SPLINTERING THE SQUARE

Times Square, August 2012. Somehow, the dark spaces in this spark my interest more than the garish light. 1/40 sec., F/8, ISO 320, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

GOING BACK OVER HUGE FOLDERS OF IMAGES LONG AFTER THE FACT OF THEIR CREATION, a kind of aesthetic amnesia comes over me as to what the original intent of some of the pictures were. Who is this person? And why can’t I remember being him when this thing was shot?

A bit of background:

As much time as I have spent in New York’s Time Square, I should know better than to even raise my camera to my face, given that this particular locale has produced, for me, more hot messes and failed missions than any other subject I’ve ever aimed at. The place is a mirage, a trap for shooters: a visual overload, obscenely loud and demanding of attention, but spectacularly devoid of content. There is no “message” afoot in this vast glowing urban canyon except step right up we got what you need right here great seats at half price a whole dinner for just ten bucks hey watch who yer shovin’.

Hey, if you’re looking for meaning, stay home and read your Bible.

And yet, every time I’m there, I still try to take “THE shot”, vainly sticking to the idea that there is even one in there, and that all I have to do is find it. If I only had a helicopter, if I shot it at this end of the street, if I just find the great unifying theme, the truth will come forth….

Yeah, right.

Anyway, in reviewing the above image, one I originally consigned to the dustbin, I’m once again that aesthetic amnesiac. I don’t recognize the person who took it. It doesn’t look like anything I’d try, since it’s just an arrangement of angles, colors, and dark spaces. In other words, an attempt to see a design in part of the scene, rather than an overall tapestry of the entire phenom. Sort of splintering the square. It’s the casting of the city as a personality, I guess, that appeals to me, like the Los Angeles of Blade Runner or the neon neo-Asia of Joel Schumacher’s Gotham City.

What adds to the mystery is the fact that, I’m not usually this loose. I’m a little too formalized in my approach, a mite too Catholic. I tend to have a plan, an intention. Let’s stick with the outline, kids, and proceed in order. Shooting from the hip and living in the moment is not instinctual to me. I’m always fighting with my inner anal bureaucrat.

I seriously don’t remember what I was going for here, and maybe, with a subject like this, that’s the only way to go. Stop calculating, stop plotting, just react, and treat Times Square as the amusement park ride it is. Going for “THE shot” has always given me dozens of , eh, sorta okay pix, but this approach appeals to me a little bit. I am not totally unpleased with it, or as a more eloquent writer might put it, it doesn’t suck.

And given my track record in Times Square, that’s slightly better than a break-even.

Now if I could only remember who took the damned thing…..

Related articles

LET THERE BE (MORE) LIGHT

A new piece of glass makes everything look better….even another piece of glass. First day with my new 35mm prime lens, wide open at f/1.8, 1/160 sec., ISO 100.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE RECENTLY BEEN EXPERIENCING ONE OF THOSE TIME MACHINE MOMENTS in which I am, again, right back at the beginning of my life as a photographer, aglow with enthusiasm, ripe with innocence, suffused by a feeling that anything can be done with my little black box. This is an intoxication that I call: new lens.

Without fail, every fresh hunk of glass I have ever purchased has produced the same giddy wonder, the same feeling of artistic invincibility. This time out, the toy in question is a Nikon f/1.8 35mm prime lens, and, boy howdy, does this baby perform. For cropped sensor cameras, it “sees” about like the 50mms of old, so its view is almost exactly as the human eye sees, without exaggerated perspective or angular distortion. Like the 50, it is simple, fast, and sharp. Unlike the 50, it doesn’t force me to do as much backing up to get a comfortable framing on people or near objects. The 35 feels a little “roomier”, as if there are a few extra inches of breathing space around my portrait subjects. Also, the focal field of view, even wide open, is fairly wide, so I can get most of your face tack sharp, instead of just an eye and a half. Matter of preference.

All this has made me marvel anew at how fast many of us are generally approaching the age of flashless photography. It’s been a long journey, but soon, outside the realm of formal studio work, where light needs to be deliberately boosted or manipulated, increasingly thirsty lenses and sensors will make available light our willing slave to a greater degree than ever before. For me, a person who believes that flash can create as many problems as it solves, and that it nearly always amounts to a compromise of what I see in my mind, that is good news indeed.

It also makes me think of the first technical efforts to illuminate the dark, such as the camera you see off to the left. The Ermanox, introduced by the German manufacturer Ernemann in 1924, was one of the first big steps in the quest to free humankind of the bulk, unreliability and outright danger of early flash. Its cigarette-pack-sized body was dwarfed by its enormous lens, which, with a focal length of f/2, was speedy enough (1/1000 max shutter) to allow sharp, fast photography in nearly any light. It lost a few points for still being based on the use of (small) glass plates instead of roll film, but it almost single-handedly turned the average man into a stealth shooter, in that you didn’t have to pop in hefting a lotta luggage, as if to scream “HEY, THE PHOTOGRAPHER IS HERE!!” In fact, in the ’20’s and ’30’s, the brilliant amateur shooter Erich Solomon made something of a specialty out of sneaking himself and his tiny Ermanox into high-level government summits and snapping the inner circle at its unguarded best (or worst). Long exposures and blinding flash powders were no longer part of the equation. Candid photography had crawled out of its high chair… and onto the street.

Today or yesterday, this is about more than just technical advancement. The unspoken classism of photography has always been: people with money get great cameras; people without money can make do. Sure, early breakthroughs like the Ermanox made it possible for anyone to take great low-light shots, but at $190.65 in 1920’s dollars, it wasn’t going to be used at most folks’ family picnics. Now, however, that is changing. The walls between “high end” and “entry level” are dissolving. More technical democracy is creeping into the marketplace everyday, and being able to harness available light affordably is a big part of leveling the playing field.

So, lots more of us can feel like a kid with a new toy, er, lens.

Related articles

- Prime Lenses (nikonusa.com)

- Understanding Focal Length (nikonusa.com)

I SEE YOUR FACE BEFORE ME

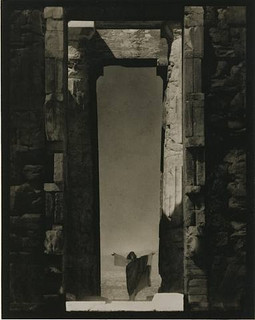

Edward Steichen’s amazing 1921 portrait of dance icon Isadora Duncan beneath a massive arch of the Parthenon in Greece, an image which recently surged to the top of my mind. See a link to a larger view of this shot, below.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE IMAGES SIT AT THE BOTTOM OF THE BRAIN, LIKE STONE PILLARS IN THE FOUNDATION OF AN IMMENSE TOWER.The structures erected on top of them, those images we ourselves have fashioned in memory of these foundations, dictate the height and breadth of our own creative edifices. Between these elemental pictures and what we build on top of them, we derive a visual style of our own.

In my own case,many of the pillars that hold up my own house of photography come from a single man.

