OF CLEARINGS AND COVER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“LOST IN THE WOODS”. “DEEP IN THE FOREST”…conjure your own phrase for the sensation of entering, and being swallowed by, dark, mysterious places. Realms of shadow, primordial laboratories in which both dreams and nightmares are brewed. In other words, sites where photographers can wax poetic. Or crash and burn.

Forested areas are both challenge and opportunity for shooters, since they are seldom subject to the same laws of composition or exposure as subjects shot out in the open. Mastering light in woodsy settings can be a crusade in its own right: details can melt into dark murk or be completely blown out in sudden shafts of sunlight. I have produced more mushy, indecipherable messes with more cameras in more forests than I care to count, in pictures which inadvertently produce more mystery than they reveal, as in “what’s this supposed to be?”

I can come a lot closer to coherence when I work with partial clearings rather than dense woods, working with simpler compositions that suggest the feel of the forest from its near edge rather than its center. Exposure becomes a more streamlined process as well.

Also, since the emphasis in such a shot is on mood rather than detail, even the basics of focus can become, well, negotiable, as seen here. But then, almost anything in the making of a photograph is. Or should be. My point being that, when the taking of a picture fails, it can be because the photographer is trying to execute too many things at once. Eliminating some of those things until the image becomes manageable can be, like walking out of a dark forest, a profound relief.

GOING HALFIES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN A PERFECT WORLD, all our photographs would have their permanent address at the intersection of Flawless Technique Street and Great Message Boulevard. And while some do, magically, make it to this mystical crossroads, many others lose the paper the directions were scribbled on and wind up down some back alley.

Powerful narratives can arrive in perfect packages, sure. But not often and not with any predictability. Often we settle for one half of the ideal or the other. That “going halfies” choice determines what we regard as most important in our favorite images.

I would love to be able to achieve technical perfection every time I’m up to bat, but I’m not religious about raw precision….at least not the way I am about emotional resonance. Every one of you has a pile of pictures which are optically flawless and another pile of pictures that speak to your best intentions. Given an either/or judgement on which of these are your “keepers”, why wouldn’t you always, always choose the images that, regardless of various “flaws”, conveyed your mind and heart?

Light, focus, aperture, even composition are tools, not ends unto themselves, and even the best photographers drop one or another of these techno-balls in some of their best work. But should we seriously disqualify an image merely on technical points? If the answer is yes, then half of the works that we collectively value as great must be stricken from the public record, and photography is merely a recording process, like the operation of a seismograph or any other instrument where precision trumps every other consideration. But if the answer is no, then a picture that fails one or more technical tests can stil be considered valid, so long as it is emotionally true.

I struggle with these choices whenever I produce a shot that has things “wrong” with it, but which is also an authentic register of where my mind was at the time it was snapped. Photos like the one seen here would fail many a judge’s test, depending on who’s doing the judging. It’s too dark. The shutter speed is way too slow, inviting blur. Some of the shadows swallow detail that might just be important. And yet I love this building, these people, this moment. In my defense, I had to decide in an instant whether to even attempt the picture, taken, as it was, from the back seat of an Uber lurching unevenly through the streets of Manhattan. Shooting on full manual, I had to anticipate fast changes in available light, the length of traffic signals, the process of shooting through glass with a filtered lens, and the occasional offensive/defensive maneuvers of the driver. In raw scoring, I just didn’t manage to master all of these variables in a technically perfect manner. And yet..

There has been a lot of talk lately about not letting the Perfect be the enemy of the Good, a phrase which says more about photography in ten words than I’ve said in this entire page. Rule one for shooters: don’t let the flawless be master over the real.

DRINK / SHOOT YOUR FILL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SHOOTING FROM A PROPRIETARY VIEWPOINT is the photographer’s equivalent of being invited to a wedding with an open bar. You try everything. Turns out you don’t really like Singapore Slings? Leave it on a tray and go back for the Jack and Coke.

It really is that simple. If you find yourself with a one-of-a-kind view, assume you’ll never be invited back and hit the subject with everything you’ve got. Change lenses. Up-end your normal method of working. Do something screwy. But do try it all. Hey, you’re on top of Mt. Fuji, right? So it’s not like you’re passing this way again next month. Go for broke.

The Manhattan rooftop from which these samples were shot was a gift, and I knew it. I popped off dozens of frames in every direction with every combination of gear and settingscI could think of, simply because the vantage point would likely never be available to me in the future. Not anytime soon, anyway. One thing that’s always in the back of my mind when shooting in New York is the wonderful look of classic images shot in Kodachrome, the greatest but most temperamental film in history, now gone to that Big Darkroom In The Sky. Kodachrome had amazingly warm color saturation, but, all science-y talk aside, its “look” was probably due in large part to the fact that it was slooooww, just the equivalent of 100 ISO at its speediest. That means that, simply, many of us were underexposing it. By a lot. Anyway, I’m always out to craft my own Kodachromesque Manhattan, and I saw a chance to do so in this particular situation.

The two shots seen here were taken mere seconds apart from each other, both shot with a 24mm prime sporting a circular polarizing filter. The lighter one is f/8 at 1/60 sec., while the darker, more “day is done” image is deliberately underexposed at f/16, 1/160 sec. The combination of the smaller aperture and the filter doubles the intensity of all colors, but sacrifices someinformation in the shadier areas. I leave it to you as to what’s been gained and what’s been lost. The point is that I shot about eight other versions of this scene, erring on the side of too many choices in everything I aimed at that afternoon. Photography is not only apprehending where you are, but understanding just how briefly you’ll be there.

