DARKNESS AS SCULPTOR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN DAYLIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY, THE DEFAULT ACTION TENDS TO BE TO SHOW EVERYTHING. Shadows in day scenes are a kind of negative reference to the illuminated objects in the frame, but it is those objects, and not the darkness, that defines space. In this way shady areas are a kind of decor, an aid to recognition of scale and depth.

At night, however, the darkness truly plays a defining role, reversing its daylight relationship to light. Dark becomes the stuff that night photos are sculpted from, creating areas that can remain undefined or concealed, giving images a sense of understatement, even mystery. Not only does this create compelling compositions of things that are less than fascinating in the daytime, it allows you to play “light director” to selectively decide how much information is provided to the viewer. In some ways, it is a more pro-active way of making a picture.

This bike shop took on drastically different qualities as the sun set. 1/40 sec., f/3.5, ISO 100, 18mm.

I strongly recommend walkabout shoots that span the complete transition from dusk to post-sunset to absolute night. Not only will the quickly changing quality of light force you to make decisions very much in-the-moment, it allows for a vast variance in the visual power of your subjects that is starkly easy to measure. It’s a great practice lab for shooting completely on manual, and, depending on the speed of your chosen lens (and greater ISO flexibility in recent cameras), makes relatively noise -free, stable handheld shots possible that were unthinkable just a few years ago. One British writer I follow recently remarked, concerning ISO, that “1600 is the new 400”, and he’s very nearly right.

So wander around in the dark. The variable results force you to shoot a lot, rethink a lot, and experiment a lot. Even one evening can accelerate your learning curve by weeks. And when darkness is the primary sculptor of a shot, lovely things (wait for the bad pun) can come to light (sorry).

STOP AT “YES”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE SEEMS TO BE A PROPENSITY, WITHIN THE DNA OF EVERY PHOTOGRAPHER, to “show it all”, to flood the frame with as much visual information as humanly possible in an attempt to faithfully render a story. Some of this may track back to the first days of the art, when the world was a vast, unexplored panorama, a wilderness to be mapped and recorded. Early shutterbugs risked their fortunes and their lives to document immense vistas, mountain ranges, raging cataracts, daunting cliffs. There was a continent to conquer, an immense openness to capture. The objectives were big, and the resultant pictures were epic in scale.

Seemingly, intimacy, the ability to select things, to zero in on small stories, came later. And for some of us, it never comes. Accordingly, the world is flooded with pictures that talk too loudly and too much, including, strangely, subjects shot at fairly close range. The urge is strong to gather, rather than edit, to include rather than to pare away. But there are times when you’re just trying to get the picture to “yes”, the point at which nothing else is required to get the image right, which is also the point at which, if something extra is added, the impact of the image is actually diminished. I, especially, have had to labor long and hard to just get to “yes”….and stop.

In the above image, there are only two elements that matter: the border of brightly lit paper lanterns at the edge of a Chinese New Year festival and the small pond that reflects back that light. If I were to exhaust myself trying to also extract more detail from the surrounding grounds or the fence, I would accomplish nothing further in the making of the picture. As a matter of fact, adding even one more piece of information can only lessen the force of the composition. I mention this because I can definitely recall occasions when I would whack away at the problem, perhaps with a longer exposure, to show everything in more or less equal illumination. And I would have been wrong.

Even with this picture, I had to make myself accept that a picture I like this much required so little sweat. Less can actually be more, but we have to learn to get out of our own way….to stop at “yes”.

THE OLD, DARK HOUSE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE ULTIMATE ADAGE ABOUT OLD HOUSES, I.E.,”THEY SURE DON’T MAKE ‘EM LIKE THIS ANYMORE“, is a sentiment which will haunt the casual photographer at every turn inside an historic home. No, they don’t make them anything like this anymore, especially when it comes to the size of rooms, angles of design, decorative materials, or light flow, and so shooting an antique residence requires a little re-fitting of the brain to insure that you come home with something that you can, you know, bear to look at.

Another cliché that comes to mind, this one about size: “the kitchen was so small, you had to go outside to chew.” Again, it can’t become a cliché unless it’s partially true, and it does apply to many of the rooms in pre-1950’s houses. People were shorter. The concept of personal space, especially in an urban setting, seems claustrophobic to us today. That makes for photos that will also look cramped and tight, so shoot with as wide a lens as you can. This is the place for that 18-55mm kit lens you got with your camera, since it will slightly exaggerate the side-to-side and front-to-back distances within the smaller rooms. It will also allow you to get more in the frame when composing at shorter distances, which, on velvet rope tours, can be reduced to inches.

