JOY GENERATORS

I could pose this rascal all day long, but I can’t create what he can freely give me. 1/40 sec., f/3.2, ISO 500, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S A TITANIC CLICHE, BUT RESOUNDINGLY TRUE: if you want a child to reveal himself to you photographically, get out of his way.

The highly profitable field of child portrait photography is being turned on its head, or more precisely, turned out of the traditional portrait studio, by the democratization of image making. As technical and monetary barriers that once separated the masses from the elite few are vanishing from photography, every aspect of formal studio sittings is being re-examined. And that means that the $7.99 quickie K-Mart kiddie package is going the way of the dodo. And it’s about bloody time.

Making the subject fit the setting, that is, molding someone to the props, lighting or poses that are most convenient to the portraitist seems increasingly ridiculous. Thing is, the “pros” who do portrait work at the highest levels of the photo industry have long since abandoned these polite prisons, with Edward Steichen posing authors, politicians and film stars in real-life settings (including their own homes) as early as the 1920’s, and Richard Avedon pulling models out of the studio and into the street by the late 1940’s. So it’s not the best photographers who insist on perpetuating the restrictive environment of the studio shoot.

No, it’s the mills, the department and discount stores who still wrangle the kiddies into pre-fab backdrops and watch-the-birdie toys, cranking out one bland, safe image after another, and veering the photograph further and further from any genuine document of the child’s true personality. This is what has to change, and what will eventually result in something altogether different when it comes to kid portraiture.

Children cannot convey anything real about themselves if they are taken out of their comfort zones, the real places that they play and explore. I have seen stunning stuff done with kids in their native environment that dwarfs anything the mills can produce, but the old ways die hard, especially since we still think in terms of “official” portraits, as if it’s 1850 and we have a single opportunity to record our existence for posterity. There really need be no “official” portrait of your child. He isn’t U.S. Grant posing for Matthew Brady. He is a living, pulsating creature bent on joy, and guess what? You know more about who and what he is than the hourly clown at Sears.

I believe that, just as adult portraiture has long since moved out of the studio, children need also to be released from the land of balloons and plush toys. You have the ability to work almost endlessly on getting the shots of your children that you want, and better equipment for even basic candids than have existed at any other period in history. Trust yourself, and experiment. Stop saying “cheese”, and get rid of that damned birdie. Don’t pose, place, or position your kids. Witness these little joy generators in the act of living. They’ll give you everything else you need.

STEALTH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AT A PARTY, THERE ARE DISTINCT ADVANTAGES TO NOT BEING AN “OFFICIAL” PHOTOGRAPHER. You could probably catalogue many of them yourself with no strain. Chief among the perks of being an amateur (can we get a better word for this?) is that you are the captain of your own fate. You shoot what you want, when you want. Your arrival on the scene is not telegraphed by stacks of accompanying cases, light fixtures, connecting cords or other spontaneity killers that are essential to someone who has been “assigned” to an event. Your very unimportance is your license to fly, your ticket to liberation. Termed honestly (if unkindly), your work just doesn’t matter to anyone else, and so it can mean everything to you. Yay.

One of the supreme kicks I derive from going to events with my wife is that I can make her forget I’m there. I mean, as a guy with a camera. She has the gift of being able to submerge completely into the social dynamics of wherever she is, so she is not thinking about when I may elect to sneak up and snap her. Believe me, when you live with a beautiful woman who also hates to have her picture taken, this is like hitting the trifecta at Del Mar. At 20 to 1.

Free from the constraints of being “on the job”, I enjoy a kind of invisibility at parties, since I use the fastest lenses I can and no flash, ever, ever, ever. I do not call attention to myself. I do not exhort people to smile or arrange them next to people that they may or may not be able to stand. The word “cheese” never leaves my lips. I take what the moment gives me, as that is often richer than anything I might concoct, anyway. Working with a DSLR is a little more conspicuous than the magical invisibility of a phone camera, which people totally ignore, but if I am cagey, I can work with an “official” camera and not be perceived as a threat. Again, with a woman who (a) looks great and (b) doesn’t like how she looks in pictures, this is nirvana.

Candid photography is all about the stealth. It’s not about warning or prepping people that, attention K-Mart shoppers, you’re about to have your picture took. The more you insert yourself into the process (look over here! big smiiiiile!) the more you interrupt the natural rhythm that you set out to capture. So stop working against yourself. Be a happy sneak thief. Like me.

THE UNRESOLVED RIDDLE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A RECENT PIECE BY TIMOTHY EGAN IN THE NEW YORK TIMES decried the latest innovation in Instagram etiquette, a device called a “selfie stick”. As the name implies, the stick is designed to hold one’s smartphone at a modest distance from its subject (me!) allowing oneself to be better framed against larger scenes, such as landscapes, local sights, etc. Egan mostly ranted against the additional invasion of public peace by armies of narcissistic simps who couldn’t be persuaded to merely be in the moment, unless they could also be in the picture. It struck him as a fresh assault on “real” experience, another example, as if we needed one, of our sadly self-absorbed age.

I agree with most of Egan’s epistle, but I think the real tragedy is that the selfie stick allows us to take more, more, more pictures, and reveal less, less, less of the people that we truly are. Selfies are more than emotionally stunted; most of them are also lies, or, more properly, masks. They are not “portraits” any more than they are steam shovels, as they merely replicate our favorite way of distancing ourselves from discovery… the patented camera smile. Frame after frame, day after endless day, the tselfie tsunami pushes any genuine depiction of humanity farther away, substituting toothpaste grins for authentic faces. Photographs can plumb the depths of the spirit, or they can put up an impenetrable barrier to its discovery, like the endless string of forced “I was here” shots that we now endure in every public place.

