FROM TOY TO TOOL

Selective focus can help direct your viewer’s eye. Taken with a Lensbaby Spark lens at 1/80 sec., f/5.6, ISO 320, 50mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A LONG STANDING BIT ON THE DAVID LETTERMAN SHOW, rather than claiming to be entertaining, actually poses the question of what entertainment actually is. Entitled “Is This Anything?”, the feature consists of about thirty seconds of acts or feats that might be amazing (like juggling), might be banal (like, um, juggling) or might qualify as merely strange. After the curtain is drawn, Dave and Paul briefly discuss the merits of what ever strangeness just transpired, and ask each other if “that was anything”. Sometimes there is no clear-cut decision. The show has disclaimed responsibility, and entertainment remains in the eye of the beholder.

That’s how you can feel the first time you use a Lensbaby.

Released several years ago to inventor Craig Strong’s great monetary benefit, the Lensbaby comes in a variety of

levels but is essentially an affordable tilt-shift attachment, a way to soften focus over selective areas of the frame while rotating the “sweet spot” of sharper focus wherever the shooter feels it should go. Now, essentially, selective focus is really part of every photo ever taken, since a choice of depth-of-field is made every time the shutter snaps. Lensbaby, however, offers the chance to pre-design the precise level of left-right, high-low focus, in the camera, and before the shot is taken. No post-processing is needed, and each use of the effect is completely under the shooter’s control, and at a fraction of what dedicated DSLR lenses cost.The Lensbaby effect is understandably an attractive gimcrack for the instinctive subculture of lo-fi photography, they of the hipster nonchalance and light-leaking, fixed-focus plastic cameras. Hey, it looks freaky, random, edgy. But, like everything else in your kit bag, it’s either toy or tool. The verdict as to which it is comes out one picture at a time.

So far I am whelmed….not overwhelmed, not underwhelmed. For one thing, Lensbabies are a lot of extra work. The entry-level model, the Spark, is actually a lens within a springy plastic bellows. You have to hold your camera body, delegate fingers from both hands to rotate the axis of the front of the lens, squeeze the bellows to bring part of the frame into focus (the Spark’s “sweet spot” is fixed at f/5.6), allocate another finger for the shutter, and click. At least you can’t carp about not having enough creative control. There’s more than enough of that, especially at first, to O.D. on. Your chosen area of focus can be held in place more easily with upgrade models (which also include additional optics and add-ons), but the Lensbaby is truly best for shoots where you have a lot of time to think, plan, and create….the very opposite of the “shoot from the hip” attitude embraced by the lomography crowd. You will take a lot of pictures that miss by inches, or fractions of inches.

What will move me from whelmed to overwhelmed will be finding those images where the Lensbaby effect actually aids my storytelling, yet does not define it, as in the lucky shot at the top of this post. The camera gadgets I eventually consign to the “toy” pile go there because they call too much attention to what they can do, not to what I can do using them. The”tools” pile contains the gear that is essential to my saying something in a distinctly different voice. Finally, the two piles are divvied up only after taking lots of pictures and asking a ton of questions (a few gimmicks, like fisheye, have spent time in both piles; hey, I’m not above just playing around).

I sympathize with Letterman’s dilemma when he ironically asks, “Is this anything?” Selective focus is a way to install big neon pointers into your pictures, a more emphatic command to look over here. It’s also a way to amplify the drama of certain data or simplify cluttered compositions. I get it.

But it needs to be about much more than that. Or, more correctly, I have to help it.

Related articles

- My Lensbaby SCOUT, baby! (greyiscolour.wordpress.com)

