STEP RIGHT UP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY SHOULD ALWAYS OPERATE, at least to some extent, as a cultural mile marker, a chronicle of what time has taken away, a scrapbook of vanishings and extinctions. We make records. We bear witness. We take pictures of the comings and the goings.

One of the things that has been going, since the coming of the permanent, Disneyeque theme parks, those sanitized domains of well-regulated recreation, is the great American carnival, in all its gaudy and ever so slightly dodgy glory. Loud, crude and exotically disreputable, these neon and canvas gypsy camps of guilty pleasure once sprang up in fields and vacant lots across the nation, laden with the delicious allure of original sin, that is, if the first apple of Eden had been dipped in shiny red candy. We came, we saw, whe rode, we ate, we clicked off millions of snapshots on our Kodak Brownies.

The thing that made it all so magical was geography. Unlike Seven Flags or Cedar Point, the carnival came to us. Like the circus, the carnival was coming to your town, just down your block. That meant that your drab streets were transformed into wonderlands in the few hours it took for the roustabouts to assemble their gigantic erector sets into rickety Ferris wheels and Tilt-a-Whirls. And then there was the faint whiff of danger, with rides that made dads ask “is this thing safe?” and crews that made moms repeat horrific tales of what happens to Little Children Who Talk To Strangers.

It was heaven.

The images seen here are a partial return to that sketchy paradise, with the arrival in my neighborhood, this week of a carnival in an area that hasn’t hosted one in well over a decade. It’s almost as if Professor Marvel just ballooned in from Oz, or Doc and Marty had suddenly materialized in the DeLorean. It’s that weird. Four days in, and I’m there with a different lens each time, sopping up as much trashy delight as I can before the entire mirage folds and all our lives return to, God help us, normal. Photographs are never a substitute for reality, any more than a hoof print is a horse. But when dreams re-appear, however fleetingly, well past their historical sell-by date, well, I’ll settle for a few swiftly stolen souvenirs.

BOOK BINDINGS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE BUILDING YOU SEE HERE may not, on first glance, match your sensory memory of what a “public library” is supposed to look like. However, step into this amazing complex on West Georgia Street in Vancouver and you will certainly see, from every angle of its curvy vastness, the public….buzzing away at research, cozying next to comfy reads in cafes, tucked away in private warrens of study and solitude.

The venerable past: the mezzanine at the central branch of the Metropolitan Library in Columbus, Ohio (opened in 1907).

One of photography’s functions is to chronicle the public space that mankind creates, and how it occupies that space. And visually, there can be no greater illustration of the changes in how that space is defined than in the architectural evolution of public libraries. More than mere warehouses for books, libraries were the first common gathering places in our young republic, no less important than legislatures or marketplaces. Indeed, we built many libraries to be brick and mortar celebrations of learning, grand, soaring temples to thought, arrayed in oak clusters, dizzying vaults, sprawling staircases, and mottoes of the masters, wrought in alabaster and marble. To see these spaces today is to feel the aspiration, the ambitious reach inside every volume within the stacks of these palaces.

The library, in the twenty-first century, is an institution struggling to find its next best iteration, as books share the search for knowledge with a buffet of competing platforms. That evolution of purpose is now spelled out in new kinds of public space, and the photographer is charged with witnessing their birth, just as he witnessed the digging of the subways or the upward surge of the skyscraper. New paths to fortune are being erected within the provocative wings of our New Libraries. Their shapes may seem foreign, but their aim is familiar: to create a haven for the mind and a shelter for the heart.

There are legends to be written here, and some of them will be written with light…..

MIND OVER MACHINE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I no longer believe that there is such a thing as objectivity. Everyone has a point of view. Some people call it style. But what we’re really talking about is the guts of a photograph. When you trust your point of view, that’s when you start taking pictures.

Annie Leibovitz

NONE OF MY FAVORITE PHOTOGRAPHERS are primarily technicians. Certainly I value the basic mastery required to extract the best mechanical performance out of one’s camera, but I don’t think that a lack of such knowledge necessarily dooms a picture. I do, however, believe that no lens on earth can compensate for a deficiency of mindfulness in the photographer. I cite Annie Leibovitz here because I believe she deftly walks the creative tightrope between an essential understanding of how photography works and a poetic gift for finding how it works for her. She knows her gear as much as is necessary: she knows her heart as much as is possible.

On a shoot, once I’ve established that the camera is on and the lens cap is off, I endeavor to disconnect with the gear and re-connect with the twelve-year-old who first gasped as he gazed through a viewfinder. That kid knew that everything was possible. More precisely, he didn’t know enough to realize what wasn’t possible, and so blithely proceeded to try it all. His older brother (me) wants to point out that the light is wrong, that he packed the wrong lens, and that, maybe, he just doesn’t actually know how to make the picture. Worse yet, he might know just enough to worry that his work won’t register with others. The twelve-year-old doesn’t care.

My photo gods are all people who know all the things that can go wrong with a shot and take the shot anyway. They are not waiting for their moment. They are jumping out of the plane and trusting the chute to open. More to the point, they are trusting themselves.

“I still have a very limited knowledge of the technical side of photography”, Linda McCartney wrote in 1992, looking back upon her amazing body of documentary work in the rock demimonde of the ’60’s. “I prefer to work by trial and error because some of my best pictures have come precisely because I didn’t know enough. By having the “wrong” setting, I’ve actually come up with something good….”

ALL ON ME

PHOTOGRAPHERS ARE FREQUENTLY ASKED to define a “bad” picture, or, more specifically, the worst picture they themselves ever shot. The question is a bit of a logic trap, though, since it typically tricks us into naming something that failed because the subject was moribund, or because we mis-read the light, the aperture, the composition. The trap further reasons that, if you have checked off all those boxes, you should end up with a great picture.

But all of that is bug wash. What makes a picture bad is when you were not ready to take it….. but you took it anyway.

Sometimes the problem is ignorance: you simply aren’t old or wise enough to know what to do with the subject. Other times, you have substantial barriers between you and an effective story, but you try to drill past what you can’t fix. And, you can no doubt add your own list of things that, ahead of the shutter click, should scream, “not now”. Try to make the picture before either the conditions or you (usually you) are right, and you lose. Just as I lost, in great big neon letters, with the mess you at above left.

