INVISIBLE MIRACLES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN YOU’RE A CITY THAT HOSTS OVER EIGHT MILLION PEOPLE, certain things, even certain extraordinary things, are bound to get lost in the shuffle. In fact, maybe “shuffle” is the perfect word for what happens to people in a town like New York; they become part of an endless mixing of cards, from Joker to Knave, King to commoner, in an equally endless jumble of encounters. Maybe the lyric “if I can make it there” is more correctly worded “if I can get noticed there”. The sheer speed of the shuffle guarantees that the daily menu of things contains many unseen tragedies, many invisible miracles.

The city is so very crammed with every aspect of the human experiment that it is, by definition, jam-packed with extraordinary talents, great feats. There is, on any given day, an embarrassment of artistic riches that just passes unseen. In other places, the marvelous is more of a rarity. In New York, it’s the very mortar between the bricks. Where else but in New York could a vast greenspace like Central Park be merely part of the local scene, as if it were an old lady’s backyard garden? And where else but in Central Park could a superb saxophonist, like the one seen here, merely be the latest amazing musician you encountered on your morning stroll, halfway between the a capella quartet near the children’s zoo and the gypsy accordionist next to the Bethesda fountain?

The most New York thing about this player’s performance, however, is the degree to which he is being regarded not as an extraordinary musician, but as just another element in the daily mix of sensations. As a frequent visitor that is not a native, my first instinct is still to point a camera at this gentleman, because of course he must be acknowledged, and of course people should struggle to be aware of him. But in Manhattan, there is always the next sensation, the next show, just as, if you miss the latest 7 train, there will be another one just as good arriving in the next few minutes.

Maybe if I were ever to become an actual NYC resident, I would eventually get to the point where more of the city’s on-tap miracles would become invisible to me, so commonplace as not to even merit a camera click. But a regular willingness to be surprised, even amazed, is at the heart of every photographer I have every admired, and, so far, it’s an instinct that has served me well. Maybe I’m just not very sophisticated, living up to the Ohio farmboy rep many have hung on me, the little frog awash in the big pond, and so on.

Maybe I am, indeed, every inch a hayseed. A cornball. A bug-eyed kid agog on his first visit to the circus.

Cool.

I can live with that.

R&G in NYC

By MICHAEL PERKINS

LIFE, IN GENERAL, HAPPENS QUICKLY, a condition that photographers, out of necessity, learn to live with. We decide in mere instants what gets stored into our little boxes, evaluating the “lose/keep” equation with whatever scant time we’re given. Some places, admittedly, afford us decent stretches of contemplation, allowing us to sculpt and shape an image at our leisure. You know; the “park my tripod and wait hours for the ducks” type of picture.

And then there’s shooting in New York.

Shooting on semi-automatic mode, perfect for nailing the basics when speeding through busy Manhattan.

Manhattan may not be the place were impatience was born, but it certainly is the town where it is most practiced. On my recent “reunion” with the city (after five years away), I found myself longing for the occasional moments of recent visits, when I could at least have the luxury of five to ten seconds to size up and calculate a shot. In such cases, as is my usual preference, I would shoot on full manual, delighting in being able to be discriminating, even choosy, in my execution. But this time around, I found myself in the company of several other people wherever I went. Thus, their “mission”, whether it was to catch the 7 train or a Broadway curtain, became my mission, meaning I had to be in nearly constant motion. As a result, manual shots were simply going to take too long, with an endless chorus of “wait just a sec!” from me, answered by annoying looks from the other folks in the crowd.

And thus, for the first time in what seemed forever, I went into R&G, or what time constrained fashion photographers call “run and gun” mode. I pre-selected an automatically determined aperture (typically f/5.6 or f/8), with as much customizing for color and contrast as was called for in most urban situations, and locked it in on one of my Nikon’s “U” mode switches, effectively converting the camera into a point-and-shoot. Don’t get me wrong; semi-automatic modes are great. It’s just that I myself hate to overly rely on them, and even in a situation where I have to use them, I wander back into manual as often as time will permit. However, let’s face it, when you’re bringing up the rear on a crowd of people who are hell bent on getting somewhere fast, you either make the deal and make your life easier, or else make everyone’s life harder.

Whoops. What’s this ring marked “focus” for?

The risk of doing this all came back to haunt me later, when I was back in Los Angeles working a subject where I could take my time, and thus was using a fully manual lens. The first time I got into a minor time crunch, I continued to assume, deep in my lizard brain, that the camera would nail the focus for me, when, in fact, I was neglecting my job of doing it myself, resulting in a passel of gooey, fuzzy shots, all wonderfully composed and exposed, all as soft as a 1910 postcard (see above). The moral here is to be mindful at all times, which for me, usually means taking complete responsibility for a shot. Quite simply, convenience makes me lazy, and laziness makes me careless. Like native New Yorkers who’ve just risen to meet the stimulus level of their very busy city, I accept it as the price of doing business.

AND IT WAS ALL YELLOW….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE LATE COLUMNIST PETE HAMILL ONCE DEFINED A “REAL” NEW YORKER as one who could tell you, in great detail, what a great town New York used to be. I was born in Ohio, but, as I married a woman who grew up in the city and its immediate environs, I have been privileged to visit there scads of times over the past twenty years, enough that I have been able to compile my own personal list of longings for Things That Have Gone Away in the Apple. There are the usual pangs for beloved bars and restaurants; bittersweet memories of buildings that fell to the unfeeling juggernaut of Progress; and the more abstract list of things that could be called How We Used To Do Things Around Here.

For me, one of those vanishing signposts of all things Noo Yawk is the great American taxi.

Take Me Uptown, October 12, 2024

As the gig economy has more or less neutered the cab industry in most cities, the ubiquitous river of yellow Checkers that used to flood every major NYC street at all turns is now a trickle, as Uber and Lyft drivers work in their own personal vehicles, causing one of the major visual signatures of life in the city to ebb, like a gradually disintegrating phantom. As much as the subway or sidewalk hot dog wagons, cabs are a cue to the eye, perhaps even the heart, that a distinct thing called “New York” endures. As a photographer, I’ve caught many huge flocks of them careening down the avenue over the years, even on days when I couldn’t, for the life of me, get even one to stop for me. Now, on a recent trip that was my first time in New York in nearly five years, spotting even one Checker was something of an event for me, and suddenly posed a bit of a photographic challenge.

