NO SECOND ACT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS SOMETHING TRAGIC, AND CONFOUNDING, in America’s longstanding reluctance to re-use and re-purpose its historic infrastructure. This ever-young nation seems to have an allergic reaction to preservation, as if the physical artifacts of its heritage contained some kind of dread plague. As a consequence, buildings that have figured most prominently in the story of our nation’s amazing evolution fall…. first to neglect, then to the wrecking ball.

Photography is a way to bear witness to what Gore Vidal called “the United States Of Amnesia”, a way to document lost opportunities and wasted potential across the fifty states. Miles of once-vital roads that no longer lead anywhere: blocks of neighborhoods that now howl and whistle in a dead wind: acres of buildings that once housed history instead of cockroaches and cobwebs. All is ripe for either revelation or regret at the point of a camera.

Columbus, Ohio’s original air terminal building, opened in 1929 with hoopla and help from both Amelia Earhart and co-founder Charles Lindbergh, is one such location. Created as part of the country’s first fledgling attempt at a transcontinental air service (and this, only two years after Lindbergh’s astonishing solo flight to Paris) “Port Columbus” was solid proof that the air age was real.

Real enough, in fact, that a mere nineteen years later, the city’s air traffic had grown so rapidly that construction began on a shiny new international hub, big enough to accommodate a mid-century tourist boom, the jet era, and an explosion of international travel. The 1929 terminal was shuttered, living a few latter-day half-lives as offices for one short-term tenant or another, finally coming its silent rest on the Port’s back property, its legacy given half-hearted lip service with the obligatory plaque on the door.

Full disclosure: Columbus, Ohio was, for most of my life, my hometown. It is, among other things, a city of many firsts, a vital test market of ideas for everything from ATMs to hula hoops. And while I know that new uses won’t be in the cards for all historically important buildings there (or, indeed, anywhere), I am glad, at least, that, as photographers, we are privileged to say of such places: look here. This happened. This was important.

It’s often said that there are no second acts in American lives.

That’s tragic. And confounding.

(ALMOST) NO ADMITTANCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

DOORS PRESENT A MOST INTRIGUING PARADOX for the photographer. They are both invitations and barriers, the threshhold of opportunity and the end of it. Entrances and exits create a two-way traffic, with people either vanishing into or emerging from mystery either behind or in front of them. In either case, there are questions to be answered. And while the camera is certainly no x-ray, it does set the terms of the discussion…an endless discussion… about secrets.

Think of those fateful doors beyond which we know something portentous or crucial occurs. Ten Downing Street. The portal to an execution chamber. A confessional. An organization open to “Members Only”. Doors are like red meat to the photographer because they mean everything and nothing at once. Like the children of Pandora, we inherit the insatiable curiosity to know what’s back of that thing. Who’s there? Who’s not there? What does the great Oz look like? What’s going on inside that doesn’t invite me, doesn’t want me?

All barriers seem wrong, even cruel to us, on some level. “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall, that wants it down” writes Robert Frost in the poem Mending-Wall, and it seems like a reasonable sentiment. I can’t walk past a door, forbidding or friendly, without wanting my camera to go back and ask, knock, knock, who’s there? As an example the above image came to me unbidden, on a night in which my wife and I had walked along Queens Boulevard in New York in search of an all-night diner. Having succeeded in securing sustenance, we were walking home when a brief glimpse of a rather substantial iron gate became visible down a side street during the few scant moments it took us to skip through an intersection. I knew two things at once: I would never know what lay beyond that grand facade, and I would, still, have to make time to come back, on another night, to have my camera ask “the question.”

Photography can be about The Big Reveal, and often traffics in the solving of puzzles. But just picturing the puzzle is all right too. We don’t have to know whether the lady or the tiger is behind that door. We just have to use our magic boxes to knock on it.

BINGE / PURGE

I AM STILL IN PAIN, several days after the most aggressive photographic housecleaning I’ve endured in years, the ruthless removal of years of deadwood from a photo-sharing site on which I’ve parked way, way too many wayward pictures. This was, finally, the week to toss away the old moose head in the attic, the day to tearfully admit that you no longer fit into your varsity jersey. Hail and farewell, parting is such sweet sorrow. Goodbye and good riddance.

OVERHEARD DURING MY EDITING/DELETING PROCESS

Oh, My Gawd…

What even is that?

Well, that certainly didn’t work…..

Nothing wrong with this one…..except the lighting, aperture, and composition…

Seriously, what the hell is that?

Lots of this concentrated cringing over pix of yesteryear speaks to my old acronym SLAGIATT, or Seemed Like A Good Idea At The Time, the simple truth that what you believe is profound at the time of the shutter click will strike you as reeking fish wrap several miles down the pike. We do outgrow, update, and disown old ideas, hopefully replacing them with better ones.

To take it a bit further, if a significant number of your old images don’t make you want to reach for the bilge bucket, one of two things is true. (1) You are already God’s messenger, the one true Messiah of photography (unlikely), or (2) you are so mired in habit and false comfort that the way you shoot is the way you always shot and the way you will always shoot. Given those choices, it may be preferable to regard at least some of one’s work the way Jack Nicholson’s Joker riffed through Vicki Vale’s portfolio, i.e, “crap…..crap….crap…” It hurts, but it’s healthy.

