STREAMING KILLED THE THEATRE STAR?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS YOU READ THIS, ANYONE WITH A KEYBOARD AND THE MINUTEST CONNECTION TO THE ENTERTAINMENT BIZ is crapping bricks over the sale of Warner Brothers to yet another new owner, (of which there have been more than a dozen), regarding said merger/sale as the death knell for theatrical movies in the Golden Age Of Streaming. This mass panic ignores the fact that “going to the movies”, as a regular practice, has been heading for Dodo-land for decades, and that, sorry folks, but things change and evolve. We will always love storytelling, but we will constantly be revising the delivery system we choose to use. Ask the 1920’s studio heads that predicted that “talkies” were a passing fad.

For me, the major sensory delight of going out to a film has been gone for some time, being intertwined as it was with the atmosphere engineered into the theaters built in the first third of the 1900’s. The over-the-top grandiloquence, the overkill raised to a the status of a science, immersed the moviegoer in rich fantasy worlds that provided vivid escape even before the curtain went up (yes, Virginia, there were curtains) and the overture began (and, yes, Virginia, there were overtures, as well). We had a deep, profound crush on the places where movies were shown, a crush that was trampled underfoot in the back half of the twentieth century, as those miraculous movie palaces were replaced with bland boxes, mere assembly halls equipped with projectors. They were certainly places we went to see movies, but they ceased to be…. theaters.

I live near Los Angeles now, and being a frequent day-trip visitor, I have inherited a plethora of dozens of grand old movie houses that, in the town that perfected make-believe, have been allowed to age into the 2000’s, repurposed either as subdivided multi-screen complexes, playhouses, or live performance venues. It’s the kind of legacy that has long since vanished from much of the heartland, and, as a photographer, I get a little drunk with power at the chance to walk their halls and document their dreamscapes. The images here are from a medium-sized 1930 cinema called the Saban, which hosts any and every kind of entertainment event at its original location on Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills. I love movies, and I always will. I also used to love where I went to love movies. Now, late in the game, I have more chances than ever to leaf through the scrapbook of that romance. Mergers be damned, it really wasn’t streaming that killed the theatre star; that particular murder has a hundred different authors.

SUPER STAND-INS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

Los Angeles’ E.Clem Wilson building, the first structure to portray the Daily Planet on film.

SINCE ITS VERY BEGINNINGS, THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY has made bank by creating and marketing alternative realities, visions of what they hope we’ll believe, at least until the last frame of film clears the projector gate. So lasting are some of these illusions that they become more authentic than the actual in-life objects or locations that were used to generate them.

In my own case, one of the first and most influential times a thing from the “real” world was re-purposed to stand for something else was in my daily viewing of reruns of The Adventures Of Superman, in which exteriors of various Los Angeles landmarks were substituted for key locations in the Man Of Steel’s fictional world. Of course, at the age of seven, I tended to take everything Hollywood presented to me at absolute face value; if the storytellers told me a thing was so, that was it, as far as I was concerned. So of course, when I saw a shot of the E. Clem Wilson building (in the earliest episodes of the show) or the Los Angeles City Hall (for the later stories), I knew that actually, they were the headquarters of the Daily Planet, the hallowed shrine of journalism in which Clark and Lois and Jimmy clacked away at Royal typewriters in pursuit of The Next Big Scoop.

Los Angeles City Hall, which followed the Wilson building as the second version of the Planet on the Adventures Of Superman TV series.

Of course, as a lad, I I knew nothing of the film industry’s century-long habit of saving a buck by using stock shots to stand in for something that they didn’t want to build from scratch. I saw exactly what they wanted me to see, and thought about it exactly how they wanted me to think. At that age, I certainly didn’t have any sense that film-makers, just like propagandists or documentarians, could make me look at an image and draw associations from it that had no root in fact. A few years later, as I stumbled into photography, I developed my own ideas on how to idealize the things I shot. Being a total noob, I thought everything I pointed my camera at was important, or beautiful, because that’s what the process of making a picture felt like to me. Years later, when I looked at my earliest “good” pictures, I was amazed at how truly horrible many of them were, and how, in my my mind’s eye, I had wildly over-inflated their value. Eye of the beholder and all that.

