama. Most of us do this either-oring almost without thinking, often trusting our first instinct on what should be included or excluded in a particular case. And sometimes, the answer to the question “how much info is enough?” comes to us later, upon repeated reviews of pictures we thought were, well, perfect.

I love shooting huge subjects as wide as I can, but, upon review, I find that they speak more persuasively if I judiciously remove areas that, on first look, can seem essential. But essential for what? In trying to tell a story, you can either immerse yourself in rich detail or try to suggest more by showing less, or, more precisely, in telling as much story with the simplest visual cues you can.

The shot you see here was taken on a beach in San Simeon, California. It is a protected refuge for baby elephant seals, who crawl on the sand and help themself to the healing combo of sunshine and sleep. They crowd the sands by the hundreds, much to the delight of passerby who often travel hundreds of miles just to watch the oversized infants chill out. I have plenty of pictures of this scene that take in the entire beach, focus on a sea of whiskery, sandy snouts, or show the seals in the context of the surrounding coastline.

But here, I just wanted a tight shot of one seal’s limp flipper, no more, no less. It’s an exercise in seeing if I can suggest all that bigger stuff I just mentioned in something close at hand. In fact, the shot you see here is a crop of a crop of a crop, as I kept paring away any dribs and drabs that could compromise the one, single thought that I wanted to convey. It’s also a reminder (one that I need on a regular basis) that the best stories are often the simplest. Sometimes, they happen in a vast forest. And sometimes they are seen in the veins of a single leaf.

20 x 50=31

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM STILL RETRENCHING AND REFRESHING AFTER A FIRST YEAR IN CALIFORNIA which saw me using full auto to a far greater degree than is normal for me. In this honeymoon phase, sensory overload was the word of the day, with new places and experiences cascading with such speed that I found myself shooting reactively, hoping, in many cases, that some of the snaps I took in haste would later be re-done with a finer degree of control. My prescription for this feeling that the process was doing me, instead of the reverse, was to retreat into fully manual work for at least my non-wildlife stuff. This meant re-acquainting myself with the lens that served as the foundation for most of my earliest writings in THE NORMAL EYE some fourteen years ago, a 50mm f/2.

There is something to be said for taking full responsibility for your shots and for using what serves many as “the only lens I need”, regardless of the setting or situation. The more stringent rules of engagement, from framing to exposure calculation to focus, actually work to free a photographer, in that he always knows what to expect of the lens, both in its limitations and its ease and simplicity of operation. The so-called “nifty fifty” is cited by many shooters as not only their go-to, but their entire kit. And for this year, I wanted to investigate some of he best third-party 50’s from the late analog era, 1975-1985 mostly.

A Pentax-M 50mm f/2, built from 1975-1982, adapted for use on a Nikon Z5 body for under $40.

For years, I had stayed on Team Nikon, using an f/1.8 50 manufactured in the late seventies. It was my sole companion for an entire year, comprising much of the work I collected into a book bearing this blog’s name. This year, I had a light-bulb moment and robbed the 50 off the front of my old Minolta SRT-100, truly shooting for free. More recently, after borrowing an old Leica Summicron f/2 from a buddy and driving it around the neighborhood, I became curious about which other 50mm primes from the period would nearly perform as well for less cash, like a lot less. 50’s of every brand were produced in the millions in the late 20th century, being the default kit lens for many models, and are, therefore, the very definition of cheap thrills. Enter the Pentax-M Asahi f/2 seen here (similar to the lenses used by the Beatles on their first cameras, way back in 1964), which I harvested off the internet for 20 dollars American.

And so, with renewed vigor, I’ve decided to shoot everything, not for a year, but at least for the 31 says of December 2025, with just this puppy. It is sharp and light, even with the $15 dumb adaptor that allows it to be mounted to my Nikon Z5. The lens does not share information with the body, but that’s what I am for, supposedly. Let me be honest; I love many auto features. I sometimes even love when my camera anticipates what I need, even when I don’t know what that is. But sometimes you have to go back to basics and remind yourself how to directly make a picture, armed only with your own native cunning and $20 worth of glass.

