SAVING FACE

Looking West, 2016. A portrait shot with a Lensbaby Composer Pro, an effects lens with a moveable “sweet spot” of selective focus.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE CREATIVE USE OF SHARPNESS is one of the key techniques in photography. From the beginning of the medium, it’s been more or less conceded that not everything in an image needs to register at the same level of focus, that it can be manipulated to direct attention to the essence of a photograph. It’s always about telling the viewer to look here, ignore this, regard this as important.

This selective use of focus applies to the human face no less than to any other element in a composition. It’s strange that photography drew so strongly on painting in its early years without following the painter’s approach to portraits…..that is, that individual parts of a face can register in different degrees of sharpness, just like anything else in the frame. From the earliest days of photo-portraiture, there seems to have been an effort to show the entire face in very tight focus, de-emphasizing backgrounds by hazing them into a soft blur. It took a while before photography saw itself as a separate art, and thus this “always” rule only became a “sometimes” rule over a protracted period of time.

The Pictorialism fetish of the early 20th century, which avidly imitated the look of paintings, went completely the other direction, generating portraits that were almost uniformly soft, as if shot through gauze, or, you guessed it, painted on canvas. In recent years, shooters have begun a new turn toward a kind of middle stance, with the selective use of sharpness in specific parts of a face, say an eye or a mouth. It’s more subtle than the uniform crispness of olden days, and affords shooters a wider range of expression in portraits.

Some of this has been driven by technology, as in the case of the Lensbaby lenses, which often have a tack-sharp “sweet spot” at their center, with everything else in the frame fanning outward to a feathery blur. Additionally, certain Lensbabies, like the Composer Pro, are mounted on a kind of ball turret, allowing the user to rotate the center of the lens to place the sweet spot wherever in the image he/she wants. This makes it possible, as in the above shot, for parts of objects that are all in the same focal plane to be captured at varying degrees of sharpness. Note that, while all of the woman’s face is the same distance from the camera, only her eyes and the right side of her face are truly sharp. This dreamlike quality has become popular with a new breed of portraitists, and, indeed, there are already wedding photographers who advertise that they do entire events exclusively with these kinds of lenses.

The face is a composition element, and, as such, benefits from a flexible approach to focus. One man’s blur is another man’s beautification.

SEE DICK THINK.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

FORGET BLOWN EXPOSURES, SHAKY SNAPSHOTS, AND FLASH-SATURATED BLIZZARDS. The hardest thing to avoid in the taking of a picture is winding up with a picture full of other people taking a picture. Hey, democracy in art, power to the people, give every man a voice, yada yada. But how has it become so nearly impossible to keep other photographers from leaning in, crossing through, camping out or just plain clogging up every composition you attempt?

And is this really what I’m irritated about?

Maybe it’s that we can all take so many pictures without hesitation, or, in many cases, without forethought or planning, that the exercise seems to have lost some of its allure as a deliberate act of feeling/thinking/conceiving. Or as T.S. Elliot said, it’s not sad that we die, but that we die so dreamlessly. It’s enough to make you seek out things that, as a photographer, will actually force you to slow down, consider, contemplate.

And one solution may lie in the depiction of other people who are, in fact, taking their time, creating slowly, measuring out their enjoyment in spoonfuls rather than buckets. I was recently struck by this in a visit to the beautiful Brooklyn Botanical Gardens on a slow weekday muted by overcast. There were only a few dozen people in the entire place, but a significant number of those on hand were painters and sketch artists. Suddenly I had before me wonderful examples of a process which demanded that things go slowly, that required the gradual evolution of an idea. An anti-snapshot, if you will. And that in turn slowed me down, and helped me again make that transition from taking pictures to making them.

Picturing the act of thought, the deep, layered adding and subtracting of conceptual consequence, is one of the most rewarding things in street photography. Seeing someone hatch an idea, rather than smash it open like a monkey with a cocoanut does more than lower the blood pressure. It is a refresher course in how to restore your own gradual creativity.

FACING UP

By MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE LUXURY THAT PAINTERS HISTORICALLY ENJOYED OVER PHOTOGRAPHERS was the pure prolonged incubation time between their conception of a thing and its realization on the canvas. Whatever else painting is, it is never an instantaneous process, something that is especially true for portraits. The daubing of strokes, mixing of paint, the waiting for the light, and the waiting for the model to arrive (take a bathroom break, eat dinner, etc.) all contribute to painting’s bias toward the long game. The process cannot be hurried. There is no pigmentary equivalent of the photographic snap shot. Patience is a virtue.

The first photographs of people were likewise a gradual thing, with extended exposure times dictated by the slow speed of early plate and film processes. Once that obstacle was overcome, however, it became a simple thing to snap a person’s face in less and less time. Today, outside of the formal studio experience, most of us freeze faces in record timae, and that may be a bit of a problem in trying to create a true portrait of a person.