Every binge must have a purge, and the gluttonous output of the digital age guarantees one sure truth: they can’t all be gems. I hate having to disown my kids as much as the next shooter, but part of learning is learning to fail, admitting that at least some of those kids will never Get Into A Good School, Settle Down With Someone Nice, and Start Giving Us Some Grandchildren. If for no other reason than to help us know excellence when we see it, we need to be able to fearlessly label all the loves we have lost.

ALONE OR LONELY?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NO TWO ARTISTS view the human condition of solitude in quite the same way. In photography, there are scores of shades between alone and lonely, between the peace of private reflection and the terror of banishment, shades which define their images as everything from comforting to terrifying. Thoreau hangs out solo in the woods and finds fulfillment. Hansel and Gretel, stranded in the forest, feel only dread.

The argument might be made that modern society at large fears solitude, that there is nothing more horrific than being alone left with one’s self. And, if that is your viewpoint, then that will eventually be reflected in how you depict people in isolation. Conversely, if you see “being apart” as an opportunity for self-discovery, then your photographs will show that, as well. You can’t “sit out” commenting on a fundamental part of the human condition. Some part of your own outlook will be stamped onto your photography.

That’s not to say that you can’t shade your “alone” work with layers of mystery, even some playfulness. Is the young woman shown here glad to be away from the crowd, or does she feel banished? Is her physical attitude one of relaxation or despair? The photographer need not spell everything out in bold strokes, and can even conspire to trick or confound the viewer as to his true feelings.

To make things even trickier, images can also convey the feeling of being alone in a crowd, lonely in a crushing multitude. That’s when the pictures get really complicated. With any luck, that is.

SPEED OF LIFE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NEW YORK CITY HAS BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS: words like titanic, exciting, merciless, dizzying, dangerous, even magical spring to mind immediately. By comparison, fewer observers refer to the metropolis with words like peaceful, tranquil, or contemplative, and fewer still would ever label it slow. Manhattan may be lacking for modern subways, open space, or a cheap cup of coffee, but it’s never short on speed.

NYC runs on velocity the way other towns run on electricity: the entire metro is one big panicky White Rabbit, glancing at his pocket watch and screeching “I’m late!” As a consequence, anyone making photographs in the Apple has to factor in all that velocity, or, more precisely, decide how (or whether) to depict it.

Do you try, for example, to arrest the city’s rhythm in flight, freezing crucial moments as if trapping a fly in amber, or, as in the image above, do you actively engage the speed, creating the sensation of New York’s irresistible forward surge as a visual effect?

Fortunately, there is more than a century of archival evidence that both approaches have their own specific power. Pictures made in the precise instant before something occurs are rife with potential. Images that show things in the process of happening convey a sense of excitement and immediacy. Like the lanes in a foot race, speed has discrete channels that can reward varying photographic approaches.

SPHERE ITSELF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CULTURAL ICONS, which burn very distinct patterns into our memory, can become the single most challenging subjects for photography. As templates for our key experiences, icons seem to insist upon being visualized in very narrow ways–the “official” or post card view, the version every shooter tries to emulate or mimic. By contrast, photography is all about rejecting the standard or the static. There must be, we insist, another way to try and see this thing beyond the obvious.

Upon its debut as the central symbol for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the stainless steel structure known as the Unisphere was presented as the emblem of the peaceful ideals put forth by the Exhibition’s creators. Under the theme “Peace Through Understanding”, the Uni, 120 feet across and 140 feet in height, was cordoned off from foot traffic and encircled by jetting fountains,which were designed to camouflage the globe’s immense pedestal, creating the illusion that this ideal planet was, in effect, floating in space. Anchoring the Fair site at its center, the Unisphere became the big show’s default souvenir trademark, immortalized in hundreds of licensed products, dozens of press releases and gazillions of candid photographs. The message was clear: To visually “do” the fair, you had to snap the sphere.

After the curtain was rung down on the event and Flushing Meadows-Corona Park began a slow, sad slide toward decay, the Unisphere, coated with grime and buckling under the twin tyrannies of weather and time, nearly became the world’s most famous chunk of scrap metal. By 1995, however, the tide had turned; the globe was protected by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and its rehabilitation was accompanied by a restoration of its encircling fountains, which were put back in service in 2010. The fair park, itself staging a comeback, welcomed back its space-age jewel.

As for photography: over the decades, 99% of the amateur images of the Unisphere have conformed to the photographic norm for icons: a certain aloof distance, a careful respect. Many pictures show the sphere alone, not even framed by the park trees that flank it on all sides, while many others are composed so that not one of the many daily visitors to the park can be seen, robbing this giant of the impact imparted by a true sense of scale.

In shooting Uni myself for the first time, I found it impossible not only to include the people around it, but to marvel at how completely they now possess it. The decorum of the ’64 fair as Prestigious Event now long gone, the sphere has been claimed for the very masses for whom it was built: as recreation site, as family gathering place..and, yes, as the biggest wading pool in New York.

This repurposing, for me, freed the Unisphere from the gilded cage of iconography and allowed me to see it as something completely new, no longer an abstraction of the people’s hopes, but as a real measure of their daily lives. Photographs are about where you go and also where you hope to go. And sometimes the only thing your eye has to phere is sphere itself.