One crucial thing to be mindful of is that 90% of the light you get on old house tours will be window light. Highlights will almost certainly be blown out on things like sheer drapes, but you need all the light you can get, since it’s a cinch that flash will be prohibited and the interior wood trims, floors and furnishings will likely be very dark in themselves, acting as light blotters. Learn to live with the extreme contrasts and resulting shadowy areas. Expose for the most important elements in a room. You cannot show everything to perfect advantage. In some interior rooms in older homes, you don’t have a shot at all, unless you ditch the rest of the tour group and have about twenty minutes to yourself to set things up. Unlikely.

A wide-angle lens helps to open up shallow spaces with an enhanced sensation of depth. 1/50 sec., f/3.5, ISO 800, 18mm.

If you are shooting with a wide-angle, you may not be able to go any further open on aperture than about f/3.5. This means either working rock-solid handheld or cranking up the old ISO. If you do the latter, don’t go back later with an editor and try to rescue the darker areas: you will just show the smudgy noise that you allowed with the higher ISO, so, unless you like the warm look of black mayonnaise, resist.

Again, if shooting wide, remember that you can also zoom in tight enough to isolate clusters of items in charming still life arrangements with basically no effort on your part. Hey, an expert has already been paid to professionally build your composition for you with period bric-a-brac, so it’s easy pickings, right?

Admittedly, shooting in an old house can be like trying to conduct a prize fight inside a shoe box.

Or it can be like coming home.

THREE STEPS TO SOFT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“But soft! What light through yonder window breaks…?” —Shakespeare

LIGHT IS A RAW RESOURCE, MUCH LIKE IRON ORE OR GOLD NUGGETS. It needs to be refined, alloyed for it to truly be a tool in picture making. For the purpose of photography, what we call “available” light means just that; it’s there, but not in its final form. Making images means becoming an active shaper of light–bouncing it, boosting it, adding or subtracting bits of it, harnessing it if you will. Turning “available” light into usable light is the true alchemy of photography.

That doesn’t mean you can’t benefit greatly from accidents.

The above image was the result of pure seat-of-the-pants whimsy, a momentary impulse to try an idea just to see what happens. However, it was a lucky reworking of available light that drew me to the location before the idea took shape.

I have written volumes on how very harsh the pure midday sunlight is in Arizona, and how it can only be of use if it is filtered or softened in some way. To that end, I have identified various sites around my house which get that done beautifully, depending on where the sun is in the sky during different parts of the day. Some of these sites occur just inside the garage, in the living room, and in a spare bedroom, and shoots will work wonderfully depending on when and where you schedule them. Best of all, the house apparently still holds a few more surprises.

Several days ago, I discovered a new and most unusual site…..a dense art window just to the left of our master bathroom shower stall, which turns out to be a triple softener for late afternoon light, just pre-golden hour. As light streams through the window, it gets softened for the first time, then hits the mirrored closet doors on the opposite wall, where it diffuses some more. Bouncing off the mirror, it then angle-bounces to the back wall of the shower stall, still fairly bright but now really fuzzed out and warm. And that’s where I saw it, as I was walking through the room.

As soon as I spotted the light, I started brainstorming about what kind of object I might stage in this little “studio”, and I hit on the idea of a ukulele, since I always have scads of them around the house, they’re colorful, and it’s kind of an absurd variation on the whole “singing in the shower” cliche. I liked the shot from a purely light effect standpoint, and the unique shaping of the glow in that space will definitely be back for a return engagement.

Maybe a saxophone….

ONE OUT OF FOUR

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF YOU ARE DEPENDENT ON NATURAL LIGHT FOR YOUR ONLY SOURCE OF ILLUMINATION IN AN IMAGE, you have to take what nature and luck afford you. Making a photograph with what’s available requires flexibility, patience, and, let’s face it, a sizable amount of luck. It means waiting for your moment, hell, maybe your instant of opportunity, and it also means being able to decide quickly that now is the time (perhaps the only time) to press the button.

I recently had such a situation, measured in the space of several seconds in which the light was ready and adequate for a shot. And, as usual, the subject seemed as if it would serve up anything but acceptable conditions. The main bar of the classic western “joint” named Greasewood Flats, just outside of northern Scottsdale, Arizona, is anything but ideal in its supply of available light. Most of the room is a tomb, where customers become blobby silhouettes and fixtures and features are largely cloaked in shadow. I had squeezed off a few shots of customers queued up for bar orders, and they all registered as shifting shadows. The shots were unworkable, and I turned my attention to the fake-cowboy-ersatz-dude-ranch flavor of the grounds outside the bar, figuring that the hunt inside would be fruitless.

Minutes later, I was sent back inside the building to fetch a napkin, and found the bar empty of customers. I’m talking no human presence whatever. In an instant, I realized that the outside window light, which was inadequate to fill a four-sided, three-dimensional space, was perfectly adequate as it spread along just one wall. With crowds out of the way, the rustic detail that made the place charming was suddenly a big still-life, and the whole of that single wall was suddenly a picture. My earlier shots were too constrasty at f/5.6, so I tried f/3.5 and picked up just enough detail to fill the frame with Old West flavor. Click.