Portraits are more than mere recordings, since the subject matter is infinitely more complex than an apple or a vase of flowers. The daunting task of trying to capture some essential quality, some inner soulfulness with a mechanical device should make us all stop and think a little, certainly a little longer than a fraction of a second. Portraits at their best are a kind of psychoanalysis, an negotiation, maybe even a co-creation between two individuals. The best portraitists can be said to have produced a visible relic of something invisible. Can that be done in the instant that it takes to shout “cheese” at somebody?

And if the process of portraiture is, as I argue, an innately personal thing, how can we trust the “street portraits” that we steal from the unsuspecting passerby? Are any of these images revelatory of anything real, or have we only snatched a moment from the onrushing current of a person’s life? Taking the argument away from the human face for a moment, if I take a picture of a single calendar date page, have I made a commentary on the passage of time, or merely snapped a piece of paper with a number on it?

Painters have always been forced into some kind of relationship with their subjects. Some fail and some succeed, but all are approached with an element of planning, of intent. By contrast, the photographer must apprehend what he wants from a face in remarkably short time, and hope his instinct can make an intimate out of a virtual stranger.

MAKING LIGHT OF THE SITUATION

BY MICHAEL PERKINS

IN PORTRAITS, PHOTOGRAPHERS SOMETIMES HAVE TO SUBSTITUTE INTIMACY FOR TECHNICAL PERFECTION. We understandably want to come as near as possible to meticulously modulated light in telling the story of a face, and so we try to ride the line between natural, if inadequate light, and light which is shaped so much that we dull the naturalness of the moment.

It’s a maddening tug of war. If we don’t intervene, we might make an image which is less than flattering, or, worse, unfit for publication. If we nib in too much, we get a result whose beauty can border on the sterile. I find that, more often than not, I lean toward the technically limited side, choosing to err in favor of a studied snapshot rather than a polished studio look. If the face I’m shooting is giving me something real, I worry more about throwing a rock into that perfect pond with extra tinkering.

If my subject is personally close to me, I find it harder, not easier, to direct them, lest the quality I’m seeing in their natural state be replaced by a distancing self-consciousness. It puts me in the strange position of having to wait until the situation all but gifts me with the picture, as adding even one more technical element can endanger the feel of the thing. It’s times like this that I’m jammed nose-up against the limits of my own technical ability, and I feel that a less challenged shooter would preserve the delicacy of the situation and still bring home a better photograph.

In the above frame, the window light is strong enough to saturate the central part of my wife’s face, dumping over three-fourths of her into deep shadow. But it’s a portrait. How much more do I need? Would a second source of light, and the additional detail it would deliver on the left side of her head be more “telling” or merely be brighter? I’m lucky enough in this instance for the angle of the window light to create a little twinkle in her eye, anchoring attention in the right place, but, even at a very wide aperture, I still have to crank ISO so far that the shot is grainy, with noise reduction just making the tones flatter. It’s the old trade-off. I’m getting the feel that I’m after, but I have to take the hit on the technical side.

Then there was the problem that Marian hates to have her picture taken. If she hadn’t been on the phone, she would already have been too aware of me, and then there goes the unguarded quality that I want. I can ask a model to “just give me one more” or earn her hourly rate by waiting while I experiment. With the Mrs., not so much.

Here’s what it comes down to: sometimes, you just have to shoot the damned thing.

EAVES-EDITING

by MICHAEL PERKINS

ONE OF THE SIDE BENEFITS OF PHOTOGRAPHY is that you don’t always have to pick your own subject. Sometimes someone else’s idea of a potentially good image can be yours as well. You simply camp yourself right next to where they’re working and pick off your own shots of their project. Assuming that everyone’s polite and there are no issues of neighborly nibbing, it can work. Just ask anyone who’s clicked away at a presidential press conference or the sudden exit of a celebrity through a side entrance.

Of course, when literally dozens of cameras are trained on a single event, its likely that everyone will come away with the same photos, or very nearly. The moment the prime minister points to drive home his main point, click. The instant when the judges place the tiara on the winning Miss Tomato Paste candidate, click. Sometimes, however, you can kind of “eaves-edit” on just one other shooter’s set-up and edit the shots a different way than he does. You’re not running the session, but you could come away with a better result than he does, based on your choices.

I recently came upon a man shooting a girl in the streets of a kind of faux-village retail environment in Sedona, Arizona. Obviously, the main feature was the lady’s infectious and natural smile. As I came quietly upon them, however, Mr. Cameraman was having a problem keeping that smile from exploding into a full-blown laughing fit. Ms. Subject, in short, had the mad giggles.

Now, from that point onward, I have no idea of what he went home with in the way of a final result, as I had decided that the crack-ups would make better pictures than a merely sweet set of candids. It just seemed more human to me, so I only shot the moments in which she couldn’t compose herself, and took off from there.

