DESIGN FOR LIVING

A view into the courtyard of the David Wright House, Frank Lloyd Wright’s gift to his son, built in Phoenix, Arizona in 1950 and now being prepped for complete restoration. The detached guest house and Camelback Mountain are in the distance.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT IT WAS, the final residential design completed by the late Frank Lloyd Wright, mysteriously unsung in every major study of his late work and absent from nearly every retrospective on the cantankerous colossus of twentieth-century architecture. The house, designed for his son David in the Arcadia neighborhood of central Phoenix, Arizona, rose from the desert in 1950 and almost immediately faded from popular view, staying under the radar less than a mile from Camelback Mountain, the sight of which dictated the site of the home, in one of Wright’s most dramatic examples of organic architecture.

And now, just a few years after since daughter-in-law Gladys Wright’s death at the age of 104 and a blink of time since an interim owner first threatened the place with demolition, it is, in 2016, about to sink back from view once more, as the benevolent millionaire who saved it confers with various local factions on the best route to its complete restoration. Tours, which, for the past year have allowed visitors from around the world to walk through what Wright called a solar hemicycle design, his recipe for “how to live in the southwest”, will be suspended. 3-D laser scans will be studied to see where the house’s sixty-five year old foundations need to be fortified and repaired. And, for a time, this remarkably unique dwelling will again be beyond the reach of the camera.

Since The Normal Eye began, we have occasionally mounted photo essay pages featuring singular places, sites too special to be addressed in one or two images. The most recent of these was a tour of author Edith Wharton’s home, The Mount, in Massachusetts. And today, we’ve added a new tab at the top of the blog titled Wright Thinking, with select photos of the David Wright home and its detached guest house, in an attempt to remind people that this hidden treasure does, indeed, survive in the American West.

The essay format seem appropriate because the Wright home is difficult house to convey in just a single photograph, rising from the desert floor in a continuous circular ramp that climbs to the house proper, a 2000 square-foot crescent of rooms mounted on concrete piers and looking north to Camelback Mountain with a window array that presents a view arc of over 200 degrees. Within and without are Wright’s signature components: dramatic furniture design; innovative use of humble materials, from linoleum to concrete; a visionary use of solar energy; and the most Wright of Wright ideas, the organic credo that the site comes first, the house second, and never the other way around.

So thumb through our impromptu Wright family album and visit the house’s wonderful website at www.davidwrighthouse.org to keep apprised of the next sighting of one of the master’s final bows.

YESTER-ESSENTIALS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE MOST REMARKABLE POP CULTURE TRENDS OF THE PAST FEW YEARS has been the improbable reemergence of the vinyl LP, inching its way back onto shelves in edgy fashion boutiques and chain stores alike along with an entire battery of support materials: preeners, cleaners, racks, boxes, even the iconic hippie fruit crate, along with a new generation of high-and-low tech turntables and speakers. It’s fun to watch the emotional re-run that people of, ahem, a certain age will experience as we recall a world that used to be divided into Side One and Side Two.

However, we’ re missing out on a very important part of all that lore. The humble 45 rpm record.

Party On, Garth: A pseudo-HDR made with two copies of the same starter exposure, blended in Photomatix.

Singles were the dominant format for record sales from the beginning of rock to the mid-’70’s, with marketing of pop tunes aimed squarely at the middle bulge of the Baby Boom, a flood of teens armed with disposable cash but consuming their music mostly two songs (A-side, B-side), or about a dollar’s worth, at a time. Eventually, a new crop of college students embraced the LP for its long-form story-telling potential, graduating from singles like Love Me Do to albums like Sergeant Pepper.

Photographically, the remains of all those singles-fed slumber parties and sock hops tell a strong story in the tattered textures of kid’s objects that, like action figures and train sets, were loved to death and treasured all the more because of their imperfections. In the above 45 carrier (party in a box!), half the visual story is told in the wear and tear that is hard-wired into analog. The battered box sings a song all its own.

For this shot, I took a single exposure, side-lit with bright but soft window light, then made a dupe of it, one copy tweaked to near-underexposure, the other to uber-brightness. The two were then made into a fake HDR in Photomatix, which is, above all, a great detail enhancer. Since the shot was done at f/5.6, the whole box is sharp, giving the software plenty to chew on. A few minor changes in contrast to amp up the differences in color along the faded box pattern, and presto, the golden age of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

Photography is about recording change, halting decay in its tracks for a moment….preservation, if you will. The new flawless vinyl reissues of our old faves possess the sound of yesterday, but they can’t tell us a thing about how it all looked.

And that’s where you, the guy with the camera, come in.

ROUNDING TO THE NEXT BEST YOU

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU MAY FIND, AS I HAVE, THAT MANY OF THE BEST PHOTOGRAPHERS ARE ALSO, ARTISTICALLY, SPEAKING, “SOMETHING ELSE“. That is, their creative energies emerge in more than just one medium, even if images are their preferred language. This has always been thus. During the camera’s infancy, many photogs were former painters. Writers were also among the first to explore the new art of picture-making, and the amateur photo work of scribes like Emile Zola and Lewis Carroll remain worthy of note today.

In the 20th century, some painters-turned-photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson turned back to the brush late in life, while other artists like Man Ray stayed firmly anchored in both camps. And even the great theologian and poet Thomas Merton spent his last years as a Trappist monk dabbling in a kind of zen expressionism through the viewfinder of his Canon 35mm.

This doesn’t exactly prove that everyone who is adept in one kind of art will also be effective as a photographer, but it does demonstrate that some people who are curious in all ways of expression will sometimes also choose the camera as an instrument. I personally believe that this can only improve your way of seeing, since “vision” isn’t achieved merely through the eyes, but through the accumulation of all one’s life experience.