All natural light is a gift, but it does what it wants to do, and, to harness it for a successful shot, you need to talk nice, wait your turn, and remember to give thanks. And, in a dark room, be happy with one wall out of four that wants to work with you.

MORE BOUNCE TO THE OUNCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR THE MOST PART, THE USE OF ON-CAMERA FLASH SHOULD BE CONSIDERED A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY. Scott Kelby, the world’s best-selling author of digital photography tutorials, famously remarked that “if you have a grudge against someone, shoot them with your pop-up flash, and it will even the score.” But, to be fair, let’s look at the pros and cons of using on-board illumination:

PROS : Cheap, handy

CONS: Harsh, Weak, Unflattering, Progenitor of Red-eye. Also, Satan kills a puppy every time you use it. Just sayin’.

There are, however, those very occasional situations where supplying a little bit of extra light might give you just the fill you need on a shot that is getting 90% of its light naturally. Even so, you have to employ trickery to harness this cruel blast of ouch-white, and simple bounces are the best way to get at least some of what you want.

In the above situation, I was shooting in a hall fairly flooded with bright mid-morning light, which was extremely hot on the objects it hit squarely but contrasty as an abandoned cave on anything out of its direct path. The fish sculpture in my proposed shot was getting its nose torched pretty good, but in black and white, the remainder of its body fell off sharply, almost to invisibility. I wanted the fish’s entire body in the shot, the better to give a sense of depth to the finished picture, but I obviously couldn’t flash directly into the shelf that overhung it without drenching the rest of the scene in superfluous blow-out. I needed a tiny, attenuated, and cheap fix.

Bending a simple white stationery envelope into a “L”, I popped up my camera’s flash and covered the unit with the corner of the envelope where the two planes intersected. The flash was scooped up by the envelope, then channeled over my shoulder, blowing onto the wall at my back, then bouncing back toward the fish in softened condition near the underside of the shelf, allowing just enough light to allow the figure’s bright nose to taper back gradually into shadow, revealing additional texture, but not over-illuminating the area. It took about five tries to get the thing to look as if the light could have broken that way naturally. Fast, cheap, effective.

The same principle can be done, with some twisting about, to give you a side or ceiling bounce, although, if high reflectivity is not crucial, I frankly recommend using your hand instead of the envelope, since you can twist it around with greater control and achieve a variety of effects.

Of course, the goal with rerouting light is to look as if you did nothing at all, so if you do save a picture with any of these moves, keep it to yourself. Oh, yes, you say modestly, that’s just the look I was going for.

Even as you’re thinking, whew, fooled ’em again.

THE PARTY’S OVER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS THE SCIENCE OF SECONDS. The seconds when the light plays past you. The seconds when the joy explodes. The seconds when maybe the building explodes, or the plane crashes. The micro moments of emotion’s arrivals and departures. Here it comes. There it goes. Click.

We are very good with the comings….the beginnings of babies, the opening of a rose, the blooming of a surprised smile. However, as chroniclers of effect, we often forget to also document the goings of life. The ends of things. The moment when the party’s over.

Christmas is a time of supreme comings and goings, and we have more than a month of ramp-up time each year during which we snap away at what is on the way. The gatherings and the gifts. The approaching joy. But a holiday this big leaves echoes and vacuums when it goes away, and those goings are photo opportunities as well.

This year, on 12/26, the predictably melancholy “morning after” found me driving around completely without pattern or design, looking for something of the magic day that had departed. I spun past the abandoned ruin of one of those temporary Christmas tree lots that sprout in the crevices of every city like gypsy camps for about three weeks out of the year, and something about all its emptiness said picture to me, so I got out and started bargaining with a makeshift cyclone fence for a view of the poles, lights and unloved fir branches left behind.

The earliness of the hour meant that the light was a little warmer and kinder than would be the case later on in the bleached-out white of an Arizona midday, so the scene was about as nice as it was going to get. But what I was really after was the energy that goes out of things the day the circus drives out of town. The holidays are ripe with that feeling of loss, and, to me, it’s at least as interesting as recording the joy. Without a little tragedy you don’t appreciate triumph, and all that. Christmas trees are just such an obvious measure of that flow: one day you’re selling magic by the foot, the next day you’re packing up trash and trailer and making your exit.

Photographs come when they come, and, unlike us, they aren’t particular about what their message is. They just present chances to see.

Precious chances, as it turns out.

EAVESDROPPING ON REALITY

Stepping onto Blenkner Street and into history. Columbus, Ohio’s wonderful German Village district, December 2013. 1/60 sec., f/1.8, ISO 800, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE FAMILIAR ADMONITION FROM THE HIPPOCRATIC OATH, the exhortation for doctors to, “First, Do No Harm” has applications to many kinds of enterprises beyond the scope of medicine, photography among them. We are so used to editing, arranging, scouting, rehearsing and re-imagining reality that sometimes, we need merely to eavesdrop on it.

