THE PHANTOM MENACE

Eagles with the jitters: jagged lines and poor definition from “heat shimmer”.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CATCHING THE PERFECT GLIMPSE OF A SKYSCRAPER is more luck than craft, and, in a city like New York (okay, there is no city like New York), you have a million different vantage points from which to view a sliver or slice of buildings that are too generally immense to be captured in their entirety. You pick your time and your battle.

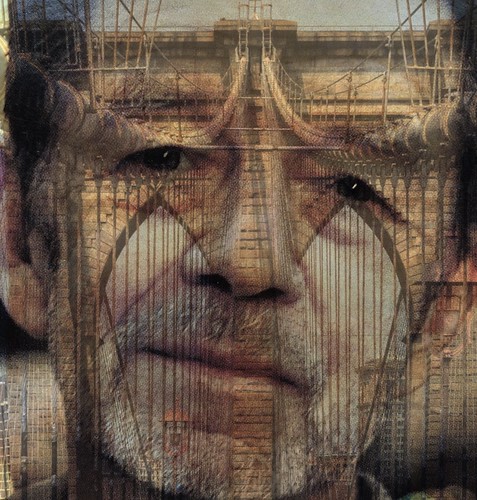

One of the short cuts to the perfect view of these titans is, of course, a telephoto lens. I mean, what could be easier? Zoom, focus, shoot. Except that, with very long lenses, even the most sophisticated ones, things happen to light that are very different from how illumination works at close quarters. One problem for zoomers is the dreaded “heat shimmer”, the thermal layers that occur in between camera and far-away subject, warping straight lines and turning fine detail into mush. Sharpness in zoom shots can suffer because heat waves, which can vary widely depending on prevailing weather conditions, are bending the light and confusing your camera’s auto-focus system. The tight shot of the eagle gargoyles at the 61st floor of the Chrysler building, seen up top here, is a good example. They resemble a charcoal sketch more than they do a photograph. This image was shot from about a 1/4 mile away on the banks of an inlet bay near Greenpoint, Brooklyn, looking across at the Manhattan skyline. It was taken on a Nikon Coolpix P900, one of the brand’s so-called “superzooms”, allowing me to crank out to about 2000mm.

Still an imperfect shot, but snapped at the same focal length with somewhat straighter results. Wha?

And yet, consider the other shot, also of the upper floors of the Chrysler, and also shot at 2000mm just minutes away from the gargoyle image. Lines are generally solid and straight, even though shot from just about the same distance. Here’s where we get to the key word “variable”. Everything I shot in this batch was in the early morning, and so the sun was actively burning off a light overcast, which, I assume, made for shifting air temperatures in nearly everything I photographed. The P900’s small sensor, which is what happens when your put too many glass elements in a compact lens, pretty much shoots contrast to hell at long distances, as you can see in both shots, and responds to anything other than direct light with zooms that are, to be kind, soft. Still, being mindful of heat shimmer as a real factor in your telephoto work can sometimes result in pictures that, while far from perfect, are technically acceptable. The phantom menace can’t be eradicated, but it can be tamed.

AT THE CORNER OF “WHAT THE” & “WHERE THE”

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHS ARE AS MUCH ABOUT CONDITIONS AS OBJECTS. The first grand age of picture-making was chiefly about documenting the physical world, recording its everyday features like waterfalls, mountains, pyramids, cathedrals. The earliest photographs were, in that way, mostly collections of things. Next came the birth of photographic interpretation, in which we tried to record what something might feel like as well as what it looked like. Conditions. Sensations. Impressions.

One thing that will invariably send me grabbing for a camera is when two seemingly disparate things create a unique relationship just by been juxtaposed with each other, as in the image you see here. The cheek-by-jowl relationship between the imposed order of Manhattan and the sacrosanct green space of Central Park has always been, to me, the ultimate study in contrasts. Acres of trees, lawns, playing fields, lakes, rolling hills, footbridges, and walking paths surrounded by a yawning, jutting canyon of steel and stone; the logic of the engineer yielding to the dreamy randomness of Nature.

The crags seen here just yards away from the skyscrapers of Central Park West look less like rock formations than the debris left after a war, as if the towers just beyond were somehow spared from an aerial bombardment. The contrast between order and chaos (and our shifting definitions of both of those terms) could hardly be sharper; so stark that, after shooting several frames of the scene in color, I decided that monochrome might better sell the entire idea of selective destruction, almost like unearthing an archived newsreel. The man on the upper left edge of the frame and the one standing alone in the gap between the rocks and the buildings both, to me, resemble the morning-after teams that might tour the damage a the previous night’s raid, salvaging what they can from the wreckage. Thus do photographs of things become documents of conditions, of the intersection between “what the” and “where the”. It’s a strange, and occasionally wondrous, juncture in which to find oneself.

New year-end galleries! Click on the tabs at the top of the page for new 2024 image collections.

INVISIBLE MIRACLES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

WHEN YOU’RE A CITY THAT HOSTS OVER EIGHT MILLION PEOPLE, certain things, even certain extraordinary things, are bound to get lost in the shuffle. In fact, maybe “shuffle” is the perfect word for what happens to people in a town like New York; they become part of an endless mixing of cards, from Joker to Knave, King to commoner, in an equally endless jumble of encounters. Maybe the lyric “if I can make it there” is more correctly worded “if I can get noticed there”. The sheer speed of the shuffle guarantees that the daily menu of things contains many unseen tragedies, many invisible miracles.

The city is so very crammed with every aspect of the human experiment that it is, by definition, jam-packed with extraordinary talents, great feats. There is, on any given day, an embarrassment of artistic riches that just passes unseen. In other places, the marvelous is more of a rarity. In New York, it’s the very mortar between the bricks. Where else but in New York could a vast greenspace like Central Park be merely part of the local scene, as if it were an old lady’s backyard garden? And where else but in Central Park could a superb saxophonist, like the one seen here, merely be the latest amazing musician you encountered on your morning stroll, halfway between the a capella quartet near the children’s zoo and the gypsy accordionist next to the Bethesda fountain?

The most New York thing about this player’s performance, however, is the degree to which he is being regarded not as an extraordinary musician, but as just another element in the daily mix of sensations. As a frequent visitor that is not a native, my first instinct is still to point a camera at this gentleman, because of course he must be acknowledged, and of course people should struggle to be aware of him. But in Manhattan, there is always the next sensation, the next show, just as, if you miss the latest 7 train, there will be another one just as good arriving in the next few minutes.

