IT TAKES A THIEF

In this composition, people become mere design elements, or props. To get this look, a single exposure was duped, the two images were re-contrasted, and then blended in the HDR program Photomatix for a wider tonal range than in “nature”.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GREAT STREET PHOTOGRAPHERS OF OLD WERE ALL WILY, SLY THIEVES, capturing their prey in emulsion. Yes, I know that the old superstition isn’t literally true. You can’t, in fact, imprison someone’s soul inside that little black box. And yet, in a sense that is very personally felt by many of our subjects today, we are committing an “invasion” of sorts, a kind of artsy assault on the self. Oddly, the same technique that gets you admired when you successfully capture a precious quality of someone else’s face makes you despised when you’re sneaking around to get my picture. Whether street shoots are inspired or reviled is largely a matter of who is being “violated”.

We’ve all heard about Henri Cartier-Bresson, covering the bright chrome trim of his Leica with black electrical tape, the better to keep his camera “invisible” to more of his subjects, as well as the through-the-overcoat candids shot on the New York subway by Walker Evans. And then there is the real risk to personal safety, (including being arrested, jailed, and physically threatened) undertaken by Robert Frank when taking the small-town shots for his legendary street collection, The Americans in the 1950’s. And while most of us aren’t risking incarceration or a punch in the snoot when framing up a stranger, sensitivity has accelerated, as cameras have proliferated into the millions, and personal privacy has, in the digital era, been rendered moot.

Every street shooter must therefore constantly re-negotiate the rules of engagement between himself and the world at large. Is the whole of society his canvas, or is he some kind of media criminal, seeking to advance his own vision at the expense of others’ personhood? I must admit that, at times, I tire of the endless calculation, of the games involved in playing “I’m-here-I’m-not-really-here” with individuals. When my fatigue reaches critical mass, I pull back…..way back, in fact, no longer seeking the stories in individual faces, but framing compositions of largely faceless crowds, basically reducing them to design elements within a larger whole. Malls, streets, festivals…the original context of the crowds’ activities becomes irrelevant, just as the relationship of glass bits in a kaleidoscope is meaningless. In such compositions, the people are rendered into bits, puzzle pieces…things.

And while it’s true that one’s eye can roam around within the frame of such images to “witness” individual stories and dramas, the overall photo can just be light and shapes, arranged agreeably. Using color and tonal modification from processing programs like Photomatix (normally used for HDR tonemapping) renders the people in the shot even more “object-like”, less “subject-like”(see the link below on the “Exposure Fusion” function of Photomatix as well). The resulting look is not unlike studying an ant farm under a magnifying glass, thus a trifle inhuman, but it allows me to distance myself from the process of photostalking individuals, getting some much-needed detachment.

Or maybe I’m kidding myself.

Maybe I just lose my nerve sometimes, needing to avoid one more frosty stare, another challenge from a mall cop, another instance of feeling like a predator rather than an artist. I don’t relish confrontations, and I hate being the source of people’s discomfiture. And, with no eager editors awaiting my next ambush pic of Lindsey Lohan, there isn’t even a profit motive to excuse my intrusions. So what is driving me?

As Yul Brynner says in The King & I, “is a puzzlement.”

(follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye and on Flickr at http://www.flickr.com/photos/mpnormaleye)

Related articles

PICTURES FULL OF PICTURES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FRAME, AS IT HAS BEEN EMPLOYED IN PHOTOGRAPHY, is the visual element that truly sets the terms on which we will engage a picture. The decision of what to include or exclude in the shooter’s specifically defined little universes is the closest one can come to absolute godlike power. Frames enter us into an informal agreement with the photographer, a handshake deal that, yes, we will accept that you are presenting a world bordered by your own vision…whatever its strengths and limits. We enter an image by plunging past the edge of the frame, like the holiday party in Mary Poppins leaping into a sidewalk chalk sketch.

The fun variant in this happens when arrangements of smaller frames arranged within the master frame suggest themselves as a composition that can tell a story all by itself. Odd as it sometimes seems to take “pictures of pictures”, the results can be wonderful, or at least something beyond the mere act of recording. An image showing a wild mass of pinned-up photos of missing persons which is oddly more powerful than a portrait of any one person within it. A wall of randomly sized works within a gallery. A totality of small pictures achieved by merely stepping back, and providing the group with a defining perimeter.