I would even go one step farther and claim that just studying photography may be bad for one’s development as a photographer. Rather, it is the total weight of one’s life which shapes one’s seeing, just as a worldlier view can inform one’s writing, cooking, singing, or strumming. No one art is so complete that it can operate in a vacuum, sealed away from all the other arts.

We readily accept that composers need to occasionally be historians, that writers should sometimes be philosophers, and that both painters and chefs should master a little science, so how can we believe that photographers can comment on the whole of life without at least dabbling in the world beyond their computers or darkrooms? You cannot be willfully blind as a person and visionary as a photographer at the same time. The more there is of you, the more of you there is that makes it into your pictures.

MODEL CITIZENS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE ROLE OF THE URBAN PHOTOGRAPHER IS TO REKINDLE OUR RELATIONSHIP to our cities, to ignite a romance that might have gone cold or fizzled out. We grow up inside the buildings and streets of our respective towns one day at a time, and, while familiarity doesn’t always breed contempt, the slow, steady drip of repetitive sequence can engender a kind of numb blindness, in that we see less and less of the places we inhabit. Their streets and sights become merely up, down, in, out, north side or east side, and their beauty and detail dissolve away before the regular hum of our lives.

An outside eye, usually trained on a camera, is a jolt of recognition, as if our city changed from a comfy bathrobe into a cocktail dress. We even greet images of our cities with cries of “where’s THAT????”, as if we never saw these things before. The selective view of our streets through a camera, controlling framing, context, color and focus, enchants us anew. If the photog does his job properly, the magic is real: we truly are in new territory, right in our own backyards.

A city with iconic landmarks, those visual logos that act as absolute identifiers of location, actually are easier for the urban photographer, since their super-fame means that many other remarkable places have gone under-documented. Neighborhoods are always rising and falling, as the Little Italys fade and the Chinatowns ascend. Yesterday’s neglected ghetto becomes today’s hip gallery destination. Photographers can truly rock us out of the lethargy of daily routine and reveal the metropolis’s forgotten children in not only aesthetic but journalistic ways, reminding us of problems that need remedy, lives that plead for rescue.

The photographer in the city is an interpretive artist. His mantra: hey, townies, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

GAS ATTACK

The first-ever cause of Gotta-Getta-Toy disease in my life, the Polaroid Model 95 from 1949. Ain’t it purty?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AT LEAST TWO ACQUAINTANCES HAVE RECENTLY APPROACHED ME, knowing that I shoot with Nikons, to gauge my interest in buying their old lenses. One guy has, over the years, expertly used every arrow in his technical quiver, taking great pictures with a wide variety of glass. He’s now moving on to conquer other worlds. The other, I fear, suffered a protracted attack of G.A.S., or Gear Acquisition Syndrome, the seductive illness which leads you to believe that your next great image will only come after you buy This Awesome Lens. Or This One. Or…

Perk’s Law: the purchase of photographic equipment should be made only as your ability gradually improves to the point where it seems to demand better tools to serve that advanced development. Sadly, what happens with many newbies (and Lord, I get the itch daily, myself) is that the accumulation of enough toys to cover any eventuality is thought to be the pre-cursor of excellence. That’s great if you’re a stockholder in a camera company but it fills many a man’s (and woman’s) closet with fearsome firepower that may or may not ever be (a) used at all or (b) mastered. GAS can actually destroy a person’s interest in photography.

Here’s the pathology. Newbie Norm bypasses an automated point-and-shoot for his very first camera, and instead, begins with a 25-megapixel, full-frame monster, five lenses, two flashes, a wireless commander, four umbrellas and enough straps to hold down Gulliver. He dives into guides, tutorials, blogs, DVDs, and seminars as if cramming for the state medical boards. He narrowly avoids being banished from North America by his wife. He starts shooting like mad, ignoring the fact that most of his early work will be horrible, yet valuable feedback on the road to real expertise. He is daunted by his less-than-stellar results. However, instead of going back to the beginning and building up from simple gear and basic projects, he soon gets “over” photography. Goodbye, son of Ansel. Hello Ebay.

This is the same guy who goes to Sears for a hammer and comes back with a $2,000 set of Craftsman tools, then, when the need to drive a nail arrives, he borrows a two dollar hammer from his neighbor. GAS distorts people’s vision, making them think that it’s the brushes, not the vision, that made Picasso great. But photography is about curiosity, which can be satisfied and fed with small, logical steps, a slow and steady curve toward better and better ways of seeing. And the best thing is, once you learn that,you can pick up the worst camera in the world and make music with it.

There is no shortcut.There are no easy answers. There is only the work. You can’t lose thirty pounds of ugly fat in ten days while eating pizza and sleeping in late. You need to stay after class and go for the extra credit.

THE GENESIS OF REAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

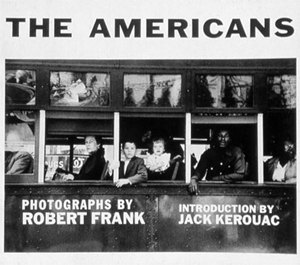

“(the book is) flawed by meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposure, drunken horizons, and general sloppiness, (showing) a contempt for quality and technique…” –Popular Photography, in its 1958 review of The Americans

THOSE WORDS OF DISDAIN, designed to consign its subject to the ash heap of history, are now forever attached to the photographic work that, instead of vanishing in disgrace, almost single-handedly re-invented the way the world saw itself through the eye of a camera. For to thumb through Robert Frank’s 1958 collection of road images, The Americans, is to have one’s sense of what is visually important transformed. Forever.

