BECAUSE WEIRD ISN’T FOREVER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHAT DO YOU DO when you’re a quirky bit of modern art and the museum that hosts you has been shuttered for missing the rent? Futher, let’s assume your creator’s homeland regards your “art” as political blasphemy and let’s also stipulate that you are, say, a fifteen-foot-high chromed head of Vladimir Lenin with a tiny baby balanced on its top.

In the words of Randy Newman, “I Love L.A.”

Beginning in 2011, expatriot Chinese artist brothers Gao Zhen and Gao Qiang found a home for their satirical sculpture, Miss Mao Trying To Poise Herself At The Top Of Lenin’s Head, in front of Los Angeles’ ACE Museum at 4th Street and La Brea Avenue. Locals and tourists alike soon embraced the weird, much as motorists might grow fond of sites like The Giant Ball Of String or The World’s Crookedest House, worshiping the sheer asinine novelty of the thing over any aesthetic merit. The result? Art meant as provocation landed, instead, with the soft cushiony comfort of fun, an ironic landmark, as in, “to get to my house, take the first left after the Lenin head..”

But here’s the take-away for photographers. Part of our job is to freeze the human drama as it shifts and morphs. That means being particularly sensitive to the things in society that change the quickest, including the fashion waves of the art world. And if serious art falls out of favor quickly, art that is loaded with satire or irony really races to the front of the obsolescence checkout. Weird ain’t forever.

Lenin and Miss Mao found by 2017 that it’s hard to stay a head (sorry) when the ACE Museum was evicted, leaving the work essentially homeless. Zhen and Qiang tried in vain to land the Commie Chromedome a new roost in China, but the Big Red One basically told them to pound sushi (humorless bunch, those socialists). What’s a murderous goateed revolutionary to do?

Well.

At this writing (June 2018), the most recent citing of Vlad’s Big Head was at the site of a trucking company near Newberry Springs, California, in the Mojave Desert, property owned by artist Weiming Chen, a friend of the Gao brothers who operates the area as a kind of statuary boneyard for his own works and those of others. A snapshot taken of the head showed Lenin looking characteristically defiant, although absent the lovely Miss Mao. I like to think she’s found peace as the hood ornament for a 1966 Diamond Reo rig highballing down CA-10. Hey, I can dream.

So, I treasure my 2014 snap of the head in situ in L.A. (seen above), back when life was good and fate was kind. Photography is commentary, but often, the top comment that comes to mind is something like “okaaaaay, so that happened..” No matter: it’s always worth a grin, and usually worth a picture.

As with Miss Mao, it’s a balancing act.

WE NEVER CLOSE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE DEMIMONDE. The night shift. The third trick. Up with the dawn. Done for the night.

At any given time, some of us are starting our days and heading to work while others are wrapping up their labors and stumbling into bed. Our nights are others’ days, our bustle others’ quiet time. We come at life on the planet from different directions, our suns and moons meeting at the time clock. Wait till coffee break, say some. That’s when things really get going. Hang around till after midnight, say the rest. That’s when this place really start to happen.

Time really comes unmoored in the cities, where our deliveries, destinies and dreams are on all kinds of stop/start cycles. The big town is as photographically alive for the night owls as for the morning glories. People whose days are other people’s nights are forever exotic and strange to each other, the images of their routines as mutually mysterious as the extremes of heat and cold. And always, the same underlying drum beat: got things to do. No day or night, pal: things get done when they get done.

The camera never sleeps because we never close. Open seven days a week, open all night. Last train at midnight, early bird special, full price after six, in by 9, out by 5. Rules of engagement for the breakfast surge, the lunch rush, the dinner crowd. Lives in motion. Pistons rising and falling. Disharmony and sweet accord.

The shutters keep blinking. The moments keep rolling.

24/7.

ONE MOTIVE AT A TIME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CROWDS ARE OFTEN DESCRIBED as if they were single entities, as if each member were acting in accord with all others, like cells combining to form an organ. Writers likewise use the word “crowd” as a kind of collective noun, as in “the crowd went wild” or ” the crowd grew restless”, again making it seem as if a collection of individuals can act as a single thing. Spend time in any crowd as a photographic observer, however, and it becomes obvious that there is virtually no such thing as group behavior. Everyone comes to a crowd separately, one motive, one agenda at a time, and photographers can begin to harvest real human stories by seeing them that way.