The problem with taxis, now, is to show not only the physical object itself, but to visually suggest that it is slowly going ghost, fading into extinction. In such situations, I find myself with the always-tricky test of trying to photograph a feeling, finding that mere reality is, somehow, inadequate to the task. It bears stating that I am, typically, a straight-out-of-the-camera guy; I make my best effort to say everything I have to say before I click the shutter. That’s neither right nor wrong; it’s just the way I roll. And so, for me to lean heavily on post-tweak processing, I have to really be after something specific that I believe is outside of the power of the camera itself. The above shot, leaning heavily on such dream-feel, is even more ironic, because the Checker in question is no longer a working unit, but a prop parked permanently in front of a funky-chic boutique hotel. In other words, a museum piece. A relic.

Like moi.

Pete Hamill knew that New York’s only perpetual export is change. Managing that change means managing ourselves; knowing what to say hello and goodbye to; and hoping that we guess right most of the time on what’s worth keeping. Or maybe, just to forever hear a New York cabbie shouting over his shoulder to us, “Where To, Mac?”

REDEMPTION, ARRIVING ON TRACK 11

In the old time, you arrived at Pennsylvania Station at the train platform. You went up the stairs to heaven. Make that Manhattan. And we shall have it again. Praise All.

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan

Main concourse, Moynihan Train Hall, New York City

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR THOSE WHO LIVE OUTSIDE NEW YORK CITY, it is hard to express the sense of loss that’s is still felt locally over the 1963 demolition of the old Penn Station railroad terminal. Crumbling from age and neglect, it was one of hundreds of landmarks that fell to the wrecking ball in an age where so-called “urban renewal” reigned supreme, and its end has continued to haunt urban planners ever since, as the very definition of a wasted opportunity. Today, classic buildings are more typically salvaged and repurposed, allowing their storied legacies to write new chapters for succeeding generations. Penn Station’s death was the Original Sin of a more careless age.

But sins can sometimes be redeemed.

“The Hive” , a dramatic art installation inside the 21st Street entrance to Moynihan Train Hall.

Around 2000, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who, years before, had worked as a shoeshine boy inside the first Penn Station (which was “replaced” by a grim dungeon in the ’60’s on its original site), began to float the idea of augmenting rail access to Amtrak and other carriers by recreating the majesty of the old building in the most obvious place; across the street. Turns out that the terminal had a near-twin, just beyond the crosswalk on Eighth Avenue in New York’s old main post office, which, like the train station, was designed by the legendary firm of McKim, Mead & White. By the start of the 21st century, the post office, by then known as the James Farley building, had already begun to move many of its operations to other facilities, heading for white elephant status in one of the city’s most expensive neighborhoods. By the senator’s death in 2003, funding for what many locals were already calling the Moynihan Train Hall went through years of fiscal stop-and-start, careening like a foster child through the hands of half a dozen different potential sponsors. Construction finally began in 2017, with special care taken to preserve and restore the post office’s massive colonnade entrance, which was, itself, protected with landmark status.

On January 1, 2021, almost as a symbol of New York’s resurrection following its year-long struggle as the first epicenter of the Covid pandemic, the completed Moynihan Train Hall was finally dedicated by New York governor Andrew Cuomo. My photographs of the site now join those of millions of others as testimony to the power of the human imagination, as do the Hall’s waiting-room murals, which illustrate the grandeur of the terminal’s long-vanished predecessor, poignant reminders of the new building’s purpose in redeeming the sin of letting the old one be lost. Among the mural captions are the words of Daniel Patrick Moynihan himself, celebrating the town’s unique trove of tradition and talent:

Where else but in New York could you tear down a beautiful beaux-arts building and find another one across the street?

Amen. Praise all.

THE VERY PICTURE OF….ANOTHER PICTURE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I CAN’T BE THE ONLY PERSON WHO HAS EVER SEEN this classic image of photographer Margaret Bourke-White peering over a stainless-steel projection near the top of the Chrysler Building and asked themself, “so who in heck is taking this picture?”

Oh sure, we know the basics of the story. In 1930, The skyscraper’s owners invited the already-renowned MBW to set up her wooden view camera on one of the structure’s eight gleaming eagle’s heads at the 61st floor, and take in what was then an extremely privileged view of Manhattan. The building, not yet quite completed, would eventually top out at 1,046 feet (77 stories) above the pavement, winning one of the city’s most celebrated “skyscraper wars”, cinching its right to Tallest stature by virtue of the gigantic steel spire that served as its crown. Bourke-White, whose studio was then located in Cleveland, had already considered moving to NYC to be nearer her employers at Fortune magazine, and once she ascended to take in the, er, eagle’s-eye view, she decided that the Chrysler itself should be her new HQ, all the better for her to be the two eagles on the corner where she shot, which she nicknamed “Min” and “Bill” after a popular movie of the time.

But who else made the ascent that day, to take a picture of her.. taking a picture?

Introducing the nearly-forgotten Oscar Graubner, Margaret’s full-time darkroom assistant and amateur snapper, who often traveled with Bourke-White on what was, by the early ’30’s, already a global trajectory, a career which would take her from the opening of hydroelectric dams (the first Life magazine cover ever) to photo-essays in the young Soviet Union to, eventually, every major theatre in the European war and the India-Pakistan schism. Graubner was part of what built MBW’s nickname of “Maggie The Indestructible”, and, by chance, snapped the best image of her at work. Strangely, his picture of her doing her thing from the top of the Chrysler has now been viewed many millions of times more than any pictures she actually made herself from up there. The history of photography may be peopled by giants, but it’s punctuated by those who toil in their immense shadows.

THE RISING, COMPLETED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

September 11, 2022

TWENTY-ONE YEARS. The life of a legally arrived adult. The space of a generation. How much time has passed since the horror of 9/11, and yet how immediate remains its emotional resonance. Photographers the world over, then and now, have tried to capture the surreal universal gasp of shock that unfurled in those few minutes on 9/11/01. And now, today, as the wound has become the scar and the flash has morphed into a flashback, an entirely reborn Lower Manhattan both recalls the history and serves, ironically, to obliterate it. For those who make images, the present era is a fraught one.