In 2016, I visited the Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, a venerable colonial-era home which sits right next to the small footbridge that served as the site of the first major battle of the Revolutionary War. What excited me most, however, was that it had served as a temporary home for the young Ralph Waldo Emerson, and that he had written Nature, the first of his great works, while living there. And to really put the cherry on the sundae, the house still contains the small writing desk he used to do it.

The house is lit only with indirect window light during the day, but with a fast prime lens and a decent eye, there’s more than enough soft illumination to work with to produce decent results (see left). In fact, just before my tour was to head into the room containing the desk, I had already harvested quite a few usable shots…so many, in fact, that I was getting teased by the others in the group…the usual “oh, another picture?” stuff. Uncharacteristically, I began to worry about whether I was holding everyone else up, and thus started to hurry myself, to shoot not as I intended, but in deference to what I thought others would like. By the time I got to Emerson’s chair, the light, my lens, even my own experience were all useless to me….because I wasn’t ready to shoot….but did anyway.

The house is lit only with indirect window light during the day, but with a fast prime lens and a decent eye, there’s more than enough soft illumination to work with to produce decent results (see left). In fact, just before my tour was to head into the room containing the desk, I had already harvested quite a few usable shots…so many, in fact, that I was getting teased by the others in the group…the usual “oh, another picture?” stuff. Uncharacteristically, I began to worry about whether I was holding everyone else up, and thus started to hurry myself, to shoot not as I intended, but in deference to what I thought others would like. By the time I got to Emerson’s chair, the light, my lens, even my own experience were all useless to me….because I wasn’t ready to shoot….but did anyway.

And so you behold the unholy mess that resulted: lousy contrast, uneven exposure, muddy texture (is the chair made out of wood or Play-Doh?), tons of noise, indifferent angle, and, oh yeah, garbage focus. Worse yet, the psyche I’d put upon myself was so severe that I didn’t slow down for a more considered re-do. No, I rejoined the group like a polite little camper, and left without what I had come for.

And that is all on me, and thus an important entry in The Normal Eye, an ongoing chronicle which is designed to emphasize personal choice and responsibility in photography, versus just hoping well-designed machines will compensate for our lack of concept or intention. This is not easy. This is ha It’s no fun realizing that what went wrong with an image was us.

But it’s a valuable thing to own. And to act upon.

(RE)SHAKE IT LIKE A POLAROID

By MICHAEL PERKINS

OVER THE PAST FEW DECEMBERS, The Normal Eye has marked the holidays by recalling classic Christmas advertisements from the Eastman Kodak Company, the first corporation to merge consumers’ seasonal sentiment with the promotion of camera sales. We’ve had fun revisiting examples of the firm’s amazingly successful “Open Me First” campaign, which cheerfully asserted that, basically, it ain’t Christmas until someone puts a Kodak under the tree.

This year, however, seems to argue for a new wrinkle in our tradition, with the long-anticipated resurrection of the Polaroid corporation, or at least its Christmas ghost. The strange saga began in 2008 when Polaroid decided to discontinue the production of its iconic instant film, leaving a half-century’s worth of global users stranded. Enter the entrepreneurial trio of Florian Kaps, Andre Bosman, and Marwan Saba, who bought as much of the company’s factory hardware and film-making process that still remained after Polaroid had begun scrapping parts and burning files. Sadly, most of the sacred secret film recipe had already been destroyed, meaning that the team’s new company, dubbed The Impossible Project, had to painstakingly reverse-engineer the production process, eventually creating an instant film that was much closer to the quirky, low-fi look of Lomography cameras than the precise instruments Polaroid produced in its heyday.

For the next seven years, Impossible Project instant film shot off the shelves to feed the world’s aged inventory of SX-70’s and One-Steps, drawing praise for preserving the feel of film and drawing fire for what was actually pretty crappy color rendition and slooooow development time. Finally, in 2017, Impossible purchased the last remnants of Polaroid’s intellectual property, allowing it to begin manufacturing brand-new cameras for the first time in years and rebranding the company as Polaroid Originals. Christmas 2017 would herald the arrival of the Polaroid OneStep 2, a point-and-shoot quickie designed to compete with other mostly-toy cameras cashing in on the instant film fever. The Ghost Of Shaken Snaps Past walks amongst us once again.

And so, Polaroid is dead and long live Polaroid. The above 1967 Christmas pitch for the original company’s full product line (read the fine print) gives testimony to the incredible instruments that once bore the Polaroid name. You can’t go home again, truly. Not to live, anyway. However, an occasional 60-second visit can be fun.

Strange colors and all.

NO SECOND ACT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS SOMETHING TRAGIC, AND CONFOUNDING, in America’s longstanding reluctance to re-use and re-purpose its historic infrastructure. This ever-young nation seems to have an allergic reaction to preservation, as if the physical artifacts of its heritage contained some kind of dread plague. As a consequence, buildings that have figured most prominently in the story of our nation’s amazing evolution fall…. first to neglect, then to the wrecking ball.

Photography is a way to bear witness to what Gore Vidal called “the United States Of Amnesia”, a way to document lost opportunities and wasted potential across the fifty states. Miles of once-vital roads that no longer lead anywhere: blocks of neighborhoods that now howl and whistle in a dead wind: acres of buildings that once housed history instead of cockroaches and cobwebs. All is ripe for either revelation or regret at the point of a camera.

Columbus, Ohio’s original air terminal building, opened in 1929 with hoopla and help from both Amelia Earhart and co-founder Charles Lindbergh, is one such location. Created as part of the country’s first fledgling attempt at a transcontinental air service (and this, only two years after Lindbergh’s astonishing solo flight to Paris) “Port Columbus” was solid proof that the air age was real.

Real enough, in fact, that a mere nineteen years later, the city’s air traffic had grown so rapidly that construction began on a shiny new international hub, big enough to accommodate a mid-century tourist boom, the jet era, and an explosion of international travel. The 1929 terminal was shuttered, living a few latter-day half-lives as offices for one short-term tenant or another, finally coming its silent rest on the Port’s back property, its legacy given half-hearted lip service with the obligatory plaque on the door.

Full disclosure: Columbus, Ohio was, for most of my life, my hometown. It is, among other things, a city of many firsts, a vital test market of ideas for everything from ATMs to hula hoops. And while I know that new uses won’t be in the cards for all historically important buildings there (or, indeed, anywhere), I am glad, at least, that, as photographers, we are privileged to say of such places: look here. This happened. This was important.