At this writing, in early 2025, yet another cinematic reboot of the Superman myth is being readied for the screen, and yet another visual symbol of the Planet building will be needed for the present generation. However, unlike the producers of Adventures Of Superman, who were bringing in every episode of the show at a rock-bottom budget of about $15,000, the new crew won’t have to settle for just shooting some random place and merely renaming it. CGI and other tools will make literally anything possible. And yet I still find myself going back to the L.A. City Hall, where, somewhere in one of the Planet’s vast corridors, there is that miraculous storage room into which Clark Kent disappears to become The World’s Mightiest Mortal. For my inner seven-year-old, you can’t get any more “real” than that. And that’s the superpower of photography. Superman may be able to bend steel in his bare hands, but a picture can twist reality to any purpose.

THE ILLUSION OF AN ILLUSION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LOS ANGELES’ ACADEMY MUSEUM OF MOTION PICTURES is, in a town veritably built upon buzz, one thing that more than lives up to the hype, a dazzling treasure house that celebrates the entire history of Hollywood magic-making. Packed with exactly what you’d expect from a century of trophy hoarding by the same folks who brought you the Oscars, the Academy Museum is the place where you go to catch an up-close encounter with Dorothy’s ruby slippers or Charles Foster Kane’s sled. But as amazing as the permanent collection at the AMMP is, the special exhibitions are even more astonishing.

An offer you can’t refuse, at least with a digital camera: f/4, 28mm, ISO 3200, 1/30sec, handheld.

One of the museum’s key attractions from 2024, ending early in 2025, is an entire wing honoring the 50th anniversary of the release of “The Godfather”. Some of the exhibits are of the standard museum variety, with costumes and fashion sketches of the main characters or an original script draft from Mario Puzo, complete with red-pen notations and revisions from director Francis Ford Coppola. The feature which, alone, is worth the price of admission, though, is a stunning re-creation of the set for Don Corleone’s office, the room where the first definitive sequences of the film are staged. Perfect down to the Nth detail, the area is the kind of stunt only Hollywood could pull off; the illusion of something that was an illusion in the first place.

What gives the entire set its greatest ring of authenticity, however, is the duplication of the minimal lighting that was used by cinematographer Gordon Willis, a deep universe of shadow that threatened to swallow everyone in a menacing murk. The veteran film maker had to drastically re-invent whole processes to get acceptable exposure on the severely under-lit set, and the Academy Museum’s replication of that atmosphere is what most excites visiting photographers. To get clear, noise-free results, handheld, with today’s digital sensors, most of which can crank their light sensitivity up to levels undreamed of in the film world of the early 1970’s…well, it’s like some nerd shooter’s fever dream. And Hollywood, in the worldly wise words of Sam Spade is, indeed, the stuff that dreams are made of.

INSIDE EYE OF AN OUTSIDER

Picture of an actor playing a picture-maker taken by a picture-making actor: Dennis Hopper’s candid portrait of “Blow-Up” star Devid Hemmings, 1968.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

DENNIS HOPPER’S FILM CAREER STANDS TODAY as one of the iconic cautionary tales about what happens when one’s talent enters into a death struggle with one’s demons. He was the contemporary of another troubled actor, James Dean, but instead of smashing himself to pieces in a car crash all at once, like his friend, he was destined to unravel slowly, over decades, like a hideless baseball wobbling over the rear fence, caroming from suspension to firing, from screw-up to royal screw-up. Every time the candle of Hopper’s undeniable gifts began to truly glow brightly, he’d get too close to it and burn his eyebrows off.