There’s a reason that the best portraits begin with not one lucky snap but dozens of “maybes”, as subject and photographer perform a kind of dance with each other, a slow wrestling match between artifice and exposition. Let’s be clear: just because it is easier,mechanically, to capture some kind of image of ourselves doesn’t mean we are getting any closer to the people we camouflage beneath carefully crafted personae. Indeed, if a person who acts as his own lawyer “has a fool for a client”, then most of us have a liar in charge of telling the truth about ourselves. Merely larding on additional technology (say, a stick on a selfie) just allows a larger portion of our false selves to fit into the picture, while the puzzle of who that person is, smirking into the camera, remains, all too often, an unresolved riddle.

THE EYES (DON’T NECESSARILY) HAVE IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A QUICK GOOGLING OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC UNIVERSE THESE DAYS will turn up a number of sites dedicated to “faceless portraits”, if there can, strictly speaking, be such a thing (and I believe there can). In a recent post entitled Private, Not Impersonal, I explored the phenomenon in which photographers, absent the features that most easily chronicle their subjects’ personalities, imply them, merely through body language, composition, or lighting. At the time I wrote the post, I was unaware how widespread the practice of faceless portraits had become. In fact, it’s something of a rage. Hmm. The very thought that, even by accident, I could be aligned with something hip, is, by turns, both terrifying and hilarious.

Thing is, photographs, as the famous curator John Szarkowki remarked, both conceal and reveal, and there is nothing about the full depiction of a human face that guarantees that you’re learning or knowing anything about the subject in frame. We are all to practiced at maintaining our respective masks for many portraits to be taken, ha ha, at face value. Cast your eye back through history and you will find dozens of compelling portraits, from Edward Steichen’s silhouettes of Rodin to Annie Leibovitz’ blurred dance photos of Diane Keaton, that preserve some precious element of humanity that a formal, face-on sitting cannot deliver. Call it mystery, for lack of a more precise word.

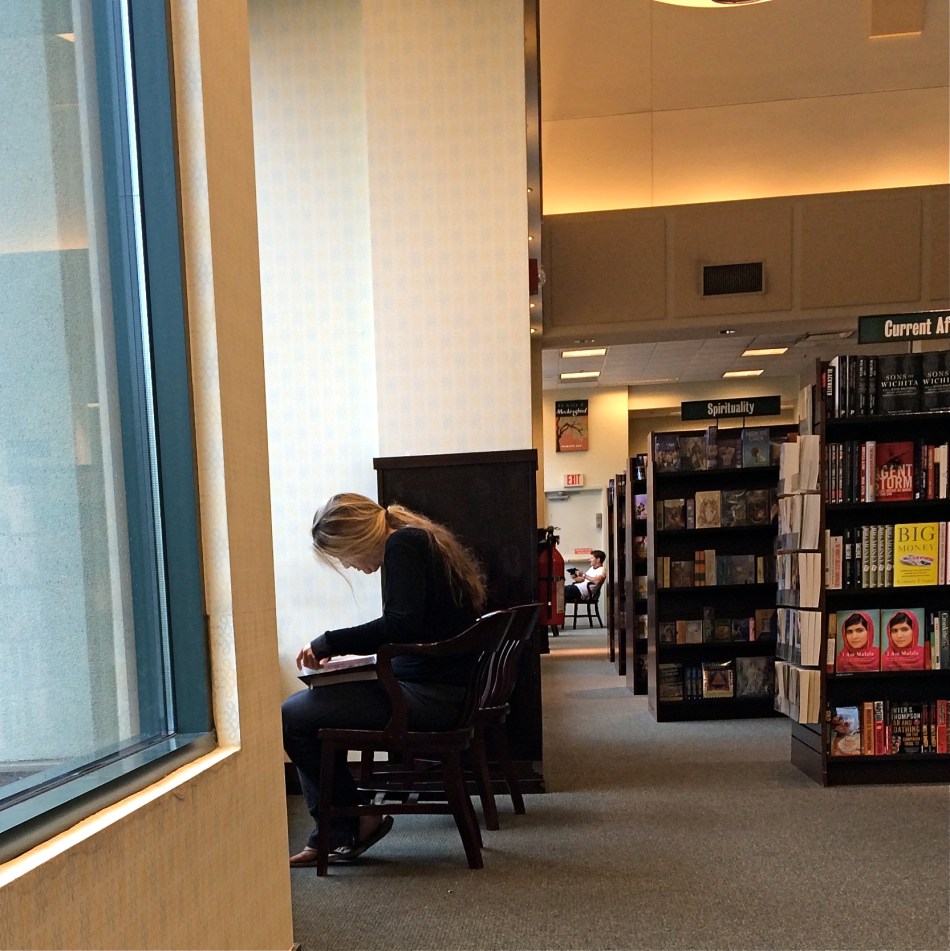

In the above frame, the subject whose face I myself never even saw gave me something wonderfully human, about reading in particular, but about enchantment in general. She is furiously busy discovering another world, a world the rest of us can only guess at, seeping up from her book. Her entire body is an inventory of emotional textures…of relaxation, attentiveness, of both being in the present and so completely someplace else. Framing her to include the negative spaces of the window, the carpet and the wider bookstore isolate her further from us, but not in a negative way. She wants to be apart; she is on a journey.

My “girl with the flaxen hair” was unaware of me, and I shot furtively and quickly to make sure I didn’t break the spell she was under. It was the least I could do in gratitude for a chance to witness her adventure. Looking back, I think she provided more than enough magic without revealing a single fragment of her face. Seeing is selecting, and I had been given all I needed to do both.

Click and be gone.

PRIVATE, NOT IMPERSONAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PORTRAITURE IS RATHER NARROWLY DEFINED BY MOST PHOTOGRAPHERS as an interpretation of a person’s face, the place wherein we believe that most of his/her humanity resides. The wry smile. The upturned eyebrow. The sparkling eye. It’s all there in the features, or so we seem to profess by valuing the face over nearly all other physical features.We stipulate that there are notable exceptions where the body carries most of the message, as in crowd scenes, sports action, or combat shots. But for the most part, we let the face hold the floor (and believe me, after a few misspent nights, my face has held the floor plenty of times).