TWO WORLDS, ONE WALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS BEGAN AS A SIMPLE HEAD–ON ENGAGEMENT. The viewpoint of the camera was essentially that of an audience member viewing a stage play, or reading a page of text, with all visual information reading from left to right. People stood in front of the lens in one flat plane, giving the appearance, as they posed before offices or stores, that they themselves were components in a two-dimensional painting. Everyone stared straight ahead as if in military formation or a class portrait, producing fairly stiff results.

We started photography by placing people in front of walls, then learned, like good stage managers, that selectively positioning or moving those walls could help image-makers manage the techniques of conceal/reveal. Now you see it, now you don’t. Photography no longer takes place in one plane: barriers shift to show this, or to hide that. They are part of the system of composition. Control of viewing angle does this most efficiently, as in the above image, where just standing in the right place lets me view both the front and back activities of the restaurant at the same time.

Of course, generations after the rigid formality of photography’s first framing so, we do this unconsciously. Adjusting where walls occur to help amplify our pictures’ narratives just seems instinctive. However, it can be helpful to pull back from these automatic processes from time to time, to understand why we use them, the better to keep honing our ability to direct the viewer’s eye and control the story.

THAT WHICH IS EARNED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE MORE INDEPENDENCE DAYS that I mark as an American, the more the holiday is fine-tuned, for me, from one of pure celebration to one of sober reflection. As a child, I waved my little flag, oohed and ahhed at fireworks, and ran up the scores of all our national wins and points of pride. As a middle-aged man, I think of the USA as a wonderful, but incomplete “to-do” list. I cherish what we’ve been but also try to be mindful of what we need to be. And that, in turn, widens my concept of what an Independence Day photograph can look like.

The above image, taken within the solemn sanctum of the 9/11 memorial, may not be many people’s choice for a “Happy 4th” -type picture, for a whole bunch of reasons. And I get that. There’s nothing celebratory about it. No wins, no rousing anthems. No amber waves of grain. That doesn’t mean, however, that it’s inappropriate. It may not rhapsodize about victory, but it does affirm survival. It doesn’t brag about what we have, but it does remind us of how much we stand to lose, if we take it easy, or take our eye off the ball.

The 9/11 site is unique in all the world in that it is battlefield, burial ground, transportation hub, commercial center, and museum all in one, a nexus of conflicting agendas, motives and memories. And while it’s a lot more enjoyable smiling at a snapshot of a kid with a sparkler than making pictures of the most severe tests of our national resilience, photography taken at the locations of our greatest trials are a celebration of sorts. Such pictures demonstrate that it’s the freedom we earn, as well as the freedom we inherit, that’s worth raising a cheer about.

And worth capturing inside a camera.

MR. KITE HAS LEFT THE BUILDING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY’S PRINCIPLE BENEFIT IS THE STEALING AND PRESERVATION OF THE FLEETING. That was the miracle that originally astonished the world, the ability to arrest time, to selectively snatch away droplets of the infinitely flowing river of moments and keep them in a jar. And as the young art flourished and began to flex, it proved capable of not only grabbing individual instants, but chronicling the passing of entire modes of life.

As the prairie was settled, as the great distances of the planet were traversed and tamed, as the horse gave way to the car, and as the country mouse became the city mouse, photography laid down mile markers, clearly labeled “this is”, “this is going away” and “this was”. As a consequence, we now have a visual record of worlds and ways of living that have already long since gone extinct. We rifle through shared and inherited images that mark the passing of empires, fashions, movements.

This is all, of course, beyond obvious, but there are times when photographers are more keenly mindful that something big is in the process of winking out. I experienced such a moment a few days ago with the news that Ringling Brothers’ circus was shuttering its operations after more than 150 years, ringing down the curtain on a mixed record of extravaganza and exploitation, depending on where you stand on the issue. Whether circuses were a wonder or an abomination or both, they represented a distinctly analog kind of entertainment, a direct tie between sensations and senses that is one of the last traces of 19th-century culture.

Along with world’s fairs, carnivals, vaudeville, even rodeo, the circus serves as a strange relic of a time when the arrival of the Wells Fargo wagon or the pitching of the Chautauqua tent could be the height of the social season in many a town. The visually rich pageant of having dozens of clowns, acrobats, and performing beasts parade right down your main street was, in the days before mass media, pretty heady stuff, and, even at its twilight, it still has a powerful, if quaint, pull on the imagination. All of this is fertile ground for the photographer/chronicler.

It’s now fifty years since John Lennon transcribed the text from an old circus poster to evoke a vanished era with the song Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite, overdubbing the music track with a montage of calliopes and hurdy-gurdys to paint a very visual piece of audio. To this day, I can’t hear the tune without concocting my own mental photo of prancing ponies and carnival barkers. Mr. Kite may already be retiring to his dressing room, as are so many analog forms of entertainment. But we have the pictures. Or we need to start making them.

EYES ON THE PRIZE FOR THE EYES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE INTERNET SCREECHED ITSELF HOARSE in 2016 when the Nobel Prize committee announced its intention to award one of its coveted awards for Literature to Bob Dylan, the first popular songwriter so honored. There were acrimonious screeds on both sides of the issue, as hands were wrung and garments were rent over whether Mr. D. was a poet or just a scribbler of post-beat pap. My initial reactions ranged from “really?” to, well, “really???“. But then I figured that, far from stretching the idea of “literature” too far, the Nobel gang hadn’t taken it far enough.