THOSE WORDS OF DISDAIN, designed to consign its subject to the ash heap of history, are now forever attached to the photographic work that, instead of vanishing in disgrace, almost single-handedly re-invented the way the world saw itself through the eye of a camera. For to thumb through Robert Frank’s 1958 collection of road images, The Americans, is to have one’s sense of what is visually important transformed. Forever.

In the mid-1950’s, mass-market photojournalist magazines from Life to Look regularly ran “essays” of images that were arranged and edited to illustrate story text, resulting in features that told readers what to see, which sequence to see it in, and what conclusions to draw from the experience. Editors assiduously guided contract photographers in what shots were required for such assignments, and they had final say on how those pictures were to be presented. Robert Frank, born in 1924 in Switzerland, had, by mid-century, already toiled in these formal gardens at mags that included Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, and was ready for something else, a something else where instinct took preference over niceties of technique that dominated even fine-art photography.

Making off for months alone in a 1950 Ford and armed only with a 35mm Leica and a modest Guggenheim grant, Frank drove across much of the United States shooting whenever and wherever the spirit moved him. He worked quickly, intrusively, and without regard for the ettiquette of formal photography, showing people, places, and entire sub-cultures that much of the country had either marginalized or forgotten. He wasn’t polite about it. He didn’t ask people to say cheese. He shot through the windshield, directly into streetlights. He didn’t worry about level horizons, under-or-over exposure, the limits of light, or even focal sharpness, so much as he obsessed about capturing crucial moments, unguarded seconds in which beauty, ugliness, importance and banality all collided in a single second. Not even the saintly photojournalists of the New Deal, with their grim portraits of Dust Bowl refugees, had ever captured anything this immediate, this raw.

Frank escaped a baker’s dozen of angry confrontations with his reluctant subjects, even spending a few hours in local jails as he clicked his way across the country. The terms of engagement were not friendly. If America at large didn’t want to see his stories, his targets were equally reluctant to be bugs under Frank’s microscope. When it was all finished, the book found a home with the outlaw publishers at Grove Press, the scrappy upstart that had first published many of the emerging poets of the Beat movement. The traditional photographic world reacted either with a dismissive yawn or a snarling sneer. This wasn’t photography: this was some kind of amateurish assault on form and decency. Sales-wise, The Americans sank like a stone.

Around the edges of the photo colony, however, were fierce apostles of what Frank had seen, along with a slowly growing recognition that he had made a new kind of art emerge from the wreckage of a rapidly vanishing formalism. One of the earliest converts was the King of the Beats Himself, no less than Jack Kerouac, who, in the book’s introduction said Frank had “sucked a sad poem right out of America and onto film.”

Today, when asked about influences, I unhesitatingly recommend The Americans as an essential experience for anyone trying to train himself to see, or report upon, the human condition. Because photography isn’t merely about order, or narration, or even truth. It’s about constantly changing, and re-charging, the conversation. Robert Frank set the modern tone for that conversation, even if he first had to render us all speechless.

FOR A LIMITED TIME ONLY

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

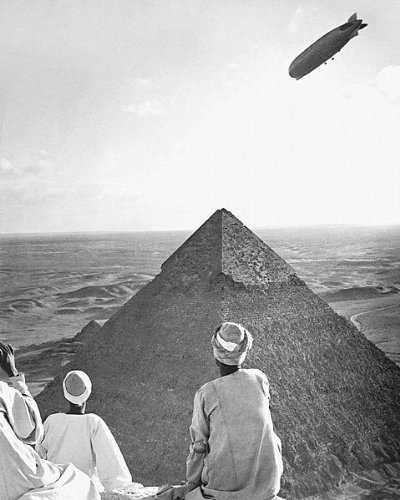

ONCE WE WERE ABLE TO CAPTURE LIGHT IN A BOX, in the earliest days of photography, there seemed to be a worldwide obsession with recording things before they could vanish. Painters might linger in a wistful sunset over a craggy shoreline, and certainly that was part of the photographer’s prerogative as well, but, immediately following the introduction of the first semi-portable cameras, there was a concurrent surge in the recording of the ancient world…temples, churches, monuments, pyramids, waterfalls, Africa, Asia, empires new and old.

The nineteenth century saw an explosion in the number of world tours available to at least the wealthy, as seen in The Innocents Abroad, Mark Twain’s chronicling of a global excursion of Americans to the venerable ports of the old world. Cartes-de-visites (later post cards), stereoscopic views and leather-bound books of armchair photo anthologies sold in the millions, and the first great urban photographers like Eugene Atget began to “preserve” the vanishing elements of their world, from Paris to Athens, for posterity and, quite often, for profit.

This first-generation fever among shooters carried forth through two World Wars, the Great Depression, and into the journalistic coverage of revolutions and disasters seen in the present day. The photographer is aware that this is all going away, and that bearing witness to its disappearance is important. We can’t help but realize that the commonplace is on its way to becoming the rare, and eventually the extinct. We can’t know what things we regard as banal will eventually assume the importance of the contents of the pharaoh’s tombs. Ramses’ everyday toilet items become our priceless treasures. Now, however, instead of sealing up pieces of the world in pyramids, we imprison the light patterns of it, with history alone to judge its value.

Making pictures is taking measure of our world. It is our voice preserved for another time. This is what we looked like. This is what we thought was important. This shows the distance of our journey. New worlds are always crowding out old ones. Photography slows that process so we can see where one curtain comes down and another rises.