To be sure, there is scope and drama in making uber-pictures that convey the sheer size and scope of mass gatherings. Likewise, there are certainly moments when crowds seem to be moving or acting as one, as in the moment when the winning run is hit or a rousing orator evokes a roar of approval. But look carefully within those general waves of action and you will still see the individual proudly on display. By turns, he is, even in a crowd, engaged, irritated, enthusiastic, bored, tired, ecstatic, and angry, just as visibly as if he were in any other situation. Get close enough to a mass of people and you’ll see The Person…..perhaps attempting to be part of something larger than himself, but still pushing his own brand of street theatre, still brandishing his own quirks.

Demonstrations, parades, celebrations, protests….they’re all staging points for persons, persons who give up their stories to the photographer’s eye no less in a mob than in the family den. Wait for the moment when that happens and grab it. Teach yourself to look at a crowd and see the person who’s truly one in a million.

PHASES AND STAGES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MORE INK HAS BEEN POURED OUT about Henri Cartier-Bresson’s notion of “the decisive moment” than perhaps any other chunk of photographic philosophy ever hashed out between honest brokers. HCB’s assertion was, essentially, that there is a single, ideal instant in which a picture of something will be, like an apple, perfect for the plucking. Miss that moment, and all is lost.

While some applaud this theory as holy scripture, others dismiss it with a vulgar reference to bovine by-products. All well and good. Everyone needs to evolve a belief system that drives their personal photographic vision. The important thing is to evolve something.

Personally, while I don’t believe there is only a single moment that will make an image immortal, I also don’t think that just any moment you choose to freeze an event is as good as every other moment. Conditions, timing and decisions matter in the making of a picture, and, when they intersect, the magic happens.

So the number of “decisive moments” for an event, for me, would number about three. Think of them as acts in a play, each act performing a distinct element in a dramatic story. Act One shows things that are about to happen: a nearly blooming blossom: the minutes before street lights are turned on for the evening. Act Two depicts something that is in the process of occurring: candles on a cake being blown out: a pistol shot. And Act Three shows where things have now completed. A concert crowd leaves the theatre: a dog snoozes after a long day of play.

The image seen here can potentially be an example of any of the three acts. Are the backstage props being spread out in anticipation of a show? Is the performance, unseen from this angle, being given right now? Or have the stage hands already begun to strike the tents and gather everything up before moving the players on to the next town? All three interpretations are of specific places in time. And all can be “decisive moments” when the right bond between photographer and viewer is established.

A SUPERIOR DAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LIKE MANY TOWNS in the American southwest, Superior, Arizona sprung up in the nineteenth century primarily to get people close to something promising that Nature had already parked in the local dirt. So long as that something gushed up, flashed in a prospector’s pan or helped light or heat something, the towns flourished….. boomed, as the term goes.

Until they didn’t.

In the case of Superior (2010 census population 2,837), the silver that anchored the locals to the grim crags of the Superstitions mountain range tumbled in value when the metal lost its status as the backing for the American dollar in 1893. Fortunately, Superior had a second act, rebounding with the discovery of copper in the same area where silver had been mined. And then, of course, Hollywood came calling, seeking a visual taste of the Real Old West. Superior rose yet again, standing in for yesteryear in the films How The West Was Won, Blind Justice, and The Gauntlet, among many others. And the beat goes on; as recently as the 1990’s, yet another copper mining company hooked Superior up to yet one more source of life support. And how’s your hometown?

Even so, a photographer looking to take Superior’s pulse in the twenty-teens is well advised to look a little deeper than the shopworn storefronts of the main street, heavy with thrift shops and antique stores but also alive with hot pastels and the twang of Saturday afternoon dance music, complete with Stetsons and cold longnecks. The town is rusty and dusty down to its toenails, pressed up against gritty stone peaks, but it is still brave at the corners of its mouth. As a place that is “a fur piece” from Phoenix and a hoot and a holler from Globe, Superior is more mile marker than actual destination, but it is still standing, still smiling for the camera.

And, who knows, things could change.

They always have before….

THE COWGIRL IN THE BLEACHERS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM NEVER TRULY COMFORTABLE working with a camera that isn’t physically locked onto my eye. Shooting without a viewfinder was, for me, perhaps the hardest part of gradually embracing cel photography, and continues to be a control issue that still inclines me toward my Nikons most of the time. Part of it, I freely admit, is mere sentimental habit……maybe even, who knows, superstition?…..and yet when I’m crammed up against that little square of glass, I feel as if I’m “really” taking a picture.

