REVELATION OR RUT?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S OFTEN DIFFICULT FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS, UNDER THE SPELL OF A CONCEPT, TO KNOW WHETHER THEY ARE MARCHING TOWARD SOME LOFTY QUEST or merely walking in circles, their foot (or their brain) nailed to the floor. Fall too deeply in love with a given idea, and you could cling to it, for comfort or habit, long after it has yielded anything remotely creative.

You might be mistaking a rut for revelation.

We’ll all seen it happen. Hell, it’s happened to many of us. You begin to explore a particular story-telling technique. It shows some promise. And so you hang with it a little longer, then a little longer still. One more interpretation of the shot that made you smile. One more variation on the theme.

Maybe it’s abstract grid details on glass towers, taken in monochrome at an odd angle. Maybe it’s time exposures of light trails on a midnight highway. And maybe, as in my own case, it’s a lingering romance with dense, busy neighborhood textures, shot at a respectfully reportorial distance. Straight-on, left to right tapestries of doors, places of business, upstairs/downstairs tenant life, comings and goings. I love them, but I also worry about how long I can contribute something different to them as a means of telling a story.

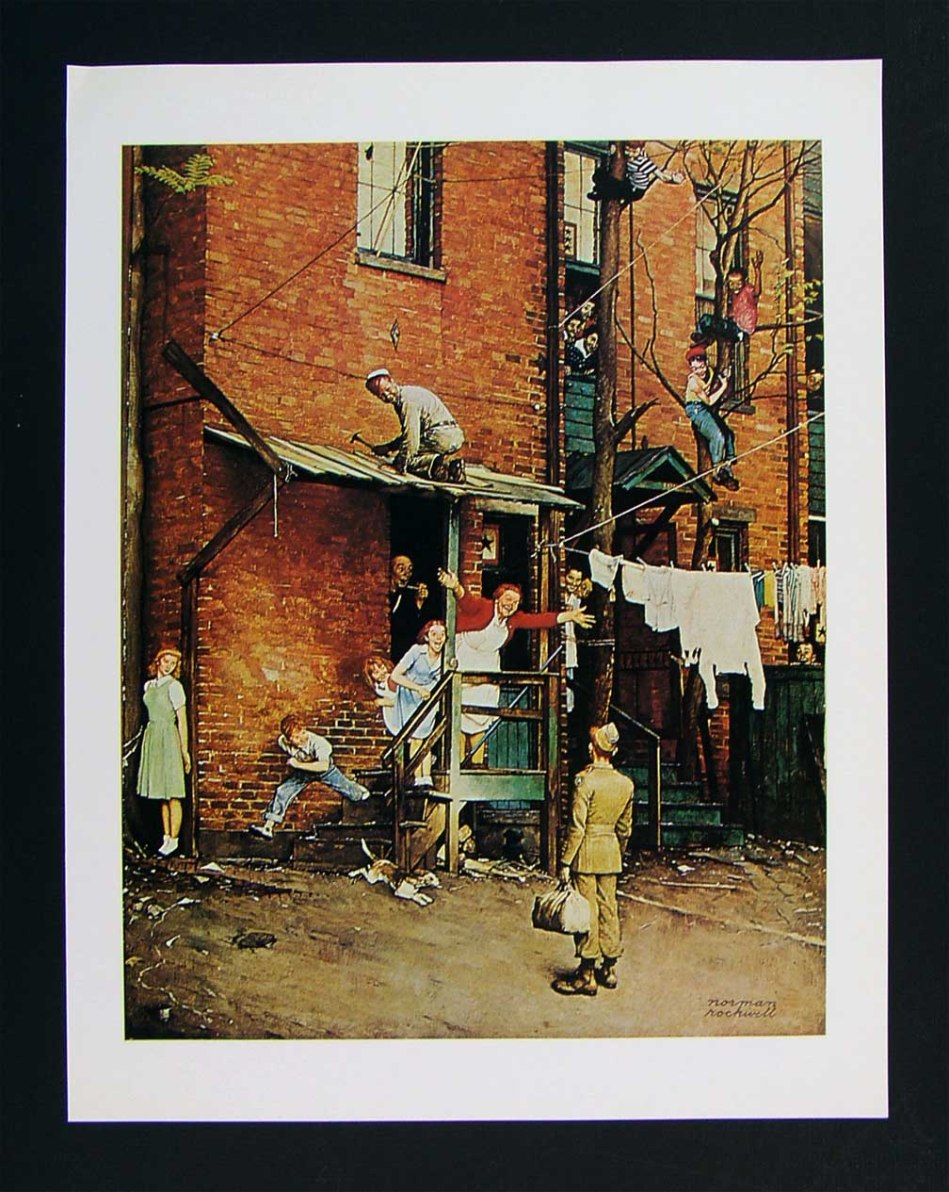

As staged as a Broadway show, Norman Rockwell’s idealized neighborhoods are still alluring in their appeal.

