THIS IS DELICIOUS: WHAT’S IN IT?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE IMAGES THAT POSSESS AN UNDENIABLE TIMELESSNESS, as if, in looking at that particular photograph, you are simultaneously looking at every photograph ever taken, as if the creator has tapped into something unbound by time, a picture that could have been made by anyone, anywhere, anytime. Of course, as artists, we aspire to capture something, shall we say, eternal, even though we work very much in the moment. Those lucky incidents (miracles?) cast a spell upon the viewer, a delicate skein of magic which can only be ruptured by running our mouths.

In today’s technical milieu, in which we can make anything look like anything, from any time, in any style, we are becoming addicted to over-explaining how we got to the finish line. We caption. We asterisk. We jawbone endlessly about our techniques; why we chose them, what the wondrous recipe contains and how you can apply it to your own pictures. How ordinary. How soul-less. Are we artists or cookbook collectors? Hints at how to achieve this film emulation or that vintage look are, I suppose, a source of study for some. But images need to image. The power or impact of a photo needs, finally, to stand on its own. There may be some fascination in how various effects were achieved, but in the end, in a visual medium, that data load is just not that important.

It’s now so long since I made this picture that I would have to deliberately research my data to remind me how I did it. But I won’t be doing that. I don’t need to know what road I traveled to get here. I got here. There is nothing that pulling up all that information can tell me about whether the photo works. Of course, at the time, I had to be supremely concerned with what ingredients made up the soup. But harping on about it now, merely to act as a soft brag about my talents, is just creating more noise in a world that’s awash in it. There is a reason why magicians don’t explain how the rabbit got into the top hat. Let’s incline ourselves, in making images, toward wonder rather than technical blather.

MY MAINTENANCE YEAR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NOT ALL PROGRESS IS MEASURED MERELY IN FORWARD MOTION. The phrase “look how far we’ve come” is regularly used to indicated growth, when, in photography, as in many other ventures, the sentence “look how wide/deep we’ve expanded” may be just as important. Thus, at the close of a year such as the one I’ve just survived, my work with images isn’t best seen as a series of break-throughs or epiphanies as an attempt to refine or improve the existing areas of my knowledge that could use a good buffing-up.

The Skirball Cultural Center’s salute to the American Immigration experience, Los Angeles, 2025.

I came to this conclusion after reviewing the calendar year and finding few, if any, miraculously fresh things in the “done” basket, just more detailed ways of delivering the ideas I’ve already explored over many years. Part of this was my own compromised health, which, though temporary, definitely kept me in Emily Dickinson mode, confined to the house and dreaming of the picture opportunities left untouched just outside my window (Emily was a real whiz with a Rollieflex, as I recall). There were too many days I just couldn’t be “out among ’em”, which led me to work, instead, on a deeper dive into things I could work on without a lot of travel.

This led me to a couple of productive areas, including tackling the unexpectedly steep learning curve for a new lens (it takes a lot of work to make things appear effortless, ha), giving me time to enhance my approach to low-light situations (including new uses for Auto-ISO in my wildlife work), and to renew my continuing love affair with 50mm primes. During the times that I was more completely mobile, I found myself searching for visible measures of patriotism, from small marches to grand museum exhibits (see above). In the current season, it seemed only natural to turn my camera toward one of the most convulsive societal upheavals in my seventy-plus years on the planet, and, when I was more regularly out-of-doors, I made a special effort to capture that tension in-camera. As I said, this was a year of sinking deeper taproots into things I needed to improve rather than boldly going where no one has gone before, and I am trying to tell myself that that, too, is of value. Or so I hope.