The first pictures, of course, were of the burning, the dying, the national open grave. The second wave of images was of the remains of people and buildings being literally trucked away, of a starched, scraped plain that promised a a repurposing. Coming soon on this site. Flags and markers and makeshift memorials, as holy as they were to many, were soon ushered offstage, as New York, the city that knows more about staging revivals than any other, prepared for a new production. As a frequent visitor to New York over the past fifteen years, I was present at many of the stages of the set design.

Lights, action, rebirth.

I have tried to have it both ways with the pictures I have made in the area, with both respectful homages to the sacramentals within the September 11th museum and the memorial pools, and the explosion of creative energy that mushroomed into the new WTC plaza. It’s been a high-wire act, artistically and emotionally, but I feel an urge now, to move my lens almost exclusively to The Next Act, since it now exists not merely as a yearning for a return to normalcy, but as a defiant fait d’accompli, another proof that New Yorkers are always about Getting On With It.

This image, with its lettered reflection of the 90 Church Street Post Office (which was itself littered with falling debris of the twin towers’ collapse), is my attempt to capture past survivors and forward strivers in the same frame, to say, yes, amen, a prayer for the dying, but also yes, hell yes, for the indomitability of America, which honors its founders best when doubters prematurely pronounce it out for the count.

We are back.

We are always back.

We are staying.

SOUL-VENIRS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

DEPENDING ON WHEN YOU FIRST READ THIS POST, the events of The Horror Year 2020 may well already have sealed the fate of the establishment I write about today. The perishability of current events is one of the reasons that, over the last decade, I have almost completely kept “news” items out of the pages of The Normal Eye. Such stories age worse than limburger in the hot sun, and I have mostly chosen to address the eternal questions that affect photography, those universal struggles that occur in every age, regardless of what’s on the front page on any given day.

But part of photography is always about that very perishability, the race to document or capture things before they vanish beneath the tides of time. And so I find myself calling attention to what is, at this moment, a poignant by-product of the Horror Year. On the surface, it’s just about the potential closing of a bookstore, hardly worth a ripple in the tragic tsunami of business failures and bankruptcies that are the persistent drumbeat of our current time. On another level, it’s about one of the most familiar and venerable of bookstores anywhere in America, the Strand in New York City, an establishment whose very existence symbolizes survival. Once part of a glorious 44-store district in the city known as Book Row, The Strand, at age 93, is the last man standing, its 2.5 million volumes serving as not merely a commercial concern but a community center, a cultural touchstone in the life of Manhattanites. Under the care of Nancy Bass Wyden, the granddaughter of the founder, the Strand, in this Season of the Plague, has crawled through the first months of the pandemic with some federal help, but, at this writing, it faces nothing short of extinction, and just this week, in October of 2020, the store has posted appeals to current and former customers around the world…a desperate S.O.S. that simply says, if you love us, save us. Within twenty-four hours of the story going public, the store’s website was so flooded with responses that it crashed.

And there my crystal ball goes dark. At the time of this writing, I can’t predict whether you, the someday reader, are smiling because the Strand has been saved or shedding a quiet tear at its passing. The one reason I felt compelled to cite a fast- moving news story at all in this forum is that it reminds me why we make pictures of things in the first place. Because they close. They fade. They burn. They fall to enemy bombs. To floods. To negligence. To our own failed memories. Photographs are one of the only hedges against the dread onslaught of temporal decay. And they themselves are also subject to that rot, becoming lost, left behind, forgotten. Beyond mere “souvenirs” of lost times, they are soul-venirs, testaments of times ago. For this reason, I went rooting this week through my old images of the Strand from the last twenty years. None of them are masterpieces, but all of them are markers, headstones for a time, and a condition, and a way of life, not only for New York but for your town, my town. Time is fleeting. Therefore make pictures. Sometimes, as Yogi Berra famously said, “nostalgia ain’t what it used to be”, but even a smudged shadow of history may someday be all we’ve got. Better to grab a box and go shadow-catching.

A NEW BEEHIVE IN AN OLD APPLE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