That’s why it’s really a rare bird for me to “shoot from the hip” with a DSLR, to try to sneak a street candid without my camera anywhere near my face at all, holding the thing at mid-chest or waist level or even squeezing off a frame while it’s hanging from my shoulder. If the opportunity is literally too juicy to resist, and if looking like a (gasp) photographer will spook my quarry (or get a Coke thrown in my face), well, then, desperate times call for desperate measures.

I arrived at such a “desperate times” moment the other day by being caught out with the wrong lens. I had thought that I would be spending my afternoon at a horse show inside barns and stables, indicating a wide-angle to open up cramped spaces, so I packed a 24mm to go wide but keep distortion to a minimum. Once Marian and I arrived at the event, however, she got interested in an arena competition, and so in we went. Now I’m taking big shots of a cavernous hall punctuated by long lines of little tiny horses. If a rider lopes directly in front of my seat, I can almost make out his face. Otherwise I’m zoomless and story-less. Can we go home now?

I hear a husky female drawl off to the left.

“Jus’ let her walk, Annie. She wants to walk.”

Turns out the voice belongs to a spangled matron with a Texas twang sharp enough to chop cheddar, herself apparently just off the competition track and now shouting guidelines to another woman in the field. I immediately fall in love with this woman, hypnotized by her steely stare, her no-nonsense focus, and the fact that, unlike the far-away formations of horses directly in front of me, she is a story. A story I need to capture.

But any visible sign of guy-with-a-camera will ruin it all. I will swing into the range of her peripheral vision. Her concentration will break. Worse, the change in her face will make the story all about the intrusive jerk six feet away. And so I hug the camera to the middle of my chest, the lens turned generally in her direction. Of course I have no reliable way to compose the shot, so I spend the next several minutes shooting high, low, losing her completely in the frame, checking results after every click, and finally settling on the image you see here, which, despite my “calculations” for a level horizon, looks a bit like a shot from the old Batman tv series. Holy carsickness.

Strangely, shooting at actual horses (at least with the glass I brung) was telling me nothing about horse culture. But the lady with the spangly blouse and Stetson got me there. It’s literally her beat, and I was grateful to, yes, sneak a glimpse at it.

LEADING FROM THE REAR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHING CROWDS IS SOMEWHAT AKIN to using one’s camera to track a billowing cloud of soap suds. The shape of the mass shifts constantly, roiling this way and that, presenting the shooter with an ever-evolving range of choices. Is this the shape that delivers the story? Or does this arrangement of shapes do it?

And is just the size of the overall crowd the main visual message….with the perfect picture merely showing a giant jumble of bodies? Plenty of great images have been made that convey a narrative with just mass or scale. But throngs are also collections of individuals. Can’t a compelling tale also be told focusing on the particular?

When shooting any large gathering, be it a festival, a party or a demonstration, I am torn between the spectacle of the “cast of thousands” type shot and the tinier stories to be had at the personal level. In the shot seen below, I was following a parade, actually behind the traditional approach to such an event. What arrested my attention from this vantage point was the printed shawl of the woman directly ahead of me. The graphic on the shawl had been seen on other flags and banners in the march, but, billowing in the breeze on her back, the print became a kind of uniform for the march… a theme, a face all its own.

In this context, I didn’t need to see the actual expressions of the marchers: there was enough information in their body language, especially if I composed to place the woman at the center of the shot, as if she were the leader. That was enough. The actual march boasted thousands, but I didn’t need to show them all. The essence of everyone’s intentions could be shown by the assemblage of small parts.

Some crowd photographs speak loudly by showing the sheer volume of participants on hand. Others show us the special energies of individuals. Neither approach is universally sufficient, and you’ll have to see which is better for the narrative you’re trying to relate in a particular moment.

NOMADS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN A PARTICULARLY CHILLING SCENE from the classic film The Third Man, Orson Welles, as the story’s amoral profiteer Harry Lime, looks down from a carnival ride to the teeming, tiny throngs on the pavement below, distancing himself from people that have been reduced, in his mind, to mere ‘dots’. ” Tell me”, he asks his friend Holly Martens, “would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving forever?” Lime has, in fact, been selling tainted medicine to desperate refugees in post-war Berlin, and his product does, almost certainly, make several of those dots stop moving. Forever. Horrible, and yet his estrangement from his fellow wanderers on that sidewalk occurs all the time in all our minds. When we look more carefully, more compassionately, however, photographs can happen.