But, hey, it’s possible I’ll get a repeat invitation to this particular roof. Then again, I spilled my Jack and Coke all over the hostess on my way out, so you never can tell.

ARTIFACTS

SOME OF THE BEST PHOTOGRAPHS come riding in on the backs of the scrawniness stories, like Don Quixote limping into town astride Rocinante. To be sure, images are evidence, proof of a kind of a person’s various truths or journeys in life. But there are times when that evidence is scant, hidden, confined to the dimensions of a bone, the chip of a cup, The Dress She Loved.

Or a tool.

Like the camera itself, the tool is a device designed to work its wielder’s will. Case in point: the instrument at left, a punch for cutting holes into leather, a device which has no other official function than to execute the hand movements of the shoemaker who once owned it. A thing created to dumbly create other things.

But now, absent its master, it is also testimony.

With the shoemaker gone, the tool becomes a partial proof of his life, a defining characteristic of the way he made his living. It’s also a kind of miniature history of things in general, a living demonstration that, literally, “they don’t make ’em (or him) like that anymore”. In photographing the things people carried, which now must speak for them, I use the sharpest, most accurate lenses I can, using nothing but opaque backgrounds and soft window light, seeking the registration of every speck of patina, rust, discoloration or personalization available. For example, I love the worn fragment of leather glued to the left grip of the punch. I know, historically, that this particular tool was not originally made with any such pad or cushion, and so it had to have been the very human creation of its owner, an attempt to add a smidgeon of comfort to what must have seemed an endlessly repeating task.

I have photographed many artifacts from people I either knew too little or too briefly, from military decorations to cameras to scientific instruments to pocket watches. All reveal quiet stories about the vital beings who once thought of their quotidian uses as the stuff of forever. Now, weilding my own tool of trade, I can extend tiny bits of those forevers into a few more precious days.

HAPPY-EN-STANCE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S FAIR TO SAY that photographers are occasionally the worst possible judges of what will save or spoil a picture. Try as we may to judiciously assemble the perfect composition, there are random forces afoot in the cosmos that make our vaunted “concepts” look like nothing more than lucky guesses. And that’s just the images that actually worked out.

All great public places have within them common spaces in which the shooter can safely trust to such luck, areas where the general cross-traffic of humanity guarantees at least a fatter crop of opportunity for happy marriages between passersby and props. At Boston’s elegant Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the surrounding walls of the central court are the main public collecting point, with hundreds of visitors framed daily by the arched windows and the architectural splendor of a re-imagined 15th-century Venetian palace. The couple seen here are but one of many pairings observable in a typical day.

The pair just happens to come ready-made, with enough decent luck assembled in one frame for almost anyone to come away with a half-decent picture. The size contrast between the man and the woman, their face-to-face gaze, their balanced location in the middle arch of the window, and their harmony with the overall verticality of the frame seem to say “mission accomplished”. I don’t need to know their agenda: they could be reciting lines of Gibrhan to each other or discussing mortgage rates: visually, it doesn’t matter. At the last instant, however, the seated woman, in shadow just right of them, presents some mystery. Is she extraneous, i.e., a spoiler, or does she provide a subplot? In short, story-wise, do I need her?

I decide that I do. Just as it’s uncertain what the couple is discussing, it’s impossible to know if she’s overhearing something intimate and juicy, or just sitting taking a rest. And I like leaving all those questions open, so, in the picture she stays. Thus, what you see here is exactly one out of one frame(s) taken for the hell of it. Nothing was changed in post-production except a conversion to monochrome. Turns out that even the possibility of budding romance can’t survive the distraction of Mrs. Gardner’s amazing legacy seen in full color, and the mystery woman is even more tantalizing in B&W. Easy call.

As we said at the beginning, working with my own formal rules of composition, I could easily have concluded that my picture would be “ruined” by my shadowy extra. And, I believe now, I would have been wrong. As photographers, we try to look out for our own good, but may actually know next to nothing about what that truly is.

And then the fun begins….

THE NIGHT OF THREE MIRACLES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I NEARLY MISSED OUT. Early last evening, my wife spied an internet article on the imminent arrival of what could only be called an astronomical trifecta, a moon which, for the first time since 1866 would qualify as a wow in three distinct cosmological categories, as an oversized, or “super” moon, a lunar eclipse, and an orange-red “blood moon”, seen to fullest effect in America’s western states.

Hey, I live in one of those……

I’ll be out in the driveway, honey. For, oh, I dunno, a while….

The first, or supermoon phase of the trifecta I had experienced several times before: lunar light strong enough to read by, with time exposures of three minutes, or even less, retrieving a full range of natural color in everything from orange roof tiles to blue skies…..hours after sunset. That’s what you see up top. A manual 35mm lens (the shutter remote won’t work with autofocus, anyway), an aperture of f/5.6 for fair depth of field, and the flat top of a mailbox for a makeshift tripod and, bingo, it looks like early dusk instead of 10pm.

The second phase had to wait for the early hours of this morning, at which time various web accounts predicted the earth would interpose itself perfectly between the sun and the moon, causing a crescent-shaped shadow to crawl up the orb from the bottom, giving it a deep red-orange glow beginning at around 6:15am (which in an Arizona winter, is still pre-dawn).