- The bustling tenement neighborhoods of early Norman Rockwell paintings appealed to me, as a child, because the frames were teeming with life: people leaning out of windows, sitting on porches, perching on fire escapes, delivering the morning milk…they were a divine, almost musical chaos. But they were paintings, with all the intentional orchestration of sentiment and nostalgia that comes with that medium. Those images were wonderful, but they were not documents…merely dreams.

That, of course, doesn’t make them any less powerful as an influence on photography.

When I look at a section of an urban block, I try to frame a section of it that tells, in miniature, the life that can be felt all day long as the area’s natural rhythm. There are re-gentrified restaurants, neglected second-floor apartments, new coats of paint on old brick, overgrown trees, stalwart standbys that have been part of the street for ages, young lovers and old duffers. Toss all the ingredients together and you might get an image salad that captures something close to “real”. And then there is the trial-and-error of how much to include, how busy or sparse to portray the subject.

That said, I have explored this theme many times over the years, and worry that I am trying to harvest crops from a fallow field. Have I stayed too long at this particular fair? Are there even any compelling stories left to tell in this approach, or have I just romanticized the idea of the whole thing beyond any artistic merit?

Hopefully, I will know when to strike this kind of image off my “to do” list, as I fear that repetition, even repetition of a valid concept, can lead to laziness….the place where you call “habit” a “style”.

And I don’t want to dwell in that place.

IT’S NOT EASY BEIN’ GREEN

This is the desert? A Phoenix area public park at midday. There is a way around the intense glare. 1/500 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm, straight out of the camera.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR YEARS I HAVE BEEN SHOOTING SUBJECTS IN THE URBAN AREAS OF PHOENIX, ARIZONA, trying to convey the twin truths that, yes, there are greenspaces here, and yes, it is possible for a full range of color to be captured, despite the paint-peeling, hard white light that overfills most of our days. Geez, wish I had been shooting here in the days of Kodachrome 25. Slow as that film was, the desert would have provided more than enough illumination to blow it out, given the wrong settings. Now if you folks is new around here, lemme tell you about the brilliant hues of the Valley of the Sun. Yessir, if’n you like beige, dun, brown, sepia or bone, we’ve got it in spades. Green is a little harder to come by, since the light registers it in a kind of sickly, sagebrush flavor….kind of like Crayola’s “green-yellow” (or is it “yellow-green”?) rather than a deep, verdant, top-o-the-mornin’ Galway green.

But you can do workar0unds.

In nearby Scottsdale, hardly renowned for its dazzling urban parks (as opposed to the resort properties, which are jewels), Indian School Park at Hayden and Indian School Roads is a very inviting oasis, built around a curvy, quiet little pond, dozens of mature shade trees that lean out over the water in a lazy fashion, and, on occasion, some decorator white herons. Thing is, it’s also as bright as a steel skillet by about 9am, and surrounded by two of the busiest traffic arteries in town. That means lots of cars in your line of sight for any standard framing. You can defeat that by turning 180 degrees and aiming your shots out over the middle of the pond, but then there is nothing really to look at, so you’re better off shooting along the water’s edge. Luckily, the park is below street level a bit, so if you frame slightly under the horizon line you can crop out the cars, but, with them, the upper third of the trees. Give and take.

There is still a ton of light coming down between the shade trees, however, so if you want any detail in the water or trees at all, you must shoot into shade where you can, and go for a much faster shutter speed….1/500 up to 1/1000 or faster. It’s either that or shoot the whole thing at a small f-stop like f/11 or more. In desert settings you’ve got so much light that you can truly dance near the edge of what would normally be underexposure, and all it will do is boost and deepen the colors that are there. There will still be a few hot spots on projecting roots and such where the light hits, but the beauty of digital is that you can click away and adjust as you go.

It’s not quite like creating greenspace out of nothing, but there are ways to make things plausibly seem to be a representation of real life, and, since this is an interpretive medium, there’s no right or wrong. And the darker-than-normal shadows in this kind of approach add a little warmth and mystery, so there’s that.