YESTERGRUBBING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I ALWAYS SCRATCH MY HEAD WHEN I SEE AN EATERY sporting a sign that boasts “American Cuisine”, and often have to suppress an urge to step inside such joints to ask the proprietor to explain just what that is. If there is one thing about this sprawling broad nation that can’t be conveniently corralled and branded, it’s the act of eating. Riff through a short stack of Instagrams to see the immense variety of foodstuffs that make people say yum. And as for the places where we decide to stoke up….what they look like, how they serve us, how they feel….well, that’s a never-ending task, and joy, for the everyday photographer.

Eating is, of course, more than mere nourishment for the gut; it’s also a repast for the spirit, and, as such, it’s an ongoing human drama, constantly being shuffled and re-shuffled as we mix, mingle, disperse, adjourn and regroup in everything from white linen temples of taste to gutbucket cafes occupying speck of turf on endless highways. It’s odd that there’s been such an explosion of late in the photographing of food per se, when it’s the places where it’s plated up that hold the real stories. It’s all American, and it’s always a new story.

I particularly love to chronicle the diners and dives that are on the verge of winking out of existence, since they possess a very personalized history, especially when compared with the super-chains and cookie-cutter quick stops. I look for restaurants with “specialities of the house”, with furniture that’s so old that nobody on staff can remember when it wasn’t there. Click. I yearn for signage that calls from the dark vault of collective memory. Bring on the Dad’s Root Beer. Click. I relish places where the dominant light comes through grimy windows that give directly out onto the street. Click. I want to see what you can find to eat at the “last chance for food, next 25 mi.” Click. I listen for stories from ladies who still scratch your order down with a stubby pencil and a makeshift pad. Click. Click. Click.

In America, it’s never just “something to eat”. It’s “something to eat” along with all the non-food side dishes mixed in. And, sure, you might find a whiff of such visual adventure in Denny’s #4,658. Hey, it can happen. But some places serve up a smorgasbord of sensory information piping hot and ready to jump into your camera, and that’s the kind of gourmet trip I seek.

ARCHITECTS OF HOPE

Part of Jose Maria Sert’s soaring mural American Progress (1937) above the main information desk just inside the entrance to 30 Rockefeller Plaza.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE EROSION AND COLLAPSE OF THE GREAT AMERICAN URBAN INFRASTRUCTURES of the 20th century is more than bad policy. It is more than reckless. It is also, to my mind, a sin against hope.

As photographers, we are witness to this horrific betrayal of the best of the human spirit. The pictures that result from this neglect may, indeed, be amazing. But we capture them with a mixture of sadness and rage.

Hope was a rarity in the early days of the Great Depression. Prosperity was not quite, as the experts claimed, “right around the corner.” And yet, a strategy arose, in private and federal project alike, that offered uplift and utility at the same time. People were put to work making things that other people needed. The nation erected parks, monuments, utilities, forests, and travel systems that turned misery to muscle and muscle to miracle. Millionaires used their personal fortunes to create temples of commerce and towers of achievement, hiring more men to turn more shovels. Hope became good business.

One of the gleaming jewels of the era was, and is, the still-amazing Rockefeller Plaza in New York, which, in its decorative murals and reliefs, lionized the working man even as it put bread on his table. The dignity of labor was reflected across the country in everything from newspaper lobbies to post office portals, giving photographers the chance to chronicle both decline and recovery in a country brought only briefly to its knees.

Today, the information desk at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, home of NBC studios, still provides a soaring tribute to the iron workers and sandhogs who made it possible for America to again put one foot in front of the other, marching, not crawling, back into the sunlight. It still makes a pretty picture, as can thousands of such surviving works across the country. Photographing them in the current context of priceless inheritance offers a new way to thank the bygone architects of hope.

WITH THESE HANDS

The Gundlach-Korona View Camera (1879-1930), about as opposite from “portable” or “convenient” as you get.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

EVERY ONCE IN A WHILE, AS A PHOTOGRAPHER, I NEED TO RENEW MY SENSES OF GRATITUDE AND HUMILITY, and I refresh both by leafing through a hefty tome called View Camera Technique, a 300-plus page collection of graphs, diagrams and tables on what still stands as the most technically immersive photographic instrument of all time. I use the word immersive because all of the view’s operations must be mastered through personal, direct calculation of a horde of formulae. Nothing is automatic. Results can only be wrung out of the device by the most exacting calculations. The guaranteed given of the view camera: there will be math on the final.

The aforementioned gratitude and humility come from the fact that I am free of the Pythagorean calculus that it took for earlier shooters to master their medium, and the knowledge that I will never apprehend even half of the raw science needed to summon images forth from these simply built, but technically unforgiving cameras. However, along with a hugh whew of relief comes just a slight pang of regret, since the camera has gone the way of many other tools that used to be in a direct, cause-and-effect relationship with the human hand.

As a kind of strangely timed stream-of-consciousness, my most recent review of View Camera Technique was followed, just a day later, by a visit to a local art foundry, a unique marriage of state-of-the-art kilns and caveman-simple hand tools, many of which were arranged on work benches near the visitors’ center, looking very much as if the past 500 years had not occurred. The marvel of hand tools is that, visually, they put us right back into an age when the world only yielded a working life to the direct, simple transmission of human force and will to a physical object. The use of a hammer is an unambiguous and impeccably clear transaction. You either drove the nail or you don’t. As Yoda said, there is no try.

Cameras no longer require us to wrestle directly with them to extract a photograph by real exertion, and that should give us, as shooters, an appreciation for those remaining implements which still do convey simple, A-B energy from hand to tool. Such objects remain powerful symbols for action, for creation, and for our urge to personally shape our world. And there must still be a great many pictures that we can summon forth to celebrate that relationship.