It’s interesting, however, in an age where privacy has become a premiere issue, and in which the camera’s eye never blinks, that we don’t explore the narrative power of bodies as much as we do faces. The body, after all, carries out the intentions of the mind no less than does the face. It executes the physical action that the mind intends, and so creates a space that reveals that intention. Just like a face. And yet, we have a decidedly pro-face bias in our portraiture, to the point that a portrait that does not include a face is thought by some not to be a portrait at all.

But let’s keep the discussion, and our minds, open, shall we? I love to work with random crowds, and I like nothing better than to immortalizing emotions in a nice face-freeze. However, I strongly maintain that, absent those obvious visual “cues”, a body can carry a storyline all by itself, even enhance the charm or mystery involved in trying to penetrate the personality of our subjects.

Consider for a moment how many amazing nude studies you’ve seen where the subject’s face is completely, even deliberately obscured. Does the resulting image lack in power, or does the power traditionally residing in the face just transfer to the rest of the composition?

Portraits (I insist on calling them that) that are more “private” for being faceless are no more “impersonal” than if the subject was flashing the traditional “cheese!” and beaming their personality directly into the lens.

Photography is not about always getting the vantage point that we want, but maximizing the one we have at hand. And sometimes, taking away a face also strips away a mask. But beyond that, why not actually court mystery, allow ourselves to trust our audiences to supply mentally what we reserve visually?

Ask yourself: what does a photograph of understatement look like?

SUBMERGED IN BEING

Cropped and enhanced from a group shot. I could sit this young woman in a studio for a thousand years and not get this expression.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CANDID PORTRAITURE IS VOLATILE, THE DEAD OPPOSITE OF A FORMAL SITTING, and therefore a little scarier for some photographers. We tell ourselves that we gain more control over the results of a staged portrait, since we are dictating so many terms within it…the setting, the light, the choice of props, etc. However, can’t all that control also drain the life out of our subjects by injecting self-consciousness ? Why do you think there are so many tutorials written about how to put your subjects at ease, encourage them to be themselves, persuade them to unclench their teeth? Getting someone to sit where we tell them, do what we tell them, and yet “act naturally” involves a skill set that many photographers must learn over time, since they have to act as life-coach, father-confessor, camp counselor, and seducer, all at once. Also helps if you hand out lollipops.

Then again, shooting on the fly with the hope of capturing something essential about a person who is paying you zero attention is also fraught with risk, since you could crank off fifty frames and still go home without that person revealing anything real within the given time-frame. As with most issues photographic, there is no solution that works all of the time. I do find that one particular class of person affords you a slight edge in candid work, and that is performers. Catch a piece of them in the act of playing, singing, dancing, becoming, and you get as close to the heart of their essence that you, as an outsider, are ever going to get. If they are submerged in being, you might be lucky enough to witness something supernatural.

The more people lose themselves in a quest for the perfect sonata, the ultimate tap step, or the big money note, the less they are trying to give you a “version” of themselves, or worse yet, the rendition of themselves that they think plays well for the camera. As for you, candids work like any other kind of street photography. It’s on you to sense the moment as it arrives and grab it. It’s anything but easy, but better, when it works, then sitting someone amidst props and hoping they won’t freeze up on you.

There are two ways to catch magic in a box when it comes to portraits. One is to have a tremendous relationship with the person who is sitting for you, and the other is to be the best spy in the world when plucking an instant from a real life that is playing out in front of you. You have to know which tack to take, and where the best image can be extracted.

BREAKING THE BIG RULE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FACES ARE THE PRIMARY REASON THAT PHOTOGRAPHY FIRST “HAPPENED” FOR MOST OF US. Landscapes, the chronicling of history, the measurements of science, the abstract rearrangement of light, no other single subject impacts us on the same visceral level as the human countenance. Its celebrations and tragedies. Its discoveries and secrets. Its timeline of age.

It is in witnessing to faces that we first learn how photography works as an interpretive art. They provide us with the clearest stories, the most direct connection with our emotions and memories. And the standard way to do this is to show the entire face. Both eyes. Nose. Mouth. The works. Right?

But can’t we add both interpretation and a bit of mystery by showing less than a complete face? Would Mona Lisa be more or less intriguing if her eyes were absent from her famous portrait? Would her smile alone convey her mystic quality? Or are her eyes the sole irreplaceable element, and, if so, is her smile superfluous?

Instead of faces as mere remembrances of people, can’t we create something unique in the suggestion of people, of a faint ghost of their total presence” Can’t images convey something beyond a mere record of their features on a certain day and date? Something universal? Something timeless?

It seems that, as soon as we maintain rigidity on a rule….any rule…we are likewise putting a fence around how far we can see. The face is no more sacred than any other visual element we hope to shape.

Let’s not build a cage around it.

FRONT TO BACK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NOT ALL PORTRAITS INVOLVE FACES.

I’ll let that little bit of blasphemy sink in for a moment. After all, the face is supposed to be the key to a persona’s entire identity, and God knows that many a mediocre shot has been saved by a fascinating expression, right? The eyes are the window to the soul, and so on, and so forth, etc., etc.

But is this “face-centric” bias worthy of photographers, who are always re-writing the terms of visual engagement on every conceivable subject? Is there one single way to make a person register in an image? Obviously I don’t believe that, or else I wouldn’t have started this argument, but, beyond my native contrariness, I just am not content with there being a single, approved way of visualizing anything. I’ve seen too much amazing work done from every conceivable standpoint to admit of any limitation, or need for a “rule”, even when it comes to portraiture.

The face is many things, but it’s not the entire body, and even if you capture a shot in which the subject’s face is absent, he or she can be so very present in the feel of the picture. Arms, shoulders, the sinews, the stance, the way a body stands in a frame…all can bear testimony.

I recently stumbled onto an impromptu performance by a young string quartet, and faced the usual problem of not being able to simultaneously do justice to all four members’ faces, to balance the tension and concentration written on all their features in performance. In such situations, you have to make some kind of call: the picture becomes a dynamic tension between the shown and the hidden, just as the music is a push-and-pull between dominant and passive forces. You must decide what will remain unseen, and, sometimes, that’s a face.