Edward Steichen is arguably the greatest photographer in history. If that seems like hyperbole, I would humbly suggest that you take a reasonable period of time, say, oh, twenty years or so, just to lightly skim the breadth of his amazing career….from revealing portraits to iconic product shots to nature photography to street journalism and half a dozen other key areas that comprise our collective craft of light writing. His work spans the distance from wet glass plates to color film, from the Edwardian era to the 1960’s, from photography as an insecure imitation of painting to its arrival as a distinct and unique art form in its own right.

At the start of the 20th century, Steichen co-sponsored many of the world’s first formal photographic galleries, and was a major contributor to Camera Work, the first serious magazine dedicated wholly to photography. He ended his career as the creator of the legendary Family Of Man, created in the early 1950’s and still the most celebrated collection of global images ever mounted anywhere on earth. He is, simply, the Moses of photography, towering above many lesser giants whose best work amounts to only a fraction of his own prodigious output.

Which is why I sometimes see fragments of what he saw when I view a subject. I can’t see with his clarity, but through the milky lens of my own vision I sometime detect a flashing speck of what he knew on a much larger scale, decades before. The image at left recently rocketed to my mind’s eye several weeks ago, as I was framing shots inside a large government building in Ohio.In 1921, Steichen journeyed to Greece to use the world’s oldest civilization basically as a prop for portraits of Isadora Duncan, then in the forefront of American avant-garde dance. Framing her at the bottom of an immense arch in the ruins of the Parthenon, he made her appear majestic and minute at the same time, both minimized and deified by the huge proportions in the frame. It is one of the most beautiful compositions I have ever seen, and I urge you to click the Flickr link at the end of this post for a slightly larger view of it. (Also note the link to a great overview of Steichen’s life on Wikipedia.)

Uplighting creates a moody frame-within-frame feel at the Ohio Statehouse building, in a shot inspired by Edward Steichen’s images of massive arches. 1/30 sec., f/8, ISO 800, 18mm.

In framing a similarly tall arch leading into the rotunda of the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, I didn’t have a human figure to work with, but I wanted to show the building as a series of major and minor access cavities, in, around, under and through one of its arched entrance to the central lobby. I kept having to back up and step down to get at least a partial view of the rotunda and the arch at the opposite end of the open space included in the frame, which created a kind of left and right bracket for the shot, now flanked by a pair of staircases. Given the overcast sky meekly leaking grey light into the rotunda’s glass cupola, most of the building was shrouded in shadow, so a handheld shot with sufficient depth of field was going to call for jacked-up ISO, and the attendant grungy texture that remains in the darker parts of the shot. But at least I walked away with something.

What kind of something? There is no”object” to the image, no story being told, and sadly, no dancing muse to immortalize. Just an arrangement of color and shape that hit me in some kind of emotional way. That and Steichen, that foundational pillar, calling up to me from the basement:

“Just take the shot.”

Related articles

- The Photograph as a Social Statement (halsmith.wordpress.com)

- Picture Imperfect (andrewsullivan.thedailybeast.com)

- http://www.flickr.com/photos/quelitab/5793648357/lightbox/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Steichen

TURNING UP THE MAGIC

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CHRISTMAS IS SO BIG THAT IT CAN AFFORD TO GO SMALL. Photographers can, of course, tackle the huge themes….cavernous rooms bursting with gifts, sprawling trees crowning massive plazas, the lengthy curve and contour of snowy lanes and rustic rinks…..there are plenty of vistas of, well, plenty. However, to get to human scale on this most superhuman of experiences, you have to shrink the frame, tighten the focus to intimate details, go to the tiny core of emotion and memory. Those things are measured in inches, in the minute wonder of things that bear the names little, miniature, precious.

And, as in every other aspect of holiday photography, light, and its successful manipulation, seals the deal.

A proud regiment of nutcrackers, made a little more enchanting by turning off the room light and relying on tiny twinklers. 1/2 sec., f/4, ISO 100, 20mm

In recent years I have turned away from big rooms and large tableaux for the small stories that emanate from close examination of corners and crannies. The special ornament. The tiny keepsake. The magic that reveals itself only after we slow down, quiet down, and zoom in. In effect, you have to get close enough to read the “Rosebud” on the sled.

Through one life path and another, I have not been “home” (that is, my parents’ home) for Christmas for many years now. This year, I broke the pattern to visit early in December, where the airfare was affordable, the overall scene was less hectic and the look of the season was visually quiet, if no less personal. It became, for me, a way to ease back into the holidays as an experience that I’d laid aside for a long time.

A measured re-entry.

I wanted to eschew big rooms and super-sized layouts to concentrate on things within things, parts of the scene. That also went for the light, which needed to be simpler, smaller, just enough. Two things in my parents’ house drew me in: several select branches of the family tree, and one small part of my mother’s amazing collection of nutcrackers. In both cases, I had tried to shoot in both daylight and general night-time room light. In both cases, I needed some elusive tool for enhancement of detail, some way to highlight texture on a very muted scale.

Call it turning up the magic.

Use of low-power, local light instead of general room ambience enhances detail in tiny objects, revealing their textures. 1/2 sec., f/4, ISO 100, 20mm.

As it turned out, both subjects were flanked by white mini-lights, the tree lit exclusively by white, the nutcrackers assembled on a bed of green with the lights woven into the greenery. The short-throw range of these lights was going to be all I would need, or want. All that was required was to set up on a tripod so that exposures of anywhere from one to three seconds would coax color bounces and delicate shadows out of the darkness, as well as keeping ISO to an absolute minimum. In the case of the nutcrackers, the varnished finish of many of the figures, in this process, would shine like porcelain. For many of the tree ornaments, the looks of wood, foil, glitter, and fabric were magnified by the close-at-hand, mild light. Controlled exposures also kept the lights from “burning in” and washing out as well, so there was really no down side to using them exclusively.

Best thing? Whole project, from start to finish, took mere minutes, with dozens of shots and editing choices yielded before anyone else in the room could miss me.

And, since I’d been away for a while, that, along with starting a new tradition of seeing, was a good thing.

Ho.

Related articles

- How to Take a Picture of Your Christmas Tree (purdueavenue.com)

GRABBING THE GIFT

Light makes photography. Embrace light. Admire it. Love it. But above all, know light. Know it for all you are worth, and you will know the key to photography. ——-George Eastman

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN I WAS ASSEMBLING THE FIRST COMPILATION OF MY OWN IMAGES, Juxtapositions, I felt a little awkward about captioning the photos in any way, since they were clearly the work of an unaccomplished amateur. In my native Catholic thinking, my default question was, who the hell did I think I was to pontificate on anything, hmm? Notice that, since you are presently reading the musings of the selfsame unaccomplished amateur, I obviously got over past that obstacle, but anyway…

Needing the book to have some kind of general structure or theme, I decided that, although my own wisdom may not be in demand, there were plenty of thoughts from the greats in the photographic field that were worth re-quoting, and which, correctly placed, might even illustrate or amplify what I was trying to say in my own photos. It was a way of channeling great minds and acknowledging that, pro or amateur, we all started off on the same journey with much the same aims.