ESCAPE FROM PLANET PORTRAIT

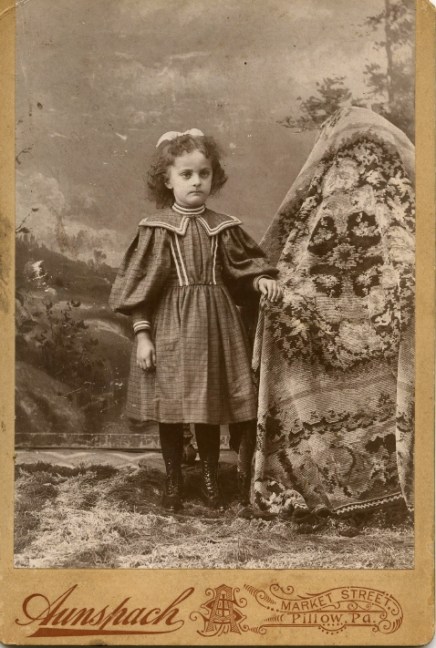

Does this child look happy to you? Does she look like she even has a pulse? Surely we do better kid portraits today, er, don’t we?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TO HEAR US TELL IT, WE ALL REALLY LOVE OUR KIDS. Assuming that to be true, why do we still subject them to the greatest act of photographic cruelty since Tod Browning’s Freaks? I speak of course, of the creatively bankrupt ritual of studio portraits, many of them cranked out at department stores or discount mills, too many of them making our beloved progeny look like waxworks escaped from a casting call for Beetlejuice.

We can surely do better.

I’m on record as believing that children are the noblest work of nature, coming into the world bearing only joy and untainted by the cynical clown olympics that comprise our “adult” way of thinking. And since we all probably feel the same way, why do so many of us park the little dears in front of hideous backdrops, surround them with absurd props, and gussy them up as everything from fairy princesses to ersatz puppies to fake cherubs?

Part of this ridiculous tradition owes its origins to the early days of photography, when a portrait sitting was the one means by which people who might never leave behind any other visual record of their lives were placed in formalized settings for an “official” rendering of their features. Slow film speeds and primitive lighting dictated that parents “leave it to the pros”, giving these modestly gifted artists decades of practice in weaving imaginary dream framings for our precious kids. (Full disclosure: Yes, I know that the image at left is a leftover from the Victorian age. I didn’t post any contemporary images because (a) many of them are almost this bad and you already get the idea, and (b) I wasn’t eager to be beaten to a pulp by any proud parents.)

Could it be more obvious, billions of Instamatics and Instagrams later, that this sad ritual hasn’t had any fresh air pumped into it since the golden age of Olan Mills class pictures? Even the most elementary “how-to” books on candid photography have been telling us the same thing for nearly a century: don’t formalize the setting, formalize your thinking. Let your child show you what he is, in his own environment. That means that you need to shoot constantly and invisibly, getting out of the kid’s way. No 3-2-1 “Cheese!” commands, no “sit up straight and don’t slouch” advice, no arbitrary situation.

Sure, you can basically plan how you will shoot your child, but allow him to unfold before your ready camera and gain the confidence to react in the moment. Stop trying to herd him into a structure or a setting. If at all possible, allow him to forget that you’re even in the room. Witness something wonderful instead of trying to construct it. Be a fly on the wall. The child is pitching great stuff every time he’s on the mound. Just make sure you’re behind the plate to to catch it.

Dirty little secret: there is nothing “magical” about most studio portraits. In fact, many of the results from the photo mills are just about the most un-magical pictures ever taken, although there are signs that things are changing. It simply isn’t enough to ensure a perfectly diffused background and an electronically exact flash. Even today’s most humble personal cameras have amazing flexibility to capture flattering light and isolate your subject from distracting backgrounds. And going from standard “kit” lenses (say, an 18-55mm) to an affordable prime lens (35mm, 50mm) gives us insane additional gobs of light to work with, all without using the dreaded pop-up flash, the photographic equivalent of child abuse.

Doing it yourself with kid portraits is work, make no mistake. You have to be flexible. You have to be fearless. And you have to know when something magical’s about to happen. But it’s your child, and there is no outside contractor who has a better sense of what delight he has inside him.

Besides, isn’t it likelier that he will show you the magic in his own back yard than in a back room at K-Mart? Give him something that he loves to do, the better to forget you’re there, and crank away. I mean shoot a lot. And don’t stop.

You’re the expert here.

Don’t outsource your joy.

THE ROOMS DOWN THE HALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR THESE PAGES, IT WAS NEVER MY VISION TO MERELY POST PICTURES. Not, at least, without some kind of context. Just meeting a regular deadline with the “picture of the day” held as little interest for me as maintaining a diary, an oppressive regularity that I have resisted my entire life. For the most part, the images on THE NORMAL EYE are here to anchor my thoughts about what it feels like to be enticed, seduced, enthralled, and, yes, disappointed by photography, to caption the frames with some semblance of the creative process, at least as I had the poor power to see it at the time.Like all blogs, it is written on my own very personal terms. I am always thrilled to harvest reaction and comment, since, as Ike Turner once sang, “was my plan from the very began”. But the important thing is to get the thoughts right, or at least to use them as a guide to the shots. Thus, the mission is neither words nor pictures, but some kind of handshake symbiosis between the two.