THE LAND OF NO EXCUSES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

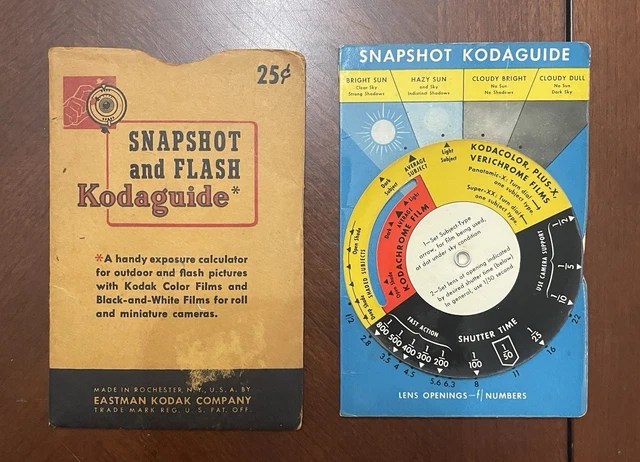

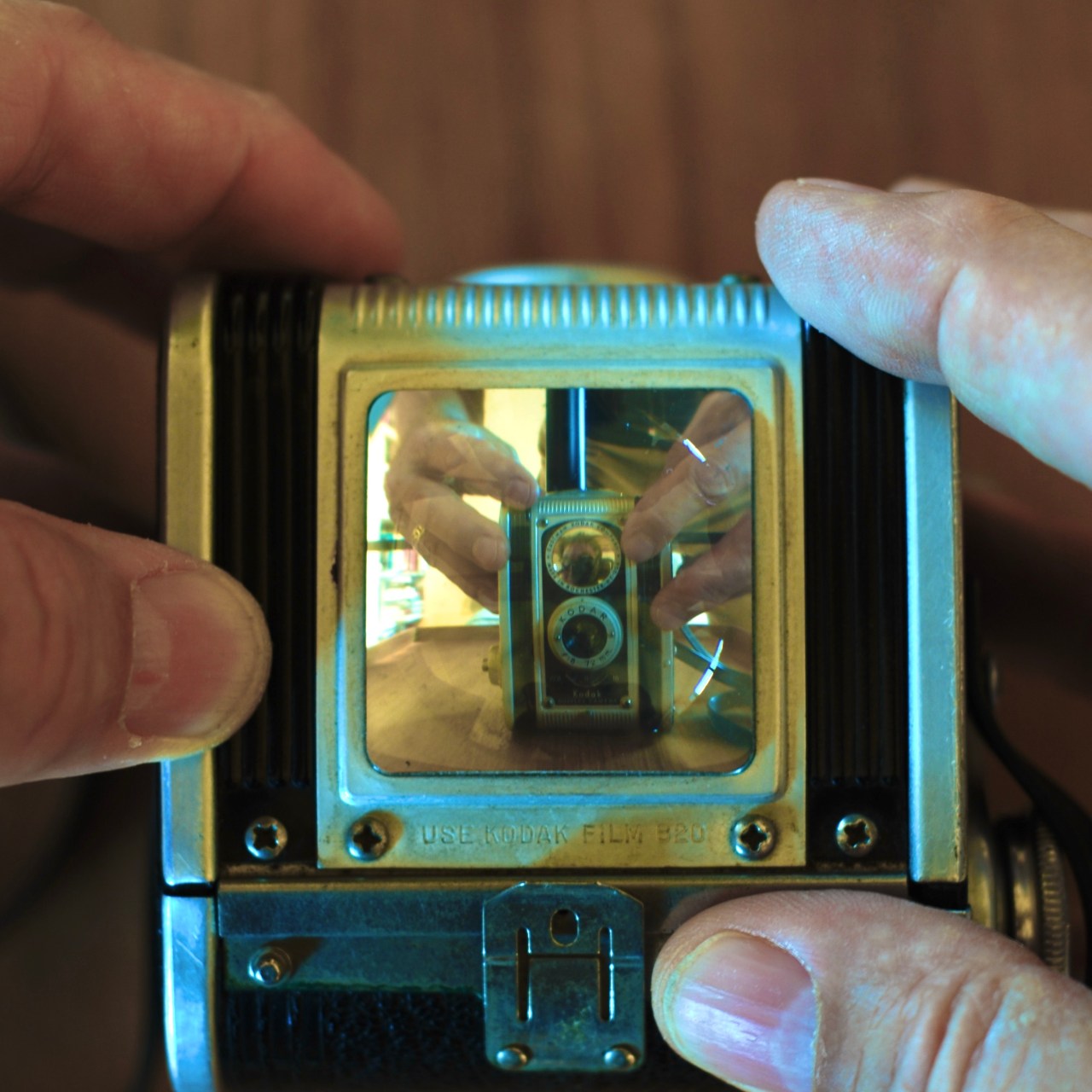

THE TIME IS FAST APPROACHING where most of the photographers in the world will have no personal memory of just how much technical skill once needed to be applied just to obtain a usable photograph. We are already a full generation removed from a world in which film had to be purchased, loaded, exposed, unloaded and processed before the results could be viewed. Also gone for most people is the careful budgeting of shots that had to be plotted so that snaps of a vacation could be captured within the span of 24 or 36 exposures, rather than the endless barrage of shots made typical in the digital age. And beyond all that lies an additional plethora of calculations, tools, aides, and attachments once enlisted in the great effort expended in making pictures look, well, effortless. These all speak not to the art but to the craft of photography, and, as they fade away for good, all we are left with is endless possibilities and greatly increased responsibility. Simply put, there is almost no excuse for making a bad image.

The little wonder you see here was produced by Eastman Kodak Company for generations, and was always tucked into my father’s shirt pocket for quick consultation before triggering the shutter. For shooters of his generation, taking a shot meant first solving a math problem. Composition and inspiration came in second or third after just being able to hack the science of it all. Many cameras had basic instructions for use or loading inscribed inside their covers, and every roll of film was accompanied by a flier on how to correctly expose that particular emulsion. The aforementioned Kodak also kept HOW TO MAKE GOOD PICTURES, its basic primer on photo techniques, in print for nearly sixty years. And then you also factor in the efforts of the true purists, those who chose to process their own film. The point is, the apparatus involved in being able to take the uncertainty out of photography is largely gone, with more responsive “serious” cameras and mobiles virtually guaranteeing a workable result every single time.

So why are there still so many awful, bland, uninteresting, insanely misconceived photos? Well, it could be because there is still a real limit to what cameras can do. Granted, they are better than ever at anticipating what we need in a given situation and trying to supply it. They are also incredible at protecting us against our own limited skills. But they cannot think. Or feel. Or, to be very hippy-dippy, dream. The best photographers are, in fact, dreamers, and it was not so long ago that our dreams were thwarted, or at least compromised, by our need to “master” the camera, to tame it as one might a wild stallion. Now, we no longer have to fight our gear to a draw. The craft aspect is largely gone. The art part remains. And that’s on us.

I WAS JUST IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD ANYWAY…

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CROOKS AREN’T THE ONLY PEOPLE WHO RETURN TO THE SCENE OF THE CRIME. Photographers have the same neurotic habit of going back to the place where things went wrong. Only, instead of a “crime”, it’s the scene of a picture that we (a) loused up the first time (b) loused up the second time, (c) might look better with a different camera/exposure/lens or (d) is just some infernal, unsatisfiable itch that we must scratch or go crazy.

This building is one such place. I don’t know why it is filed in my fevered brain under “unfinished business”, but it is.

This apartment block is just one street away from the home of a dear friend in central Los Angeles, so I have probably made the short pilgrimage to it for at at least ten years’ worth of visits. Part of its attraction is that it’s one of the only original Art Deco structures left in the neighborhood. Another part of it is the utter simplicity of its design, as is its clean teal tone. I’ve been snapping it for so long now that a complete folder of my collected shots of it could easily serve as a time-line on my own development as a photographer, as I’ve taken a crack at it through every phase, fad and infatuation I’ve endured over those ten years.

I’ve taken it with wide-angles and telephotos, primes manual lenses and fully automatic exposure. I’ve given it the lo-fi treatment with both cheap plastic and pricey Lensbaby art lenses. I’ve done full-on frontal shots of the entire building, distorted fisheye angles from the corners and sides, time exposures just after sunset with its windows all aglow and, as seen here as vertical slices designed to abstract it to pure shape. I think I’m done. However, I’ve said that many times before.

It’s frustrating enough to get a single pass at a place or subject, such as a snap of a tourist location you’ll never re-visit. It’s frustrating in a different way to have unlimited access to something that you can’t quite seem to nail, not matter how many swings you take. I was not blessed with a natural bent toward humility. However, thanks to photography, it’s closer to second nature for me. If I live long enough, I might just finish growing up. Or finally get The Picture of this wretched building.

BACK TO EDEN

The task I’m trying to achieve, above all, is to make you see.—-D.W. Griffith

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY YEAR OR SO, OVER THE NORMAL EYE’S FOURTEEN-YEAR JOURNEY, I tackle anew the task of explaining the choice of that particular name. That means proposing a kind of working definition for the word “normal”, or at least putting forth the reasoning behind my own use of it within these pages.