A DASH. OR A DOSE. OR A SMIDGE. OR….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I’VE NEVER BEEN ONE OF THOSE RIGID RULEMAKERS who dictate that all photographers must shoot something every single day. To me, that’s like saying that you must make an entry in your journal without fail, each day of the year. Now, while you certainly can do so with either pictures or diaries, the whole idea of publish-or-perish seems arbitrary, even a little anal, and I avoid it like I avoid many other things that start with “always do” or “never do”. That, for me, is just not how art happens.

When it comes to making pictures, I have two kinds of dry spells; self-imposed, due to a lack of ideas or motivation (or both); and imposed from outside, like isolation or illness. Presently, I’m just my way out of a dead space of the second type, caused by a back injury, which had meant rolling through a lot of consecutive days when either the inspiration or my own energy to shoot are in short supply. As stated above, I just can’t commit to the “shoot something every day” mantra, but there does come a point, however many days it takes to get to it, when I feel I have to try something, even if it’s small or stupid. This can include staging still life on my computer desk or tracking morning shadow patterns along a wall. I can’t say that I reap too many miracles on these interim assignments, but they are enough…a dash, a dose, a smidge…just a reminder that I haven’t lost either my touch or my enthusiasm.

Photographers can get spooked during dead spots in their daily regimen. It’s not that we quite fear that we’ll never shoot again, more a feeling that making pictures oils some kind of mental hinge, and that rust can set in fast if we don’t give the thing a regular squirt. Imagine Jack Haley in The Wizard Of Oz freezing in mid-sentence or mid-step, needing a jet of juice to get moving again. And then, just when you think you’re washed up, a western bluebird jumps into range and takes mercy on your stranded soul. Such things fire the imagination, and, once that happens, you’re firmly on the comeback trail.

THE DIVINE’S IN THE DETAILS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“IT HAD THE COOLEST CENTER CONSOLE….”

“REMEMBER THAT AMBER INDIAN HEAD AT THE FRONT OF THE HOOD?”

“THE ASHTRAY. IT WAS ALL CHROME. SO ELEGANT..”

I HAVE PHOTOGRAPHED CLASSIC CARS AT NEARLY EVERY KIND of human gathering, excepting perhaps funerals and coroner’s inquests, and I have come to the conclusion that, while designers labor mightily to create sexy, muscular or lean shapes for the entire outer conception of an automobile, it is in the tiniest touches where the fondest user memories reside. Despite the best efforts of the boys at the drawing boards, many cars tend to look alike, like a lot a lot alike, a problem which is further exacerbated when a particular model becomes so successful that it inspires rafts of imitators. No, for the photographer in me, it’s the features, the add-ons, the ups and extras, that burn brightest in my memory.

I recently discovered a 1948 Plymouth Special Deluxe parked about three blocks from my apartment. It may have made an occasional street appearance here and there in the past, but, in recent weeks, it’s out nearly everyday, even though its owners live across the street and have a garage. Yesterday, I set about to pore over every inch of the monster, and, after a few full-on shots, it again occurred to me that the more delicate fixtures, the trims, the small and elegant accents…in other words, the real emotional bait that snags the buyer in the showroom, was what I wanted most to document.

The ’40’s saw the first head-to-toe use of chrome trim, but on a far more modest scale than the rocket-to-mars fins and grilles of the ’50’s. Still, the accent on cars, even in the first post-war years, was on decoration for its own sake. Most accent items on a car add no real function or performance edge, just coolness, and that’s just jim dandy with me. It’s like a big loop running in my head which explains my affection for something beyond its merely practical value; I love it because I love it because I love it, etc. Creature comforts and pure style determine our attachment to things across our lives far more than their actual function or use. And that makes even the most commonplace ride as pretty as a picture.

NOT MY REMEDY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OKAY, LET’S JUST STIPULATE THAT MOST OF US HAVE A larrrrrrrge photo folder filled with what I call SLAGIATT images. Now, longtime friends of this gazette will recognize that acronym as one of my favorites, this one translating to Seemed Like A Good Idea At The Time. You know what’s in the folder: bold experiments, failed executions, incomplete concepts, impossible tasks…..an “orphans” file for the stuff that didn’t work out, the ones that got away. Maybe you yourself don’t actually have such a folder per se, because the shots that qualified for it went to Delete Purgatory years ago. Whatevs. The fact is that the SLAGIATTs always, always outnumber the Keepers. They worry us, haunt us, like running your tongue over where a lousy tooth was extracted, a tooth that, with a little more flossing, you might have saved.