Looking at the finished book, I noticed that the two most consistent subjects among the finest minds in photography were (1) light; how to harness it, how to serve it, shape it, seek its ability to frame or exalt a subject and (2) the importance of staying flexible, open, and able to embrace the moment.

Both objectives came into clear focus for me last week. A combination of early sunlight, dense foliage and thick morning fog came together in breathtaking patterns in the high canyon rim streets of Santa Barbara, California. Light was busting out wherever it could, coming through branches and boughs in soft shafts that lent an almost supernatural quality to objects even a few feet away, which, when suffused with this satiny mist, were themselves softened, even abstracted. If there was ever a delicate, temporary gift of light, this was it, and I was suddenly in a hurry, lest it run away from me. Any picture I failed to take in the moment was lost within minutes. Overthinking meant going home empty.

There was no time to carefully read the tyrannical histogram, since I knew it would disapprove of the flood of white that would throw some of my shots off the graph. Likewise I couldn’t “cover” myself by bracketing exposures, since there was so much territory to cover, so many images to attempt before the light could mutate into something else. I needed to be shooting, not fiddling.

Better to burn out than to rust out, as Neil Young famously said. One particular arch of overhanging branches called me. It looked like this:

I was, after all these years, back to complete instinct. Snap shot? Certainly. Snap judgement? Hope not.

I didn’t go home empty. And when I got home, a re-check of one of Ansel Adams’ quotes encouraged me:

Sometimes, I do get to places where God’s ready for somebody to click the shutter.

Look for the moment. Listen for God (sometimes he whispers).

And don’t forget to click.

Related articles

- The 15 Most Popular Photography Tutorials from the 2nd Half of 2012 (digital-photography-school.com)

- What is photography? (bangladesh2u.com)

LOOK THROUGH ANY WINDOW, PART TWO

By MICHAEL PERKINS

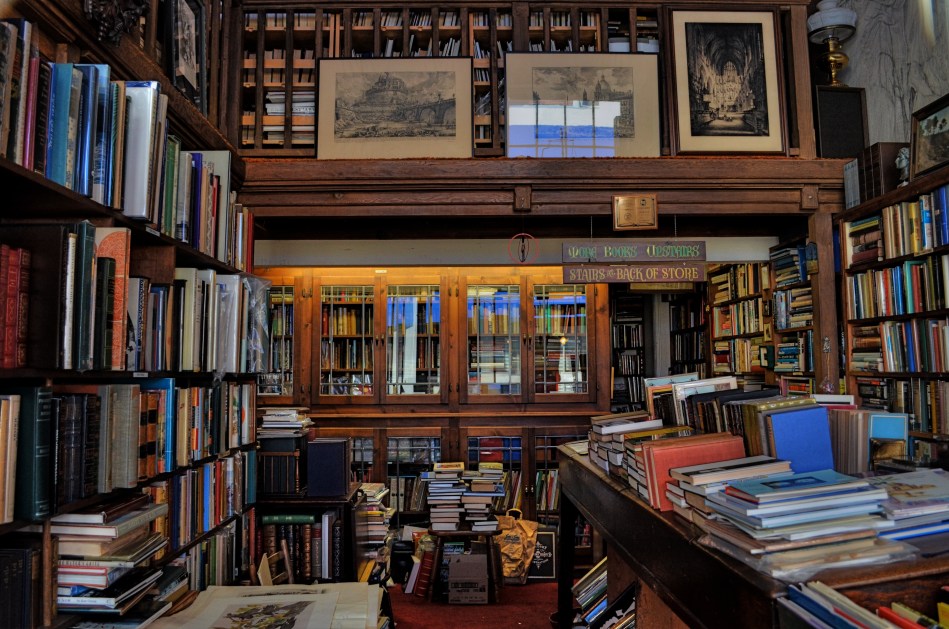

I WILL DO ANYTHING TO PHOTOGRAPH BOOKSTORES. Not the generic Costco and Wal-Mart bargain slabs laden with discounted bestsellers. Not the starched and sterile faux-library air of Barnes & Noble. I’m talking musty, dusty, crammed, chaotic collections of mismatched, timeless tomes…. “many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore” as Poe labeled them. I’m looking for places run by dotty old men with their glasses high on their forehead, cultural salvage yards layered in multiple stories of seemingly unrelated offerings in random stacks and precarious piles. Something doomed by progress, and beautiful in its fragility.

I almost missed this one.

Through the window, and into a forgotten world. A fake two-shot HDR from a single exposure at 1/80 sec., f/5, ISO 400, 18mm.

In my last post, I commented that, even when your photography is rules-based….i.e., always do this, never do that, there are times when you have to shoot on impulse alone and get what you can get. It sometimes begins when you’re presented with something you’re not, but should be, looking for. A few weeks ago, I was spending the afternoon at one of Monterey, California‘s most time-honored weekly rituals..the marvelous, multi-block farmers’ market along Alvarado Street. The sheer number of vendors dictates that some of the booths spill over onto the side streets, and that’s where I found The Book Haven. The interior of the store afforded an all-in-one view of its entire sprawling inventory, but the crush of tourists bustling in and out of its teeny front door meant that any image was going to look like the casting call for The Ten Commandments.

I had to come back, when both the store and I were alone.

With the limited amount of time I had in town, that meant that I would have to stroll by just hours ahead of my plane for home. Heading out at 8:30 in the morning, I had obviously solved the problem of “too many people in the picture”, but I had traded that hassle for a new one: the store would not be open for another three hours.

For the second time in a week (see “Look Through Any Window, Part One”) I was forced to shoot through a window, but at least there was enough light inside to illuminate nearly all of the store’s interior. To avoid a reflection, I would have to cram my lens right up against the glass. Once my autofocus stopped fidgeting, I could only obtain the framing I wanted by shooting through a narrow open place on the center of the front door, standing on tiptoe to hold the composition. I also had to keep the ISO dialed low enough to not create extra noise, but high enough so I could take a fairly fast handheld exposure and get as much detail from the dark corners as possible. Balancing act.

Let’s see what happens.

In viewing the image later, I saw that there wasn’t enough detail to suit me, either in the individual books or the darker spaces around the store, so I pulled a small cheat. Making a copy of the shot, I pulled down the contrast, boosted the exposure, and sucked out some shadow, then loaded both shots into Photomatix, fooling the HDR program into thinking they were two separate exposures. Photomatix is also a detail enhancer program, so I could add sharper textures to the books and a richer range of tones than were seen in the original through-the-window shot.

Hey, you can’t have it all, but, by at least trying, you get more than nothing.

And sometimes that’s everything.

Nice bookstore.