We are all nomads, wanderers, dots on a map. We convince ourselves that our journey is surely taking us toward something….a very important something. As for everyone else….what? Like Harry Lime, we place great emphasis on our own story, with ourselves cast as the hero. In fact, though, pulling one’s eye just far enough back from the throng can show our camera’s eye the real story. Every journey, every destination is equal….equally vital or equally banal. It’s the process of observing that seeking that creates a tableau, a composition. That, and how we view it.

I take a lot of images of crowds in motion: streaming in and out of buildings, rushing for trains, teeming through malls, crowding the subway. What they’re after isn’t what gives them the drama. It’s the continuous process of seeking, of going toward all our collective somewheres, that provides the narrative. I don’t try to record faces: these are moving chess boards, not portraits. Additional clinical distance can come from the use of monochrome, or angle of view. Sometimes I think of the overhead camera shots of director Busby Berkeley, he of the kaleidoscopic dance routines in 42nd Street and other ’30’s musicals. The rush of the crowd is all a kind of choreography, intentional and random at the same time.

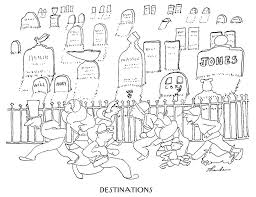

One of the images that brought this idea home to me as a child was a cartoon James Thurber drew for the New Yorker titled “Destinations”(above left). It shows, simply, a rightward mob rushing toward a leftward mob, with a cemetery in the background. Everyone is headed for the same end point but all act as if they are bound for someplace else. The story for a photographer in all this wandering lies in how we look as we do it. Where we eventually wind up may well be fate’s whim, but the story of all the comings and the goings, of ourselves and our fellow nomads, is in the hands of the camera.

ON THE JOB

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST EXHAUSTIVE portrait projects in the history of photography was August Sander’s Face Of Our Time, a collection from the 1920’s of sixty formal portraits of German tradesmen of every class and social station, each shown with the tools or uniforms unique to his chosen profession. Sanders photographed his subjects as documents, without any hint of commentary or irony. The story in their pictures was, simply, the visual record of their place in society and, eventually, as cultural bookmarks.

Since Sander’s eloquent, if clinical work, similar photo essays have taken on the same subject with a little more warmth, notably Irving Penn’s Small Trades portrait series from the early 1950’s. Like Sander, however, Penn also shot his images in the controlled environment of the studio. In my own work, I truly feel that it’s important to capture ordinary workers in their native working environment, framed by everything that defines a typical day for them, not merely a few symbolic tools, such as a bricklayer’s trowel or a butcher’s cleaver. I also think such portraits should be unposed candids, with the photographer posing as little distraction as possible.

I really like the formal look of a studio portrait, but it doesn’t lend itself to reportage, as it’s really an artificial construct….a version of reality. So called “worker” portraits need room to breathe, to be un-self-conscious. And, at least for me, that means getting them back on the street.

ON DISPLAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ALTHOUGH MUSEUMS ARE DESIGNED as repositories of history’s greatest stories, I often find that the most compelling narratives within those elegant walls, for the photographer in me, are provided by the visitors rather than the exhibits.

We’ve seen this effect at zoos: sometimes the guy outside the ape house bears a closer resemblance to a gorilla then the occupant within. With the museum experience, making controlled, serene exposures of the artifacts is never as interesting as turning your reporter’s eye on the folks who came in the door. The juxtaposition of all the museum’s starched, arbitrary order with humanity’s marvelously random energy creates a beautifully strange staging site for social interaction….great hunting for street shooters.

The sculpture gallery shown here, one of the most beautiful rooms in Manhattan’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, is certainly “picturesque”enough all by itself. However when the room is used to frame the chessboard-like weaving of live humans into the pattern of sculpted figures, it can create its own unique visual choreography, including the mother who would love to bottle-bribe her baby long enough to finish just one more chapter.

Anyone who’s visited The Normal Eye over the years recognizes this museum-as-social-laboratory angle is a consistent theme for me. I just love to mash-up big art boxes with the people who visit them. Sometimes all you get is statues. Other times, one kind of “exhibit” feeds off the other, and magic happens.

LOW INFO AND HIGH NARRATIVE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU DON’T HAVE TO KNOW all the elements of a story to tell it visually. Yes, photography certainly has the technical means to tell a detailed tale, but that narrative need not be spelled out in every particular by the camera.