FOR THESE PAGES, IT WAS NEVER MY VISION TO MERELY POST PICTURES. Not, at least, without some kind of context. Just meeting a regular deadline with the “picture of the day” held as little interest for me as maintaining a diary, an oppressive regularity that I have resisted my entire life. For the most part, the images on THE NORMAL EYE are here to anchor my thoughts about what it feels like to be enticed, seduced, enthralled, and, yes, disappointed by photography, to caption the frames with some semblance of the creative process, at least as I had the poor power to see it at the time.Like all blogs, it is written on my own very personal terms. I am always thrilled to harvest reaction and comment, since, as Ike Turner once sang, “was my plan from the very began”. But the important thing is to get the thoughts right, or at least to use them as a guide to the shots. Thus, the mission is neither words nor pictures, but some kind of handshake symbiosis between the two.

However, since day one, I have reserved several gallery pages on which visual info is pretty much all there is, since I also believe that it is important to react to photographs on a purely visceral basis. If the blog is the main hall in the house, think of these as the rooms down the hall that you never thought to explore.

I have tried to give each gallery its own general feel, since there are different “themes” which motivate our taking of pictures, and I thought, for this post, it might be helpful to underscore those themes just enough to justify how they were organized. I have now also given them specific names instead of the A-B-C tags they had previously.

Here’s the new rundown:

Gallery A is now “HDR”, since I think that this process affords very specific benefits for reproducing the entire range of visible light in a way that, until recently, has been impracticable for many shooters. No tool is suitable for every kind of shooting situation, but HDR comes close to reproducing what the eye sees, and can enhance detail in fascinating ways. There is a lot controversy over its best use, so, like everywhere else on this blog, your opinions are invited.

The former B gallery is a collection of impulse shots. All of these images were taken in the moment, on a whim, with only instinct to guide me. No real formal prep went into the making of any of them, as they were the product of those instants when something just feels right, and you try to snag it before it vanishes. We’ll call these “SNAP JUDGEMENTS”.

And finally, the photos formerly known as Gallery “C” are now renamed “NATURAL STATE”, as these portraits are all shot using available light, captured without flash or the manipulation of light through reflectors, umbrellas, or other tools.

Let me state here that your participation in this forum was always the centerpiece of my doing it in the first place, and your ideas and suggestions have always inspired me to try to be worthy of the space I’m taking up. I also have enjoyed linking back to your individual sites and visions. It’s a great way to learn.

ideas and suggestions have always inspired me to try to be worthy of the space I’m taking up. I also have enjoyed linking back to your individual sites and visions. It’s a great way to learn.

So please know that, when you click the “like” button at the bottom of these posts, or take the time to type a comment, it does help me see what works, as well as what needs to be done better. I don’t believe that art can grow in a vacuum, and I thank everyone for giving these pages shape and form.

And thanks for exploring all the rooms in my house.

FLATTERY WILL GET YOU NOWHERE

My beautiful mother, well past 21 but curator of a remarkable face. Window light softens, but does not erase, the textures of her features. 1/60 sec., f/4.5, ISO 200. 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE DEPICTION OF THE FACES OF THOSE WE LOVE IS AMONG THE MOST DIVISIVE QUESTIONS IN PHOTOGRAPHY. Since the beginning of the medium, thoughts on how to capture them “best” clearly fall into two opposing camps. In one corner, the feeling that we must idealize, glamorize, venerate the features of those most special in our lives. In the other corner, the belief that we should capture faces as effects of time and space, that is, record them, without seeking to impose standards of grace or beauty on what is in front of the lens. This leads us to see faces as objects among other objects.

The first, more cosmetic view of faces, which calls for ideal lighting, a flattering composition, a little “sweetening” in the taking, will always be the more popular view, and its resultant images will always be cherished for emotionally legitimate reasons. The second view is, let’s “face” it, a hard sell. You have to be ready for a set series of responses from your subjects, usually including:

Don’t take me. I just got up.