That is to say, it’s way past time for photographers to be invited onto the Nobel podium. As creators of visual literature.

Founded as an attempt by Alfred Nobel to expiate his guilt for having invented dynamite, the awards were designed to reward those whose work enriched or enlivened the human condition in the areas of chemistry, economics, physics, physiology/medicine, peace, and, yes, literature. As compared to the Pulitzer prize, which confers news value on both the printed word and photographic images, and is awarded for a singular piece of work within a single year, the Nobels are awarded for a body of work. With that standard in mind, it would actually be easier to judge the value of a photographer over a lifetime, versus the potential for a lucky or instinctual snap to be taken in the recording of a brief moment. But photography is a visual art, and a young one at that, and, even though no one still argues against its importance or impact, it is a sticky wicket to compel the powers that be to confer the “L-word” upon it.

Considering that the slight jump from literary poetry (Seamus Haney) to commercial song lyrics (Dylan) nearly caused Nobel critics to hemorrhage, proposing that photographs could also meet the definition of literature must sound, to some, like reciting dirty limericks during High Mass. Further, word “originalists” will point to the fact that literature is strictly defined as a written work of permanence. And yet it’s the permanence part that matters. Pictures have, in fact, changed arguments, minds and history, just as paintings have. And, if literature is that art which endures, something which defines the human experience, then a photograph is certainly as big an influence upon culture as a play or novel. A document is a document.

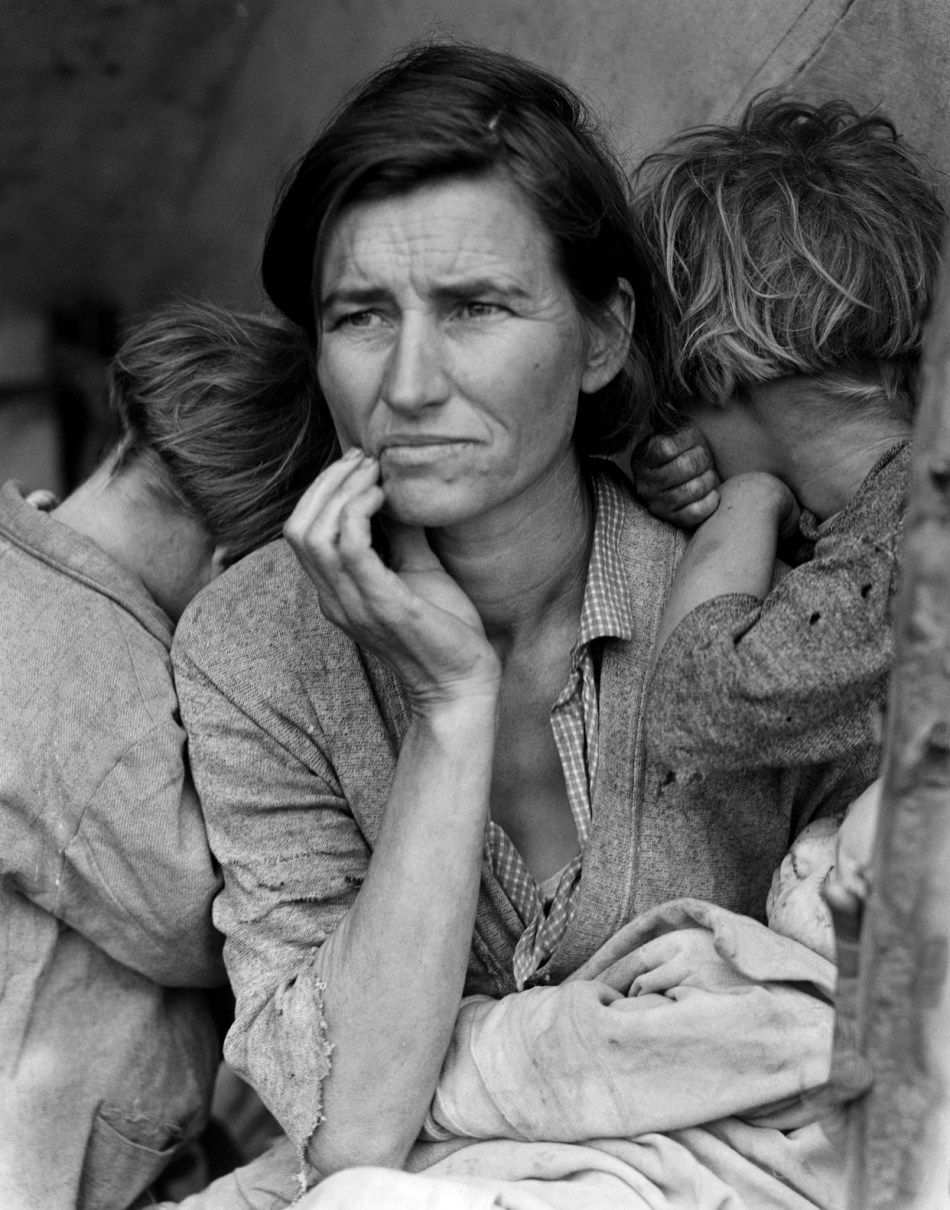

In accepting his Nobel prize, author John Steinbeck declared, “the writer is delegated to declare and celebrate man’s proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit..for gallantry in defeat…for courage, compassion, and love.” Now go from the general to the specific, considering Steinbeck’s amazing chronicle of the Oakie odyssey of the 1930’s, The Grapes Of Wrath. As a contrast, how does Dorathea Lange’s picture Migrant Mother, with its graphic depiction of the dust bowl era’s desperation and despair, have any less impact than Steinbeck’s glowing account of the Joad family’s trek to California? In my estimation, both works magnify and certify what it means to stand tall in the blowing gale of ill fortune. And that is a literary idea.