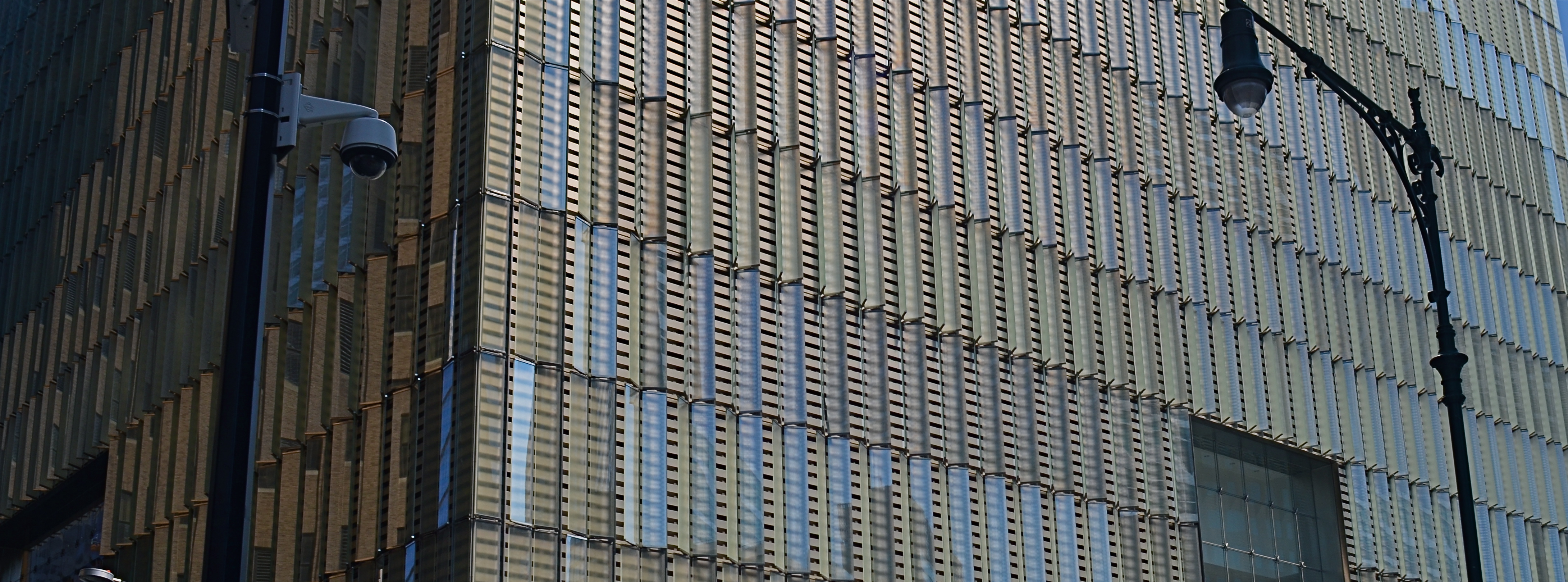

IT HAS BEEN CALLED “THE EIFFEL TOWER OF AMERICA”, a “stairway to nowhere”, a “bold addition to the city’s landscape” and “an eyesore”,…….in other words, a new structure in New York City. Whatever its eventual place in the hearts of Manhattanites, architect Thomas Heatherwick’s Vessel, a hollow, honeycombed tower of open staircases, viewing landings and dizzying geometry, all sixteen stories of it, has become the visual exclamation point for the continuing explosion of shops and businesses known as Hudson Yards, a project so huge it may not max out for another decade. At this writing, it’s late 2019, and the tower’s creators, who claim the name “vessel” is just a transitional one, have already weathered a short tsunami of plaudits and protests since the beehive’s opening earlier in the spring. And in a city defined by bold visual signatures, the structure seems destined to become a darling for photographers, especially at its current newborn phase, in which there is, as yet, no “official” way of viewing it, no established postcard depiction to inhibit or limit individual visions. It’s at this first phase in a landmark’s life that all captures are equal: it’s the photographic equivalent of the Wild West.

Vessel sits near the periphery of the High Line, the internationally praised West Side reclamation of the New York Central Railway’s old raised infrastructure, which now welcomes millions of strolling visitors and locals each year along its 1.45 miles of twisty, landscaped boardwalks, and has acted as the launch pad for recovery of the entire area, including Hudson Yards’ forest of skyscrapers and high-end shops. The first phase of the Yards is crowned by a glistening five-story mall whose massive glass facing wall is directly opposite Vessel. On the day when I visited, the free timed daily tickets to the inside of the honeycomb were all gone, so viewing it in the regular fashion was off the table. However, every floor of the mall has a spectacular view of the structure and its surrounding plaza, which actually appealed to me almost as much as a trip inside. The combination of reflection, refraction, and the golden glow of the approaching sunset made for a slightly kaleidoscopic effect, and so I decided to re-configure my plans. As mentioned before, the utter newness of the tower plays superbly well into photographic experimentation, as its design seems to present a completely different experience to the viewer every few feet, a very democratic sensation that rewards every visitor in a distinctly personal way. Besides, part of the fun of seeing new things in New York is weighing the hoorays and howls against each other and then making up your own mind.

In a city that has seen both P.T. Barnum’s dime museum and Penn Station fade from the scene over the centuries, it’s useless to guess whether Vessel is eventually regarded as a must-see or a fizzle. But it doesn’t matter much either way. Right now, it is neither building nor dwelling. Like Eiffel, it just is, and maybe that’ll be enough. In the meantime, photographers are using the opportunity of its present existence to celebrate the uncertainty that informs the making of the best pictures.

A BREAK IN THE CHAIN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU RECOGNIZE THE ELEMENTS OF THEIR STRANGE VISUAL SIGNATURES AT ONCE: garish neon; outsized, surreal props: homemade window signs: and, always, for the storefronts of aging or vanishing businesses, the feeling that this is the creation of a single owner, not a faceless chain. It’s the Great American Mom ‘n’ Pop, and it is always flitting near the edge of extinction. And like all things endangered, it is fitting fodder for the photographer…for although these strange displays don’t include the standard features of the human face, yet still a human portrait of sorts can be made from their humble elements.

If you ever get the chance, thumb through an enormous volume called Store Front: The Disappearing Face of New York by James and Karla Murray (Gingko Press, 2008). Shot on simple 35mm film, this amazing collection offers both images and backstories from all five boroughs in the greater NYT metro, organized by region. The caption data for the pictures is often the personal remembrances of the most recent operators of the various neighborhood’s delis, dry cleaners, beauty salons, supply houses and markets, most of them in continuous operation for most or all of the twentieth century, many closing up forever even as the book was going to press. The “front” is a kind of short story, a miniature play about who we were, what we sought, what we settled for. Often the buildings have risen or fallen with their respective neighborhoods, their entrances falling prey to crime, time, neglect. Several owners lament not being able to get the parts to keep their neon signs in repair. Others wish they could add a new awning, a fresh coat of paint. And always, as the fronts wink out, regentrification rears its trendy head. But it doesn’t bring new good times for the old place. Instead, it erases their stories…with apartment blocks, Pizza Huts, a Verizon store.

The image seen here, along Central Avenue is Phoenix, Arizona, boasts of (at least) a world of cheese, at a deli which is short on space but long on local flavor. In the American Southwest, as compared to other cities, neighborhoods don’t often get to live long enough to become “venerable” or “historic”, such is the short loop between grand openings and final swings of the wrecking ball. In more traditional urban spaces, everything old is occasionally new again. In Phoenix, it’s old, and then….just gone. The insanely disproportionate worship of the new and shiny in this part of the country can be exhilarating, but the real loss it engenders is sad and final in the way that doesn’t always happen back east. As a consequence, urban chroniclers in this neck o’ the desert must keep their cameras forever at the ready. You can never assume that you’ll get that picture the next time you swing through the neighborhood. Because the neighborhood itself may not be around.

For photographic purposes, I believe that storefronts are best shot straight-on (rather than at an angle) so that their left-to-right information reads like a well-dressed theatre stage. This also makes us look at them differently than we do as either pedestrians or drivers, where they tend to slide along the edge of our periphery largely unnoticed. Some of them benefit from being decorated by the figures of passersby: others appear more poignant standing alone. The main thing, if for no other reason except to create a break in the “chain migration”, is to maintain a record. There is a reason why so many “then and now” books of urban photographs are so jarring in their contrasting images. We live so quickly that we simply do not record our environment even through the daily process of using it. We need reminders for reference, even on the things that we should be eventually letting go of. And the camera puts down mileposts in a compelling way. It marks. It delineates, stating in concrete terms, we were that, and now we’re this. I believe in getting out that tape measure on occasion. I think it matters.