Some pictures are so complete in themselves that, indeed, even minimal interference from a photographer is a bridge too far. Sometimes such images come as welcome relief after a long, unproductive spell of trying to force subjects into our cameras, only to have them wriggle away like so much conceptual smoke. I recently underwent several successive days of such frustration in, of all things, my own home town, fighting quirky weather, blocked access, and a blank wall of my own mental making. I finally found something I can use in (say it all together) the last place I was looking.

In fact, it was a place I hadn’t wanted to be at all.

Columbus, Ohio at night in winter is lots of things, but it’s seldom conducive to any urge more adventurous than reheating the Irish coffee and throwing another log on the fire. At my age, there’s something about winter and going out after sunset that screams “bad idea” to me, and I was reluctant to accept a dinner invite that actually involved my schlepping across the tundra from the outskirts to the heart of downtown. Finally, it was the lure of lox and bagel at Katzinger’s deli, not my artistic wanderlust, that wrenched me loose from hearth and home, and into range of some lovely picture-making territory.

The German Village neighborhood, along the city’s southern edge, has, for over a century, remained one of the most completely intact caches of ethnic architecture in central Ohio, its twisty brick streets evoking a mini-Deutschland from a simpler time. Its antique street lamps, shuttered windows and bricked-in gartens have been an arts and party destination for generations of visitors, casting its spell on me clear back in high school. Arriving early for my trek to Katzie’s, I took advantage of the extra ten minutes to wander down a few familiar old streets, hoping they could provide something….unfamiliar.

The recently melted snowfall of several days prior still lent a warm glaze to the cobbled alleyways, and I soon found myself with city scenes that evoked a wonderful mood with absolutely minimal effort. The light was minimal as well, often coming from just one orange sodium-vapor street lamp, and it made sense to make them the central focus of any shots I was to take, allowing the eye to be led naturally from the illuminated streets at the front of the frame clear on back to the light’s source.

Using my default lens, a 35mm prime at maximum f/1.8 aperture, and an acceptable amount of noise at ISO 800, I clicked away like mad, shooting up and down Blenkner Street, first toward Third Street, then back around toward High. I didn’t try to rescue the details in the shadows, but let the city more or less do its own lighting with the old streets. I capped my lens, stole away like the lucky thief I had become, and headed for dinner.

The lox was great, too. Historic, in fact.

CHANGE OF PLAN

Rainy day, dream away. Griffith Observatory under early overcast, 11/29/13. 1/160, f/5.6, ISO 100, 35mm.

by MICHAEL PERKINS

VISUAL WONDERS, IN EVERY HOUR AND SEASON, ARE THE COMMON CURRENCY OF CALIFORNIA’S GRIFFITH OBSERVATORY. The setting for this marvelous facility, a breathtaking overlook of downtown Los Angeles, the Hollywood Hills, and the Pacific Ocean, will evoke a gasp from the most jaded traveler, and can frequently upstage the scientific wonders contained within its gleaming white Deco skin.

And when the light above the site’s vast expanse of sky fully asserts itself, that, photographically, trumps everything. For, at that moment, it doesn’t matter what you originally came to capture.

You’re going to want to be all about that light.

Upon my most recent visit to Griffith, the sky was dulled by a thick overcast and drenched by a slate-grey rain that had steadily dripped over the site since dawn. The walkways and common decks were nearly deserted throughout the day, chasing the park’s visitors inside since the opening of doors at noon. By around 3pm, a slow shift began, with stray shafts of sun beginning to seek fissures in the weakening cloud cover. Minute by minute, the dull puddles outside the telescope housing began to gleam; shadows tried to assert themselves beneath the umbrellas ringing the exterior of the cafeteria; the letters on the Hollywood sign started to warm like white embers; and people of all ages ventured slowly to the outside walkways.

The moment the light broke, Griffith’s common areas after the rain,11/29/13. 1/640 sec., f/5.6 (this image), f/6.3 (lower image), ISO 100, 35mm.

By just after 5 in the afternoon, the pattern had moved into a new category altogether. As the overcast began to break and scatter, creating one diffuser of the remaining sunlight, the fading day applied its own atmospheric softening. The combination of these two filtrations created an electric glow of light that flickered between white hot and warm, bathing the surrounding hillsides with explosive pastels and sharp contrasts. For photographers along the park site, the light had undoubtably become THE STORY. Yes the buildings are pretty, yes the view is marvelous. But look what the light is doing.

Like everyone else, I knew I was living moment-to-moment in a temporary, irresistible miracle. The rhythm became click-and-hope, click-and-pray.

And smiles for souvenirs, emblazoned on the faces of a hundred newly-minted Gene Kellys.