Migrant Mother, like Grapes, is no mere “one-off”, but a small part of an enormous oeuvre, a vast portfolio filled with eloquent testimonies that delineate humanity. The Nobel has slowly begun to mature with the awarding of Bob Dylan’s literature award. Now it’s time to regard the visual arts as part of that larger, and widening discussion.

STREETER THAN THOU

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF MY FAVORITE JOKES ABOUT HOW HUMANS END TO OVER-THINK THINGS involves a farmer standing by the side of the road with a herd of cattle, who is greeted by a passing urban tourist. “Excuse me”, says the visitor, “are those Herefords or Guernseys?” “Gee”, replies the farmer, “I just call ’em ‘moo-cows’!”

Similarily, I sometimes think that the weighted term street photography is more distinction than difference. City, country, street, pasture…hey, it’s all just pictures, right? Yes, I know….”street” is supposed to denote some kind of commentary, an interpretive statement on the state of humanity, an analysis on How We Got Here. Social sciences stuff. Street work is by nature a kind of preachment, born as it was out of journalism and artists like Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, who used images to chronicle the city’s ills and point toward solutions. For these geniuses and so many that followed, those street scenes rested fundamentally on people.

And by people, we mean discernible faces, unposed portraits that seared our souls and pricked our consciences. Street photography came to focus almost solely on the stories within those faces: their joy, their agony, their buoyant or busted dreams. In my own work, however, I am also drawn to street scenes where people are not front and center, but blended into the overall mix of elements, props, if you like, in an overall composition, like streetlamps, cars or buildings. There can be strong commentary in images that don’t “star” people but rather “feature” them. Walker Evans, one of the premiere shooters working for the New Deal’s Farm Security Administration, and creator of many classic depictions of the Great Depression, remarked that folks, as such, were not his aim when it came to street shots. “I’m not interested in people in the portrait sense, in the individual sense”, he said in 1971. “I’m interested in people as part of the pictures….as themselves, but anonymous.”

There is always a strong strain of competition among photographers, and street photography can become a wrestling match about who is telling the most truth, drilling down to the greatest revelation….a kind of “streeter than thou” mentality. However, just because something is raw and real doesn’t make it interesting, or else we could all just shoot the inside of garbage cans all day and be done with it. Compelling is compelling and boring is boring and if you know how to make a picture that grabs the eye better than the next guy, then subject matter, even motivation, doesn’t matter a damn. The picture is all. The picture will always be all. Everything else is noise.

RICH, TALENTED BOY MAKES GOOD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE MOST APPEALING FEATURE OF EVERY NEW ART is that, for a while, everyone participating in it is an amateur. Because a new art has no history, it has no history-makers….no professionals, no celebrated artistes, no one who is doing it better. Everyone is, briefly, in the same “how-do-you-work-this-thing?” boat.

Of course, eventually, some ornery cuss or another begins to figure out how to progress from stumblebum to star, and then everyone’s off to the races. Photography, like other infant arts, began as a tinkerer’s toy, sprouting an occasional outlier genius here and there, until the pool was fairly crowded with People Trying To Make Their Mark. And one of those first mark-makers was not yet out of short pants when his pictures began to be the embodiment of the phrase “and a little child shall lead them.”

His name was Jacques Henri Lartigue, and, whatever else formed his strong visual sense, it certainly wasn’t the nobility of poverty, born, as he was, in 1894 in France to upper-class wealth and the privilege that went with it. His photographic muse thus contained none of those inspiring Lean, Hungry Years or Hard-won Real World Experiences that we associate with mature art; the kid was just born with an instinctually strong knack for composition, and what he chose to compose just happened to be the activities of the Rich and Famous….in other words, everyone he hung out with.

Lartigue’s social set was the class every other social set in France aspired to; the people who seasoned at the Rive Gauche, the people who competed in lawn tennis tournaments, the country’s first race car drivers and aviators. Armed with a simple gift camera, and taught processing by his father, Jacques began snapping the world around him at age seven, maintaining journals that contextualized the images, bookmarking his family’s gilded role in the newborn twentieth century.

Gifted with an eye for photographic narrative, Lartigue nevertheless segued into painting, where he spent virtually his entire adult life. In fact, it was not until a friend showed some of Jacques’ photos to John Szarkowski, director of photography at the New York Museum of Modern Art, that Lartigue had his first formal photographic exhibition, in 1963, when he was sixty-nine.The show led to international recognition of his untutored yet undeniable talent, as well as a few prize portrait commissions and a second social career with the same elite one-percenters with whom he had rubbed elbows as a boy. One of his final collections, Diary Of A Century, was published in cooperation with Richard Avedon in 1978. He died a late-blooming “overnight success” at ninety-two.