Today, Hopper’s long stretch as an actor, writer and director has largely been boiled down, in the public memory, to his creative energies on the era-defining Easy Rider, with many of his other near misses blurring into the haze of the unique amnesia that is showbiz’ permanent dream state. However, since his passing in 2010, it is his other output, the 18,000 images he made as an amateur photographer between 1961 and 1968, that have burnished his legend, making his informal snaps of life among the famous and anonymous of Los Angeles in the ’60’s the stuff of coffee table books and gallery shows. Gifted with a Nikon on his birthday in 1961, Hopper trained it constantly on the people he worked with, as well as those he would, sadly, never work with. The result is a portfolio that is as essential as Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time In Hollywood in its depiction of the dreams, excesses and delusions among the showmakers and the stars they spawned in that vanished decade.

Hopper’s 1962 portrait of fellow cineaste Andy Warhol.

During his life, various collections of Hopper’s work, including In Dreams and Photographs 1961-1967 were published in book form, and a comprehensive showing at Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art accelerated interest among people who were only passingly familiar with his acting work. In the years since his death, his images have increasingly served as a time capsule for a Hollywood that was sandwiched between the end of the old studio system and the invasion of a younger generation of actors/directors that would include the Scorceses and Spielbergs of a new era. Hopper found a different kind of voice outside the world of movies, but one of his quotes about his first career seemed to portend the power of his second: “I was very shy, and it was a lot easier for me to communicate if I had a camera between me and people.”

OF DREAMS AND DUST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN A WORLD THAT SO SURGICALLY SORTS ALL MORTAL PLAYERS into winners and losers, it seems inevitable that we would devise systems by which the ”L”s might aspire to join the “W”s….some kind of schooling or preparation that transforms some of us, the one who are coal, into The Anointed, the ones designated to be Diamonds. Often, that sorting process comes in the form of commercial consumption, and one of its Meccas is Hollywood.

A photographer on the loose in Tinseltown becomes aware early on that all its shops and attractions, all its tour stops and theme parks, are actually one big Academy Of Making It, a huge machine that models the behaviors of the Chosen, a tutorial on how to persuade the Choosers to ask you into the club. And the most obvious cues occur at retail level.

Across every souvenir stand and shirt shoppe, the message is clear: winners buy this: winners wear these. If you don’t see anything here that looks like your look, your look is wrong. Hollywood purports to be about dreams, but it is also about nightmares, like the fever dream of not belonging to The Crowd, of not being plucked out of the chorus.

Whether the scenes we encounter on our streets are of victory or despair, the camera bears witness to the ongoing emotional high wire act. Hollywood is a uniquely American construct, which, like this all-night souvenir stand, encompasses both our desires and our defeats in the single act of selling us stuff…symbols, myths, ways of keeping score. It’s a special kind of envy-driven loneliness that’s also an industry that feeds on itself.

OSCAR’S CRADLE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

HOLLYWOOD IS ONE OF THE SELECT LOCALITIES in the world’s largest democracy where royalty is not only tolerated but slavishly sought after. The crown (or crowns, plural) transfer from the recently fallen to the newly anointed with predictable regularity, but the ritual is always the same: we love the common people (they’re just like us!) until they are lucky enough to escape our ranks, after which we, in turn, adore them, despise them (who do they think they are?), forgive them, and adore them anew.

In terms of photography, the camera seeks out ever new lovers, nearly all of them human, and therefore fleeting. A careful study of Tinseltown, however reveals that the true royalty, the royalty that endures, is the real estate. And even in a town where “reality” is defined by whether you shoot on location or on the back lot, Hollywood harbors plenty of actual places where actual events actually occurred. Some are on the bus tours (Marilyn Monroe slept here), while others require a bit more digging. One of the industry’s most prestigious addresses is smack dab in a section so spectacularly tacky that, by virtue of merely being merely ostentatious, it seems positively muted.

The Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel (named in memory of Teddy, not Franklin) survives in legend not because it served as a studio or corporate cradle for the film industry, but because it was the first time the town turned out to honor….itself. Then make an annual habit of it. Hey, if you want modesty, live in Des Moine, okay?