For me, to be “normal” is to operate within the first, natural state of something. And when it comes to the making of photographs, that means the first state of the human eye. The “factory setting” for your eye is observation, not merely “seeing”. As a new human being coming into the world, you don’t just believe what you see; you believe in excess of, even in spite of what you see. That which we call “factual” is fluid, colored by experience, and certainly not formed by data alone. Only after we leave childhood are we trained to think that are eyes are only to be used for documentation or recording, for evidentiary work. At that point, we stray from the “normal” state of our eyes, the vision we were equipped with, as a default, when we first came to be.

However, once you pick up a camera, you actually leave the plainly factual behind, since you are already utilizing a machine that, on its best day, can only generate an abstraction of “reality”. By making images with that machine, you are already weighted in favor of interpretation, of seeing past your senses. And that restores your ocular factory setting or default. Your soul, in effect, gets rebooted.

It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.—-Picasso

Pablo had the right dope: we have to unlearn the bad training, foisted upon us by the world, about what’s “important” to look at. We have to re-learn the ability to trust fancy. That is the only path to art. If our eyes were merely designed to make a visual document of the world, we would only have to take a single photography of any object on earth, as only one would be necessary. Instead, we honor sentences that begin with “the way I see it is..” We are moved by photographers with normal eyes. That’s what this venue is, and has always been, about. A return to Eden, if you will. A reassertion of innocence. To believe that what we have to say about the world is, indeed, normal. For us.

FITS AND (FALSE) STARTS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ERGONOMICS is defined as “the application of psychological and physiological principles to the engineering and design of products, processes and systems.” When it comes to photography, the term “good fit” is probably the simplest way to express this concept. Cameras engage the hands, the eye, and the mind with each click. The question to be asked of any camera then, is, “how is this machine helping me make better pictures with a minimum of fuss and delay?”

The term “human factors engineering” (HFE) is sometimes used instead of “ergonomics” and I actually like that phrase better, since it says exactly what the designer’s goal should be; making things so that they are easy to operate in an efficient and satisfying manner. So let’s apply that idea to the various dials, buttons and menu options on a camera, and where they are situated. Does your device cause you too many tasks per image in terms of calculating, reaching, holding, executing? Many of the most elegantly designed pieces of kit in photographic history have also been some of the worst nightmares when those stunning sketches leave the inventor’s table and enter the real world of shooting. And so, what makes a generally operational camera not work for you must be the primary consideration when you’re shopping, more so than features, price, or high marks from techie reviewers.

In a 2012 article called Camera Ergonomics, revised for 2023, a common operation done by a very popular model (name withheld) was outlined to illustrate the frustrating processes that were baked into the camera by its designers:

“When we want to operate the front control dial, there is not enough space for the right index finger to bear on it without moving the other fingers of the right hand out of the way, so we have to release our grip on the handle with the third or fourth fingers, move those fingers down the handle, move the index finger forward and down to the front dial, rotate it, move the index finger back up to the shutter button, release our grip with the third and fourth fingers, and move them back to their regular holding position. This is seven different actions, two of which involve moving the entire hand…”

Sadly, many of us simply make the adjustment in ourselves when presented with an obstacle placed in our path by the camera. We make ourselves fit the device instead of vice versa. This is madness. Any thinking review of a new camera should focus primarily on what it’s like to use the thing, because anything else simply builds extra, time-wasting, shot-missing junk into the process.

Never mind that cameras currently come loaded with enough tricks and toys that will never be fully used over their useful lifetimes, or that the snarl of intertwined option menus on many machines is a jungle all on its own. Take it down to the most basic and essential issue; if the camera literally requires you to contort your body beyond its natural functions just to take a picture, it is the device, not the human, which merits a re-design.

ON THE FACE OF IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE ALWAYS HAD A VIOLENT ALLERGIC REACTION TO PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO SPEAK IN ABSOLUTES, rigidly regulated by rules and procedures, especially as regards gear. Any opinion piece or analysis that contains the phrases “alway do” or “never do” have a perverse effect on me. It’s like telling Adam and Eve that they can eat from any tree in the garden except, you, know that one. It makes the apples on said tree start to seem like they might be the most delicious in the world.

Same with telling people that a set piece of kit or a certain approach will “always” result in a miraculous image. One thing that the digital era has achieved is the increasing rarity of this kind of guidance. In the film era, we were told in no uncertain terms what good and bad focus was, what constituted a “correct” composition. Today, we’re in more of an “anything goes” arena, with people finding freedom in a more experimental frame of mind. And one of the areas where this is most in evidence, since we are more fascinated by faces than ever before here in Selfie World, is in all types of portraiture.

Does this lens make by eye look too fat?

Formal studios used to dominate portrait work to such a degree (hey, we get out of class for an hour…it’s PICTURE DAY!) that a kind of holy writ of thought held sway on the “best” lenses to use to capture someone’s personality. Now, with an insane variety of apps packed in our pockets, the concept of portraiture has been freed from the photo mills of the past, as is the idea of how best to present human features. Whereas amateur photographers used to use a certain hunk of glass consistently for every kind of face, say something in the 85 to 105mm range, extreme wide-angles from 8 to 18mm are now just as much in use.

One of the reason for this shift is that cellphone cameras, at least basic ones, tend to shoot in the wider focal lengths that were once considered “wrong” or unflattering, since they can create distortion in the middle of the subject’s face depending on the distance. However, some people have used just this look to purposefully sculpt their facial contours, to play stretch-and-shrink with their given proportions in order to make their faces look longer or slimmer or to accentuate other elements. On the other end of the spectrum, zooms used to looked down upon by some for portraits because it could be harder to blur out backgrounds at smaller apertures, but now, since most digital images are really only a starting point ahead of post-snap tweaks anyway, even that problem can be solved more easily than in days past.

For years I heard primes in the 35-50mm range touted as the so-called “normal” lenses, since they were supposed to “see” the face at the same proportions as the human eye, or “normally”. But do I use them exclusively? Heck, I don’t use anything exclusively anymore. And neither does anyone else. The days of the didactic “never do” and “always do” tutorials are long gone, with a great portrait defined by nothing more than your own satisfaction. Finally.

TAKING ONE FROM THE TEAM

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS A CERTAIN DIVINE IMMUNITY attached to photographers who are lucky enough to remain amateurs, or, for those who do turn pro, the ability to remember how to shoot with an amateur brain. There used to be a cleanly defined line between people who had to make pictures for a living (under deadline, enslaved to editors, for the marketplace) and those who could never dream of doing so, but who might work every bit as hard just pleasing themselves. However, social media, with its ability to suddenly confer ( or cruelly withhold )sudden celebrity, has recently blurred this line between the careerists and the tinkerers. Now, even when we are making pictures for “no one”, we seem to be making pictures for everyone, anyway.