What began for Jacques Henri Lartigue as family snapshots became one of the most important chronicles of a vanished world, and thus the best kind of photojournalism (or sociology, depending on your college major). For shooters, this boy of privilege remains the romantic ideal of the talented amateur.

THE YIELD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE ABILITY OF EVERY PHOTOGRAPHER, EVERYWHERE, TO INSTANTLY SHARE any part of his or her output with the world is both a blessing and curse. The “blessing” part’s easy to understand. Breaking down the barriers to publication of ideas that have separated us all from each other throughout time…well, that’s a very heady thing. Pictures can now transmit commentary at nearly the speed of thought, establishing linkages and narratives that have the potential to shape history.

Then there’s the “curse” part, in which this very same technology carries with it the potential for unlimited treachery and mischief. Who says what pictures can be seen…when, and by whom? Without supervisory curation or any kind of global uber-editor, photography can just be a visual torrent of garbage, or banality, or worse. Obviously, we have had to navigate some very tricky waters as both the blessing and curse elements of modern photography wrestle for supremacy.

What has happened for, good or ill, is that we are all, suddenly, tasked with being our own editors, asked to perform a skill that is very difficult to bring off with any honesty. You’d think that, after years of taking thousands of pictures, most of us would have a higher yield of excellence from all that work, but I have found that, at least for myself, the opposite is proving true. The more I shoot, the fewer of all those shots strike me as extraordinary. I thought that practice would indeed make perfect, or that, at least, I’d come closer to the mark more often, the more images I cranked off. But that hasn’t happened.

What has happened for, good or ill, is that we are all, suddenly, tasked with being our own editors, asked to perform a skill that is very difficult to bring off with any honesty. You’d think that, after years of taking thousands of pictures, most of us would have a higher yield of excellence from all that work, but I have found that, at least for myself, the opposite is proving true. The more I shoot, the fewer of all those shots strike me as extraordinary. I thought that practice would indeed make perfect, or that, at least, I’d come closer to the mark more often, the more images I cranked off. But that hasn’t happened.

Your skills accelerate over time, certainly; but so do your standards. In fact, any really honest self-editing journey will mean you are less and less satisfied with the same pictures, today, that, just yesterday, you would have thought your best work. You start to refuse to cut certain marginal pictures a break; you stop grading yourself on the curve.

Most importantly, you have been doing this just long enough to realize how very long the journey to mastery will be. Not just control of the mechanics of a camera, although that certainly takes time. No, we’re talking about learning to tame the wild horse of one’s own undisciplined vision, something that, over a lifetime, is hardly begun. Our moon landings come to look to us like baby steps.

Becoming one’s own editor means that, through the years, you’re liable to view one of your “greatest hits” from yesteryear and be able, sadly, to see the huge gulf between what you were trying to do and what you actually accomplished. I was horrified, a few years ago, to learn that my father, at some point, had destroyed the paintings he had made when he was in college. I had grown up with those images and thought them powerful, but he only saw their shortcomings, and, at some time or other, it was just too much to bear. I often think of those paintings now, whenever I view an older picture that I once thought of as “my truth”. In some cases, I can’t see anything in them but the attempt. A few of them do survive the years with something genuine to say…but, ask me again tomorrow, and I may reluctantly transfer many of them over to the “nice try” pile. It’s an imperfect process, but it’s only one I trust.

SPLIT DECISION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SEEMS TO BE A BIAS IN WHAT WE CALL STREET PHOTOGRAPHY that leans toward monochrome images, as if black and white were somehow more emotionally honest, maybe even more reportorially accurate as regards social commentary. I suppose this preference borrows a bit from the fact that journalism and photographic critique sort of grew up alongside each other, with black-and-white news coverage pre-dating the popular use of color by several decades. However, since color has become the primary, rather than the secondary choice for most photographers over the past forty or so years, there may be no leader or “winner” between bright and subdued hues, no real rule of thumb over what’s more “real.” Street, and the tones used to convey it, are in the eyes of the beholder.

There must be dozens of images that I myself take in color each year, that, upon later reflection, I re-imagine in mono. Of course, with digital imaging, it’s not only possible but probably smart to make one’s “master shots” in color, since modern editing programs can render more in the way of black and white than mere desaturation. Just sucking the color out of a shot is no guarantee that it will be more direct in its impact, and may actually drain it of a certain energy. Other times, taking out color can streamline the “reading” of a photograph, removing the distraction that can occur with a full range of tones. The only set answer is that there is no set answer.

In the film era, if you loaded black & white, you shot black & white. There was no in-camera re-think of the process, and few monochrome shots were artificially tinted after the fact. Conversely, if you loaded color, you shot color, and conversion to mono was only possible if you, yourself were expert in lab processing or knew someone who was. By contrast, in the digital age, there are a dozen different ways to reconfigure from one tone choice to another in seconds, offering the chance for anyone to produce almost limitless variations on an image while the subject is there is front of them, ripe for re-takes or re-thinks.

None of these new processes solve the ultimate problem of what tonal system works best for a given picture, or when you exercise that choice. However, the present age does place more decision-making power than ever before in the hands of the average photographer. And that makes street photography a dynamic, ever-changing state of mind, not merely an automatic bow to black-and-white tradition.

INVITATION TO THE DANCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY REACTS TO SHIFTS IN HUMAN BEHAVIOR, in that it both reports and creates the news. Let people surge or sparkle in any particular direction, and the camera will shift with them, for good or ill. Photographers are camp-followers by nature, and instinctively sniff out the Next Big Thing, the Next Medium Thing, even the next Is This A Thing? in search of subject matter.