This right here is a SLAGIATT picture.

In early 2024, I was stricken with a particularly bad patch of sciatica. We’re not talking a mild ache here, but a week-long I may-need-help-getting-to-the-john stretch of agony and sleep deprivation. As it happened, the back end of the bout coincided with my birthday, which I usually mark with a formalized self-portrait, an annual state-of-the-union on my face, and what it does or does not project to the camera. I decided not to skip the ritual, despite how I felt, and thus ground out a few of the most painful pictures I have ever produced. I’m not talking about the physical discomfort involved in sitting for the session, but rather of the dismay I experienced looking at the result. I’m sure I thought, at the time (there’s that phrase again), that showing myself in distress was…..what? Honest? Authentic? Brave?? Maybe I thought, hey, I subject everything else to my camera’s unblinking, indifferent eye, so why not my wracked frame? Well, it might have been good mental therapy(again) at the time, but, looking at the pictures a year and a half later, it’s like looking at home movies of a very bad facelift.

This whole issue wouldn’t be top-of-mind with me if I hadn’t just spent another recent multi-week stretch ouching myself around the house, this time with a pinched nerve. Not quite the same level of grief as the sciatica, but enough that, in the mirror, I see, not a brave, determined soul, but merely a tired, sick whiny-baby who wants to get well, like, yesterday. No selfie is going to make me feel “determined”, or stoic, or courageous, at least not right now. And as for my camera, the only thing that’s keeping me positive at present is daydreaming of the day when I can get back out there and point it at something else. Anything else. That may not be the artistic way of seeing the situation, but there it is. In any event, the whole review has been good for me. Some ideas are so bad that they merit a re-think, and maybe a few reflective fingers of scotch.