The Roosevelt earned its filmic pedigree from the get-go, financed in 1926 by a group that included MGM chief Louis B.Mayer and screen idols Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks (two-fourths of the founding quartet behind United Artists Pictures, along with Charlie Chaplin and director D.W. Griffith). Two years later, the hotel hosted a modest little dinner for 270 guests to fete honorees of the newly organized Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, some three months after the actual awards had been handed out, and minus the nickname “Oscars”, which would come about four years later.

Over the decades the Roosevelt and its across-the-street neighbor the Chinese Theatre (which opened within months of the “R”‘s premiere) saw a fairly staid business district transformed into “Hollywood & Highland” (trade mark)…. Sucker Bait Central, a day-glo drag whose countless souvenir stops, IMAX pleasure palaces, low-rent novelties and neon knock-offs raised tackiness to the status of a religious movement. Meanwhile, the hotel’s crazy-quilt architectural style (‘Spanish Colonial Revival’…and, yes, there will be a test later), with its coffered ceilings, mid-century pool cabanas and wrought-iron chandeliers, was just fake-elegant enough to pass for average in a town renowned for its, er, flexible relationship with “class”. Rolling through the years with an occasional ownership transfer and the odd walk-on in movies like Beverly Hills Cop II and Catch Me If You Can, the Roosevelt has recently offered lodging as a contest prize on ABC’s Jimmy Kimmel Live!, and landed landmark status as Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #545.

The Roosevelt’s photographic riches lie chiefly in its extremely dark main and elevator lobbies, its still-regal pool area and the legendary Cinegrill Lounge. The lobbies, at least for handheld shots, require high ISOs, slow shutter speeds and wide apertures. Flash may not be verboten but you won’t like the result, trust me. Indeed, the soft gold afforded by natural light washing into the murk from outside brings out the warmth of the Spanish textures, and adds a little tonal nostalgia to the scene. All things together, the Roosevelt stands as a monument to real occurrences, some of them fairly historically significant, in The Town That Invented Phony. And that’s the main challenge in Hollywood: if you can fake sincerity, the rest is easy.

INSIDE THE OUTSIDE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S HARD TO ATTRACT ATTENTION IN HOLLYWOOD, a town that shouts in five dimensions, a million colors, and four thousand decibels about almost everything. Here, in the town that hype calls home, design always swings for the fences, and Subtle Is For Sissies. Small wonder, then, that photographers, who typically love to play top this with their peers, find that Tinseltown and greater L.A. are already at gold medal status in playing the very same game. I’ll see your weird, and raise you two weirders.

As a street shooter in Hollywood/L.A., you routinely witness the bizarre being passed off as the normal. As a consequence, the very act of visually commenting on this mad sensual overdose can make even your most prosaic shots seem like a trip through the looking glass. Words like stately, venerable, or traditional seem oddly out of place in the town that invented fourteen-story billboards and the Walk of Fame. Using a camera to say something new about it all can be a fool’s errand, or at least, a mental obstacle course.

Whenever I visit Los Angeles, I am constantly looking for some kind of reversal pattern, a way to treat the most outrageous visual artifacts on their heads. I don’t always succeed. I did, however, have fun trying, recently, to come up with a new way of seeing a very strange building, the Peterson Automotive Museum, located at the intersection of Wilshire Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue, the outside of which has undergone a very radical facelift in recent years. From afar, the building seems to be a wild, untethered series of curves and swoops, a mobius strip of red and steel spaghetti floating in space in an abstract suggestion of motion. It’s a stunning bit of sculpture that actually is a wrap-around of the original, far more conventionally-shaped museum building beneath it.