As the music evolved, the two ladies seen above were, in different instants, either in charge of, or at the service of, the energy of the moment. For this picture, I saw more strength, more power in the back of the violinist than in the front of the cellist. It was body language, a kind of structural tug between the pair, and I voted for what I could not show fully. As it turned out, the violinist actually has a lovely face, one possessing a stern, disciplined intensity. On another day, her story would have been told very differently.

On this day, however, I was happy to have her turn her back on me.

And turn my own head around a bit.

SOFT EDGES, HARD TRUTHS

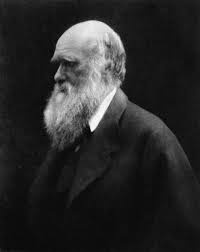

Charles Darwin sits for Julia Margaret Cameron. What she sacrificed in sharpness she gained in naturalness.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHATEVER MARVELS CURRENT TECHNOLOGY ALLOW US TO ACHIEVE IN PHOTOGRAPHY, there is one thing that it can never, ever afford us: the ability to be “present at the creation”, actively engaged at the dawn of an art in which nearly all of its practitioners are doing something fundamental for the very first time. The nineteenth century now shines forth as the most open, experimental and instinctive period within all of photography, peopled with pioneers who achieved things because there was no tradition to discourage them, mapping out the first roads that are now our well-worn highways. It is an amazing, matchless time of magic, risk, and invention.

Much of it was largely mechanical in nature, with the 1800’s marked by rapidly changing technical means for making images, for finding faster recording media and sharper lenses. The true thrill of early photography comes, however, from those who conjured ways of seeing and interpreting the world, rather than merely making a record of it. In some ways, creating a camera

Most 19th photographers could barely capture people as objects: Cameron transformed them into subjects.

facile enough to fix portraits on glass was easy. compared with the evolving philosophy of how to portray a person, what part of the subject to capture within the frame. And it was in this latter wizardry that Julia Margaret Cameron entered the pantheon of genuine genius.

Born to courtly British comfort in India in 1815, Cameron, largely a hobbyist, was one of the first photographers to move beyond the rigid, lifeless portraits of the era to generate works of investigation into the human spirit. She was technically bound by the same long exposures that made sitting for a picture such torture at the time, but, somehow, even though she endlessly posed, cajoled, and even bullied her subjects into position, she nonetheless achieved an intimacy in her work that the finest studio pros of the early 19th century could not approximate. Far from being put off by the softness that resulted from long exposures, Cameron embraced it, imbuing her shots with a gauzy, ethereal quality, a human look that made most other portraits look like staged lies.

In many cases, Julia Margaret Cameron’s eye has become the eye of history, since many who sat for her, like Charles Darwin, seldom or ever sat again for anyone else, making her view of their greatness the official view. And while she only practiced her craft for a scant fifteen years, no one who hopes to illuminate a personality in a photographic frame can be free of her heavenly mix of soft edges and hard truths.

Extra Credit: for more samples of JMC’s work, take this link to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cameron exhibition page:

http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2013/julia-margaret-cameron

THE “EITHER/ORs”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CAMERAS CAN EITHER TAKE CHOICE AWAY OR CHALLENGE YOU TO MASTER IT. If you’re a regular reader of this comic strip, you know all too well that I advocate making images with all manual settings rather than relying on automodes that can only come in a distant second to the human process of decision-making. People take better pictures with a camera than a camera can take alone. Can I get an Amen?

There is, of course, one choice you don’t get to make for any picture you create. You can’t mark a box called “the choice I made guarantees that everything in the image will work out.” Worse, there is always more than one choice being made in the creation of a photograph, and, even if you’re well-practiced and fast, you can’t make all of them perfectly. Choose one option and you are “un-choosing” another. The sum of the effect of all your choices together is what determines the final picture. That’s real work, and it certainly accounts for many people’s preference for automodes, since they obviate all those tough calls.

Nothing will force you to choose lots of options in short order like taking pictures of children at play. The image posted here, taken at a kindergarten playdate, shows a number of fast decisions that may or may not add up to an appealing picture, as lots of things are going on all at once. In the room where this was shot, space was tight, action was swift, white balances were wildly different in various zones within the room, and posing the kids in any way was absolutely impossible, due to their tender age and the fact that I wanted to be as invisible as possible, the better to catch their natural flow. To get pictures under this particular set of conditions, I had to decide how best to frame children who were grouping and ungrouping rapidly, where to get a fairly accurate register of color, customize my shutter speed and ISO with nearly every shot, and, as you see here, make my peace with whether the action implied in the shot outweighed the need for super sharpness.

You simply get into situations with some shots where you are not going to get everything you’d like to have, and you make decisions in the moment based on what each individual image seems to be “about”. Here I went for the joy, the bonding, the surging energy of the girls and let everything else take a back seat. Faced with the same situation seconds later, I might have remixed the elements to create a completely different result, but that is both the thrill and the bane of manual shooting. Automodes guarantee that you will get some kind of image, a very safe, if average, picture that allows you to worry less and possibly enjoy being in the moment to a greater degree….but you are the only factor than can take the photo to another level, to, in fact, take full responsibility for the result. It’s like the difference between taking a picture of Niagara Falls from your hotel room and taking it from a tightrope stretched across the raging waters.

And, ah, that difference is everything.

THE RELENTLESS MELT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE ARE PEOPLE YOU PHOTOGRAPH BECAUSE THEY ARE IMPORTANT. Others are chosen because they are elements in a composition. Or because they are interesting. Or horrific. Or dear in some way. Sometimes, however, you just have to photograph people because you like them, and what they represent about the human condition.

That was my simple, solid reaction upon seeing these two gentlemen engaged in conversation at a party. I like them. Their humanity reinforces and redeems mine.