It’s often said that there are no second acts in American lives.

That’s tragic. And confounding.

ONE-TRICK PONIES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YARD SALES AROUND THE WORLD abound with unwanted gadgets that, just a few year prior, seemed utterly indispensable, be they electric olive pit extractors or deluxe coffee foam skimmers. You know the kind of toys I mean– those glorious, gleaming, largely single-function devices that dazzle us on all-night infomercials and seem like depraved decadence after we’ve hooked them up a few times and found that, hey, you can still access a new batch of carrots with a 79-cent manual can opener and use the regained counter-space for something more essential. Like food.

And, of course, these one-trick ponies of gimmickdom are not only found in the world’s greatest kitchens, but also on dusty shelves in the closets of disaffected photographers, who, like any humans, are subject to the lure of the new. Hey, I get it. It’s fun to have a special, fresh, whirly-twirly glowing godalmighty gizmo, that little add-on that creates amazing effects, amusing simulations, crazy textures. Lens manufacturers are particularly great at getting the fishhook into the mouths of photogs when it comes to toy time, since no one responds better to the latest optical trick. But, as in the case of the pit extractor, you have to ask yourself how much permanent, sustaining, everyday use you will get out of a given piece of gear.

One great way lens manufacturers have devised to separate you from your cash is to introduce a new version of a classic or “art” lens that re-creates an effect that is associated with the halcyon days of early photography. One such lens is the Petzval, named after Josef Petzval, who developed it around the 1840’s. The optics of the Petzval are particularly seductive for portraitists, as they separate your subject from the ambient scenery by rendering it sharp at the center while making all background information look like a swirling blur. Very artsy, very specialized, and very, very expensive.

Neo-Petzvals are all-manual (niche market #1), metal bodied (niche market #2) and gorgeously nostalgic (niche market #3), looking like something Ahab would use to track Moby Dick around the seven seas. These beauties, which, again, can only make one kind of image at one focal length, can cost upwards of $700 through Lomography.com. Companies like Lensbaby can create the same effect for around $149 and more than a few phone apps can deliver the same thrill for $2.99 or under. But the cost is almost irrelevant. What counts is how much you will actually use the thing.

You have to decide what your approach to equipment is, making a personal calculation based on what you most need to do for you. My own version of this riddle is based on how much I can do with how little, making me prefer lenses and appliances that can multi-task. However, there’ll always be days when life’s hella hectic and you just haven’t got time to scrape your own coffee foam. As usual, the answer lies in the kind of photography that snaps your personal shutter. Your pictures, your playthings.

CAN’T GET THERE FROM HERE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE “U.S.A.” OF THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY was, in every way, a collection of separate and unconnected “Americas”. Cities were fewer in number, and the ones that did exist were hermetically sealed off from each other, each in their own orbits in a way that would end when telegraph wires and railroad tracks annihilated distance on the continent forever. At one end of the 1800’s, each town and village was its own distinct universe; at the other end, it was only one of many dots on a line chain-linking the nation as one entity.

In the 21st century, there is only spotty evidence of the days when your town was, in a very real way, the predominant version of “the world” to you. The terms of survival were so very different. “In town” and “out of town” were measured in blocks, not miles. There was a pronounced sense of “how we do things around here”. Local accents were a clearer stamp of identity. News from outer regions arrived slowly. People’s lives impacted each other directly. And the towns first canvassed by photographers reflected the isolation of one city from another, for good or ill.

My parents met each other in a town that started small and stayed that way. It’s contracted now, the way a grape shrinks to a raisin; there is still enough of its old essence to identify what it was, but no hope for a future that resembles the past in any remote manner. I love making photographs of places in America where the feeling of apartness is still palpable. It is harder to be hidden away now. We are all one coast-to-coast nervous system, with impulses crossing the void in nanoseconds. The places which still say “our town” are often baffled off from other towns by raw geography….the mountains someone forgot to cross, the rivers no one wanted to ford. And, in the towns walled off by those last remaining barriers, as in this view of Truckee, California in the Sierras, there are still stories to be told, and images to be captured.

I was struck in this picture by how close the residential and business parts of town were to each other, long before we all started spreading out and, well, getting away from each other. It creates a longing in me for something I can’t fully experience, and a desire to use my camera to come as close as I can.

IT HAPPENED RIGHT HERE. DIDN’T IT?

After The End, Before The Finish (2017). The back porch to Virginia City, Nevada, once one of the richest towns on the face of the earth.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AMERICA HAS NO LOVE OF INTERMEDIATE CHAPTERS. We’re big fans on huge, new beginnings of things. We are likewise fascinated by catastrophic finales. By contrast, the stories that take place between the first and last episodes of things are like flyover cities between the coasts.

Consequently, we tend to generate photographic tonnage when the Bright Shiny New Mall cuts its opening day ribbon, and crank lots of frames on the day the Sad Old Mall is razed to the ground, but not much quotidian stuff. There may indeed be less drama in the day-to-day goings-on in towns, public works, and other human endeavors. or maybe we just bore easily. Or maybe we haven’t learned to detect the tiny stories that rise and fall between the more obvious bookends of history.

Boom and Bust are big news to photographers. Humming Along Normally, not so much.

Virginia City, Nevada typifies what Americans call Ghost Towns, places which ran their life cycle from explosion to collapse but still physically exist in some way. Some are mere hollowed-out ruins crumbling in the dust, while others, like Virginia City, have survived as commercial entities (spelled: tourist traps) selling nostalgia. They make money recalling how they used to make money, which, in the case of V.C., was mining silver. This little bus stop of a town was once one of the wealthiest places on the planet, ripping ore out of the ground and sending it all over the world at a rate that minted a new millionaire every few minutes. Virginia City had its own short line railroad making freight runs hundreds of times each day. Its well-heeled lords imported materials from every continent to appoint opera houses, churches, hotels and saloons with glitter and grandeur. And the city created one of the most progressive elementary schools in the nation, equipped with central heating, flush toilets, water fountains, and individual student desks….in 1876.

Ghost towns are the walk-through museums, the pickled cadavers of American life. They’re finished but they aren’t through. There is a bright coat of paint replicating the gaiety of better times, but, beyond the fro-yo stands, ersatz whiskey joints and souvenir shoppes, the skeleton of a very different daily life is still visible. And a well-aimed camera can still summon a degree of Boom within the Bust.