I didn’t want to overstay my welcome, so I snapped my little chunk of Mr. Cameraman’s moment and sneaked off, like fast. As I slinked away, I could still hear Ms. Subject telling him, through fits of laughter, “I am so sorry.” She may have been, but I wasn’t.

THE REVEAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHERS HAVE MANY INSTANCES IN WHICH IT’S HEALTHY TO HAVE A LITTLE HUMILITY, and the biggest one probably is in the decision to depict a human face. It’s the most frequently performed operation in all of photography, and many of us only approach perfection in it a handful of times, if ever. The face is the essence of mystery, and learning how to draw the curtain away from it is the essence of mastery.

Nothing else that we will shoot fights so hard to maintain its inscrutability. It is easier to accurately photograph the microbes that swarm in a drop of water than to penetrate the masks that we manufacture. Even the best portrait artists might never show all of what their subject’s soul really looks like, but sometimes we can catch a fleeting glimpse, and getting even that little peek is enough to keep you behind a camera for a lifetime. It is everything.

Yousuf Karsh, the portraitist who can be said to have made the definitive images of Winston Churchill, Audrey Hepburn, JFK, Ernest Hemingway, and countless other notables, said “within every man and woman. a secret is hidden, and, as a photographer, it is my task to reveal it if I can.” Sounds so simple, and yet decades can go into learning the difference between recording a face and rendering its truths. Sometimes I think it’s impossible to photograph people who are strangers to us. How can that ever happen? Other times I fear that it’s beyond our power to create images of those we know the most intimately. How can we show all?

The human face is a document, a lie, a cipher, a self-created monument, an x-ray. It is the armor we put on in order to do battle with the world. It is the entreaty, the bargain, the arrangement with which we engage with each other. It is a time machine, a testimony, a faith. Photographers need their most exacting wisdom, their most profound knowledge of life, to attempt The Reveal. For many of us, it will always remain that….an attempt. For a fortunate few, there is the chance to freeze something eternal, the chance to certify humanity for everyone else.

Quite a privilege.

Quite a duty.

JOY GENERATORS

I could pose this rascal all day long, but I can’t create what he can freely give me. 1/40 sec., f/3.2, ISO 500, 35mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

IT’S A TITANIC CLICHE, BUT RESOUNDINGLY TRUE: if you want a child to reveal himself to you photographically, get out of his way.

The highly profitable field of child portrait photography is being turned on its head, or more precisely, turned out of the traditional portrait studio, by the democratization of image making. As technical and monetary barriers that once separated the masses from the elite few are vanishing from photography, every aspect of formal studio sittings is being re-examined. And that means that the $7.99 quickie K-Mart kiddie package is going the way of the dodo. And it’s about bloody time.

Making the subject fit the setting, that is, molding someone to the props, lighting or poses that are most convenient to the portraitist seems increasingly ridiculous. Thing is, the “pros” who do portrait work at the highest levels of the photo industry have long since abandoned these polite prisons, with Edward Steichen posing authors, politicians and film stars in real-life settings (including their own homes) as early as the 1920’s, and Richard Avedon pulling models out of the studio and into the street by the late 1940’s. So it’s not the best photographers who insist on perpetuating the restrictive environment of the studio shoot.

No, it’s the mills, the department and discount stores who still wrangle the kiddies into pre-fab backdrops and watch-the-birdie toys, cranking out one bland, safe image after another, and veering the photograph further and further from any genuine document of the child’s true personality. This is what has to change, and what will eventually result in something altogether different when it comes to kid portraiture.

Children cannot convey anything real about themselves if they are taken out of their comfort zones, the real places that they play and explore. I have seen stunning stuff done with kids in their native environment that dwarfs anything the mills can produce, but the old ways die hard, especially since we still think in terms of “official” portraits, as if it’s 1850 and we have a single opportunity to record our existence for posterity. There really need be no “official” portrait of your child. He isn’t U.S. Grant posing for Matthew Brady. He is a living, pulsating creature bent on joy, and guess what? You know more about who and what he is than the hourly clown at Sears.

I believe that, just as adult portraiture has long since moved out of the studio, children need also to be released from the land of balloons and plush toys. You have the ability to work almost endlessly on getting the shots of your children that you want, and better equipment for even basic candids than have existed at any other period in history. Trust yourself, and experiment. Stop saying “cheese”, and get rid of that damned birdie. Don’t pose, place, or position your kids. Witness these little joy generators in the act of living. They’ll give you everything else you need.

TELLING THE TRUTH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PICK ANY PHOTOGRAPHIC ERA YOU LIKE, and most of the available wisdom (or literature) will concentrate on honoring some arbitrary list of rules for “successful” pictures. On balance, however, relatively few tutorials mention the needful option of breaking said rules, of making a picture without strict adherence to whatever commandments the photo gods have handed down from the mountain. It’s my contention that an art form defined narrowly by mere obedience is bucking for obsolescence.