I recently had the good luck to wander into a room within the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) that took me beyond the formal exhibits to a place where a completely new kind of art is constantly being generated. In this room, a children’s art studio, there are no “schools” of painting or “periods” of drawing, just the energetic surge of young minds bursting into productivity on a daily basis. And there, along an entire wall of the workshop, stretched an enormous montage of works of every kind. No themes, no commonalty of conception, just raw, unafraid imagination. The wall, and the two people scanning it (one adult, one child) provided all the story anyone could ever need. The picture took itself.

The frame can frame other frames, and, in doing so, tell very specific truths. It’s a gift when it happens. And there isn’t a photographer alive who doesn’t love a freebie.

(follow Michael Perkins and share your own images on Twitter @mpnormaleye)

FIND THE OUTLIERS

Not the kind of space you’d expect to see in a visually crowded suburban environment. And that’s the point. 1/320 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY TIME MY WIFE AND I TRAVEL, A STRANGE PHENOMENON OCCURS. We will be standing on the exact same geographic coordinates, pointing separate cameras in generally the same general area. And, invariably when she gets her first look at the pictures I took on that day, I will hear the following:

Where was THAT? I don’t remember seeing that!? Where was I?

Of course, we see differently, as do any two shooters. Some things that are blaring red fire alarms to one of us are invisible, below the radar, to the other. And of course we are both right. And valid. Admittedly, I do seem to come back with more strange, off-to-the-side-of-the road oddities than Marian does, but that may be due more to my wildly spasmodic attention span than any real or rare “vision”. Lots of it comes because I consciously trying to overcome the numbing experience of driving in a car. I have to work harder to take notice of the unconventional when repeatedly tracking back and forth,day after day, down routine driving routes. Familiarity not only breeds contempt, it also fosters artificial blindness. The “outliers” within five miles of your own house should glow like fluorescent paint….but often they seem cloaked by a kind of habit-dulled camo.

Once detected, outliers don’t quite fit within their neighboring context. The last Victorian gingerbread home in a clutch of tract houses. The old local movie theatre reborn as a Baptist church. Or, in a place like Phoenix, Arizona, where urban development is not only unbridled but seemingly random, the rare “undeveloped” lot, crammed between more familiar symbols of sprawl.

The above image is such an outlier. It’s about an acre-and-a-half of wild trees bookended by a firehouse,

a row of ranch houses, and a busy four-lane street. Everything else on the block screams “settled turf”, while this strange stretch of twisted trunks looks like it was dropped in from some fairy realm. At least that’s what it says to me.

My first instinct in cases like this is to get out and shoot, attempting, as I go, to place the outlier in its own uncluttered context. Everything else around my “find” must be rendered visually irrelevant, since it adds nothing to the image, and, in fact, can diminish what I’m after. Sometimes I also tweak my own color mix, since natural hues also may not get my idea across.

Even after all this, I often find that there is no real revelation to be had, and I must chalk the entire thing up to practice. Occasionally, I come back with something to show my wife. And I know I have struck gold if the first thing out of her mouth is, “Where is THAT?”

To paraphrase the old proverb, behind every great man is a woman who rightfully asks, “Do you know what you’re doing?”

Sometimes I have an answer….