Maybe if I were ever to become an actual NYC resident, I would eventually get to the point where more of the city’s on-tap miracles would become invisible to me, so commonplace as not to even merit a camera click. But a regular willingness to be surprised, even amazed, is at the heart of every photographer I have every admired, and, so far, it’s an instinct that has served me well. Maybe I’m just not very sophisticated, living up to the Ohio farmboy rep many have hung on me, the little frog awash in the big pond, and so on.

Maybe I am, indeed, every inch a hayseed. A cornball. A bug-eyed kid agog on his first visit to the circus.

Cool.

I can live with that.

AND IT WAS ALL YELLOW….

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE LATE COLUMNIST PETE HAMILL ONCE DEFINED A “REAL” NEW YORKER as one who could tell you, in great detail, what a great town New York used to be. I was born in Ohio, but, as I married a woman who grew up in the city and its immediate environs, I have been privileged to visit there scads of times over the past twenty years, enough that I have been able to compile my own personal list of longings for Things That Have Gone Away in the Apple. There are the usual pangs for beloved bars and restaurants; bittersweet memories of buildings that fell to the unfeeling juggernaut of Progress; and the more abstract list of things that could be called How We Used To Do Things Around Here.

For me, one of those vanishing signposts of all things Noo Yawk is the great American taxi.

Take Me Uptown, October 12, 2024

As the gig economy has more or less neutered the cab industry in most cities, the ubiquitous river of yellow Checkers that used to flood every major NYC street at all turns is now a trickle, as Uber and Lyft drivers work in their own personal vehicles, causing one of the major visual signatures of life in the city to ebb, like a gradually disintegrating phantom. As much as the subway or sidewalk hot dog wagons, cabs are a cue to the eye, perhaps even the heart, that a distinct thing called “New York” endures. As a photographer, I’ve caught many huge flocks of them careening down the avenue over the years, even on days when I couldn’t, for the life of me, get even one to stop for me. Now, on a recent trip that was my first time in New York in nearly five years, spotting even one Checker was something of an event for me, and suddenly posed a bit of a photographic challenge.

The problem with taxis, now, is to show not only the physical object itself, but to visually suggest that it is slowly going ghost, fading into extinction. In such situations, I find myself with the always-tricky test of trying to photograph a feeling, finding that mere reality is, somehow, inadequate to the task. It bears stating that I am, typically, a straight-out-of-the-camera guy; I make my best effort to say everything I have to say before I click the shutter. That’s neither right nor wrong; it’s just the way I roll. And so, for me to lean heavily on post-tweak processing, I have to really be after something specific that I believe is outside of the power of the camera itself. The above shot, leaning heavily on such dream-feel, is even more ironic, because the Checker in question is no longer a working unit, but a prop parked permanently in front of a funky-chic boutique hotel. In other words, a museum piece. A relic.

Like moi.

Pete Hamill knew that New York’s only perpetual export is change. Managing that change means managing ourselves; knowing what to say hello and goodbye to; and hoping that we guess right most of the time on what’s worth keeping. Or maybe, just to forever hear a New York cabbie shouting over his shoulder to us, “Where To, Mac?”

REDEMPTION, ARRIVING ON TRACK 11

In the old time, you arrived at Pennsylvania Station at the train platform. You went up the stairs to heaven. Make that Manhattan. And we shall have it again. Praise All.

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan

Main concourse, Moynihan Train Hall, New York City

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR THOSE WHO LIVE OUTSIDE NEW YORK CITY, it is hard to express the sense of loss that’s is still felt locally over the 1963 demolition of the old Penn Station railroad terminal. Crumbling from age and neglect, it was one of hundreds of landmarks that fell to the wrecking ball in an age where so-called “urban renewal” reigned supreme, and its end has continued to haunt urban planners ever since, as the very definition of a wasted opportunity. Today, classic buildings are more typically salvaged and repurposed, allowing their storied legacies to write new chapters for succeeding generations. Penn Station’s death was the Original Sin of a more careless age.

But sins can sometimes be redeemed.

“The Hive” , a dramatic art installation inside the 21st Street entrance to Moynihan Train Hall.

Around 2000, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who, years before, had worked as a shoeshine boy inside the first Penn Station (which was “replaced” by a grim dungeon in the ’60’s on its original site), began to float the idea of augmenting rail access to Amtrak and other carriers by recreating the majesty of the old building in the most obvious place; across the street. Turns out that the terminal had a near-twin, just beyond the crosswalk on Eighth Avenue in New York’s old main post office, which, like the train station, was designed by the legendary firm of McKim, Mead & White. By the start of the 21st century, the post office, by then known as the James Farley building, had already begun to move many of its operations to other facilities, heading for white elephant status in one of the city’s most expensive neighborhoods. By the senator’s death in 2003, funding for what many locals were already calling the Moynihan Train Hall went through years of fiscal stop-and-start, careening like a foster child through the hands of half a dozen different potential sponsors. Construction finally began in 2017, with special care taken to preserve and restore the post office’s massive colonnade entrance, which was, itself, protected with landmark status.

On January 1, 2021, almost as a symbol of New York’s resurrection following its year-long struggle as the first epicenter of the Covid pandemic, the completed Moynihan Train Hall was finally dedicated by New York governor Andrew Cuomo. My photographs of the site now join those of millions of others as testimony to the power of the human imagination, as do the Hall’s waiting-room murals, which illustrate the grandeur of the terminal’s long-vanished predecessor, poignant reminders of the new building’s purpose in redeeming the sin of letting the old one be lost. Among the mural captions are the words of Daniel Patrick Moynihan himself, celebrating the town’s unique trove of tradition and talent:

Where else but in New York could you tear down a beautiful beaux-arts building and find another one across the street?

Amen. Praise all.

THE VERY PICTURE OF….ANOTHER PICTURE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

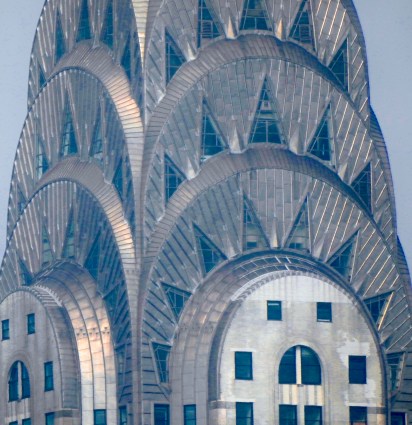

I CAN’T BE THE ONLY PERSON WHO HAS EVER SEEN this classic image of photographer Margaret Bourke-White peering over a stainless-steel projection near the top of the Chrysler Building and asked themself, “so who in heck is taking this picture?”