It’d be one thing if minding your manners and coloring inside the lines guaranteed amazing images. But it doesn’t, any more than the flawless use of grammar guarantees that you’ll churn out the great American novel. Photography was created by rebels and outlaws, not academics and accountants. Hew too close to the golden rules of focus, exposure, composition or subject, and you may inadvertently gut the medium of its real power, the power to capture and communicate some kind of visual verity.

A photograph is a story, and when it’s told honestly, all the technical niceties of technique take a back seat to that story’s raw impact. The above shot is a great example of this, although the masters of pure form could take points off of it for one technical reason or another. My niece snapped this marvelous image of her three young sons, and it knocked me over to the point that I asked her permission to make it the centerpiece of this article. Here, in an instant, she has managed to seize what we all chase: joy, love, simplicity, and yes, truth. Her boys’ faces retain all the explosive energy of youth as they share something only the three of them understand, but which they also share with anyone who has ever been a boy. This image happens at the speed of life.

I’ve seen many a marvelous camera produce mundane pictures, and I’ve seen five-dollar cardboard FunSavers bring home shots that remind us all of why we love to do this. Some images are great because we obeyed all the laws. Some are great because we threw the rule book out the window for a moment and just concentrated on telling the truth.

You couldn’t make this picture more real with a thousand Leicas. And what else are we really trying to do?

STEALTH

By MICHAEL PERKINS

AT A PARTY, THERE ARE DISTINCT ADVANTAGES TO NOT BEING AN “OFFICIAL” PHOTOGRAPHER. You could probably catalogue many of them yourself with no strain. Chief among the perks of being an amateur (can we get a better word for this?) is that you are the captain of your own fate. You shoot what you want, when you want. Your arrival on the scene is not telegraphed by stacks of accompanying cases, light fixtures, connecting cords or other spontaneity killers that are essential to someone who has been “assigned” to an event. Your very unimportance is your license to fly, your ticket to liberation. Termed honestly (if unkindly), your work just doesn’t matter to anyone else, and so it can mean everything to you. Yay.

One of the supreme kicks I derive from going to events with my wife is that I can make her forget I’m there. I mean, as a guy with a camera. She has the gift of being able to submerge completely into the social dynamics of wherever she is, so she is not thinking about when I may elect to sneak up and snap her. Believe me, when you live with a beautiful woman who also hates to have her picture taken, this is like hitting the trifecta at Del Mar. At 20 to 1.

Free from the constraints of being “on the job”, I enjoy a kind of invisibility at parties, since I use the fastest lenses I can and no flash, ever, ever, ever. I do not call attention to myself. I do not exhort people to smile or arrange them next to people that they may or may not be able to stand. The word “cheese” never leaves my lips. I take what the moment gives me, as that is often richer than anything I might concoct, anyway. Working with a DSLR is a little more conspicuous than the magical invisibility of a phone camera, which people totally ignore, but if I am cagey, I can work with an “official” camera and not be perceived as a threat. Again, with a woman who (a) looks great and (b) doesn’t like how she looks in pictures, this is nirvana.

Candid photography is all about the stealth. It’s not about warning or prepping people that, attention K-Mart shoppers, you’re about to have your picture took. The more you insert yourself into the process (look over here! big smiiiiile!) the more you interrupt the natural rhythm that you set out to capture. So stop working against yourself. Be a happy sneak thief. Like me.

THE EYES (DON’T NECESSARILY) HAVE IT

By MICHAEL PERKINS

A QUICK GOOGLING OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC UNIVERSE THESE DAYS will turn up a number of sites dedicated to “faceless portraits”, if there can, strictly speaking, be such a thing (and I believe there can). In a recent post entitled Private, Not Impersonal, I explored the phenomenon in which photographers, absent the features that most easily chronicle their subjects’ personalities, imply them, merely through body language, composition, or lighting. At the time I wrote the post, I was unaware how widespread the practice of faceless portraits had become. In fact, it’s something of a rage. Hmm. The very thought that, even by accident, I could be aligned with something hip, is, by turns, both terrifying and hilarious.

Thing is, photographs, as the famous curator John Szarkowki remarked, both conceal and reveal, and there is nothing about the full depiction of a human face that guarantees that you’re learning or knowing anything about the subject in frame. We are all to practiced at maintaining our respective masks for many portraits to be taken, ha ha, at face value. Cast your eye back through history and you will find dozens of compelling portraits, from Edward Steichen’s silhouettes of Rodin to Annie Leibovitz’ blurred dance photos of Diane Keaton, that preserve some precious element of humanity that a formal, face-on sitting cannot deliver. Call it mystery, for lack of a more precise word.