It was “yellow-green”, wasn’t it?

Hope that’s not on the final.

(follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye)

THE PROSCENIUM

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT IS THE OLDEST FRAMING DEVICE IN HISTORY. If you’ve ever watched a play on any stage, anywhere in the world, you’ve accepted it as the classic method of visual presentation. The Romans coined the word proscenium, “in front of the scenery”. Between stage left and stage right exists a separate reality, defined and contained in the finite space of the theatre’s forward area. What is included in the frame is everything, the center of the universe of certain characters and events. What’s outside the frame is, indefinite, vague, less real.

Just like photography, right? Or to be accurate, photography is like the proscenium. We, too select a specific world to display. We leave out all the other worlds not pertinent to our message. And we follow information in linear fashion…left to right, right to left. The frame gives us the sensation of “looking in” to something that we are only visiting, just as we only “rent” our viewpoint from our theatre seats.

We learned our linear habit from the descendants of stage arrangement….murals, frescoes, paintings, all working, as our first literate selves would, from left to right. Painters were forced to arrange information inside the frame, to make choices of what that frame would include, and, as the quasi-legitimate children of painting, we inherited that deliberately chosen viewpoint, that decision to show a select world, by arranging visual elements within the frame.

Park Slope, Brooklyn, 2012. Trying to catch as much activity as a street glance, at any given moment, can. 1/320 sec., F/7.1, ISO 100, 24mm.

For some reason, in recent months, I have been abandoning the non-traditional in shooting street scenes and harking back to the proscenium, trying to convey a contained world of simple, direct left-right information. Candid neighborhood shots seem to work well without extra adornment. Just pick your borders and make your capture. It’s a way of admitting that some worlds come complete just as they are. Just wrap the frame around them like a packing crate and serve ’em up.

Like a theatre play, some images read best as self-contained, left-to-right “worlds”. A firehouse in Brooklyn, 2012. 1/60 sec., f/6.3, ISO 100, 38mm.

This is not to say that an angled or isometric view can’t portray drama or reality as well as a “stagy” one. Hey, sometimes you want a racing bike and sometimes you want a beach cruiser. Sometimes I don’t mind that the technique for getting a shot is, itself, a little more noticeable. And sometimes I like to pretend that there really isn’t a camera.

That’s theatre. You shouldn’t believe that the well-meaning director of the local production of Oklahoma really conjured a corn field inside a theatre. But you kind of do.

Hey what does Picasso say? “Art is the lie that tells the truth”?

Okay, now I’m making my own head hurt. I’m gonna go lie down.

LOOK THROUGH ANY WINDOW, PART ONE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE COMMON THREAD ACROSS ALL THE PHOTO HOW-TO BOOKS EVER WRITTEN IS A WARNING: don’t let all the rules we are discussing here keep you from making a picture. Standardized techniques for exposure, composition, angle, and processing are road maps, not the Ten Commandments. It will become obvious pretty quickly to anyone who makes even a limited study of photography that some of the greatest pictures ever taken color outside the classical lines of “good picture making.” The war photo that captures the moment of death in a blur. The candid that cuts off half the subject’s face. The sunset with blown-out skies or lens flares. Many images outside the realm of “perfection” deliver something immediate and legitimate that goes beyond mere precision. Call it a fist to the gut.

The dawn creeps slowly in on the downtown streets of Monterey, California. A go-for-broke window shot taken under decidedly compromised conditions. 1/15 sec., f/3.5, ISO 640, 18mm.

Conversely, many technically pristine images are absolutely devoid of emotional impact, perfect executions that arrive at the finish line minus a soul. Finally, being happy with our results, despite how far they are from flawless is the animating spirit of art, and feeling. This all starts out with a boost of science, but it ain’t really science at all, is it? If it were, we could just send the camera out by itself, a heart-dead recording instrument like the Mars lander, and remove ourself from the equation entirely.

Thus the common entreaty in every instruction book: shoot it anyway. The only picture that is sure not to “come out” is the one you don’t shoot.

The image at left, of a business building in downtown Monterey, California was almost not taken. If I had been governed only by general how-to rules, I would have simply decided that it was impossible. Lots of reasons “not to”; shooting from a high hotel window at an angle that was nearly guaranteed to pick up a reflection, even taken in a dark room at pre-dawn; the need to be too close to the window to mount a tripod, therefore nixing the chance at a time exposure; and the likelihood that, for a hand-held shot, I would have to jack the camera’s ISO so high that some of the darker parts of the building would be the smudgy consistency of wet ashes.