THE GREAT DEMOCRATIZER

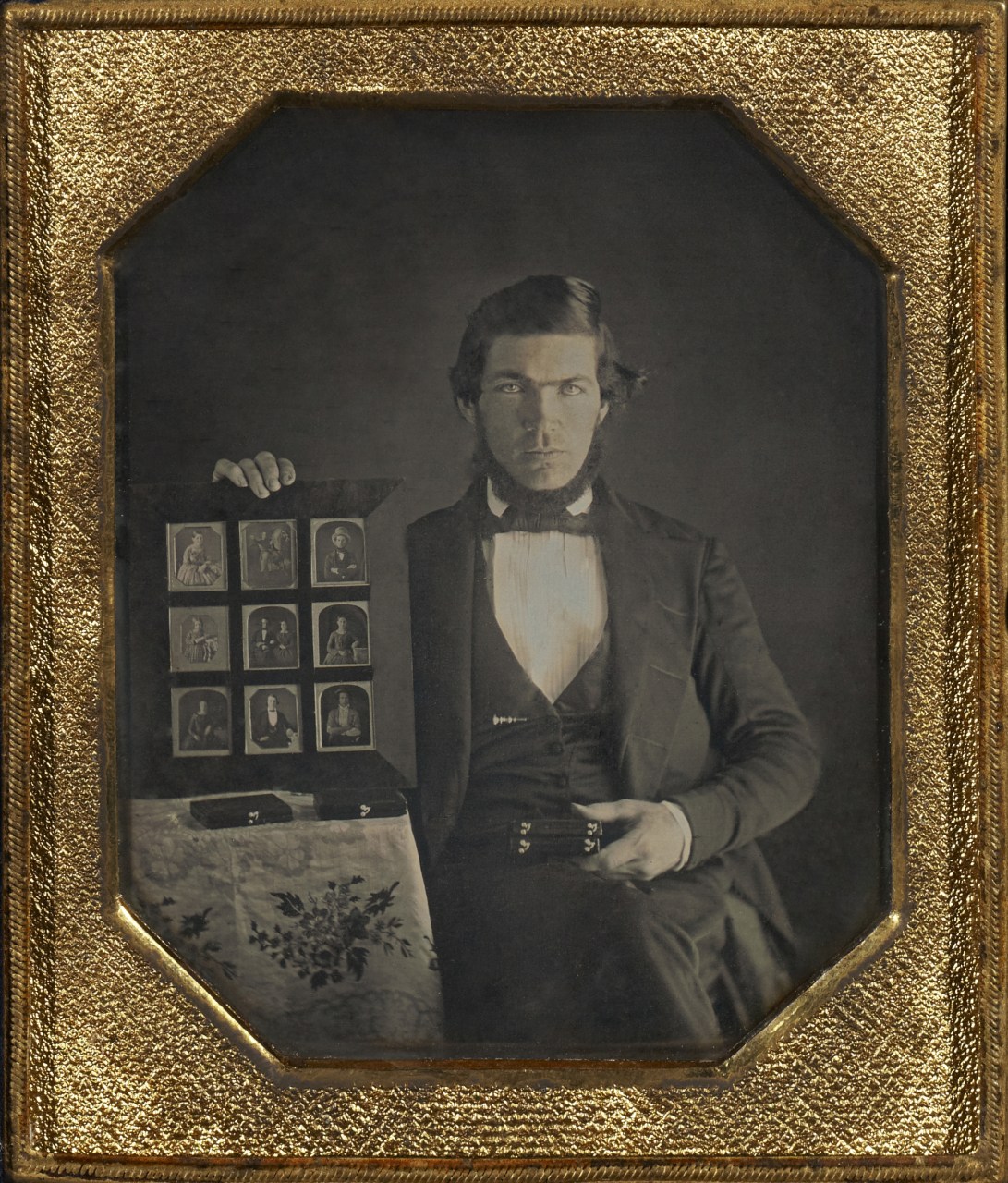

A daguerreotype of a maker of daguerreotypes, and several of his daguerreotypes.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN PHOTOGRAPHY’S FIRST DECADES, THE DAGUERREOTYPE was, for a time, considered the ultimate streamlined process in the making of an image. This direct-positive (that is, no negative) system generated a highly defined image on a sheet of copper with a detail that, centuries later, still impresses…..and so simple to do! Just clean a silver-plated copper sheet and polish it until the surface looks like a mirror. Next, sensitize the plate in a closed box over iodine until it takes on a yellow-rose appearance. Then transfer the plate to a lightproof holder, and transfer the holder into the camera. After exposure to light, the plate is developed over hot mercury until an image appears. The picture is then “fixed” by immersing the plate in a solution of sodium thiosulfate or salt (whichever you have around the house at the time) and then toned with gold chloride. What could be simpler?

A true “snap shot”, taken in haste (out of necessity) but still with some intention.

Small wonder that, by the end of the nineteenth century, when the laborious and hobbynerd-driven practice of photography was suddenly simplified by the introduction of the personal snapshot camera, what had been the domain of artists and tinkerers became the world’s birthright, creating a truly democratized art. Suddenly, photographs were not single or “official” chronicles of things generated by the few, but infinite variants of interpretation wielded by any and everyone. The phrase snap shot, which dates back to the early 1800’s, was originally a term for a hunter who fired from the hip, quickly, and without a lot of deliberate aim or intention. By 1897, the immediacy and ease of making personal pictures saw the first published reference to the taking of a photographic “snap shot”, and the name stuck.

We still use the term to describe the informal or the instinctual, impulse photography that, in the digital age, is easier to indulge than ever. Making images used to be a deliberate, intentional act that required preparation and tortuous practices that could break down or fail at any stage in the process. Now, more than ever, “taking” a picture is as natural as breathing, and yet, the option to slow down, to plan, to sculpt the outcome, to, in effect, intentionally “make” a picture, remains, as photography is an act of both spontaneity and purpose.

WHISPERS IN THE ECHO CHAMBER

Go, go home team!….oh, and by the way, we have a new double feature this week. (Los Angeles, 2025)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOS ANGELES ALMOST SINGLEHANDEDLY INVENTED the fine art of “made you look”, the science of both creating and satisfying pure sensation. That’s why it’s irony-on-steroids that the town is also a tough place in which to….. attract attention.