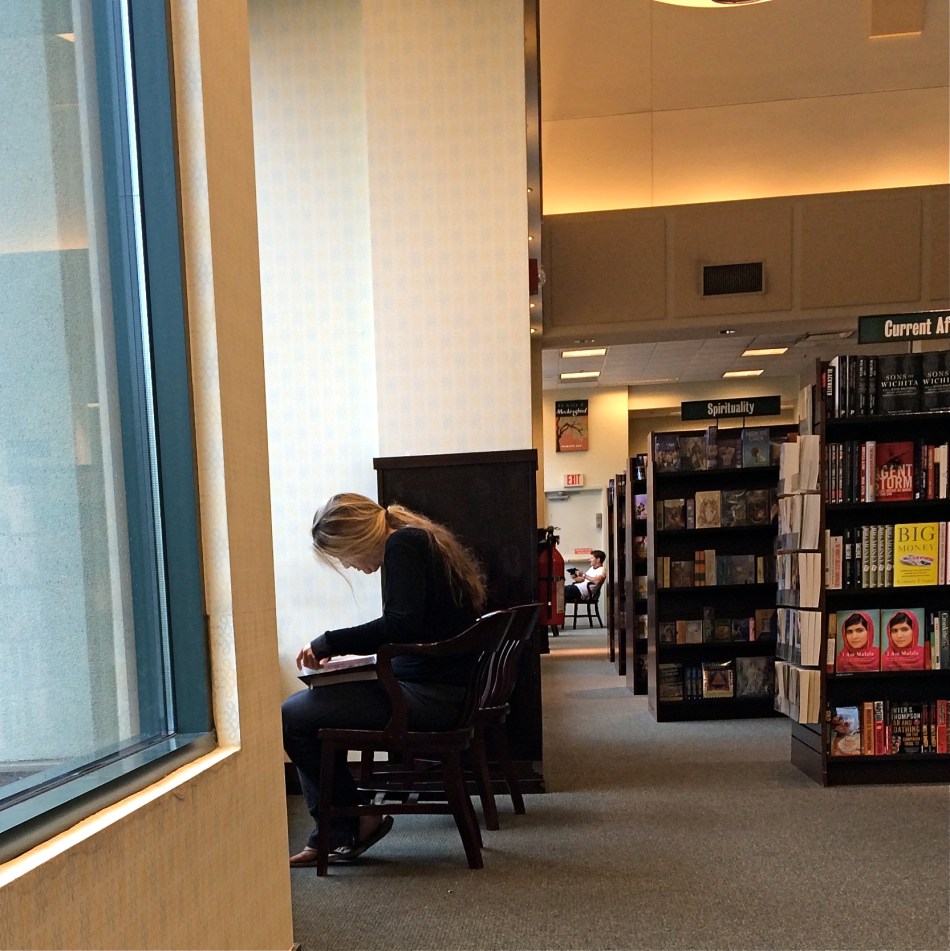

In the above frame, the subject whose face I myself never even saw gave me something wonderfully human, about reading in particular, but about enchantment in general. She is furiously busy discovering another world, a world the rest of us can only guess at, seeping up from her book. Her entire body is an inventory of emotional textures…of relaxation, attentiveness, of both being in the present and so completely someplace else. Framing her to include the negative spaces of the window, the carpet and the wider bookstore isolate her further from us, but not in a negative way. She wants to be apart; she is on a journey.

My “girl with the flaxen hair” was unaware of me, and I shot furtively and quickly to make sure I didn’t break the spell she was under. It was the least I could do in gratitude for a chance to witness her adventure. Looking back, I think she provided more than enough magic without revealing a single fragment of her face. Seeing is selecting, and I had been given all I needed to do both.

Click and be gone.

PRIVATE, NOT IMPERSONAL

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PORTRAITURE IS RATHER NARROWLY DEFINED BY MOST PHOTOGRAPHERS as an interpretation of a person’s face, the place wherein we believe that most of his/her humanity resides. The wry smile. The upturned eyebrow. The sparkling eye. It’s all there in the features, or so we seem to profess by valuing the face over nearly all other physical features.We stipulate that there are notable exceptions where the body carries most of the message, as in crowd scenes, sports action, or combat shots. But for the most part, we let the face hold the floor (and believe me, after a few misspent nights, my face has held the floor plenty of times).

It’s interesting, however, in an age where privacy has become a premiere issue, and in which the camera’s eye never blinks, that we don’t explore the narrative power of bodies as much as we do faces. The body, after all, carries out the intentions of the mind no less than does the face. It executes the physical action that the mind intends, and so creates a space that reveals that intention. Just like a face. And yet, we have a decidedly pro-face bias in our portraiture, to the point that a portrait that does not include a face is thought by some not to be a portrait at all.

But let’s keep the discussion, and our minds, open, shall we? I love to work with random crowds, and I like nothing better than to immortalizing emotions in a nice face-freeze. However, I strongly maintain that, absent those obvious visual “cues”, a body can carry a storyline all by itself, even enhance the charm or mystery involved in trying to penetrate the personality of our subjects.