Still, I couldn’t walk away from it. Mood, energy, atmosphere, something told me to just shoot it anyway.

I didn’t get “perfection”. That particular ideal had been yanked out of my reach, like Lucy pulling away Charlie Brown’s football. But I am glad I tried. (Click on the image to see a more detailed version of the result)

In the next post, a look at another window that threatened to hold a shot hostage, and a solution that rescued it.

Related articles

- 7 Ways to Inject More Creativity Into Your Photos (blogworld.com)

TRAVEL JITTERS

“Autumn in New York, why does it seem so inviting?” A shot inside Central Park, November 2011. 1/60 sec., f/5.6, ISO 160, 50mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF THERE IS SUCH A THING AS PHOTOGRAPHIC STAGE FRIGHT, it most likely is that vaguely apprehensive feeling that kicks in just before you connect with a potentially powerful subject. And when that subject is really Subject One, i.e., New York City, well, even a pro can be forgiven a few butterflies. They ain’t kidding when they sing, if I can make it there I can make it anywhere. But, of course, the Apple is anything but anywhere…….

Theoretically, if “there are eight million stories in the Naked City”, you’d think a photographer would be just fine selecting any one of them, since there is no one single way of representing the planet’s most diverse urban enclave. And there are over 150 years of amazing image-making to support the idea that every way of taking in this immense subject is fair territory.

And yet.

And yet we are drawn (at least I am) to at least weigh in on the most obvious elements of this broad canvas. The hot button attractions. The “to-do list” locations. No, it isn’t as if the world needs one more picture of Ellis Island or the Brooklyn Bridge, and it isn’t likely that I will be one of the lucky few who will manage to bring anything fresh to these icons of American experience. In fact, the odds are stacked horribly in the opposite direction. It is far safer to predict that every angle or framing I will try will be a precise clone of millions of other visualizations of almost exactly the same quality. Even so, with every new trip to NYC I have to wean myself away from trying to create the ultimate postcard,to focus upon one of the other 7,999,999 stories in the city. Even at this late date, there are stories in the nooks and crannies of the city that are largely undertold. They aren’t as seductive as the obvious choices, but they may afford greater rewards, in that there may be something there that I can claim, that I can personally mine from the rock.

By the time this post is published, I will be taking yet another run at this majestic city and anything additional in the way of stories that I can pry loose from her streets. Right now, staring at this computer, nothing has begun, and everything is possible. That is both exhilarating and terrifying. The way to banish the travel jitters is to get there, and get going. And yes, I will bring back my share of cliches, or attempts at escaping them. But, just like a stowaway on a ship arriving in the New World, something else may smuggle itself on board.

I have to visit my old girlfriend again, even if we wind up agreeing to be just friends.

And, as all photographers (and lovers) do, I hope it will lead to something more serious.

Thoughts?

PLAN B, C, D…..

San Francisco decides what to give you, weather-wise. You have decide to accept or reject it, picture-wise.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOME ICONIC SUBJECTS ACTUALLY SUBVERT CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHY, since they fire a normal human urge to record “your take” of an image that literally millions have taken before. There is a strong temptation to merely simulate or re-create the ideal depictions of such objects, be they skyscrapers or mountains, cathedrals or canyons. There is an inherent trap in this process, of course. Why strive to merely match what others have done, to ape or emulate the “ideal” shot? Why settle for the chance to render a Xerox of someone else’s vision?

However, just because I can recognize this trap doesn’t mean I haven’t fallen into it. Indeed, as recently as last week, I found myself despondent because I was being denied the “perfect” shot of San Francisco’s #1 visual trademark…the Golden Gate Bridge. I was visiting the marvelous new Walt Disney Family Museum, housed inside re-purposed buildings in the Presidio, whose severe, spartan brick buildings are an inspiring reminder of their original role as a line of national defense for this vital port. However, for me in 2012, they were attractive chiefly because they were the last layer of urban development before the bridge. I drooled over the images on the museum’s website. It’s right in their backyard! Moreover, the only place in the Disney museum where photography is allowed is along a glass walled gallery specifically designed to serve up the perfect shot of Big Red. Perfect, right?