Oh sure, we know the basics of the story. In 1930, The skyscraper’s owners invited the already-renowned MBW to set up her wooden view camera on one of the structure’s eight gleaming eagle’s heads at the 61st floor, and take in what was then an extremely privileged view of Manhattan. The building, not yet quite completed, would eventually top out at 1,046 feet (77 stories) above the pavement, winning one of the city’s most celebrated “skyscraper wars”, cinching its right to Tallest stature by virtue of the gigantic steel spire that served as its crown. Bourke-White, whose studio was then located in Cleveland, had already considered moving to NYC to be nearer her employers at Fortune magazine, and once she ascended to take in the, er, eagle’s-eye view, she decided that the Chrysler itself should be her new HQ, all the better for her to be the two eagles on the corner where she shot, which she nicknamed “Min” and “Bill” after a popular movie of the time.

But who else made the ascent that day, to take a picture of her.. taking a picture?

Introducing the nearly-forgotten Oscar Graubner, Margaret’s full-time darkroom assistant and amateur snapper, who often traveled with Bourke-White on what was, by the early ’30’s, already a global trajectory, a career which would take her from the opening of hydroelectric dams (the first Life magazine cover ever) to photo-essays in the young Soviet Union to, eventually, every major theatre in the European war and the India-Pakistan schism. Graubner was part of what built MBW’s nickname of “Maggie The Indestructible”, and, by chance, snapped the best image of her at work. Strangely, his picture of her doing her thing from the top of the Chrysler has now been viewed many millions of times more than any pictures she actually made herself from up there. The history of photography may be peopled by giants, but it’s punctuated by those who toil in their immense shadows.

OLD AND NEW AND STRANGE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS BOTH A DESTROYER AND RE-SHAPER OF CONTEXT. Destroyer, since, by freezing isolated moments, it tears things free of their original surrounding reality, like lifting the Empire State out of Manhattan and setting it afloat in the upper atmosphere. Re-shaper, since it can take the same iconic building and, merely by shooting it from a different angle or in a different light or on a different street, make it seem novel, as if we are seeing it for the first time. That odd mix of old and new and strange are forever wrestling with each other depending on who wields the camera, and it’s one of the qualities that keeps photography perpetually fresh for me.

Take our famous Lady Liberty. It is burned into the global consciousness as one of the most powerful symbols on the planet, and its strength derives in part from the more-or-less “official” way it is photographed. We see it towering above the harbor, mostly from the front or side. Most of our snaps of it are destined to be echoes and recreations of mostly the same way of seeing it that has been chosen by the millions that have gone before us. Its context seems locked in for all time, and that frozen status strikes many of us as “proper” or “appropriate”.

But what does the same object look like if we force ourselves to go beyond the official view? Seen from the back, for example, as seen here, can it be upstaged, or at least redefined, by a refreshment stand or the golden colors of autumn? Do we even think of the statue as being in front of or to the side of or behind or framed by anything? Of course, what you see here is not a majestic picture, as may be the case in the standard “postcard” framing. But can that be valuable, to reduce the icon to merely another object in the frame? Can anything be learned by knocking the lady off her lofty perch, separate from all accepted versions?

Thing is, as we stated up top, that re-ordering of our visual concept of something is a key function of the making of pictures. We not only shoot what is, but what else may be. I’ve spoken with New Yorkers whose daily commute placed the Statue right outside their car window every morning of their working life, eventually rendering it as non-miraculous as a garbage truck or a billboard. For them, would a different version of the figure be revelatory? Making pictures is at least partly about approaching something stored by everyone in the “seen it” category, and saying, “wait….wait…not so fast…..”

SHOULD AULD ACQUAINTANCE BE FORGOT…

An experimental mix of pedestrian and auto space shows Times Square in transition, 2009.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AS I WRITE THIS, in about the eleventh hour of the new year 2023, cleaning crews are still restoring Times Square to its regular state of controlled chaos, a steady rhythm of wretched excess that, every December 31st, erupts into an even more intense blizzard of litter and license, a national ritual marking the shift from one year to another. And along with the tons of confetti and collapsed Planet Fitness top hats that will be swept away, the square itself, like an endlessly re-sculpted shoreline, settles back into a shape that is totally the same and yet totally different.

It’s hard to believe that ’23 will only mark the ninth year since the conversion of the world’s most famous address to 100% pedestrian traffic. What began in 2009 as a partial experiment in accident control (following a tsunami of auto mishaps in the neighborhood) proved so popular that, by 2014, a permanent change was effected, making Times Square a total walking district/would-be park, or “public space” as we now call it. During the transition, native New Yawkers griped about the Square’s total surrender to the dreaded onslaught of tourists, and the area’s main architectural feature became five-story, perpetually-blazing billboards for Broadway shows, chain restaurants and soft drinks. Nearly a decade later, the jury’s still out on whether the changes produced a bright, cheery playland or a grotesque Sodom. The answer you get depends on who you ask.

Just two years later, in 2011, the Square has been completely converted to 100% foot traffic. How Times (Square) change(s).

The take-away for photographers is that if, on any given day, you see a version of the Square that you like, preserve it, as I did in the above from a Sunday morning in November of 2011. Like all other images before it, this particular “Times Square” is now a frozen abstraction of a place that is just the same, only different. And it was ever thus: going back nearly a century to when the “new” Times building opened to literal explosions of dynamite to mark the incoming year, the neighborhood has served as a mercurial barometer of America’s quick, impatient transit. Perhaps it was the crossroads effect, the coming together of so many disparate motives, all colliding near the nexus of the popular press, show business, and loud, insistent commerce. Perhaps it is our worhip of the novel, the new. For whatever reason, the Square evolved from day-to-day like the subtle oscillations of a seismograph, taking a measure of the country’s cultural plates and how they scrape and grind against each other in the city’s inexorable tectonic ballet.

We all understand the concept that only change is permanent. After all, even the New York Times only occupied offices at “One Times Square” for eight years. Still, there are few places on Earth where that impermanence is evidenced in such undeniably visual detail. Life in New York at large is all, to a degree, arranged around the dictum of Do It Now. But in Times Square, the frames of film flicker by so very quickly that individual images, no longer distinguishable, rush into a blurry illusion of continuous motion….the ultimate movie. Small wonder that we treasure a few frozen frames as the parade crushes past us.