7/4/15: OH, SAY, CAN YOU SEE?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR AS LONG AS THERE HAS BEEN PHOTOGRAPHY, the United States of America has flown some version of the Stars and Stripes, a banner that has symbolized, in cloth and thread, what we profess and hope for ourselves as one of the world’s experiments in self-government. That argues for the flag being one of the most photographed objects in history, and, therefore, one of the most artistically problematic. Those things that are visualized most, by most of us, endure the widest extremes in interpretation, as all symbols must, and observing that phenomenon as it applies to the flag is both fascinating and frustrating.

Fascinating, because the flag can embody or evoke any emotion, any association, any memory, providing a gold mine for photographers who always must look beyond the mere recording of things to their underlying essences. Frustrating, because that task can never be complete, in that there can be no definitive or final statement about a thing that resonates so intensely, so personally with a diverse nation. Photographing the flag is always new, or, more precisely, it can always be made new.

The problem with fresh photographic approaches to the flag is really within ourselves. The banner is so constantly present, on public buildings, in pop culture, even as commentary, that it can become subliminal, nearly invisible to our eye. Case in point: the image at left of the front facade to Saks’ in Manhattan. The building is festooned in flags across its entire Fifth Avenue side, which is, being across the street from Rockefeller, a fairly well-trafficked local. And yet, in showing this photo to several people from the city, I have heard variations on “where did you take that?” or “I never noticed that before” even though the display is now several years old.

And that’s the point. Saks’ flags have now become as essential a part of the building as its brick and mortar, so that, at this point, the only way the building would look “wrong” or “different” is if the flags were suddenly removed. Training one’s eye to see afresh what’s just been a given in their world is the hardest kind of visual re-training, and the American flag, visually inexhaustible as a source of artistic interpretation, can only be blunted by how much we’ve forgotten to see it.

Photography has found a cure for sharpness, clarity, exposure, even time itself. But it can’t compensate for blindness. That one’s on us.

THE LOOK OF SILENCE

Slurry Wall And Hero’s Girder, 2015. The 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York is a cathedral of grim silence.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS THE MOST PHOTO-DOCUMENTED EVENT IN HUMAN HISTORY, the attacks of September 11, 2001 have spawned images that can never be unseen. Images that tear at you, slam you in the back of the head, wring tears and rage from you, stun you mute.

As the keeper and curator of many of the most powerful of these images, the 9/11 Memorial Museum in lower Manhattan has achieved a tough but fair balance of emotion and academia. Given the staggering number of people whose personal stake in this space covers every human motive and perspective, the making of this part-exhibit-part-shrine may have been one of the most thankless jobs imaginable.

And yet the job has been done, with eloquence and a spare, stark restraint that is poetic. Visiting the museum is no easy task. As Shakespeare said, if you have tears to shed, prepare to shed them now. But visit you should, and, yes, there is something that a camera can capture there without being crass or irreverent. The designers have seen to it.

Firstly, they have guaranteed that the main central exhibits of debris, personal documents, voice messages and news video are completely off-limits to any kind of photography. Walk in there, and you’ll know why. Those who accidentally caught this epic horror in the moment of its occurrence will never be equaled or surpassed by anyone taking a casual snap on a smartphone anyway, and trying to do so would be like setting off sparklers at a requiem mass.

Firstly, they have guaranteed that the main central exhibits of debris, personal documents, voice messages and news video are completely off-limits to any kind of photography. Walk in there, and you’ll know why. Those who accidentally caught this epic horror in the moment of its occurrence will never be equaled or surpassed by anyone taking a casual snap on a smartphone anyway, and trying to do so would be like setting off sparklers at a requiem mass.

No, the real photographic opportunities are in the dark, cavernous spaces under the surface of the street, dim caves that make you feel as if you yourself, are, for a moment, trapped, running out of light and time. The enormous foundation known as the slurry wall, which, in surviving the titanic forces of the towers’ collapse, kept the Hudson River from flooding all of lower Manhattan. The rusted girder that, like a day-glo-autographed tombstone, bears the signature of every working company of first responders that slaved away at Ground Zero, first as rescuers, next as salvagers, always as heroes.

It is here, in the quiet arrangement of these incredibly scaled spaces, that the 9/11 Memorial Museum becomes more spiritual than any hour you will ever pass in church. It is in these dark, harrowing parts of the hall that you fully sense what a slender thread we all hang from, and understand that light and darkness struggle for the same real estate, now as then.

“GEE”-EYE JOE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S NOT UNFAIR TO ARGUE THAT MOST MAJOR PHOTOGRAPHERS ARE FAR MORE ELOQUENT with their lenses than with their tongues. The fact that their eyes speak volumes is what distinguishes them as artists, not whatever quick quips they may toss off about why they do what they do. There are a few shooters per generation, however, who really add to the art by sharing the motivations that accompany the making of it. Joe McNally is one such photographer.

Joe, whose work ranges from National Geographic, Life, and Sports Illustrated to his groundbreaking Faces Of Ground Zero, speaks not as a pristine philosopher, but as the grizzled, hard-boiled, run-and-gun, reality-anchored pro that he is. He knows deadlines. He knows the cigar-chomping breath of hate-crazed editors. He know what moves, both emotionally and commercially. And he has written two of the era’s best books (The Moment It Clicks and Hotshoe Diaries) on the real struggles that arise for the professional in the field. No esoteric essays. Just straight-from-the-shoulder truths from the world. A few Joe-isms to treasure forever:

No matter how much crap you gotta plow through to stay alive as a photographer, no matter how many bad assignments, bad days, bad clients, snotty subjects, obnoxious handlers, wigged-out art directors, technical disasters, failures of the mind, body, and will, all the shouldas, couldas, and wouldas that befuddle our brains and creep into our dreams, always remember to make room to shoot what you love. It’s the only way to keep your heart beating as a photographer.

or: I can’t tell you how many pictures I’ve missed, ignored, trampled, or otherwise lost just ‘cause I’ve been so hell bent on getting the shot I think I want.