God, I look so old. Delete that.

I hate having my picture taken.

That doesn’t even look like me.

Of course, since no one is truly aware of what they “look like”, there is always an element of terror in having a “no frills” portrait taken. God help me, maybe I really do look like that. And most of us don’t want to push to get through people’s defenses. It’s uncomfortable. It’s awkward. And, in this photo-saturated world, it’s a major trick to get people to drop their instinctive masks, even if they want to.

Still.

As I visually measure the advance of age on my living parents (both 80+ ) and have enough etchings on my own features to mirror theirs, I am keener than ever to avoid limiting my images of us all to mere prettiness. I am particularly inspired by photographers who actually entered into a kind of understanding with their closest life partners to make a sort of document out of time’s effects. Two extreme examples: Richard Avedon’s father and Annie Leibovitz’ partner Susan Sontag were both documented in their losing battles with age and disease as willing participants in a very special relationship with very special photographers….arrangements which certainly are out of the question for many of us. And yet, there is so much to be gained by making a testament of sorts out of even simple snaps. This was an important face in my life, the image can say, and here is how it looked, having survived more than 3/4 of a century. Such portraits are not to be considered “right” or “wrong” against more conventional pictures, but they should be at least a part of the way we mark human lives.

Everyone has to decide their own comfort zone, and how far it can be extended. But I think we have to stretch a bit. Pictures of essentially beautiful people who, at the moment the shutter snaps, haven’t done up their hair, put on their makeup, or conveniently lost forty pounds. People in less than perfect light, but with features which have eloquent statements and truths writ large in their every line and crevice. We should also practice on ourselves, since our faces are important to other people, and ours, like theirs, are going to go away someday.

In trying to record these statements and truths, mere flattery will get us nowhere. The camera has an eye to see; let’s take off the rose-colored filter, at least for a few frames.

Related articles

- The Great Richard Avedon (sandroesposito.wordpress.com)

LET THERE BE (MORE) LIGHT

A new piece of glass makes everything look better….even another piece of glass. First day with my new 35mm prime lens, wide open at f/1.8, 1/160 sec., ISO 100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE RECENTLY BEEN EXPERIENCING ONE OF THOSE TIME MACHINE MOMENTS in which I am, again, right back at the beginning of my life as a photographer, aglow with enthusiasm, ripe with innocence, suffused by a feeling that anything can be done with my little black box. This is an intoxication that I call: new lens.

Without fail, every fresh hunk of glass I have ever purchased has produced the same giddy wonder, the same feeling of artistic invincibility. This time out, the toy in question is a Nikon f/1.8 35mm prime lens, and, boy howdy, does this baby perform. For cropped sensor cameras, it “sees” about like the 50mms of old, so its view is almost exactly as the human eye sees, without exaggerated perspective or angular distortion. Like the 50, it is simple, fast, and sharp. Unlike the 50, it doesn’t force me to do as much backing up to get a comfortable framing on people or near objects. The 35 feels a little “roomier”, as if there are a few extra inches of breathing space around my portrait subjects. Also, the focal field of view, even wide open, is fairly wide, so I can get most of your face tack sharp, instead of just an eye and a half. Matter of preference.

All this has made me marvel anew at how fast many of us are generally approaching the age of flashless photography. It’s been a long journey, but soon, outside the realm of formal studio work, where light needs to be deliberately boosted or manipulated, increasingly thirsty lenses and sensors will make available light our willing slave to a greater degree than ever before. For me, a person who believes that flash can create as many problems as it solves, and that it nearly always amounts to a compromise of what I see in my mind, that is good news indeed.

It also makes me think of the first technical efforts to illuminate the dark, such as the camera you see off to the left. The Ermanox, introduced by the German manufacturer Ernemann in 1924, was one of the first big steps in the quest to free humankind of the bulk, unreliability and outright danger of early flash. Its cigarette-pack-sized body was dwarfed by its enormous lens, which, with a focal length of f/2, was speedy enough (1/1000 max shutter) to allow sharp, fast photography in nearly any light. It lost a few points for still being based on the use of (small) glass plates instead of roll film, but it almost single-handedly turned the average man into a stealth shooter, in that you didn’t have to pop in hefting a lotta luggage, as if to scream “HEY, THE PHOTOGRAPHER IS HERE!!” In fact, in the ’20’s and ’30’s, the brilliant amateur shooter Erich Solomon made something of a specialty out of sneaking himself and his tiny Ermanox into high-level government summits and snapping the inner circle at its unguarded best (or worst). Long exposures and blinding flash powders were no longer part of the equation. Candid photography had crawled out of its high chair… and onto the street.