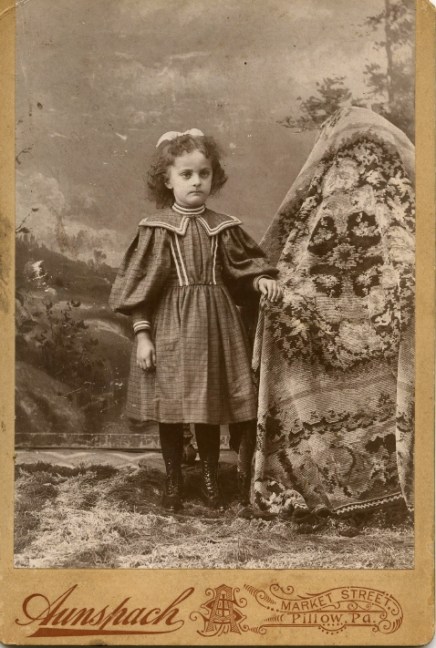

ESCAPE FROM PLANET PORTRAIT

Does this child look happy to you? Does she look like she even has a pulse? Surely we do better kid portraits today, er, don’t we?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TO HEAR US TELL IT, WE ALL REALLY LOVE OUR KIDS. Assuming that to be true, why do we still subject them to the greatest act of photographic cruelty since Tod Browning’s Freaks? I speak of course, of the creatively bankrupt ritual of studio portraits, many of them cranked out at department stores or discount mills, too many of them making our beloved progeny look like waxworks escaped from a casting call for Beetlejuice.

We can surely do better.

I’m on record as believing that children are the noblest work of nature, coming into the world bearing only joy and untainted by the cynical clown olympics that comprise our “adult” way of thinking. And since we all probably feel the same way, why do so many of us park the little dears in front of hideous backdrops, surround them with absurd props, and gussy them up as everything from fairy princesses to ersatz puppies to fake cherubs?

Part of this ridiculous tradition owes its origins to the early days of photography, when a portrait sitting was the one means by which people who might never leave behind any other visual record of their lives were placed in formalized settings for an “official” rendering of their features. Slow film speeds and primitive lighting dictated that parents “leave it to the pros”, giving these modestly gifted artists decades of practice in weaving imaginary dream framings for our precious kids. (Full disclosure: Yes, I know that the image at left is a leftover from the Victorian age. I didn’t post any contemporary images because (a) many of them are almost this bad and you already get the idea, and (b) I wasn’t eager to be beaten to a pulp by any proud parents.)

Could it be more obvious, billions of Instamatics and Instagrams later, that this sad ritual hasn’t had any fresh air pumped into it since the golden age of Olan Mills class pictures? Even the most elementary “how-to” books on candid photography have been telling us the same thing for nearly a century: don’t formalize the setting, formalize your thinking. Let your child show you what he is, in his own environment. That means that you need to shoot constantly and invisibly, getting out of the kid’s way. No 3-2-1 “Cheese!” commands, no “sit up straight and don’t slouch” advice, no arbitrary situation.

Sure, you can basically plan how you will shoot your child, but allow him to unfold before your ready camera and gain the confidence to react in the moment. Stop trying to herd him into a structure or a setting. If at all possible, allow him to forget that you’re even in the room. Witness something wonderful instead of trying to construct it. Be a fly on the wall. The child is pitching great stuff every time he’s on the mound. Just make sure you’re behind the plate to to catch it.

Dirty little secret: there is nothing “magical” about most studio portraits. In fact, many of the results from the photo mills are just about the most un-magical pictures ever taken, although there are signs that things are changing. It simply isn’t enough to ensure a perfectly diffused background and an electronically exact flash. Even today’s most humble personal cameras have amazing flexibility to capture flattering light and isolate your subject from distracting backgrounds. And going from standard “kit” lenses (say, an 18-55mm) to an affordable prime lens (35mm, 50mm) gives us insane additional gobs of light to work with, all without using the dreaded pop-up flash, the photographic equivalent of child abuse.

Doing it yourself with kid portraits is work, make no mistake. You have to be flexible. You have to be fearless. And you have to know when something magical’s about to happen. But it’s your child, and there is no outside contractor who has a better sense of what delight he has inside him.

Besides, isn’t it likelier that he will show you the magic in his own back yard than in a back room at K-Mart? Give him something that he loves to do, the better to forget you’re there, and crank away. I mean shoot a lot. And don’t stop.

You’re the expert here.

Don’t outsource your joy.

STRING THEORY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CERTAIN INANIMATE OBJECTS INTERACT WITH THE LIVING TO SUCH A LARGE DEGREE, that, to me, they retain a certain store of energy

even when standing alone. Things that act in the “co-creation” of events or art somehow radiate the echo of the persons who touched them.

Musical instruments, for my mind’s eye, fairly glow with this force, and, as such, are irresistable as still life subjects, since, literally, there is still life emanating from them.