Except that, on the day I visited the museum, a stubborn canopy of fog had refused to clear the bridge towers, even in the clear light of late afternoon sun. There goes plan A. I left the building convinced that I could shoehorn a telephoto shot in between Presidio buildings and still get my “optimum” shot. I soon realized, however, that plan B was also unworkable. The fog stubbornly persisted in eclipsing the top of the south tower, while the property fence in my immediate view was chopping into a clear shot of its foundations. What remained looked cluttered, wrong, unconventional. Then plan C came into focus. Shoot something. Try to save this. Can I make a composition out of these stark brick blocks of space, with a glimpse of the tower in between? I was on total instinct by this time. My wife was waiting in the car, we were both tired after a day of flying, and it was just a whole helluva lot easier to just walk away. Enter the rationale: The bridge isn’t going anywhere. There have to be a million places to stand and get the “right” shot I want. Run away and live to fight another day.

And yet.

There was just a twinkling of an idea….not really a fully formed concept, just a seed pod. The bridge is, given the local weather, always in the process of being concealed and revealed. Photographers have made great images of the bridge not only when it can be seen but when it coyly hides, like Salome, beneath the veils of weather. In fact, many of the best pictures of the bridge have been made under adverse conditions. Artistically, I was in good company. The bridge is always teasing, always taunting: come and find me. Try to define me. I dare you to capture me. I am not easy.

I am not obvious.

To hell with it.

I decided to wedge the partially visible tower between two dead blocks of brick, and make the picture. Like an immigrant who has to look through a dirty window to see a fast, smeared glimpse of Lady Liberty as he enters New York harbor, I knew I was stealing a view, snatching a fragment, a bit of hope, a shard of truth. I had to settle. I had moved plan C up to A position and was determined to live with the choice. Strangely, I will, upon future visits to San Francisco, feel a little cheap taking the “perfect” shot, if it ever presents itself.

I am no longer so certain of the best way to approach this subject. Whether I really got something or whether I am merely rationalizing my long shot in a lousy situation, I can no longer determine. But I am happy with what happened. And that’s supposed to be what this is all about.

Thoughts?

Related articles

- In The Presidio: Hard To Imagine, But There Wasn’t Always A Bridge Across The Golden Gate (sf.curbed.com)

- Plans Set, Drivers Brace For Golden Gate Bridge 75th Anniversary (sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com)

BIG STORY, LITTLE STORY

Which image better conveys the romantic era of the Queen Mary, the wide-angle shot along the promenade deck (above), or a detail of lights and fixtures within one of the ship’s shops (below)?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE VERY APPEAL THAT ATTRACTS HORDES OF VISITORS to travel destinations around the world, sites that are photographed endlessly by visitors and pilgrims alike, may be the same thing that ensures that most of the resulting images will be startlingly similar, if not numbingly average. After all, if we are all going for the same Kodak moment, few of us will find much new truth to either the left or right of a somewhat mediocre median.

In a general sense, yes, we all have “access” to the Statue of Liberty, the Grand Canyon, Niagara Falls, etc., but it is an access to which we are carefully channeled, herded, and roped by the keepers of these treasures. And if art is a constant search for a new view on a familiar subject, travel attractions provide a tightly guarded keyhole through which only a narrowly proscribed vantage point is visible. The very things we have preserved are in turn protected from us in a way that keeps us from telling our subject’s “big story”, to apprehend a total sense of the tower, temple, cathedral or forest we yearn to re-interpret.

More and more, a visit to a cultural keepsake means settling….for the rooms you’re allowed to see, the areas where the tours go, the parts of the building that have been restored. Beyond that, either be a photographer for National Geographic, or help yourself to a souvenir album in our gift shop, thank you for your interest. Artistically speaking, shooters have more latitude in capturing the stuff nobody cares about; if a locale is neglected or undiscovered, you have a shot at getting the shot. Imagine being Ansel Adams in the Yosemite of the 1920’s, tramping around at will, decades before the installation of comfort stations and guard rails, where his imagination was only limited by where his legs could carry him (and his enormous and unwieldy view camera, I know). Sadly, once a site has been “saved”, or more precisely, monetized, the views, the access, the original feel of its “big story” is buried in theme cafes, commemorative shrines, info counters, and, not insignificantly, competition with every other ambitious shooter, who, like you, wants a crack at whatever essences can still be seen between the trinkets and kiosks.