In a town where the billboard for the latest Fast & Furious epic typically takes up the entire side of a downtown skyscraper and a local mountain range advertises itself with letters the size of a house, the abnormally huge, the Neon Loud, is perpetually being amped up, as what were once obvious appeals to the senses become just more of the visual noise floor. L.A. is the carnival barker gone nuclear, and the images that persist in pop memory are nearly always of the more obvious “titanic”, “colossal”, or “amazing” elements in the mix.

Two guesses what we sell here. (Los Angeles, 2025)

But hang in the smaller neighborhoods; the Venices, the Little Tokyos, the Melroses, and cast your eyes closer to the pavement. See the storefronts. The triple-A contenders for the limited amount of attention that any human passerby can effectively invest. Observe the messaging. Simple. Immediate. Yeah, we’re talking’ to YOU. And instead of the obvious tourist-pic checklist, make pictures instead of the whispers within the city’s vast echo chamber. There, you will not find million-dollar digital graphics, but innovative, even home-made appeals for your eye. Reclaiming old alleys in murals. Blinking in flickery neon over entrances to places simply known as “food” or “eats”. Display windows that must convey, in the moment it takes you to wander past the proprietor’s one-location location, What We Do and Why You Need It.

Hey, we already owned this Jewish deli, so why not paint a whole history of the neighborhood on the side of the building, which needed painting anyway? Los Angeles, 2025

Los Angeles is equal parts poetic and pathetic, vulgar and elegiac, creative and crude. Y’know, like everywhere Angl in America, only more so. More of everything. If they ever manage to get the town in some kind of true “balance”, who knows? It may become as big a yawner as the places we left in order to come here. But for now, live with the weird equilibrium. And before you automatically default your camera eye to the obviously magnificent, train a few frames on the less obviously marvelous.

BLOWING OUT THE PIPES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOME OF MY WORST AND BEST PICTURES share a common bond; their origin usually begins with desperation.

They happen when I’m stalled, knotted-up, stuck. The times when you not only don’t know what the next image will look like, you don’t know if it will even be taken. Hell, you may be done. Poured out, squeezed dry, nothing left to say. Put the cameras in the next neighborhood garage sale and take up, I dunno, knitting.

Written down, this whole sequence of thought seems, well, crazy. And yet, I know that from time to time, something will knock me off course and, for a while, I will just not care if I ever take another picture ever again. It usually occurs as a consequence of a physical injury or illness, the kind of sidelined status where life is boiled down to its absolute essence, when, weighed against photography, makes the pursuit seems trivial, a ridiculous luxury. Earlier this year, in learning how to use a new telephoto lens in the field, I miscalculated how to transfer its nearly six pounds between my two arms, and I pulled some muscle tissue in my right shoulder. We’re talking X-rays, physical therapy, the whole deal, with me stuck with the irony of having waited years to get my hands on this prized toy, only to have it cripple me. I were not thrilled with life.

At this writing, a pinched nerve in my lower back has come along right on the heels of the shoulder, pushing photography even further back into “I can’t deal with this right now”-land and resulting in a week in which I shot virtually nothing. Yesterday, as I watched an impromptu dance mob take form in an arts festival, I knew I had to shoot something. Anything. To remind myself why I was gnashing my teeth from the sidelines. To re-prove to myself that images at least had to be tried. This very strange panorama is the result.

It’s not a great picture. It was available. And it was important for it to be available. Now, while my back hurts. Now, while I’m grouchy and nervous. At the moment, I don’t need home runs. I need to step up and swing at every pitch. Meanwhile, toss this one in the “under consideration” pile, and move on. To anything.

THE BOYS ON THE BEACH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONCE THEY ENTER THEIR TEEN YEARS, many young folk enter a very exclusive photographic club, whose rules dictate that, while they will suddenly become withdrawn or sullen if an adult tries to snap their picture, there is no limit to their enthusiasm for posing ad nauseam for their contemporaries. If their bff points a phone at them, out comes the goofiness and ease. Let a parent make the same move, however, and an iron curtain of blank expressions descends.