As with dusk the night before, the sky, appearing black to the naked eye, would reveal a lot of blue in a time-exposure taken just before sun-up, so I elected to make the moon a small part of an overall composition instead of an isolated solo superstar. I have plenty of textured zoom shots of the moon: what interests me in such special cases is the light and hue of it in context. In this case, fifteen seconds wide open at f/2 was enough to get the major bits to register. Still too lazy to find my tripod, I subbed a folding stepladder. A matter of five minutes’ work.

I certainly plan to be around in 2037 when another “Super Blue Moon/ Bloodmoon/Lunar Eclipse appears, but in years past I also have planned to retain all my hair and teeth, and the jury’s still out on that particular quest. In the meantime, all of life is littered with wonder, so, as the old pop song sez, pick up your hat, lock up your flat, get out, get under the moon…

ALL ON ME

PHOTOGRAPHERS ARE FREQUENTLY ASKED to define a “bad” picture, or, more specifically, the worst picture they themselves ever shot. The question is a bit of a logic trap, though, since it typically tricks us into naming something that failed because the subject was moribund, or because we mis-read the light, the aperture, the composition. The trap further reasons that, if you have checked off all those boxes, you should end up with a great picture.

But all of that is bug wash. What makes a picture bad is when you were not ready to take it….. but you took it anyway.

Sometimes the problem is ignorance: you simply aren’t old or wise enough to know what to do with the subject. Other times, you have substantial barriers between you and an effective story, but you try to drill past what you can’t fix. And, you can no doubt add your own list of things that, ahead of the shutter click, should scream, “not now”. Try to make the picture before either the conditions or you (usually you) are right, and you lose. Just as I lost, in great big neon letters, with the mess you at above left.

In 2016, I visited the Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, a venerable colonial-era home which sits right next to the small footbridge that served as the site of the first major battle of the Revolutionary War. What excited me most, however, was that it had served as a temporary home for the young Ralph Waldo Emerson, and that he had written Nature, the first of his great works, while living there. And to really put the cherry on the sundae, the house still contains the small writing desk he used to do it.

The house is lit only with indirect window light during the day, but with a fast prime lens and a decent eye, there’s more than enough soft illumination to work with to produce decent results (see left). In fact, just before my tour was to head into the room containing the desk, I had already harvested quite a few usable shots…so many, in fact, that I was getting teased by the others in the group…the usual “oh, another picture?” stuff. Uncharacteristically, I began to worry about whether I was holding everyone else up, and thus started to hurry myself, to shoot not as I intended, but in deference to what I thought others would like. By the time I got to Emerson’s chair, the light, my lens, even my own experience were all useless to me….because I wasn’t ready to shoot….but did anyway.

The house is lit only with indirect window light during the day, but with a fast prime lens and a decent eye, there’s more than enough soft illumination to work with to produce decent results (see left). In fact, just before my tour was to head into the room containing the desk, I had already harvested quite a few usable shots…so many, in fact, that I was getting teased by the others in the group…the usual “oh, another picture?” stuff. Uncharacteristically, I began to worry about whether I was holding everyone else up, and thus started to hurry myself, to shoot not as I intended, but in deference to what I thought others would like. By the time I got to Emerson’s chair, the light, my lens, even my own experience were all useless to me….because I wasn’t ready to shoot….but did anyway.

And so you behold the unholy mess that resulted: lousy contrast, uneven exposure, muddy texture (is the chair made out of wood or Play-Doh?), tons of noise, indifferent angle, and, oh yeah, garbage focus. Worse yet, the psyche I’d put upon myself was so severe that I didn’t slow down for a more considered re-do. No, I rejoined the group like a polite little camper, and left without what I had come for.

And that is all on me, and thus an important entry in The Normal Eye, an ongoing chronicle which is designed to emphasize personal choice and responsibility in photography, versus just hoping well-designed machines will compensate for our lack of concept or intention. This is not easy. This is ha It’s no fun realizing that what went wrong with an image was us.

But it’s a valuable thing to own. And to act upon.

PALING BY COMPARISON

A good sunset to the naked eye, but rendered very blue by the camera’s auto white balance setting.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GIVEN HOW MANY PICTURES YOU NEED TO SHOOT, over a lifetime, to develop the kind of eye that will deliver more keepers more often, you have to make peace with the taking of many, many images that do not, strictly speaking, “matter”. They’re either uninteresting or indifferently executed or mere technical exercises that don’t emotionally stick. However, that does not mean they are a waste of time, since the practice meter is running whether you’re making magic or mud. And with some mindfulness, you can get into the habit of harvesting something worth knowing, even in the most mundane of shoots.

Just straying from your standard procedures in very small particulars can show you new options for shaping or salvaging a photo. In the two comparison shots seen here, there is only one thing that distinguishes the first picture from the second one; the camera’s white balance setting.

I just am not a fan of shooting on auto modes or default settings, for the simple reason that they are designed to produce average, not extraordinary pictures. They prevent us from making a total dog’s breakfast of an image, but they also deny everyone choice except, weirdly, the camera.