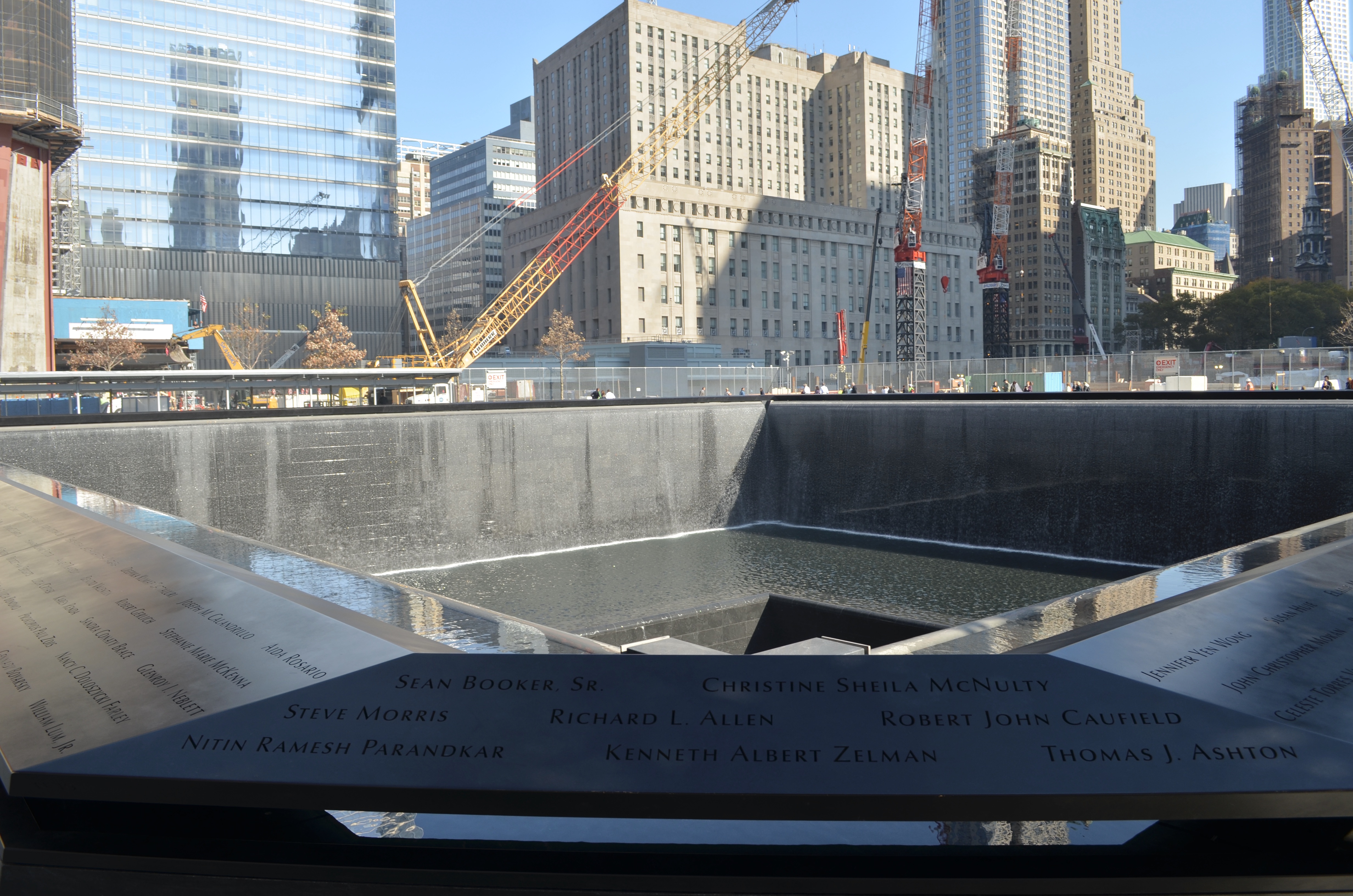

THE RISING, COMPLETED

By MICHAEL PERKINS

September 11, 2022

TWENTY-ONE YEARS. The life of a legally arrived adult. The space of a generation. How much time has passed since the horror of 9/11, and yet how immediate remains its emotional resonance. Photographers the world over, then and now, have tried to capture the surreal universal gasp of shock that unfurled in those few minutes on 9/11/01. And now, today, as the wound has become the scar and the flash has morphed into a flashback, an entirely reborn Lower Manhattan both recalls the history and serves, ironically, to obliterate it. For those who make images, the present era is a fraught one.

The first pictures, of course, were of the burning, the dying, the national open grave. The second wave of images was of the remains of people and buildings being literally trucked away, of a starched, scraped plain that promised a a repurposing. Coming soon on this site. Flags and markers and makeshift memorials, as holy as they were to many, were soon ushered offstage, as New York, the city that knows more about staging revivals than any other, prepared for a new production. As a frequent visitor to New York over the past fifteen years, I was present at many of the stages of the set design.

Lights, action, rebirth.

I have tried to have it both ways with the pictures I have made in the area, with both respectful homages to the sacramentals within the September 11th museum and the memorial pools, and the explosion of creative energy that mushroomed into the new WTC plaza. It’s been a high-wire act, artistically and emotionally, but I feel an urge now, to move my lens almost exclusively to The Next Act, since it now exists not merely as a yearning for a return to normalcy, but as a defiant fait d’accompli, another proof that New Yorkers are always about Getting On With It.

This image, with its lettered reflection of the 90 Church Street Post Office (which was itself littered with falling debris of the twin towers’ collapse), is my attempt to capture past survivors and forward strivers in the same frame, to say, yes, amen, a prayer for the dying, but also yes, hell yes, for the indomitability of America, which honors its founders best when doubters prematurely pronounce it out for the count.

We are back.

We are always back.

We are staying.

POP GOES THE CONTRAST

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NIGHT CITYSCAPES PRESENT TREMENDOUS OPPORTUNITIES to me these days, especially with the technical advances of recent years. Many shots that required tripods or lengthy exposures just a short while ago are now possible as handheld snaps. Great improvements in the balanced exposure performance and color rendering of digital sensors, along with smoother resolution, even at higher ISO settings, have tamed the “black ‘n’ blurry” curse of night images that haunted much of my earlier work. Even so, I still employ a few old-school tricks to further improve my odds, as I try to impart a greater sense of depth, or “space” in pictures jammed with competing information.