And, as it turns out, that’s the way to reverse-engineer a photo of the museum, since it’s possible to walk behind the swirly facade and into a shadow-and-color-saturated buffer space that exists between it and the underlying structure. From inside said space you can view the outer bands as a peekaboo grid through which you can view neighboring buildings and local traffic, rather like looking between the slats of some big psychedelic set of venetian blinds. And that’s where I stood when taking the above shot with a Lensbaby Composer Pro lens with a fisheye optic, the aperture set at about f/5.6 to render the whole thing somewhat soft and dreamy. I’ll see your two weirders and raise you one bizarre.

25, 50, T, B

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A PART OF WILSHIRE BOULEVARD IN LOS ANGELES that I have been using for a photographic hunting ground for over ten years, mostly on foot, and always in search of the numerous Art Deco remnants that remain in the details of doors, window framings, neighborhood theatres and public art. Over the years, I have made what I consider to be a pretty thorough search of the stretch between Fairfax and LaBrea for the pieces of that streamlined era between the world wars, and so it was pretty stunning to realize that I had been repeatedly walking within mere feet of one of the grand icons of that time, busily looking to photograph….well, almost anything else.

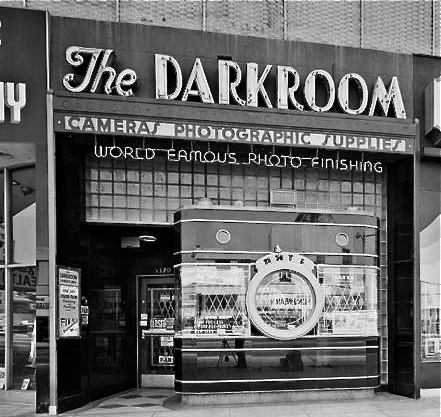

A few days ago, I was sizing up a couple framed in the open window of a street cafe when my composition caught just a glimpse of black glass, ribbed by horizontal chrome bands. It took me several ??!?!-type minutes to realize that what I had accidentally included in the frame was the left edge of the most celebrated camera in all of Los Angeles.

Opened in the 1930’s, the Darkroom camera shop stood for decades at 5370 Wilshire as one of the greatest examples of “programmatic architecture”, that cartoony movement that created businesses that incorporated their main product into the very structure of their shops, from the Brown Derby restaurant to the Donut Hole to, well, a camera store with a nine-foot tall recreation of an Argus camera as its front facade.

The surface of the camera is made of the bygone process known as Vitrolite, a shiny, black, opaque mix of vitreous marble and glass, which reflects the myriad colors of Los Angeles street life just as vividly today as it did during the New Deal. The shop’s central window is still the lens of the camera, marked for the shutter speeds of 1/25th and 1/50th of a second, as well as T (time exposure) and B (bulb). A “picture frame” viewfinder and two film transit knobs adorn the top of the camera, which is lodged in a wall of glass block. Over the years, the store’s original sign was removed, and now resides at the Museum of Neon Art in Glendale, California, while the innards of the shop became a series of restaurants with exotic names like Sher-e-Punjab Cuisine and La Boca del Conga Room. Life goes on.

True to the ethos of L.A. fakes, fakes of fakes, and recreations of fake fakes, the faux camera of The Darkroom has been reproduced in Disney theme parks in Paris and Orlando, serving as…what else?….a camera shop for visiting tourists, while the remnants of the original storefront enjoy protection as a Los Angeles historic cultural monument. And, while my finding this little treasure was not quite the discovery of the Holy Grail, it certainly was like finding the production assistant to the stunt double for the stand-in for the Holy Grail.

Hooray for Hollywood.