On the particular shooting expedition seen here, I was seeing a warm, full-on golden hour of pre-sunset, the rich oranges and browns visible even in shade. However, the camera’s auto white balance, which reads the temperature of light to “see” white the way we do, was delivering a lot of blue. The simple switch to a “shade” setting rendered even the deepest shadows as warmly as my eyes did.

The point is, this image was part of an uneventful afternoon’s casual stroll, yielding nothing in the way of “legacy”-level work. It was simple journeyman practice. What makes such tiny technical decisions valuable is how instinctual they can become when repeated over thousands of pictures, how available they become as tools when the picture does matter. Pictures come when they’re ready. With luck, building on the lessons from all those “nothing” pictures mean you’ll be ready as well.

OUT OF THE DEPTHS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I MAY BE OVER-COMPENSATING A BIT OF LATE, making the kind of correction a newly-minted driver makes when he steers too far in one direction, then steers just as radically in the other. Five years ago, my photography was caught up in the feverish rescue of detail from dark places. I embraced HDR (High Dynamic Range) imaging as a way to illuminate every part of a frame, fearing that important information was being lost in the shadows. I was consumed with delivering what the camera was inefficient at seeing, and spent a lot of time making exposures “balanced”, making sure everything in them was viewable.

These days, by contrast, I seem to be all about the dark, or least its creative use as an element in more and more pictures. Darkness is a lot more subtle than that which is visible, as it merely hints, rather than states, information. I see darkness now the way that graphic artists might have several centuries ago, when the recording medium might be a treated paper that was all colored, or all dark, and the lighter values of a composition might be drawn onto that medium with white paint or chalk.

With such methods, early drawings by Michelangelo and others saw darkness as the start point, with so-called “positive” values sort of extracted from it. In photographic terms, I seem to be taking the same approach to a lot of pictures recently, beginning with a sea of undefined murk and pulling just enough information out of it to create a composition. Whereas, just a few years ago, I was summoning forth every hobnail of detail possible out of a frame, now I am mining the very minimum. I want the unanswered questions posed by darkness to remain largely unanswered. Too much detail means too much distraction.

The practitioners of chiaroscuro (artists like Rembrandt and Reubens) also started with a dark canvas but used light, usually from a single source such as a window, to model their subjects, to give them a three-dimensional quality. I sometimes do that too, but mostly, I am asking the viewer to enter into a partnership with me. The terms: I’ll show you part of the story, and you supply the rest.

Where will I be in the next five years? I’m totally in the dark.

ON THE JOB

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST EXHAUSTIVE portrait projects in the history of photography was August Sander’s Face Of Our Time, a collection from the 1920’s of sixty formal portraits of German tradesmen of every class and social station, each shown with the tools or uniforms unique to his chosen profession. Sanders photographed his subjects as documents, without any hint of commentary or irony. The story in their pictures was, simply, the visual record of their place in society and, eventually, as cultural bookmarks.

Since Sander’s eloquent, if clinical work, similar photo essays have taken on the same subject with a little more warmth, notably Irving Penn’s Small Trades portrait series from the early 1950’s. Like Sander, however, Penn also shot his images in the controlled environment of the studio. In my own work, I truly feel that it’s important to capture ordinary workers in their native working environment, framed by everything that defines a typical day for them, not merely a few symbolic tools, such as a bricklayer’s trowel or a butcher’s cleaver. I also think such portraits should be unposed candids, with the photographer posing as little distraction as possible.

I really like the formal look of a studio portrait, but it doesn’t lend itself to reportage, as it’s really an artificial construct….a version of reality. So called “worker” portraits need room to breathe, to be un-self-conscious. And, at least for me, that means getting them back on the street.

POST STARTS NOW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE POST–PROCESSING REVOLUTION wrought by the introduction of Photoshop in 1988 has so profoundly influenced the act of picture-making that many shooters think of the program as half of a complete two-step process of photography. In Step One, you shoot the image. In Step Two, you fix it.

However, being conversant with more of the menu options built in to nearly every level of camera in use today can mean solving most “post” dilemmas without resorting to Photoshop’s full suite of solutions. Just as you change lenses less the more you understand what lenses can be stretched to achieve, you can avoid the extra step of computer-based tweaking the more you understand what’s already available while your subject, your shooting conditions and your mental presence are all in play. Some would argue that such adjustments would be more finely attenuated working with a RAW file in Photoshop than by fixing flaws in-camera with a JPEG, and you have to decide where you come down in that debate.

Let’s take color as one example. A great many photographs with off-kilter values are corrected in Photoshoppish apps, yet can be quite satisfactorily fixed in-camera. White balance settings allow you to pre-program a number of light temperature pre-sets that make your camera “see” colors as if they are occurring in sunshine, shade, or a variety of artificial light sources. But even if you shoot everything on the “auto” white balance setting and get the wrong colors occasionally, there is still a way to repair the damage without resorting to Photoshop. What Nikon and Canon both call color balance allows fairly fine-tuned adjustments to get the hues to look either (a) more like you saw it, or (b) the way you wish it had looked.