This is the voice of a guy who’s been stomped on, crowded out, smashed up and beaten silly in the cause of a picture. This is a go-to guy when you want to learn about how to make tough calls and hard choices. And it’s the indefatigable spirit of photography telling you that, however you go out, don’t come back in without the picture. That means to always be looking, and to always be ready, and willing to:

Put it to your eye. You never know. There are lots of reasons, some of them even good, to just leave it on your shoulder or in your bag. Wrong lens. Wrong light. Aaahhh, it’s not that great, what am I gonna do with it anyway? I’ll have to put my coffee down. I’ll just delete it later, why bother? Lots of reasons not to take the dive into the eyepiece and once again try to sort out the world into an effective rectangle. It’s almost always worth it to take a look.

And how does he shoot? Twice as good as he talks. Photographers need, always, to reject comfort, familiarity, habit, ease. Joe’s “Gee” eye reminds us to stay hungry.

And stay on the job.

HEADSTONES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IF ARCHITECTURAL PROJECTS, AT THEIR BIRTHS, REPRESENT A KIND OF FAITH, then the demise of buildings likewise signals a sort of death, a loss of belief, an admission of failure. Our new societies break ground on developments in one generation only to see them wither to silence in the next, a cycle of boom and bust that somehow has become the rhythm of modern life.

Viewing the ruins that result from all our once-bright industrial dreams through the lens of a camera creates a peculiar kind of commentary, less specific but more emotionally immediate than a written editorial or essay. The first uses of photography as chronicles of urban life were largely neutral, merely recording city vistas, monuments, cathedrals, scenic wonders. It took the aftermath of World War One and the Great Depression to infuse architectural photos with the sting of commentary, as if the photographer was asking, what have we done? What is all this for?

In the 1930’s, there was a quick segue from the New Deal’s programs for documenting relief programs to a new breed of socially activist shooters like Walker Evans and Margaret Bourke-White, who showed us both the human and architectural faces of despair. Suddenly closed businesses, shabby tenements, and collapsed infrastructures became testimony on what we were doing wrong, of the horrific gap between our dreams and our deeds.

In every town across America, photographers continue to search for the headstones of our lost hopes, the factories, foundries, and dashed ventures that define who we hoped to be, and how things went wrong. It’s not a photography of hopelessness, however, but a dutiful reminder that actions have consequences, for good or ill. Turning our eyes, and lenses, to the stories left behind by the earlier versions of ourselves is a way of measuring, of keeping score on what kind of world we desire. The headstones bear clear inscriptions. Deciphering them is the soul of photography.

DIGGING OUT OF THE DRYS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS, IN THE NATURAL COURSE OF THEIR CONTINUING DEVELOPMENT, will, at one point or another, get hopelessly lost. Stuck. Stranded on a desert island. Fumbling for the way out of the scary forest. Artistically adrift. Call it a dead spot, a dry spell, or shooter’s cramp, but you can expect to hit a stretch of it at some time. The pictures won’t come. You can’t buy an idea. And, worst of all, you worry that it will last……like forever.

At such times it’s a great idea to turn yourself into a rabid researcher. The answer to how to get unstuck is, really, out there. In your pictures or in someone else’s. Let’s look at both resources.

Your own past photographs are a file folder of both successes and failures. Pore over both. There are specific reasons that some pictures worked, and other’s didn’t. Approach them with a fresh eye, as if a complete stranger had asked you to assess his portfolio. And be both generous and ruthless. You’re looking for truth here, not a security blanket.

Beyond your own stuff, start drilling down to the divinity of your heroes, those legends whose pictures amaze you, and who just might able to kick your butt a little. And, just so we’re being fair, don’t confine yourself to studying just the gold standard guys. Make yourself look at a whole bunch of bad upstarts and find something, even a small thing, that they are doing right that you’re not. Discover a newbie who shoots like an angel, or an Ansel. Empathize with someone who needs even more help than you do. Once you have mercy on someone else’s lack of perfection, it’s a lot easier to forgive it in yourself.

We “artistes” love to believe that all greatness happens in isolation, just our art and us and the great god Inspiration. But even when you shoot alone, you’re in a kind of phantom collaboration with everyone else who ever took a picture. And that’s as it should be. Slumps happen. But the magic will come back. You just need to know how to reboot your mojo.

And smile. It’s photography, after all.

WHAT’S THIS I SEE?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS PHOTOGRAPHERS, WE HAVE A LIFETIME OF HEART-TO-HEART TALKS with ourselves, seeking the answer to questions like “what’s this I see?”, or “what do I want to tell?” Tricky thing is, of course, that, as time progresses, you are talking with a variety of conversational partners. As we age, we re-engineer nearly every choice-making process or system of priority. I loved Chef-By-Ar-Dee as an eight-year-old, but the sight of the old boy would probably make me gag at 63. And so it goes with clothing, choice of good reads, and, of course photography.

One of the things it’s prudent to do over the years is to take the temperature of present-day You, to really differentiate what that person wants in an image, versus what seemed essential at other stages in your life. I know that, in my case, my favorite photographers of fifty years ago bear very little resemblance to the ones I see as signposts today.