There is, at this writing, a wealth of story-telling to be done in the rebirth of American urban centers, and it’s more than just stopping by the hottest new part of town. Suddenly, it’s about the complete reversal of the systemic desertion of cities that began right after World War II, with a new generation sizing up thousands of Spielbergian burbs and finding them wanting. Moreover, urban cores are being not just renovated but embraced, not merely as this year’s megatrend but as this age’s new answer. In city after city, we are coming home, transforming our idea of “a life” to define walkable neighborhoods, an explosion in the arts, dense diversity, and locally owned businesses. It’s a great time for cities, and a great time to be a photographer.

All of human activity, from ritual to celebration, social interaction to creativity, is being re-cast in urban terms, with block after block being claimed in the name of re-use and re-purpose. It’s greener, it’s groovier, and it is rich with visuals, as the barn dance becomes the street stomp and the dead warehouse becomes the very alive coffee-house. Most importantly, children are being born into places where they can walk to real shops versus driving to unreal chains. Something is up, and it’s not merely generational, and the camera has a role in all of this.

A role and a say.

THE WORKER’S SIGNATURE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GERMAN PHOTOGRAPHER AUGUST SANDER (1876-1964) created one of the most amazing projects in the history of portraiture with his seminal book The Face of Our Time. Born into a world that defined people much more by class division and by the literal work of their hands, Sander created a document of a vanishing world in a very simple way, surrounding bricklayers, cooks, soldiers, and dozens of other professionals with the literal tools of their trades. His work influenced street photography and portraiture throughout the 20th century, acting as both document and commentary.

The manual trades that Sanders celebrated are rapidly vanishing as automation and changing tastes take away the tv repairmen, cobblers, and pillow makers of yesteryear, taking with them the physical look of their workplaces. It’s feels like I’ve happened upon an archaeological dig when I run across a place where handcrafted work takes place, and to photograph the shops where the old magic still happens. The encroachment into urban neighborhoods of chain stores and the crush of ever-higher rents are chasing out the last generations of tinkerers and makers. Storefronts and the stories that reside within them are winking out across the urban landscape.

August Sander’s challenge to present-day photographers is to bear witness to the worker’s signature, the mark he makes on the world and the echo he leaves behind when he departs. The world is always in the act of going partly instinct. The camera measures what we lose in the process. In Sander’s elegant, simple pictures of working people, there is a peaceful quality, as everyone seems fitted to their place and role in the world. As we photograph the final days of such a world, we are commenting on the uncertainty that follows it into our present age.

A QUESTION OF BALANCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WITH PAINTING AS ITS INITIAL INFLUENCE, THE YOUNG ART OF PHOTOGRAPHY spent its first years trying to record transcendent scenes of the world, from landscapes to portraits, in much the same elegant, poetic way that such subjects were translated to the canvas. Partly due to the limits of early exposure media, the task of making a picture was slower in those first years, almost a contemplative act. And so, in pace and mood, the strange new machine seemed intent on imitating its painterly elder, at least in part to make the argument that even a machine could be imbued with an artist’s eye.

Then came faster film and faster events. The images of war and the advancing grind of city life coincided with the introduction of more responsive films. The snapshot, the ability to catch an accelerating world on the fly, became commonplace. Photography took on a new role as reporter’s tool, a way to visually testify to human problems and their impacts. Photojournalism, in turn, gave way to commerce, which created an image bias in news coverage that persists to the present day. Photos take their tone from the needs of the marketplace. Tragedy outsells beauty. If it bleeds, it leads. Pulitzer prizes aren’t awarded to people who make pictures of daffodils.

And yet, there is a greater need for pictorial beauty than ever before, simply so that our visual diet doesn’t consist solely of red meat and blood. Certainly, the sensational holds tremendous sway over what gets published, re-printed, re-tweeted. The images that stamp themselves on our brains hold many traumas and dramas. Admittedly, some have sparked outrage, which in turn spurs action, and that can be a good thing. But photography can make us hard and jaded as well, and we dare not squeeze beauty into the margins of our consumption. Pictures shape feelings, and they can also condition us to feel less and less about more and more.

From Lewis Hine’s harrowing pictures of children in cotton mills to present-day iPhone dispatches from the latest repressions or riots, photographs are the seismograph of our collective consciences. But just as man cannot live on bread alone, he cannot subsist solely on nightmares. Beauty, harmony, aspiration, hope….we need to capture all these as well, lest, under the barrage of the shell and the bullet, the butterfly is blasted into extinction.

It’s a question of balance.

SUNSETTING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN RAY BRADBURY’S WONDERFUL ONE-ACT PLAY, TO THE CHICAGO ABYSS, an old man equipped with a near-photographic memory makes both friends and enemies because he remembers so much of a world vanished in the aftermath of global war. His talent lies not merely in being able to conjure the world of large things….cathedrals, cars, countries, but of the micro-minutia of a life, a realm filled with the colors of cigarette packages, what compressed air sounded like hissing out of a newly opened can of coffee, the names of candy bars. The play reminds us that it is the million little pieces, the uncountable props of daily living, that matter…..especially when they are no more.