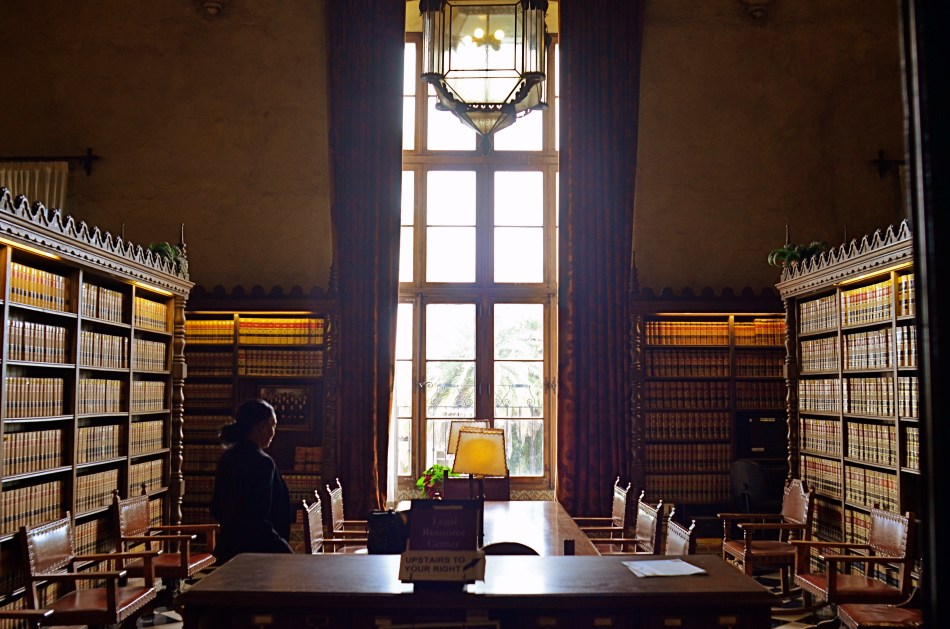

The shot at top, adjusted with Nikon’s color balance option, produced the warmer look in the bookshelves that would have resulted if the light coming through the window had been warmer. In the original image, taken with an auto white balance setting, the camera, far from “guessing wrong”, actually recorded the room light as it appeared in reality, since the sky was severely cloudy and was a little blue in cast. However, with the in-camera color balance tweak, no Photoshop intervention was required. Moreover, I could check my work while in the moment, a handy thing, since tours were moving in and out of the room all day, meaning that, if I wanted to shoot the room (nearly) empty, I had to work fast.

Digital photography’s original bragging point over film was the ability to shoot, fix, and shoot again rather than rely on the darkroom to rescue tragically few of our miscalculations. Working our in-camera menus for all they’re worth helps deliver on that promise.

IRVING’S CURTAIN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

BY THE TIME IRVING PENN (1917–2008) WAS ESTABLISHED as a portraitist without equal for Vogue magazine, he had chalked off clear parameters for his style. Natural over artificial light: large format, high-resolution monochromes: a patient talent for extracting the essence of even the most reluctant subject: and an almost lucky-charm devotion to the worn and stained curtain he would use, almost exclusively, as his backdrop for the length and breadth of his legendary career.

Salvaging the curtain from a Paris theatre in 1950, Penn used it as the great equalizer in all his portrait work, staging everything from Picasso’s puckish gaze to Audrey Hepburn’s gamine charm in front of its collection of stains, spills and discolorations. The curtain was as essential to a Penn shoot as the great man’s lenses, and where he went, from remote African villages to literary salons, it went also. And finally, eight years after his death, it traveled one more time to New York, for a supporting role in an Instagram near you.

As part of the Metropolitan Museum Of Art’s centennial celebration of Penn’s work for 2017, the curtain was installed in a room chocked with shots of the famous people with which it had co-starred. Studio-style, it was mounted on a curved panel to avoid hot spots from glare, and visitors were invited to pose themselves in front of it, fore-lit by a well-placed fashion light. The message was seductively mis-leading. If the cloth is magic, maybe it’s transferable! Maybe it is that black crow’s feather that makes Dumbo fly…..

The Met’s true genius in installing this Penn-it-yourself feature in its exhibit became obvious once you took the bait. That is, there’s nothing better to teach you that his work was great than allowing you to take very bad pictures under some of the same circumstances. I certainly got the point after clicking off a seriously flawed candid of my wife, seen here. I mean, other than blowing the focus, the metering, and the placement of light and shadow, the shot’s perfect, right?

Of course, the Penn curtain challenge had a kind of theme-park appeal, sort of like when you stick your face through a hole in the back of a cartoon cutout at Coney Island to have your picture taken as a “strongman”…and just about as convincing. Because art isn’t gear: genius isn’t mere tools. And you can’t be Rembrandt just by picking up Rembrandt’s brush.

FAKING YESTERDAY (AND LOVING IT)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS ARE POWERFUL ALLIES when it comes to wish fulfillment. One of the medium’s first great artists, Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) not only preserved the faces of Charles Darwin, Alfred Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning for posterity, but also went the extra step into fantasy by draping her subjects in historical costumes and posing them in illustrations from Shakespeare and Arthurian legend. Her stars masqueraded as legends, their features made dreamy and ethereal with her soft, long exposures on collodion-coated glass plates.

Everyone deserves at least one such photo fantasy, the chance to effectively leap into a treasured era while also creating the look that would have been common in that time. For a kid in baby-boom Ohio, daydreaming about standing up in front of a world-class orchestra, a kid who never played air guitar but who exhausted himself playing “air baton”, my photographic era of choice was that of Columbia Masterworks’ 30th Street recording studio in the Manhattan of the early 1960’s.