LOOK THROUGH ANY WINDOW, PART ONE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE COMMON THREAD ACROSS ALL THE PHOTO HOW-TO BOOKS EVER WRITTEN IS A WARNING: don’t let all the rules we are discussing here keep you from making a picture. Standardized techniques for exposure, composition, angle, and processing are road maps, not the Ten Commandments. It will become obvious pretty quickly to anyone who makes even a limited study of photography that some of the greatest pictures ever taken color outside the classical lines of “good picture making.” The war photo that captures the moment of death in a blur. The candid that cuts off half the subject’s face. The sunset with blown-out skies or lens flares. Many images outside the realm of “perfection” deliver something immediate and legitimate that goes beyond mere precision. Call it a fist to the gut.

The dawn creeps slowly in on the downtown streets of Monterey, California. A go-for-broke window shot taken under decidedly compromised conditions. 1/15 sec., f/3.5, ISO 640, 18mm.

Conversely, many technically pristine images are absolutely devoid of emotional impact, perfect executions that arrive at the finish line minus a soul. Finally, being happy with our results, despite how far they are from flawless is the animating spirit of art, and feeling. This all starts out with a boost of science, but it ain’t really science at all, is it? If it were, we could just send the camera out by itself, a heart-dead recording instrument like the Mars lander, and remove ourself from the equation entirely.

Thus the common entreaty in every instruction book: shoot it anyway. The only picture that is sure not to “come out” is the one you don’t shoot.

The image at left, of a business building in downtown Monterey, California was almost not taken. If I had been governed only by general how-to rules, I would have simply decided that it was impossible. Lots of reasons “not to”; shooting from a high hotel window at an angle that was nearly guaranteed to pick up a reflection, even taken in a dark room at pre-dawn; the need to be too close to the window to mount a tripod, therefore nixing the chance at a time exposure; and the likelihood that, for a hand-held shot, I would have to jack the camera’s ISO so high that some of the darker parts of the building would be the smudgy consistency of wet ashes.

Still, I couldn’t walk away from it. Mood, energy, atmosphere, something told me to just shoot it anyway.

I didn’t get “perfection”. That particular ideal had been yanked out of my reach, like Lucy pulling away Charlie Brown’s football. But I am glad I tried. (Click on the image to see a more detailed version of the result)

In the next post, a look at another window that threatened to hold a shot hostage, and a solution that rescued it.

Related articles

- 7 Ways to Inject More Creativity Into Your Photos (blogworld.com)

WHEN THE NOISE DIES

In the day, this place is a madness of color and noise. At night, you have its wonders all to yourself. Fisherman’s Wharf in Monterey, California. 25 second exposure at f/10, ISO 100, 24mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AMERICA IS A LOUD PLACE. IF WE DON’T HEAR NOISE WHEREVER WE GO, WE CREATE OUR OWN. It is a country whose every street rings with a cascade of counterpointed voices, transactions, signals, warnings, all of it borne on the madly flapping wings of sound. There are the obvious things, like car horns, screeching tires, soaring planes, thundering rails, somebody else’s music. And then there are the almost invisible hives of interconnecting lives that tamp vibration and confusion into our ears like a trash compactor.

We no longer even notice the noise of life.

In fact, we are vaguely thrown off-balance when it subsides. We need practice in remembering how to get more out of less.

That’s why I love long night exposures. It allows you to survey a scene after the madding crowd has left. Leaving for their dates, their destinies, their homes, they desert the fuller arenas of day and leave it to breathe, and vibrate, at a more intimate rhythm. Colors are muted. Shadows are lengthened. The sky itself becomes a deep velvet envelope instead of a sun-flooded backdrop.

The noise dies, and the quiet momentarily holds the field.

The above image is of Monterey’s Fisherman’s Wharf, one of the key tourist destinations in California, a state with an embarrassment of visual riches. During the day, it is a mash of voices, birdcalls, the deep croak of harbor seals, and the boardwalk come-ons of pitchmen hawking samples of chowder along the wharf’s clustered row of seafood joints. It is a colorful cacophony, but the serenity that descends just after dark on cold or inclement nights is worth seeking out as well.

Setting up a tripod and trying to capture the light patterns on the marina, I was stacking up a bunch of near misses. I had to turn my autofocus off, since dark subjects send it weaving all over the road, desperately searching for something to lock onto. I am also convinced that the vibration reduction should be off during night shots as well, since….and this is counter-intuitive….it creates the look of camera shake when it can’t naturally find it. Ow, my brain hurts.

The biggest problem I had was that, for exposures nearing thirty seconds in length, the gentle roll of the water, nearly imperceptible to the naked eye, was consistently blurring many of the boats in the frame, since I was actually capturing half a minute of their movement at a time. I couldn’t get an evenly sharp frame, and the cold was starting to make me wish I’d packed in a jacket. Then, out of desperation, I rotated the tripod about 180 degrees, and reframed to include the main cluster of shops along the raised dock near the marina. Suddenly, I had a composition, its lines drawing the eye from the front to the back of the shot.

More importantly, I got a record of the wharf’s nerve center in a rare moment of calm. People had taken their noise home, and what was left was allowed to be charming.

And I was there, for both my ear and my eye to “hear” it.

Thoughts?

Related articles

- Vibration Reduction (nikonusa.com)

WAITING FOR THE REVEAL

What lies beyond that door? Probably nothing to match the outside mood afforded to this forgotten delivery entrance by the onset of night. Hey, this is all about the magic, right? 15 second time-exposure, f/9, ISO 100, 20mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE’S A REASON BATMAN DOESN’T SWING THROUGH THE SKY AT HIGH NOON. Or that Shakespeare didn’t have his witches crowded around a cauldron during the mid-morning coffee break. And, of course, there are no love ballads bearing the title By The Light Of The Silvery…Sun. Mood is everything in photography and many subjects just don’t convey mystery or romance when brightly lit. This is no truer anywhere else than in the American southwest.

In Arizona, New Mexico, and California, there are plenty of places where the sun blazes away like a Hollywood klieg light during most of the day. The light is harsh, white, glaring. By mid-morning across the summer months most of the richer colors are blasted right out of the sky, and the only way to capture beauty is to wait for the hours warmed by low light.

Or no light.

I’ve always been a big believer in the transformation of familiar materials once night falls, and, going back to my old baby box camera days, I have always marveled at the simple miracle of holding a shutter open long enough to wring a few extra drops of light—just enough–from the deepening dark. I call it waiting for the reveal, and it never fails to serve up surprises.

One night last week, I was waiting on the sunset to fully finish behind a destination restaurant in Paradise Valley, Arizona (that’s really the name of the town…kind of like naming your city “Wonderfulville”). The front entrances and patios were gorgeous, of course, but after about a half hour I found myself getting restless with the utter postcardiness of it all. I was looking for something off the grid, forbidden even.

I found this door around the side of the resort, hidden by an overgrown, narrow walkway and illuminated by a single bleak bulb. As a location, especially in the daytime, this is no one’s idea of a choice spot. Except at this precise moment. It actually works better because of how much you can’t see, and I can’t justify shooting it at all, except that the reveal was working for me. And, while I liked the more conventional Chamber of Commerce shots I had taken earlier, there is something iffy and offbeat about this frame that I keep coming back to.

Sometimes the underdog is the best dog in the fight.