It’s getting harder to create a photograph in a feedback vacuum, to shoot without even a thought of how well a picture will be received. The tyranny of the new “like” and “fave” marketplace can riddle a photographer with doubt, gently bending his/her work to what might meet with the most approving eyes. In many ways, this new world is even more unforgiving, for amateurs, than the dreaded editing desk was for the professionals.

It’s more of a challenge than it used to be, these days, to allow oneself to make a picture like this one. The subject isn’t startling, or even especially unique, except to me. The composition is deliberately formalized, and so can’t qualify as avant-garde. The final shot, the product of a double exposure and some minimal color and contrast tweaking, is neither purely realistic nor challengingly abstract. In short, this picture is nothing in particular, except that it’s mine, made my way, for my own approval. I don’t have to worry that, as Frank Zappa would say, it suffers from N.C.P. (No Commercial Potential).

Any artist that is forced to produce for the popular market has two struggles: to achieve his vision and to package it for consumption by others. It’s THE tightrope act of a lifetime for photographers, with the amateurs envious of the pros’ access and the pros jealous of the casual snapper’s freedom. I have made my daily bread by a number of means over a lifetime, mostly under the gun of deadlines and editors in the print or electronic media, and so, while I have seldom earned a paycheck specifically with a camera, I have empathy for those who do.

There are things about working as a paid shooter that I will never have to endure, or suffer, and I know that. However, in the 21st century, even being an amateur is beginning to take on the haggard hassle that only used to accrue to the Guy Doing It For A Living. That is why the bigger fight in becoming a photographer is the mastery over one’s self rather than the perfection of mere technique. Sports and every other fun pursuit in our world has shown what happens when everything gets too serious and the meaningful meaninglessness goes out of something. In our art, we are being forced, more and more, to do everything for social reasons, to “take one for the team”. However, it is the pictures that you take from the team that truly remain your own, and that you will treasure the most over a lifetime.

LOVED INTO LONGEVITY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

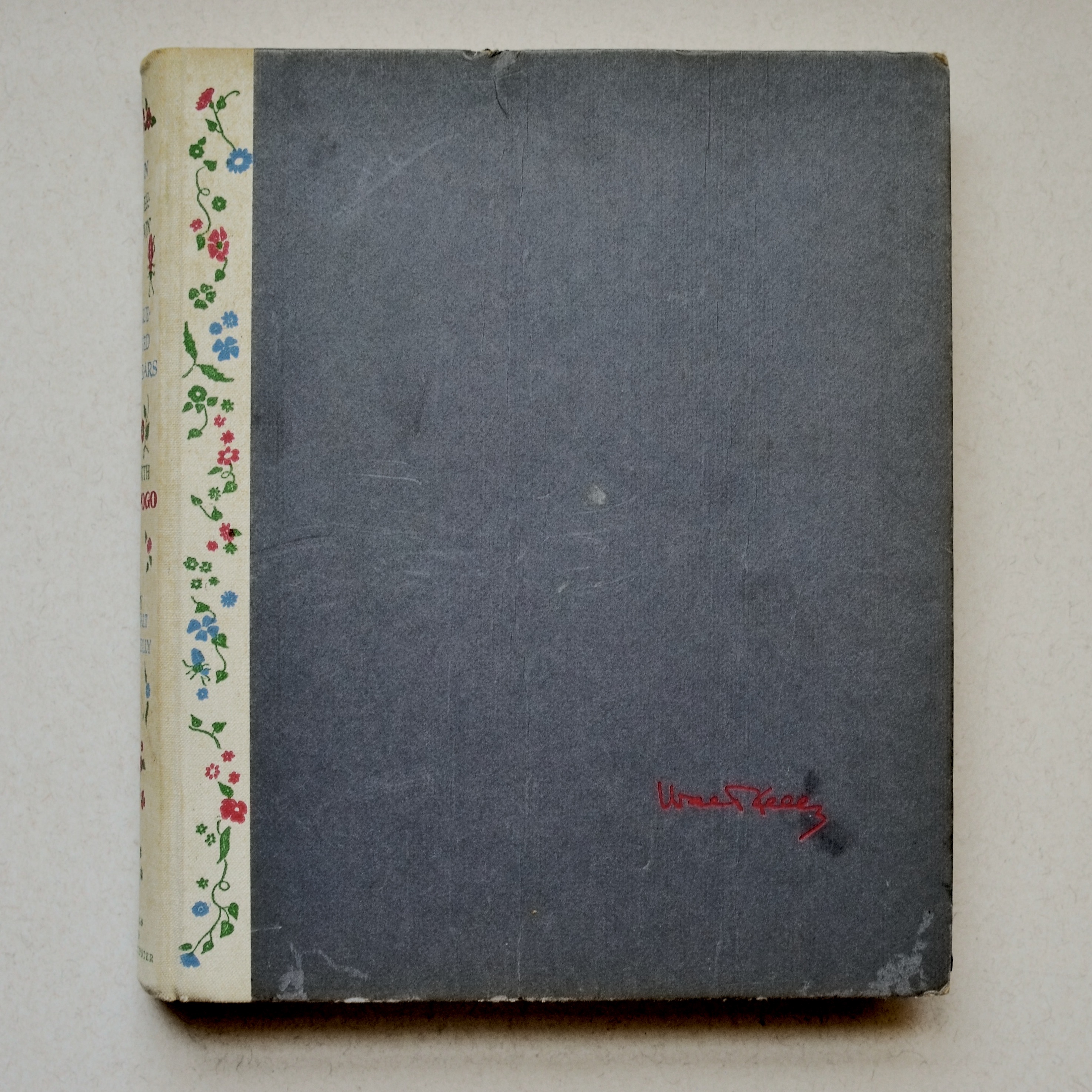

SO MUCH OF THE GREATER WORLD SEEMS SO PERISHABLE under our present Great Hibernation that one’s mind goes naturally to things of more lasting value. The more that contemporary concepts of “permanence” vanish like smoke, the more the photographer in me values the artifacts of a life that still remain close at hand. Access to the fuller world is often denied me these days, but, here, inside the compound, there is a renewed opportunity to visually reassess the things I have carried with me over a lifetime.