On a recent visit to the 1930’s luxury liner RMS Queen Mary, in Long Beach, California, I tried with mixed results to get a true sense of scale for this Art Deco leviathan, but its current use as a hotel, tour trek and retail mall has so altered the overall visual flow that in some cases only “small stories” can effectively be told. Steamlined details and period motifs can render a kind of feel for what the QM might have been before its life as a kind of ossified merchandise museum, but, whereas time has not been able to rob the ship’s beauty, commerce certainly nibbles around its edges.

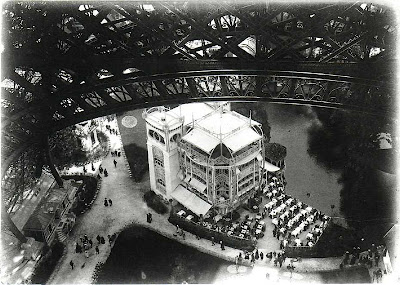

Sometimes you win the game. I recently discovered the above snapshot of the Eiffel Tower, taken in 1900 by the French novelist Emile Zola, where real magic is at work. Instead of clicking off the standard post card view of the site, Zola climbed to the tower’s first floor staircase, then shot straight down to capture an elegant period restaurant situated below the tower’s enormous foundation arches. And although only a small part of the Eiffel is in his final frame, it is contextualized in size and space against the delicate details of tables, chairs, and diners gathered below, glorifying both the tower and the bygone flavor of Paris at the turn of the 20th century.

Perhaps, for a well-recorded destination, the devil (and the delight) is in the details. Maybe we should all be framing tighter, zooming in, looking for the visual punctuation instead of the whole paragraph. Maybe all the “little stories” add up to a sum greater than that of the almighty master shot we originally went after. Despite the obstacles, we must still try to dictate the terms of engagement.

One image at a time.

Thoughts?

I WANT TO BE A PART OF IT…..

One belongs to New York instantly. One belongs to it as much in five minutes as in five years.

-Tom Wolfe

Old power, new power. The American Stock Exchange, a titan of the might of another era, stands in lower Manhattan alongside the ascending symbol of the city’s survival in another age, as the frame of WTC 1 climbs the New York sky. The tower, recently surpassing the height of the Empire State Building, will eventually top out, in 2013, at 1,776 feet. Single-image HDR designed to accentuate detail, then desaturated to black & white. 1/160 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 18mm.

THERE IS NO GREATER CANDY STORE FOR PHOTOGS than New York City. It is the complete range of human experience realized in steel and concrete. It is both a monument to our grandest dreams and a mausoleum for all our transgressions. It casts shadows that hide both joy and fear; it explodes in light that illuminates, in equal measure, the cracked face of the aged contender and the hopeful awe of the greenest newcomer. There is not another laboratory of human striving like it anywhere else on the planet. Period period period. Its collapses and soarings are always news to the observer. Bob Dylan once said that he who is not busy being born is busy dying. New York is, famously, always busy doing both.

I would give the greatest sunset in the world for one sight of New York’s skyline.

-Ayn Rand

Returning from Liberty Island and Ellis Island in November 2011, a packed tour boat’s passengers crowd the rail for a view of WTC 1, rising as the new king of the New York skyline.

This month’s announcement that the new WTC 1 (built on the site of the old 6 World Trade Center building, itself a rather short edifice) has finally surged past the height of the Empire State Building (a repeat champ for height, given the strange twists of history) is a bittersweet bulletin at best. Cheers turned to tears turned back into cheers. In the long-view, the inevitable breathe-in-breathe-out rhythm of NYC’s centuries-old saga, the site’s entire loop from defeat to defiant rebirth is only a single pulse point. Still, on a purely emotional, even sentimental level, it’s thrilling to see spires spring from the ashes. The buildings themselves, along with their daily purposes and uses, hardly matter. In a city of symbols, they are affirmations in an age when we need to remain busy being born.

Thoughts?

ALWAYS BE SHOOTING

Urban survivors or disposable legacy? Part of the world is always vanishing from view. What portions to visually preserve? And how best to tell these stories? 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 1000, 18mm.

PAUL DESMOND, LEGENDARY SAXOPHONIST for the Dave Brubeck Quartet, was famous for his wry replies to mundane questions from the press. Asked once “so, how are things going?”, he quipped, “Great. We’re playing music like it’s going out of style…..which, of course, it is.”