Glasscade, 2019

Conveying a dimensional look in the dense mashup of buildings of a big city can be tricky. I could certainly decide to avoid the problem completely, deliberately going for a flatter effect with the use of a zoom lens (a look I don’t really like). If, however, I do want parts of the photograph to “pop” in reference to others, there are a few things to try. Shooting foregrounds and backgrounds with boldly divergent color schemes and textures, as I was able to do in this image, can help the various layers of the image to stand out in clear relief from each other. Experimenting with depth of field can also diminish the focus of one plane and make the other call more loudly for the eye’s attention. Additionally, foreground objects (like the immense billboard at left) can be partially cropped out (as seen here) so that they only narrowly enter the edges of the shot, operating as a kind of partial frame around the main subject.

Shooting on the fly in night cityscapes can still be tricky for me. Take bright downtowns areas, like, say the bright-as-eff, blitzkrieg of light in Time Square, which falls off to nearly nothing within the space of a single city block because distant structures are used less at night, creating a contrast nightmare. Newer cameras are better at capturing detail in the shadows, or at least enough of it to be retrieved in post-production, but the real challenge is taking the time to plan a shot when (a) technology frequently rewards us for even an imperfectly executed image and (b) the overall stimulus level of the city tends to make us shoot more and shoot faster, rather than slowly and purposefully. As always, your best shots are balanced on a knife’s-edge between impulse and deliberation.

THE INEXHAUSTIBLES

By MICHAEL PERKINS

“A ROSE IS A ROSE IS A ROSE“, wrote Gertrude Stein, asserting that a thing is merely itself, and nothing else. It’s a classic quote, but a sentiment which is belied by any kind of interpretative art. For the painter, the poet, the photographer, or the sculpturer, the physical limits of an object are merely the jumping-off point to one’s personal way of depicting or describing. Certainly, in one sense, a rose is “merely” a rose. However, in the hands of an artist, it is always, potentially, on its way to being everything else.

Photographers instinctively know that they are not mere recorders of “reality”, that, in their hands, subjects are exaggerated, emphasized, abstracted. We make images of roses, certainly, but also the rose-pluses, the rose-minuses, the rose absurd, the rose imagined. This ability to tailor the showing of things to our ever-evolving sense of their meaning to us allows us to approach even the most over-documented things with fresh eyes.

It may be that nearly everyone with a camera who’s walked the streets of Paris has, somewhere in their portfolio, a shot of the Eiffel tower. In some ways, the challenge of trying to say anything new about what we might consider an “exhausted” subject is irresistible: we sort of dare ourselves to do a fresh take on it. The thing is, our depiction of these celebrated places, once we have trained our eyes, is actually unbound, or inexhaustible. It is only how well we have developed the muscles of our imagination that determines how many gazillions of personal Eiffels can exist.

The image here of a small selected vista from within the sixteen-story layout (2500 steps, 154 flights of stairs, 80 separate landings) of New York City’s Vessel shows, if nothing else, that there can never truly be a “typical” view of the structure. The visual story changes every few feet or so, depending on where you are standing, and even multiple frames taken from the same vantage point just minutes apart from each other will yield vastly different results, since light, color and the arrangement of visitors is not static. This is great news for anyone who might doubt that they could make a personal picture of something so overwhelmingly public or famous. My point is that you can’t not produce something personal of it, because, for photographic purposes, not only this object, but nearly everything, is inexhaustible.

It’s not that the many millions of images taken of a famous place over time may not seem remarkably consistent, in that they almost replicate each other. It’s that such a result is not predestined, any more than any other photograph we attempt is. Change something in the eye of the beholder, and you may discover that even the eternal rose is, well, something other than a rose. Sometimes.

OPENING DAYS / CLOSING NIGHTS

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S NOT HYPERBOLE TO SAY THAT THE GREAT HIBERNATION, our global banishment from our regular lives, feels a bit like living through a war. As in a traditional conflict, there are separations, sudden deaths, deprivations, and a feeling of “where have I been?” that accompanies our every venture outside our safe zones. So many of us have simply backed out of the flow of time that, as in times of war, we are startled by what has been altered or even vanished since the last time we cautiously emerged to explore the sites of our old existence. And that shock, in turn, informs all of our art, including, of course, photography.

The first thing that we notice is that so many things that were solid and substantial before we ducked under cover have been either greatly altered or completely vaporized. And the sensation is not limited to things that were already crumbling, but also includes things that were just becoming part of our world in the moments immediately before the lockdown. Places that just cut their ribbons of newness a heartbeat ago, but which already find themselves neutralized, obsolete. Of course, society is always closing chapters and tearing down buildings, in a cycle of goodbyes that seem almost normal, pandemic or no. But the toll created by our withdrawal from the daily parade also lists things that were just getting started, the space between their grand opening days and dark closing nights shrunk by circumstance . And our photographs of those things, taken either before or after these brief appearances, are poignant images of what might have been, a measure of the gap between our hopes and the ruthless randomness of this strange new world.

The now-vacant “Vessel” stands opposite Hudson Yards’ Public Square in the long-ago Manhattan of 2019.

As one example, consider this image of Vessel, a bold (and controversial) open-air attraction that acts as a kind of visual rendezvous at the head of the massive new Hudson Yards district in Manhattan. Part sculpture, part observation deck, part tourist trap, the structure sits opposite the main entry to the Yards’ Public Square mall. Built at a cost of 200 million dollars, it rose to sixteen floors, honeycombed 154 flights of stairs, and became an instant hit with visitors, who were admitted via free but timed tickets. Vessel’s very bigness rendered its actual value as art moot; like the Eiffel Tower (to which it was compared) or Niagara Falls, it just was, and, in so being, became part of what you do when you “do” New York. It opened to the public in March of 2019.

You can guess a lot of what followed. As NYC locked down, retail took a major hit and retail on the massively ostentatious scale seen at Hudson Yards took an even bigger one. Leases were renegotiated, then abandoned outright. The project (still unfinished) that was designed to reconfigure an entire economic sector of the Apple was down on one knee. And something weirdly symptomatic of the times occurred with Vessel; people started to jump off of it to their deaths. Last month (January 2021), the structure was closed “indefinitely”, its term as a pet chunk of Americana capped at just under two years’ time.

I was lucky enough to photograph Vessel in person, creating day and night images that now seem as bizarre as launch-party pix of the Hindenburg or snapshots from Titanic. Photographers often catch a flavor of a time by accident, and many of our personal archives are populated by things we never thought of as perishable or mortal at the moment we shot them. Vessel is just one very public barometer of Dreams Gone Wrong, visions that deserve to be preserved inside our magic light boxes, either as tributes to our dreams or tombstones to our folly.