This has led me to try to create what you might call formal photographic “portraits” of various ephemera around the house, from weathered old coats to favorite records to…books. For me, a person who has entertained a collector’s fetish with so many kinds of playthings and pastimes over the years, everything always seems to come back to books. The printed word, and the physical packages in which it came, harnessed my passion before music, before photography, before even romantic love. And, if we’re talking about a consistent source of comfort, books have acted as one of the most permanent and reliable anchors to earlier versions of myself. I leap between covers, and I vanish, emerging re-centered, fuller and finer than I was before the plunge.

In trying to photograph the oldest surviving book in my collection, I found a lot of techniques left something visually unsaid, delivering images that were too cosmetically clean, too charming. The book you see here has been with me in high times and low since 1963. It was probably the first hardback book that was truly mine, not one just plucked out of my parents’ library. For my picture, it needed to look traveled, well explored. It needed the historical gravitas of a few creases and stains, to look like a book that was important enough to be revisited and revered over a lifetime. After several attempts that looked, well, flat to me, I decided to go into my old trick bag and shoot it as an HDR. I had not used the technique for a while, since the acuity of current camera sensors has improved to the point where shooting and blending several bracketed exposures just to reproduce the full dynamic range of tones from dark to light was now as easy as squeezing off a snapshot. But in the case of my library’s longevity leader, I needed the over-accentuated detail that sometimes turned me (and others) against HDR: a look which would record and underscore every defect and scar, freeing them to speak a little louder. Another thing that argued for the technique: years prior, I had made a picture of my wife’s old 45 rpm record storage case, an item similarly, vigorously loved. HDR would deliver the warts-and-all portrayal I was seeking.

In the end I eschewed the full-tilt effect in favor of a milder blend called tone compression, boosting the detail but stopping short of making things too surreal. Finally, I had a picture that made the book look as if it had actually been used, rather than flawlessly archived. I had loved that book into longevity, and now, like the proud lines of survival etched on the face of a human subject, the tome was capable of fully flaunting its flaws.

Fabulously.

TO-DO’s AND TO-DONT’S

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE EASIEST THINGS TO LEARN ABOUT IN PHOTOGRAPHY, apparently, is what you’re doing wrong, or so a casual stroll through the Googleweb would suggest. The internet is lots of things, but starved for opinions it ain’t, and so one of the fattest search yields you’ll find online consists of lists, endless in number, on how we are falling short as shooters. You may have sought them out yourself: “Ten most common mistakes”, “the beginner errors everyone makes” “twenty things not to do with your pictures” and so on into the night, rosters of failure and shame compiled by everyone from prominent pros to the village idiot. Actually, that’s unfair. Likely the village idiot is having too much fun taking photos to worry a lot about whether he’s doing it right. As a lifelong village idiot, I can attest that it takes one to know one.

Many of the sins, both venial and mortal, that make up these “to-don’t” lists are of a purely technical nature, such as picking the right aperture or making sure that you haven’t posed a subject in such a way as to make it appear that a hibiscus is sprouting out of the top of his head. Surprisingly, there are fewer suggestions about composure…what makes it stark or busy, what makes it fail to engage or confusing to “read”…than you’d suppose. Almost none of these lists actually address ideas or motivation. And so I mainly regard all such lists with a bit of an arched eyebrow, for the simple reason that they are so very practical. Practical and art are not often on speaking terms.

Orson Welles, a directorial virgin when he arrived in Hollywood to make Citizen Kane, was told by his cinematographer Gregg Toland that there was nothing about shooting a picture that couldn’t be taught in a weekend. Welles’ verdict: Toland was right. Still photography is similar: the mechanics of merely getting a picture into the box are not like the procedures for splitting the atom: much of the moves we make to make an image are but variations on the moves we’e always made, and even without formal instruction, digital has made the learning curve so short that you can muster (if not master) the basics in a few days. It’s what to do with all those technical tips that separates the men/women from the boys/girls, and the endless online (or printed) to-don’t lists don’t even address that amidst all their edicts on lighting and lenses. Because they can’t. Because it can’t be taught like the steps of changing your oil can be taught. It can be learned, but only from yourself. Certainly, if you can’t see, you can still shoot. It just won’t matter that you did, that’s all.

The reason arbitrary rules don’t work with art is because art works best when rules are broken. If all we had to do with a camera was faithfully record light and dark, we would eventually, with practice, all have the same level of excellence. But we don’t. And we can’t. Sometimes a picture just works, despite some line judge saying that it’s too dark, too blurry, or too busy. And if a picture does not transmit your passion to someone else, then all the technical excellence in the world can’t make it connect any better. Why don’t all the do-and-don’t lists talk about motivation, or intention, or just the habit of shooting mindfully? Because that is a matter of mystery beyond measurement. A picture is built, not taken. It happens within the eye and mind of the shooter, and sometimes leapfrogs over all the correct techniques to arrive at a result that is too personal to be contained in a rule book.

WAITING IN THE WINGS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS ARE DOCUMENTS THAT ARE SHAPED BY PERFORMANCES. That sentence, at this point in history, seems so obvious that it seems superfluous to even state. But it wasn’t always seen that way.

The camera, at its creation, was feared and reviled as the very opposite of an art instrument, characterized as a soulless machine that recorded without seeing, without interpreting. Whereas the painter filtered the world through the experiences and emotions coursing through his heart and mind, the photographer just held a box, and the box merely measured light. The box was seen as a cold, lifeless thing could never render a breathing, living world. Could it?

But the box, it turned out, was never merely held, never just pointed, and its eye never merely etched data on a plate. How it was held, what it was pointed at made a crucial, measurable difference. What it framed and what it excluded made other differences. And then there was the eye of the thing. Turned out, even that glassy orb could, in time, be adjusted, made more sensitive, more attentive. In fact, photography was becoming, after the science was scoped out, a performer’s medium, no less than a person holding an instrument called a paintbrush, or striking an instrument called a piano. There was an expectation, an anxiety involved in the act, a desire to get it right. Each single photograph was subtlely different from all others, and the difference was in the nature of the performance.

I go through this meditation (or one like it) whenever I am on the eve of tackling a photographic subject that has eluded me for a long period of time. As you read this, I’m only days away from making a pilgrimage of sorts to such a subject, something that will be hard to re-visit in the future, and for which a lot of very fast, do-or-die decisions will be made in the moment. Well, do-or-die is a little dramatic: there is, after all, nothing really important on the line here. The subject matter doesn’t involve a breaking news event, nor will my success or failure in bringing back the pictures I want have any impact on life as we know it.