At the insistence of the label’s classical producer Goddard Lieberson, chief photographer Don Hunstein shot the greats not in starched, formal portraits, but in the very act of creation, immortalizing maestros from Leonard Bernstein and Pierre Boulez to George Szell and Igor Stravinsky. In terms of the “feel” of the images, most photo illustrations for album jackets from the period were still in black-and-white, lending Hunstein’s shots a gritty realism, as did the slower, higher-grain film emulsions and softer portrait lenses of the time.

Enter my self-generated conductor fantasy, shooting myself with a remote shutter release in a nearly dark room, just about half an hour after sunset at 1/40 of a second to allow me to hold a fake “caught in the action” pose with just a small amount of manually tweaked de-focusing for softness at f/4 and an ISO of 1250 to simulate the old Kodak Tri-X grain.

Vain beyond belief? You bet. More fun than my five best Halloweens combined? Indeed. “Alright everyone. Let’s take it from bar 124…”

TWILIGHT TIME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE STRUGGLED OVER A LIFETIME to tell photographic stories with as few elements as possible. It’s not unlike confining your culinary craft to four-ingredient recipes, assuming you can actually generate something edible from such basic tools. The idea, after all, is whether they’ll eat what you’ve cooked.

With images, I’ve had to learn (and re-learn) just how easy it is to lard extra slop onto a picture, how effortlessly you can complicate it with surplus distractions, props, people, and general clutter. Streamlining the visual language of a picture takes a lot of practice. More masterpieces are cropped to perfection than conceived that way.

The super-salesman Bruce Barton once said that the most important things in life can be reduced to a single word: hope, love, heart, home, family, etc. And so it is with photographs: images gain narrative power when you learn to stop sending audiences scampering around inside the frame, chasing competing story lines. Some of my favorite pictures are not really stories at all, but single-topic expressions of feeling. You can merely relate a sensation to viewers, at which point they themselves will supply the story.

As an example, the above image supplies no storyline, nor was it meant to. The only reason for the photo is the golden light of a Seattle sunset threading its way through the darkening city streets, and I have decided that, for this particular picture, that’s enough. I have even darkened the frame to amp up the golds and minimize building detail, which can tend to “un-sell” the effect. And yet, as simple as this picture is, I’m pretty sure I could not have taken it (or perhaps might not even have attempted it) as a younger man. I hope I live long enough to teach myself the potential openness that can evolve in a picture if the shooter will Just. Stop. Talking.

YOU AND YOUR BRIGHT IDEAS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE SELF–EDUCATION PROCESS INHERENT in photography is perpetual: that is, the lesson-learning doesn’t “clock out” merely because a given task is completed, but flows equally during the in-between moments, the spaces outside of,or adjacent to, the big ideas and big projects. Down time need not be wasted time.

Often it’s because the pressure of delivering on a deadline is absent that we relax into a more open frame of mind as regards experimentation. You find something because you’re not looking for it.

One such area for me is lighting. I seldom use flash or formal studio lights, so I obsess over cheap, mobile, and flexible means of either maximizing natural light or adding artificial illumination in some simple fashion. This isn’t just about making an object seem plausibly lit, or, if you like, “real: it’s also about choosing or sculpting lighting schemes, making something look like I want it to.

Small, powerful LEDs have really given me the chance to fill spare moments cranking out a wide array of experimental shots in a limited space with little or no prep, producing shaping light from every conceivable angle. I just lock the camera down on a tripod, make some simple arrangement on a table top, and shoot dozens of frames with different directional sweeps of the light, usually over the space of a time exposure of around a half a minute. I can move the light in any pattern, either by holding it static or tracking high/low, left/right, etc.

Frequently this activity does not result in a so-called “keeper” image. Such spare-time experiments are about process, not product. The real pay-off comes somewhere further down the road, when you have need of a skill that you developed over several days when you had.. nothing to do.

WHEN AND HOW

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I photograph late in the day, the time Rembrandt favored for painting, so that the subtlest tones surface. ———Marie Cosindas

ONE OF THE GREATEST SIDE EFFECTS OF MY HAVING LIVED IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST over the past eighteen years has been its impact on how I harness light in my photography. The word harness conjures the act of getting a bit and bridle on a wild stallion, and so is extremely apt in reference to how you have to manage and predict illumination here in the land of So Much Damn Sun. It’s not enough here to decide what or how to shoot. You must factor in the When as well.

To see this idea in stark terms, study the work of photogs who have shot all day long from a stationary position along the rim of the Grand Canyon. The hourly, and sometimes minute-to-minute shift of shadows and tones illustrates what variety you can achieve in the outcome of a picture, if you consciously factor in the time of day. After a while, you can glance at a subject or site and predict pretty accurately how light will paint it at different times, meaning that many a session can produce a wild variance in results.

I scouted this location when sunlight was coming from the front of the court, then returned in the late afternoon to shoot it with the sun entering from the back to snag the shadow pattern I preferred.

The late photographer Marie Cosindas, whose miraculous early-1960’s work with the then-new Polacolor film helped change the world’s attitude toward color imaging, didn’t just load her film into a standard Polaroid instant camera. She shot it in her large format Linhof, experimenting with exposure times, filters and development techniques, and, above all, with the careful selection of natural light. She didn’t just wait for her subject; she waited on the exact light that would make it, and all its colors, sing. As a result, the art world began to rethink its opinion about color just being for advertising, or as somehow less “real” than black & white.