MAKE SOMETHING UP

Table-top romance gone wrong. Plastic Frank runs out on his clingy and equally plastic girlfriend. Shot on a tripod in darkness and light-painted with hand-held LED. 15 sec., 5/4.5, 30mm and, most importantly, since it’s a time exposure, stay at ISO 100. You’ll have plenty of light and keep the noise to a minimum.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE IS ONE PARTICULAR AREA WHERE, ALL AESTHETIC DEBATES ASIDE, DIGITAL BEATS FILM COLD. That, of course, is in the area of instantaneous feedback, the flexibility afforded to the shooter of adjusting his approach to a project “on the fly”. Simply stated, the shoot-check-adjust-shoot again workflow permitted by digital simply has to prevent more blown shoots and wasted opportunities than film. Shooting a tricky or rapidly changing subject with film can be honed to a pretty sure science, to be sure, especially given years of practice and a keenly trained eye on the part of the person behind the lens. However, a sizable gap of luck, or well-placed guesses remains, a gap narrowed by digital’s ability to speedily provide creative feedback. Release the hounds on me if this makes me a heretic, but as a lover of film, I still prefer the choices digital presents. I don’t have to hate horses to love automobiles.

The digital edge comes through to me especially in table-top shoots executed in darkness and illuminated with selectively “painted” light. I have already written on the general technique I use for these very strange projects in a post called Hello Darkness My Old Friend, so I won’t elaborate on that part again. What I will re-emphasize is that these kind of shots can only be arrived at through a lot of negative feedback, since hand-applied light sources produce drastically different results with every “pass” of the LED, or whatever your source of illumination may be. It’s also hard to find a shot that you love so much that you stop tweaking the process. The next shot just may afford you the quick flick of the wrist that will dramatically shift or redistribute shadows or re-jigger the highlighting of a surface feature.

Tends to fill up those rainy afternoons in a jiffy.

For the above image, I rescued two old dolls from the ash can for one more chance at fame. A friend who knew I was a lifelong Sinatra fan gifted me years ago with a beautifully detailed figure of Ol’ Blue Eyes in his trademark fedora and trench coat, the perfect get-up for hanging out underneath lonely, dim streetlights after all the bars have closed. The other figure is of course a Barbie, left behind when my stepdaughter headed off for college. Normally, these two characters wouldn’t exist in the same universe, and that was what struck me as fun to fool around with. I started to see Barbs as just one of a series of romantic conquests by The Voice on his way through the Universe of Total Coolness, with the inevitable bust-up happening on a dark street in the wee small hours of the morning.

For this shot, the idea was to light just enough of Frankie from above to suggest the aforementioned street lamp, accentuating the textures in his costume and the major angles of his face, without making his head glow so much as to underscore the fact that, duh, it’s made of plastic. The old Barbie had major hairdo issues, but hey, that’s why God made shallow focus. What I got wasn’t perfect, but then, it never is. The important thing with these projects is to make something up and make something come alive, to some degree.

Sadly, Barbie was probably the best thing that ever happened to the Chairman, something he’ll no doubt realize further down that long, lonesome road, looking for answers at the bottle of a shot glass. Hey, his loss.

So goodbye, babe and Amen / Here’s hoping we’ll meet now and then / It was great fun / But it was just one of those things…..

Related articles

- Swank or Rank? Frank Sinatra’s Former Penthouse Hits the Market for $7.7 M. (observer.com)

- tips for fun “everyday” photos. (eliseblaha.typepad.com)

- Hello Darkness My Old Friend (thenormaleye.com)

SUM OF THE PARTS

No one home? On the contrary: the essence of everyone who has ever sat in this room still seems to inhabit it. 1/25 sec., f/5.6, ISO 320, 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR ANNIE LIEBOVITZ, ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST INNOVATIVE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHERS, people are always more than they seem on the surface, or at least the surface that’s offered up for public consumption. Her images manage to reveal new elements in the world’s most familiar faces. But how do you capture the essence of a subject that can’t sit for you because they are no longer around…literally? Her recent project and book, Pilgrimage, eloquently creates photographic remembrances of essential American figures from Lincoln to Emerson, Thoreau to Darwin, by making images of the houses and estates in which they lived, the personal objects they owned or touched, the physical echo of their having been alive. It is a daring and somewhat spiritual project, and one which has got me to thinking about compositions that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Believing as I do that houses really do retain the imprint of the people who lived in them, I was mesmerized by the images in Pilgrimage, and have never been able to see a house the same way since. We don’t all have access to the room where Virginia Woolf wrote, the box of art chalks used by Georgia O’ Keefe, or Ansel Adams’ final workshop, but we can examine the homes of those we know with fresh eyes, finding that they reveal something about their owners beyond the snaps we have of the people who inhabit them. The accumulations, the treasures, the keepings of decades of living are quiet but eloquent testimony to the way we build up our lives in houses day by day, scrap by personal scrap. In some way they may say more about us than a picture of us sitting on the couch might. At least it’s another way of seeing, and photography is about finding as many of those ways as possible.

I spent some time recently in a marvelous old brownstone that has already housed generations of owners, a structure which has a life rhythm all its own. Gazing out its windows, I imagined how many sunrises and sunsets had been framed before the eyes of its tenants. Peering out at the gardens, I was in some way one with all of them. I knew nothing about most of them, and yet I knew the house had created the same delight for all of us. Using available light only, I tried to let the building reveal itself without any extra “noise” or “help” from me. It made the house’s voice louder, clearer.

We all live in, or near, places that have the power to speak, locations where energy and people show us the sum of all the parts of a life.

Thoughts?

OPTING FOR IMPERFECTION

When additional detail needs to be extracted from shadows and from the texture of materials, HDR (High Dynamic Range) is a great solution. This shot of the entrance to the New York Public Library is a three-exposure bracket composited in Photomatix. Is this process great for all images of the same subject? See a different approach below….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

SOMETIMES I LOSE MY WAY, CREATIVELY. Given that cameras are technical devices and not creative entities, we all do. We have been given, in today’s market, wonderful aids to seeing and interpreting what we consider noteworthy. Technological advances are surging so swiftly in the digital era that we are being given scads of pre-packaged effects that are baked into the brains of our cameras, ideally designed to help us calculate and fail less, succeed and create more. To that end, we are awash in not only genuinely beneficial shortcuts like programmable white balance and facial recognition, but “miniature”, sketch, selective desaturation, and, recently, in-camera HDR options as well. Something of a tipping point is occurring in all this, and maybe you feel it as strongly as I do; more and more of our output feels like the camera, the toys, the gimmicks are dictating what gets shot, and what it finally looks like.