“Siiingin’ in the rainnnn…”

Related articles

JUST ENOUGH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS SPEND HALF THEIR LIVES TRYING TO PUT AS MUCH INFORMATION INTO THEIR IMAGES AS POSSIBLE, and the other half trying to remove as much as practicable. Both efforts are in service of the telling of stories, and both approaches are dictated by what a particular photograph is trying to convey.

Sometimes you need the cast of The Ten Commandments to say “humanity”. Other times, just a whisper, an essence of two people talking carries the entire message. That’s where I wound up the other day…with one woman and one very young boy.

Their shared mission was a simple one: hooking up an iPhone Facetime visit with an aunt half a country away. Nothing dramatic, and yet plenty of story to fill a frame with. Story enough, it turned out, for me to get away with weeding out nearly all visual information in the picture, and yet have enough to work with. Time, of course, was also a factor in my choice, since I would be losing a special moment if I stepped into a dark hall and spent precious moments trying to mine it for extra light.

In a second, I realized that silhouettes would carry the magic of the moment without any help from me. What would it matter if I could see the color of my subjects’ clothing, the detail in their hair, even the look on their faces? In short, what would I gain trying to massage an image that was already perfectly eloquent in shadow?

I exposed for the floor in the hall and let everything else go. There was plenty of story there already.

I just had to get out of its way.

ON THE ROAD TO FINDOUT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LATELY I’VE TAKEN TO GRABBING LYRICS OR TITLES FROM POP SONGS TO SUM UP WHAT I WANT TO SAY IN A GIVEN POST, and apparently I haven’t yet kicked the habit. Like the searcher in Cat Stevens’ early ’70’s tune, I am sure that (a) I don’t really know where I’m going most of the time, and (b) the place I’m eventually going to will explain all, eventually. Pretty sunny outlook for a burned out old flower child, I’ll admit, but, especially in photography, the journey is the quest. What we encounter “on the road to findout” is worth the price of the trip.

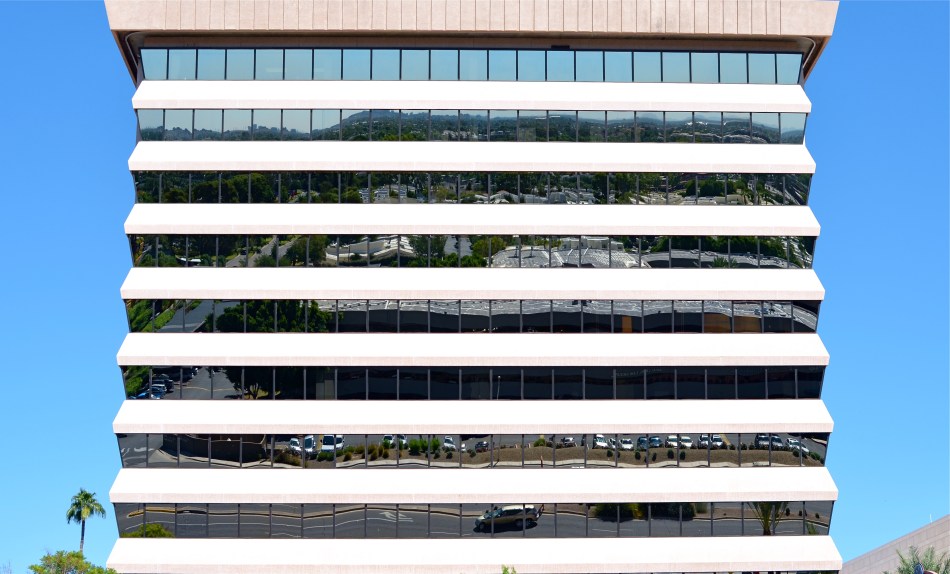

That’s a fancy-pants way of saying that, frequently when I’m on a photo walkabout, I only think I know what I’m looking for. Sometimes I actually snag the object of the expedition, then find that it’s as disappointing as winning that cheap plush toy that looked so wonderful behind the carnival barker’s counter. Such a thing happened this week, when I drove five miles out of my way to revisit a building that had grabbed my attention several months prior. Short term result: mission accomplished…building located and shot. Long term result: what did I think that was going to be? Ugh.

I was walking off my mild disappointment, heading back to my car, and then the mundane act of stowing my camera forced me to rotate my gaze just far enough to see what the midday light was doing to the building across the street. It’s masses of glass looks rather flat and dull by morning, but, near noon, it becomes a slatted mirror, kind of a giant venetian blind, reflecting the entire street scene below and across from itself. The temporary light tilt transforms the place into a surreal display space for about thirty minutes a day, and, had I not been standing exactly where I was across the street at that moment, I would have missed it, and missed the building as a subject for the next, oh, 1,000 years.