Today or yesterday, this is about more than just technical advancement. The unspoken classism of photography has always been: people with money get great cameras; people without money can make do. Sure, early breakthroughs like the Ermanox made it possible for anyone to take great low-light shots, but at $190.65 in 1920’s dollars, it wasn’t going to be used at most folks’ family picnics. Now, however, that is changing. The walls between “high end” and “entry level” are dissolving. More technical democracy is creeping into the marketplace everyday, and being able to harness available light affordably is a big part of leveling the playing field.

So, lots more of us can feel like a kid with a new toy, er, lens.

Related articles

- Prime Lenses (nikonusa.com)

- Understanding Focal Length (nikonusa.com)

THE PROSCENIUM

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT IS THE OLDEST FRAMING DEVICE IN HISTORY. If you’ve ever watched a play on any stage, anywhere in the world, you’ve accepted it as the classic method of visual presentation. The Romans coined the word proscenium, “in front of the scenery”. Between stage left and stage right exists a separate reality, defined and contained in the finite space of the theatre’s forward area. What is included in the frame is everything, the center of the universe of certain characters and events. What’s outside the frame is, indefinite, vague, less real.

Just like photography, right? Or to be accurate, photography is like the proscenium. We, too select a specific world to display. We leave out all the other worlds not pertinent to our message. And we follow information in linear fashion…left to right, right to left. The frame gives us the sensation of “looking in” to something that we are only visiting, just as we only “rent” our viewpoint from our theatre seats.

We learned our linear habit from the descendants of stage arrangement….murals, frescoes, paintings, all working, as our first literate selves would, from left to right. Painters were forced to arrange information inside the frame, to make choices of what that frame would include, and, as the quasi-legitimate children of painting, we inherited that deliberately chosen viewpoint, that decision to show a select world, by arranging visual elements within the frame.

Park Slope, Brooklyn, 2012. Trying to catch as much activity as a street glance, at any given moment, can. 1/320 sec., F/7.1, ISO 100, 24mm.

For some reason, in recent months, I have been abandoning the non-traditional in shooting street scenes and harking back to the proscenium, trying to convey a contained world of simple, direct left-right information. Candid neighborhood shots seem to work well without extra adornment. Just pick your borders and make your capture. It’s a way of admitting that some worlds come complete just as they are. Just wrap the frame around them like a packing crate and serve ’em up.

Like a theatre play, some images read best as self-contained, left-to-right “worlds”. A firehouse in Brooklyn, 2012. 1/60 sec., f/6.3, ISO 100, 38mm.

This is not to say that an angled or isometric view can’t portray drama or reality as well as a “stagy” one. Hey, sometimes you want a racing bike and sometimes you want a beach cruiser. Sometimes I don’t mind that the technique for getting a shot is, itself, a little more noticeable. And sometimes I like to pretend that there really isn’t a camera.

That’s theatre. You shouldn’t believe that the well-meaning director of the local production of Oklahoma really conjured a corn field inside a theatre. But you kind of do.

Hey what does Picasso say? “Art is the lie that tells the truth”?

Okay, now I’m making my own head hurt. I’m gonna go lie down.

DREAMS DOWN TO DUST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT WAS, ON ONE LEVEL, A COMPLETE WASTE OF GASOLINE: a half-hour’s drive to a dusty cluster of tables scattered across a vacant lot in Carefree, Arizona; a gathering of junk gypsies, hunkering for shade under their teepee nation of display tents, their sprawls of pre-owned debris bunched onto card tables filled with the remains of people’s lives. It was going to take exactly five minutes to make one sad pass around this serpentine mound of resale refuse. No treasures today. Maybe we have time to catch lunch before we drive back to town.