Here’s the nugget in all this: I have been wrestling with HDR as both a useful enhancer and a seductive destroyer for about three years now. Be assured that I am no prig who sees the technique as unworthy of “pure” photography. Like the old masters of burning and dodging, multiple exposure, etc., I believe that, armed with a strong concept, you use whatever tool it takes to get the best result. And when it comes to rescuing details in darker patches, crisping up details in certain materials like brick and stone, and gently amplifying color intensity, HDR can be a marvelous tool. Where it becomes like crack is in coming to seem as if it is the single best gateway to a fully realized image. That is wrong, and I have more than a few gooey Elvis-on-black-velvet paintings that once had a chance to be decent pictures, before they were deep-fried in the conceptual Crisco of bad HDR. Full disclosure: I also have a few oh-wow HDR images which delivered the range of tone and detail that I honestly believe would have been beyond my reach with a conventional exposure. The challenge, as always, is in not using the same answer to every situation, and also to avoid using an atomic bomb to swat a fly.

Same library, different solution: I could have processed this in HDR in an attempt to pluck additional detail from the darker areas, but after agonizing over it, I decided to leave well enough alone. The exposure was a lucky one over a wide range of light, and it’s close enough to what I saw without fussing it to death and perhaps making it appear over-baked. 1/30 sec., f/6.3, ISO 320, 18mm.

Recently, I am looking at more pictures that are not, in essence, flawless, and asking, how much solution do I need here? How much do I want people to swoon over my processing prowess versus what I am trying to say? As a consequence, I find that images that I might have reflexively processed in HDR just a few weeks ago, are now agonized over a bit longer, with me often erring on the side of whatever “flaws” may be in the originals. Is there any crime in leaving in a bit more darkness here, a slight blowout in light there, if the overall result feels more organic, or dare I say, more human? Do we have to banish all the mystery in a shot in some blind devotion to uniformity or prettiness?

I know that it was the camera, and not me, that actually “took” the picture, but I have to keep reminding myself to invest as much of my own care and precision ahead of clicking the shutter, not merely relying on the super-toys of the age to breathe life into something, after the fact, that I, in the taking, could not do myself. I’m not swearing off of any one technique, but I always come back to the same central rule of the best kind of photography; do all your best creative work before the snap. Afterwards, all your best efforts are largely compensation, compromise, and clean-up.

It’s already a divine photographic truth that some of the best pictures of all time are flawed, imperfect, incomplete. That’s why you go back, Jack, and do it again.

The journey is as important as the destination, maybe more so.

Thoughts?

Related articles

HELLO DARKNESS MY OLD FRIEND

This still life, designed to recall the “cold war” feel of the tape recorder and other props, was shot in a completely darkened room, and lit with sweeps and stabs of light from a handheld LED, used to selectively create the patterns of bright spots and shadows. Taken at 19 seconds, f/6.3, ISO 100 at 50mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

MOST OF THE PICTURES WE TAKE involve shaping and selecting details from subjects that are already bathed, to some degree, in light. “Darkness” is in such images, but it resides peripherally in the nooks and crannies where the light didn’t naturally flow or was prevented from going. Dark is thus the fat that marbles the meat, the characterizing texture in a generally bright palette of colors. It is seasoning, not substance.

By contrast, shooting that begins in total darkness means entering a realm of mystery, since you start with nothing, a blank and black slate, onto which you selectively import some light, not enough to banish the dark, but light that suggests, implies, hints at definition. For the viewer, it is the difference between the bright window light of a chat at a mid-afternoon cafe and the intimacy of a shared huddle around a midnight campfire. What I call “absolute night” shots are often more personal work than just managing to snap a well-lit public night spot like an urban street or an illuminated monument after dusk. It’s teaching yourself to show the minimum, to employ just enough light to the tell the story, and no more. It is about deciding to leave out things. It is an editorial, rather than a reportorial process.

The only constants about “absolute dark” shooting are these:

You need a tripod-mounted camera. Your shutter will be open as long as it takes to create what you want, and far longer than you can hope to hold the camera steady. If you have a timer and/or a remote shutter release, break those out of the bag, too. The less you touch that camera, the better. Besides, you’ll be busy with other things.

Set the minimum ISO. If you’re quickly snapping a dark subject, you can compromise quality with a higher and thus slightly noisier ISO setting. When you have all the time you need to slowly expose your subject, however, you can keep ISO at 100 and banish most of that grain. Some cameras will develop wild or “hot” pixels once the shutter’s open for more than a minute, but for many hand-illuminated dark shots, you can get what you need in far less than that amount of time.

Use some kind of small hand-held illumination. Something about the size of a keychain-sized LED, with an extremely narrow focus of very white light. Pick them up at the dollar store and get a model that works well in your hand. This is your magic wand, with which, after beginning the exposure in complete darkness, you will be painting light onto various parts of your subject, depending on what kind of effect you want. Get a light with a handy and responsive power switch, since you may turn the light on and off many times during a single exposure.

You can use autofocus, even in manual mode, but compose and lock the focus when all the room lights are on. Set it, forget it, douse the power and get to work.

Which brings us to an important caveat. Even though you are avoiding the absolute blast-out of white that would result if you were using a conventional flash, lingering over a particular contour of your subject for more than a second or so will really burn a hot spot into its surface, perhaps blowing out an entire portion of the shot. Best way to curb this is to click on, paint, click off, re-position, click back on and repeat the sequence as needed. Another method could involve making slow but steady passes over the subject….back and forth, imagining in your mind what you want to see lit and what you want to remain dark. It’s your project and your mood, so you’ll want to shoot lots of frames and pause between each exposure to adjust what you’re doing, again based on what kind of look you’re going for.

Beyond that, there are no rules, and, over the course of a long shoot, you will probably change your mind as to what your destination is anyhow. No one is getting a grade on this, and the results aren’t going in your permanent file, so have fun with it.

Also shot in a darkened room, but with simpler lighting plan and a shorter exposure time. The dial created its own glow and a handheld light gave some detail to the grillwork. 1/2 sec., 5/4.8, ISO 100, 32mm.

Some objects lend themselves to absolute night than others. For example, I am part of the last generation that often listened to radio in the dark. You just won’t get the same eerie thrill listening to The Shadow or Inner Sanctum in a gaily lit room, so, for the above image of my mid-1930’s I.T.I. radio, I wanted a somber mood. I decided to make the tuning dial’s “spook light” my primary source of interest, with a selective wash of hand-held light on the speaker grille, since the dial was too weak (even with a longer exposure) to throw a glow onto the rest of the radio’s face. Knobs are less cool so they are darker, and the overall chassis is far less cool, so it generally resides in shadow. Result: one ooky-spooky radio. Add murder mystery and stir well.

Flickr and other online photo-sharing sites can give you a lot of examples on what subjects really come alive in the dark. The most intoxicating part of point-and-paint lighting is the sheer control you have over the process, which, with practice, is virtually absolute. Control freaks of the world rejoice.

Head for the heart of darkness. You’ll be amazed what you can see, or, better yet, what you can enable others to see.

Thoughts?

NOTE: If you wish to see comments on this essay, click on the title at the top of the article and they should be viewable after the end of the post.