Kurt Vonnegut had a dear friend from Europe who always parted from him by hoping that they would meet again in the future if the fates allowed. Only the idiom got crumpled a little in translation, coming out as “if the accident will”. Vonnegut loved that, and so do I.

On the road to findout, we may take wonderful pictures.

If the accident will.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

LEAVE THEM WANTING MORE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PAINTERS INSTINCTIVELY KNOW WHEN IT’S TIME TO REVEAL, AND WHEN IT’S BEST TO CONCEAL. Dark passages or hidden detail within a painting are accepted as part of the storytelling process. That is, what you don’t see can be as valuable a visual element as what you’ve chosen to show. By contrast, many photographers seem to come to this conclusion late , if ever. That is, we’re a little twitchy at not being able to illuminate every corner of our frame, to accurately report all the detail we see.

We try to show everything, and, in so doing, we defeat mystery, denying the viewer his own investigative journey. We insist on making everything obvious. Unlike painters, we don’t trust the darkness. We never “leave them wanting more”.

Fortunately, fate occasionally forces our hand.

The image at the top of this post started out as an attempt to capture the activity of an entire family that was walking their dog near a break in the dense trees that line the creek at Red Rocks Crossing in Sedona, Arizona. The contrast between the truly dark walking paths beneath the trees and the hyper-lit creek and surrounding hardpan is like night and day. The red rocks and anything near them, especially in the noonday sun, reflect back an intense amount of glare, so if your shots are going to include both shady foliage and sunlit areas, you’re going to have to expose for either one or the other. You might be able to get a wider range of tones by bracketing exposures to be combined later in post-processing, but for a handheld shot of moving people, your choices are limited.

I was trying to come to terms with this “either/or” decision when nearly everyone in the family moved away from the creek and into the dense foliage, leaving only one small boy idling at creekside. Feeling my chance of capturing anything draining away, I exposed for the creek, rendering the boy as a silhouette just as he made a break into the woods to rejoin his family. No chance to show detail in his face or figure: he would just be a dark shape against a backdrop of color. The decision to “make things more complicated” had already been taken away from me.

I had what I had.

Turns out that I could not have said “little boy” any better with twice the options. The picture says what it needs to say and does so quietly. No need to over-explain or over-decorate the thing. Darkness had asserted itself as part of the image, and did a better storytelling job all by itself.

I had much more time to calculate many other shots that day, but few of my “plans” panned out as well as the image where I relinquished control completely.

Hmmm….

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter #MPnormaleye

Related articles

- Red Rock Love (missfunshine.wordpress.com)

SECOND SIGHT, SECOND LIFE

Pragmatically “useless” but visually rich: an obsolete flashbulb glows with window light. 1/80 sec., f/5.6, ISO 640, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A DECADE-AND-A-HALF INTO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY, we are still struggling to visually comprehend the marvels of the twentieth. As consumers, we race from innovation to innovation so amazingly fast that we scarcely apprehend the general use of the things we create, much less the underlying aesthetic of their physical forms. We are awash in the ingenuity of vanishing things, but usually don’t think about them beyond what we expect them to supply to our lives. We “see” what things do rather than seeing their essential design.

As photographers, we need not only engage the world as recorders of “reality” but as deliberate re-visualizers of the familiar. By selecting, magnifying, lighting and composing the ordinary with a fresh eye, we literally re-discover it. Second sight gives second life, especially to objects that have outlasted their original purpose. No longer needed on an everyday basis, they can be enjoyed as pure design.

And that’s exciting for anyone creating an image.

The above shot is ridiculously simple in concept. Who can’t recognize the subject, even though it has fallen out of daily use? But change the context, and it’s a discovery. Its inner snarl of silvery filaments, designed to scatter and diffuse light during a photoflash, can also refract light, break it up into component colors, imparting blue, gold, or red glows to the surrounding bulb structure. Doubling its size through use of “the poor man’s macro”, simple screw-on magnifying diopters ahead of a 35mm lens, allows its delicate inner detail to be seen in a way that its “everyday” use never did. Shooting near a window, backed by a non-reflective texture, allows simple sculpting of the indirect light: move a quarter of an inch this way or that, and you’ve dramatically altered the impact.

The object itself, due to the race of time, is now “useless”, but, for this little tabletop scene, it’s a thing made beautiful, apart from its original purpose. It has become something you can make an image from.

Talk about a “lightbulb moment”….

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye.

Related articles

- “A Sight Into My Photographic Mind” (Perspective) (mrphotosmash.wordpress.com)

STRING THEORY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CERTAIN INANIMATE OBJECTS INTERACT WITH THE LIVING TO SUCH A LARGE DEGREE, that, to me, they retain a certain store of energy

even when standing alone. Things that act in the “co-creation” of events or art somehow radiate the echo of the persons who touched them.

Musical instruments, for my mind’s eye, fairly glow with this force, and, as such, are irresistable as still life subjects, since, literally, there is still life emanating from them.