THE LOVELY BONES

Oversized marble columns support the high lobby ceiling at 195 Broadway, former New York home of AT&T.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

195 BROADWAY IN LOWER MANHATTAN is one of hundreds of buildings that might escape your notice upon your first walk through the city’s financial district. Less garish than its gothic neighbor, the Woolworth Building and a lot shorter than its big-shouldered brethren, the 29-floor landmark doesn’t shout for attention. Its true beauty emerges when you walk inside the somewhat restricted lobby, take the measure of the “bones” of its regal inner structure, and breathe in its storied history. Completed in 1916 after AT&T moved its American headquarters from Boston to New York, 195 was the strong, silent type of skyscraper….functional, neo-classic, but restrained, understated. As a largely urban photographer, I try to keep track of structures that have outlasted several uses and landlords, carrying their essence forward through decades of shifting styles and fashions. It’s the totality of what has made them last that makes them interesting to me, more than any single fillip or ornament.

But ornament, as a visual metaphor for the new (20th) century of American technological dominance, was built into 195 Broadway from the start, both inside and out. Paul Manship, the sculptor whose public works, like the golden Prometheus statue at Rockefeller Plaza, still dot the Manhattan map, created one of his first major works, The Four Elements, as bronze relief’s on 195’s lower facades, his love of Greek and Roman mythology weaving itself into the Moderne movement (later re-dubbed as Art Deco). Architect William Bosworth took the Doric columns which usually adorned the outside approaches of other buildings and brought them into 195’s lobby, all 43 of them, their wondrous marble reflecting a variety of colors from the teeming parade of streetside traffic. And sculptor Chester Beach used the same lobby to commemorate the building’s role as one half of the first transcontinental phone line in 1915 with Service To The Nation In Peace And War, a bronze relief of a headphone-wearing hero standing under a marble globe of the Earth, bookended by classic figures and flanked by lightning bolts.

195’s long run includes the titles like the Telephone Building, the Telegraph Building, the Western Union Building, as well as appearances in popular culture, like its portrayal of Charlie Sheen’s office building in Wall Street. Sadly, a few of its most salient features have moved on, like the gilded 24-foot tall winged male figure originally known as Genius Of Telegraphy, which topped the pyramidal roof of the tower on the west side of the building until 1980, when it followed AT&T’s relocation to Dallas, Texas. However, the remaining treasures of 195 Broadway are still a delight for both human and camera eyes. Good buildings often present their quietest faces to the street. But look beyond the skin of the survivors, and marvel at the solid bones beneath.

TABLE FOR ONE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GREAT IRONIC CLICHE OF CITIES is how they smash millions of people together while also keeping them completely isolated from each other, forcing the seeming intersections of lives that, below the surface, are still tragically alienated. Photography, coming of age as it did at roughly the same time as the global rise of cities, became accustomed, early on, with showing both the mad crush and the killing melancholy of these strange streets. We take group shots within which, hidden in plain sight, linger poignant solo portraits. The thrill of learning to speak both messages with a camera in one instant is why we do this thing.

Gray days, especially the fat batch of them I recently harvested in Manhattan, do half of my street photographer’s job for me, deepening colors and shadows in what can quickly become an experiment in underexposure, a lab which, in turn, profoundly alters mood. Things that were somber to begin with become absolutely leaden, with feelings running to extremes on the merest of subjects and forcing every impression through a muted filter. It’s what makes it out the back end of that filter that determines what kind of picture I’ll get.

The two diners in this scene are an arbitrary interpretation…..a judgement call that, on a bright day, I might have made completely differently. They are in parallel arrangement, so they both are looking off to the right, never across at each other. Does this make them lonely, or merely alone? The fact that there is one man and one woman in the composition doesn’t necessarily denote desperate or disconnected lives, but isn’t there at least a slight temptation for the viewer to read the image that way? And then there is our habit of seeing this kind of color palette as moody, sad, contemplative. The limited amount of light in the frame, as much as any other element, “tells” us what to feel about the entire scene. Or does it?

Now, of course, if you were to pack a roomful of other photogs into the same room alongside me to shoot the same image under the exact same conditions, you would very likely get a wider variety of readings. One such reading might suggest that both of these people were thoroughly enjoying a pleasant, quiet lunch, part of a lifelong pattern of contented fulfillment. Or not.

Cities are composed of millions of eyes backed by many more millions of inherited viewpoints on what defines big words like lonely, isolated, sad, thoughtful, and so on. But all of us, regardless of approach, are taking the strange city yin/yang of get closer/go away and trying to extract our own meaning from it.

BIG STORIES, LITTLE STORIES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT ISN’T THE EASIEST THING, upstaging one of the world’s key postcard views. And yet, in final analysis, people should rank higher, in the photographer’s eye, than the things people build for their use. So it should come as no surprise that, to the patient eye, human-sized scene stealers abound everywhere, big setting or small.

This view of the southern side of the Brooklyn Bridge certainly needs no additional context, and yet, the nearby Pier 17 promenade, repaired and re-imagined as all-new public space near the Fulton Street market region in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy (and shown here), provides a daily flood of people-watching opportunity. Indeed, almost any other framing along the deck at the moment this shot was taken would show just how much company the ladies seen here actually had on this particular Saturday evening. The word throng definitely applied, with just about any other composition revealing hundreds of singles, couples, and families crowding the Pier’s restaurants, bars, kiosks, tour boats and viewing rails……however, we have decided, for the moment, to concentrate on these two ladies, and the bond of friendship that is more than enough story to power a photograph.

What you can’t hear, and they clearly could, is the incredible music beat being pumped throughout the pier. What you can certainly see is that you don’t have to be standing, or even using your entire body, to dance…to feel….to be one with that beat. In truth, given that the woman at left is sporting a pair of crutches, “dancing” becomes the living embodiment of the motto work what you got, with mere hand claps getting the job done. As for the lady in purple, a single, upraised hand and a bowed head testify, yes, I’m feelin‘ it. They are both sitting, but they are in no way sedentary. It’s on.

And while all this is going on, just like that, the Great Bridge has dropped to second billing. A backdrop. Atmosphere. Which is something that can happen anywhere, but especially here. For as they know all too well on Broadway, on any given night, the understudy can take stage instead of the star.

And steal the show.