Related articles

- Lighting Techniques: Light Painting (nikonusa.com)

- Light Writing (cutoutandkeep.net)

SPLITTING THE DIFFERENCE

Really dark church, not much time. An HDR composite of just two exposures to refrain from trying to read the darkest areas and thus keep extra noise out of the final image. Shot at 1/15 and 1/30 sec., both exposures at f/5.6, a slight ISO bump to 200 at 18mm. Far from perfect but something less than a total disaster with an impatient tour group wondering where I wandered off to.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE MOST EXASPERATING WORDS HEARD ON VACATION: Everyone back on the tour bus.

Damn. Okay, just a second.

Now. We’re going NOW.

I’ve almost got it (maybe a different f-stop….? …..no, I’m just standing in my own light….here, let’s try THIS….

I mean it, we’re leaving without you.

YES, right there, seriously, I’m right behind you. Read a brochure will ya? Geez, NOTHING’S working…….

Sound remotely familiar? There seems to be an inverse proportion of need-to-result that happens when an entire group of tourists is cursing your name and the day you ever set eyes on a camera. The more they tap their collective toe wondering what’s taking so looooong, the farther you are away from anything that will, even for an instant, give you a way to get on that bus with a smile on your face. It’s like the boulder is already bearing down on Indiana Jones, and, even as he runs for his life, he still wonders if there’d be a way to go back for just one more necklace….

Dirty Little Secret: there is no such thing as a photo “stop” when you are part of a traveling group. At best it’s a photo “slow down” unless you literally want to shoot from the hip and hope for the best, which doesn’t work in skeet shooting, horseshoes, brain surgery, ….or photography. Dirty Little Secret Two: you are only marginally welcome at the tomb or cathedral or historically awesome whosis they’re dragging you past, so be grateful we’re letting you in here at all and don’t go all Avedon on us. We know how to handle people like you. We’re taking the next delay out of your bathroom break, wise guy.

A recent trip to the beautiful Memorial Church at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California was that latest of many “back on the bus” scenarios in my life, albeit one with a somewhat happy outcome. Dedicated in 1903 by the surviving widow of the school’s founder, Leland Stanford, the church loads the eye with borrowed styles and decorous detail from a half-dozen different architectural periods, and yet, is majestic rather than noisy, a tranquil oasis within a starkly contemporary and busy campus. And, within seconds of having entered its cavernous space as part of a walking campus tour, it becomes obvious that it will be impossible to do anything, image-wise, other than selecting a small part of the story and working against the clock to make a fast (prayerful) grab. No tripods, no careful contemplation; this will be meatball surgery. And the clock is ticking now.

So we ducked inside. With many of the church’s altars and alcoves shrouded in deep shadow, even at midday, choices were going to be limited. A straight-on flash was going to be an obscene waste of time, unless I wanted to see a blown-out glob of white, three feet in front of me, the effect of lighting a flare in a cave. Likewise, bumping my Nikon’s ISO high enough to read a greater amount of detail was going to be a no-score, since the inner darkness was so stark, away from the skylight of the central basilica dome, that I was inviting enough noise to make the whole thing look like a kid’s smudged watercolor. No, I had to find a way to split the difference; Show some of the light and let the darkness alone.

Instead of bracketing anywhere from 3 to 5 shots in hopes of creating a composite high dynamic range image in post production, I took a narrower bracket of two. I jacked the ISO for both of them just a bit, but not enough to get a lethal grunge gumbo once the two were merged. I shot for the bright highlights and tried to compose so that the light’s falloff would suggest the detail I wouldn’t be able to actually show. At least getting a good angle on the basilica’s arches would allow the mind to sketch out the space that couldn’t be adequately lit on the fly. For insurance, I tried the same trick with several other compositions, but by that time my wife was calling my cel from outside the church, wondering if I had fallen into the baptismal font and drowned.

Yes, right there, I’m coming. Oh, are you all waiting for me? Sorry…..

Perhaps its the worst kind of boorish tourism to forget that, when the doors to the world’s special places are opened to you, you are an invited guest, not some battle-hardened newsie on deadline for an editor. I do really want to be nice. However, I really want to go home with a picture,too, and so I remain a work in progress. Perhaps I can be rehabilitated, and, for the sake of my marriage, I should try.

And yet.

Related articles

- The Ultimate Guide to HDR Photography (pixiq.com)

BEYOND THE THING ITSELF

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU NO DOUBT HAVE YOUR OWN “RULES” as to when a humble object becomes a noble one to the camera, that strange transference of energy from ordinary to compelling that allows an image to do more than record the thing itself. A million scattered fragments of daily life have been morphed into, if not art, something more than mundane, and it happens in an altogether mysterious way somewhere between picking it and clicking it. I don’t so much have a list of rules as I do a sequence of instincts. I know when I might have stumbled across something, something that, if poked, prodded or teased out in some way, might give me pleasure on the back end. It’s a little more advanced than a crap shoot and a far cry from science.

With still life subjects, unlike portraits or documentary work. there isn’t an argument about the ethics or “purity” of manipulating the material….rearranging it, changing the emphasis, tweaking the light. In fact, still lifes are the only kinds of pictures where “working it” is the main objective. You know you’re molding the material. You want to see what other qualities or aspects you can reveal by, well, kind of playing with your food. It’s like Richard Dreyfuss shaping mashed potatoes into the Devil’s Tower.

If I have any hard and fast rule about still lifes, it may be to throw out my trash a little slower. I can recall several instances in which I was on my way the garbage can with something, only to save it from oblivion at the last minute, turn it over on a table, and then try to tell myself something new about it from this angle or that. The above image, taken a few months ago, was such a salvage job, and, for reasons only important to myself, I like what resulted. Hey, Rauschenburg glued egg cartons on canvas. This ain’t new.

My wife had packed a quick fruit and nut snack into a piece of aluminum foil, forgot to eat it, and brought it back home in her lunch sack. In cleaning out the sack, I figured she would not want to take it a second day and started to throw it out. Re-wrapped several times, the foil now had a refractive quality which, in conjunction with window light from our patio, seemed to amp up the color of the apple slice and the almonds. Better yet, by playing with the crinkle factor of the foil, I could turn it into a combination reflector pan and bounce card. Five or six shots worth of work, and suddenly the afternoon seemed worthwhile.

I know, nuts.

Fruits and nuts, to be exact. Hey, if we don’t play, how will we learn to work? Get out on the playground. Make the playground.

And inspect your trash as you roll it to the curb.

Hey, you never know.

Thoughts?

GOING FOR BROKE

Some people are over the whole “art” thing. Certainly this cynical fellow has seen it all. I used a primitive flash bounce to illuminate his darkened features. 1/40 sec., f/5, ISO 500, 22mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE READ MORE THAN A FEW ARTICLES OF LATE by professional photographers who confess that they occasionally get stuck in teaching mode, even to the detriment of their own love of shooting. One such author went to far as to recall a recent concert he had attended, camera-less, only to observe, with snotty amusement, the attempts of a young woman to capture action on the far-off stage area. His first reaction was to disdain not only her limited camera but to catalogue all her most heinous errors in composition, exposure, and use of flash, as he mentally predicted how poor her results would be and how she was, essentially, wasting her time.