Staging the object just outside the reach of full light helped the violin sort of sculpt itself. 1/800 sec., f/2.5, ISO 100, 35mm prime lens.

A while back I learned that my wife had, for years, held onto a violin once used for the instruction of one of her children. I was eager to examine and photograph it, not because it represented any kind of technical challenge, but because there were so many choices of things to look at in its contours and details. There are many “sites” along various parts of a violin where creation surges forth, and I was eager to see what my choices would look like. Also, given the golden color of the wood, I knew that one of our house’s “super windows”, which admit midday light that is soft and diffused, would lend a warmth to the violin that flash or constant lighting could never do.

Everything in the shoot was done with an f/1.8 35mm prime lens, which is fast enough to illuminate details in mixed light and allows for selectively shallow depth of field where I felt it was useful. Therefore I could shoot in full window light, or, as in the image on the left, pull the violin partly into shadow to force attention on select details.

Although in the topmost image I indulged the regular urge to “tell a story” with a few arbitrary

props, I was eventually more satisfied with close-ups around the body of the violin itself, and, in one case, on the bow. Sometimes you get more by going for less.

One thing is certain: some objects can be captured in a single frame, while others kind of tumble over in your mind, inviting you to revisit, re-imagine, or more widely apprehend everything they have to give the camera. In the case of musical instruments, I find myself returning to the scene of the crime again and again.

They are singing their songs to me, and perhaps over time, I quiet my mind enough to hear them.

And perhaps learn them.

SKIN IN THE GAME

“Old Faithful”, the jacket that has accompanied me on more shoots than any other single piece of “gear”. 1/200 sec., f/2.8, ISO 100, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE ONE PIECE OF “EQUIPMENT” THAT HAS SEEN ME THROUGH THE TRANSITION FROM FILM TO DIGITAL is not a hunk of techno gear. In fact, it has not directly figured in the taking of even a single picture. I was reminded of its amazing longevity a few months ago, as I was going through a 2002 shoot done in Ireland. Among my own shots was a pretty good candid of me, taken by my wife, as I crouched to line up a shot next to a road heading to the Ring of Kerry. And there “it” was with me.

In fact, it was keeping me warm and dry.

Context: I never took the plunge of the eager amateur and purchased one of those puffy, sleeveless photog vests, honeycombed with a zillion pockets, pouches and secret compartments, much as I never painted the words CAMERA NERD on my face in day-glo orange. Chalk it up to self-consciousness. I figured it was hard enough to blend in and keep people relaxed in a shooting situation without looking like a cross between a spinster butterfly hunter and a middle-school lab assistant. Call me vain.

And you’d be right.

So, a plain brown leather jacket. Gimme three good pockets and call it day. And thus it was that, for the next thirteen years or so, I have had “skin in the game”, skin that has survived exploded pens, leaked batteries, rotten weather on two sides of the Atlantic, and more scrapes, tears, and rips than I care to recall. It has also helped keep countless camera straps from inscribing a permanent groove in my left shoulder, and, here in the Land Of Incipient Arthritis, I appreciate that more than I can say.

Such service calls for a little respect, and so, in the name of the weirdest still lifes ever, I figured it was time for Old Faithful to pose for a portrait of its own. Originally I thought to lay it out straight, the way they show off famous duds at the Smithsonian. But what really caught my eye was that, texture-wise, it is almost six different jackets, from the glossy sheen of an old horse saddle to the frayed look of something that’s been making out with a cheese grater.

At the last, I simply experimented with a few crumpled waves of grain, as if the jacket had been hastily tossed aside, which, trust me, it has been, on countless occasions.

Best thing is, when I’m ready, it’s still there.

I’m not a big fan of good luck charms, but maybe some things protect against bad luck, and that’s no easy feat, either. Either way, me and what Kipling would have called my “Lazarushian leather” and I will keep signing up new missions.

At least until one of our arms fall off.

LET THERE BE (MORE) LIGHT

A new piece of glass makes everything look better….even another piece of glass. First day with my new 35mm prime lens, wide open at f/1.8, 1/160 sec., ISO 100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE RECENTLY BEEN EXPERIENCING ONE OF THOSE TIME MACHINE MOMENTS in which I am, again, right back at the beginning of my life as a photographer, aglow with enthusiasm, ripe with innocence, suffused by a feeling that anything can be done with my little black box. This is an intoxication that I call: new lens.