In my own work, I take the time, whenever feasible, to “case” locations a while before I shoot them, taking note over days, even weeks, to see what light does to them at specific times of day. As I mentioned, the West suffers from an overabundance of light, mostly the harsh, tone-bleaching kind that is the enemy of warm tone. In the above image, I scouted the location in the early morning, when the eastern sun was drenching the front end of the court, but waited about eight hours to return and get the precise projection of shadow grids that only occurred once the sun was in its western descent, about two hours before dusk. My test shots from the morning told me that the picture I wanted would simply not exist until ’round about suppertime. And that’s when I stole my moment.

There are three legs to the basic photographic tripod: What, How, and When. Over the years, paying greatest attention to that third leg has often given me one to stand on.

A NEW TAKE ON OPAQUE

Canyon Echoes (2015). A circular polarizing filter helps the building across the street to be more vividly captured in the glass grids.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY’S REVOLUTION IN URBAN ARCHITECTURE produced a radical re-imagining of the physical science of erecting buildings, along with a remarkable shift in what those buildings should look like. An extreme shift in outward design can be tracked from the ornate Greco-Roman and Gothic textures of the Woolworth Building at century’s start to the stark, spare rectilinear boxes of the ’40’s and 50’s, as we jetted from doric columns, oak clusters and gargoyles to the completely un-ornamented glass boxes that we associate with, say, the Pan Am or United Nations buildings at the other end. That changed the way we live, and likewise transformed the way we photo-document our cities.

And, whatever your opinion of what came to be called the “International Style”, the boxes today co-exist with their more decorous ancestors, a contrasting mix which creates amazing opportunities for abstraction. The collision of the two periods creates an endless shuffling of visual cues, with all that glass and terra cotta dueling for dominance in our compositions. And therein lies a tip: one tool which you may find of enduring value in shooting in these situations is a circular polarizing filter, which can help you create a wide variety of effects…quickly, and on the cheap.

People in sun-soaked sectors of the world mostly use the CPL to deepen the blue in overly-bright skies, but the filter’s ability to cut glare on reflective surfaces like water and glass can also be dramatic, and that’s how I use it in urban settings. I’ve come to love the idea of a sheer wall of glass in one building being stamped with all the details of the building directly across the street (over my shoulder). Twisting the upper ring of the CPL dials in the degree of glare you want in your image, allowing you to see none, some, or all of your neighboring structure in the glass in front of you. One caution: the filter also deepens color and can rob you of up to a stop of light, so you want to plan your exposures more carefully, something that’s done easier shooting on full manual.

The dominant idea of design in the International Style was to eschew detail and ornament to as great a degree as possible. That resulted in a lot of very boring exteriors as a vast crop of largely faceless boxes shot off the assembly line. However, using their sheer screens of glass as a vibrant kind of video display for the neighborhoods around them actually breathes a little life into them, and the circular polarizing filter gives you a remarkable amount of control over that process.

THE OTHER SIDE OF SOFT

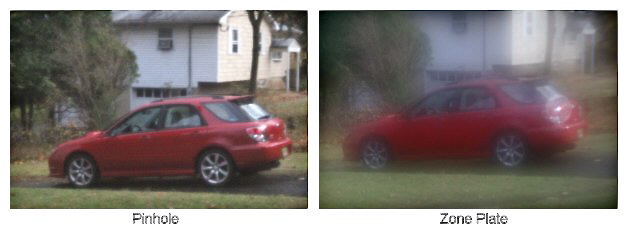

A side-by-side comparison of the two main systems of “lensless” photography, the pinhole and the zoneplate.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS (AND HUMANS IN GENERAL) ARE CONTRARY. Tell them they’re forever stuck with a bones-basic camera and they’ll spend every night and weekend either trying to devise a more sophisticated device or work three jobs so they can buy one. And the obverse is also true: present shooters with an infinite number of hi-tech choices designed to deliver unprecedented precision, and they’ll perversely start to pine for the “lost innocence” or “authenticity of the bare-bones rig.

What else can account for the recent surge in lensless photography, and the creation of images with cameras that are more technically handicapped than even one’s first point-and-shoot? Of course, the very first image capturing was done without a lens, with the ancient Greeks creating pictures on the inside back panel of a camera obscura box, using nothing but a small pinhole to generate a dim, soft-focused image of the chosen subject. The early nineteenth century replaced the hole with custom-designed glass optics, and photography moved quickly from a scientific experiment to a global rage.

But, of course, for photographers, no part of their art’s history is really “past”, and so we now see a small explosion of new pinhole devices for both film-based and digital cameras, from specially manufactured pinhole body caps (used in place of a lens) to cardboard kits available as DIY projects to recently dedicated pinhole plug-in optics for the Lensbaby series of lenses. The idea remains the same: small apertures, virtually infinite depth of field, soft focus, and looong exposures.

The other variable in this craze is the popularity of zoneplates, which, unlike the refracted light in a pinhole, works with more scattered diffracted light, creating a halo glow in the high contrast areas of subjects, as if the soft-focus is also being viewed through a gauzy haze. A zoneplate is really like a bulls-eye target, a plate where both opaque and transparent “rings” combine to disperse light widely, delivering a dreamier look than that seen in a pinhole image. The other big difference is that a zoneplate has a much larger light gathering area and a wider aperture, so while a pinhole opening might equate to a stop as small as f/177, the zoneplate could be as wide as, say, f/19, making handheld exposures (and visualizing through a viewfinder) at least feasible, if tricky.