Then something shifted in his thinking. Instead of being depressed at what hadn’t worked, the woman’s energy revealed that she was actually making the most of the moment; learning, through trial and error, what to do or not do in future. At the end of his essay, he came to realize that “she is a better photographer than me”, since she was taking risks, pushing the limits of her own skills, and developing her craft, one frame at a time, while he had left his own camera at home and was learning nothing. His point hit home with me, since it is a recurring theme of this blog and a key belief among those I respect most in the imaging world.

In brief:

Shoot. Shoot some more. Dare to fail. Be willing to take more “bad” pictures than the next guy. Get your head out of academic minutia and into the doing of it. Screw up, suck up, but above all, show up.

Ready to play.

Sometimes, just the sheer unwillingness to go home empty-handed provides you with real delight. Last week, I was making the rounds at an area gallery district, the type that does nightly “art walks” as a way of speed-dating potential customers. Many of the best shots I get in these surroundings are near or just after dark, and I always like peeping into the windows of shuttered businesses at night, since some key character of light and mood invariably occurs. For the shot shown above, I fell in love with one gallery that had a kind of sentry posted outside, in the form of an enormous sculpted head. Its aloof expression reminded me of a cross between Easter Island and Blue Man Group, and I really wanted him/her/it to be a part of the shot. However, I had not brought an external flash unit with me, and the sculpture was reading 100% dark in contrast to the interior of the gallery. I was desperate, but not desperate enough to use straight-on pop-up flash, which would have blown the face out completely and destroyed any chance at a moody feel.

Time to improvise.

Having left my bounce card at home as well (I was on foot and truly traveling light), I noticed that the head was underneath a low over-hanging porch roof, something you just must have on the front of an Arizona business in summer. Going totally into what-the-hell mode, I stuck my flat left hand just under the bottom of the pop-up flash and angled it upward about 15 degrees to create a crude bounce off the roof ceiling, allowing the light to soften as it came down upon the top of the head. It took a few tries to avoid creating an uber-white Aurora Borealis effect on the ceiling, and I had to move my feet around to figure out how to get some of the light to cascade down the head’s front and illuminate its features. I also had to bump the ISO up a bit to compensate for the fall-off in the flash at the distance I was standing, but, at the end, I at least got something. Moreover, like the woman at the concert, what I had picked up in technique more than compensated me for the fact that the shot wasn’t strictly an award winner.

I have been playing around with primitive flash bouncing for a while now, and the results run the gamut from god-awful to glad-I-did-that. But it’s all a win no matter how each individual shot plays out, because every image brings me closer to the cumulatively evolved instinct that, someday, will give me great pictures. The baby will eventually be born, but the midwife has to do the front-end work. Nothing I will ever shoot will be captured under perfect conditions, so why drop dead of old age waiting for that to happen? We’re almost to the end of Century Two in this game of writing with light, and all the easy pictures have already been shot, so what’s left will have to be hewed out by hand.

I suggest that we occasionally get our nose out of books (and, duh, blogs too) and start carving.

180 DEGREES

This image, the reason I ventured out into the night, originally eluded me, causing me to turn a half circle to discover a totally different scene and feel waiting just over my shoulder. 20 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 20mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I WISH I HAD A LEICA for every time I came away from a shooting project with something completely opposite from the prize I was originally seeking. The odd candid moment, the last-minute change of light, the bizarre intervening event….there are so many random factors even in the shots that are the most meticulously planned that photography is kept perpetually fresh, since it is absolutely impossible to ensure its end results, especially for infants playing at my level. That point was dramatically brought home to me again a few weeks ago, and all I had to do was turn my head 180 degrees.

All during a week’s stay at a conference center near Yosemite National Park, I had been struck by how the first view a visitor got of the main lodge and its surrounding pond, from an approach road slightly above the building, was by far a better framing of the place than could be had anywhere else on the grounds. A few days of strolling by the lodge from several approaches had not provided any better staging of the quiet scene, but, with the harshness of the daylight at that altitude, I was convinced that a long exposure done just after nightfall would convey a more peaceful, intimate mood than I could ever hope to capture by day. And so, on the evening before I was to leave the lodge for home, I decided to take my tripod to the approach road and set up for a try.

The road is rather twisty and narrow, and so its last turn before heading for the lodge’s parking areas is lit with a street lamp, and a bloody bright one at that. It’s a sodium vapor light, which registers very orange to the eye. I’m used to these monsters, since, back home in Phoenix, they are the predominant city light sources, creating less long-distance “light pollution” for astronomers in Flagstaff trying to see the finer features in the night sky. At any rate, the road was so bright that I had to set up closer to the lodge than originally planned in order to avoid a lot of ambient light over my shoulder killing the subdued dark I wanted for my shot. Intervening event and last-minute change of light. Changing my stance, I was also having problems with movement on the pond surface. It was a tad too swift to allow for a mirroring of the lodge, and a long exposure was going to soften it up even more. I was going to get pretty colors, but they would be diffuse and gauzy rather than reflective. At the same time I was trying to avoid framing another lamp, this one to the right of the lodge. Illuminating a walking path, it would, over the length of the exposure, pretty much burn its way into the scene and distract from the impact. Typical problems, but I was already losing my love for the project, and after about a half-dozen flubbed attempts, I was trying to avoid mouthing several choice Anglo-Saxon epithets.

It was the need to take a break that had me looking around to see if anything else could be done under the conditions, and that’s when I turned my head to really see the light from the approach road that had been over my shoulder. Candid moment. Now I saw that orange light illuminating the road, the rustic fence, and the surrounding trees and shrubs in an eerie, Halloween-ish cast. The same scene in daylight or natural color would have registered just as “some nice trees”, but now it was Sleepy Hollow, the scary walk home after the goblins come out, the place where evil things breed. Better yet, if I stepped just about six inches to the right of where I was standing, the hated lamp-post would be totally obscured by the largest tree in the shot, casting its shadow another 20 or so feet longer and serving up a little added drama as a bonus. Suddenly, the lamp had been transformed from a fiend to a friend. I swiveled the tripod’s head around, set the shot, and got where I needed to be in two clicks.

After first trying (and failing) to nail the image of the lodge, I pivoted around and found this scene, which had been waiting to be discovered right behind me. Once I shot this, I turned around and made one more attempt on the lodge, using, as it turned out, the exact same setting as this picture; 20 sec., f/8, ISO 100, 20mm.

Better yet, the break in the action allowed me to re-boot my head vis-a-vis the lodge image. I turned back around, and, oddly, with the exact same exposure settings, hit a balance I could live with. Neither shot was perfect, but the creation of one had actually enabled the capture of the other. On the walk back to my cabin, I was already dissecting the weaknesses in both, but they each, in turn, had taught me, again, the hardest lessons, for me, in photography. Slow down. Look. Think. Plan, but don’t be afraid of reactive instinct. Sometimes, a sacred plan can keep you from “getting the picture”, figuratively and literally.

All I have to do is remember to turn my head around.