Indeed, it might be the very information that’s “missing” that may be the most compelling element of a visual story. That is to say, if you don’t know all the facts, make the picture. And if you do have all the facts, maybe leave out a few…. and make the picture anyway.

The above image illustrates this strange mis-match between storytelling and story material. As a shooter, I’m tantalizingly close to the couple at the table next door to me at a plaza restaurant. I mean, I can practically count the salt grains on the lady’s salad. I can also tell, by her male companion’s hand gestures, that a lively conversation is underway. But that is the sum total of what I know. I can’t characterize the discussion. A business planner? A lover’s quarrel? Closing the sale? Sharing some gossip? Completely unknown. Sure, I could strain to pick up a word here or there, but that alone may not be enough to provide any additional context, and, in fact, I don’t need that information to make a picture.

This is what I call “low info, high narrative”, because I don’t require all the facts of this scene to sell the message of the picture, which is conversation. As a matter of fact, my having to leave out part of the image’s backstory might actually broaden the appeal of the final product, since the viewer is now partnering with me to provide his/her version of what that story might be. It’s like my suggesting the face of a witch. By merely using words like ugly or horrible, I’ve placed you in charge of the “look” of the witch. You’ve provided a vital part of the picture.

You won’t always have the luxury of knowing everything about what you’re photographing. And, thankfully, it doesn’t really matter a damn. That’s why we call this process making a picture. We aren’t merely passive recorders, but active, interpretive storytellers. High narrative beats low info every time.

ONE GLIMPSE OF WAS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE EXQUISITE PLEASURES usually denied to even the best portrait photographers is the ability to turn back the clock, to use the camera to x-ray one’s way past a subject’s accumulated life layers, peering into the “them” that was. It’s not really that it’s impossible to retrieve part of a person’s yester-faces. It’s that it’s maddingly elusive, like getting a brief glimpse of a lighthouse beacon amidst billows of pea-soup fog. We have to take faces, for the most part, at, well, face value.

Case in point: meeting my wife, as I did, long after we both had lived fairly complete first lives, I can only know the early visual version of her through other people’s pictures. It allows me to look for parts of those earlier faces whenever I make new images of her, but I can never know when any of them will flash up to the surface. It does happen, but there’s no way to summon it at will.

Marian grew up in a beach town, with the seasons and rhythms of shore life defining her own to a degree. As a consequence, I always welcome the chance to shoot her near the sea….along beaches, atop windswept piers, weaving her way through the sights and sounds of boardwalks and harbors.

Of course, restoring Marian to her original context, by itself, is no guarantee that I’ll harvest any greater photographic truth about her face’s formative years than I do on any other day. Still, I find the idea romantic and brimming with tantalizing potential. Will I be given an audience with the ghosts of Marian past today? Will they even show up? The mystery of faces leads photographers on a blind chase, with only the occasional find to convince us to continue the hunt.

SPEED OF LIFE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NEW YORK CITY HAS BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS: words like titanic, exciting, merciless, dizzying, dangerous, even magical spring to mind immediately. By comparison, fewer observers refer to the metropolis with words like peaceful, tranquil, or contemplative, and fewer still would ever label it slow. Manhattan may be lacking for modern subways, open space, or a cheap cup of coffee, but it’s never short on speed.

NYC runs on velocity the way other towns run on electricity: the entire metro is one big panicky White Rabbit, glancing at his pocket watch and screeching “I’m late!” As a consequence, anyone making photographs in the Apple has to factor in all that velocity, or, more precisely, decide how (or whether) to depict it.

Do you try, for example, to arrest the city’s rhythm in flight, freezing crucial moments as if trapping a fly in amber, or, as in the image above, do you actively engage the speed, creating the sensation of New York’s irresistible forward surge as a visual effect?

Fortunately, there is more than a century of archival evidence that both approaches have their own specific power. Pictures made in the precise instant before something occurs are rife with potential. Images that show things in the process of happening convey a sense of excitement and immediacy. Like the lanes in a foot race, speed has discrete channels that can reward varying photographic approaches.

RE-ASSIGNING VALUE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY DEMONSTRATED, EARLY IN ITS HISTORY, that, despite the assumption that it was merely a recording device, it regarded “reality” as….overrated. Since those dawning daguerreotype days, it has made every attempt possible to distort, lie about, or improve upon the actual world. There is no “real” in a photograph, only an arrangement between shooter and viewer, who, together, decide what the truth is.