THE NEIGHBORHOOD KID

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S FORTUNATE FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS THAT THERE AREN’T MORE THAN A FEW WRITERS IN THE WORLD who can render a sense of place, of emotional truth, or of vivid detail as effectively as did Pete Hamill, the peerless New York journalist who passed earlier this week in this, 2020, the year of the Great Hibernation. Indeed, if the world was more generally peopled with people of his skill and passion, there would be no need of cameras. None.

This little hometown newspaper has, over the years, offered up brief sketches of the great shooters, from Walker Evans and Ansel to Diane Arbus, as well as gifted amateurs like Lewis Carroll. But this week, in my grief over the passing of a man who was a stranger to me personally, but, just as personally, as important as a blood relative, I realize that he, too, must be enshrined in a gallery of people who mostly shone in purely visual terms. Because, for those who live in and love the greater New York area, William Peter Hamill, Jr. did everything a good photographer strives to do, creating many images on the page that rival anything that even the best shooter could create.

Pete’s career as a columnist, novelist, essayist and teacher is the stuff of solid legend, but others have a far greater handle on the details of that story than I, like the New York Times, whose obituary on him is offered here. What I am talking about, in this forum, is the way he rendered the streets of Manhattan and the outer boroughs for those who had never had the privilege to walk them in person. He knew those streets the way a mother of twelve knows her kids…their names, their birthdays, their talents, their torments. In a city that never stands still long enough to linger over memory, Pete could dig through the strata of centuries in any neighborhood on the island, drilling all the way down to the gray schist that the Dutch stepped onto at the beginning of the entire mad experiment. Peeling those layers apart, he could place the territories of any immigrant from any tribe; where they landed, where they wandered, where they built legends, where they perished. In Hamill’s hands, the word nostalgia did not merely mean a sentimental ache for things lost or demolished. Certainly he kept score on what the city had sacrificed in its everlasting dash toward The Next Big Thing, but it was the details beyond mere longing that made his stories sing. It was what made him an indispensable guide for Ric Burns’ epic New York PBS miniseries, and Downtown: My Manhattan as indispensable a tool for newcomers as the Fodor’s travel guides. And it was what made even his darkest accounts of things great and small elicit, in the reader, a wry smile of recognition. “The tragic sense” he observed with true Irish fatalism, “opens a human being to the exuberant joys of the present.”

Like a photographer, Pete Hamill knew how to compose a frame to make your eye go directly to the most important thing. He knew where to lavish light and where to accent with darkness. He felt the value of negative space. He had a photo editor’s instinct for where to wield the cropping scissors. And he realized that the best human stories are simple, universal, direct things. Pete did with a Royal what the greatest photographers do with a Leica, but the result was the same. Immediacy. Truth. And the wisdom to ensure that his readers would always see The Big Picture.

HISTORY TAUGHT BY LIGHTNING

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ALONG WITH EVERYONE ELSE FROZEN IN PLACE BY 2020’s GREAT HIBERNATION, I’ve found myself riffing through my video collection in search of long-form diversion. In recent weeks, as New York struggled to emerge from the first massive crush of horror borne by the virus tragedy, I was seeking a kind of Manhattan-flavored comfort food, and unearthed my old copy of Ric (brother of Ken) Burns’ epic documentary on the history of the island from the time of the Dutch settlers to the final days of 1999. After 9/11, feeling that something incredibly important had been left unsaid, Ric went back into production on an eighth and final chapter,The Center Of The World, which told the detailed history of the specific lower Manhattan neighborhoods of “Ground Zero” as they existed before the attack, and concluding with a post-script on what was, at the time, the first stirrings of rebirth at the site. Re-watching this for the first time in years sent me into an archive of another kind: my own still images from roughly the same time frame.

Marian and I made our first pilgrimage to the site in 2011, right after access was opened to the memorial pools that were fashioned from the remains of the foundations of the twin towers of the original World Trade Center. The first replacement structure was not completely clad in glass at that time (see left), and entry to the area was by means of a ton of secured cyclone fencing and very long lines. Signs promised a yet-to-be-built memorial. Almost everything else in the rebirthing of the site was likewise still on the drawing board. The empty space across the street from the old 90 Church Street post office (which is the beige building in the middle of the lower image) would eventually become the great winged Oculus, the new entry point for the rebuilt PATH terminal and underground connector to various new business and retail complexes, themselves also under construction at the time. Barely ten years after a searing scar had been burned into the Manhattan streets and hearts, resurrection was already well under way. That’s New York, a city which would have been well served to steal its motto from the book title by Jesse Ventura, I Ain’t Got Time To Bleed.

The idea of rebirth is with me a lot these days, informing either the personal, immediate pictures I make in quarantine or the visual stories I’m hungry to find whenever it’s safe to venture out. I’m not an official chronicler of this mess, but I know we’ll create a vast and very human archive from all this misery. Like all things in life, it will pass, and we will creatively struggle with ways to mark the passage. To take measure of our own scar tissue, and the corrective surgery we will undergo to make the scars less obvious. In the meantime, even the pictures we make while isolated are important ones. See how long my hair got? Oh, sure, that was the home office we improvised. Yeah, this was my favorite window to look out: it kept me anchored.

2011: From left: the lower portion of the new World Trade Center One tower, the 90 Church Street post office, and, in back of the memorial pool, the site where the Oculus PATH terminal would be built just a few years later.

Photographs are as remote or as personal as we determine them to be, but, even at their most introspective, they will say something about the human condition in general. This is how I got through. And maybe it’s similar to how you did it. There will be remembrance, but there will be no lingering over smoking ruins. We ain’t got time to bleed. Woodrow Wilson once compared the relatively new art of motion pictures to “teaching history by lightning”. That’s the pace now. We move rapidly from the role of mourners to the role of builders. And we will etch the resulting lightning inside our cameras, to simply state, we passed this way.

A BREAK IN THE CHAIN

By MICHAEL PERKINS

YOU RECOGNIZE THE ELEMENTS OF THEIR STRANGE VISUAL SIGNATURES AT ONCE: garish neon; outsized, surreal props: homemade window signs: and, always, for the storefronts of aging or vanishing businesses, the feeling that this is the creation of a single owner, not a faceless chain. It’s the Great American Mom ‘n’ Pop, and it is always flitting near the edge of extinction. And like all things endangered, it is fitting fodder for the photographer…for although these strange displays don’t include the standard features of the human face, yet still a human portrait of sorts can be made from their humble elements.