A FUNERAL AND A BIRTHDAY

John Lennon and Ringo Starr inspect the assembly of the celebrity diorama that would be the main set piece for the Sgt. Pepper album cover, 1967.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ANY COMPLETE DISCUSSION OF THE LEGACY OF THE BEATLES‘ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, marking its fiftieth anniversary in 2017, will include voluminous analyses of its ground-breaking production technique and breakthrough approach to musical composition, and rightfully so. But this most fundamental of pop culture events of the 1960’s must also be thought of in purely visual terms, since many of us first encountered it as an amazing, challenging image.

In truth, the collaboration between Pop Art designer Peter Blake and studio photographer Michael Cooper, with its ad-hoc gathering of cardboard celebrities grouped around a gravesite with the word BEATLES spelled out in blossoms, is the first act of a two-act play. The cover set the same audacious terms of engagement that the record inside the sleeve would abide by: Art and Music are what we say they are: We, the Beatles, are in complete charge of our music, our image, and our connection with the audience: we will not have “a” style, but will hybridize whatever schools of thought come to hand, from modes of composition to instruments to shifting patterns of Past, Present, and Future to coloring outside the lines of even our own culture. I read the news, today, oh, boy, and it said there are no more rules: there are no more walls. The stage can no longer hold us. Only the studio itself is vast enough to contain what we have to say.

The cover of Sgt. Pepper made a stunning break with the accepted practices used by record labels to market their goods. Quite simply, the suits in the front office were no longer in charge of the pictures. And what of that picture, or, more accurately, that picture of pictures? Is it a tribute? A put-on? A serving of notice that the Beatles are dead, long live the Beatles? Yes, yes, and hell, yes. Pepper made it plain, once and for all, that album covers, which had begun in the 1930’s as basic advertising sleeves for the goods within, could be venerated, influential, and, yeah, framed on some freak’s wall. Like, you know, man, art.

And, if Cooper and Blake were drawing a line between eras for the record world, they were doing so to an even greater degree for photography, which, in 1967, was still considered by some as more craft than art. Within a few years after A Day In The Life‘s long, ringing super-chord, museums were mounting shows by Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Robert Frank, right alongside the painters, and directly adjacent to people like Warhol who constituted categories all their own.

Just as Alice In Wonderland is somehow legless without John Tenniel’s illustrations, Sgt. Pepper’s’ outside will always be wedded to its inside, and vice versa. As the most popular multimedia product in commercial history, it owes much of its titanic impact to the image of four oddly costumed men with four strangely new mustaches and one big message: there is more to us than meets the eye. Like the best of photography, the picture issues a challenge. Nothing is real.

And nothing to get hung about…….

MR. KITE HAS LEFT THE BUILDING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY’S PRINCIPLE BENEFIT IS THE STEALING AND PRESERVATION OF THE FLEETING. That was the miracle that originally astonished the world, the ability to arrest time, to selectively snatch away droplets of the infinitely flowing river of moments and keep them in a jar. And as the young art flourished and began to flex, it proved capable of not only grabbing individual instants, but chronicling the passing of entire modes of life.

As the prairie was settled, as the great distances of the planet were traversed and tamed, as the horse gave way to the car, and as the country mouse became the city mouse, photography laid down mile markers, clearly labeled “this is”, “this is going away” and “this was”. As a consequence, we now have a visual record of worlds and ways of living that have already long since gone extinct. We rifle through shared and inherited images that mark the passing of empires, fashions, movements.

This is all, of course, beyond obvious, but there are times when photographers are more keenly mindful that something big is in the process of winking out. I experienced such a moment a few days ago with the news that Ringling Brothers’ circus was shuttering its operations after more than 150 years, ringing down the curtain on a mixed record of extravaganza and exploitation, depending on where you stand on the issue. Whether circuses were a wonder or an abomination or both, they represented a distinctly analog kind of entertainment, a direct tie between sensations and senses that is one of the last traces of 19th-century culture.

Along with world’s fairs, carnivals, vaudeville, even rodeo, the circus serves as a strange relic of a time when the arrival of the Wells Fargo wagon or the pitching of the Chautauqua tent could be the height of the social season in many a town. The visually rich pageant of having dozens of clowns, acrobats, and performing beasts parade right down your main street was, in the days before mass media, pretty heady stuff, and, even at its twilight, it still has a powerful, if quaint, pull on the imagination. All of this is fertile ground for the photographer/chronicler.

It’s now fifty years since John Lennon transcribed the text from an old circus poster to evoke a vanished era with the song Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite, overdubbing the music track with a montage of calliopes and hurdy-gurdys to paint a very visual piece of audio. To this day, I can’t hear the tune without concocting my own mental photo of prancing ponies and carnival barkers. Mr. Kite may already be retiring to his dressing room, as are so many analog forms of entertainment. But we have the pictures. Or we need to start making them.

EXPEDITIONARY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“THE WORLD IS TOO MUCH WITH US“, goes the classic Wordsworth sonnet, which points out that, not only do we miss seeing much of that which is most essential in our lives, we may not even know what we don’t know. And, in the general realm of art, and specifically in the art of photography, what survives in our visual record is limited to what we believed was important…at the time.

Reality is constantly morphing, and try as we might to use our cameras to bear witness to The Big Stuff, we neglect the fact that much of which we regard as anecdotal, as the “little stuff”, might just be biggest of all in the long run. The decisions required by art in the midst of history are terrifying. What image to make? What event to record? What kind of case to make for ourselves, as agents of our time?

This year, 2017, marks the one-hundredth anniversary of the United States’ entry into what was then called The Great War. The term was grandiose, and dire, denoting a conflict that was, for the first time, truly global, a tsunami of slaughter so vast that it had been, heretofore, simply unimaginable. And yet, in time, the phrase was abandoned, because we had rendered it obsolete, by the obscene act of ordering up a sequel. And so we began to take the greatest mass murders of all time, and merely number them, as if they were nothing more than sequential lines on an endless horizon. And with these wars, for the first time, came pole-to-pole photographic coverage, an unprecedented, ubiquitous visual chronicle. Again, the questions: did we get it right? Did we make the pictures that needed to be made?

Who can know? The blood that soaks the battlefields also waters the grass that eventually covers them over. The din of death becomes the silence of lost detail. Photographs curl, tear, burn, vanish, become memories of memories. We hope some small part of our art becomes an actual legacy. And again, we ask: what did we miss? Whose stories did we neglect? Which evidence did we ignore? The world, always too much with us, forces us, now as then, to edit on the fly, hoping we can at least strive, against all odds, to be reliable narrators.