This image is merely one of dozens I cranked out as I wandered through the guests at a recent reception for two of my very dearest friends. Given the distances many of us in the room traveled to be there, it’s unlikely I will ever see most of these people again, nor will I have the honor of knowing them in any other context except the convivial evening that herded us together for a time. Because I was largely eavesdropping on conversations between small groups of people who have known each other for a considerable time, I enjoyed the privilege often denied a photographer, the luxury of being invisible. No one was asked to pose or smile. No attempt was made to “mark the occasion” or make a record of any kind. And it proved to me, once more, that the best thing to relax a portrait subject is……another portrait subject.

I assume from the body language of these two men that they are friends, that is, that they weren’t just introduced on the spot by the hostess. There is history here. Shared somethings. I don’t need to know what specific links they have, or had. I just need to see the echoes of them on their faces. I had to frame and shoot them quickly, mostly to evade discovery, so in squeezing off several fast exposures I sacrificed a little softness, partly due to me, partly due to the animated nature of their conversation. It doesn’t bother me, nor does the little bit of noise suffered by shooting in a dim room at ISO 1000. I might have made a more technically perfect image if I’d had total control. Instead, I had a story in front of me and I wanted to possess it, so….

Susan Sontag, the social essayist whose final life partner was the photographer Annie Liebovitz, spoke wonderfully about the special theft, or what she called the “soft murder” of the photographic portrait when she noted that “to take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

Melt though it might, time also leaves a mark.

Caught in a box.

Treasured in the heart.

Related articles

- Susan Sontag Musings Where You Least Expect Them (hintmag.com)

THE WORLD IN A FACE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

The mystery isn’t in the technique. It’s in each of us.

THE AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHER HARRY CALLAHAN , author of the above quotation, knew about the subject of mystery, especially as it regarded women. Make that one woman, namely his wife Eleanor, who posed for Callahan’s camera for sixty-three years in every kind of setting from abstracts to nudes and back again, providing him with his most enduring muse.

Lucky man.

I know exactly how he felt. Because I feel the same way about my own wife, Marian.

Interpreting and re-interpreting a single face over time is one of the best ways I can imagine to train your eye to detect small changes, crucial evolutions in both your subject and your own sense of seeing. And Marian has given me that gift during our time together, as her features seem, to me, to be an inexhaustible source of exploration. It’s a face that is equal parts tenderness and iron resolve, a perfect balance between joy and tragedy, a wellspring of sensations. It is a great face, a great woman’s face, and a fascinating workspace.

Working as I always am to make her relax and forget herself when I am framing her up, I have long since abandoned the practice of announcing that I was going to take her photograph. There is never any posing or sitting. I approach her the way I would a stranger on the street. I wait for the moment when her face is in the act of becoming, than sneak off with whatever I can steal. Sometimes it takes a little more stealth than I am comfortable with, but my motives are simple; I don’t want the mechanics of photography to block what is coming from that face.

Phone conversations are my best friends, as they seem to magically suspend her self-consciousness and her awareness of the schmuck with the camera. And every once in a while, in viewing the results, she bestows my favorite compliment:

“That one’s not too bad…”

For praise like that, I’ll follow a face anywhere. Because the mystery isn’t in the technique.

It’s in all of her.

THE LIVING LAB

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GREATEST GIFT A SMALL CHILD HAS TO GIVE THE WORLD IS THE VAST, UNMINED ORE OF POSSIBILITY residing inside him. Wow, that really sounded pretentious. But think about it. He or she, as yet, has no wealth to offer, no fully developed talent, no seasoned insight, no marketable skills. It is what he or she has the potential to be that tantalizes us, and our cameras. It is what is just about to be available from these fresh, just-out-of-the-oven souls that amazes us, the degree to which they are not yet….us.

As a photographer, I find there is no better education than to be plunged into the living laboratory of cascading emotion that is a cluster of kids, and the more chaotic and unrehearsed the setting, the richer the results. It’s like shooting the wildest of competitive sports, where everything unfolds in an instant, for an instant. You ride a series of waves, all breaking into their final contours with completely different arcs and surges. There is no map, few guarantees, and just one rule: remain an outsider. The closer to invisibility you can get, the truer the final product.

I volunteer with an educational facility which designs many entry-level discovery workshops and playdates involving young families, requiring a lot of documentary photographs. What would be a chore or an extra duty for overworked administrative staff becomes an excuse, for me, to attend living labs of human experience, and I jump at the chance to walk silently around the edges of whatever adventure these kids are embarked on, whether a simple sing-a-long or a class in amateur dance.

Everything feeds me. It’s a learn-on-the-fly crash course in exposure, composition, often jarring variations in light, and the instantaneous nature of children. To be as non-disruptive as possible, I avoid flash and use a fast 35mm prime, which is a good solid portrait lens. It can’t zoom, however, so there is the extra challenge of getting close enough to the action without becoming a part of it, and in rooms where the lighting is iffy I may have to jack up ISO sensitivity pretty close to the edge of noise. Ideally, I don’t want the kids to be attending to me at all. They are there to react honestly to their friends, parents, and teachers, so there can be no posing, no “look over here, sweetie”, no “cheese”. What you lose in the total control of a formal studio you gain in rare glimpses into real, working minds.

The yields are low: while just anything I shoot can serve as a “document” for the facility’s purposes, for my own needs I am lucky to get one frame in a hundred that gives me something that works technically and emotionally. But for faces like these, I will gladly take those odds.

Who wouldn’t?

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

REDEMPTION, ONE FRAME AT A TIME

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS YOU READ THIS, I AM AVAILING MYSELF OF ONE OF THE MOST SPLENDID BENEFITS KNOWN TO A PHOTOGRAPHER: THE DO-OVER. Ahhh. Feels good just saying it. Do-over; the artistic equivalent of doing penance, of setting things right. Returning to the locales of your earlier misbegotten attempts at a subject, with just the chance that you’ve learned a few new tricks since your last try.

Redemption.