Staging the object just outside the reach of full light helped the violin sort of sculpt itself. 1/800 sec., f/2.5, ISO 100, 35mm prime lens.

A while back I learned that my wife had, for years, held onto a violin once used for the instruction of one of her children. I was eager to examine and photograph it, not because it represented any kind of technical challenge, but because there were so many choices of things to look at in its contours and details. There are many “sites” along various parts of a violin where creation surges forth, and I was eager to see what my choices would look like. Also, given the golden color of the wood, I knew that one of our house’s “super windows”, which admit midday light that is soft and diffused, would lend a warmth to the violin that flash or constant lighting could never do.

Everything in the shoot was done with an f/1.8 35mm prime lens, which is fast enough to illuminate details in mixed light and allows for selectively shallow depth of field where I felt it was useful. Therefore I could shoot in full window light, or, as in the image on the left, pull the violin partly into shadow to force attention on select details.

Although in the topmost image I indulged the regular urge to “tell a story” with a few arbitrary

props, I was eventually more satisfied with close-ups around the body of the violin itself, and, in one case, on the bow. Sometimes you get more by going for less.

One thing is certain: some objects can be captured in a single frame, while others kind of tumble over in your mind, inviting you to revisit, re-imagine, or more widely apprehend everything they have to give the camera. In the case of musical instruments, I find myself returning to the scene of the crime again and again.

They are singing their songs to me, and perhaps over time, I quiet my mind enough to hear them.

And perhaps learn them.

LET THERE BE (MORE) LIGHT

A new piece of glass makes everything look better….even another piece of glass. First day with my new 35mm prime lens, wide open at f/1.8, 1/160 sec., ISO 100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE RECENTLY BEEN EXPERIENCING ONE OF THOSE TIME MACHINE MOMENTS in which I am, again, right back at the beginning of my life as a photographer, aglow with enthusiasm, ripe with innocence, suffused by a feeling that anything can be done with my little black box. This is an intoxication that I call: new lens.

Without fail, every fresh hunk of glass I have ever purchased has produced the same giddy wonder, the same feeling of artistic invincibility. This time out, the toy in question is a Nikon f/1.8 35mm prime lens, and, boy howdy, does this baby perform. For cropped sensor cameras, it “sees” about like the 50mms of old, so its view is almost exactly as the human eye sees, without exaggerated perspective or angular distortion. Like the 50, it is simple, fast, and sharp. Unlike the 50, it doesn’t force me to do as much backing up to get a comfortable framing on people or near objects. The 35 feels a little “roomier”, as if there are a few extra inches of breathing space around my portrait subjects. Also, the focal field of view, even wide open, is fairly wide, so I can get most of your face tack sharp, instead of just an eye and a half. Matter of preference.

All this has made me marvel anew at how fast many of us are generally approaching the age of flashless photography. It’s been a long journey, but soon, outside the realm of formal studio work, where light needs to be deliberately boosted or manipulated, increasingly thirsty lenses and sensors will make available light our willing slave to a greater degree than ever before. For me, a person who believes that flash can create as many problems as it solves, and that it nearly always amounts to a compromise of what I see in my mind, that is good news indeed.

It also makes me think of the first technical efforts to illuminate the dark, such as the camera you see off to the left. The Ermanox, introduced by the German manufacturer Ernemann in 1924, was one of the first big steps in the quest to free humankind of the bulk, unreliability and outright danger of early flash. Its cigarette-pack-sized body was dwarfed by its enormous lens, which, with a focal length of f/2, was speedy enough (1/1000 max shutter) to allow sharp, fast photography in nearly any light. It lost a few points for still being based on the use of (small) glass plates instead of roll film, but it almost single-handedly turned the average man into a stealth shooter, in that you didn’t have to pop in hefting a lotta luggage, as if to scream “HEY, THE PHOTOGRAPHER IS HERE!!” In fact, in the ’20’s and ’30’s, the brilliant amateur shooter Erich Solomon made something of a specialty out of sneaking himself and his tiny Ermanox into high-level government summits and snapping the inner circle at its unguarded best (or worst). Long exposures and blinding flash powders were no longer part of the equation. Candid photography had crawled out of its high chair… and onto the street.

Today or yesterday, this is about more than just technical advancement. The unspoken classism of photography has always been: people with money get great cameras; people without money can make do. Sure, early breakthroughs like the Ermanox made it possible for anyone to take great low-light shots, but at $190.65 in 1920’s dollars, it wasn’t going to be used at most folks’ family picnics. Now, however, that is changing. The walls between “high end” and “entry level” are dissolving. More technical democracy is creeping into the marketplace everyday, and being able to harness available light affordably is a big part of leveling the playing field.

So, lots more of us can feel like a kid with a new toy, er, lens.