If you ever get the chance, thumb through an enormous volume called Store Front: The Disappearing Face of New York by James and Karla Murray (Gingko Press, 2008). Shot on simple 35mm film, this amazing collection offers both images and backstories from all five boroughs in the greater NYT metro, organized by region. The caption data for the pictures is often the personal remembrances of the most recent operators of the various neighborhood’s delis, dry cleaners, beauty salons, supply houses and markets, most of them in continuous operation for most or all of the twentieth century, many closing up forever even as the book was going to press. The “front” is a kind of short story, a miniature play about who we were, what we sought, what we settled for. Often the buildings have risen or fallen with their respective neighborhoods, their entrances falling prey to crime, time, neglect. Several owners lament not being able to get the parts to keep their neon signs in repair. Others wish they could add a new awning, a fresh coat of paint. And always, as the fronts wink out, regentrification rears its trendy head. But it doesn’t bring new good times for the old place. Instead, it erases their stories…with apartment blocks, Pizza Huts, a Verizon store.

The image seen here, along Central Avenue is Phoenix, Arizona, boasts of (at least) a world of cheese, at a deli which is short on space but long on local flavor. In the American Southwest, as compared to other cities, neighborhoods don’t often get to live long enough to become “venerable” or “historic”, such is the short loop between grand openings and final swings of the wrecking ball. In more traditional urban spaces, everything old is occasionally new again. In Phoenix, it’s old, and then….just gone. The insanely disproportionate worship of the new and shiny in this part of the country can be exhilarating, but the real loss it engenders is sad and final in the way that doesn’t always happen back east. As a consequence, urban chroniclers in this neck o’ the desert must keep their cameras forever at the ready. You can never assume that you’ll get that picture the next time you swing through the neighborhood. Because the neighborhood itself may not be around.

For photographic purposes, I believe that storefronts are best shot straight-on (rather than at an angle) so that their left-to-right information reads like a well-dressed theatre stage. This also makes us look at them differently than we do as either pedestrians or drivers, where they tend to slide along the edge of our periphery largely unnoticed. Some of them benefit from being decorated by the figures of passersby: others appear more poignant standing alone. The main thing, if for no other reason except to create a break in the “chain migration”, is to maintain a record. There is a reason why so many “then and now” books of urban photographs are so jarring in their contrasting images. We live so quickly that we simply do not record our environment even through the daily process of using it. We need reminders for reference, even on the things that we should be eventually letting go of. And the camera puts down mileposts in a compelling way. It marks. It delineates, stating in concrete terms, we were that, and now we’re this. I believe in getting out that tape measure on occasion. I think it matters.

ARCHITECTS OF HOPE

Part of Jose Maria Sert’s soaring mural American Progress (1937) above the main information desk just inside the entrance to 30 Rockefeller Plaza.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE EROSION AND COLLAPSE OF THE GREAT AMERICAN URBAN INFRASTRUCTURES of the 20th century is more than bad policy. It is more than reckless. It is also, to my mind, a sin against hope.

As photographers, we are witness to this horrific betrayal of the best of the human spirit. The pictures that result from this neglect may, indeed, be amazing. But we capture them with a mixture of sadness and rage.

Hope was a rarity in the early days of the Great Depression. Prosperity was not quite, as the experts claimed, “right around the corner.” And yet, a strategy arose, in private and federal project alike, that offered uplift and utility at the same time. People were put to work making things that other people needed. The nation erected parks, monuments, utilities, forests, and travel systems that turned misery to muscle and muscle to miracle. Millionaires used their personal fortunes to create temples of commerce and towers of achievement, hiring more men to turn more shovels. Hope became good business.

One of the gleaming jewels of the era was, and is, the still-amazing Rockefeller Plaza in New York, which, in its decorative murals and reliefs, lionized the working man even as it put bread on his table. The dignity of labor was reflected across the country in everything from newspaper lobbies to post office portals, giving photographers the chance to chronicle both decline and recovery in a country brought only briefly to its knees.

Today, the information desk at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, home of NBC studios, still provides a soaring tribute to the iron workers and sandhogs who made it possible for America to again put one foot in front of the other, marching, not crawling, back into the sunlight. It still makes a pretty picture, as can thousands of such surviving works across the country. Photographing them in the current context of priceless inheritance offers a new way to thank the bygone architects of hope.

7/4/15: OH, SAY, CAN YOU SEE?

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FOR AS LONG AS THERE HAS BEEN PHOTOGRAPHY, the United States of America has flown some version of the Stars and Stripes, a banner that has symbolized, in cloth and thread, what we profess and hope for ourselves as one of the world’s experiments in self-government. That argues for the flag being one of the most photographed objects in history, and, therefore, one of the most artistically problematic. Those things that are visualized most, by most of us, endure the widest extremes in interpretation, as all symbols must, and observing that phenomenon as it applies to the flag is both fascinating and frustrating.

Fascinating, because the flag can embody or evoke any emotion, any association, any memory, providing a gold mine for photographers who always must look beyond the mere recording of things to their underlying essences. Frustrating, because that task can never be complete, in that there can be no definitive or final statement about a thing that resonates so intensely, so personally with a diverse nation. Photographing the flag is always new, or, more precisely, it can always be made new.

The problem with fresh photographic approaches to the flag is really within ourselves. The banner is so constantly present, on public buildings, in pop culture, even as commentary, that it can become subliminal, nearly invisible to our eye. Case in point: the image at left of the front facade to Saks’ in Manhattan. The building is festooned in flags across its entire Fifth Avenue side, which is, being across the street from Rockefeller, a fairly well-trafficked local. And yet, in showing this photo to several people from the city, I have heard variations on “where did you take that?” or “I never noticed that before” even though the display is now several years old.

And that’s the point. Saks’ flags have now become as essential a part of the building as its brick and mortar, so that, at this point, the only way the building would look “wrong” or “different” is if the flags were suddenly removed. Training one’s eye to see afresh what’s just been a given in their world is the hardest kind of visual re-training, and the American flag, visually inexhaustible as a source of artistic interpretation, can only be blunted by how much we’ve forgotten to see it.

Photography has found a cure for sharpness, clarity, exposure, even time itself. But it can’t compensate for blindness. That one’s on us.