AT WAR WITH THE OBVIOUS

“I had this notion of what I called a democratic way of looking around, that nothing was more or less important. It quickly came to be that I grew interested in photographing whatever was there, wherever I happened to be. For any reason.” –William Eggleston

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MOST PHOTOGRAPHERS ARE NOT PRIME MOVERS, in that the majority of us don’t personally carve out the foundations of new truths, but rather build on the foundations laid by others. Art consists of both revolutionaries and disciples, and the latter group is always the larger. With that in mind, it’s more than enough for an individual shooter to establish a single beachhead that points the way for those who follow, and to be able to achieve two such breakthroughs is almost unheard of. Strangely, one of the photographers who did just that is, himself, also almost unheard of, at least outside of the intellectual elite.

William Eggleston (b. 1939) can correctly be credited as one of the major midwives of color photography at a time that it was still largely black and white’s unwanted stepchild. Great color work by others certainly preceded his own entry to the medium in 1965, but the limits of print technology, as well as a decidedly snobby bias toward monochrome by the world at large, slowed its adoption into artsy circle by decades. After modeling himself on the great b&w street shooters Robert Frank and Henri Cartier-Bresson, Eggleston practically stumbled into color, getting many of his first prints processed at ordinary drugstores rather than in his own darkroom. His accidental discovery of the dye-transfer color process on a lab’s price list sparked his curiosity, and he soon crossed over into brilliantly saturated transparencies, images bursting with radiant hues that were still a rarity even in major publications. Eggleston’s work was, suddenly, all about color. That was Revolution One.

Revolution Two emerged when he stopped worrying about whether his pictures were “about” anything else. Eggleston began what he later termed his “war with the obvious”, eschewing the popular practice of using photographs to document or comment. His portfolios began to center on mundane subjects or street situations which fell beneath the notice of most other shooters. The fact that something was in the world was, for Eggleston, enough to warrant having a picture made of it. A street sign, an abandoned tricycle, a blood-red enameled ceiling..anything and everything was suddenly worth his attention.

Reaction in the photographic world was decidedly mixed. While John Szarkowski, the adventurous director of photography at the New York Museum Of Modern Art, marveled at a talent he saw as “coming out of the blue”, making Eggleston only the second major color photographer to exhibit at MOMA, others called the work ugly, banal, meaningless. Even today, Eggleston’s subjects elicit reactions of “…so what??” from many viewers, as if someone told them the front end of a joke but omitted the punch line. “People always want to know when something was taken, where it was taken, and, God knows, why it was taken”, Eggleston remarked in one interview. “It gets really ridiculous. I mean, they’re right there, whatever they are.”

However, as can frequently happen in the long arc of photographic history, Eggleston’s work reverberates today in the images created by the Instantaneous Generation, the shoot-from-the-hip, instinctive shooters of the iPhone era who celebrate randomness and a certain hip detachment in their view of the world. As a consequence of Eggleston’s work, images have long since been freed of the prison of “relevance”, as people rightfully ask who is qualified to say what a picture is, or if there is any standard for photography at all. Thus does the obvious become a casualty of war.

RICH, TALENTED BOY MAKES GOOD

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE MOST APPEALING FEATURE OF EVERY NEW ART is that, for a while, everyone participating in it is an amateur. Because a new art has no history, it has no history-makers….no professionals, no celebrated artistes, no one who is doing it better. Everyone is, briefly, in the same “how-do-you-work-this-thing?” boat.

Of course, eventually, some ornery cuss or another begins to figure out how to progress from stumblebum to star, and then everyone’s off to the races. Photography, like other infant arts, began as a tinkerer’s toy, sprouting an occasional outlier genius here and there, until the pool was fairly crowded with People Trying To Make Their Mark. And one of those first mark-makers was not yet out of short pants when his pictures began to be the embodiment of the phrase “and a little child shall lead them.”

His name was Jacques Henri Lartigue, and, whatever else formed his strong visual sense, it certainly wasn’t the nobility of poverty, born, as he was, in 1894 in France to upper-class wealth and the privilege that went with it. His photographic muse thus contained none of those inspiring Lean, Hungry Years or Hard-won Real World Experiences that we associate with mature art; the kid was just born with an instinctually strong knack for composition, and what he chose to compose just happened to be the activities of the Rich and Famous….in other words, everyone he hung out with.

Lartigue’s social set was the class every other social set in France aspired to; the people who seasoned at the Rive Gauche, the people who competed in lawn tennis tournaments, the country’s first race car drivers and aviators. Armed with a simple gift camera, and taught processing by his father, Jacques began snapping the world around him at age seven, maintaining journals that contextualized the images, bookmarking his family’s gilded role in the newborn twentieth century.

Gifted with an eye for photographic narrative, Lartigue nevertheless segued into painting, where he spent virtually his entire adult life. In fact, it was not until a friend showed some of Jacques’ photos to John Szarkowski, director of photography at the New York Museum of Modern Art, that Lartigue had his first formal photographic exhibition, in 1963, when he was sixty-nine.The show led to international recognition of his untutored yet undeniable talent, as well as a few prize portrait commissions and a second social career with the same elite one-percenters with whom he had rubbed elbows as a boy. One of his final collections, Diary Of A Century, was published in cooperation with Richard Avedon in 1978. He died a late-blooming “overnight success” at ninety-two.

What began for Jacques Henri Lartigue as family snapshots became one of the most important chronicles of a vanished world, and thus the best kind of photojournalism (or sociology, depending on your college major). For shooters, this boy of privilege remains the romantic ideal of the talented amateur.

THE BOND

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY CONSUMER, Apple, Inc. seems to stand alone in its ability to define a market for a product, fill that market before anyone else can, and engineer the very need for that product in its customers. Apple has not only wrought great things, it has convinced us that, even though we couldn’t have imagined them ourselves, we can no longer imagine life without them. That bond between provider and user seems unique in the history of the world.

But it’s been done before.