Without fail, every fresh hunk of glass I have ever purchased has produced the same giddy wonder, the same feeling of artistic invincibility. This time out, the toy in question is a Nikon f/1.8 35mm prime lens, and, boy howdy, does this baby perform. For cropped sensor cameras, it “sees” about like the 50mms of old, so its view is almost exactly as the human eye sees, without exaggerated perspective or angular distortion. Like the 50, it is simple, fast, and sharp. Unlike the 50, it doesn’t force me to do as much backing up to get a comfortable framing on people or near objects. The 35 feels a little “roomier”, as if there are a few extra inches of breathing space around my portrait subjects. Also, the focal field of view, even wide open, is fairly wide, so I can get most of your face tack sharp, instead of just an eye and a half. Matter of preference.

All this has made me marvel anew at how fast many of us are generally approaching the age of flashless photography. It’s been a long journey, but soon, outside the realm of formal studio work, where light needs to be deliberately boosted or manipulated, increasingly thirsty lenses and sensors will make available light our willing slave to a greater degree than ever before. For me, a person who believes that flash can create as many problems as it solves, and that it nearly always amounts to a compromise of what I see in my mind, that is good news indeed.

It also makes me think of the first technical efforts to illuminate the dark, such as the camera you see off to the left. The Ermanox, introduced by the German manufacturer Ernemann in 1924, was one of the first big steps in the quest to free humankind of the bulk, unreliability and outright danger of early flash. Its cigarette-pack-sized body was dwarfed by its enormous lens, which, with a focal length of f/2, was speedy enough (1/1000 max shutter) to allow sharp, fast photography in nearly any light. It lost a few points for still being based on the use of (small) glass plates instead of roll film, but it almost single-handedly turned the average man into a stealth shooter, in that you didn’t have to pop in hefting a lotta luggage, as if to scream “HEY, THE PHOTOGRAPHER IS HERE!!” In fact, in the ’20’s and ’30’s, the brilliant amateur shooter Erich Solomon made something of a specialty out of sneaking himself and his tiny Ermanox into high-level government summits and snapping the inner circle at its unguarded best (or worst). Long exposures and blinding flash powders were no longer part of the equation. Candid photography had crawled out of its high chair… and onto the street.

Today or yesterday, this is about more than just technical advancement. The unspoken classism of photography has always been: people with money get great cameras; people without money can make do. Sure, early breakthroughs like the Ermanox made it possible for anyone to take great low-light shots, but at $190.65 in 1920’s dollars, it wasn’t going to be used at most folks’ family picnics. Now, however, that is changing. The walls between “high end” and “entry level” are dissolving. More technical democracy is creeping into the marketplace everyday, and being able to harness available light affordably is a big part of leveling the playing field.

So, lots more of us can feel like a kid with a new toy, er, lens.

Related articles

- Prime Lenses (nikonusa.com)

- Understanding Focal Length (nikonusa.com)

THE OTHER 50%

By MICHAEL PERKINS

The American Dream, Pacific Grove, California, 2012. A three-exposure HDR with shutter speeds ranging from 1/100 to 1/160, all three shots at f/8, ISO 100, 32mm.

THE LAST SUNDAY EDITION OF THE NEW YORK TIMES FOR 2012 features its annual review of the year’s most essential news images, a parade of glory, challenge, misery and deliverance that in some ways shows all the colors of the human struggle. Plenty of material to choose from, given the planet’s proud display of fury in Hurricane Sandy, the full scope of evil on display in Syria, and the mad marathon of American politics in an electoral year. But photography is only half about recording, or framing, history. The other half of the equation is always about creating worlds as well as commenting on them, on generating something true that doesn’t originate in a battlefield or legislative chamber. That deserves a year-end tribute of its own, and we all have images in our own files that fulfill the other 50% of photography’s promise.