So-called street photography is rife with what I call “reassigned value” when it comes to the depiction of people. Obviously, the heart of “street” is the raw observation of human stories as the photographer sees them, tight little tales of endeavor, adventure…even tragedy. However, the nature of the artist is not to merely document but also to interpret: he may use the camera to freeze the basic facts of a scene, but he will inevitably re-assign values to every part of it, from the players to the props. He becomes, in effect, a stage manager in the production of a small play.

In the above image you can see an example of this process. The man sitting at his assigned post at a museum gallery began as a simple visual record, but I obviously didn’t let the matter end there. Everything from the selective desaturation of color to the partial softening of focus is used to suggest more than what would be given in just a literal snap.

So what is the true nature of the man at the podium? Is he wistfully gazing out the distant window, or merely daydreaming? Is he regretful, or does he just suffer from sore feet? Is he chronically bored, or has his head in fact turned just because a patron asked him the direction of the restroom? And, most importantly, how can you creatively alter the perception of this (or any) scene merely by dealing the cards of technique in a slightly different shuffle?

Photographers traffic in the technical measure of the real, certainly. But they’re not chained to it. The bonds are only as steadfast as the limit of our imagination, or the terms of the dialogue we want with the world at large.

TWILIGHT TIME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE STRUGGLED OVER A LIFETIME to tell photographic stories with as few elements as possible. It’s not unlike confining your culinary craft to four-ingredient recipes, assuming you can actually generate something edible from such basic tools. The idea, after all, is whether they’ll eat what you’ve cooked.

With images, I’ve had to learn (and re-learn) just how easy it is to lard extra slop onto a picture, how effortlessly you can complicate it with surplus distractions, props, people, and general clutter. Streamlining the visual language of a picture takes a lot of practice. More masterpieces are cropped to perfection than conceived that way.

The super-salesman Bruce Barton once said that the most important things in life can be reduced to a single word: hope, love, heart, home, family, etc. And so it is with photographs: images gain narrative power when you learn to stop sending audiences scampering around inside the frame, chasing competing story lines. Some of my favorite pictures are not really stories at all, but single-topic expressions of feeling. You can merely relate a sensation to viewers, at which point they themselves will supply the story.

As an example, the above image supplies no storyline, nor was it meant to. The only reason for the photo is the golden light of a Seattle sunset threading its way through the darkening city streets, and I have decided that, for this particular picture, that’s enough. I have even darkened the frame to amp up the golds and minimize building detail, which can tend to “un-sell” the effect. And yet, as simple as this picture is, I’m pretty sure I could not have taken it (or perhaps might not even have attempted it) as a younger man. I hope I live long enough to teach myself the potential openness that can evolve in a picture if the shooter will Just. Stop. Talking.

THE GOLDEN HALF-RULE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE STREET-HARDENED CRIME PHOTOGRAPHER ARTHUR FELLIG (1899-1968), who adopted the pseudonym “Weegee” was often asked the secret of his success as the journalist who best captured the stark essence of mobster arrests, gruesome murders, and various other manifestations of mayhem and tragedy. He had answered the “how do you do it” question so many times that he developed a uniform shorthand response which passed into photographic lore and stamped itself onto the brains of all future street shooters. The secret: “f/8 and be there.”

The “f/8” part spoke to the fact that Weegee, who seldom shot at any other aperture, was more interested in bringing back a usable picture than in creating great art. In the days before autofocus, shots taken on the fly at medium distance would almost always be reasonably sharp at that depth of field, no matter how sloppy the shooter’s finer focusing technique. Besides, since he was capturing sensation, not romance, why bother with subtle nuance? Weegee’s pictures were harsh, brutal, and grimy, just like the nether worlds they depicted. They were known for their high contrast and for the atomic blast of hard flashgun light he blew into the faces of society mavens and thugs alike. We’re talking blunt force trauma.

Familiar with action on both ends of guns, Arthur “Weegee” Fellig was the ultimate chronicler of America’s dark side.