I just want to get it right.

The image seen here is of an access gate that is as close as I have ever gotten to my subject in the past. It is also the least beautiful feature of said subject, hence my annoying case of nerves.

My anxiety, though truly laughable/pathetic, accompanies things that I care about, and maybe that’s a good definition of art….an attempt to make sense of the things we care about. Just pointing a box cannot produce that feeling. But photography has never really been about the box, has it?

THE DREYFUS REFLEX

By MICHAEL PERKINS

This is important. This means something….

Roy Neary, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind

I HAVE NEVER TRIED TO SCULPT THE MASHED POTATOES FROM OUR NIGHTLY DINNER into a replica of Devil’s Tower, but, as a photographer, I have experienced plenty of Roy Neary “a-ha” moments, marveling as a seemingly bland tableau pops into something very, very different in my mind’s eye. It’s the transformational moment that, when it occurs, justifies all of the sit-and-wait and close-but-no-cigar moments associated with making pictures. It is so invigorating that it re-enlists the weariest of us for yet one more tour of duty. Even the chance for experiencing a Roy Neary moment, what I call the Dreyfus Reflex, will shore up our courage and refresh our dedication. Hey, magic happened that one other time, we say. It might happen again.

But learning to see creatively is not merely a matter of being willing to receive a visual message from the great beyond. Seeing is an exercise, no less than a push-up or a jumping jack. It’s a matter of perfecting yourself as a receptacle, as a kind of pipe through which ideas can flow freely. The pipe has to be constantly widened and re-opened, and the exercise of learning to see ensures that, once an idea is at the entry point to the pipe, its path is unobstructed. Thus, the photographic concept is not coming from you so much as it is flowing through you. Learning to see photographically means, then, being “open” to a perception that, without practice, might never become apparent, but which, having become so, urges a photograph.

It means, in a sense, getting out of your own way.

Going back to our Close Encounters metaphor, Roy doesn’t start out thinking his dinner spuds resemble a mountain top. He gradually learns to accommodate ideas that are so un-obvious to everyone else that he seems crazy. Effectively, Roy has become an artist, in that he can look at one thing and see something beyond its mere surface appearance. In that moment, he is every poet, every novelist, every painter, and, yes, every photographer who ever lived. Similarly, any subject matter, such as the stalk of wheat seen here, can take on endless new identities, once we’ve become comfortable with it being more than one thing, or one version of a thing.

I once had a friend tell me that his favorite compliment as a photographer occurred when he was comparing pictures that he and a friend had taken from the very same trip, passing by identical sites and locations. “Where did you see that??” his companion remarked, indicating that while the two men’s sets of eyes were physically pointed in many of the same directions. they had come away with vastly different impressions. Does this process make one set of pictures “better” than another? Certainly not. But it does illustrate that there is more than one level of seeing, so that, even if my friend were to visit all those places alone, on different days, very different things would emerge in the pictures from varying shoots. What accounts for this variance? The light and the subject could be made to match: the gear and its settings could be replicated: even the precise time of day could be re-created, and yet the pictures of the same things by the same person would probably contrast noticeably with each other. And knowing all of that, when you set out as a photographer, means you’re aware of, and eager to exploit, the Dreyfus Reflex. What you see is just the first step of the journey: how you see it determines where the journey will eventually lead.

THEN AGAIN, WHAT DO I KNOW, ANYWAY?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOOT ENOUGH PHOTOGRAPHS AND YOU’LL ESTABLISH SOME KIND OF STANDARD of acceptability for your images….the inevitable “keeper” and “failure” piles by which we measure our successes (or lack thereof).

Now, we could fill pages with reflections on just how rational we all are (or aren’t) when it comes to editing ourselves. It’s a learned skill, one that’s practically a religion to some and a virtually unknown process to others. Be that as it may. Let’s assume for the purposes of this exercise that we are all honest, conscientious and humble when it comes to dividing our pictures into wins and losses. Even granting us all that wisdom, we are often less expert about whether a photograph is “worthy” than we think we are. You’d think that no one would know whether we took a bad image that we ourselves. But you’d be wrong, and often, wrong by a country mile.

Just as we are never so purely objective that we can be certain that we’ve generated a masterpiece, we can be just as unreliable in declaring our duds. I was reminded of that recently.

I have a lot of reasons to regard a given picture as “failed”. Some have to do with their effectiveness as narratives. Some I disdain because they’re nothing more than the faithful execution of a flawed idea. But the pictures of mine that the waste can catches the most of are simple technical botches….pure errors in doing. I’m old enough to hold certain rules of composition, exposure or focus as sacred, and I’m quick to dump any image that contravenes those laws.

That’s why the picture you see here was originally something I had intended to hide from the mother of the manic young man in the foreground. I had attempted, one afternoon, to use a manual focus lens to track four very energetic boys, and in one shot their ringleader had made a sudden lunge at the camera that threw him into blur. Seemed like a simple call. I had blown the shot, and I was naturally eager to show his folks only my best work.

But the impact of the picture on the boy’s family was much more positive. Blurry or not, the picture captured something very true about the boy. Call it zest, enthusiasm, even a little craziness, but this frame was, to them, more “like him” than many of the more conventional shots I had originally chosen to show them. The real-ness of his face had, for his family, redeemed the purely operational imperfection that so offended me. To put it another way, my “wait, I can do it better” was their “this is fine just as it is.” Sadly, it was my wife who brought me to my senses and convinced me to move it to the “keeper” pile.

Which circles back to my first point. None of us absolutely know what our best pictures are. We do absolutely know the ones that connect to various audiences, but that may be a completely different pile of images from the ones we label as “right”. Passing or failing a photo largely on technical grounds would, over history, disqualify many of the most important pictures ever made. We have all emotionally loved things that our logical minds might regard as having fallen short. But, in photography as in all other arts, we’re often fortunate that logic is not the sole yardstick.

MY WHITE WHALE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PERHAPS THE GREATEST SINGLE MOTIVATOR, FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS, is the eternal attempt to narrow the gap between what is seen and what can be shown, a permanent sense of one’s pictures coming up short, doomed to mere actuality versus the grand visions dancing in our heads. We shoot, we lament having “missed it”, and we shoot again. Lather, rinse, repeat.

I’ve written before, here, on the most frustrating, if tantalizing, subjects within that overall challenge….scenes or objects that we are free to repeatedly, endlessly re-shoot in hopes of “getting it right”, chasing the same things year after year, camera after camera, lens after lens, like Ahab chasing the White Whale round the world’s oceans.