Professions and services offer the photographer the chance to preserve entire miniature worlds for the viewer, worlds which are in the constant process of sunsetting, of transitioning from “is” to “was”. Shops where we used to get our watches repaired. Bookstores that are now furniture warehouses. Home where those people we knew, oh, you know their names, used to live. Was it on the corner? Or over there?

Even when long-familiar things survive in some form, they are not quite as we knew them. Does anyone still get their shoes re-soled? Was there ever a time when “salons” were just “barber shops”? Was it, long ago, some kind of luxury to weigh yourself for a penny in the bus station? Photos of these daily rituals take on even greater import as time re-contexualizes our lives, shuffling our position in the cosmic deck. Decades hence, we almost need visible evidence that we ever lived this way, ever dressed like that.

I love shooting businesses that should not be around, but are, places that should have already been scrubbed from day-to-day experience, but stubbornly linger around the edges. Images taken of these places argue strongly that not all forward motion is progress, that the familiar and the comfortable are also little pieces of our identity. In the words of the old song, there used to be ballpark right here.

Here, I have a picture of it…..

UNKNOWN KNOWNS

Everyone is visible, yet no one is known. Faceless crowds serve as shapes and props in a composition.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WE OFTEN WRITE IN THESE PAGES ABOUT PHOTOGRAPHY’S UNIQUE ABILITY to either reveal or conceal, and how we toggle between these two approaches, given the task at hand. Photographic images were originally recorded by using science to harness light, to increase its ability to illuminate life’s enveloping darkness, just as Edison did with the incandescent bulb. And in their attempt to master a completely new artistic medium, early photographers were constantly pushing that dark/light barrier, devising faster films and flash technology to show detail in the darkest, dimmest corners of life.

And when that battle was won, an amazing thing happened.

Photographers realized that completely escaping the dark also meant running away from mystery, from the subtlety of suggestion, from the unanswered questions residing within their pictures’ shadows. And from the earliest days of the 20th century, they began to selectively take away visual information, just as painters always had, teasing the imagination with what could not be seen.

City scenes which feature individual faces in crowds opt for the drama (or boredom) written in the face of the everyday man. Their scowls at the noonday rush. Their worry at the train station. Their motives. But for an urban photographer, sometimes using shadow to swallow up facial details means being free to arrange people as objects, revealing no more about their inner dreams and drives than any other prop in an overall composition. This can be fun to play with, as some of the most unknowable people can reside in images taken in bright, public spaces. We see them, but we can’t know them.

Experimenting with the show it/hide it balance between people and their surroundings takes our photography beyond mere documentation, which is the first part of the journey from taking pictures to making them. Once we move from simple recording into interpretation, all the chains are off, and our images can really begin to breathe.

O SILVER TREE, O SILVER TREE……

Cussins & Fern Hardware, Columbus, Ohio, Christmas 1965

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CBS TELEVISION FIRST AIRED A Charlie Brown Christmas on December 9, 1965, creating an instant seasonal classic. It got its first tenuous viewing despite the network suits’ fears that the modest little story, voiced by children(!), sporting a jazz soundtrack(!) and gently suggesting that the holiday may be about more than greed and glitz, would lay a giant Yuletide egg. They needn’t have worried, as it turned out. The show nobody wanted became the tradition without which no Christmas could be thought to be complete.

One of the show’s main plot points involves Charlie Brown’s fear that the holiday has been hijacked by hucksters, so much so that the hottest selling Christmas trees in his neighborhood are not verdant firs but pastel-painted, neon monstrosities. There was a lot of that nonsense going on in those days.

The photograph you see here was taken just days after that first airing of ACBC, but I can’t really claim to be channeling its energy or trying to echo its sentiments. The picture isn’t so much a comment on commercialism (nothing that formal) so much as it is a question.

I was a very young thirteen in December 1965, and had only wielded my Imperial Mark XII box camera on a few occasions prior to the day I found myself wandering around Northern Lights shopping center in Columbus, Ohio, specifically past the display window of the Cussins & Fern Hardware Company. Like Charlie Brown, I thought that some holiday novelties, like the recently introduced aluminum Xmas trees were odd, even though I liked the included rotating wheels that projected ever-changing colors onto the silvery sticks in a kind of robotically cold imitation of gaiety. However, unlike Charlie Brown, I don’t think I regarded these abstract Future Trees as an affront to decency. I just thought they were weird.

I do remember thinking that the window showed a Christmas that was just kind of……off, a Christmas in which you got a whole television set or a food freezer as a present, a Christmas filled with Strange Trees From The Future, a Christmas where you could always buy….money orders? I knew, in that era, next to nothing about how to formally frame a shot or a visual commentary. I didn’t have the pictorial vocabulary to make an argument. I couldn’t interpret. I just pointed at things that interested me and trusted those things to carry their own narrative weight. I was point-and-shoot before point-and-shoot wuz cool.

This Christmas, both the holiday and I are still in flux. I continue to point my camera at shop windows, and continue to wonder what the whole mad mix of beauty and banality means. I still don’t have the answer. Alas, as a photographer, you often have to be content with merely learning better ways to ask the question.

Now, if I can just find someplace to buy Uncle Ed that money order he asked for…..

Share this:

December 22, 2017 | Categories: Americana, Christmas, Commentary | Tags: Holiday photography, Techniques and Styles | Leave a comment