These strange mash-ups of godforsaken bric-a-brac are common in many of the small towns of the southwest. Sometimes they are found shoehorned into sagging old adobe buildings on their umpteenth re-use. Other times they are charitably called “swap meets” or “vintage sales” and litter the parking lots of down-and-out drive-in theatres like the aftermath of an air crash. The visual impact is always the same, that of an attic that has been dynamited to bits, then shoveled into milk cartons and slapped with improvised glo-orange price tags. Coffee cans filled with unrelated fragments of trinkets; cardboard cartons overflowing with random chunks of household backfill. Two mysteries pervade: where has all of this come from….and where can it possibly be heading?

I was about one minute away from the end of my doleful tour when I spotted this box, which someone had filled with mis-matched bits of small dolls. One of such souvenirs on a big table makes no visual impression whatever, but a mass of them together is some kind of little minor-key symphony of dreams gone down to dust. Loved objects that were once transformed into the stuff of fancy, now just shards of lives dumped into a cigar box. I risked one picture. For some reason it haunts me.

But see what you think.

It isn’t about what we look at but what we see.

We leave such a colossal wake of trash behind us as our lives thunder and crash through the world. How to sort out all the stories inside?

SMILE! OR NOT.

Since we’re usually unhappy with the way others capture us, we have nothing to lose by a making a deliberate effort to come closer to the mark ourselves. Self-portraits are more than mere vanity; they can become as legitimate a record of our identities as our most intimate journals. 1/15 sec., f/7.1, ISO 250, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A COMMONLY HELD VIEW OF SELF-PORTRAITURE is that it epitomizes some kind of runaway egotism, an artless symbol of a culture saturated in narcissistic navel-gazing. I mean, how can “us-taking-a-picture-of-us” qualify as anything aesthetically valid or “pure”? Indeed, if you look at the raw volume of quickie arm’s length shots that comprise the bulk of self-portrait work, i.e., here’s me at the mountains, here’s me at the beach, etc., it’s hard to argue that anything of our essence is revealed by the process of simply cramming our features onto a view screen and clicking away…..not to mention the banality of sharing each and every one of these captures ad nauseum on any public forum available. If this is egotism, it’s a damned poor brand of it. If you’re going to glorify yourself, why not choose the deluxe treatment over the economy class?

I would argue that self-portraits can be some of the most compelling images created in photography, but they must go beyond merely recording that we were here or there, or had lunch with this one or that one. Just as nearly everyone has one remarkable book inside them, all of us privately harbor a version of ourselves that all conventional methods of capture fail to detect, a visual story only we ourselves can tell. However, we typically carry ourselves through the world shielded by a carapace of our own construction, a social armor which is designed to keep invaders out, not invite viewers in. This causes cameras to actually aid in our camouflage, since they are so easy to lie to, and we have become so self-consciously expert at providing the lies.

The portraits of the famous by Annie Liebovitz, Richard Avedon, Herb Ritts and other all-seeing eyes (see links to articles below) have struck us because they have managed to penetrate the carapace, to change the context of their subjects in such dramatic ways that they convince us that we are seeing them, truly seeing them, for the first time. They may only be doing their own “take” on a notable face, but this only makes us hunger after more interpretations on the theme, not fewer. Key to many of the best portraits is the location of their subjects within specific spaces to see how they and the spaces feed off each other. Sometimes the addition of a specific object or prop creates a jumping off point to a new view. Often a simple reassignment of expression (the clown as tragedian, the adult as child, etc) forces a fresh perspective.

As for the self-portrait, an artistic assignment that I feel everyone should perform at least once (as an intentional design, not a candid snap), there is a wealth of new information gleaned from even an indifferent result. Shooters can act as lab rats for all the ways of seeing people that we can think of to play at, serving as free training modules for light, exposure, composition, form. I am always reluctant to enter into these projects, because like everyone else, I balk at the idea of centering my expression on myself. Who, says my Catholic upbringing, do I think I am, that I might be a fit subject for a photograph? And what do I do with all the social conditioning that compels me to sit up straight, suck in my gut, and smile in a friendly manner?

One can only wonder what the great figures of earlier centuries might have chosen to pass along about themselves if the self-portrait has existed for them as it does for us. What could the souls of a Lincoln, a Jefferson, a Spinoza, an Aquinas, have said to us across the gulf of time? Would this kind of introspection been seen by them as a legacy or an exercise in vanity? And would it matter?