I used to think it was just me, since, during my own kids’ adolescence, the questions I received most from the three of them, at the first appearance of a camera, were “really, Dad?” or “again the with camera” or both together. My own children were born too early to come of age in the “always on” era of cel snappers, but they definitely gave their pals a wider berth than myself when it came to striking a pose or showing me their “real face”. Turns out, blood or no blood, they all do it. I mean, I am annoying when armed with a camera, but that’s beside the point.

My wife’s grandsons have now entered the corridor of time in which she has to enact the will of Congress to get them to sit for portraits, suffused with coolness as they are. As the default chronicler for their lives since Day One, I still make the effort, but I work twice as hard rendering them, well, mere components within a composition, as you see here. Getting them to “act natural” when they are enjoying a day at the beach is, well, no day at the beach, and so I merely absorb them into their surroundings, as you see here. And, it’s no concern whether they will like seeing themselves this way, since neither one of them will show any interest in even seeing the results until they reach, say thirty. To get them to care that I even took the picture I would have to be thirteen, female, and cute. I mean, I’m fairly well-preserved, but everyone has their limits.

EDEN OR ABYSS?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHY IS IT ALWAYS THIS WAY?

Why do we always unleash new technologies before we bother to determine whether we need them at all, or whether, used wrongly, they can spell disaster for us?

And yes, I am talking about A.I.’s potential impact on photography. More precisely, I’m expressing a bit of panic, echoed by many, as to what it means for the future of the creative process overall.

Let me confess that, prior to this year, I have not experimented much with A.I. as a post-processing tool. Even now, I have only tried a small handful of “for fun” experiments on my own images. Like many. I am really wrestling with what it means to hand any decisions over on my original work to an entity that largely cannot think by itself, even when acting upon my own directives. The images you see in this post constitute the most dramatic “before” and “after” comparisons I’ve yet mustered, and I must admit that I’m a little, well, frightened.

My apprehension comes from finally seeing one of my images changed, in an instant, from one vision of a subject to a believably rendered version of the opposite of that vision. Beyond novelty, it shows the ability to convincingly re-interpret reality, making the ingredients of my original into a secret “recipe” concocted largely by a non-human that’s learned how to sift through gazillions of actual human works and spit out a reasonable fascimile of what I might have intended myself. That should surely inspire awe as a technical breakthrough, but it also poses an essential creative conundrum; where is the role of the individual in all of this?

Until I can answer that question to my satisfaction, I must treat A.I. photography as both phenomenon and menace. The tech will be a route to either Eden or the Abyss, but every photographer must decide what it means to actually create, and whether he or she will in charge of that decision.

(P.S.—-the second image is the A.I.-generated one.

FUNCTION OVER FORM

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY BEGAN MAINLY AS A MEANS TO DEPICT THINGS, to faithfully document and record. Those things tended to be fairly concrete and familiar; a landscape, a building, a locomotive, portraits, events. Later, when painting freed itself from such strictly defined subject matter, veering into ever more abstract and impressionistic areas, photography, too, found itself exploring patterns and angles that were less “about something”, tableaux that were interesting as pure form.

The industrial age created many installations and factories whose purpose was not clearly obvious at first glance, but as vast collections of pipes, ducts, platforms, and gear that, unlike commercial objects, didn’t at once reveal what their function was. They weren’t contained in stylish cabinets or hidden behind alluring packaging. They just were, and they just did. The arrival of abstract industrial photography was the perfect means for merely admiring the contour and texture of things, without the need for context or explanation. Edward Steichen, Walker Evans and other giants saw and exploited this potential.

That Day At The Plant, 2025

I find myself still drawn to the same aesthetic, as I enjoy walking into complex structures whose use is not immediately obvious. It’s not so much an attempt to imitate those earlier creators of pure form photography as it is to rediscover their joy in the doing. It’s an homage, but it’s also me trying to have a subject affect me in the same way it did for those who went before me. And, of course, with its refusal to use tone to explain or contextualize things, I prefer to do this work in black and white.

In the end, it’s just one more way to look at things, a way to shake up your expectations. You can’t surprise anyone else if you can’t surprise yourself. Forcing yourself to see in new ways, to reconfigure the rules for what a “picture” is, provides stimulation, and that, in turn, invites growth.