REAL PHONIES

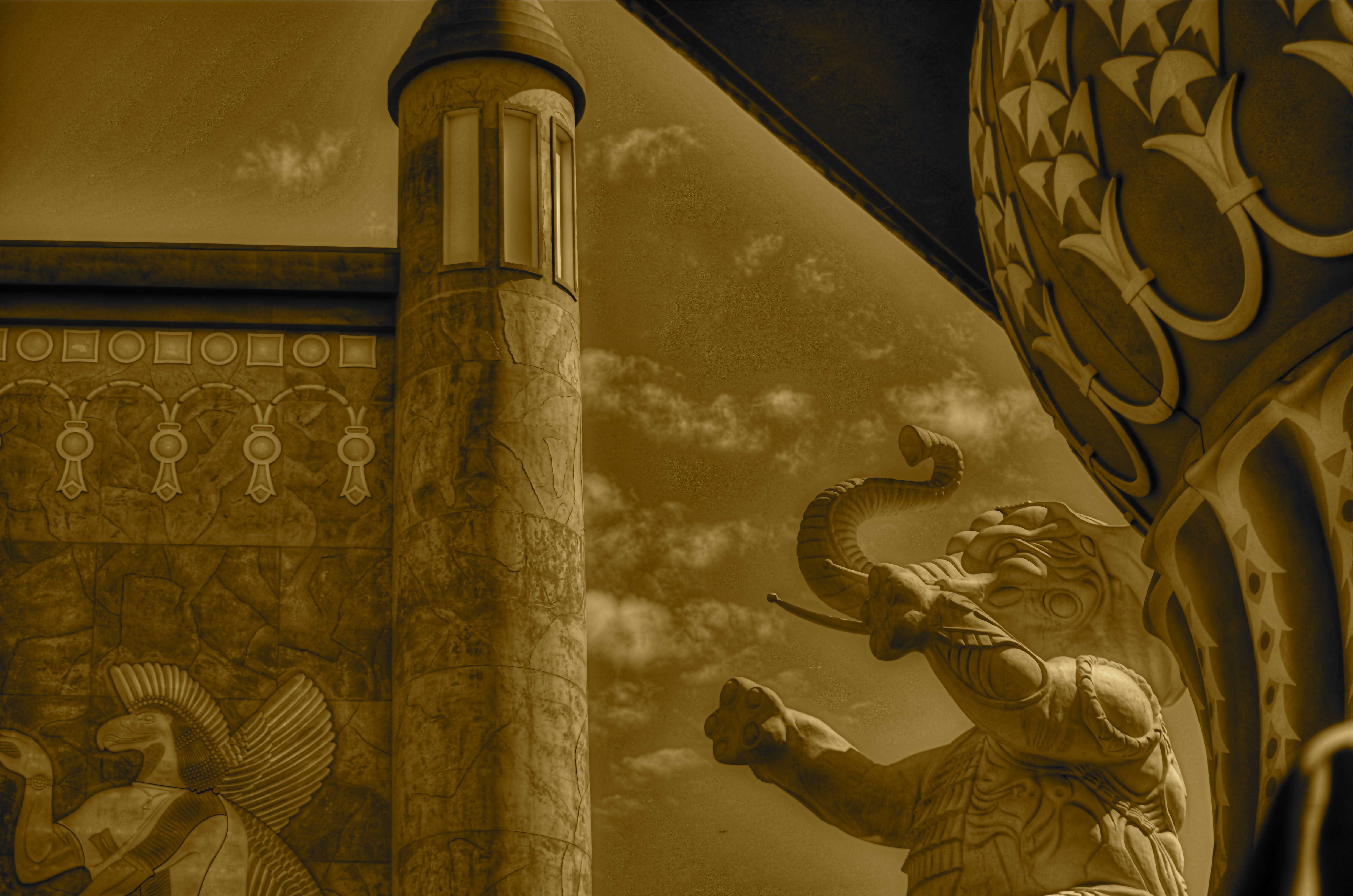

Reality check: a retail mall in Hollywood, doubling as a tribute to D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance. huh?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“You’re wrong. She is a phony. But on the other hand you’re right. She isn’t a phony because she’s a real phony. She believes all this crap she believes.”