In the above shot, taken in a flurry of attempts a few days ago, I am seemingly not “present” at the proceedings, apparently lost in thought instead of engaging the camera. Actually, given the recent events in my life, this was the one take where I felt I was free of the constraints of smiling, posing, going for the shot, etc. I look like I can’t focus, but in catching me in the attempt to focus, this image might be the only real one in the batch. Or not. I may be acting the part of the tortured soul because I like the look of it. The point is, at this moment, I have chosen what to depict about myself. Accept or reject it, it’s my statement, and my attempt to use this platform to say something, on purpose. You and I can argue about whether I succeeded, but maybe that’s all art is, anyway.

Thoughts?

Related articles

- Avedon For Breakfast (fabsugar.com)

- Getty Center Exhibits Herb Ritts and Celebrity Portraits (ginagenis.wordpress.com)

- Annie Leibovitz: ‘Creativity is like a big baby that needs to be nourished’ (guardian.co.uk)

GLO-SCHTICK

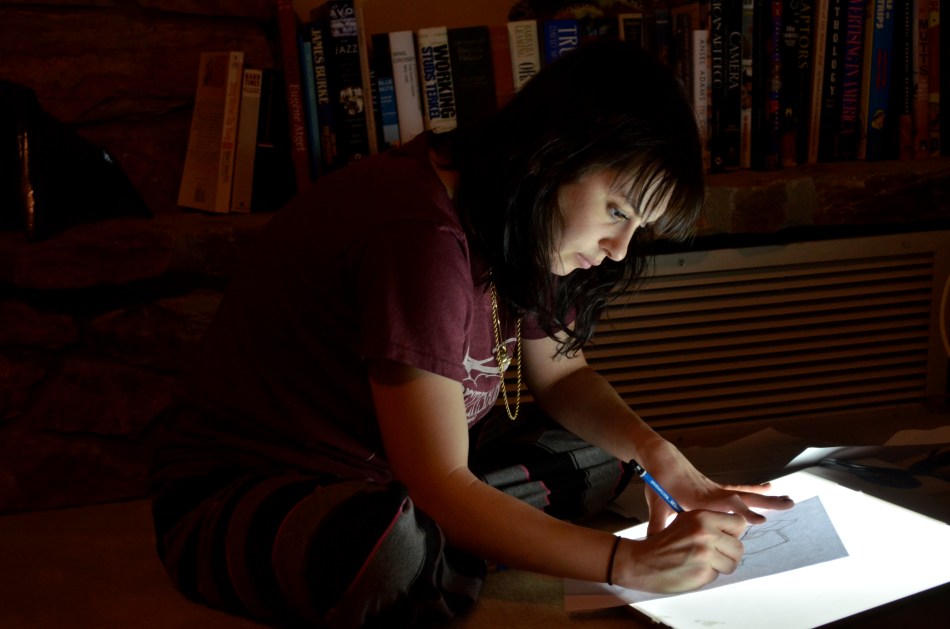

Sometimes just a bit is just enough. A bump up to ISO 640 kept me fairly free of noise and allowed me to use the screen’s glow as my only light source. 1/30 sec., f/5.6 at 52mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE BEST TECHNIQUE is one that does not scream for attention like a neon t-shirt emblazoned with the phrase LOOK WHAT I DID.

Now, of course, we are all messing around backstage, working hard to make the elephant disappear. We all manipulate light. We all nudge nature in the direction we’d prefer that she go. But what self-respecting magician wants to get caught pulling the rabbit out of a hole in the table?

I recently had the perfect low-light solution handed to me as I watched a young designer working in a dim room, and, thankfully, only marginally aware of my presence. “Lighting 101” dictated that, to get a sense of her intense concentration, I send the most important light right to her face.

Turns out, a light tracer screen, in a pinch, makes a perfect softbox.

Better yet, the light from the screen thinned out and dampened after it traveled left past her shoulders, leaving just enough illumination to keep the rest of the frame from falling off completely into black, making the face the lone story-teller. An ISO bump to 640 and a white balance tweak were enough to grab the best of what the screen had to give. At this point in the “gift from the gods” process, you click, and promise, in return, to live a moral life.

Sometimes you don’t have to do anything extra to make a thing look like it actually was. That’s better than finding a hundred-dollar bill on the street.

Well, almost.

What was your best light luck-out?