As a boy, I was in love with technical perfection and a very literal form of storytelling. Coming up in an artist’s household, I saw photos as illustrations, that is, subservient to some kind of text. I chose books for their pictures, yes, but for how well they visualized the writing in those books. The house was chock full of the mass-appeal photo newsmagazines of that day, from Life to Look to National Geographic to the Saturday Evening Post, periodicals that chose pictures for how well they completed the stories they decorated. A picture-maker for me, then, basically a writer’s assistant.

By my later school years, I began, slowly, to see photographs as statements unto themselves, something beyond language. They were no longer merely aids to understanding a writer’s position, but separate, complete entities, needing no intro, outro or context. The pictures didn’t have to be “about” anything, or if they were, it wasn’t a thing that was necessarily literal or narrative. Likewise, the kind of pictures I was interested in making seemed, increasingly, to be unanchored from reference points. Some people began to ask me, “why’d you make a picture of that?” or “why aren’t there any people in there?”

By this time in my life, I sometimes feel myself rebelling against having any kind of signature style at all, since I know that any such choice will eventually be shed like snake-skin in deference to some other thing I’ll deem important. For a while. What this all boils down to is that the journey has become more important than the destination, at least for my photography. What I learn is often more important than what I do about it.

And some days, I actually hope I never get where I’m going.

AND FEATURING LINDA ON LENS

Even if you don’t know her work, you know her work. Linda McCartney’s classic portrait of her husband and a friend made album art history in 1970.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONCE LINDA EASTMAN BECAME LINDA McCARTNEY, the world ignorantly chose to define her as rock’n’roll arm candy basking in the reflected sun of her globally famous husband. In fact, however, by the time she chose to rock a family, she had already created a self that would outlast her role as a reluctant musician and perennial target of every wise-ass disk jockey from London to New York. She did it with a remarkable, natural eye for composition and the untrained instinct to know where to click, and when. While her bandmates wielded electric axes to give voice to their muses, Linda wailed with a Hasselblad.

By the time she became a Mrs. Beatle, Linda had already become the first great photographer in rock history, pioneering an intimate, direct style that humanized its bright lights and consigned the formal portraits of the record label’s in-house shooters to the dustbin. It is work that, finally, in recent years, has been allowed to glow as the star trove that it is, eclipsing her much-derided designations as Yoko With A Tambourine, A Pig With Wings, or whatever other lame tag the hacks in the rock press felt like hanging on her. Recent showings of her work in America, Europe, even South Korea continue to celebrate her instinctual knack for showing the human inside the star. And none of it was by the book.

She didn’t ignore the rules; she simply didn’t know they existed. She never had a formal studio, shopping for backgrounds and locales on the fly. She never used flash, ever, believing that it was bulky and off-putting. She attended exactly one class on photography, was told she had talent, and never went back for lesson two. She gave away original negatives of her top shots to friends, finding herself with nothing to sell to publishers except the “shoves”, lesser takes which, somehow, were still better than what everyone else was doing with this crazy longhair music.

What kind of photographer was this? Linda never posed people, forgot to re-calculate the ASA (ISO) settings when switching from color to black and white, sent the magazines blurred concert shots. And despite her never joining the ranks of the camera-ly cultured, the true souls of the Rolling Stones, The Doors, The Yardbirds, Jimi, Janis, Dylan, and, most notably, the Beatles shone forth in her grainy frames. Linda Eastman McCartney captured the dawning genius in them all, before the crank-up of the hype machines, before the twilight of the vultures, before rock careened from the summer of love to the winter of our discontent.

After Paul, the images were family candids, and yet the vision shone forth, most famously in her shot of baby Mary peeking out of her Beatle daddy’s jacket on a morning stroll, the rear-cover photo for the McCartney album in 1970. From that point on, the farm and the fam were everything, the road and the tour bus, not so much. She chose to settle for being Mrs. Paul, the girl who couldn’t sing but who hitched a ride on one of the biggest pop rockets of the ’70s. Decades later, what her eye saw way back then seems inevitable, her work the official chronicle of so many moments that mattered. Linda left us in 1998, but she left us that eye. It is a smiling eye, an innocent one, and one which was magnificently focused on the stuff of dreams.

NEW WINE FROM OLD BOTTLES

Wide-angle on a budget, and in a time warp: a mid-70’s manual 24mm Nikkor prime up front of my Nikon D5100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MANY OF US WHO BEGAN THEIR LOVE FOR PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE DAYS OF FILM have never really made a total switch to digital. It just never was necessary to make that drastic a “clean break” with the past. Far from it: through the tools and techniques that we utilized in the analog world, we still carry forth viewpoints and habits that act as foundations for the work we produce in pixels. Photography was not “re-invented” by digital in the way that transportation was when we moved from horse to car. It was refined, adding a new chapter, not an entire book.

Digital is merely the latest in a historical line of ever-evolving recording media, from daguerreotypes to salted paper to glass plates to roll film. The principles of what makes a good picture, plus or minus some philosophical fashion from time to time, have not changed. That means that tons of toys from the analog world still have years of life left in them, especially lenses.

Call it a “reverse hack” mentality, call it sentiment, but some shooters are reluctant to send all their various hunks of aged camera glass to the ashcan simply because they were originally paired with analog bodies. Photography is expensive enough without having to start from scratch with all-new components every time a hot new product hits the market, and many of us look for workarounds that involve giving a second life to old lenses. New wine from old bottles.