Related articles

- Prime Lenses (nikonusa.com)

- Understanding Focal Length (nikonusa.com)

GRABBING THE GIFT

Light makes photography. Embrace light. Admire it. Love it. But above all, know light. Know it for all you are worth, and you will know the key to photography. ——-George Eastman

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN I WAS ASSEMBLING THE FIRST COMPILATION OF MY OWN IMAGES, Juxtapositions, I felt a little awkward about captioning the photos in any way, since they were clearly the work of an unaccomplished amateur. In my native Catholic thinking, my default question was, who the hell did I think I was to pontificate on anything, hmm? Notice that, since you are presently reading the musings of the selfsame unaccomplished amateur, I obviously got over past that obstacle, but anyway…

Needing the book to have some kind of general structure or theme, I decided that, although my own wisdom may not be in demand, there were plenty of thoughts from the greats in the photographic field that were worth re-quoting, and which, correctly placed, might even illustrate or amplify what I was trying to say in my own photos. It was a way of channeling great minds and acknowledging that, pro or amateur, we all started off on the same journey with much the same aims.

Looking at the finished book, I noticed that the two most consistent subjects among the finest minds in photography were (1) light; how to harness it, how to serve it, shape it, seek its ability to frame or exalt a subject and (2) the importance of staying flexible, open, and able to embrace the moment.

Both objectives came into clear focus for me last week. A combination of early sunlight, dense foliage and thick morning fog came together in breathtaking patterns in the high canyon rim streets of Santa Barbara, California. Light was busting out wherever it could, coming through branches and boughs in soft shafts that lent an almost supernatural quality to objects even a few feet away, which, when suffused with this satiny mist, were themselves softened, even abstracted. If there was ever a delicate, temporary gift of light, this was it, and I was suddenly in a hurry, lest it run away from me. Any picture I failed to take in the moment was lost within minutes. Overthinking meant going home empty.

There was no time to carefully read the tyrannical histogram, since I knew it would disapprove of the flood of white that would throw some of my shots off the graph. Likewise I couldn’t “cover” myself by bracketing exposures, since there was so much territory to cover, so many images to attempt before the light could mutate into something else. I needed to be shooting, not fiddling.

Better to burn out than to rust out, as Neil Young famously said. One particular arch of overhanging branches called me. It looked like this:

I was, after all these years, back to complete instinct. Snap shot? Certainly. Snap judgement? Hope not.

I didn’t go home empty. And when I got home, a re-check of one of Ansel Adams’ quotes encouraged me:

Sometimes, I do get to places where God’s ready for somebody to click the shutter.

Look for the moment. Listen for God (sometimes he whispers).

And don’t forget to click.

Related articles

- The 15 Most Popular Photography Tutorials from the 2nd Half of 2012 (digital-photography-school.com)

- What is photography? (bangladesh2u.com)

PERISHABLE

Once upon a time there was a very old apple. Shot real wide and in tight to suck up as much window light as possible and bend the shape a little. 1/50 sec., f/3.5, ISO 160, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I‘M ALMOST TO THE POINT WHERE I DON’T WANT TO THROW ANYTHING AWAY. I’ve written here before about pausing just a beat before chucking out what, on first glance, appears to simply be junk, hoping that a second look will tell me if this rejected thing has any potential as a still life subject. I realize that this admission on my part may conjure images of a pathetic old hoarder whose apartment is packed with swaying columns of yellowed newspapers from 1976 and pizza boxes that have become filing cabinets for old soda bottles, mismatched hardware, and souvenir tickets from Elvis’ last concert.

It’s not that bad.

Yet.

For this I have my wife to thank, since the civilizing influence she brings to my life tends to bank the freakier fires of my aesthetic wanderings. Still, there are hours each day when she’s at work, heh heh, hours during which the mad scavenger rescues the odd object, deluding himself that it is the next big thing in artsy coolness.

That’s what led me to the apple. Actually, I was rooting around in the garage fridge for a beer. The “backup” fridge often acts as a kind of museum of the lost for things we meant to finish eating or bring into the house. The abandoned final four strands of ziti from the restaurant. The sad survivors from the lunch we packed for the office, then left behind since we were running late.

And, in this case, a very old apple.

Having seen gazillions of pieces of fruit frozen in time by photographers, I am sometimes more interested in preserving the moment when Nature has decided to call them home. It’s not like decay is attractive per se, but seeing the instant where time is actually changing the terms of the game for an object, as it always is for us, can be oddly fixating.

So I set this old soldier on a slab and shot away for about a dozen frames. Window light, plain as mud, really zero technique. The colors on the apple were still bright, but the wrinkles had become furrows now, sucking up light and creating strange shadows. Something was leaving, collapsing, vanishing before my eyes, and I wanted to stop it, if only for a second.

And yes, in case you are asking, I did finally throw the thing away.

And got myself a beer.