Consider for a moment how many amazing nude studies you’ve seen where the subject’s face is completely, even deliberately obscured. Does the resulting image lack in power, or does the power traditionally residing in the face just transfer to the rest of the composition?

Portraits (I insist on calling them that) that are more “private” for being faceless are no more “impersonal” than if the subject was flashing the traditional “cheese!” and beaming their personality directly into the lens.

Photography is not about always getting the vantage point that we want, but maximizing the one we have at hand. And sometimes, taking away a face also strips away a mask. But beyond that, why not actually court mystery, allow ourselves to trust our audiences to supply mentally what we reserve visually?

Ask yourself: what does a photograph of understatement look like?

SYMBOLS (For Father’s Day, 2014)

By MICHAEL PERKINS

PHOTOGRAPHY IS, ALTERNATIVELY, AN ART OF BOTH DOCUMENTATION AND SUGGESTION. It is, of course, one of its essential tasks to record, to mark events, comings, goings, arrivals, and passings. That’s basically a reporter’s function, and one which photographers have served since we first learned to trap light in a box. The other, and arguably more artistic task, is to symbolize, to show all without showing everything. And on this Father’s Day (as on every one), we honor our parents by taking photographs which address both approaches.

For many years, I have taken the obvious path by capturing the latest version of Dad’s face. It’s an ever-changing mosaic of effects, which no photographer/storyteller worth his salt can resist. But in recent years, I also am trying to symbolize my father, to make him stand not only for his own life, but for the miles traveled by all parents. For this task, a face is too specific, since it is so firmly anchored to its own specific myths and legends. To make Dad emblematic, not just as a man but rather as “Man”, I’ve found that abstracting parts of him can work a little better than a simple portrait.

These days, Dad’s hands are speaking to me with particular eloquence. They bear the marks of every struggle and triumph of human endeavor, and their increasing fragility, the etchings on the frail envelope of mortality, are especially poignant to me as I enter my own autumn. I have long since passed the point where I seem to have his hands grafted onto the ends of my own arms, so that, as I make images of him, I am doing a bit of a trending chart on myself as well. In a way, it’s like taking a selfie without actually being in front of the camera.

Hands are the human instruments of deeds, change, endeavor, strength, striving. Surviving. They are the archaeological road map of all one’s choices, all our grand crusades, all our heartbreaking failures and miscalculations. Hands tell the truth.

Dad has a great face, a marvelous mix of strength and compassion, but his hands…..they are human history writ large.

Happy Father’s Day, Boss.

EYES WITHOUT A FACE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CHILDREN ARE THE GREATEST DISPLAY SPACES FOR HUMAN EMOTION, if only because they have neither the art nor the inclination to conceal. It isn’t that they are more “honest” than adults are: it’s more like they simply have no experience hiding behind the masks that their elders use with such skill. Since photographs have to be composed within a fixed space or frame, our images are alternatively about revelation and concealment. We choose how much to show, whether to discover or hoard. That means that sometimes we tell stories like adults, and sometimes we tell them like children.

The big temptation with pictures of children is to concentrate solely on their faces, but this default actually narrows our array of storytelling tools. Yes, the eyes are the window to the soul and so forth….but a child is eloquent with everything in his physical makeup. His face is certainly the big, obvious, electric glowing billboard of his feelings, but he speaks in anything he touches, anywhere he runs toward, even the shadows he casts upon the wall. Making pictures of these fragments can produce telling statements about the state of being a child, highlighting the most poignant, and, for us, the most forgotten bits.

Children are all about unrealized potential. Since nothing’s happened yet, everything is possible. Potential and possibility are twin mysteries, and are the common language of kids. Tapping into either one can provide the best element in all of photography, and that is the element of surprise.

SUBMERGED IN BEING

Cropped and enhanced from a group shot. I could sit this young woman in a studio for a thousand years and not get this expression.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

CANDID PORTRAITURE IS VOLATILE, THE DEAD OPPOSITE OF A FORMAL SITTING, and therefore a little scarier for some photographers. We tell ourselves that we gain more control over the results of a staged portrait, since we are dictating so many terms within it…the setting, the light, the choice of props, etc. However, can’t all that control also drain the life out of our subjects by injecting self-consciousness ? Why do you think there are so many tutorials written about how to put your subjects at ease, encourage them to be themselves, persuade them to unclench their teeth? Getting someone to sit where we tell them, do what we tell them, and yet “act naturally” involves a skill set that many photographers must learn over time, since they have to act as life-coach, father-confessor, camp counselor, and seducer, all at once. Also helps if you hand out lollipops.

Then again, shooting on the fly with the hope of capturing something essential about a person who is paying you zero attention is also fraught with risk, since you could crank off fifty frames and still go home without that person revealing anything real within the given time-frame. As with most issues photographic, there is no solution that works all of the time. I do find that one particular class of person affords you a slight edge in candid work, and that is performers. Catch a piece of them in the act of playing, singing, dancing, becoming, and you get as close to the heart of their essence that you, as an outsider, are ever going to get. If they are submerged in being, you might be lucky enough to witness something supernatural.