DOWN GO THE DOMINOES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THOSE WHO WRITE HISTORIES ON PHOTOGRAPHY understandably see it as an unbroken series of technological breakthroughs that have allowed the art to move forward and gain wider adoption for an ever-growing audience. This leads to an endless litany of Who Did What followed by Who Did What Next followed by What Did It Mean. When I look at the breaking of these barriers, it’s even more personal. Because when something new happens in photography, the net result, for me, is to help me get to the picture-making part with less delay and fewer screwups.

Take the most elementary part of creating an image, i.e., the gathering of light. We make ourselves crazy trying to corral as much of it as quickly as possible with as few intermediary steps in the process. After actually grabbing the light, we get snarled in other thickets, such as how to refine it, how to use it as a compositional tool, even how to control its range in color and tone. All this takes time and patience and learning, and so I bow to no one in my adoration for the wizards who’ve helped me get there easier. The tools are changing incredibly fast and the benefits are bigger and deeper than ever before.

Take the idea of time exposure. The shot you see here was grabbed thirteen years ago, in the inky black of night, several hours after sunset, my camera, a crop-sensor DSLR, was mounted on a tripod and held open for ten seconds, allowing me to keep my ISO to 100, so zero noise. Jump ahead to 2025 and the larger, more sophisticated sensors of a full-frame camera, and it is nearly possible to take this photo handheld, albeit with a very high ISO that, amazingly, still comes out very, very clean. Is the tripod dead?

Certainly not, and you can draw up your own checklist of occasions that still call for it. Obsolescence happens slower than technical advancement (as witness the too-stubborn-to-die case of analog film). And yet. And yet we are that much closer to the tripod eventually going the way of the dodo, and in a remarkably brief stretch of time. That’s what I was pointing out at the top of this article; the fact that photography is swiftly getting to the point were excellence and flexibility are almost a given with present-day gear….with the steps needed to get the picture, to, in essence help us get out of our own way, being rapidly streamlined and simplified. Less calculating, more envisioning. Less adjustment, more captures. Every domino trips another domino trips another domino. Progress.

A CAMERA SETTING OF 120 OVER 80

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS MANY PHOTOGRAPHERS NO DOUBT CAN, I find it easy to look at images I’ve shot in different times of my life and fully recall the state of my mind at the time. I know which pictures correlate to difficult periods, and which photos are, in effect, a barometer on various occasions of contentment. In the case of both happy and challenging events, however, I regard the making of photographs to be restorative in itself, something that the scientific world has recognized for some time.

Let me be more clear: photography is an essential good for both the heart and the mind. Its procedures and techniques actually promote mental health, pulling you away from the gravitational suck of care and worry. I have long suspected that it produced a greater feeling of calm and focus in the case of me, myself, but a body of study is backing up a benefit that I used to assume was “only me”. In a 2025 issue of the online magazine fStoppers, entitled Why Photography Could Be the Mental Health Boost You Never Knew You Needed, writer/shooter Alex Cooke shares the good news:

The psychological benefits of photography aren’t just anecdotal; they’re rooted in well-established principles of cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness practice, and positive psychology. When someone engages in photography, they’re essentially practicing a form of present-moment awareness that mirrors many therapeutic techniques used by mental health professionals. The act of composing a shot requires the photographer to observe their environment carefully, notice details they might otherwise overlook, and make conscious decisions about what to include or exclude from the frame.

True feel-good stuff, I know. However, Cooke insists that the benefits of snapping are rooted in real science:

Research in neuroscience has shown that creative activities like photography can actually change brain structure and function in positive ways. When people engage in artistic pursuits, areas of the brain associated with reward processing, emotional regulation, and cognitive flexibility show increased activity. Over time, regular creative practice can strengthen neural pathways related to resilience and emotional stability. Photography, with its combination of technical skill, artistic expression, and problem-solving, activates multiple brain regions simultaneously, creating a rich neurological experience that supports mental health.

If an ideal blood pressure is around 120 over 80, then I can attest to having come closer to that mark the minute I pick up a camera. Alex Cooke’s article is extensive, but an easy read, and I recommend that you at least leaf through its findings. Creative people are doing more than merely commenting on the world; they are, in small but real measure, helping put it, and themselves, in order. And that is one pretty picture.