ON DISPLAY

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ALTHOUGH MUSEUMS ARE DESIGNED as repositories of history’s greatest stories, I often find that the most compelling narratives within those elegant walls, for the photographer in me, are provided by the visitors rather than the exhibits.

We’ve seen this effect at zoos: sometimes the guy outside the ape house bears a closer resemblance to a gorilla then the occupant within. With the museum experience, making controlled, serene exposures of the artifacts is never as interesting as turning your reporter’s eye on the folks who came in the door. The juxtaposition of all the museum’s starched, arbitrary order with humanity’s marvelously random energy creates a beautifully strange staging site for social interaction….great hunting for street shooters.

The sculpture gallery shown here, one of the most beautiful rooms in Manhattan’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, is certainly “picturesque”enough all by itself. However when the room is used to frame the chessboard-like weaving of live humans into the pattern of sculpted figures, it can create its own unique visual choreography, including the mother who would love to bottle-bribe her baby long enough to finish just one more chapter.

Anyone who’s visited The Normal Eye over the years recognizes this museum-as-social-laboratory angle is a consistent theme for me. I just love to mash-up big art boxes with the people who visit them. Sometimes all you get is statues. Other times, one kind of “exhibit” feeds off the other, and magic happens.

GROUND ZERO FOR VALOR

Sheared in half under the collapsed WTC’s North Tower, Ladder Company 3’s apparatus truck stands guard in the 9/11 Memorial Museum’s underground exhibit space.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BEFORE THE ELEVENTH OF SEPTEMBER WAS DEFINED, for the New York Fire Department’s Ladder Company Number 3, by grief, the date had long stood as a milestone of devotion. Dedicated on September 11, 1865, Ladder 3 as one of Manhattan’s first fire companies, “the 3” was well on target toward its sesquicentennial on the morning that eleven of its finest perished while trying to evacuate the 40th floor of the doomed North Tower at the World Trade Center.* Death above was mirrored by destruction below: parked along West Street, the 3’s apparatus (ladder) truck was sheared in half, corkscrewed into a clawed snarl by the astonishing force of the building’s collapse.

And so it happened that one of the most poignant symbols of American valor was entombed, literally, at the epicenter of the nation’s most raw, most anguished loss, the geographic coordinates that quickly came to be called Ground Zero. However, the 3’s truck would not immediately serve as an official visual headstone, a graphic barometer of our loss. That day would have to wait.

First would be the accounting, the sorting out. As ashes were sifted and rebirth begun in this most vigorously contested patch of Lower Manhattan, the twisted remains of Ladder 3 were removed, the truck warehoused at JFK airport, silently sequestered against the day it would be re-purposed as a red-and-rust jewel in the reverent setting of the 9/11 memorial museum.

That resurrection and re-internment, a mixture of sacred fervor and steely defiance, would come on July 20, 2011, when the returned Ladder 3 apparatus truck, swaddled in U.S. and FDNY flags, would be lowered 70 feet down into the subterranean display space that serves as the nerve center of the museum. Now, before daily batteries of Nikons, Canons, and iPhones, its silent testimony can follow millions back home, the countless new images illustrating, as no words could, the full impact of history. Standing in as a grave marker for the thousands of human remains housed invisibly nearby, Ladder 3’s gnarled visage would pose as a surrogate, a way of marking valor’s Ground Zero.

* * * * *

*Ladder 3, in firefighter parlance, was “running heavy” on the morning of 9/11. The attack occurred almost precisely at the company’s change of shift, with both first and second shift crews remaining on duty to combat the catastrophe. This horrific quirk of fate doubled the 3’s losses at the site, claiming the lives of Captain Patrick “Paddy” Brown, Lt. Kevin W. Donnelly, Michael Carroll, James Raymond Coyle, Gerard Dewan, Jeffrey John Giordano, Joseph Maloney, John Kevin McAvoy, Timothy Patrick McSweeney, Joseph J. Ogden, and John Olson.

A NEW PATH

A dream of life comes to me. Come on up for the rising tonight—-Bruce Springsteen

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE POST 9/11 RESURRECTION OF LOWER MANHATTAN might have begun as a kind of act of defiance, a refusal to knuckle under to fear in the aftermath of the largest attack in history on American soil. Somewhere amidst the tears and rage, however, the project to re-establish this crucial corner of New York City moved onto a higher plane, transitioning from anger to elegance, mourning to…morning. And now, for both casual travelers and astounded visitors, the master plan for the area is an ever-blooming monument to faith. To excellence.