The second half of Weegee’s golden rule was far more telling for any photographer purporting to be an effective narrator. When Fellig spoke of “being there” he was not only referring to arriving on a crime scene ahead of any competition (which he guaranteed by grabbing early bulletins from the police-band radio in his car and having a mobile darkroom in his trunk), but in being mentally present enough to know when and what to shoot, with very little advance prep. The bulkiness of the old Graphlex and Speed Graphic press cameras (the size of small typewriters) meant that shooting twenty frames in as many seconds, as is now a given with reporters, was technically impossible. Time was precious, deadlines loomed, and knowing when the narrative peak of a story was approaching was an invaluable instinct, one which distinguished Weegee from his contemporaries. Opportunities were measured in seconds, and photogs learned to nail a shot with very little notice that history was about to be on the wing.

There will always be arguments about the finer points of focus and exposure, with most debates centering on the first half of Weegee’s prime directive. However, for my money, the urgency of being ably to identify immediacy and grab it in a box far outweighs the niceties of art. Many a Pulitzer Prize-winning image is under-exposed or blurs, while many a technically perfect picture actually manages to drain a scene of any human emotion. Make it f/8, f/4, hell, take the damned thing with a pinhole if need be. But be there.

EYEWITNESSED AND UNDERLINED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT WASN’T LONG AFTER THE INTRODUCTION OF PHOTOGRAPHY that one of the biggest and most durable myths about the new art was launched to generally unquestioning acceptance. The line “the camera doesn’t lie” attached itself to the popular imagination with what seemed the purest of industrial-age logic. Photographs were, to the 19th-century mind, a flawless record of reality, a scientifically reliable registration of light and shadow. And yet the only thing that moved as quickly as photography itself was the race to use the camera to deliberately create illusion, and, eventually, to serve the twin fibbing mills of propaganda and advertising. The camera, it turned out, not only could lie, but did do so, frequently and indetectably.

Later, as photojournalism came into its own, the “doesn’t lie” myth seemed to drape news coverage in some holy mantle of trustworthiness, as if every cameraman were somehow magically neutral in the way he shot an event. This, in spite of the obvious fact that, merely by changing composition, exposure, or processing, the photographer could alter his image’s impact…..its ability to, in effect, transmit “truth”. Certainly, outright fakery got better and better, but, even without deliberately trying to falsify facts, the news photographer still had his own personal eye, an eye which could easily add bias to a seemingly straightforward picture. Did this proclivity make his pictures “lies”?

As a point of discussion, consider the above photo, which is, fundamentally, a document of part of an actual event. But what can really be learned from what’s in the frame? Are there thousands at this rally, or do the attendees shown here constitute the entire turnout? Are all those on hand peaceful and calm, or have I merely turned my lens away from others, immediately adjacent, who may be screaming or gesturing in anger? And how about my use of selective focus with the girl in pink? Am I simply calling attention to her face, the colors in her outfit, her sign, her physical posture… or am I trying to make her argument for her by using blur to make everyone else seem less important? Am I an artist, a reporter, a liar, or all three?

Here’s the thing: since I don’t make my living as a journalist, I can choose any or all of those three job titles without fear of conflict. I work only for myself, so I make no claim for the neutrality of my coverage of anything, including landscapes, still lifes and portraits. I likewise make no guarantees of objectivity in what I regard as an art. Only the observer can decide whether the camera, or I, have “lied”. We repeat this mantra frequently, but it bears clear emphasis: photographs are not (mere) reality. Never were, never can be.

Good thing or bad? You literally take that determination into your own hands.

STREETER THAN THOU

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF MY FAVORITE JOKES ABOUT HOW HUMANS END TO OVER-THINK THINGS involves a farmer standing by the side of the road with a herd of cattle, who is greeted by a passing urban tourist. “Excuse me”, says the visitor, “are those Herefords or Guernseys?” “Gee”, replies the farmer, “I just call ’em ‘moo-cows’!”

Similarily, I sometimes think that the weighted term street photography is more distinction than difference. City, country, street, pasture…hey, it’s all just pictures, right? Yes, I know….”street” is supposed to denote some kind of commentary, an interpretive statement on the state of humanity, an analysis on How We Got Here. Social sciences stuff. Street work is by nature a kind of preachment, born as it was out of journalism and artists like Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, who used images to chronicle the city’s ills and point toward solutions. For these geniuses and so many that followed, those street scenes rested fundamentally on people.