These inexhaustible things are usually a staple of our immediate environment, part of our daily drives or walks, our standard routines. The maddening thing is that such hyper-familiar things should, eventually, submit to our art, should finally be captured in some final, completed fashion. But, in many cases, they remain studies, rehearsals, sketches. Unfinished business.

The tree you see here is one of my personal White Whales. I must drive past it at least five times a week, mostly in a quick glimpse out the window of my car. I have seen it in every season, every type of light, every mood filter within my own head. I have thrilled as it billowed to its fullest flower and mourned when groundskeepers judged it too wild and rangy, pruning it in ways that threaten, for a time, to obliterate the tree’s identity. I have parked and stepped over to pay it closer tribute with this lens or that, shooting full-on, in macro mode along trunk grain or branch lines, in fisheye, sharp detail, selective focus, monochrome and color. Each rendition gives me something; no one image delivers all.

Your particular tree (or house, or face, or river, or..) can both energize and enervate your photography. Even your failures can be seen as a prelude to inevitable success, as rehearsals toward a final, finessed performance. That feeling of being on a conveyor belt to Paradise is the essence of art, with the journey teasing us that there is, actually, a destination. If you have no White Whale of your own, I recommend heading out to sea, and scanning the horizon until you see one spout. Then grab a camera and try to tell someone about it.

STOLEN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NO DOUBT WEARY OF QUESTIONS about the secret of his photographic technique, the late Lars Tunbjork once told an interviewer, “I try to take photos like an alien”, a statement which strikes me as the perfect description of the shooter’s viewpoint. We are steeped in our own humanity: we are swept along in its tidal swell. But being part of all life gives us a skewed perspective as commentators. Striving to renounce our membership, to become The Outsider, is an art in itself. And certain pictures simply can’t be made without it.

Observing a scene as if one were an “alien”, as if we were freshly arrived on a scene which possessed nothing familiar to us, forces us to make unbiased, instantaneous evaluations of what is picture-worthy, not from our memory or habit, but from instincts, even raw guesses. Like E.T., harvesting earth plants for the purpose of study, we are placing ourselves into the viewpoint of a Columbus or an Armstrong. If we succeed, our perspective is truly that of someone Who Has Never Been Before. These small stolen instants of what one photographer called the flash of perception free us, momentarily, from what we’ve learned or assumed over a lifetime of experience. They allow us to shoot things we don’t pause to understand or contexualize. We feel that something ought to be a picture, and so it becomes one.

Tunbjork often took shots of randomly selected people in office environments doing the daily mundane tasks of making a living. The pictures were certainly “real” in a sense, and can, in fact, convey the feeling that we are getting our first (fresh?) look at things so ordinary that they have become invisible. Just as in the case of the shot seen here, snapped as I took a shortcut through a busy restaurant, the sensation can be that we have just happened upon something previously hidden: a conversation, a short relaxed break, a backstage glimpse. We are intruding into a place where we normally are not admitted. We are stealing. Hopefully with a tale that, later, back on the mother ship, we can share with our fellow aliens.

BINGE / PURGE

I AM STILL IN PAIN, several days after the most aggressive photographic housecleaning I’ve endured in years, the ruthless removal of years of deadwood from a photo-sharing site on which I’ve parked way, way too many wayward pictures. This was, finally, the week to toss away the old moose head in the attic, the day to tearfully admit that you no longer fit into your varsity jersey. Hail and farewell, parting is such sweet sorrow. Goodbye and good riddance.

OVERHEARD DURING MY EDITING/DELETING PROCESS

Oh, My Gawd…

What even is that?

Well, that certainly didn’t work…..

Nothing wrong with this one…..except the lighting, aperture, and composition…

Seriously, what the hell is that?

Lots of this concentrated cringing over pix of yesteryear speaks to my old acronym SLAGIATT, or Seemed Like A Good Idea At The Time, the simple truth that what you believe is profound at the time of the shutter click will strike you as reeking fish wrap several miles down the pike. We do outgrow, update, and disown old ideas, hopefully replacing them with better ones.

To take it a bit further, if a significant number of your old images don’t make you want to reach for the bilge bucket, one of two things is true. (1) You are already God’s messenger, the one true Messiah of photography (unlikely), or (2) you are so mired in habit and false comfort that the way you shoot is the way you always shot and the way you will always shoot. Given those choices, it may be preferable to regard at least some of one’s work the way Jack Nicholson’s Joker riffed through Vicki Vale’s portfolio, i.e, “crap…..crap….crap…” It hurts, but it’s healthy.

Every binge must have a purge, and the gluttonous output of the digital age guarantees one sure truth: they can’t all be gems. I hate having to disown my kids as much as the next shooter, but part of learning is learning to fail, admitting that at least some of those kids will never Get Into A Good School, Settle Down With Someone Nice, and Start Giving Us Some Grandchildren. If for no other reason than to help us know excellence when we see it, we need to be able to fearlessly label all the loves we have lost.

RIDING THE SLIDER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MUST–HAVES during the golden age of component stereo was the graphic equalizer, a panel on the front of many hi-fi receivers that divvied up the audible spectrum into five zones, allowing the discriminating audiophile to create a custom low-midrange-hi mix of frequencies by adjusting each zone’s vertical slider switch. It gave a clear representation of the desired fidelity curve. It was visual. It was visceral. Most importantly, it was cool, man.

The “slider” is also, for me, a frame of reference for my photography, since it gives me a mental picture of where I’m at along the track from work that’s left-brained (precision-driven, analytical) and right-brained (instinctual, reactive, emotional). The slider almost never travels to either extreme in the making of pictures, but veers closer to one or the other in a custom e.q.’d mix between rational control and total abandon. This is becoming more common with photographers in general than at any time in the past. When it came to crafting an image, we almost always asked about the how of things. Now many more of us also ask about the why.

The above image is illustrative of this balancing act. In walking behind the two women emerging from a forest at the end of their dog walk, I was never going to have a lot of time to formally set up any one shot…..not unless I was willing to interrupt the ladies’ together time, which seemed counter-intuitive at best. Optically, I was shooting with a selective-focus lens, designed to be sharp at the center, then progressively softer at the edges. Additionally, I decided to under-expose both women, eliminating all detail and reducing them to silhouettes. This meant that I had to wait until they were fairly centered in the clearing at the edge of the woods, one of the only reference points I would have for sharp focus, the backlighting of their forms, and any suggestion of depth.