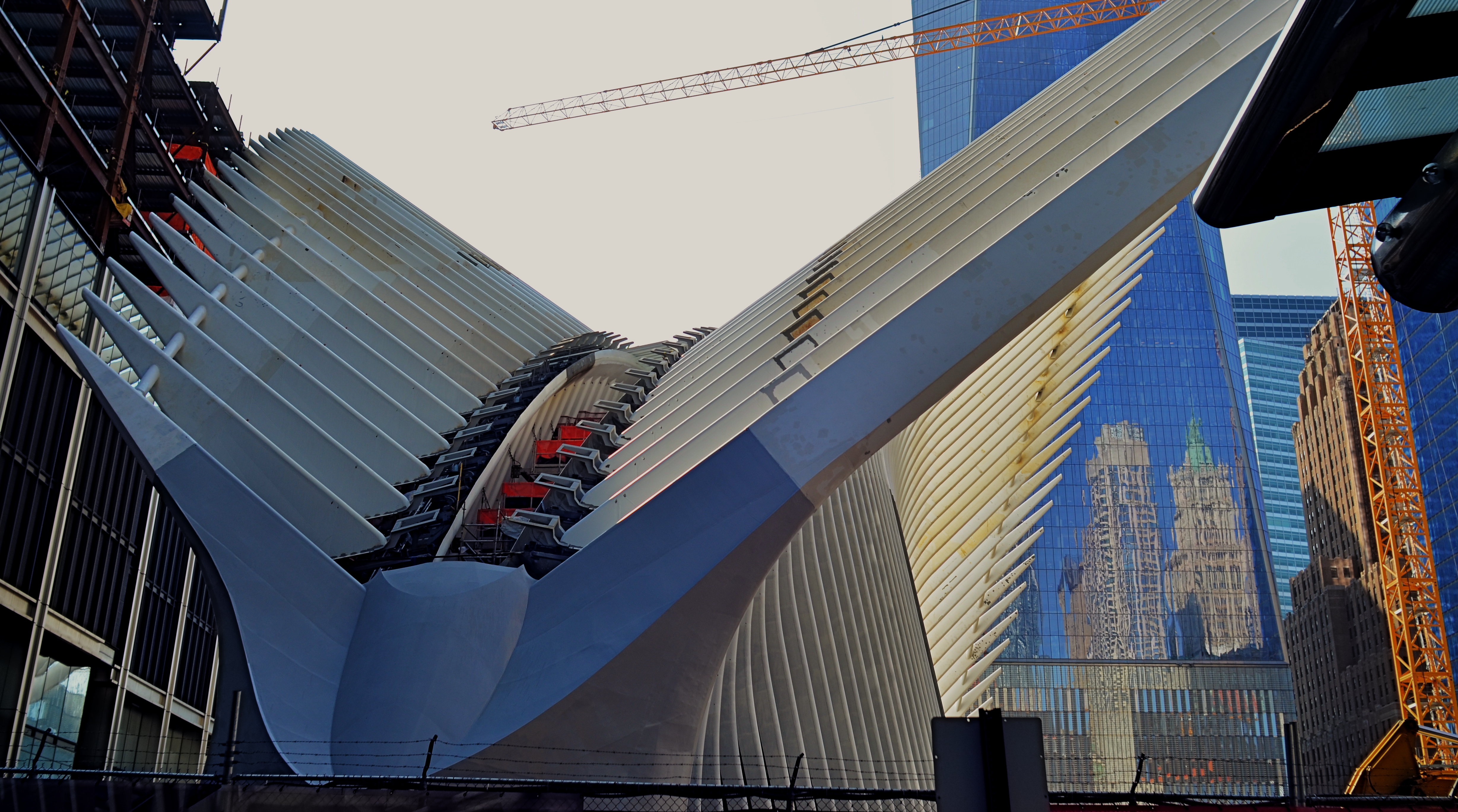

Photographers from around the world have known, from the days of the first cleanups, that an amazing opportunity for historic documentation was unfolding on this hallowed ground, and their images have provided an invaluable service in tracking the city’s transition between two distinct eras. The first two mile-markers in this transformation, the openings of World Trade Center One and the 9/11 Memorial Museum, have been interpreted in a global cascade of visual impressions, occurring, as they have, in the first explosion of social media and digital imaging. And now, the third piece of the puzzle, the stunning new Oculus PATH terminal, is nearly ready to serve as the proof that the city, along with all its millions of comings and goings, is still very much open for business.

Oculus Aloft: the steel wings of the new PATH terminal for New York’s World Trade Center, nearing completion in 2015.

Photographers have already made a visit to Oculus something of a pilgrimage, and, looking over the first few photos to emerge from their visits, it might be closer, architecturally, to a religious experience. Designed by Santiago Calatrava, the structure, presenting its ribbed wings to the skies like an abstract bird of prey, resembles, within, a kind of sci-fi cathedral of kaleidoscopic light effects, serving as both monument and utility. An inventory of its features and a gallery of interior images can be seen here.

And, of course, this is New York, so opinion on the Oculus’ value, from poetic prayers to crass carping, will go through the usual grappling match. But, whatever one’s eventual take on the project, its power as a statement….of survival, of power, of hope, and, yes, of defiance, cannot be denied. To date, I’ve only been able to photograph limited parts of the construction phase (see above), but I will be back after the baby’s born. And my dreams will collide with Oculus’ own, and something magical will happen inside a box.

Make your way to Manhattan, and let your own camera weigh in on the new arrival.

Come On Up For The Rising.

FACE TIME

The resurrected World Trade Center, as seen at eye (rather than “craning neck”) level. 1/125 sec., f/5.6, ISO 100, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I AM OFTEN ASKED WHY ARCHITECTURE FIGURES SO STRONGLY in my photography, and I can only really put part of my answer into words. That’s what the pictures are for. I imagine that the question itself is an expression of a kind of disappointment that my work doesn’t focus as much on faces, as if the best kind of pictures are “people pictures”, with every other imaging category trailing far behind. But I reject that notion, and contend that, in studying buildings, I am also studying the people who make them.

Buildings can be read just as easily as a smile or a frown. Some of them are grimaces. Some of them are grins. Some of them show weary resignation, despair, joy. Architecture is, after all, the work of the human hand and heart, a creative interpretation of space. To make a statement? To answer a need? The furrowed brows of older towers gives way to the sunny snicker of newborn skyscrapers. And all of it is readable.

In photography, we are revealing a story, a viewpoint, or an origin in everything we point at. Some buildings, as in the case of the first newly rebuilt World Trade Center (seen above), are so famous that it’s a struggle to see any new stories in them, as the most familiar narratives blot the others out of view. Others spend their entire lives in obscurity, so any image of them is a surprise. And always, there are the background issues. Who made it? What was meant for it, or by it? What world gave birth to this idea, these designs, those aims?

Photography is about both revelation and concealment. Buildings, as one of the only things we leave behind to mark our having passed this way, are testaments. Read their faces. No less than a birthday snapshot, theirs is a human interest story.

INTERACTIONS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S FAIRLY EASY TO FIGURE OUT WHERE TO TAKE YOUR CAMERA if you are trying to visually depict a vibe of peace and quiet. Landscapes often project their serenity onto images with little translation loss, and you can extract that feeling from just about any mountain or pond. For the street photographer, however, mining the most in terms of human stories is more particularly about locations, and not all of them are created equal.

Street work provides the most fodder for storytelling images in places where dramatically concentrated interactions occur between people. One hundred years ago, it might have been the risk and ravage of Ellis Island. On any given sports Sunday, the opposing dreams that surround the local team’s home stadium might provide a rich locale. But whatever the site, social contention, or at least the possibility of it, generates a special energy that feeds the camera.

In New York City, the stretch of Fifth Avenue that faces the eastern side of the Empire State Building is one such rich petri dish, as the street-savvy natives and the greener-than-grass tourists collide in endless negotiation. Joe Visitor needs a postcard, a tee-shirt, a coffee mug, or a discounted pass to the ESB observation deck, and Joe Hometown is there to move the goods. Terms are hashed over. Information slithers in and out a dozen languages, commingling with the verbal jazz of Manhattan-speak. Deals are both struck and walked away from. And as a result, stories flow quickly past nearly every part of the street in regular tidal surges. You just pick a spot and the pictures literally come to you.