The more people lose themselves in a quest for the perfect sonata, the ultimate tap step, or the big money note, the less they are trying to give you a “version” of themselves, or worse yet, the rendition of themselves that they think plays well for the camera. As for you, candids work like any other kind of street photography. It’s on you to sense the moment as it arrives and grab it. It’s anything but easy, but better, when it works, then sitting someone amidst props and hoping they won’t freeze up on you.

There are two ways to catch magic in a box when it comes to portraits. One is to have a tremendous relationship with the person who is sitting for you, and the other is to be the best spy in the world when plucking an instant from a real life that is playing out in front of you. You have to know which tack to take, and where the best image can be extracted.

FRONT TO BACK

By MICHAEL PERKINS

NOT ALL PORTRAITS INVOLVE FACES.

I’ll let that little bit of blasphemy sink in for a moment. After all, the face is supposed to be the key to a persona’s entire identity, and God knows that many a mediocre shot has been saved by a fascinating expression, right? The eyes are the window to the soul, and so on, and so forth, etc., etc.

But is this “face-centric” bias worthy of photographers, who are always re-writing the terms of visual engagement on every conceivable subject? Is there one single way to make a person register in an image? Obviously I don’t believe that, or else I wouldn’t have started this argument, but, beyond my native contrariness, I just am not content with there being a single, approved way of visualizing anything. I’ve seen too much amazing work done from every conceivable standpoint to admit of any limitation, or need for a “rule”, even when it comes to portraiture.

The face is many things, but it’s not the entire body, and even if you capture a shot in which the subject’s face is absent, he or she can be so very present in the feel of the picture. Arms, shoulders, the sinews, the stance, the way a body stands in a frame…all can bear testimony.

I recently stumbled onto an impromptu performance by a young string quartet, and faced the usual problem of not being able to simultaneously do justice to all four members’ faces, to balance the tension and concentration written on all their features in performance. In such situations, you have to make some kind of call: the picture becomes a dynamic tension between the shown and the hidden, just as the music is a push-and-pull between dominant and passive forces. You must decide what will remain unseen, and, sometimes, that’s a face.

As the music evolved, the two ladies seen above were, in different instants, either in charge of, or at the service of, the energy of the moment. For this picture, I saw more strength, more power in the back of the violinist than in the front of the cellist. It was body language, a kind of structural tug between the pair, and I voted for what I could not show fully. As it turned out, the violinist actually has a lovely face, one possessing a stern, disciplined intensity. On another day, her story would have been told very differently.

On this day, however, I was happy to have her turn her back on me.

And turn my own head around a bit.

THE WORLD IN A FACE

By MICHAEL PERKINS

The mystery isn’t in the technique. It’s in each of us.

THE AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHER HARRY CALLAHAN , author of the above quotation, knew about the subject of mystery, especially as it regarded women. Make that one woman, namely his wife Eleanor, who posed for Callahan’s camera for sixty-three years in every kind of setting from abstracts to nudes and back again, providing him with his most enduring muse.

Lucky man.

I know exactly how he felt. Because I feel the same way about my own wife, Marian.

Interpreting and re-interpreting a single face over time is one of the best ways I can imagine to train your eye to detect small changes, crucial evolutions in both your subject and your own sense of seeing. And Marian has given me that gift during our time together, as her features seem, to me, to be an inexhaustible source of exploration. It’s a face that is equal parts tenderness and iron resolve, a perfect balance between joy and tragedy, a wellspring of sensations. It is a great face, a great woman’s face, and a fascinating workspace.

Working as I always am to make her relax and forget herself when I am framing her up, I have long since abandoned the practice of announcing that I was going to take her photograph. There is never any posing or sitting. I approach her the way I would a stranger on the street. I wait for the moment when her face is in the act of becoming, than sneak off with whatever I can steal. Sometimes it takes a little more stealth than I am comfortable with, but my motives are simple; I don’t want the mechanics of photography to block what is coming from that face.

Phone conversations are my best friends, as they seem to magically suspend her self-consciousness and her awareness of the schmuck with the camera. And every once in a while, in viewing the results, she bestows my favorite compliment:

“That one’s not too bad…”

For praise like that, I’ll follow a face anywhere. Because the mystery isn’t in the technique.

It’s in all of her.

THE LIVING LAB

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE GREATEST GIFT A SMALL CHILD HAS TO GIVE THE WORLD IS THE VAST, UNMINED ORE OF POSSIBILITY residing inside him. Wow, that really sounded pretentious. But think about it. He or she, as yet, has no wealth to offer, no fully developed talent, no seasoned insight, no marketable skills. It is what he or she has the potential to be that tantalizes us, and our cameras. It is what is just about to be available from these fresh, just-out-of-the-oven souls that amazes us, the degree to which they are not yet….us.