And by people, we mean discernible faces, unposed portraits that seared our souls and pricked our consciences. Street photography came to focus almost solely on the stories within those faces: their joy, their agony, their buoyant or busted dreams. In my own work, however, I am also drawn to street scenes where people are not front and center, but blended into the overall mix of elements, props, if you like, in an overall composition, like streetlamps, cars or buildings. There can be strong commentary in images that don’t “star” people but rather “feature” them. Walker Evans, one of the premiere shooters working for the New Deal’s Farm Security Administration, and creator of many classic depictions of the Great Depression, remarked that folks, as such, were not his aim when it came to street shots. “I’m not interested in people in the portrait sense, in the individual sense”, he said in 1971. “I’m interested in people as part of the pictures….as themselves, but anonymous.”

There is always a strong strain of competition among photographers, and street photography can become a wrestling match about who is telling the most truth, drilling down to the greatest revelation….a kind of “streeter than thou” mentality. However, just because something is raw and real doesn’t make it interesting, or else we could all just shoot the inside of garbage cans all day and be done with it. Compelling is compelling and boring is boring and if you know how to make a picture that grabs the eye better than the next guy, then subject matter, even motivation, doesn’t matter a damn. The picture is all. The picture will always be all. Everything else is noise.

SPLIT DECISION

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SEEMS TO BE A BIAS IN WHAT WE CALL STREET PHOTOGRAPHY that leans toward monochrome images, as if black and white were somehow more emotionally honest, maybe even more reportorially accurate as regards social commentary. I suppose this preference borrows a bit from the fact that journalism and photographic critique sort of grew up alongside each other, with black-and-white news coverage pre-dating the popular use of color by several decades. However, since color has become the primary, rather than the secondary choice for most photographers over the past forty or so years, there may be no leader or “winner” between bright and subdued hues, no real rule of thumb over what’s more “real.” Street, and the tones used to convey it, are in the eyes of the beholder.

There must be dozens of images that I myself take in color each year, that, upon later reflection, I re-imagine in mono. Of course, with digital imaging, it’s not only possible but probably smart to make one’s “master shots” in color, since modern editing programs can render more in the way of black and white than mere desaturation. Just sucking the color out of a shot is no guarantee that it will be more direct in its impact, and may actually drain it of a certain energy. Other times, taking out color can streamline the “reading” of a photograph, removing the distraction that can occur with a full range of tones. The only set answer is that there is no set answer.

In the film era, if you loaded black & white, you shot black & white. There was no in-camera re-think of the process, and few monochrome shots were artificially tinted after the fact. Conversely, if you loaded color, you shot color, and conversion to mono was only possible if you, yourself were expert in lab processing or knew someone who was. By contrast, in the digital age, there are a dozen different ways to reconfigure from one tone choice to another in seconds, offering the chance for anyone to produce almost limitless variations on an image while the subject is there is front of them, ripe for re-takes or re-thinks.

None of these new processes solve the ultimate problem of what tonal system works best for a given picture, or when you exercise that choice. However, the present age does place more decision-making power than ever before in the hands of the average photographer. And that makes street photography a dynamic, ever-changing state of mind, not merely an automatic bow to black-and-white tradition.

HOW TERRIBLY STRANGE…..

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOME IMAGES REQUIRE NO WORDS. At least that’s the standard we aim for.

Many others may or may not benefit from what I call accompaniment. Sometimes a few words act as a sort of period at the end of a photographic “sentence”. Other times, a pre-existing sentiment….literary, musical, poetic…. seems somehow to have been just waiting for a picture with which to pair up.

I shot this picture of two longtime pals in just a second, but for two weeks after that, my mind kept looping back to 1968, and the words of a then-young songsmith who found it a real mind stretch to picture himself at the opposite end of his life. And, most likely, many other baby-boomers who read those lyrics, from the Simon & Garfunkel Bookends album of fifty years ago, tried to make the same mental leap. In 2018, those of us lucky enough to have made that journey to “the other side”, living out those dreams of dotage, may be, even now, able to recall that young writer’s words at will:

*****************

Old Friends / old friends / sat on their park bench like bookends

A newspaper blown through the grass falls on the round toes/ of the high shoes

Of the old friends

Old friends / winter companions, the old men

Lost in their overcoats / waiting for the sunset

The sounds of the city sifting through trees settle like dust on the shoulders

Of the old friends

Can you imagine us, years from today, sharing a park bench quietly?

How terribly strange to be seventy……

************

(c) 1968 Paul Simon

Here’s to songs that are worth a thousand pictures, and to pictures that try to return the favor….

Share this:

June 26, 2018 | Categories: Commentary, Conception | Tags: Music, Street Photography | Leave a comment