Of course, both kinds of lensless imaging are extremely soft, rendering a precise depiction of your subjects impossible. However, if light patterns, shapes, and mood outweigh the importance of sharpness for a certain kind of picture, then pinholes and zoneplates are cheap, fairly easy to master (you don’t have much control, anyway), and a little bit like stepping back in time.

It’s contrary….but ain’t we all.

FROM A DARK PLACE

A fifteen-second “light painting” exposure with the product illuminated in a dark room with a hand-held LED.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE STANDARD RECIPE FOR A PHOTOGRAPHIC “PRODUCT SHOT” is rooted in the formal studio lighting set-up. Regardless of whether you’re trying to create an idealized picture of a bottle of soda or a grand piano, the traditional approach is to set up a careful balance of artificial lights, then measure and meter until the object is lit wonderfully from every angle. It’s a system honored by time and tradition, with millions of magazine ads and commercials to attest to its appeal.

Which is fine, except I just happen to find it boring.

Instead of starting with a fully lit room and tweaking towards the ideal, I prefer, with the technique known as light writing, to start at the opposite end of the equation…with a totally dark room, the object in question, and a small, handheld LED, using each shot to light various contours of the object and comparing the results over several dozen frames. Instead of instantaneous exposures, I hold my lens open for as long as it takes for me to move my little torch into place, click on for several seconds at a time, then click off, re-position, and apply lighting to another surface on the object, repeating until I use a remote to close the shutter for good. Results vary wildly from frame to frame, and there is a lot of experimentation to get the look I want, simply because, well, I have no idea what that is when I start.

I may begin by imagining the object as being lit from the side, then try a few takes where the light source comes from above, or even behind. Unlike a traditional studio lighting scheme, light painting allows me to break the rules of nature completely, creating light patterns that could never be achieved in nature. I can spend several seconds arching the LED from one side to another, like a rapidly crossing sun, with the final image bearing every trace of where I’ve tracked over a long exposure.

If I change my mind about what to illuminate in the first ten seconds, for example, I can just adjust it in the next ten. I just re-position the lamp and either augment or erase what’s been stored in the camera in the moments prior. Most importantly, it gives me an infinite number of choices for showcasing the object, settling for a fairly realistic depiction or an utter fantasy or something in between. Comparing the two examples shown here of a series on a whiskey bottle shows how even minute variations in the application of the light give the object a distinctly different identity. And with light painting, the shooter exercises much finer control than is possible with even the best studio set-up….and at a fraction of the cost.

Whether you’re molding an image from a room full of lights or building illumination beam by beam in a darkened room, the whole idea is control. Light painting generates a lot of randomness, and requires a patient eye, but the sheer variety of interpretations it gives you can teach you a lot about the infinitesimal things that can mold a picture, bring more of them under your command.

BRIGHTER IS BETTER

By MICHAEL PERKINS

JUST BECAUSE SOMETHING IS GLIB OR SIMPLE doesn’t mean it’s not true. We tire of people’s pet platitudes because saying things like “get a good night’s sleep” or “honesty is the best policy” seems too easy, as if the wisdom contained in these time-worn axioms must have dried up years ago. So when I tell you something extremely “well, duh!” about photography, it won’t sound wise or profound. It will sound like something any simpleton knows. Obvious. Goes without saying. And yet..

So, here’s my one immutable truth about making pictures:

Get enough light, and you will have solved 99% of any problems that bedevil your photos.

There’ll be a brief pause here for the crowd to collectively roll its eyes.

And before we proceed further, I’m speaking primarily of natural, organic, comes-through-the-window-like-God’s-gift-to-the-world light. Most of what you do with artificial light has to do with compensating and correcting for the fundamental wrongness of the stuff. Yes, I know you have an incredible flash set-up. I don’t care.

Buy the most voraciously light–hungry lenses you can afford.

Light is the only factor in photography that determines the efficacy of every other factor. Every major advancement in the design of lenses, recording media, and camera mechanics has been made for the sole purpose of gathering and utilizing more of it. Light alone can control how a subject is modeled, highlighted, presented. Get enough of it, and you shoot faster and simpler. Learn to shape it and you also learn how to create drama, to compose, to characterize things in precisely the way your mind has visualized them.

Light controls texture. It makes a shot either muted or loud. It can create the sensation of any moment of the day or night. It directs the eye. It makes bad lenses better and good lenses great. And, speaking of lenses, the best money you can spend on any lens, anywhere, is on how fast, how light-hungry it is. All other functions of high-tech optics aren’t worth a bucket of spit if the things can’t deliver lots of light in a hurry. Forget about chromatic aberration, vignetting and all the other headaches associated with glass: get enough light and you’re halfway home.

Most importantly, light is the only element in photography that is literally its own subject. A wonderful image can be of light, about light, because of light. So before you get good at anything else in the making of pictures, learn to gather light efficiently, mold it to your will, and serve it. Every other boat in your optical harbor will be lifted in the process.

Share this:

March 12, 2018 | Categories: Available Light, Commentary, Lenses | Tags: Fast lenses, iso | 1 Comment