This year, for example, we saw a certain soulfulness, even artistry, breathed into Instagram and, by extension, all mobile app imaging. Time ran a front cover image of Sandy’s ravages taken from a pool of Instagramers, in what was both a great reportorial photo and an interpretive shot whose impact goes far beyond the limits of a news event. Time and again this year, I saw still lifes, candids, whimsical dreams and general wonderments of the most personal type flooding the social media with shots that, suddenly, weren’t just snaps of the sandwich you had for lunch today saturated with fun filters. It was a very strong year for something personal, for the generation of complete other worlds within a frame.

I love broad vistas and sweeping visual themes so much that I have to struggle constantly to re-anchor myself to smaller things, closer things, things that aren’t just scenic postcards on steroids, although that will always be a strong draw for me. Perhaps you have experienced the same pull on yourself…that feeling that, whatever you are shooting, you need to remember to also shoot…..something else. It is that reminder that, in addition to recording, we are also re-ordering our spaces, assembling a custom selection of visual elements within the frame. Our vision. Our version. Our “other 50%.”

My wife and I crammed an unusual amount of travel into 2012, providing me with no dearth of “big game” to capture…from bridges and skyscrapers to the breathlessly vast arrays of nature. But always I need to snap back to center….to learn to address the beauty of detail, the allure of little composed universes. Those are the images I agonize over the most at years’ end, as if I am poring over thumbnails to see a little piece of myself , not just in the mountains and broad vistas, but also in the grains of sand, the drops of dew, the minutes within the hours.

Year-end reviews are, truly, about the big stories. But in photography, we are uniquely able to tell the little ones as well. And how well we tell them is how well we mark that we were here, not just as observers, but as participants.

It’s not so much how well you play the game, but that you play.

Happy New Year, and many thanks for your attention, commentary, and courtesy in 2012.

Related articles

- 10 social mobile photography trends for 2013 (davidsmcnamara.typepad.com)

- Old-Timer Joins Instagram, Schools Everyone With Poignant Flood Photos (wired.com)

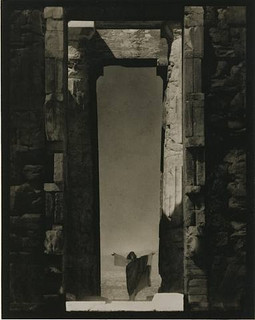

I SEE YOUR FACE BEFORE ME

Edward Steichen’s amazing 1921 portrait of dance icon Isadora Duncan beneath a massive arch of the Parthenon in Greece, an image which recently surged to the top of my mind. See a link to a larger view of this shot, below.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE IMAGES SIT AT THE BOTTOM OF THE BRAIN, LIKE STONE PILLARS IN THE FOUNDATION OF AN IMMENSE TOWER.The structures erected on top of them, those images we ourselves have fashioned in memory of these foundations, dictate the height and breadth of our own creative edifices. Between these elemental pictures and what we build on top of them, we derive a visual style of our own.

In my own case,many of the pillars that hold up my own house of photography come from a single man.

Edward Steichen is arguably the greatest photographer in history. If that seems like hyperbole, I would humbly suggest that you take a reasonable period of time, say, oh, twenty years or so, just to lightly skim the breadth of his amazing career….from revealing portraits to iconic product shots to nature photography to street journalism and half a dozen other key areas that comprise our collective craft of light writing. His work spans the distance from wet glass plates to color film, from the Edwardian era to the 1960’s, from photography as an insecure imitation of painting to its arrival as a distinct and unique art form in its own right.

At the start of the 20th century, Steichen co-sponsored many of the world’s first formal photographic galleries, and was a major contributor to Camera Work, the first serious magazine dedicated wholly to photography. He ended his career as the creator of the legendary Family Of Man, created in the early 1950’s and still the most celebrated collection of global images ever mounted anywhere on earth. He is, simply, the Moses of photography, towering above many lesser giants whose best work amounts to only a fraction of his own prodigious output.

Which is why I sometimes see fragments of what he saw when I view a subject. I can’t see with his clarity, but through the milky lens of my own vision I sometime detect a flashing speck of what he knew on a much larger scale, decades before. The image at left recently rocketed to my mind’s eye several weeks ago, as I was framing shots inside a large government building in Ohio.In 1921, Steichen journeyed to Greece to use the world’s oldest civilization basically as a prop for portraits of Isadora Duncan, then in the forefront of American avant-garde dance. Framing her at the bottom of an immense arch in the ruins of the Parthenon, he made her appear majestic and minute at the same time, both minimized and deified by the huge proportions in the frame. It is one of the most beautiful compositions I have ever seen, and I urge you to click the Flickr link at the end of this post for a slightly larger view of it. (Also note the link to a great overview of Steichen’s life on Wikipedia.)