Maybe it’s just that possibility which thrills….that, and the hope of exorcising those little demons which jab you with pitchforks every time you look at shots from bygone outings. In my case, I’m trying to banish the Ghosts Of New Mexico Trips Past. It’s my third trip to the regions between Alberquerque and Abiquiu, which includes Santa Fe. It’s an odd mix of terrain, economic strata, art, superstition, spectacular vistas and harsh romance. Anything you want to shoot is there to be seen, some of it invisible and needing to be brought froth for the naked eye.

It’s not hard to see why painter Georgia O’Keeffe, banishing herself from the concrete canyons of Manhattan, decided to stage her own do-over in this mysterious land in 1929. O’Keefe had been a photographer’s wife, and painters and photogs are often twin kids of different mothers, so I emotionally understand what she saw in New Mexico, but far more than I have been able to intellectually convey.

So far.

It’s been nearly a decade from my first visit to my third, so I now have a little backlog of what will and won’t work, maybe even an inkling of what I’m trying to show going forward. I didn’t come back from the first two trips empty-handed, but I didn’t come back with the motherlode, either. Since the only real barriers to most photo do-overs are geographic, i.e., the means to return to the scene of the crime, I am really blessed at being able to get another at-bat at this incredible place.

Two strikes, three balls.

I plan to swing for the fences.

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

Related articles

- It seems to be my mission in life to wait on a dog (Georgia O’Keeffe) (upmostimpawtance.wordpress.com)

SCULPTING WITH SHADOWS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

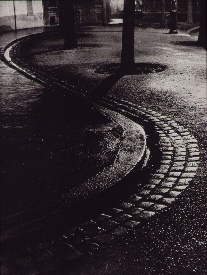

Brassai‘s world came to light at night.

ONE OF THE MIRACLES OF CONTEMPORARY PHOTOGRAPHY is how wonderfully oblivious we can afford to be to many of the mechanics of taking a picture. Whereas, in an earlier era, technical steps 1, 2, 3, 4 ,5, and 6 had to be completed before we could even hit the shutter button, we now routinely hop from “1” to “snap” with no thought of the process in between.

In short, we don’t have to sweat the small stuff, a truth that I was reminded of this week when imitating one of photographer’s earliest masters of night photography, Gyula Halasz, or “Brassai”, a nickname which refers to his hometown in Romania. Starting around 1924, Brassai visually made love to the streets of Paris after dark with the primitive cameras of the early 20th century, sculpting shape from shadow with a patiently laborious process of time exposures and creating ghostly, wonderful chronicles of a vanished world. He evolved over decades into one of the most strikingly romantic street artists of all time, and was one of the first photographers to have a show of his work mounted at New York’s MOMA.

Recently, the amazing photo website UTATA (www.utata.org), a workshop exchange for what it calls “tribal photography”, gave its visitors a chance to take their shot at an homage to half a dozen legendary visual stylists. The assignment asked Utata members to take images in the style of their favorite on the list, Brassai being mine.

In an age of limited lenses and horrifically slow films, Brassai’s exposure times were long and hard to calculate. One of his best tricks was lighting up a cigarette as he opened his lens, then timing the exposure by how long it took for the cig to burn down. He even used butts of different lengths and widths to vary his effect. Denizens of the city’s nightlife, walking through his long shots, often registered as ghosts or blurs, adding to the eerie result in photos of fogbound, rain-soaked cobblestone streets. I set out on my “homage” with a tripod in tow, ready to likewise go for a long exposure. Had my subject been less well-lit, I would have needed to do just that, but, as it turned out, a prime 35mm lens open to f/1.8 and set to an ISO of 500 allowed me to shoot handheld in 1/60 of a second, cranking off ten frames in a fraction of the time Brassai would have needed to make one. I felt grateful and guilty at the same time, until I realized that a purely technical advantage was all I had on the old wizard.

“Faux Brassai”, 2013. Far easier technically, far harder artistically. 1/60 sec., f/1.8, ISO 500, 35mm.

Brassai has shot so many of the iconic images that we have all inherited over the gulf of time that one small list from one small writer cannot contain half of them. I ask you instead to click the video link at the end of this post, and learn of, and from, this man.

Many technical land mines have been removed from our paths over photography’s lifetime, but the principal obstacle remains…the distance between head, hand, and heart. We still need to feel more than record, to interpret, more than just capture.

All other refinements are just tools toward that end.

THANKS TO OUR NEW FOLLOWERS! LOOK FOR THEM AT:

http://www.en.gravatar.com/icetlanture

http://www.en.gravatar.com/aperendu

Related articles

- Wonderful Photos of New York in 1957 by Brassaï (vintag.es)

GETTING BEYOND “SMILE”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE HUMAN RACE TAKES MORE PHOTOGRAPHS EVERY TWO MINUTES, TODAY, THAN WERE CAPTURED DURING THE ENTIRE 19th CENTURY. As staggering as that statistic is, it’s even more amazing on a personal level, when we contemplate how many of those gazillions of images involve our children, as we chase the ever-elusive goal of pictorially documenting (or so it seems) every second of their existence. Not only are we constantly on the job as shooters, our young ones must also be forever “on”, delivering camera-ready smiles and cherubic cuteness on cue.

With this in mind, it’s no wonder that kids actually evolve an alter ego to use for these “candid” moments after a while. Patented smiles, standby poses, a whole little system of default settings for quick use when Mom and Dad are in click mode. So, paradoxically, we are taking more and more pictures that reveal less and less about our children…..actually pushing their personalities further and further from discovery.

It’s tricky. And the results of our efforts actually count for more as time goes on, as traditional children’s portrait studios at department stores, malls, etc., are closing their doors. Increasingly, the pictures that we take of our kids are the ones which provide the most definitive chronicle of their most important years.

Point a camera at a child and he will try to give you what you want. But let him know it’s all right to inject himself into the process, and you will be amazed at the difference in the end product.