In the 1880’s, when George Eastman perfected the world’s first practical photographic roll film, the idea of owning one’s own camera was quaint at best. Early photo images were created by talented, rich tinkerers and the first few professionals, making photographers a small, select brotherhood. Even so, Eastman’s boldest idea was not his film but the affordable means to make a film user out of the average man. The new Eastman Kodak company, like Apple, conceived of a market, filled it almost exclusively with their own products, and closed the deal by proceeding to teach people not only how to use their Kodaks but how to link photography with a full and happy life.

Over the last few Decembers, I have dedicated pages of The Normal Eye to the decades-long love affair between Kodak and the world that it trained to treasure photographs. Its marketing reached its creative zenith with the “Open Me First” Christmas campaigns of the 1950’s and ’60’s, which posited the idea that nothing wonderful could happen in the life of your family, especially on The Big Day, if you failed to record even a moment of it on Kodak film.

Kodak used the most popular children’s book chracters of the 1800’s, the “Brownies” to sell kids’ cameras.

However, Kodak’s mastery of emotional messaging was in full flower generations before the “Open Me First” pitches for Instamatic cameras and Carousel projectors. Long before television and radio, the company’s persuasive use of print carried much the same appeal: if it’s important, it’s worth preserving, and we have the tools and talent you need to do it. Kodak cameras quickly became positioned as The Ideal Christmas Present, as the company targeted newlyweds and young parents with their upscale models and cultivated the youth market with their $1 line of children’s cameras. In an early example of inspired branding, the kids’ models were marketed with the names and images of illustrator Palmer Cox’ runaway juvenile book characters, the Brownies, playful elves who were featured on Kodak packaging and ads for more than a decade, helping launch the world’s most successful lines of cameras, in continuous production from 1900 to 1980.

Not even Apple in all its marketing glory has managed to align itself so solidly with the emotional core of its customers in the same way that Kodak, for nearly a century, forged a bond between its users and the most emotionally charged time of the year. In so doing, they almost singlehandedly invented the amateur photographer, fueling a hunger for images in the average Joe that continues unabated.

SIMPLE GIFTS

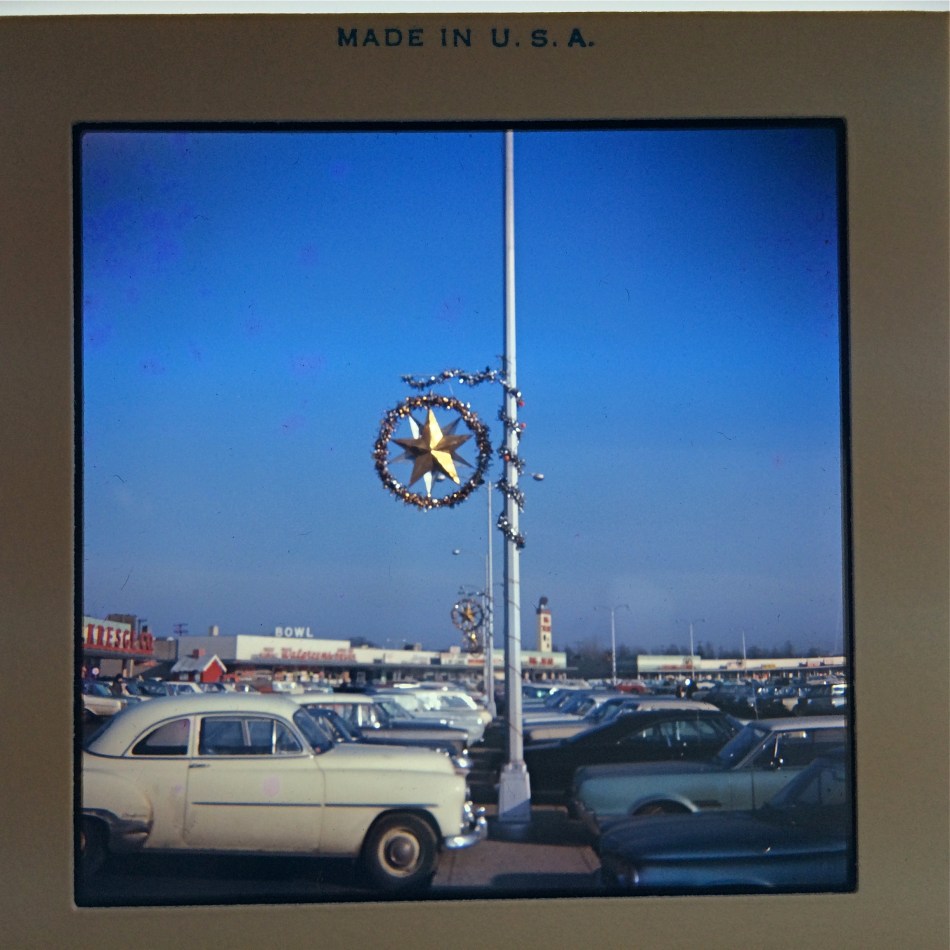

All dolled up for the holidays: Northern Lights Shopping Center, Columbus, Ohio, 1966. And, yes, there is WAY too much sky in this shot.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THANKSGIVING WEEK USUALLY DEPUTIZES WRITERS OF EVERY VARIETY to generate lists of things the author is thankful for, everything from baby puppies to the designated-hitter rule, all enveloped in the gold glow of gratitude. Photographers are usually not enlisted for these rosters of wonderfulness, but, if you make pictures long enough, you will, no doubt, have a list of very specific items that warm your heart.

Over a lifetime, I have generally been grateful for photography’s consistent ability to excite my senses, challenge my thinking, and create the addictive sensation known as surprise. I’m grateful that George Eastman introduced the first practical roll film, taking photography from the hands of the few and giving it to the world at large. I’m glad that images have found languages with which to speak to people, languages that surpass the power of speech. I’m glad that photographs stitch together links across every gulf of human experience. And I’m thankful for the pictures that enraged me to action, that gladdened me to tears, that encouraged me to make more pictures of my own.

I’m grateful for the men and women who have created the greatest visual art form the world has ever known. You can sub your own gallery of gods, but mine includes Ansel Adams, Berenice Abbott, Garry Winogrand, Alfred Stieglitz, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gordon Parks, Margaret Bourke-White, Edward Weston, Robert Frank, Edward Steichen, Robert Capa, Diane Arbus, Weegee, Walker Evans, Julia Margaret Cameron, W.Eugene Smith, Dorothea Lange, Richard Avedon, Annie Liebowitz, and, most importantly, the millions of invisible eyes and hands out there cranking, out there living by one unshakable credo: Always be shooting.