Beyond the cleverness of the statement, Desmond actually provided a corrolary to the ongoing state of photography. It is an art which is never “settled” into any final form, either in its mechanics or its aesthetic. Glass plates give way to roll film, which give way to digital storage, which will give way to..what? Recent trends in the forward edge of shooting hint at, among other things, bold new experiments in the direct exposure of chemically treated paper, minus lenses or shutters, resulting, in effect, in a camera-less camera. So now, what? A method so old that it’s new? So complicated that it’s totally simple? And where in these new crafts lie the art they might enable?

As image makers, we are really running down two parallel rails en route to obsolescence, since the world, as it can presently be seen, is passing away at the same lighting rate as our current means of documenting it. This is a constant for our art. When Eugene Atget recorded the last days of the Paris of the late 19th century, his methods for making the shots was fading out of fashion almost as quickly the dark, twisting streets he recorded. And when his protege, Berenice Abbott, undertook the same “mapping” of New York’s boroughs in the 1930’s (on assignment from various New Deal agencies), she, too was laboring against constantly improving methods for completing the book Changing New York, starting her massive project with a 60-pound view camera, and ending it with a new, lighter Rolleiflex miniature. She was also, understandably, racing against the wrecking ball of progress.

Worse, many places, such as the American southwest (where I live), hold the view that “old” is not “venerable”, but “in the way”….creating, for the shooter, a constant conundrum; what to visually archive, and in what way, and in what order?

The quiet death of Kodachrome, several years ago, proved a challenge for imagists the world over. If you were burning your last roll of this fabulous film forever, what shots would make your photographic bucket list? And how about expanding this scenario to include not just diehard “filmies”, but everyone? If there were an absolute deadline for imaging, a date beyond which no more pictures could be taken, ever, ever, what new urgency would inform your choices?

Sites like Ellis Island’s Great Hall have more than their share of caretakers. But how many other visual dramas will escape our viewfinders before they pass from the earth? 1/25 sec., f/6.3, ISO 100, 18mm.

It’s almost that dire already. Time hurtles forward and lays waste to everything in its path, including ourselves. Today, now, we are watching it erase neighborhoods, cities, forests, the shapes of nations, even the names of places. Even if we use our skills largely for cataloguing the general effect of these changes, we are nonetheless under the gun to fill our days with the grabbing of these fleeting glances. Even while we perpetually change how we capture, we must capture as much as we can, by any means available.

There is no mission statement stronger than the three words always be shooting. Because we are doing more than saving memories; we are, in fact, bearing witness. Whatever the subject, wherever we want to start chronicling the word around us, we need to be taking pictures.

Like they’re going out of style.

Thoughts?

THE GLORY OF THE INVISIBLE

I thought of trying to capture the vastness of Manhattan’s Strand Bookstore in a single wide shot, but finally preferred this view, which suggests the complexity and size of the store’s labyrinthine layout. 1/40 sec., F/7.1, ISO 500 at 18mm.

THE FRAME OF AN IMAGE is the greatest instrument of control in the photographer’s kit bag, more critical than any lens, light or sensor. In deciding what will or won’t be populated inside that space, a shooter decides what a personal, finite universe will consist of. He is creating an “other” world by defining what is worthwhile to view, and he also creates interest and tension by letting the view contemplate what he chose to exclude. What finally lies beyond the frame is always implied by what lies inside it, and it is the glory of the invisible that invites his audiences inside his vision, ironically by asking them to consider what is unseen….in a visual medium.

Each choice of what to “look at” has, inherent in it, a decision on what to pare away. It is thus within the power of the photographer to make a small detail speak for a larger reality, rendering the bigger scene either vitally important or completely irrelevant based on his whim. Often the best rendition of the frame is arrived at only after several alternate realities have been explored or rejected.

Over a lifetime, I have often been reluctant to show less, or to choose tiny stories within larger tapestries. In much pictorial photography, “big” seems to serve as its own end. “More” looks like it should be speaking in a louder voice. However, by opting to keep some items out of the discussion, to, in fact, select a picture rather than merely record it, what is left in the frame may speak more distinctly without the additional noise of visual chatter.

“If I’d had more time”, goes the old joke, “I’d have written you a shorter letter”. Indeed, as I get older, I find it easier to try and define the frame with an editor’s eye, not to limit what is shown, but to enhance it. Sometimes, the entire beach is stunning.But, in other instances,a few grains of sand may more eloquently imply the beach, and so enable us to remember what amazing details combine in our apprehension of the world.

Thoughts?