I recently took a series of informal portraits of several packs of Girl Scouts at a museum. They were told that they could use any of a variety of costume accents and musical instruments to create their own concept of the artists they saw on exhibit on their tour. Some of the girls organically assumed another identity completely, rock goddess, cowgirl, bluesy diva, and so on. Others stood frozen, as if waiting for me or someone “official” to tell them “what to do”. The hardest shots were the group portraits of the individual troops. The first frame was always stiff, awkward, like bankers at First National posing for a company picture in 1910.

However, simply by my saying just a few words like, “now act like you want to”, or, “now, act crazy”, the formal camera faces were stripped away, with truly great results. Arms on hips: attitude: dance poses: defiance.

Real kids.

I didn’t tell them what kind of pose to give me. I didn’t have to. They knew.

A camera can be a momentary intruder in a child’s busy day, but it doesn’t have to be. And photos of our children can actually show the magic behind the mechanical smile. However, the request that a kid show you something real must be a sincere one. And you have to be ready when the moment comes.

Getting beyond “smile” is the beginning of something wonderful.

(Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @mpnormaleye)

Related articles

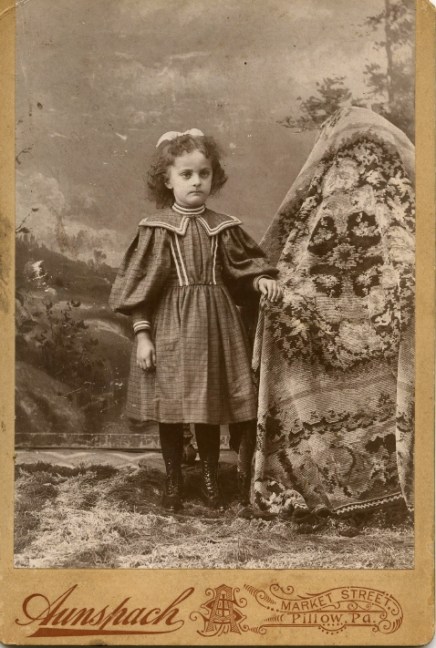

ESCAPE FROM PLANET PORTRAIT

Does this child look happy to you? Does she look like she even has a pulse? Surely we do better kid portraits today, er, don’t we?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

TO HEAR US TELL IT, WE ALL REALLY LOVE OUR KIDS. Assuming that to be true, why do we still subject them to the greatest act of photographic cruelty since Tod Browning’s Freaks? I speak of course, of the creatively bankrupt ritual of studio portraits, many of them cranked out at department stores or discount mills, too many of them making our beloved progeny look like waxworks escaped from a casting call for Beetlejuice.

We can surely do better.

I’m on record as believing that children are the noblest work of nature, coming into the world bearing only joy and untainted by the cynical clown olympics that comprise our “adult” way of thinking. And since we all probably feel the same way, why do so many of us park the little dears in front of hideous backdrops, surround them with absurd props, and gussy them up as everything from fairy princesses to ersatz puppies to fake cherubs?

Part of this ridiculous tradition owes its origins to the early days of photography, when a portrait sitting was the one means by which people who might never leave behind any other visual record of their lives were placed in formalized settings for an “official” rendering of their features. Slow film speeds and primitive lighting dictated that parents “leave it to the pros”, giving these modestly gifted artists decades of practice in weaving imaginary dream framings for our precious kids. (Full disclosure: Yes, I know that the image at left is a leftover from the Victorian age. I didn’t post any contemporary images because (a) many of them are almost this bad and you already get the idea, and (b) I wasn’t eager to be beaten to a pulp by any proud parents.)

Could it be more obvious, billions of Instamatics and Instagrams later, that this sad ritual hasn’t had any fresh air pumped into it since the golden age of Olan Mills class pictures? Even the most elementary “how-to” books on candid photography have been telling us the same thing for nearly a century: don’t formalize the setting, formalize your thinking. Let your child show you what he is, in his own environment. That means that you need to shoot constantly and invisibly, getting out of the kid’s way. No 3-2-1 “Cheese!” commands, no “sit up straight and don’t slouch” advice, no arbitrary situation.

Sure, you can basically plan how you will shoot your child, but allow him to unfold before your ready camera and gain the confidence to react in the moment. Stop trying to herd him into a structure or a setting. If at all possible, allow him to forget that you’re even in the room. Witness something wonderful instead of trying to construct it. Be a fly on the wall. The child is pitching great stuff every time he’s on the mound. Just make sure you’re behind the plate to to catch it.

Dirty little secret: there is nothing “magical” about most studio portraits. In fact, many of the results from the photo mills are just about the most un-magical pictures ever taken, although there are signs that things are changing. It simply isn’t enough to ensure a perfectly diffused background and an electronically exact flash. Even today’s most humble personal cameras have amazing flexibility to capture flattering light and isolate your subject from distracting backgrounds. And going from standard “kit” lenses (say, an 18-55mm) to an affordable prime lens (35mm, 50mm) gives us insane additional gobs of light to work with, all without using the dreaded pop-up flash, the photographic equivalent of child abuse.

Doing it yourself with kid portraits is work, make no mistake. You have to be flexible. You have to be fearless. And you have to know when something magical’s about to happen. But it’s your child, and there is no outside contractor who has a better sense of what delight he has inside him.

Besides, isn’t it likelier that he will show you the magic in his own back yard than in a back room at K-Mart? Give him something that he loves to do, the better to forget you’re there, and crank away. I mean shoot a lot. And don’t stop.

You’re the expert here.

Don’t outsource your joy.

THE ROOMS DOWN THE HALL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR THESE PAGES, IT WAS NEVER MY VISION TO MERELY POST PICTURES. Not, at least, without some kind of context. Just meeting a regular deadline with the “picture of the day” held as little interest for me as maintaining a diary, an oppressive regularity that I have resisted my entire life. For the most part, the images on THE NORMAL EYE are here to anchor my thoughts about what it feels like to be enticed, seduced, enthralled, and, yes, disappointed by photography, to caption the frames with some semblance of the creative process, at least as I had the poor power to see it at the time.Like all blogs, it is written on my own very personal terms. I am always thrilled to harvest reaction and comment, since, as Ike Turner once sang, “was my plan from the very began”. But the important thing is to get the thoughts right, or at least to use them as a guide to the shots. Thus, the mission is neither words nor pictures, but some kind of handshake symbiosis between the two.