Uplighting creates a moody frame-within-frame feel at the Ohio Statehouse building, in a shot inspired by Edward Steichen’s images of massive arches. 1/30 sec., f/8, ISO 800, 18mm.

In framing a similarly tall arch leading into the rotunda of the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, I didn’t have a human figure to work with, but I wanted to show the building as a series of major and minor access cavities, in, around, under and through one of its arched entrance to the central lobby. I kept having to back up and step down to get at least a partial view of the rotunda and the arch at the opposite end of the open space included in the frame, which created a kind of left and right bracket for the shot, now flanked by a pair of staircases. Given the overcast sky meekly leaking grey light into the rotunda’s glass cupola, most of the building was shrouded in shadow, so a handheld shot with sufficient depth of field was going to call for jacked-up ISO, and the attendant grungy texture that remains in the darker parts of the shot. But at least I walked away with something.

What kind of something? There is no”object” to the image, no story being told, and sadly, no dancing muse to immortalize. Just an arrangement of color and shape that hit me in some kind of emotional way. That and Steichen, that foundational pillar, calling up to me from the basement:

“Just take the shot.”

Related articles

- The Photograph as a Social Statement (halsmith.wordpress.com)

- Picture Imperfect (andrewsullivan.thedailybeast.com)

- http://www.flickr.com/photos/quelitab/5793648357/lightbox/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Steichen

THE PROSCENIUM

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT IS THE OLDEST FRAMING DEVICE IN HISTORY. If you’ve ever watched a play on any stage, anywhere in the world, you’ve accepted it as the classic method of visual presentation. The Romans coined the word proscenium, “in front of the scenery”. Between stage left and stage right exists a separate reality, defined and contained in the finite space of the theatre’s forward area. What is included in the frame is everything, the center of the universe of certain characters and events. What’s outside the frame is, indefinite, vague, less real.

Just like photography, right? Or to be accurate, photography is like the proscenium. We, too select a specific world to display. We leave out all the other worlds not pertinent to our message. And we follow information in linear fashion…left to right, right to left. The frame gives us the sensation of “looking in” to something that we are only visiting, just as we only “rent” our viewpoint from our theatre seats.

We learned our linear habit from the descendants of stage arrangement….murals, frescoes, paintings, all working, as our first literate selves would, from left to right. Painters were forced to arrange information inside the frame, to make choices of what that frame would include, and, as the quasi-legitimate children of painting, we inherited that deliberately chosen viewpoint, that decision to show a select world, by arranging visual elements within the frame.

Park Slope, Brooklyn, 2012. Trying to catch as much activity as a street glance, at any given moment, can. 1/320 sec., F/7.1, ISO 100, 24mm.

For some reason, in recent months, I have been abandoning the non-traditional in shooting street scenes and harking back to the proscenium, trying to convey a contained world of simple, direct left-right information. Candid neighborhood shots seem to work well without extra adornment. Just pick your borders and make your capture. It’s a way of admitting that some worlds come complete just as they are. Just wrap the frame around them like a packing crate and serve ’em up.

Like a theatre play, some images read best as self-contained, left-to-right “worlds”. A firehouse in Brooklyn, 2012. 1/60 sec., f/6.3, ISO 100, 38mm.

This is not to say that an angled or isometric view can’t portray drama or reality as well as a “stagy” one. Hey, sometimes you want a racing bike and sometimes you want a beach cruiser. Sometimes I don’t mind that the technique for getting a shot is, itself, a little more noticeable. And sometimes I like to pretend that there really isn’t a camera.

That’s theatre. You shouldn’t believe that the well-meaning director of the local production of Oklahoma really conjured a corn field inside a theatre. But you kind of do.

Hey what does Picasso say? “Art is the lie that tells the truth”?

Okay, now I’m making my own head hurt. I’m gonna go lie down.