—Truman Capote, Breakfast At Tiffany’s

THE ABOVE REFERENCE TO MISS HOLLY GOLIGHTLY, she of the powder room mad money, also applies very neatly to Hollywood, California. The official kingdom of fakery has been in the business of fabricating fantasy for so long, it actually treats its hokum as holy writ. Legends and lore become facts of life, at least our collective emotional life. Dorothy’s ruby slippers (even though they were originally silver) draw more attention than actual footwear from actual persons. Wax figures of imaginary characters are viewed by more people than will ever examine the real remains of wooly mammoths at the La Brea Tar Pits. And, when it comes to the starstruck mini-Vegas that is the nexus of Hollywood Boulevard and Highland Avenue, even a fake of a fake seems like a history lesson.

Hollywood and Highland is one grand, loud, crude note of Americana, from its out-of-work actors sweating away in Wookie suits in front of the Chinese theatre to its cheesy Oscar paperweights at the souvie shops. This small stretch of carnival, high-caloric garbage chow, and surreal retail is a version of a version, a recreation of a creation, a “real phony” rendition of cinema, defined by its resurrection of the great gate of Babylon, which anchors a multi-level mall adjacent to the Dolby Theatre, the place where all those genuine cheesy paperweights are given each year. The gate and the two enormous white elephants that flank it are a partial replica of D.W. Griffith’s enormous set for the fourth portion of his silent 1916 epic Intolerance. The full set had eight elephants, an enormous flight of descending stairs, two side wings, and a crowd that may have originally inspired the term “cast of thousands”. That’s how they did ’em back in the day, folks. No matte paintings, no CGI, no greenscreen. We gotta build Babylon on the back set, boys, and we only got a week to do it, so let’s get cracking.

The original set, which stood at Hollywood and Sunset, was, by 1919, a crumbling eyesore and, in the city’s opinion, a fire hazard. Griffith, who lost his shirt on Intolerance, didn’t have the money to demolish it himself, and eventually it fell into sufficient disrepair to make knocking it down more cost-effective. Hey, who knew that it might make a great backdrop for a Fossil store 2/3 of a century later? But Hollywood never balks at the task of making a fake of a fake, so the Highland Center’s ponderous pachyderms overlook throngs of visitors who wouldn’t know D.W. Griffith from Merv Griffin from Gryffindor, and the world spins on.

Photographing this strange monument is problematic since nearly all of it is crawling with people at any given moment. Forget about the fact that you’re trying to take a fake image of a fake version of a fake set. Just getting the thing framed up is an all-day walkabout. So, at the end of my quest, what did I do to immortalize this wondrous imposter? Took an HDR to ramp up an artificial sense of wear and tear, and slapped on some sepia tone.

But it’s okay, because I’m a real phony. I believe all the crap I believe.

Hooray for Hollywood.

CHANGE OF PLAN

Rainy day, dream away. Griffith Observatory under early overcast, 11/29/13. 1/160, f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

by MICHAEL PERKINS

VISUAL WONDERS, IN EVERY HOUR AND SEASON, ARE THE COMMON CURRENCY OF CALIFORNIA’S GRIFFITH OBSERVATORY. The setting for this marvelous facility, a breathtaking overlook of downtown Los Angeles, the Hollywood Hills, and the Pacific Ocean, will evoke a gasp from the most jaded traveler, and can frequently upstage the scientific wonders contained within its gleaming white Deco skin.

And when the light above the site’s vast expanse of sky fully asserts itself, that, photographically, trumps everything. For, at that moment, it doesn’t matter what you originally came to capture.

You’re going to want to be all about that light.

Upon my most recent visit to Griffith, the sky was dulled by a thick overcast and drenched by a slate-grey rain that had steadily dripped over the site since dawn. The walkways and common decks were nearly deserted throughout the day, chasing the park’s visitors inside since the opening of doors at noon. By around 3pm, a slow shift began, with stray shafts of sun beginning to seek fissures in the weakening cloud cover. Minute by minute, the dull puddles outside the telescope housing began to gleam; shadows tried to assert themselves beneath the umbrellas ringing the exterior of the cafeteria; the letters on the Hollywood sign started to warm like white embers; and people of all ages ventured slowly to the outside walkways.