FOR THESE PAGES, IT WAS NEVER MY VISION TO MERELY POST PICTURES. Not, at least, without some kind of context. Just meeting a regular deadline with the “picture of the day” held as little interest for me as maintaining a diary, an oppressive regularity that I have resisted my entire life. For the most part, the images on THE NORMAL EYE are here to anchor my thoughts about what it feels like to be enticed, seduced, enthralled, and, yes, disappointed by photography, to caption the frames with some semblance of the creative process, at least as I had the poor power to see it at the time.Like all blogs, it is written on my own very personal terms. I am always thrilled to harvest reaction and comment, since, as Ike Turner once sang, “was my plan from the very began”. But the important thing is to get the thoughts right, or at least to use them as a guide to the shots. Thus, the mission is neither words nor pictures, but some kind of handshake symbiosis between the two.

However, since day one, I have reserved several gallery pages on which visual info is pretty much all there is, since I also believe that it is important to react to photographs on a purely visceral basis. If the blog is the main hall in the house, think of these as the rooms down the hall that you never thought to explore.

I have tried to give each gallery its own general feel, since there are different “themes” which motivate our taking of pictures, and I thought, for this post, it might be helpful to underscore those themes just enough to justify how they were organized. I have now also given them specific names instead of the A-B-C tags they had previously.

Here’s the new rundown:

Gallery A is now “HDR”, since I think that this process affords very specific benefits for reproducing the entire range of visible light in a way that, until recently, has been impracticable for many shooters. No tool is suitable for every kind of shooting situation, but HDR comes close to reproducing what the eye sees, and can enhance detail in fascinating ways. There is a lot controversy over its best use, so, like everywhere else on this blog, your opinions are invited.

The former B gallery is a collection of impulse shots. All of these images were taken in the moment, on a whim, with only instinct to guide me. No real formal prep went into the making of any of them, as they were the product of those instants when something just feels right, and you try to snag it before it vanishes. We’ll call these “SNAP JUDGEMENTS”.

And finally, the photos formerly known as Gallery “C” are now renamed “NATURAL STATE”, as these portraits are all shot using available light, captured without flash or the manipulation of light through reflectors, umbrellas, or other tools.

Let me state here that your participation in this forum was always the centerpiece of my doing it in the first place, and your ideas and suggestions have always inspired me to try to be worthy of the space I’m taking up. I also have enjoyed linking back to your individual sites and visions. It’s a great way to learn.

ideas and suggestions have always inspired me to try to be worthy of the space I’m taking up. I also have enjoyed linking back to your individual sites and visions. It’s a great way to learn.

So please know that, when you click the “like” button at the bottom of these posts, or take the time to type a comment, it does help me see what works, as well as what needs to be done better. I don’t believe that art can grow in a vacuum, and I thank everyone for giving these pages shape and form.

And thanks for exploring all the rooms in my house.

FLATTERY WILL GET YOU NOWHERE

My beautiful mother, well past 21 but curator of a remarkable face. Window light softens, but does not erase, the textures of her features. 1/60 sec., f/4.5, ISO 200. 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE DEPICTION OF THE FACES OF THOSE WE LOVE IS AMONG THE MOST DIVISIVE QUESTIONS IN PHOTOGRAPHY. Since the beginning of the medium, thoughts on how to capture them “best” clearly fall into two opposing camps. In one corner, the feeling that we must idealize, glamorize, venerate the features of those most special in our lives. In the other corner, the belief that we should capture faces as effects of time and space, that is, record them, without seeking to impose standards of grace or beauty on what is in front of the lens. This leads us to see faces as objects among other objects.

The first, more cosmetic view of faces, which calls for ideal lighting, a flattering composition, a little “sweetening” in the taking, will always be the more popular view, and its resultant images will always be cherished for emotionally legitimate reasons. The second view is, let’s “face” it, a hard sell. You have to be ready for a set series of responses from your subjects, usually including:

Don’t take me. I just got up.

God, I look so old. Delete that.

I hate having my picture taken.

That doesn’t even look like me.

Of course, since no one is truly aware of what they “look like”, there is always an element of terror in having a “no frills” portrait taken. God help me, maybe I really do look like that. And most of us don’t want to push to get through people’s defenses. It’s uncomfortable. It’s awkward. And, in this photo-saturated world, it’s a major trick to get people to drop their instinctive masks, even if they want to.

Still.

As I visually measure the advance of age on my living parents (both 80+ ) and have enough etchings on my own features to mirror theirs, I am keener than ever to avoid limiting my images of us all to mere prettiness. I am particularly inspired by photographers who actually entered into a kind of understanding with their closest life partners to make a sort of document out of time’s effects. Two extreme examples: Richard Avedon’s father and Annie Leibovitz’ partner Susan Sontag were both documented in their losing battles with age and disease as willing participants in a very special relationship with very special photographers….arrangements which certainly are out of the question for many of us. And yet, there is so much to be gained by making a testament of sorts out of even simple snaps. This was an important face in my life, the image can say, and here is how it looked, having survived more than 3/4 of a century. Such portraits are not to be considered “right” or “wrong” against more conventional pictures, but they should be at least a part of the way we mark human lives.

Everyone has to decide their own comfort zone, and how far it can be extended. But I think we have to stretch a bit. Pictures of essentially beautiful people who, at the moment the shutter snaps, haven’t done up their hair, put on their makeup, or conveniently lost forty pounds. People in less than perfect light, but with features which have eloquent statements and truths writ large in their every line and crevice. We should also practice on ourselves, since our faces are important to other people, and ours, like theirs, are going to go away someday.

In trying to record these statements and truths, mere flattery will get us nowhere. The camera has an eye to see; let’s take off the rose-colored filter, at least for a few frames.

Related articles

- The Great Richard Avedon (sandroesposito.wordpress.com)