As a photographer, I find there is no better education than to be plunged into the living laboratory of cascading emotion that is a cluster of kids, and the more chaotic and unrehearsed the setting, the richer the results. It’s like shooting the wildest of competitive sports, where everything unfolds in an instant, for an instant. You ride a series of waves, all breaking into their final contours with completely different arcs and surges. There is no map, few guarantees, and just one rule: remain an outsider. The closer to invisibility you can get, the truer the final product.

I volunteer with an educational facility which designs many entry-level discovery workshops and playdates involving young families, requiring a lot of documentary photographs. What would be a chore or an extra duty for overworked administrative staff becomes an excuse, for me, to attend living labs of human experience, and I jump at the chance to walk silently around the edges of whatever adventure these kids are embarked on, whether a simple sing-a-long or a class in amateur dance.

Everything feeds me. It’s a learn-on-the-fly crash course in exposure, composition, often jarring variations in light, and the instantaneous nature of children. To be as non-disruptive as possible, I avoid flash and use a fast 35mm prime, which is a good solid portrait lens. It can’t zoom, however, so there is the extra challenge of getting close enough to the action without becoming a part of it, and in rooms where the lighting is iffy I may have to jack up ISO sensitivity pretty close to the edge of noise. Ideally, I don’t want the kids to be attending to me at all. They are there to react honestly to their friends, parents, and teachers, so there can be no posing, no “look over here, sweetie”, no “cheese”. What you lose in the total control of a formal studio you gain in rare glimpses into real, working minds.

The yields are low: while just anything I shoot can serve as a “document” for the facility’s purposes, for my own needs I am lucky to get one frame in a hundred that gives me something that works technically and emotionally. But for faces like these, I will gladly take those odds.

Who wouldn’t?

Follow Michael Perkins on Twitter @MPnormaleye.

FLATTERY WILL GET YOU NOWHERE

My beautiful mother, well past 21 but curator of a remarkable face. Window light softens, but does not erase, the textures of her features. 1/60 sec., f/4.5, ISO 200. 18mm.

By MICHAEL PERKINS

THE DEPICTION OF THE FACES OF THOSE WE LOVE IS AMONG THE MOST DIVISIVE QUESTIONS IN PHOTOGRAPHY. Since the beginning of the medium, thoughts on how to capture them “best” clearly fall into two opposing camps. In one corner, the feeling that we must idealize, glamorize, venerate the features of those most special in our lives. In the other corner, the belief that we should capture faces as effects of time and space, that is, record them, without seeking to impose standards of grace or beauty on what is in front of the lens. This leads us to see faces as objects among other objects.

The first, more cosmetic view of faces, which calls for ideal lighting, a flattering composition, a little “sweetening” in the taking, will always be the more popular view, and its resultant images will always be cherished for emotionally legitimate reasons. The second view is, let’s “face” it, a hard sell. You have to be ready for a set series of responses from your subjects, usually including:

Don’t take me. I just got up.

God, I look so old. Delete that.

I hate having my picture taken.

That doesn’t even look like me.

Of course, since no one is truly aware of what they “look like”, there is always an element of terror in having a “no frills” portrait taken. God help me, maybe I really do look like that. And most of us don’t want to push to get through people’s defenses. It’s uncomfortable. It’s awkward. And, in this photo-saturated world, it’s a major trick to get people to drop their instinctive masks, even if they want to.

Still.

As I visually measure the advance of age on my living parents (both 80+ ) and have enough etchings on my own features to mirror theirs, I am keener than ever to avoid limiting my images of us all to mere prettiness. I am particularly inspired by photographers who actually entered into a kind of understanding with their closest life partners to make a sort of document out of time’s effects. Two extreme examples: Richard Avedon’s father and Annie Leibovitz’ partner Susan Sontag were both documented in their losing battles with age and disease as willing participants in a very special relationship with very special photographers….arrangements which certainly are out of the question for many of us. And yet, there is so much to be gained by making a testament of sorts out of even simple snaps. This was an important face in my life, the image can say, and here is how it looked, having survived more than 3/4 of a century. Such portraits are not to be considered “right” or “wrong” against more conventional pictures, but they should be at least a part of the way we mark human lives.

Everyone has to decide their own comfort zone, and how far it can be extended. But I think we have to stretch a bit. Pictures of essentially beautiful people who, at the moment the shutter snaps, haven’t done up their hair, put on their makeup, or conveniently lost forty pounds. People in less than perfect light, but with features which have eloquent statements and truths writ large in their every line and crevice. We should also practice on ourselves, since our faces are important to other people, and ours, like theirs, are going to go away someday.

In trying to record these statements and truths, mere flattery will get us nowhere. The camera has an eye to see; let’s take off the rose-colored filter, at least for a few frames.

Related articles

- The Great Richard Avedon (sandroesposito.wordpress.com)