The moment the light broke, Griffith’s common areas after the rain,11/29/13. 1/640 sec., f/5.6 (this image), f/6.3 (lower image), ISO 100, 35mm.

By just after 5 in the afternoon, the pattern had moved into a new category altogether. As the overcast began to break and scatter, creating one diffuser of the remaining sunlight, the fading day applied its own atmospheric softening. The combination of these two filtrations created an electric glow of light that flickered between white hot and warm, bathing the surrounding hillsides with explosive pastels and sharp contrasts. For photographers along the park site, the light had undoubtably become THE STORY. Yes the buildings are pretty, yes the view is marvelous. But look what the light is doing.

Like everyone else, I knew I was living moment-to-moment in a temporary, irresistible miracle. The rhythm became click-and-hope, click-and-pray.

And smiles for souvenirs, emblazoned on the faces of a hundred newly-minted Gene Kellys.

“Siiingin’ in the rainnnn…”

Related articles

HOLLYWOOD NIGHTS

Moonlight night around the poolside, only not really: a “day-for-night” shot taken at 5:17pm. 1/400 sec., f/18, ISO 100, 35mm, using a tungsten white balance.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TIME LIMITS US IN EVERY PHOTOGRAPHIC SITUATION: LIGHT HEMS US IN EVEN FURTHER. Of course, the history of photography is rife with people who refuse to just accept what time and nature feel like giving them. In fact, that refusal to settle is source of all the artistry. Too bright? Too bland? Wrong time of day? Hey, there’s an app for that. Or, more precisely, a work-around. Recently, I re-acquainted myself with one of the easiest, oldest, and more satisfying of these “cheats”, a solid, simple way to enhance the mood of any exterior image.

And to bend time… a little.

Same scene as above taken just seconds later, but with normal white balancing and settings of 1/250 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

It’s based on one of Hollywood’s long-standing budget-savers, a technique called day-for-night. For nearly a century, cinematographers have simulated nightfall while shooting in the daytime, simply by manipulating exposure or processing. Many of the movie sequences you see represented as “night” are, in fact, better lit than any “normal” night, unless you’re under a bright, full moon. Day-for-night allows objects to be more discernible than in “real” night because their illumination is actually coming from sunlight, albeit sunlight that’s been processed differently. Shadows are starker and it’s easier to highlight what you want to call attention to. It’s also a romantically warm blue instead of, well, black. It’s not a replication of reality. Like most cinematic effects, it’s a little bit better than real.

If you’re forced to approach your subject hours before sunset, or if you simply want to go for a different “feel” on a shot, this is a great shortcut. Even better, in the digital era, it’s embarrassingly easy to achieve: simple dial up a white balance that you’d normally use indoors to balance incandescent light. Use the popular “light bulb” icon or a tungsten setting. Indoors this actually helps compensate for cold, bluish tones, but, outside, it amps up the blue to a beautiful, warm degree, especially for the sky. Colors like reds and yellows remain, but under an azure hue.

The only other thing to play with is exposure. Shutter-speed wise, head for the high country

at anywhere from f/18 to 22, and shorten your exposure time to at least 1/250th of a second or shorter. Here again, digital is your friend, because you can do a lot of trial and error until you get the right mix of shadow and illumination. Hey, you’re Mickey Mouse with the wizard hat on here. Get the look you want. And don’t worry about it being “real”. You checked that coat at the door already, remember?

Added treats: you stay anchored at 100 ISO, so no noise. And, once you get your shot, the magic is almost completely in-camera. Little or no post-tweaking to do. What’s not to like?

I’m not saying that you’ll get a Pulitzer-winning, faux-night shot of the Eiffel Tower, but, if your tour bus is only giving you a quick hop-off to snap said tower at 2 in the afternoon, it might give you a fantasy look that makes up in mood what it lacks in truth.

It ain’t the entire quiver, just one more arrow.

Follow Michael Perkins at Twitter @MPnormaleye.