I thank the photo gods for images of my parents, first as sweethearts in the aftermath of World War II, then as newlyweds in the ’50’s, then as Mommy and Daddy in the Space Age, and presently as the great long-distance runners of romance, still mad for each other at 66 years and counting. I thank fortune for the bunny ears and hamming and mugging and bright toothy giggles of my own children, frozen now in their newness and their hunger for life. And I incidentally thank luck for Kodachrome, quick-charging batteries, fast lenses and a few moments in which I swung around, just in time, and got the shot.

The camera is many things…charmer, chronicler, narrator, witness, liar, magic wand. It gains all these special powers in the hands of people. Photographs are measures of who we are, what we care about, and what we want time to say about us after we’re gone.

Lots to do, lots left to attempt.

Lots to be thankful for.

PROOF POSITIVE (AND NEGATIVE)

How charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably and remain fixed upon the paper! And why should it not be possible? I asked myself. –William Henry Fox Talbot

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IMAGINE THAT, IN ADDITION TO MAKING THE AUTOMOBILE PRACTICAL AND AFFORDABLE, Henry Ford had also been the world’s foremost racing driver. Or that Rembrandt had also invented canvas. The history of invention occasionally puts forth outliers who not only envision an improvement for the world, but become renowned as the best, first models for how to use it. The early days of photography saw several such giants, tinkerers who nudged the infant technique forward even as they became its first artists.

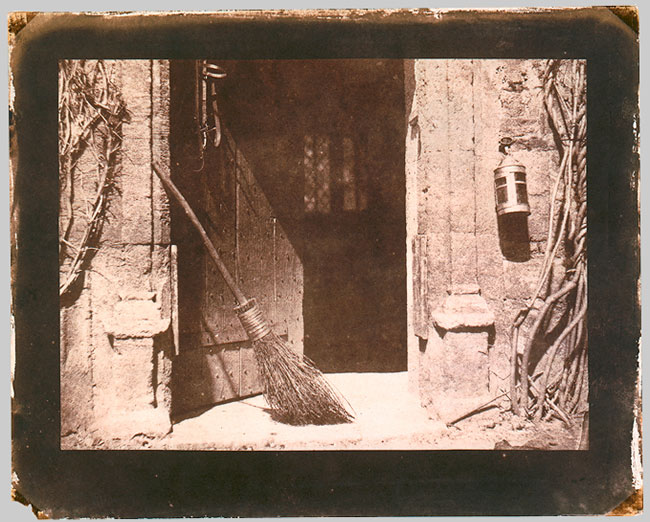

William Henry Fox Talbot, Trees And Reflections (1842). The master technician was also a masterful artist.

Unlike the telephone or the incandescent bulb, there was, for the camera, no single parent, but rather a series of talented midwives who massaged the young art from exotic hobby to mass movement, the most democratic of all art forms. Thus, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) was not the first person to use light and chemistry to permanently fix and preserve images. But, without his contributions, printed photograph might never have evolved, nor would the negative, the easiest method for printing endless numbers of copies from a single master.

Talbot’s work began as a way to improve upon the daguerreotype, which dominated the photographic world in the early 1800’s and which was, as a positive image printed directly on glass, literally one of a kind, barring duplication or distribution. If photography were to be widely practiced, Talbot reasoned, a practical method had to be created to allow photos to be made from photos.

Talbot’s first attempts consisted of ordinary typing paper coated in a solution of salt and silver nitrate. The resulting silver-chloride mixture was highly sensitive to light, darkening as it was exposed, and registering the light and dark values of a subject backwards, as a negative. However, over the long exposures needed at the time, the darkening process often accelerated to make the image completely black, so Talbot had to experiment with other chemicals to render the process stable, to develop just so much and then stop. The next step was creating what would become the first chemical developers, allowing for shorter exposure times and more vivid images printed from his paper negatives.

Various refinements in the “calotype” process followed, along with a hash of bitter patent battles between Talbot and other inventors evolving similar systems. Interestingly, along the way, the need to demonstrate the superior results of his products had the accidental side effect of making Talbot himself one of the period’s most practiced early photographers, giving him equal influence over inventors and artists alike.

In time, Talbot’s calotype system would be further improved by coating glass with collodion, making for a sharper and more detailed negative from which to create prints. The final step toward universal adoption of photography would be George Eastman’s idea for a flexible celluloid-based film negative, the process that ushered in the age of the snapshot and put a camera in Everyman’s hands.

ROOM WITH A VIEW

This 1820’s view from the upper floor of Nicéphore Niépce’s house is generally acknowledged as the first true photograph, revealing rough details of a distant pear tree, a slanted barn roof, and the secondary wing of the estate (at right).

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MANY OF THE MOST IMPORTANT SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERIES ARE ACTUALLY DETOURS, things unearthed by accident in search of something completely different. Marconi was not looking to create the entertainment medium known as radio, but merely a wireless way to send telegraphs. The tough resin known as Bakelite was originally supposed to be a substitute for shellac, since getting the real thing from insects was slow and pricey. Instead, it became the first superstar of the plastics era, used to making everything from light plugs to toy View-Masters.

And the man who, for all practical purposes, invented photography was merely seeking a shortcut for the tracing of drawings.

Nicéphore Niépce, born in France in 1765, plied his trade in the new techniques of lithography, but fell short in his basic abilities as an artist, and searched for a way to get around that shortcoming by technical means. He became proficient in the creation of images with a camera obscura, a light-tight box with a pinhole on one side which projected an inverted picture of whatever it was pointed at on the opposite inside wall of the container, the pinhole acting as a glassless, small-aperture lens. Larger versions of the gadget were used by artists to project a subject onto an area from which tracings of the image could be done, then finished into drawings. Niépce grew impatient with the long lag time involved in the tracing work and began to experiment with various compounds that might chemically react to light, causing the camera’s image to be permanently etched onto a surface, making for a quicker and more accurate reference study.

Niépce tried a combination of fixing chemicals like silver chloride and asphalt, burning faint images onto surfaces ranging from glass to paper to lithographic stone. Some of his earliest attempts registered as negatives, which faded to complete black when observed in sunlight. Others resulted in images which could be used as a master from which to print other images, effectively a primitive kind of photocopy. Finally, having upgraded the quality of his camera obscura and coating a slab of pewter with bitumin, Niépce, around 1827 successfully exposed a permanent, if cloudy image from the window of his country house in La Gras. His account recalled that the exposure took eight hours, but later scientific recreations of the experiment believe it could actually have taken several days. Even at that, Niépce might have recorded a good deal more detail in the image had he waited even longer. In an ironic lesson to all impatient future shooters, the world’s first photograph had, in fact, been under-exposed.