In these images, two very different tales unfold in nearly an identical part of the block. In the first, bike rickshaw drivers negotiate a tourist fare. How long, how far, how much? In the second, two regulars demonstrate that, in New York, there is always the waiting. For the light. For parking. For someone to clear away, clear out or show up. But always, the waiting. These are both little stories, but the street they occur on is a stage that is set, struck and re-set constantly as the day unfolds. A hundred one-act plays a day circle around those who want and those who can provide.

Manhattan is always a place of great comings and goings, and here, in front of the most iconic skyscraper on earth, those who haven’t seen anything do business with those who’ve seen it all. Street photography is about opportunity and location. Some days give you one or the other. Here, in the city that never sleeps, both are as plentiful as taxicabs.

THE PUSH AND THE PULL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NEW YORK CITY IS A VERY IRONIC CANVAS. Artists who set brush upon that canvas may think they are attempting to depict something outside themselves, but what they show actually reveals very personal things. There are more stories than all the storytellers in the world can ever hope to render…in paint, in print, or through the lens of a camera, and while some of us entertain the notion that we are adding this commentary objectively, that, plainly, is impossible.

From handheld luggage to emotional baggage, everyone brings something to New York, layering their own dreams and dreads onto the multi-story sandwich of human experience that makes it the world’s most unique social laboratory. Hard as it is on the artistic ego, one can’t make the statement that defines the city. Wiser minds from Walt Whitman to Langston Hughes to Bob Dylan have tried, and they have all contributed their versions….wonderful versions. But the story can never be completed. New York won’t be contained by mere words and images. It is, like the song says, a state of mind.

Still, trying to scale the mountain can be fun. So, with this post, The Normal Eye has added a new gallery tab at the top of the page to share a few recent takes on my own ongoing love affair with the Apple. The title, I’ll Take Manhattan, is hardly original, but it is easy to remember. I have done essays on NYC before, but, this time out, I strove to focus as much on the rhythm of people as on the staggering scope of the skyline. New York is, finally, its people, that perpetually fresh infusion of rigor, rage, talent and terror that adds ever-new coats of paint to the neighborhoods, and this batch of pictures tries, in 2015, to show the town as it is used, by its daily caretakers. The push. The pull. The gamut of sensations from sky to gutter.

So have a look if you will and weigh these impressions against those you’ve discovered through others or developed within yourself. Taking on a photographic task that can never be finished is either frustrating or freeing, depending on your artistic viewpoint. In the meantime, what a ride.

THAT’S YOUR QUEUE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS CONVENIENT AND SIMPLE AS MANY PANORAMIC APPS AND TECHNIQUES HAVE BECOME OF LATE, there are many ways to accent a wide linear line of photo information within a standard camera frame. With images shot in very large file sizes these days, (even without shooting in RAW), plenty can be cropped from a photograph to produce the illusion of a wide composition with no loss in quality. It’s the pano look without the pano gear, and it’s a pretty interesting way to do exposition on crowds.

I first started noodling with this in an effort to save images that were crammed with too much non-essential information, most of them random streets shots that were a little busy or just lacking a central “point”. One such image was an across-the-street view of the area around the Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. Lots of building detail, lots of wandering tourists, and too much for a coherent story. Lopping off the top two-thirds of the frame gave me just the passing crowd, an ultra-wide illusion which forced the viewer to review the shot the way you’d “read” a panel in a comic strip, from left to right.

Lately, I’ve been looking for a purer version of that crowd, with more space between each person, allowing for a more distinct comparison between individuals. That is, short guy followed by tall woman followed by little kid followed by….you get the idea. Then, last week, I happened upon the ideal situation while shooting randomly through a window that looked out on the 51st street side of New York’s Radio City Music Hall: a long line of folks waiting to pre-purchase event tickets. The space between them and the street rhythm shown by a few out-of-focus passersby was all the composition I needed, so in the editing process I once again aced the top two-thirds of the picture, which had been taken without zoom. A bit of light was lost in shooting through the window, so I added a little color boost and texturizing in Photomatix (not HDR but Tone Compression settings) and there was my pseudo-pano.

It’s a small bit of cropping choreography, but worth trying with your own street shots. As as is the case with many images, you might gain actually strength for your pictures the more ruthlessly you wield the scissors. Some crowd shots benefit by extra context, while others do fine without it. You’ll know what balance you’ll need.

THE JOY OF BEING UNIMPORTANT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE AT LEAST TWO WOMEN IN MY LIFE WHO WORRY if I am sufficiently entertained whenever I am borne along on their ventures into various holy lands of retail. Am I waiting too long? Am I bored at being brought along? Would I like to go somewhere else and rejoin them later at an appointed time and place?

Answers: No to questions 1, 2 and 3…so long as I have my hands on a camera.

I can’t tell you how many forays into shoe emporiums, peeks into vintage stores and rambles through ready-to-wear shops have provided me with photographic material, mainly because no one would miss me if I were to disappear for a bit, or for several days. And, as I catalogue some of the best pickings I’ve plucked from these random wanderings, I find that many of them were made possible by the simple question, “do you mind amusing yourself while I try this on?” Ah, to have no authority or mission! To let everything pale in importance when compared to the eager search for pictures! To be of so little importance that you are let off the leash.

The above image happened because I was walking with my wife on the lower east side of Manhattan but merely as physical accompaniment. She was looking for an address. I was looking for, well, anything, including this young man taking his cig break several stories above the sidewalk. He was nicely positioned between two periods of architecture and centered in the urban zigzag of a fire escape. Had I been on an errand of my own, chances are I would have passed him by. As I was very busy doing nothing at all, I saw him.

Of course, there will be times when gadding about is only gadding about, when you can’t bring one scintilla of wisdom to a scene, when the light miracles don’t reveal themselves. Those are the times when you wish you had pursued that great career as a paper boy, been promoted to head busboy, or ascended to the lofty office of assistant deacon. I’m telling you: shake off that doubt, and celebrate the glorious blessing of being left alone…to imagine, to dream, to leave the nest, to fail, to reach, to be.

Photography is about breaking off with the familiar, with the easy. It’s also having the luck to break off from the pack.