Some product lines actually engineer backwards-compatibility into their lenses. Nikon was the first and best company to spearhead this particular brain flash, making lenses for over forty years that can be pressed into service with the latest Nikon body off the production line. In my own case, I have finally landed a Nikon 24mm f/2.8 prime, not from current catalogues, but from the happy land of Refurbia. It’s a 1970’s-era gem that is sharp, simple, and mine-all-mine, for a fifth of the cost of the latest version of the same optic.

My new/old 24 gives me a wide-angle that’s a full stop more light-thirsty than the most current kit lenses in that focal length, and is also small, light, and quick, even as a manual focus lens. And it can be argued that the build quality is better as well. Photography is about results, not hardware, so how you get to the finish line is your business. And yet, sometimes, I must admit that shooting new pictures with legendary lenses feels like photography, as an art, is building on, and not erasing, history.

25, 50, T, B

By MICHAEL PERKINS

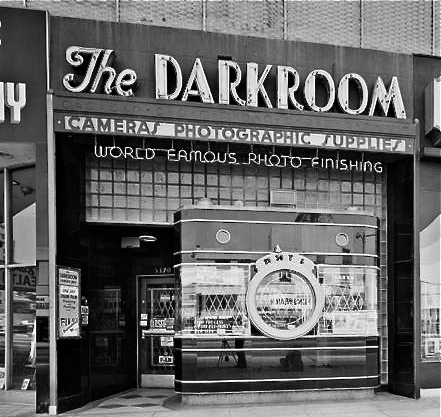

THERE IS A PART OF WILSHIRE BOULEVARD IN LOS ANGELES that I have been using for a photographic hunting ground for over ten years, mostly on foot, and always in search of the numerous Art Deco remnants that remain in the details of doors, window framings, neighborhood theatres and public art. Over the years, I have made what I consider to be a pretty thorough search of the stretch between Fairfax and LaBrea for the pieces of that streamlined era between the world wars, and so it was pretty stunning to realize that I had been repeatedly walking within mere feet of one of the grand icons of that time, busily looking to photograph….well, almost anything else.

A few days ago, I was sizing up a couple framed in the open window of a street cafe when my composition caught just a glimpse of black glass, ribbed by horizontal chrome bands. It took me several ??!?!-type minutes to realize that what I had accidentally included in the frame was the left edge of the most celebrated camera in all of Los Angeles.

Opened in the 1930’s, the Darkroom camera shop stood for decades at 5370 Wilshire as one of the greatest examples of “programmatic architecture”, that cartoony movement that created businesses that incorporated their main product into the very structure of their shops, from the Brown Derby restaurant to the Donut Hole to, well, a camera store with a nine-foot tall recreation of an Argus camera as its front facade.

The surface of the camera is made of the bygone process known as Vitrolite, a shiny, black, opaque mix of vitreous marble and glass, which reflects the myriad colors of Los Angeles street life just as vividly today as it did during the New Deal. The shop’s central window is still the lens of the camera, marked for the shutter speeds of 1/25th and 1/50th of a second, as well as T (time exposure) and B (bulb). A “picture frame” viewfinder and two film transit knobs adorn the top of the camera, which is lodged in a wall of glass block. Over the years, the store’s original sign was removed, and now resides at the Museum of Neon Art in Glendale, California, while the innards of the shop became a series of restaurants with exotic names like Sher-e-Punjab Cuisine and La Boca del Conga Room. Life goes on.

True to the ethos of L.A. fakes, fakes of fakes, and recreations of fake fakes, the faux camera of The Darkroom has been reproduced in Disney theme parks in Paris and Orlando, serving as…what else?….a camera shop for visiting tourists, while the remnants of the original storefront enjoy protection as a Los Angeles historic cultural monument. And, while my finding this little treasure was not quite the discovery of the Holy Grail, it certainly was like finding the production assistant to the stunt double for the stand-in for the Holy Grail.

Hooray for Hollywood.

SUNSETTING

They’ll Be Ready Tuesday (2015)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IN RAY BRADBURY’S WONDERFUL ONE-ACT PLAY, TO THE CHICAGO ABYSS, an old man equipped with a near-photographic memory makes both friends and enemies because he remembers so much of a world vanished in the aftermath of global war. His talent lies not merely in being able to conjure the world of large things….cathedrals, cars, countries, but of the micro-minutia of a life, a realm filled with the colors of cigarette packages, what compressed air sounded like hissing out of a newly opened can of coffee, the names of candy bars. The play reminds us that it is the million little pieces, the uncountable props of daily living, that matter…..especially when they are no more.

Professions and services offer the photographer the chance to preserve entire miniature worlds for the viewer, worlds which are in the constant process of sunsetting, of transitioning from “is” to “was”. Shops where we used to get our watches repaired. Bookstores that are now furniture warehouses. Home where those people we knew, oh, you know their names, used to live. Was it on the corner? Or over there?

Clip Joint (2016)

Even when long-familiar things survive in some form, they are not quite as we knew them. Does anyone still get their shoes re-soled? Was there ever a time when “salons” were just “barber shops”? Was it, long ago, some kind of luxury to weigh yourself for a penny in the bus station? Photos of these daily rituals take on even greater import as time re-contexualizes our lives, shuffling our position in the cosmic deck. Decades hence, we almost need visible evidence that we ever lived this way, ever dressed like that.

I love shooting businesses that should not be around, but are, places that should have already been scrubbed from day-to-day experience, but stubbornly linger around the edges. Images taken of these places argue strongly that not all forward motion is progress, that the familiar and the comfortable are also little pieces of our identity. In the words of the old song, there used to be ballpark right here.

Here, I have a picture of it…..

Share this:

May 13, 2016 | Categories: Americana, Commentary, History, Nostalgia | Tags: documentary, Memories, popular culture, Street Photography | Leave a comment