Rather than merely create a short-cut for sketch artists, Nicéphore Niépce’s discovery, which he called heliography (“sun writing”), resulted in a new, distinctly different art that would compete with traditional graphics, forever changing the way painters and non-painters viewed the world. Centuries later, harnessing light in a box is still the task at hand, and the eternally novel miracle of photography.

YOU ARE THE CAMERA

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ON THE DAY I WROTE THIS, the new Hasselblad XI-D-50c medium-format mirrorless camera was announced for pre-order. For the sake of history, it must be recorded here that the introductory price was $9,000.

For the body alone. Lenses (and batteries) not included.

I’m going to let that factoid sink in for a moment, so that you can (a) catch your breath/throw up/faint, or (b) find another blog whose author is impressed by this nonsense.

(Cleansing breath..)

Now, for those who are still with us….

Let me state once more, for the record, that good photography is not defined by either academic training or dazzling hardware. There is no “camera”, in fact, outside yourself. To believe otherwise is to believe that a screwdriver can build a house. Tools are not talent. Moreover, schooling is not a pre-requisite for the creation of art. No one can sell you a camera better than your own brain, and no camera made today (or tomorrow) can save your photography if, like the Scarecrow, you don’t possess one.

I recently read a lament by someone who got his college degree in photography “back when that still meant something”, before the present age, in which, “apparently, everyone’s a photographer”. The sentiment expressed here is that making pictures is the exclusive domain of a few chosen High Priests Of Art, and that all who do not follow the path of the Jedi are, somehow, impure. Pretenders. Usurpers. Monkeys with hand grenades.

This viewpoint, with all its wonderfully elitist flair, was actually rendered obsolete by the introduction of the Kodak Brownie in 1900, since that’s the first time Everyman could pick up and wield a camera without express permission from the Ivy League. Want to see how little it matters how little we know before we hit the shutter? Do your own Google search for the number of world-changing photographers who were self-taught…who, like most of us, simply got better by making lots of bad pictures first. Start with Ansel Adams and work outward.

What does this have to do with Hasselblad’s shiny new Batmobile? Plenty. Because the idea that great images are created by great cameras goes hand-in-snotty-hand with the idea that only the enlightened few can make pictures at all. Never mind the fact that these concepts have been scorned to laughter by the actual history of the medium, as well as its dazzling present. The notion that art is for We, and appreciation is for Thee stubbornly persists, and probably always will. That’s why museum curators get paid more than the artists whose works they hang. Go figure.

But it’s tommyrot.

There is no camera except your own experienced and wise eye. Choose performance over pedigree. You don’t need four years in study hall or a $9.000 Hassie to make a statement. More importantly, if you have nothing to say, merely ponying up for toys and testimonials won’t get you into the club.

EVERYTHING OLD IS….OLD AGAIN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE LOW–HANGING–FRUIT–EASY–LAY–UP STORIES in 2017 pop culture circles was the report that, after years of manufacturing its own version of the defunct Polaroid Corporation’s instant camera film, an appropriately named company known as the Impossible Project had acquired all of Polaroid’s remaining intellectual property. As a result, the IP, now re-born as Polaroid Originals, could now begin making it own brand-new Polaroid cameras.

The story had great appeal for the analog-was-better crowd, the LP-hugging CD haters who pegged the decline of civilization to the day mankind first embraced zeroes and ones. Writer after writer wiped aside a misty tear to rhapsodize about the OneStep2, the first new “Polaroid” camera in more than a decade, and to recount their own fond memories of the “unique” quality of each unreproducable shot, as well as the wonderfully unpredictable randomness of wondering if your next shot, or indeed the entire rest of the film pack, would yield anything in the way of an image that was worth wiping your nose on.

Which brings us to the Brutal Main Truth of the matter: Polaroids were never really good cameras. They were engineered to fulfill a need for uncomplicated and quick gratification, marketed to an audience of snapshooters and selfiemongers. Inventor Edward Land placed all of his emphasis on perfecting the spontaneous function of his film, and to simplifying the taking of pictures to the point that your goldfish could pretty much operate the cameras. That said, Polaroid film was unstable, balky, moody, mushy, and generally useless as an archival medium. Of course, the company tried to shape an alternate narrative: certain high-end, professional grade iterations of the camera appeared at the margins of the photo market, with Polaroid hiring Ansel Adams as a “consultant” on color (which is a little like hiring a childless person to head up a daycare), and the brand got a pass from culture vultures like Andy Warhol, who tried to legitimize the cool, what-the-hell factor of the cameras for a generation hooked on immediacy. But in the end, Polaroid photography delivered mere convenience and fun, seldom art.

In terms of its legacy, there are no classic Polaroid lenses, nor any other evidence that the company ever trusted its customers with taking pictures like grown-ups. Model after model refused to allow users to take even basic manual control of the process of photography, offering instead frozen focal lengths, a stingy array of shutter speeds, and cave-man-level focusing options. Finally, by the dawn of the digital age, Polaroid whimpered out as it had roared in, making the process ever easier, the gear ever cheaper, and the results ever worse.

Polaroid Originals is now poised to do something its namesake never did: make a real good camera for people who also like the tactile, hold-it-in-your-hand sensation of instant photography. But they’re off to a lame start, if the brainless, artless OneStep2 is any indication. Not only is this gob of plastic optically stunted, the film made by Polaroid Originals, who had to figure out the process without any blueprint or guidance from Polaroid, looks even worse than actual Polaroid film, which is a little like finding out that your mud pies don’t look as elegant as everyone else’s. And did we mention the cost, which works out to nearly two dollars per print?

And so, for analog hogs, everything old is really just old again. As we speak, Kodak is preparing to produce an all new Super-8 movie camera… for around $2,400. Surely we can’t be two far from a loving re-launch of the Ford Edsel. I hear they gots a cigarette lighter right in the dashboard…….

Share this:

April 1, 2018 | Categories: Americana, Commentary, History, Intellectual Property | Tags: Instant Photography, Polaroid | Leave a comment