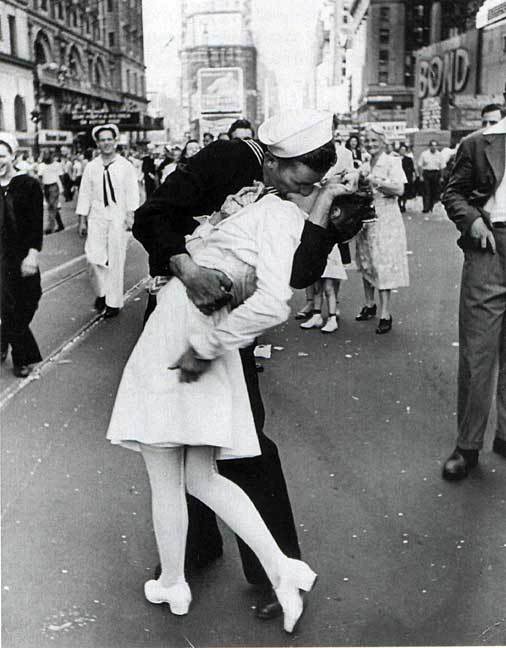

A KISS ON VETERAN’S DAY

A PICTURE, WHEN IT TRULY COMMUNICATES, isn’t worth a thousand words. The comforting cliché notwithstanding, a great picture goes beyond words, making its emotional and intellectual connection at a speed that no poet can compete with. The world’s most enduring images carry messages on a visceral network that operates outside the spoken or written word. It’s not better, but it most assuredly is unique.

Most Veteran’s Days are occasions of solemnity, and no amount of reverence or respect can begin to counterbalance the astonishing sacrifice that fewer and fewer of us make for more and more of us. As Lincoln said at Gettysburg, there’s a limit to what our words, even our most loving, well-intended words, can do to consecrate that sacrifice further.

But images can help, and have acted as a kind of mental shorthand since the first shutter click. And along with sad remembrance should come pictures of joy, of victory, of survival.

Of a sailor and a nurse.

Alfred Eisenstaedt, the legendary photojournalist best known for his decades at Life magazine, did, on V-J day in Times Square in 1945, what millions of scribes, wits both sharp and dull, couldn’t do. He produced a single photograph which captured the complete impact of an experience shared by millions, distilled down to one kiss. The subjects were strangers to him, and to this day, their faces largely remain a mystery to the world. “Eisie”, as his friends called him, recalled the moment:

In Times Square on V.J. Day I saw a sailor running along the street grabbing any and every girl in sight. Whether she was a grandmother, stout, thin, old, it didn’t make a difference. I was running ahead of him with my Leica, looking back over my shoulder, but none of the pictures that were possible pleased me. Then suddenly, in a flash, I saw something white being grabbed. I turned around and clicked the moment the sailor kissed the nurse. If she had been dressed in a dark dress I would never have taken the picture. If the sailor had worn a white uniform, the same. I took exactly four pictures. It was done within a few seconds.

Those few seconds have been frozen in time as one of the world’s most treasured memories, the streamlined depiction of all the pent-up emotions of war: all the longing, all the sacrifice, all the relief, all the giddy delight in just being young and alive. A happiness in having come through the storm. Eisie’s photo is more than just an instant of lucky reporting: it’s a toast, to life itself. That’s what all the fighting was about anyway, really. That’s what all of those men and women in uniform gave us, and still give us. And, for photographers the world over, it is also an enduring reminder from a master:

“This, boys and girls, is how it’s done.”

THE JOY OF BEING UNIMPORTANT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

I HAVE AT LEAST TWO WOMEN IN MY LIFE WHO WORRY if I am sufficiently entertained whenever I am borne along on their ventures into various holy lands of retail. Am I waiting too long? Am I bored at being brought along? Would I like to go somewhere else and rejoin them later at an appointed time and place?

Answers: No to questions 1, 2 and 3…so long as I have my hands on a camera.

I can’t tell you how many forays into shoe emporiums, peeks into vintage stores and rambles through ready-to-wear shops have provided me with photographic material, mainly because no one would miss me if I were to disappear for a bit, or for several days. And, as I catalogue some of the best pickings I’ve plucked from these random wanderings, I find that many of them were made possible by the simple question, “do you mind amusing yourself while I try this on?” Ah, to have no authority or mission! To let everything pale in importance when compared to the eager search for pictures! To be of so little importance that you are let off the leash.

The above image happened because I was walking with my wife on the lower east side of Manhattan but merely as physical accompaniment. She was looking for an address. I was looking for, well, anything, including this young man taking his cig break several stories above the sidewalk. He was nicely positioned between two periods of architecture and centered in the urban zigzag of a fire escape. Had I been on an errand of my own, chances are I would have passed him by. As I was very busy doing nothing at all, I saw him.

Of course, there will be times when gadding about is only gadding about, when you can’t bring one scintilla of wisdom to a scene, when the light miracles don’t reveal themselves. Those are the times when you wish you had pursued that great career as a paper boy, been promoted to head busboy, or ascended to the lofty office of assistant deacon. I’m telling you: shake off that doubt, and celebrate the glorious blessing of being left alone…to imagine, to dream, to leave the nest, to fail, to reach, to be.

Photography is about breaking off with the familiar, with the easy. It’s also having the luck to break off from the pack.

OH, IT’S HIDEOUS. I LOVE IT.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THERE MAY BE NO RULES LEFT TO BREAK IN PHOTOGRAPHY, in that everybody is comfortable doing absolutely anything….compositionally, conceptually, technologically…to get the picture they want. Maybe that’s always the way it’s been, seeing as the art of image-making, like the science of breeding apple trees, has always grown faster and stronger through cloning and grafting. Hacks. Improvisations. “Gee-What-If”s.

Shots in the dark.

Recently I walked out into the gigantic atrium that connects all of the original buildings of the Morgan Library complex in NYC to get a good look at the surrounding neighborhood of big-shouldered buildings. I was fascinated by the way my wide-angle lens seemed to line up the horizontal grid lines of the atrium with the receding lines of the towers and boxes down the block. Only one thing bothered me about the result: the color, or rather, the measly quality of it.

A rainy day in Manhattan is perhaps the final word on rainy days. Some colors, like the patented screaming yellow of a New York cab, or the loud neon reds of bodegas, are intensified into a romantic wash when the drops start. This view, however, was just a bland mash of near-color. If the neighborhood was going to look dour anyway, I wanted it to be dour-plus-one. Thing is, I made this, ahem, “artistic” decision after I had already traveled 3,000 miles back home. In the words of Rick Perry, whoops.

Time to hack my way to freedom. I remembered liking the look of old Agfa AP-X film in a filter on my iPhone, so I filled the screen of my Mac with the bland-o image, shot the screen with the phone, applied the filter, uploaded the result back into the Mac again, and twisted the knobs on the new cheese-grater texture I had gained along the way. At least now it looked like an ugly day….but ugly on my terms. Now I had the kind of rain-soaked grayscale newspaper tones I wanted, and the overall effect helped to better meld the geometry of the atrium and the skyline.

No rules? Sure, there’s still at least one.

Get the shot.