And so you have a shot which is neither all-rational nor all-instinctual but a mixture of the two, the slider’s mid-point between preparation and improvisation. Total adherence to the left brain can produce shots which are technically precise but emotionally sterile. Working too much on the right side can yield pictures that are chaotic or random. Learning to jockey the slider is at least as important a skill as either composition or conception.

MAKE IT SO

I’ve been photographing this for years, and I still don’t know what I think about it. Needs more work….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN PHOTOGRAPHY IS PURELY REPORTORIAL, as it is in journalism or documentation, it sticks pretty close to the accepted state of the world. It tries to depict things plainly and without comment; it delineates and defines; it shows us the true dimensions of events.

But when the same technology is used interpretively, there is no absolute “real”, no pure authenticity, other than what we choose to show. It is in re-purposing the world visually, shaping and framing it as we choose, that we can confer meaning on it pretty much at our whim. That’s where the “art” part comes into what would otherwise be a merely technical measurement of light. We not only choose our subject….we set the conversation about it. Simply stated, what you shoot is about whatever you decide it’s about.

Even with hyper-familiar objects, things seen and re-seen to the point that they are iconic (think Empire State Building) images can re-set the way we take those objects in. And, in the case of what I like to call “found objects”, such as the image seen at the top, the photographer is completely unfettered. If your viewer’s eye has no prior mental association with something, you’re writing on a blank sheet of paper. You can completely dictate the terms of engagement, imbuing it with either clarity or mystery, simplicity or symbolism.

I have always been flat-out floored by photographs that take me on a journey. Those who can conjure such adventures are the true magicians of the craft. And that’s what I chose to play in this arena over a lifetime. Because, when photography liberates itself from mere reality, it soars like no other art.

INCONVENIENT CONVENIENCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE LONG SINCE ABANDONED THE TASK OF CALCULATING HOW MANY DIGITAL IMAGES ARE CREATED every second of every day. The numbers are so huge as to be meaningless by this time, as the post-film revolution has removed most of the barriers that once kept people from (a) taking acceptable images or (b) doing so quickly. The global glut of photographs can never again be held in check by the higher failure rate, longer turnaround time, or technical intimidation of film.

Now we have to figure out if that’s always a good thing.

Back in the 1800’s. Photography was 95% technical sweat and 5% artistry. Two-minute exposures, primitive lenses and chancey processing techniques made image-making a chore, a task only suited to the dedicated tinkerer. The creation of cheap, reliable cameras around the turn of the 20th century tilted the sweat/artistry ratio a lot closer to, say, 60/40, amping up the number of users by millions, but still making it pretty easy to muck up a shot and rack up a ton of cost.

You know the rest. Making basic photographs is now basically instantaneous, making for shorter and shorter prep times before clicking the shutter. After all, the camera is good enough to compensate for most of our errors, and, more importantly, able to replicate professional results for people who are not professionals in any sense of the word. That translates to billions of pictures taken very, very quickly, with none of the stop-and-think deliberation that was baked into the film era.

We took longer to make a picture back in the day because we were hemmed in by the mechanics of the process. But, in that forced slowing, we automatically paid more active attention to the planning of a greater proportion of our shots. Of course, even in the old days, we cranked out millions of lousy pictures, but, if we were intent on making great ones, the process required us to slow down and think. We didn’t take 300 pictures over a weekend, 150 of them completely dispensable, nor did we record thirty “takes” of Junior blowing out his birthday candles. Worse, the age’s compulsive urge to share, rather than to edit, has also contributed to the flood tide of photo-litter that is our present reality.

If we are to regard photography as an art, then we have to judge it by more than just its convenience or speed. Both are great perks but both can actually erode the deliberation process needed to make something great. There are no short cuts to elegance or eloquence. Slow yourself up. Reject some ideas, and keep others to execute and refine. Learn to tell yourself “no”.

There is an old joke about an airpline pilot getting on the intercom and telling the passengers that he’s “hopelessly lost, but making great time”. Let’s not make pictures like that.

LOVE IS FOR LOSERS

Perfection is not a “product”; it’s a process.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST REPEATED TROPES IN PHOTOGRAPHIC INSTRUCTION in recent years has been some variant on the “there are no rules” theme, as if all of image-making were some miraculous hybrid of instinct and chance. And while I certainly applaud an attitude of flexibility when it comes to artistic expression, and even allowing for personal preferences for baseline techniques or practices, I would assert that, for nearly all photographers, there is one immutable law, and that is, simply, to allow yourself the opportunity to fail.

Failure is the cheapest and most lasting of educational building blocks. No art happens out of a natural superabundance of talent or taste: it has to be nurtured through the refinement of negative feedback. Even the most advanced AI devices feed off of bad data; evaluating errors, filtering them out, re-designing systems to reject those errors in future iterations. Failure in photography, defined here as “making bad pictures”, is the only correct path to making good ones. There is no technical advancement or ideal toy that can short-cut this process. You simply have to put in the time.

This is means learning to love your losers, to, in fact, have a particular gratitude for the shots you blow. Just as we lament over other mistakes we’ve made in our lives, we naturally linger over our artistic miscalcuations. The mis-read light. The fouled focus. The Compositions From Hell. The gap between what we could see and what we could induce our camera to see. And, most significantly, our own ignorance or life inexperience. Mistakes make us questions things in a way that successes seldom do.

A picture doesn’t even have to be a flat-out flop to gnaw at us, to demand re-takes and re-thinks, as seen in the image above, which neither completely delights or disgusts me, but certainly haunts me. The near misses can sometimes nag us as mercilessly as the missed-by-a-miles. More aggravating still is the fact that some of the very things that drive us mad will totally skate past the casual observer, or even appear to them to be “just fine”. Happily, as we develop, we learn to trust our own eye and dismiss everyone else’s as, well, irrelevant. Buying a more expensive camera, trying to “go with the flow”, following trends….nothing can compete with the slow, gradual, agonizing, and eventually gratifying process of snapping a lot of duds and changing course as we digest what went wrong until the problem is addressed.

The study of photography is fat with experts who swear it’s all about a whole bunch of rules on one end and people on the other extreme who declare that rules are meaningless. The real truth, your truth, is somewhere in between those two poles. But believe this: there is no substitute, formal or otherwise, for doing your homework, loving your losers as if they were wayward children, and working honestly to bring them right.

Share this:

March 28, 2021 | Categories: Uncategorized | Tags: Commentary, Composition, Technique | Leave a comment